Retrospective studies have suggested that long-term use of opioids can cause esophageal motility dysfunction. A recent clinical entity known as opioid-induced esophageal dysfunction (OIED) has been postulated. There is no data from prospective studies assessing the incidence of opioid-induced effects on the esophagus.

AimEvaluate the incidence of OIED during chronic opioid therapy.

MethodsFrom February 2017 to August 2018, all patients seen in the Pain Unit of the hospital, who started opioid treatment for chronic non-neoplastic pain and who did not present esophageal symptoms previously, were included. The presence of esophageal symptoms was assessed using the Eckardt score after 3 months and 1 year since the start of the study. In February 2021, the clinical records of all included patients were reviewed to assess whether esophageal symptoms were present and whether opioid therapy was continued. In patients presenting with esophageal symptoms, an endoscopy was performed and, if normal, a high-resolution esophageal manometry was performed. For a confidence level of 95%, a 4% margin of error and an estimated prevalence of 4%, a sample size of 92 patients was calculated.

Results100 patients were included and followed while taking opioids, for a median of 31 months with a range between 4 and 48 months. Three women presented with dysphagia during the first 3 months of treatment, being diagnosed with esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction; type II and type III achalasia. The cumulative incidence of OIED was 3%; 95%-CI: 0–6%.

ConclusionsChronic opioid therapy in patients with chronic non-neoplastic pain is associated with symptomatic esophageal dysfunction.

Estudios retrospectivos han sugerido que el uso crónico de opiáceos puede causar disfunción esofágica. Se ha postulado una entidad clínica reciente denominada disfunción esofágica inducida por opioides (DEIO). No existen estudios prospectivos que evalúen la incidencia de esta entidad.

ObjetivoEvaluar la incidencia de DEIO durante el tratamiento crónico con opiáceos.

MétodosDesde febrero de 2017 hasta agosto de 2018, se incluyeron todos los pacientes atendidos en la Unidad del Dolor de nuestro hospital, que iniciaron opiáceos por dolor crónico no neoplásico sin síntomas esofágicos previos. La clínica esofágica se valoró mediante la escala de Eckardt a los tres meses y al año. En febrero de 2021, se revisaron las historias clínicas de todos los pacientes para evaluar la presencia de clínica esofágica y si continuaban con opiáceos. En los pacientes con síntomas esofágicos, se realizó una gastroscopia y, si era normal, una manometría esofágica de alta resolución. Para un nivel de confianza del 95%, una precisión del 4% y una prevalencia estimada del 4%, se calculó un tamaño muestral de 92 pacientes.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 100 pacientes que fueron seguidos mientras tomaban opiáceos, con una mediana de 31 meses y un rango entre 4 y 48 meses. Tres mujeres presentaron un trastorno motor esofágico durante el seguimiento (obstrucción funcional de la unión esofagogástrica; acalasia tipo II y tipo III). La incidencia acumulada fue del 3%; IC 95%: 0-6%.

ConclusionesEl tratamiento crónico con opiáceos en pacientes con dolor crónico no neoplásico se asocia a disfunción esofágica sintomática.

The use of opioids is becoming more frequent in the general population, due to the increase in chronic pathologies that result in chronic pain. Long-term consumption of opioids due to cancer-related pain or non-tumor chronic pain has been associated with a variety of adverse effects on the gastrointestinal tract. Their effects take place mainly on the enteric nervous system, through receptors in the myenteric and submucosal plexuses. There are 3 recognized main opium receptors (mu, kappa and delta) that are expressed in the central and enteric nervous systems, which mediate the gastrointestinal effects. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction is a widely known adverse effect, with constipation being the most common manifestation, due to the greater understanding of opium-receptor physiology in the colon. However, their effect on esophageal motility is less known.

Retrospective studies1–5 have suggested that long-term use of opioids can cause esophageal motility dysfunction, such as achalasia and functional esophagogastric junction (EGJ) outflow obstruction.

Various studies with healthy volunteers have shown increased baseline lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure with incomplete relaxation when administering opioids. Kraichely et al.,2 confirmed these findings in clinical practice in a retrospective study of 15 patients with dysphagia and opioid consumption when a manometry was performed. Based on these studies, a recent clinical entity known as opioid-induced esophageal dysfunction (OIED) has been postulated.

The mechanism responsible for the effects of opioids on esophageal motility remains unclear; however, the nitric oxide pathway has been suggested to play an important role.

A retrospective article has recently been published,6 describing a 32% prevalence of OIED in chronic active opioid users. Neither the incidence of OIED nor the profile of patients who may be more frequently affected is known. The study was designed to prospectively evaluate the incidence of esophageal symptoms in patients under chronic treatment with opioids and to define the esophageal motility disorders associated with the use of these drugs.

Patients and methodsStudy designA prospective post-authorization follow-up study in patients who initiated chronic opioid treatment between February 2017 and August 2018 for chronic non-neoplastic pain (Minimum duration of therapy of 90 days) in a tertiary university hospital was designed. Those patients initiating treatment with major opioids for chronic non-neoplastic pain attending one consultation of the Pain Unit of the hospital were consecutively included in the study.

Clinical variables were collected by telephone interview administering a validated quantitative measurement score on esophageal symptoms, Eckardt Score,7 at baseline and 3–12 months after beginning opioid treatment. In addition, a complete digestive clinical history was obtained. The Eckardt score ranges from a minimum score of 0 points to a maximum of 12 points depending on the frequency of dysphagia, regurgitation and chest pain, together with weight loss.

In those patients in whom esophageal symptoms were detected, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with esophageal biopsies would be performed and, if normal, high-resolution manometry (HRM) was also performed. Other procedures, such as esophageal impedance-pH monitoring, were performed as required. Subsequently, a prospective follow-up of all included patients was carried out in February 2021 with the aim of analyzing the occurrence of OIED.

Study populationInclusion criteria were: aged 18 years or more and initiation of chronic treatment with a single major opioid (Morphine, Fentanyl, Tapentadol, Hydromorphone, Methadone and Oxycodone) with a minimum expected treatment duration of 90 days for chronic non-neoplastic pain.

Exclusion criteria were patients with an already established diagnosis of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease or esophageal motor disorders, patients under treatment with minor opiates (tramadol, codeine), patients with an inability to understand the questionnaire, and patients who had previously received opioid treatment.

Statistical analysisQualitative data are expressed as numbers and percentages. Quantitative data are described as median and range.

The risk (cumulative incidence) at 3 months after initiating opioid treatment was calculated with its corresponding 95% confidence interval. The incidence rate was also calculated for the whole duration of the follow-up.

Sample size calculationThe sample size was calculated with a confidence level of 95% and a 4% margin of error. According to our clinical experience, we estimated the incidence of OIED at 4%. Thus, the required sample size was 92 patients. Furthermore, for an estimated proportion of losses of 10%, the loss-adjusted sample should be 102 patients.

Ethical statementThe Ethics Committees of the hospital reviewed and approved the study protocol. All included patients signed informed consent authorizing the use of their clinical data for research purposes. Additionally, the study complies with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Helsinki Declaration.

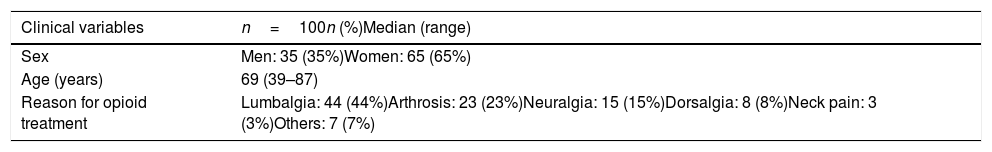

ResultsClinical characteristics of patientsThe clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

A total of 105 patients were initially included, but 5 of them were excluded due to the occurrence of non-esophageal opioid adverse events, which forced withdrawal of treatment during the first 3 months.

Among the 100 patients evaluated in the study, 65 were women and 35 were men with an average age of 69 years.

As shown in Table 1, the most frequent reasons for opioid therapy were lumbar pain (44%), osteoarthritis (23%) and neuralgia (15%).

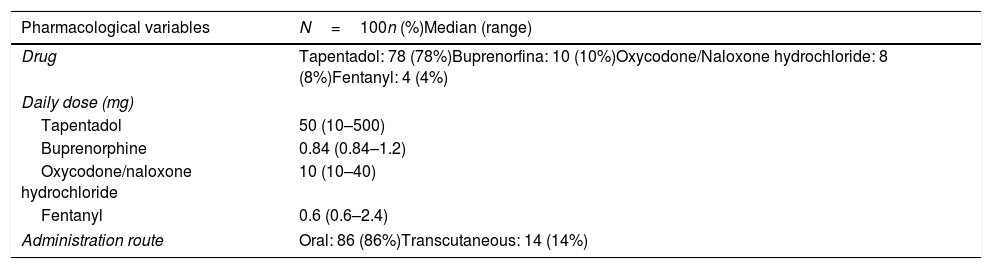

Characteristics of opioidsThe pharmacological variables are shown in Table 2.

Descriptive study of pharmacological variables.

| Pharmacological variables | N=100n (%)Median (range) |

|---|---|

| Drug | Tapentadol: 78 (78%)Buprenorfina: 10 (10%)Oxycodone/Naloxone hydrochloride: 8 (8%)Fentanyl: 4 (4%) |

| Daily dose (mg) | |

| Tapentadol | 50 (10–500) |

| Buprenorphine | 0.84 (0.84–1.2) |

| Oxycodone/naloxone hydrochloride | 10 (10–40) |

| Fentanyl | 0.6 (0.6–2.4) |

| Administration route | Oral: 86 (86%)Transcutaneous: 14 (14%) |

The most frequent active ingredient used was tapentadol (78%). The most common dose (median and range) was 50mg (10–500mg) per day. The administration was oral, except for the patients who received buprenorphine (10%) and fentanyl (4%) whose route of administration was transcutaneous.

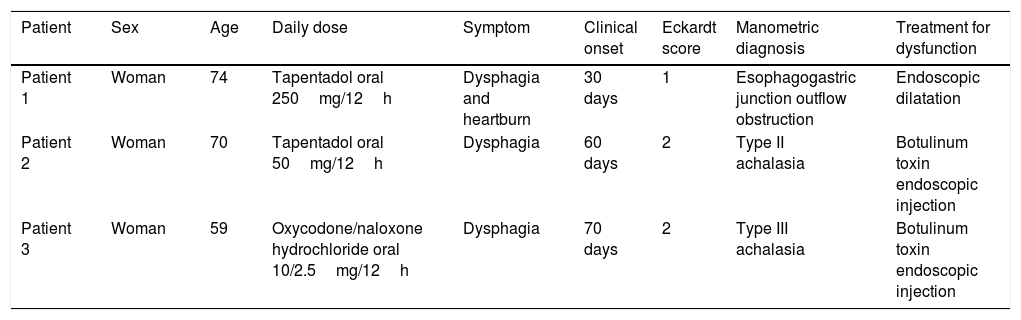

Patients with esophageal symptoms after initiation of opioid therapyNone of the patients had esophageal symptoms at the beginning of treatment and any of the studied population had previously been on opioid therapy prior to a visit to the pain clinic. The Eckardt score performed on all patients at the beginning of treatment was 0 points. After 90 days from the start of the opioid treatment, when the Eckardt questionnaire was administered for a second time, 3 patients reported the appearance of esophageal symptoms, with an estimated risk of 3%; a 95% Confidence Interval of 0–6%. Table 3 summarize clinical data in these patients.

Patients with esophagal dysfunction during follow up.

| Patient | Sex | Age | Daily dose | Symptom | Clinical onset | Eckardt score | Manometric diagnosis | Treatment for dysfunction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Woman | 74 | Tapentadol oral 250mg/12h | Dysphagia and heartburn | 30 days | 1 | Esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction | Endoscopic dilatation |

| Patient 2 | Woman | 70 | Tapentadol oral 50mg/12h | Dysphagia | 60 days | 2 | Type II achalasia | Botulinum toxin endoscopic injection |

| Patient 3 | Woman | 59 | Oxycodone/naloxone hydrochloride oral 10/2.5mg/12h | Dysphagia | 70 days | 2 | Type III achalasia | Botulinum toxin endoscopic injection |

All three patients were women and had a normal upper endoscopy. A high-resolution manometry (HRM) was performed and the Chicago criteria according to version 3.08 were applied at the moment of diagnosis. Esophageal biopsies were taken to rule out other underlying etiologies like eosinophilic esophagitis which could contribute to the symptoms. Esophageal biopsies were normal in all 3 patients.

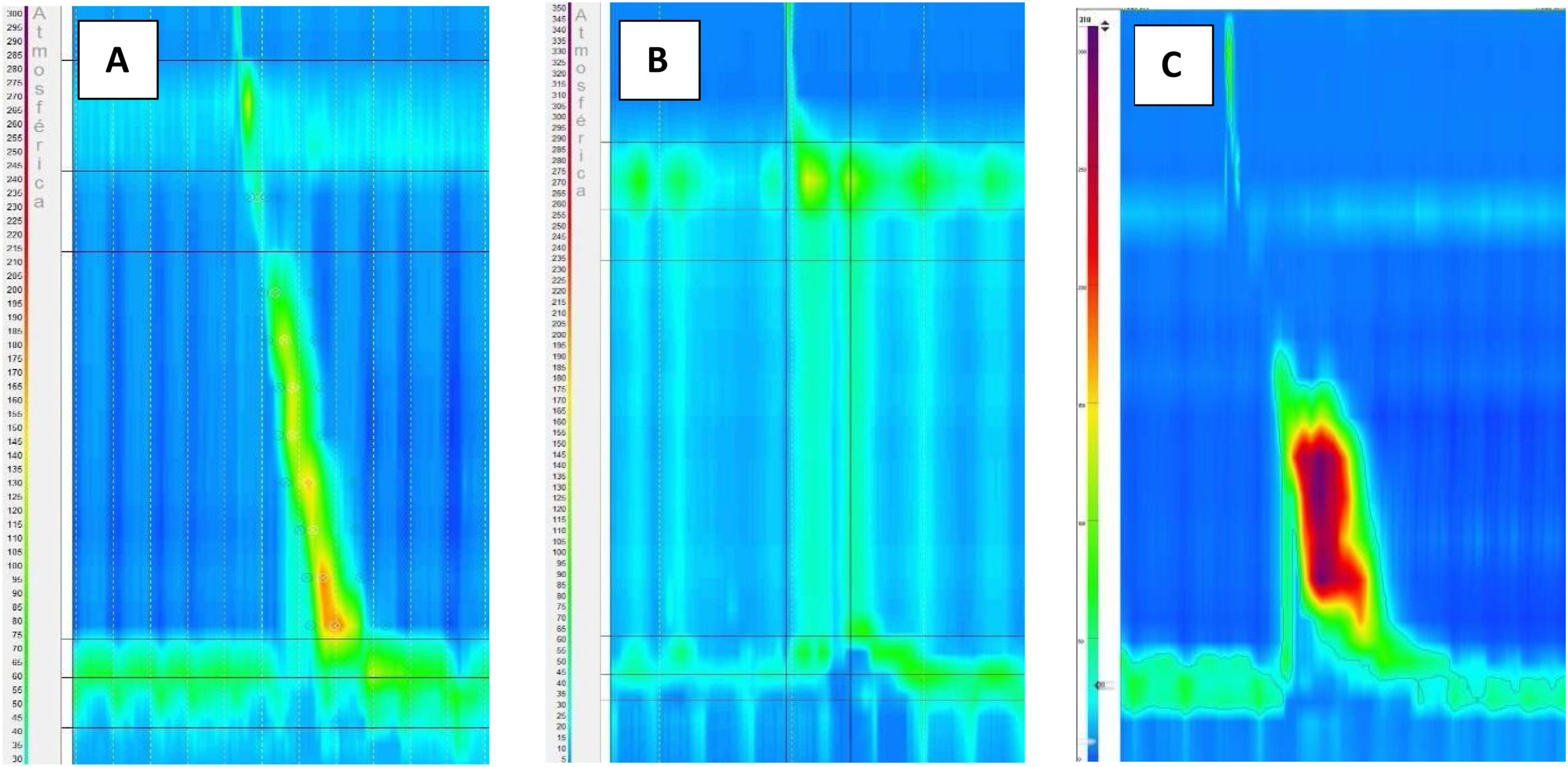

In the case of the first patient, who began suffering from dysphagia and heartburn, the manometric diagnosis was esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO) (Fig. 1A). A timed barium esophagram was performed, showing the delayed passage of contrast from the lower third of the esophagus to the stomach, supporting the diagnosis of EGJOO. The opiate could be withdrawn and endoscopic dilatation was performed with an improvement of dysphagia and heartburn (Eckardt score: 1 point). A control manometry was performed 6 months after treatment and showed a decrease in median IRP and baseline LES pressure.

In the second patient, a diagnosis of type II Achalasia was established by HRM (Fig. 1B). After interrupting opiate treatment, dysphagia improved partially. Finally, she was treated with a botulinum toxin endoscopic injection, with complete resolution of dysphagia (Eckardt score: 0 points). A control manometry was performed 6 months after treatment and showed a normal median IRP and a baseline LES pressure.

In the case of the third patient, the diagnosis of type III Achalasia (Fig. 1C) was established. Opioids could not be withdrawn due to the pain being refractory to other analgesic treatments, but the dose was reduced by half. She was treated with botulinum toxin with clinical improvement (Eckardt score: 0 points). A control manometry was performed 6 months after treatment and showed IRP within the normal range and a decrease in baseline LES pressure.

All of the 100 patients included were followed until February 2021. We analyzed whether patients were still on opioids in February 2021; if they were not, we noted the date of opioid withdrawal. The median time on opioid treatment was 31 months with a range between 4 and 48 months.

Of the 97 patients who were free of symptoms 3 months after the opioid initiation, two patients on active opioid treatment presented dysphagia (Eckardt score: 2 points) during a subsequent follow-up. In the first case, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed. Esophageal candidiasis was diagnosed with a resolution of dysphagia with antifungal treatment (Eckardt score: 0 points). In the second case, a gastroscopy and HRM were performed, which were normal. Finally, a videofluoroscopic swallowing study was performed, establishing a diagnosis of oropharyngeal dysphagia that improved with dietary modifications (Eckardt score: 0 points). The remaining patients remained asymptomatic, with an Eckardt score of 0 points at the end of the follow-up.

At the end of follow-up, 48% of the patients continued opioid treatment. The incidence rate was 0.014 cases of OIED per patient-year under opioid therapy.

DiscussionTo our knowledge, this is the first prospective study designed to analyze the incidence of OIED in chronic opioid-using patients. The estimated risk of OIED after 3 months since the start of opioid therapy in our prospective study was 3%; with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0–6%.

There is a continuous increase in chronic opioid use in the population worldwide, which means that the impact of the side effects of these drugs is increasing over time.9 Regarding published studies evaluating esophageal side effects of chronic use of opioids, the study by Ratuapli et al.,5 in 2015 was the first to employ HRM. Previously published data was based on studies using conventional manometry to evaluate esophageal motor function.2,10,11 The two main studies published about OIED,5,12 concluded that chronic opioid use produced altered relaxation and increased basal LES pressure, corresponding in most cases to type III achalasia and functional obstruction of the esophagogastric junction according to Chicago Classification v3.0. In our prospective study, out of three patients who presented OIED during the follow-up, all of them presented an elevated IRP, with increased basal LES pressure, fulfilling diagnostic criteria for type II and III achalasia, and EGJOO. Manometric diagnosis would have been the same if Chicago Classification v 4.0 had been used.

The symptomatology of patients who develop OIED is diverse. In our study, like others previously published,2,5,10–13 dysphagia was the most frequent symptom. There is little published data regarding the treatment of OIED. It has been described that the first therapeutic measure to be taken is to consider opioid withdrawal. The study by Wu et al.,14 performing an esophageal manometry after 1 month, showed a resolution of the esophageal disorder on those occasions where the drug was withdrawn. If treatment cannot be withdrawn, therapies aimed at reducing LES pressure such as calcium antagonist drugs,14 botulinum toxin, pneumatic dilatation or surgery could be considered. It has been suggested that the efficacy of these treatments is inferior compared to that in non-opioid-using patients.14,15 In our study, opioid withdrawal was possible in 2 of 3 patients, with subsequent partial clinical improvement. Opioid withdrawal should be considered initially in patients who develop dysphagia, and clinical response should be assessed. The two cases of achalasia were treated with periodic sessions of botulinum toxin with good clinical response.

A limitation of our study was that the clinical data observed did not allow us to conclude with certainty that opioids were the sole cause for developing an esophageal motor disorder. However, the fact that dysphagia appeared after the initiation of opioid treatment strongly supports that these drugs played a significant role in the etiopathogenesis of motor disorders. Furthermore, after opioid withdrawal or tapering, post-treatment control manometry showed a decrease in IRP and baseline LES pressure.

In conclusion, our results support the appearance of symptomatic esophageal dysfunction in a reduced number of patients receiving chronic opioid therapy for non-neoplastic conditions. Esophageal dysfunction tends to appear shortly, before 3 months after initiating opioid therapy. Given the high use of opiates, its administration should be investigated in patients presenting with esophageal symptoms. Longer studies with larger samples will help shed light on the impact of opioids on esophageal dysfunction.

FundingThe authors have not received any funding.

Human rights statement and informed consentAll procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent or substitute for it was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare