Bacterial infections remain one of the main complications in cirrhosis and worsen patients’ prognosis and quality of life. An increase in multidrug resistant microorganism (MDRM) infections among patients with cirrhosis, together with infection-related mortality rates, have been reported in recent years. Therefore, adaptation of the initial empiric antibiotic approach to different factors, particularly the local epidemiology of MDRM infections, has been recommended. We aim to describe the main features, outcomes and risk factors of MDRM infections in patients with cirrhosis.

MethodsProspective registry of all episodes of in-hospital infections occurring among cirrhotic patients admitted within a 2-year period at a single center. Clinical and microbiological data were collected at the time of infection diagnosis, and the in-hospital mortality rate of the infectious episode was registered.

ResultsA total of 139 infectious episodes were included. The disease-causing microorganism was identified in 90 episodes (65%), of which 31 (22%) were caused by MDRM. The only two factors independently associated with MDRM infections were rectal colonization by MDRM and a nosocomial or healthcare-associated source. The infection-related mortality rate was 18.7%. MDRM infection and a past history of hepatic encephalopathy were independently associated with in-hospital mortality.

ConclusionsAlmost one fourth of bacterial infections occurring in admitted cirrhotic patients were due to MDRM. Rectal colonization was the most important risk factor for MDRM infections in decompensated cirrhosis. Screening for MDRM rectal colonization in patients admitted for decompensated cirrhosis should be assessed as a tool to improve local empiric antibiotic strategies.

Las infecciones bacterianas representan una de las principales complicaciones del paciente cirrótico, empeoran su pronóstico y calidad de vida. Recientemente se ha descrito un aumento de infecciones por microorganismos multiresistentes (MMR) en pacientes cirróticos, con un incremento de la mortalidad relacionada con la infección. Se recomienda adecuar el tratamiento antibiótico empírico inicial a diferentes factores, en particular a la epidemiología local. El objetivo del estudio es describir las principales características clínicas, evolución y factores de riesgo asociados a infecciones por MMR en cirrosis.

MétodosSe registraron todos los episodios de infecciones bacterianas que presentaron los pacientes hospitalizados durante un período de 2 años en un único centro. Se recogieron datos clínicos y microbiológicos en el momento de la infección y la tasa de mortalidad intrahospitalaria.

ResultadosSe incluyó un total de 139 episodios de infección. Se identificó el microorganismo responsable de la infección en 90 episodios (65%), de los cuales en 31 (22%) la causa fue un MMR. Los 2 factores asociados independientemente con las infecciones MMR fueron colonización rectal por MMR y origen nosocomial o asociado al sistema sanitario de la infección. La mortalidad intrahospitalaria relacionada con la infección fue del 18,7%. La infección por MMR y tener antecedentes de encefalopatía hepática se asociaron independientemente con la mortalidad intrahospitalaria.

ConclusionesCasi una cuarta parte de las infecciones que aparecen en los pacientes cirróticos hospitalizados son producidas por MMR. La colonización rectal fue el factor de riesgo más importante para infecciones por MMR. El cribado de colonización rectal por MMR en pacientes con cirrosis descompensada debe valorarse como una herramienta para mejorar las estrategias de terapia antibiótica empírica.

Bacterial infections are a frequent complication in cirrhotic patients and are associated with worse outcomes.1 In addition, population-based studies have shown that cirrhosis is a predisposing factor for the development of nosocomial infections.1,2 Although only 25–35% of the infections among patients with cirrhosis occur during their hospital stay, this incidence is five times higher than in patients admitted without cirrhosis.1 Bacterial infection increases the mortality rate in decompensated patients with cirrhosis up to four times, reaching 30% at one month and 63% at one year.2

In recent years, the growing use of invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, the widespread implementation of antibiotic prophylaxis and the increasing use of broad-spectrum antibiotics have led to a change in the epidemiology of infections in cirrhotic patients. In fact, an increase in the number of infections caused by multidrug resistant microorganisms (MDRM) and fungi1–8 has been reported. It has also been observed that MDRM infections are associated with higher infection-related mortality in patients with cirrhosis.9 This change in the epidemiology of infections has prompted a shift in the initial empirical antibiotic approach when infections are diagnosed in these patients. Moreover, it has been recommended to take into account several factors (time of acquisition of the infection, severity of infections, individual risk factors for MDRM infections, source and, particularly, the local epidemiology of infections) in this decision-making process.9–12 Particularly, updated knowledge of the local epidemiology of infections has become a key factor for antibiotic treatment selection in these patients.

We aim to characterize bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis admitted to our center and to identify the associated risk factors for MDRM infections in this population.

MethodsAll human studies were conducted in line with Declaration of Helsinki principles and current legislation on the confidentiality of personal data and were approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol (PI-17-219). Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study designThis is an observational, prospective study in which all infectious episodes in adult cirrhotic patients admitted to the University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol Liver Unit (Badalona, Catalonia, Spain) from December 2017 to May 2019 were included. Patients with a history of solid organ transplantation or congenital or acquired immunosuppression were excluded. Diagnosis of cirrhosis was based on liver biopsy or a composite of clinical signs and findings provided by laboratory test results, endoscopy and radiologic imaging. In patients admitted because of cirrhotic decompensation, a routine screening for bacterial infection was performed at admission with blood and urine cultures, chest imaging, and cell count and ascitic fluid culture if ascitic was present. Stool and sputum cultures were performed according to clinical suspicion. This screening was repeated at the discretion of the treating physician during hospital admission.

Infections were defined as follows: urinary tract infection (UTI) was diagnosed as a combination of urinary tract symptoms and an abnormal urine analysis or positive urine culture; pneumonia was defined as the presence of clinical signs of parenchymal lung infection and documented infiltrates on chest imaging (X-ray or CT-scan) or positive respiratory culture (sputum, deep tracheal or bronchial lavage); bacteraemia was defined as having a recognized pathogen cultured from one or more blood cultures. Microorganisms such as diphteroids, Bacillus spp., Propionibacteriurm spp., and coagulase-negative staphylococci were considered common skin contaminants unless they were cultured from two or more blood cultures drawn on separate occasions,13spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) was diagnosed as the presence of >250neutrophils/mm3 in ascitic fluid; other infections included endocarditis (as defined by modified Duke criteria14), cellulitis (as defined by the presence of localized symptoms/sing of infection and/or positive culture) and Clostridioides difficile colitis (as defined by a positive toxin in stool samples, together with acute diarrhea).

When the infection occurred later than 48h after hospital admission, it was considered to be nosocomial. Infections were considered to be healthcare-associated (HCA) if the patient had been admitted to hospital within the previous three months, had been on a haemodialysis program or had been institutionalized. The remaining infections were considered to be community-acquired. When more than one infectious episode occurred in the same patient during their hospital stay, each one was considered to be an independent event.

A causative microorganism was considered to be MDRM if resistance to at least three antibiotic families including beta-lactams was demonstrated.15

Infection treatment was performed following EASL guideline recommendations16 or clinician criteria. Since EASL guidelines recommended the same first empirical treatment for both nosocomial or HCA infections, we decided to perform two statistical analyses (combining nosocomial and HCA origin of infections or not).

Infection resolution was defined as the disappearance of all clinical signs of infection once antibiotic treatment was completed.

Data collectionA specific database was created in order to collect epidemiological characteristics (age, gender, toxic habits), severe comorbidities (diabetes, chronic renal disease, malignancies) and cirrhosis characteristics (etiology, date of diagnosis, previous decompensations, previous acute kidney injury (AKI) episodes according to EASL criteria,16,17 the presence of oesophageal varices), treatment with norfloxacin and rifaximin within four weeks before admission, antibiotic therapy within the previous three months, as well as the clinical features of the infectious episode (reason for hospital admission, concomitant acute alcoholic hepatitis, degree of hepatic failure according to the MELD and Child–Pugh classifications, acute-on-chronic liver failure criteria18). Biological parameters at the time of infection diagnosis (leukocyte count, C-reactive protein – CRP–, albumin, bilirubin, prothrombin time, creatinine, sodium) were also registered. When more than one complication of decompensation of cirrhosis was present at admission, the criteria used to define the hierarchic causality of admission was: portal hypertensive bleeding, infection and hepatic encephalopathy and ascites. Regarding the infectious episode, the source and type of infection and its microbiological features (causative microorganism, antibiotic treatment, the need to modify antibiotic treatment to increase antibiotic spectrum, infection outcomes and mortality related to infection) were registered. Rectal swab for MDRM was performed in all infectious episodes at the time of diagnosis. In those patients with more than one infectious episode, rectal swab for MDRM was repeated only in case the first rectal swab was negative.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are expressed as absolute values and frequencies, continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation. The Student's t test was used for the comparison of continuous variables with a parametric distribution, Mann–Whitney's U test was used for non-parametric distribution variables, and the Chi-square test was used for qualitative variables. In all analyses, the significance level was set at a p value <0.05. A Binary logistic regression test was used to assess the risk factors of MDMR infection and factors associated with infections-related mortality. All statistical analyses were carried out with the SPSS version 23 statistical package.

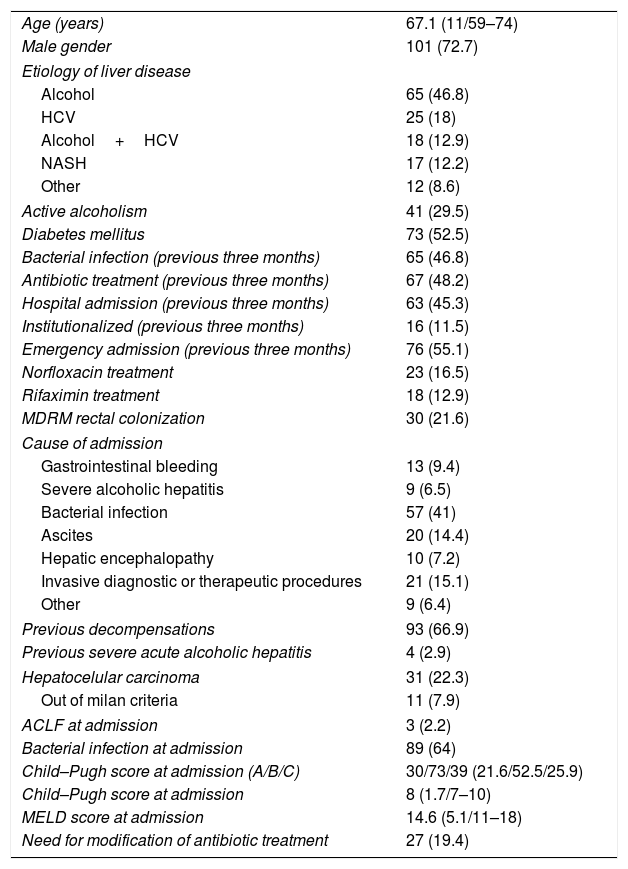

ResultsDuring the study period, a total of 340 admissions corresponding to 195 patients with cirrhosis were identified. Among them, at least one infectious episode was documented in 87 admissions (26%), a single infectious episode was documented in 61 admissions (18%), while two or more infectious episodes were documented in 26 admissions (8%). As a result, a total of 139 infectious episodes were included in the study, 64% of which were already present at the time of hospital admission although most of these episodes [69%] were of nosocomial or HCA origin. The main characteristics of the patients at the time every infectious episode was diagnosed are summarized in Table 1.

Main characteristics of the patients at each infectious episode (N=139).

| Age (years) | 67.1 (11/59–74) |

| Male gender | 101 (72.7) |

| Etiology of liver disease | |

| Alcohol | 65 (46.8) |

| HCV | 25 (18) |

| Alcohol+HCV | 18 (12.9) |

| NASH | 17 (12.2) |

| Other | 12 (8.6) |

| Active alcoholism | 41 (29.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 73 (52.5) |

| Bacterial infection (previous three months) | 65 (46.8) |

| Antibiotic treatment (previous three months) | 67 (48.2) |

| Hospital admission (previous three months) | 63 (45.3) |

| Institutionalized (previous three months) | 16 (11.5) |

| Emergency admission (previous three months) | 76 (55.1) |

| Norfloxacin treatment | 23 (16.5) |

| Rifaximin treatment | 18 (12.9) |

| MDRM rectal colonization | 30 (21.6) |

| Cause of admission | |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 13 (9.4) |

| Severe alcoholic hepatitis | 9 (6.5) |

| Bacterial infection | 57 (41) |

| Ascites | 20 (14.4) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 10 (7.2) |

| Invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures | 21 (15.1) |

| Other | 9 (6.4) |

| Previous decompensations | 93 (66.9) |

| Previous severe acute alcoholic hepatitis | 4 (2.9) |

| Hepatocelular carcinoma | 31 (22.3) |

| Out of milan criteria | 11 (7.9) |

| ACLF at admission | 3 (2.2) |

| Bacterial infection at admission | 89 (64) |

| Child–Pugh score at admission (A/B/C) | 30/73/39 (21.6/52.5/25.9) |

| Child–Pugh score at admission | 8 (1.7/7–10) |

| MELD score at admission | 14.6 (5.1/11–18) |

| Need for modification of antibiotic treatment | 27 (19.4) |

HCV, hepatitis C virus; NASH, no alcoholic steatohepatitis; MDRM, multi drug resistant microorganism; ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure.

Results are expressed as n(%); mean (SD/percentile 25–75).

UTI, respiratory infections and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis were the most common types of infection, accounting for 73% of the infectious episodes (Fig. 1). The causative microorganism was identified in 90 infectious episodes (65%).

Epidemiological, clinical and microbiological characteristics of MDRM infectionsIn all, 31 infections caused by MDRM were identified, corresponding to 22% of all the infectious episodes and 34% of those infections with a known causative microorganism. The most frequently isolated MDRMs were extended-spectrum beta-lactamase Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli (11 and six cases, respectively), quinolone-resistant Enterococcus faecium (eight cases) and carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (six cases). UTI was the most common type of infection (61.2% of all MDRM infections). In patients with MDRM rectal colonization, the rectal colonizing microorganism was responsible for the infectious episode in 76.5% the cases. Almost half of the MDRM infections (48%), were empirically treated with a broad-spectrum antibiotic, as compared to 27% in non-MDRM infections.

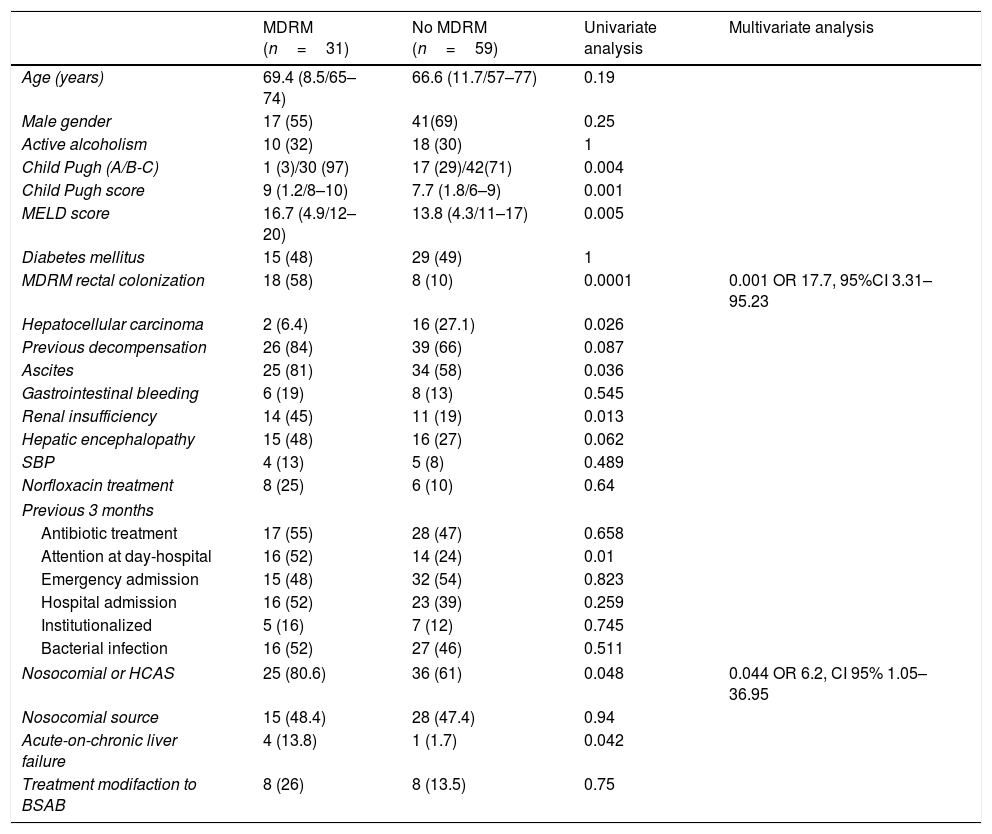

Table 2 summarizes the main features of those infectious episodes in which the causative microorganism was identified and compares MDRM with non-MDRM infections. MDRM infections tended to occur more often among patients with more advanced liver failure as reflected by higher Child–Pugh and MELD scores and a trend toward a higher proportion of previous decompensations of cirrhosis. In 57% of the MDRM infections, at least two of the previously described risk factors for MDRM (previous treatment with norfloxacin, history of bacterial infection in the previous three months, systemic antibiotic treatment in the previous three months, nosocomial source of the infection and rectal colonization for MDRM)9,19–22 were identified. In contrast, this only occurred in 19% of non-MDMR infections (p<0.001). Among the known risk factors for MDRM infections, exposure to norfloxacin within the previous three months was not associated with MDRM infections in our cohort. Child Pugh and MELD scores, rectal colonization by MDRM, a history of hepatocellular carcinoma, ascites or AKI episode, day-care hospital admission within the previous three months, nosocomial or HCA infection source and presence of ACLF were associated with MDRM in the univariate analysis, but only rectal colonization by MDRM (OR 17.7, 95%CI 3.31–95.23; p=0.001) and nosocomial or HCA source (OR 6.2, 95%CI 1.05–36.95; p=0.044) were independently associated with MDRM infection.

Risk factors of MDRM.

| MDRM (n=31) | No MDRM (n=59) | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.4 (8.5/65–74) | 66.6 (11.7/57–77) | 0.19 | |

| Male gender | 17 (55) | 41(69) | 0.25 | |

| Active alcoholism | 10 (32) | 18 (30) | 1 | |

| Child Pugh (A/B-C) | 1 (3)/30 (97) | 17 (29)/42(71) | 0.004 | |

| Child Pugh score | 9 (1.2/8–10) | 7.7 (1.8/6–9) | 0.001 | |

| MELD score | 16.7 (4.9/12–20) | 13.8 (4.3/11–17) | 0.005 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15 (48) | 29 (49) | 1 | |

| MDRM rectal colonization | 18 (58) | 8 (10) | 0.0001 | 0.001 OR 17.7, 95%CI 3.31–95.23 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 2 (6.4) | 16 (27.1) | 0.026 | |

| Previous decompensation | 26 (84) | 39 (66) | 0.087 | |

| Ascites | 25 (81) | 34 (58) | 0.036 | |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 6 (19) | 8 (13) | 0.545 | |

| Renal insufficiency | 14 (45) | 11 (19) | 0.013 | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 15 (48) | 16 (27) | 0.062 | |

| SBP | 4 (13) | 5 (8) | 0.489 | |

| Norfloxacin treatment | 8 (25) | 6 (10) | 0.64 | |

| Previous 3 months | ||||

| Antibiotic treatment | 17 (55) | 28 (47) | 0.658 | |

| Attention at day-hospital | 16 (52) | 14 (24) | 0.01 | |

| Emergency admission | 15 (48) | 32 (54) | 0.823 | |

| Hospital admission | 16 (52) | 23 (39) | 0.259 | |

| Institutionalized | 5 (16) | 7 (12) | 0.745 | |

| Bacterial infection | 16 (52) | 27 (46) | 0.511 | |

| Nosocomial or HCAS | 25 (80.6) | 36 (61) | 0.048 | 0.044 OR 6.2, CI 95% 1.05–36.95 |

| Nosocomial source | 15 (48.4) | 28 (47.4) | 0.94 | |

| Acute-on-chronic liver failure | 4 (13.8) | 1 (1.7) | 0.042 | |

| Treatment modifaction to BSAB | 8 (26) | 8 (13.5) | 0.75 | |

MDRM: multi-drug-resistant microorganism; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; HCAS: health-care associated source; BSAB: broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Results expressed as n (%); mean (SD/percentile 25–75).

We also analyzed the risk factors associated with rectal colonization by MDRM. In the univariate analysis, a higher Child–Pugh score, previous treatment with norfloxacin and previous treatment with rifaximin were significantly associated with rectal colonization. However, in the multivariate analysis, only previous treatment with norfloxacin (OR 4.19, 95%CI 1.55–11.35; p=0.005) was independently associated with rectal colonization by MDRM.

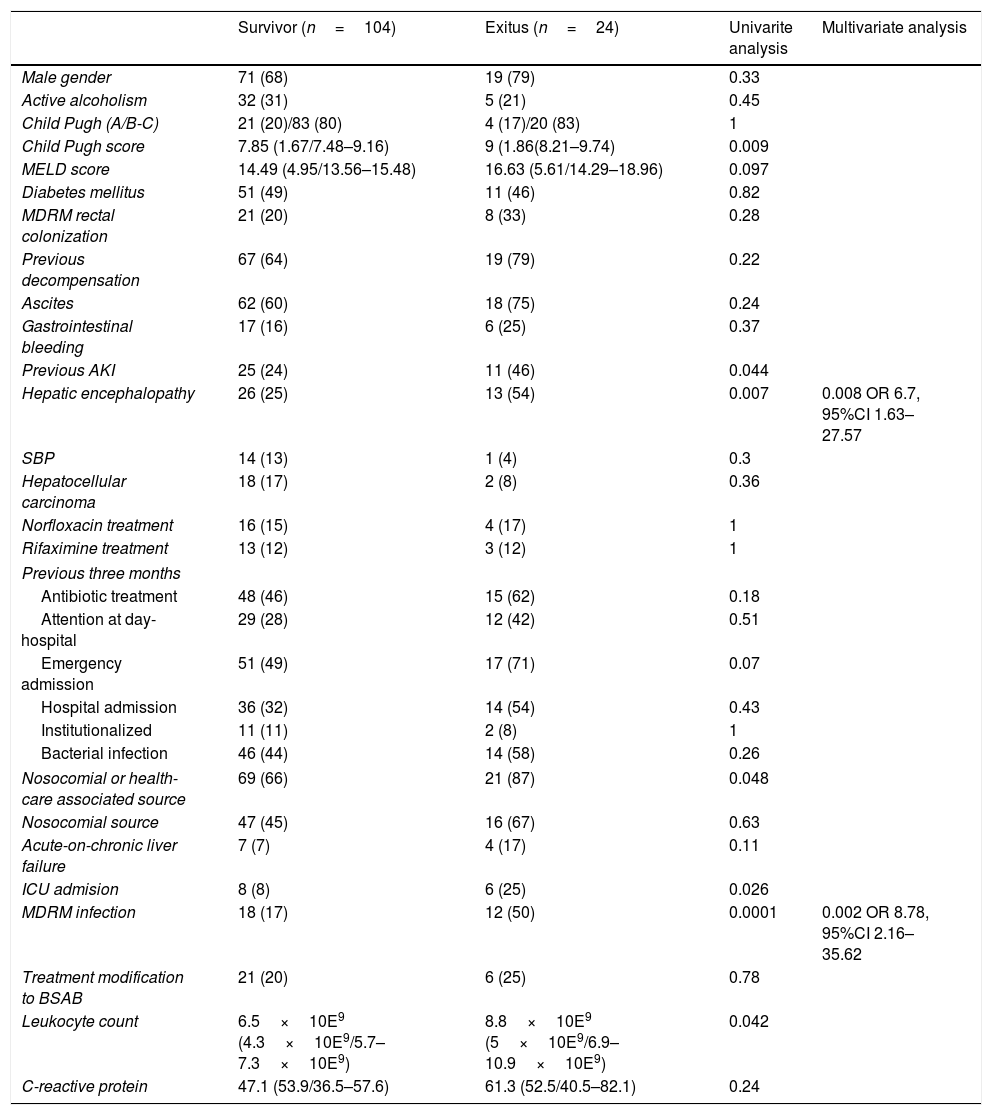

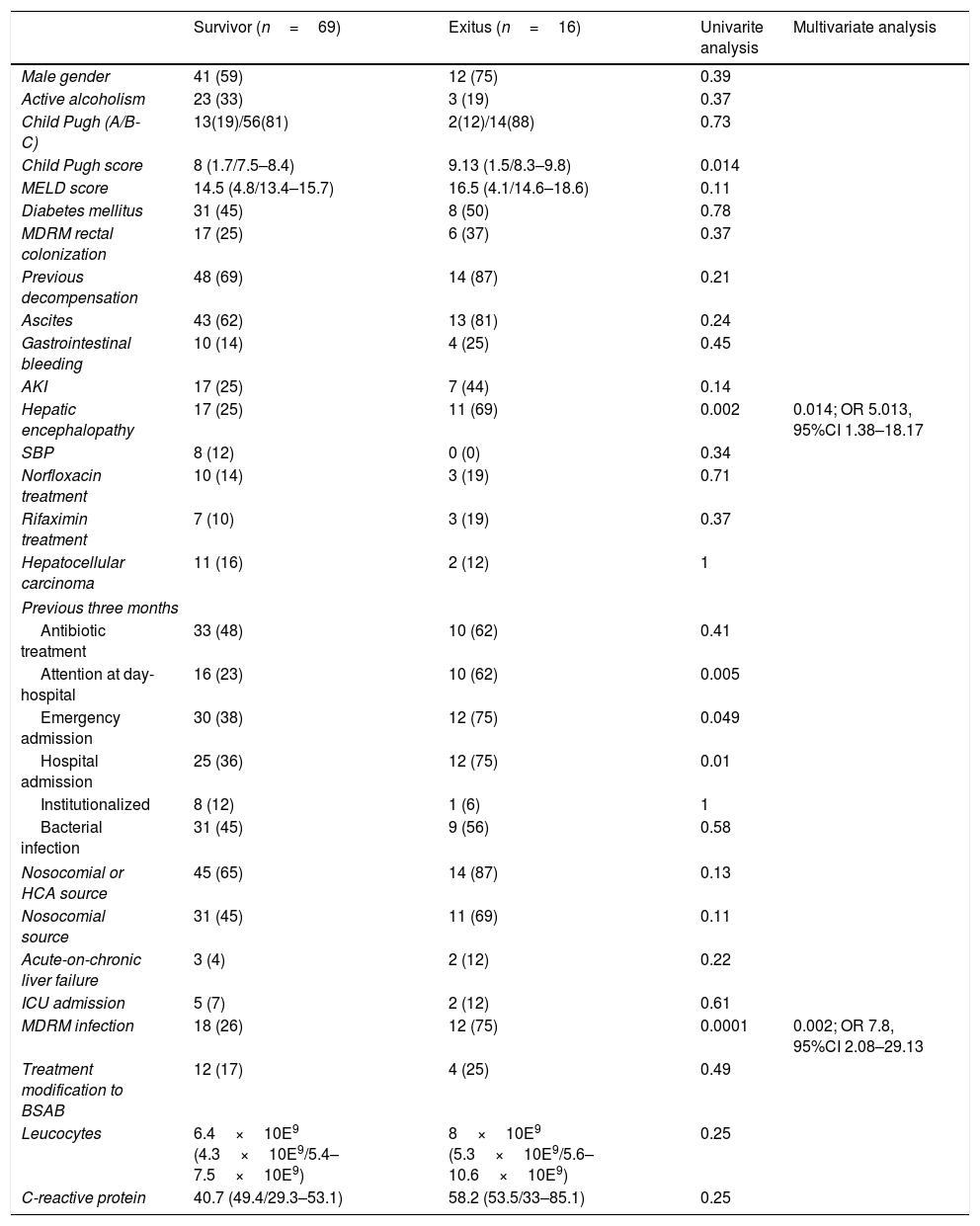

Risk factors for infection-related mortalityTo avoid confusion relating to hepatocellular carcinoma, we excluded all patients with hepatocellular carcinoma outside of Milan criteria. Finally, twenty-four out of the total of 128 infectious episodes resulted in death (19%). In the univariate analysis, a higher Child–Pugh score, a past episode of AKI or hepatic encephalopathy, admission during the previous three months, MDRM infection, a nosocomial or HCA source, ICU admission, a higher blood leukocyte count and a lower level of albumin were associated with in-hospital mortality, but only a past history of hepatic encephalopathy (OR 6.7, 95%CI 1.63–27.57; p=0.008) and MDRM infection (OR 8.78, 95%CI 2.16–35.62; p=0.002) were independently associated with in-hospital mortality (Table 3). In order to include microbiological factors, we performed a secondary analysis in those infectious episodes in which the causative bacteria were identified (Table 4). In the univariate analysis, the Child Pugh score, a past history of hepatic encephalopathy, MDRM infection at hospital admission, emergency admission or day-care hospital admission within the previous three months were significantly associated with in-hospital mortality. However, the only factors independently associated with in-hospital mortality were a past history of hepatic encephalopathy (OR 5.013, 95%CI 1.38–18.17, p=0.014) or MDRM infections (OR 7.8, 95%CI 2.08–29.13, p=0.002).

Risk factors for in-hospital infection-related mortality. Hepatocellular carcinoma with Milan-out criteria exclused (N=128).

| Survivor (n=104) | Exitus (n=24) | Univarite analysis | Multivariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 71 (68) | 19 (79) | 0.33 | |

| Active alcoholism | 32 (31) | 5 (21) | 0.45 | |

| Child Pugh (A/B-C) | 21 (20)/83 (80) | 4 (17)/20 (83) | 1 | |

| Child Pugh score | 7.85 (1.67/7.48–9.16) | 9 (1.86(8.21–9.74) | 0.009 | |

| MELD score | 14.49 (4.95/13.56–15.48) | 16.63 (5.61/14.29–18.96) | 0.097 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 51 (49) | 11 (46) | 0.82 | |

| MDRM rectal colonization | 21 (20) | 8 (33) | 0.28 | |

| Previous decompensation | 67 (64) | 19 (79) | 0.22 | |

| Ascites | 62 (60) | 18 (75) | 0.24 | |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 17 (16) | 6 (25) | 0.37 | |

| Previous AKI | 25 (24) | 11 (46) | 0.044 | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 26 (25) | 13 (54) | 0.007 | 0.008 OR 6.7, 95%CI 1.63–27.57 |

| SBP | 14 (13) | 1 (4) | 0.3 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 18 (17) | 2 (8) | 0.36 | |

| Norfloxacin treatment | 16 (15) | 4 (17) | 1 | |

| Rifaximine treatment | 13 (12) | 3 (12) | 1 | |

| Previous three months | ||||

| Antibiotic treatment | 48 (46) | 15 (62) | 0.18 | |

| Attention at day-hospital | 29 (28) | 12 (42) | 0.51 | |

| Emergency admission | 51 (49) | 17 (71) | 0.07 | |

| Hospital admission | 36 (32) | 14 (54) | 0.43 | |

| Institutionalized | 11 (11) | 2 (8) | 1 | |

| Bacterial infection | 46 (44) | 14 (58) | 0.26 | |

| Nosocomial or health-care associated source | 69 (66) | 21 (87) | 0.048 | |

| Nosocomial source | 47 (45) | 16 (67) | 0.63 | |

| Acute-on-chronic liver failure | 7 (7) | 4 (17) | 0.11 | |

| ICU admision | 8 (8) | 6 (25) | 0.026 | |

| MDRM infection | 18 (17) | 12 (50) | 0.0001 | 0.002 OR 8.78, 95%CI 2.16–35.62 |

| Treatment modification to BSAB | 21 (20) | 6 (25) | 0.78 | |

| Leukocyte count | 6.5×10E9 (4.3×10E9/5.7–7.3×10E9) | 8.8×10E9 (5×10E9/6.9–10.9×10E9) | 0.042 | |

| C-reactive protein | 47.1 (53.9/36.5–57.6) | 61.3 (52.5/40.5–82.1) | 0.24 | |

ICU: intensive care unit; MDRM: multi-drug-resistant microorganism; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; AKI: acute kidney injury; BSAB: broad spectrum antibiotic.

Risk factors for in-hospital infection-related mortality in infectious episodes in which the causative bacteria were identified and Hepatocellular carcinoma out of Milan criteria were excluded (N=85).

| Survivor (n=69) | Exitus (n=16) | Univarite analysis | Multivariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 41 (59) | 12 (75) | 0.39 | |

| Active alcoholism | 23 (33) | 3 (19) | 0.37 | |

| Child Pugh (A/B-C) | 13(19)/56(81) | 2(12)/14(88) | 0.73 | |

| Child Pugh score | 8 (1.7/7.5–8.4) | 9.13 (1.5/8.3–9.8) | 0.014 | |

| MELD score | 14.5 (4.8/13.4–15.7) | 16.5 (4.1/14.6–18.6) | 0.11 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 31 (45) | 8 (50) | 0.78 | |

| MDRM rectal colonization | 17 (25) | 6 (37) | 0.37 | |

| Previous decompensation | 48 (69) | 14 (87) | 0.21 | |

| Ascites | 43 (62) | 13 (81) | 0.24 | |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 10 (14) | 4 (25) | 0.45 | |

| AKI | 17 (25) | 7 (44) | 0.14 | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 17 (25) | 11 (69) | 0.002 | 0.014; OR 5.013, 95%CI 1.38–18.17 |

| SBP | 8 (12) | 0 (0) | 0.34 | |

| Norfloxacin treatment | 10 (14) | 3 (19) | 0.71 | |

| Rifaximin treatment | 7 (10) | 3 (19) | 0.37 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 11 (16) | 2 (12) | 1 | |

| Previous three months | ||||

| Antibiotic treatment | 33 (48) | 10 (62) | 0.41 | |

| Attention at day-hospital | 16 (23) | 10 (62) | 0.005 | |

| Emergency admission | 30 (38) | 12 (75) | 0.049 | |

| Hospital admission | 25 (36) | 12 (75) | 0.01 | |

| Institutionalized | 8 (12) | 1 (6) | 1 | |

| Bacterial infection | 31 (45) | 9 (56) | 0.58 | |

| Nosocomial or HCA source | 45 (65) | 14 (87) | 0.13 | |

| Nosocomial source | 31 (45) | 11 (69) | 0.11 | |

| Acute-on-chronic liver failure | 3 (4) | 2 (12) | 0.22 | |

| ICU admission | 5 (7) | 2 (12) | 0.61 | |

| MDRM infection | 18 (26) | 12 (75) | 0.0001 | 0.002; OR 7.8, 95%CI 2.08–29.13 |

| Treatment modification to BSAB | 12 (17) | 4 (25) | 0.49 | |

| Leucocytes | 6.4×10E9 (4.3×10E9/5.4–7.5×10E9) | 8×10E9 (5.3×10E9/5.6–10.6×10E9) | 0.25 | |

| C-reactive protein | 40.7 (49.4/29.3–53.1) | 58.2 (53.5/33–85.1) | 0.25 | |

AKI: acute kidney injury; MDRM: multi-drug-resistant microorganism; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; HCA: hospital care associated; BSAB: broad-spectrum antibiotic.

This was a prospective study aiming to describe the spectrum of bacterial infections in patients admitted for decompensated cirrhosis. In agreement with previous studies,1,9 we found a prevalence of 26% of bacterial infections in this population, most of which were of nosocomial or HCA origin (69%). Moreover, infection was the most frequent reason for hospital admission (41%) in our cohort.

The importance of bacterial infection in cirrhosis is based on it being one of the most important causes of liver disease progression and the worsening of disease prognosis, especially in the case of MDRM infections.2 Our study confirms the increasing prevalence of MDRM infections in patients with cirrhosis, accounting for up to one fifth of those infections with an identified causative microorganism. Although our figures are close to those reported in a recent, large, multicentre study, the prevalence of MDRM infections may vary widely between different geographic areas.19 Therefore, the different guidelines recommend adapting the therapeutic approach taking into account local epidemiology. Accordingly, the aim of the present study was to describe the clinical-microbiological characteristics of the bacterial infections occurring in patients with cirrhosis admitted to a Hepatology Unit of an academic hospital which does not have a hepatic-transplant program.

We found that only the nosocomial or HCA source of infections and rectal colonization by MDRM were independently associated with the MDRM etiology of infections. Since the nosocomial source of infection had already been identified as an MDRM infection risk factor in several studies,21 we decided to evaluate the nosocomial source separately from the HCA source. However, in our analysis, neither nosocomial nor HCA sources were associated with MDRM infection when analyzed separately, probably due to the limited number of cases in our cohort. Importantly, the increasing use of outpatient healthcare resources (including invasive procedures such as esophageal band ligation or liver biopsy) has changed the profile of HCA user with advanced liver disease. Therefore, we suggest that the HCA source should also be considered as part of the nosocomial infection criteria.

Another interesting finding in our study is that prophylaxis with norfloxacin was associated with an increased risk of rectal colonization by MDRM. However, although we observed a non-significant trend toward an increased risk of MDRM infection in the group of patients on norfloxacin, in agreement with some recent studies,19,22 although this is in contrast to what has previously been reported.23

Regarding mortality, we observed that MDRM infections were associated with a higher in-hospital infection-related mortality rate, in line with previous reports.9 Moreover, a past history of hepatic encephalopathy as a surrogate marker of advanced liver disease was also independently associated with mortality. The impact of MDRM etiology on infection-related mortality highlights the need for optimized empirical antibiotic policies or prediction tools for MDRM infections.

Interestingly, as previously reported,21 we found that rectal colonization by MDRM favors infectious episodes by the same MDRM. These results highlight the need for studies providing data on MDRM rectal colonization in decompensated cirrhotic patients. Moreover, a standardized strategy for MDRM rectal colonization screening and information regarding the optimal target population (i.e., all cirrhotic patients, only critically ill patients, patients meeting nosocomial criteria or with recent healthcare resources use or those with more advanced liver disease) or the optimal time or interval for this screening (only at the time of admittance, weekly or every other week) are still lacking. Likewise, a strict surveillance of MDRM carriers (which decreases the risk of transmission between hospitalized patients21) should also be carried out.

In spite of its strengths, such as its prospective design and it being a single-center study, we are aware of several limitations of our study. Firstly, its limited simple size, with a small number of MDRM infectious episodes, precluded achieving more robust results, particularly regarding the risk factors for MDRM infections and mortality-related factors. Secondly, the fact that rectal colonization screening was carried out at a single moment and only at the time of infection diagnosis did not allow us to elucidate the contribution of this fact to the development of MDRM infection.

In conclusion, health care resources use seems to be an important determinant for being an MDRM carrier, and this is the most important risk factor for MDRM infections in decompensated cirrhosis. Our data suggest that the implementation of screening policies for MDRM colonization might be of benefit for the prediction and early detection of MDRM infections in decompensated cirrhosis.

Ethical considerationsAll human studies were conducted in line with Declaration of Helsinki principles and current legislation on the confidentiality of personal data and were approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol (PI-17-219).

Funding sourcesNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.