Heat stroke due to overexertion is an uncommon but severe illness characterised by hyperthermia exceeding 40 °C and central nervous system dysfunction secondary to intense exercise in a hot or humid environment.1–3 Liver damage is common and usually mild and transient. Acute liver failure is an uncommon complication with a poor prognosis.2–4 Conservative treatment appears to suffice in most cases,3 though liver transplantation (LT) may be necessary in some cases.2,3

We report the case of a 21-year-old man with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus who, while hiking at midday in August, started to experience cramping in his legs, dysarthria, a body temperature of 42 °C and an initial Glasgow score of 3/15. Treatment was started with external measures to decrease the man's body temperature (hypothermic blankets), intravenous cold serum, naloxone, flumazenil and infusion of N-acetylcysteine (300 mg/kg in 21 h), without recovery of his level of consciousness, and a need for orotracheal intubation. Laboratory testing at 24 h revealed rhabdomyolysis, acute kidney failure (creatinine 3.1 mg/dl) with intact diuresis, serious hepatitis with AST/ALT 6474/8057 UI/l, total bilirubin 3.87 mg/dl, normal amoniaemia, disseminated intravascular coagulation with INR 3, Quick index 16%, lactate 3.1 mmol/l, platelets 20,000/μl and myocardial damage with troponin T 5000 ng/l (echocardiogram with diffuse hypokinesia and left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] 50%). A brain CT scan and liver ultrasound were performed and showed no abnormalities. The patient was transferred in haemodynamically stable condition from the ICU to a tertiary hospital 48 h from the onset for assessment for LT.

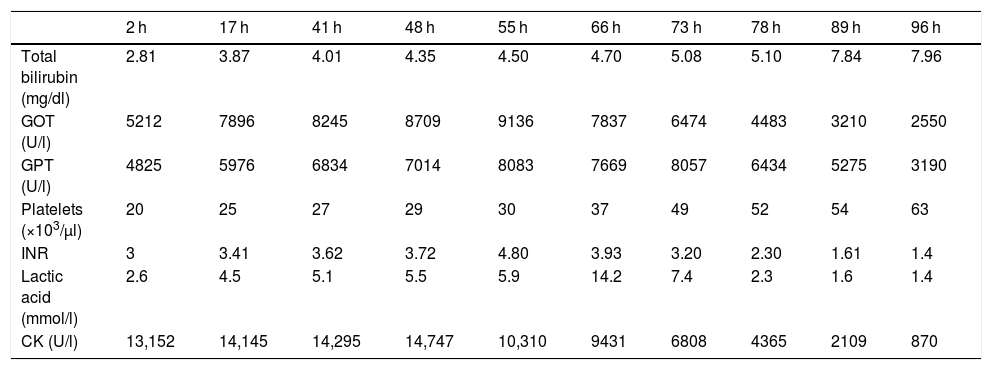

A pre-LT assessment was started (negative HAV/HBV/HCV/HEV/HIV/CMV/EBV/parvovirus and Treponema pallidum) and the patient was included in code 0 with a diagnosis of fulminant hepatitis secondary to heat stroke (MELD 41). After 8 h had elapsed since his ICU admission, he started to show haemodynamic instability, oliguria (120 mL in 12 h), worsening of kidney function (creatinine 3.7 mg/dl) requiring norepinephrine at maximum doses (2 μg/kg/min), terlipressin (4 mg in 100 mL of 0.9% normal saline in 24 h), continuous arteriovenous and intravenous haemodiafiltration (HDF), glucocorticoids (hydrocortisone 100 mg IV every 6 h) and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (IV meropenem 2 g/8 h and IV linezolid 600 mg/12 h). When 18 h had passed since these measures were started, the patient was refractory to treatment; with his blood pressure 50/30 mmHg and his lactic acid 14 mmol/l, a short-term fatal prognosis was made. However, gradually, without any treatment changes, he showed haemodynamic improvement, his lactic acid dropped (3 mmol/l) and haemodialysis and vasoactive support could be stopped 48 h after his ICU admission. Given the patient's clinical and laboratory improvement (Table 1), a decision was made to remove him from the LT list. Five days after his ICU stay, he was discharged from the hospital ward.

Changes over time in laboratory values.

| 2 h | 17 h | 41 h | 48 h | 55 h | 66 h | 73 h | 78 h | 89 h | 96 h | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 2.81 | 3.87 | 4.01 | 4.35 | 4.50 | 4.70 | 5.08 | 5.10 | 7.84 | 7.96 |

| GOT (U/l) | 5212 | 7896 | 8245 | 8709 | 9136 | 7837 | 6474 | 4483 | 3210 | 2550 |

| GPT (U/l) | 4825 | 5976 | 6834 | 7014 | 8083 | 7669 | 8057 | 6434 | 5275 | 3190 |

| Platelets (×103/μl) | 20 | 25 | 27 | 29 | 30 | 37 | 49 | 52 | 54 | 63 |

| INR | 3 | 3.41 | 3.62 | 3.72 | 4.80 | 3.93 | 3.20 | 2.30 | 1.61 | 1.4 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/l) | 2.6 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 5.9 | 14.2 | 7.4 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| CK (U/l) | 13,152 | 14,145 | 14,295 | 14,747 | 10,310 | 9431 | 6808 | 4365 | 2109 | 870 |

h: hours since onset of episode; INR: international normalised ratio.

During his stay on the ward, he followed a satisfactory course, remaining haemodynamically stable with intact kidney function and diuresis, and a Glasgow score of 15/15. He was discharged 8 days from the start of the episode with improved laboratory results (total bilirubin 5.95 mg/dl, aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase [AST/ALT] 124/393 U/l, creatine kinase [CK] 140 U/l, platelets 268,000, international normalised ratio [INR] 1, Quick index 100%) and an echocardiogram with a normal LVEF.

Cases of serious liver failure secondary to heat stroke, with or without multiorgan dysfunction, improve in more than 80% of cases with medical treatment. Improvement in liver function is possible with conservative management;3 LT is an uncommonly indicated treatment. Factors associated with a worse prognosis are a temperature higher than 42 °C, early multiorgan failure with need for artificial support and circulatory collapse requiring vasopressors.4 Hypophosphataemia below 0.05 mmol/l has been found to be an independent predictive factor for acute liver failure in heat stroke.5 The main problem in clinical practice lies in the indication for LT. In a clinical picture of liver failure, delaying LT may result in a patient's death. However, the decision should not be made with haste, since, as seen in this case, full recovery is possible in spite of serious liver (and multiorgan) failure. Evaluation of clinical course and prothrombin time on days 3 and 4 is key to decision-making around LT, as improvement is usually seen as of that time.2,3

Please cite this article as: Ladrón Abia P, Minguez Sabater A, Martinez Delgado S, Berenguer Haym MC. Golpe de calor y hepatitis fulminante: ¿manejo conservador o trasplante hepático? Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:243–244.