Social cognition (SC) plays a fundamental role in interpersonal functioning and is often impaired in severe mental disorders like schizophrenia. The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT) is a reliable tool for assessing SC through audiovisual vignettes, but a validated Spanish version was lacking. This study aimed to translate, adapt, and validate TASIT for Spanish-speaking populations.

MethodA cross-sectional study was conducted with 659 participants, including healthy individuals and people with schizophrenia. The TASIT was translated and adapted following a rigorous procedure with the participation and guidance of the original author. Reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity were assessed using established psychometric tools.

ResultsThe Spanish version of TASIT demonstrated strong internal consistency across all sections, with McDonald’s omega coefficients ranging from ω = 0.71 to 0.89. Test-retest reliability was excellent, with correlation coefficients ranging from r = 0.81 to 0.87 (all p < .001). Convergent validity was supported by significant correlations with established social cognition measures (p < .05), and discriminant validity was confirmed by significant performance differences between healthy participants and those with schizophrenia (p < .05).

ConclusionsThe Spanish TASIT is a valid and reliable tool for assessing SC, with strong psychometric properties. It is suitable for both clinical and research settings.

Social cognition (SC) encompasses the mental processes that underpin social interactions, representing a unique cognitive domain evolved to address social and adaptive challenges in daily life.1,2 SC involves how individuals perceive, interpret, and respond to social information, forming a critical component of functioning.3,4 It is considered a multidimensional construct that encompasses key abilities such as emotional processing, theory of mind (ToM), social perception and knowledge and attributional style, all supported by distinct neural networks.5-8 Impairments in SC significantly affect interpersonal relationships and are prevalent in severe mental disorders such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.9,10

Deficits in SC are not only pervasive but also deeply impact patient functioning, making them a critical target for interventions aimed at improving recovery, particularly in schizophrenia11 (Green, 2016). Although no definitive gold-standard treatment exists, several interventions have shown promise in enhancing social cognition abilities.12

The Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) initiative recognized the critical importance of this domain, identifying social cognition (SC) as one of the seven cognitive domains impacted by schizophrenia.13 Likewise, SC is assessed using the "managing emotions" branch of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT).14 Although various tools are available to evaluate specific aspects of SC, such as emotion processing, social perception, ToM, and attributional bias,15-17 the absence of well- validated instruments for the comprehensive assessment of SC remains a significant challenge.18,19

To address this limitation, the Social Cognition Psychometric Evaluation (SCOPE) initiative has identified eight reliable tasks suitable for use in clinical trials and routine practice for individuals with schizophrenia.17,20–22

The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT),23 one of the psychometric instruments selected by the SCOPE initiative, was originally developed to assess social perception in individuals with traumatic brain injury24 and has since been also used in people with schizophrenia.25 TASIT is an audiovisual, multimodal tool consisting of videotaped vignettes depicting everyday social interactions. It is divided into three parts and evaluates two critical domains of SC: emotional processing and ToM.

TASIT offers notable advantages over other tools by integrating information from facial expressions, vocal tones, gestures, and contextual cues, providing a more ecological assessment that closely reflects real-world social interactions. Furthermore, it includes two alternative versions to minimize learning effects, enabling reliable pre- and post- treatment evaluations. Its straightforward format allows for administration by non- high specialized personnel, making it a practical and efficient instrument for clinical applications.23

Therefore, the aim of this study was to translate, adapt, and validate the TASIT for application in Spanish-speaking population.

Methods participantsThe present study employed a cross-sectional design conducted across three distinct work settings in Spain: Miguel Hernández University, Catholic University of Valencia San Vicente Mártir, and the Psychiatric Outpatient Service of San Juan Hospital. Participants were recruited through advertisements posted on the official websites of the participating settings and in psychiatric outpatient clinics. Prior to enrollment, all participants were thoroughly informed about the study's objectives and procedures and provided written informed consent. They were also informed of the main inclusion and exclusion criteria, such as age range (18–65 years), fluency in Spanish, and absence of neurological or active substance use disorders. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Project Evaluation Service of Universidad Miguel Hernández and the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Hospital de San Juan. The study was conducted in strict adherence to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring the protection of participants’ rights and the integrity of the research process.

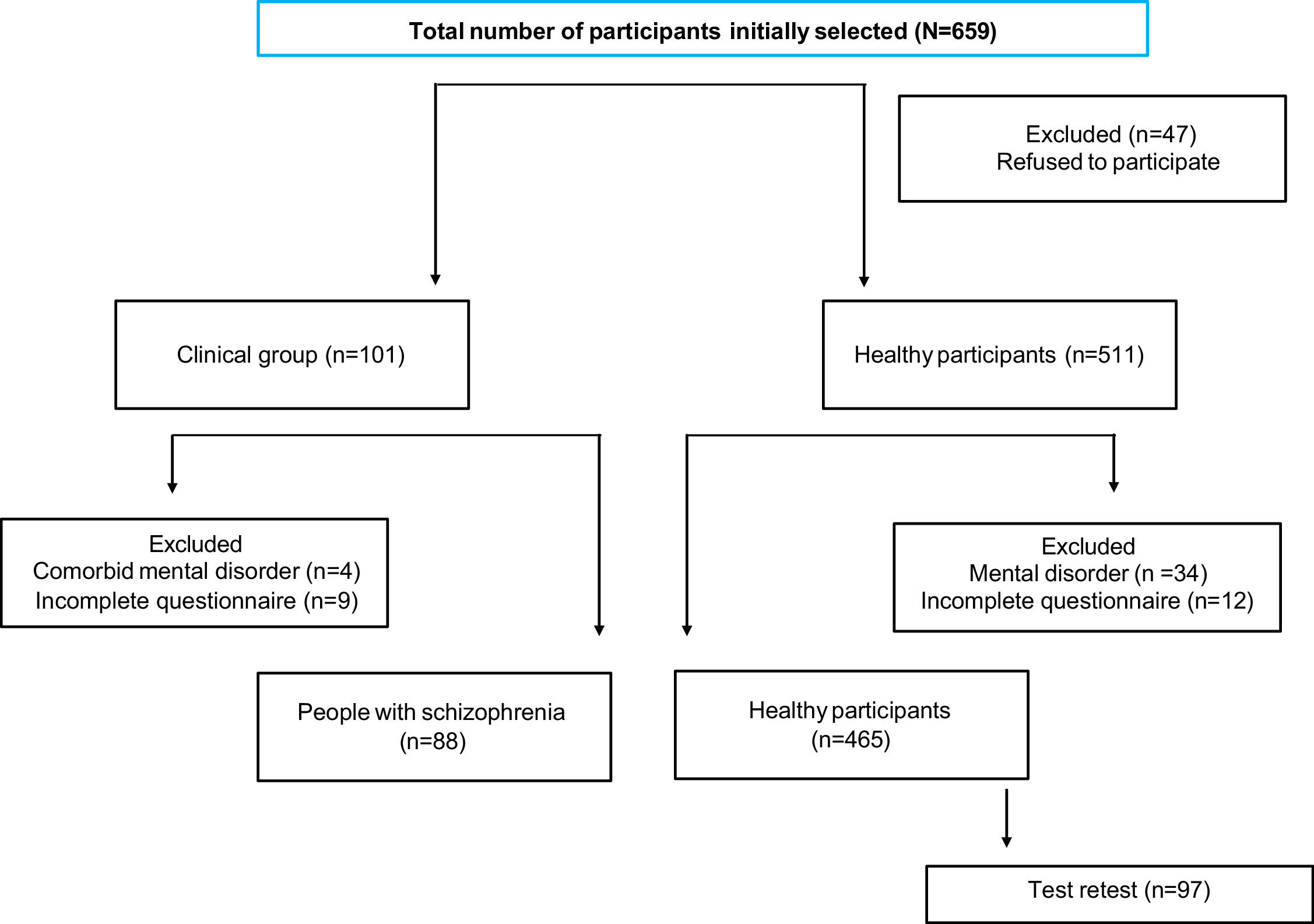

A total of 659 participants were enrolled in the study and subsequently categorized into two groups: healthy participants (HP) and patients with schizophrenia (SCH). Although an initial sample of 659 individuals was recruited, the final analytic sample was reduced following the exclusion of participants due to refusal to participate, presence of comorbid mental disorders, or incomplete data, as detailed in the flow diagram (Fig. 1). Participants were classified into two final groups based on diagnostic status: healthy individuals (n = 511) and patients with schizophrenia (n = 101).The HP group included individuals aged 18–65 years with no current or past major psychiatric disorders, as assessed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (Sheehan et al., 1997), and with proficiency in spoken Spanish. The SCH group included patients aged 18–65 years with a diagnosis of schizophrenia based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),26 assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders (SCID-5-RV),27 who were clinically stable (stability was defined as the absence of significant clinical changes in symptomatology, as recorded in the patient's medical file, along with no modifications in treatment and no hospitalizations, as described in previous studies from our research group)28 and fluent in Spanish. Exclusion criteria for both groups included the presence of any neurological disorder or active substance use disorder, except for nicotine or caffeine use, and refusal to participate.

Fig. 1 presents a data flow diagram illustrating the selection, evaluation, exclusion, and analysis of participants.

InstrumentsSociodemographic data on age, gender and o educational level were collected for all study participants, and the following instruments were administered:

The awareness of social inference test (TASIT)The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT)23 is a video- based assessment tool designed to evaluate social perception and pragmatic language skills through 59 vignettes depicting everyday social interactions. It is divided into three sections, each available in two alternative forms (TASIT-A and TASIT-B):

Emotion Evaluation Test (EET): This section assesses the recognition of spontaneous emotional expressions through 28 video scenes, including 12 positive and 16 negative emotional displays. One or two actors portray various emotions, and participants are required to identify the emotion that best matches the vignette from seven options: happy, surprised, sad, anxious, angry, disgusted, and neutral.

Social Minimal Inference Test (SI-M): This section evaluates the comprehension of sincerity versus sarcasm across 15 video scenes. The scenes feature interactions between two actors, categorized into three types: sincere exchanges (5 scenes), simple sarcasm (5 scenes), and paradoxical sarcasm (5 scenes).

Enriched Social Inference Test (SI-E): This section examines the ability to distinguish lies from sarcasm through 16 video scenes, where 8 depict lying exchanges and 8 depict sarcastic exchanges. Additional contextual information is provided through either visual signals (e.g., images that reveal the truth) or prologues/epilogues (where one actor discloses their true thoughts or feelings to a third party).

In both the SI-M and SI-E sections, participants rely on speaker demeanor (e.g., voice tone, facial expressions) to interpret the intended meaning. Following each scene, participants respond to four probe questions about what the actors "do," "say," "think," and "feel," with answer options of “yes”, “no”, or “don't know”. These questions assess participants' understanding of the emotions, intentions, beliefs, and meanings conveyed by the actors in the interactions.

The reading the mind in the eyes test (RMET)The RMET29 evaluates the ability to infer complex emotions from the eye region of 36 black-and-white photographs of male and female individuals of varying ages. Participants select the emotion that best represents what the person in the photograph is thinking or feeling from four provided options, of which only one is correct. To minimize reliance on vocabulary, this study followed SCOPE recommendations20-22 by providing definitions of the emotions alongside the task.

Theory of mind picture stories task (ToM PST)The ToM PST30 assesses the ability to understand mental states through six cartoon stories, each divided into four vignettes presented on individual cards in random order. Participants are tasked with sequencing the vignettes logically to form a coherent story. If sequencing is incorrect, the interviewer corrects the order to proceed. Participants are then asked questions about the story to evaluate their understanding of the characters’ mental states and intentions.

Interpersonal reactivity index (IRI)The IRI31 is a 28-item questionnaire that measures empathy on a multidimensional scale. Items are rated on a Likert scale from 0 ("does not describe me well") to 4 ("describes me very well"). The IRI provides four subscale scores: perspective taking, fantasy, empathic concern, and personal distress, as well as composite scores for cognitive empathy and affective empathy.

ProcedureThe study was conducted in four phases:

Translation and Adaptation: TASIT was translated and dubbed into Spanish using the original scripts provided by the original author. A bilingual professional conducted the initial English-to-Spanish translation, followed by a back-translation to English by a native speaker. A third bilingual expert ensured accuracy by comparing the original and translated versions. The final version was reviewed and approved by the original author of the TASIT. In addition, the finalized scripts for all 59 scenes were professionally dubbed. The research team and dubbing specialists reviewed the recordings for accuracy. A pilot test involving 21 participants, separate from the main study sample, was conducted to evaluate comprehension and applicability. All participants demonstrated a clear understanding of both the scenes and accompanying text, with no reported limitations or discrepancies.

Selection and Randomization: HP were randomly assigned to TASIT-A (n = 208) or TASIT-B (n = 257) using a computer-based randomization system.

Evaluation: Baseline assessments were conducted in a single two-hour session, with all participants evaluated under similar conditions.

Test-Retest: To evaluate reliability, 100 healthy participants were invited by the research team to voluntarily complete the same TASIT version [TASIT-A (n = 34) or TASIT-B (n = 63)] in a second session. Of these, 97 agreed to participate. This follow-up session, conducted 14–21 days after the baseline assessment, lasted one hour and was carried out under identical conditions to the initial evaluation.

Data analysisStatistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0 for Windows. Reliability analyses were conducted using JASP software (version 0.16). Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics, mean and SD for quantitative variables and % for qualitative variables. Internal consistency was estimated using McDonald’s Omega coefficient. Test-retest reliability was assessed using Pearson's correlation coefficient. To evaluate convergent validity, partial correlations controlling for age, sex, and educational level were computed between TASIT subscales and RMET, ToM PST, and IRI subscales. Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the means of healthy participants with those diagnosed with schizophrenia using ANCOVA models, also adjusting for age, sex, and education as covariates, to ensure that group differences were not confounded by these variables.

ResultsSample characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of healthy participants and participants with schizophrenia.

TASIT: The Awareness of Social Inference Test; M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

Internal reliability levels were found to be satisfactory across all sections of the TASIT, following established standards.32 In Part 1, comprising 28 categorized items with dichotomous outcomes, McDonald’s omega coefficients were calculated as ω = 0.71 for TASIT-A and ω = 0.89 for TASIT-B. For Part 2, consisting of 60 questions grouped into 15 blocks of 4 dichotomous questions each, the McDonald’s omega coefficients were ω = 0.75 for Form A and ω = 0.87 for Form B. Finally, in Part 3, which includes 64 questions organized into 16 blocks of 4 dichotomous questions each, McDonald’s omega coefficients were ω = 0.74 for Form A and ω = 0.75 for Form B.

Test-retest reliabilityThe results presented in the Table 2 show the test-retest reliability for the TASIT-A and TASIT-B subtests in healthy participants. For TASIT-A, the means for the initial test and retest are highly consistent across all subtests (EET, SI-M, SI-E), with no significant differences observed (p > .05) and high correlation coefficients ranging from r = 0.82 to r = 0.87, all statistically significant (p = .000). Similarly, for TASIT-B, the correlations were also high (r = 0.81 to r = 0.87, p = .000), indicating strong test-retest reliability. However, a significant mean difference was observed in Part 3 (SI-E) of TASIT-B, with a t value of −2.694 and p = .009, suggesting a potential instability in this subtest. Overall, the high correlation values and the minimal differences in most subtests indicate strong test-retest reliability for the TASIT measures.

Test-retest reliability coefficients and mean differences for test–retest measurement of TASIT–A and TASIT–B in healthy participants.

TASIT: The Awareness of Social Inference Test; M: mean; SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval; EET: Emotion Evaluation Test; SI–M: Social Inference–Minimal; SI–E = Social Inference–Enriched; a: T test; b: Wilcoxon; c: Pearson; d: Spearman.

Convergent validity was established through significant relationships between the TASIT and other Theory of Mind (ToM) measures (p < .05) (Table 3). The RMET test demonstrated significant correlations with Parts 1 and 3 of the TASIT. Additionally, a positive and statistically significant association was observed between the ToM PST and all parts of TASIT-A. Furthermore, various dimensions of the IRI questionnaire showed significant correlations with both TASIT-A and TASIT-B.

Pearson's between TASIT A and TASIT B and social cognition and empathy measures in healthy participants.

EET: Emotion Evaluation Test; SI–M: Social Inference–Minimal; SI–E: Social Inference–Enriched; RMET: Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test; ToM PST: ToM Picture Stories Task; IRI: Interpersonal Reactivity Index; PT: Perspective taking; FS: Fantasy; EC: Empathic concern; PD: Personal distress; CE: Cognitive empathy; AE: Affective empathy.

*p < .05; ** p < .01; ***p < .001 (two-tailed).

Discriminant validity was evaluated by comparing the scores of healthy participants with those of participants with schizophrenia. The TASIT effectively distinguished between the two groups (p < .05), as shown in Table 4. The clinical group exhibited significantly lower performance than the healthy participants across all subtests—EET, SI-M, and SI-E—on both Form A and Form B of the TASIT, highlighting its sensitivity in detecting performance differences between clinical and non-clinical populations.

Comparison of healthy participants and participants with schizophrenia.

M: mean; SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval; EET: Emotion Evaluation Test; SI–M: Social Inference–Minimal; SI–E: Social Inference–Enriched.

Social cognition has emerged as a critical domain for effective functioning within society. Consequently, researchers have emphasized the necessity of utilizing properly developed, valid, and reliable instruments for its measurement.22,33 In this context, the present study sought to translate, adapt, and validate the Spanish version of the TASIT24 in a sample comprising both healthy participants and a group of people with schizophrenia. The findings of this study provide a robust, valid, and sensitive tool, showing adequate psychometric properties for its application among Spanish-speaking populations both in clinical practice and in research settings.

It is noteworthy that the mean scores for each component of TASIT, (forms A and B), in the Spanish-speaking sample were slightly lower than those reported in the original TASIT manual23 for Australian adults (Supplementary Material, Table S1). However, these scores were more similar to those reported by McDonald34 for younger adults. This difference may be attributed to the relatively younger age of the healthy participants in the current study. Another possible explanation is that, in the present study, participants completed all three parts of the scale consecutively in a single session, whereas in the original version, the assessment was fragmented.24 Factors such as attention, fatigue, and tiredness may have slightly contributed to reduced performance in the Spanish sample. Additionally, cultural and linguistic adaptations may have influenced task performance. These findings underscore the importance of contextual factors, such as age and cultural differences, in interpreting social cognition assessments across diverse populations.35,36

Regarding the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of TASIT, the internal consistency across all components of both forms significantly exceeded the standard threshold of 0.70,37 commonly accepted as indicative of adequate reliability. According to Nunnally's32 criteria, these indices strongly support the notion that the items comprising TASIT effectively measure a unified construct and exhibit robust inter- item correlations. Moreover, the reliability coefficient observed in Part 3 of TASIT aligns closely with values reported in other healthy populations21,38 and, in some cases, is slightly higher.20

In response to the concerns raised in the SCOPE study20-22 regarding the equivalence of alternative forms, this study reports test-retest reliability rather than parallel forms. Consistent with findings from the original scale,39 the overall test-retest reliability found in this study was excellent (> 0.81). The high level of agreement observed suggests that both alternative forms demonstrate stability and consistency with repeated administration, as also reported in the original tool.39 On the other hand, the slight improvement in performance on TASIT B (SI-E) may reflect a learning or recall effect. Test-retest reliability was assessed by conducting repeated measurements on the same participants with a time interval between 14 and 21 days, following the baseline assessment, in line with the recommendations of SCOPE.22 This specific time frame was chosen thoughtfully, considering the potential impact of learning effects in shorter intervals and the possible influence of other variables in longer intervals.

The correlation coefficient between the scores obtained on TASIT and those from the other tools used in the study was, although significant, of moderate magnitude. This outcome may be partially influenced by the fact that the instruments selected to assess convergent validity were primarily designed for clinical populations, which could limit their sensitivity to TASIT's unique features when applied to healthy participants. Therefore, these instruments differ significantly from TASIT in format, as they do not include gestural, intonational, and contextual cues. These distinctive elements of TASIT may explain the moderate strength of the observed correlations, highlighting its added value in capturing the nuanced aspects of social cognition.

Moreover, the constructs involved in social cognition are not clearly defined, and as such, the available instruments to assess these domains are not perfectly aligned, as noted by the SCOPE17 initiative. In particular, the relationship between empathy and theory of mind (ToM) remains unclear, with ongoing debate as to whether empathy is a component of ToM or a distinct domain itself.40 Nonetheless, it is well-established that social cognition encompasses empathic abilities,17 and there is a recognized relationship between empathy and ToM, particularly in social cognitive functioning.41

In addition, the Spanish version of the TASIT has also demonstrated its effectiveness as a tool for discriminating between healthy people and those with schizophrenia, supporting findings from studies conducted with this instrument across various neuropsychiatric populations.20,21,38,42–44 Both versions, as well as each of its components, exhibit high sensitivity in detecting individuals with schizophrenia, thereby making it a valuable instrument for both clinical practice and research. Moreover, these attributes underscore its utility in classifying individuals with schizophrenia based on the degree of functional impairment45 and in detecting changes associated with psychotherapeutic46 and pharmacological interventions in individuals with schizophrenia.47

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of a limitations. First, the sample consisted predominantly of young adults, with a relatively low mean age, and a large proportion of participants were recruited from academic settings, particularly universities. This recruitment strategy may limit the generalizability of findings to older or more diverse populations, including individuals with lower educational attainment or different socioeconomic backgrounds. However, the study's strengths include the inclusion of a large sample, and a cohort of clinically stable patie4nts with schizophrenia, which supports the study's discriminant validity.

Additionally, the study benefited from a rigorous translation and dubbing process, closely supervised by the author of the original instrument, ensuring an accurate reproduction of the original content without introducing potential biases. Nonetheless, it is important to consider that subtle cultural and linguistic differences, even when minimized through careful adaptation, may have influenced participants' interpretation of emotional expressions, verbal nuances, or sarcasm. Such factors could contribute to variability in performance when applying the test across distinct Spanish-speaking populations. Future studies should explore cross-cultural equivalence and regional adaptations in greater depth.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to translate, adapt validate and examine the psychometric properties of the TASIT in a broad Spanish-speaking sample. The results indicate that the Spanish version of the TASIT is a reliable and valid tool for assessing emotional recognition and ToM, making it suitable for clinical use in evaluating social cognition in people with schizophrenia. Further researchshould prioritize the development and validation of a shortened or screening version of the TASIT to enhance its feasibility in time-constrained clinical settings. Such an abbreviated tool could facilitate broader adoption by clinicians and improve access to social cognition assessment in routine practice.

Ethical considerationsThis study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the relevant institutional ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion, ensuring confidentiality and the right to withdraw at any time. No identifiable personal data were collected or published.

FundingThis research received no external funding.

Data availability statementThe data presented in this study is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Dr. R. Rodriguez-Jimenez has been a consultant for, spoken in activities of, or received grants from: Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Madrid Regional Government (S2010/BMD-2422 AGES; S2017/BMD-3740; P2022/BMD-7216), Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Ferrer, Juste, Takeda, Exeltis, Casen Recordati, Angelini, and ROVI. No other authors have competing interests.

We extend our sincere gratitude to Sandra Pérez for her invaluable support and methodological guidance throughout the development of this validation. We also wish to thank Bartolomé Pérez Gálvez for providing essential technical assistance in the acquisition and preparation of the instrument, which greatly contributed to the success of this study.