The schizophrenia spectrum is defined as a set of disorders related to psychosis,1 including diagnostic categories marked by the fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).2-4 Among them, the disorder that gives the spectrum its name stands out: schizophrenia. This is a severe mental disorder that affects approximately 1 % (0.3-0.7 %) of the general population5 and is one of the disorders that generates the highest care and economic burden.6 The symptoms of schizophrenia are summarized in three widely studied categories: positive symptoms, frequently characterized by hallucinations and delusional ideas7; negative symptoms, represented by alogia, anhedonia, or apathy8; and disorganized symptoms, with disorganization of language, thought, or behavior.9

Schizophrenia, like many other disorders, is understood dimensionally on a psychotic continuum, with dimensional risk progression models currently prevailing.10 Thus, it has different phases that mark its course: the prodromal, active, and residual phases, respectively.11 Within the prodromal phase, the term High-Risk Mental State (HRMS) was conceptualized to categorize those individuals who, although not having been diagnosed, present symptoms related to the spectrum.12 HRMS can last from 1 to 5 years13 and represents a state of mental vulnerability.14

In recent decades, efforts have focused on investigating prodromal symptoms and signs to improve early detection of psychosis. One of these indicators are ideas of reference, being considered their presence a high-risk criterion for transition to psychosis.15 These attenuated psychotic symptoms are a pathological form of referential thinking,16 a type of self-referential cognitive processing where the subject evaluates whether a neutral stimulus is attributable to themselves.17 Often this process is experienced intrusively, demonstrating cognitive interference in which contextual information is biased, leading the subject to make self-attributions of neutral stimuli (e.g., "people laugh when I walk down the street").17,18 Thus, the subject engages in high-emotion self-reference, thinking that these stimuli are related to themselves,19,20 which is a habitual and reversible cognitive activity in the general population.21,22 However, once ideas of references become stable and there is a greater latency in response when making them, this process becomes pathological and delusional (e.g., "they make comments about me on television").15,23

From a behavioral perspective, this process has been analyzed using both experimental tasks and scales,22 with the REF (Referential Thinking) questionnaire being a prominent tool.21 At the neurobiological level, it is known that schizophrenia involves hypoactivation of the prefrontal cortex.24 Additionally, dysfunction in the set of areas referred to as Cortical Midline Structures (CMS) has been highlighted in relation to certain prodromal symptoms.20 CMS structures are composed by different areas such as anterior pre- and sub-genual cingulate cortex (PACC), supragenual anterior cingulate cortex (SACC), posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), dorsomedial (dmPFC), ventromedial (vmPFC) and orbitomedial (omPFC) prefrontal cortices, medial parietal cortex (MPC), and retrosplenial cortex (RSC).20 Specifically, studies that have focused on referential thinking have highlighted different neural substrates, such as hyperactivation of the medial prefrontal cortex,25 the insula,26 the hippocampus,27 the precuneus,28 and the temporo-parietal junction.29

Currently, the multitude of brain areas related to this process poses a dilemma when trying to understand it at the neurobiological level. Therefore, the main objective of this review is to systematically investigate the proposed neural bases for the deficit in referential thinking in schizophrenia spectrum disorders and in high-risk mental states.

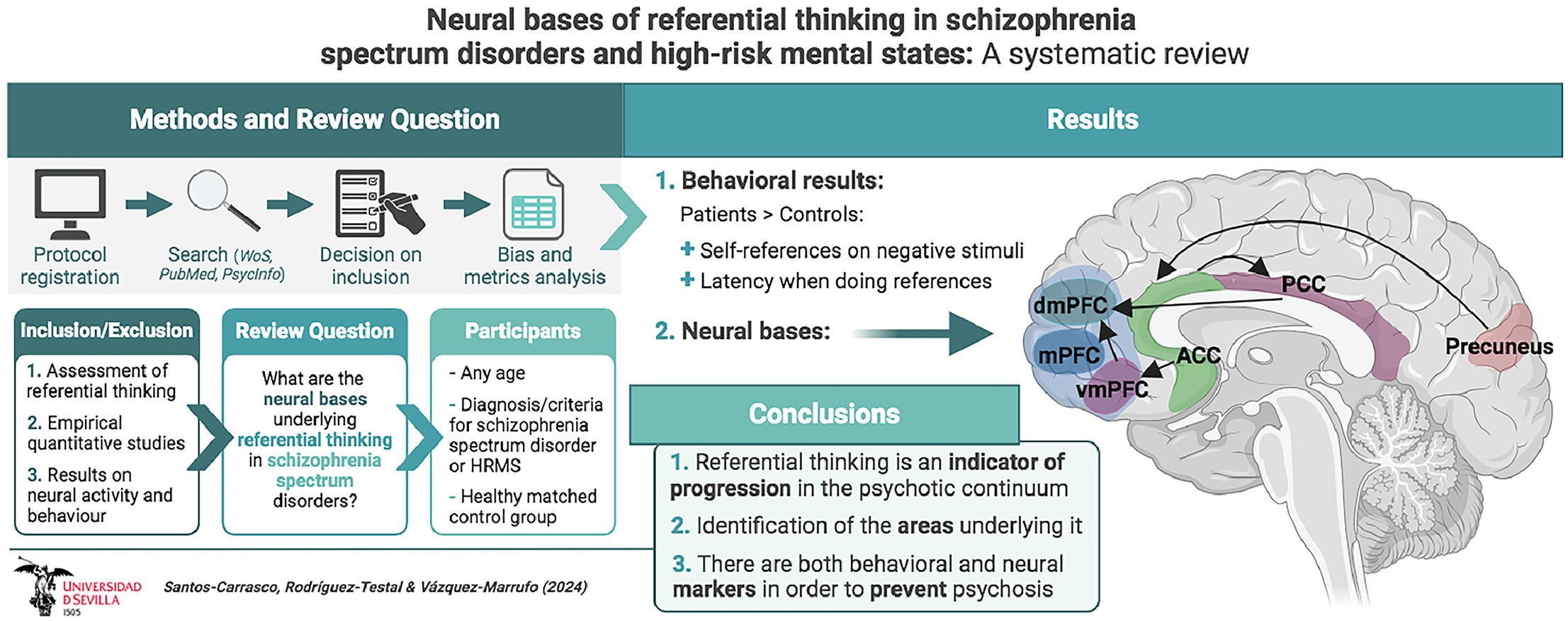

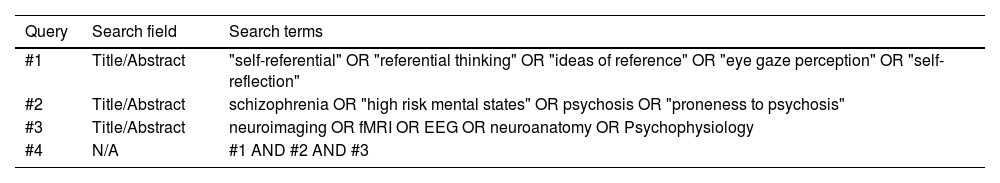

Material and methodsSearch strategyA systematic review of the scientific literature was carried out using the PRISMA 2020 statement,30 verifying compliance with all its criteria. A review protocol was developed and registered in PROSPERO on December 17, 2021 (registration number: CRD42021291691). The search was conducted periodically using the PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycInfo electronic databases, with the first search on September 1, 2022, and the last search on February 29, 2024. The search terms referred to three main query fields: referential thinking, the nervous system, and the schizophrenia spectrum (Table 1). The syntax employed in each consulted database can be observed in Supplementary Material 1.

Search strategy.

Abbreviations: N/A, not applicable.

The inclusion criteria were described using the PICO strategy,31 so to be included in the review: participants (P) were individuals of any age with a diagnosis or who met criteria for a schizophrenia spectrum disorder or an HRMS; for the intervention (I), studies that evaluated referential thinking and the nervous system were sought; regarding the comparator (C), the control group was expected to be composed of individuals without a diagnosis or who did not meet criteria for the aforementioned disorders; finally, the studies were expected to report results (O) on referential thinking and nervous system activity in relation to it. To be included, the studies had to be written in English or Spanish, have an experimental design with a case-control design, and be conducted in a controlled laboratory setting.

Regarding the exclusion criteria, studies not written in English or Spanish were not included, those that did not evaluate referential thinking or the nervous system, those without a comparison group, those with patient groups different from the schizophrenia spectrum, those with designs other than case-control experimental, or those conducted in uncontrolled contexts. The complete set of inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Supplementary Material 2.

Screening and data extraction processAn independent peer review (DSC y MVM) process was carried out to screen and select studies, with a third reviewer (JFRT) resolving any conflicts. Firstly, a title, abstract, and keyword screening was carried out, and then a full-text reading of the selected articles from the previous phase was conducted. Subsequently, a snowballing process was carried out by analyzing the references of the systematic reviews identified in the search and the citations reported on the primary records. A form was designed and used by the independent reviewers to extract data from the records (Supplementary Material 3).

Mendeley (version 1.19.8), Parsifal (parsif.al), and Excel (version 16.43) were used to manage the references. Additionally, Vosviewer software (version 1.6.18) was used to conduct a bibliometric analysis of the records.32

Quality assessmentThe quality of the included studies was analyzed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)33 through an independent peer review process. This scale gives scores from 0 to 9 in star form for the categories of selection, comparability, and exposure, with a higher score indicating a lower risk of bias.34

ResultsGeneral summary of the identified recordsAlthough the study of prodromal symptoms is relatively recent, there is an increasing trend in the number of publications related to this topic (Fig. 1, top). The most prominent keywords among the analyzed records were diverse, referring both to the spectrum of schizophrenia disorders and to the neurodiagnostic techniques used (Fig. 1, bottom).

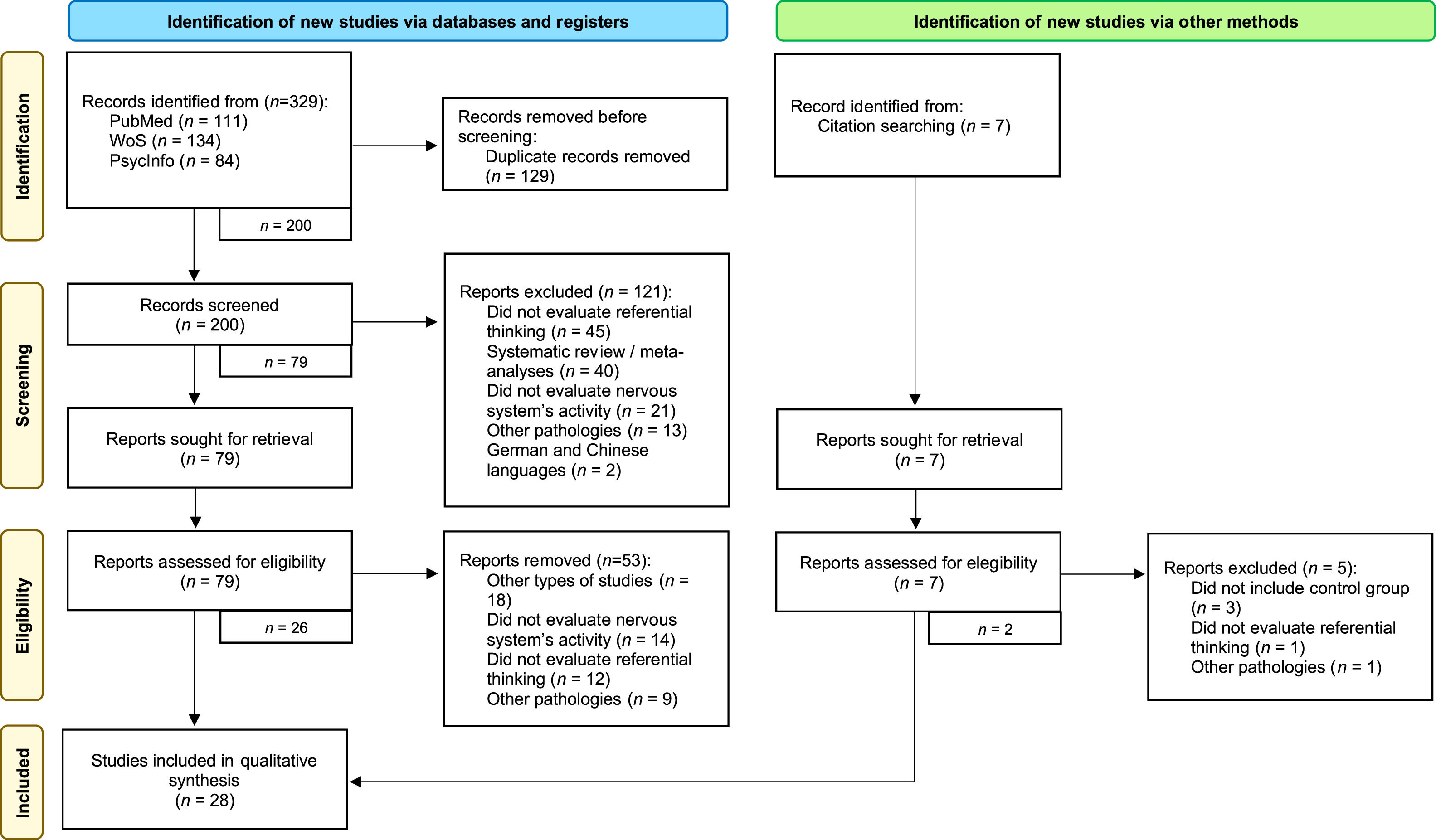

After the search, a total of 329 studies were obtained, of which 129 were excluded as duplicates. Subsequently, 200 studies were screened, of which 121 were discarded for various reasons, such as being systematic reviews or not evaluating referential thinking. After full-text reading, another 53 records were excluded for evaluating other processes, not evaluating nervous system activity, or having participants with other pathologies, among others. The snowball process allowed the recovery of 7 articles, of which 2 were accepted, leaving a total of 28 articles included in the systematic review. A more in-depth analysis of the process can be carried out by observing the flow diagram presented in Fig. 2.

Bibliometric analysisA total of 169 authors were involved in the authorship of the studies included in the review. Among these, A. Aleman, S. Tan, Y. Zhao, M. S. Keshavan, and I. van der Meer stood out. Co-authorship analysis showed that there were three main research groups (Fig. 3), interconnected by M. S. Keshavan. The most cited authors were A. Aleman (256 citations, 51.2 citations per document), I. van der Meer (191 citations, 63.7 citations per document), A. S. David, and G. H. M. Pijnenborg (161 citations, 80.5 citations per document).

The included articles were published in 18 scientific journals, with Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging (4 documents) and Schizophrenia Research (3 documents) having the highest number of publications. The most cited articles were published in the journals of Schizophrenia Bulletin (169 citations in two documents) and Schizophrenia Research (144 citations in 3 documents) (Fig. 4).

Bibliometric analysis map of the journals where the articles have been published.

Note: The size of the dots represents the number of published articles. The color represents the number of citations received by the articles. The lines represent the relationship between different journals based on cross-citations.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the samples of each of the included studies were analyzed (Table 2). The mean sample size was 42 participants (SD = 17.26), which was slightly higher in the patient groups (M = 21.14, SD = 10.82) than in the controls (M = 19.18, SD = 6.52).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | n [n1, n2] | Mean age [n1, n2] | Mean sex [M/F] [n1, n2] | Diagnosis | Criteria / clinical scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collin et al.40 | 34 [15, 19] | 9.4 [9.6, 9.3] | 14/20 [5/10, 9/10] | HRMS | Genetic risk |

| Raju et al.62 | 40 [19, 21] | 30 [33.4, 26.5] | 40/0 [19/0, 21/0] | Schizophrenia | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

| Park et al.39 | 50 [22, 28] | 21.7 [21.8, 21.6] | 31/19 [16/6, 15/13] | HRMS | SIPS Scale |

| Jia et al.59 | 36 [18, 18] | 32.8 [35, 30.7] | 20/16 [11/7, 9/9] | Schizophrenia | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

| Jimenez et al.58 | 36 [20, 16] | 46.5 [48.3, 44.7] | 24/12 [13/7, 11/5] | Schizophrenia | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

| Larivière et al.56 | 42 [27, 15] | 40.3 [41.8, 38.9] | 28/14 [18/9, 10/5] | Schizophrenia | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

| Girard et al.57 | 29 [14, 15] | 38.2 [40.6, 35.9] | 20/9 [10/4, 10/5] | Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder | SAPS Scale |

| Lee et al.54 | 45 [20, 25] | 42.7 [43.9, 41.5] | 30/15 [14/6, 16/9] | Schizophrenia | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

| Pankow et al.53 | 103 [56, 42] | 28.3 [28.5, 28.2] | 71/27 [44/12, 27/15] | Schizophrenia | CIE-10 Criteria |

| Liu et al.48 | 32 [17, 15] | 45.2 [50, 40.5] | 14/18 [6/11, 8/7] | Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

| Zhao et al.49 | 42 [20, 22] | 34.4 [35.6, 33.2] | 22/20 [12/8, 10/12] | Schizophrenia | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

| Schneider et al.37 | 31 [14, 17] | 15.9 [16.1, 15.8] | 19/12 [7/7, 12/5] | HRMS | Genetic risk [22q11DS syndrome] |

| Shad et al.45 | 32 [17, 15] | 37.1 [30, 44.3] | 22/10 [14/3, 8/7] | Schizophrenia | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

| van Buuren et al.36 | 50 [25, 25] | 27.7 [27.9, 27.5] | 18/32 [9/16, 9/16] | HRMS | Genetic risk |

| Modinos et al.35 | 36 [18, 18] | 20.3 [19.8, 20.8] | 20/16 [10/8, 10/8] | HRMS | CAPE Scale |

| Park et al.44 | 29 [14, 15] | 28.8 [29.5, 28.2] | 14/15 [6/8, 8/7] | Schizophrenia | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

| Silva et al.41 | 16 [9, 7] | 29.5 [30.7, 28.4] | Not reported | Schizophrenia | CIE-10 Criteria |

| Fuentes-Claramonte et al.61 | 50 [23, 27] | 37.8 [37, 38.7] | 33/17 [16/7, 17/10] | Schizophrenia | DSM-IV-TR Criteria |

| Furuichi et al.60 | 30 [15, 15] | 27.2 [27, 27.5] | 16/15 [8/7, 8/8] | Schizophrenia | CIE-10 Criteria |

| Damme et al.38 | 42 [22, 20] | 21.1 [20.6, 21.6] | 22/20 [13/9, 9/11] | HRMS | Structured interview |

| Zhang et al.55 | 38 [17, 21] | 32.7 [35.5, 29.9] | 23/15 [11/6, 12/9] | Schizophrenia | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

| Ćurčić‐Blake et al.50 | 64 [45, 19] | 34.5 [35, 34] | 44/20 [34/11, 10/9] | Schizophrenia | MINI-Plus [DSM-IV] |

| Tan et al.51 | 35 [18, 17] | 40.8 [40.5, 41.2] | 21/14 [11/7, 10/7] | Schizophrenia | DSM-IV Criteria |

| Zhang et al.52 | 38 [17, 21] | 32.7 [35.5, 29.9] | 23/15 [11/6, 12/9] | Schizophrenia | MINI-Plus [DSM-IV] |

| Pauly et al.47 | 26 [13, 13] | 35.3 [36.2, 34.4] | 14/12 [7/6, 7/6] | Schizophrenia | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

| van Der Meer et al.46 | 68 [47, 21] | 32.1 [34.3, 30] | 47/21 [35/12, 12/9] | Schizophrenia | MINI-Plus [DSM-IV] |

| Holt et al.43 | 39 [19, 20] | 36.1 [35.7, 36.6] | Not reported | Schizophrenia | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

| Murphy et al.42 | 21 [11, 10] | 28.1 [26.6, 29.6] | 11/9 [7/4, 4/5] | Schizophrenia | SCID-I [DSM-IV] |

Abbreviations: CAPE, Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences-Positive Scale; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition; F, Female; HRMS, High-Risk Mental State; M, Male; n1, patient group; n2, control group; SAPS, Schedule for Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SCID-I, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders; SIPS, Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes.

The patients had a similar mean age (M = 31.12, SD = 9.33) to that of the control group participants (M = 31.29, SD = 8.41). Both groups had a higher proportion of men than women, with 61.68 % and 57.23 % of men in the patient and control groups, respectively.

Regarding the pathology of the patient group, 78 % of the studies had samples with subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia. The rest of the studies evaluated subjects with high-risk mental states.35-40

Referential thinking assessmentThe 28 articles included in the review used experimental paradigms to evaluate this process (Table 3). Among them, a paradigm in which participants had to make a referential decision of a personality adjective stood out (46.43 %). Other paradigms were diverse: asking participants to make references about phrases35,46,50,52,55-60; using adjective recognition tasks49,58,59; or references to dialogues held by third parties,35,45 among others.

Referential thinking: evaluation and results of selected studies.

| Study | Experimental task | Specific contrast | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collin et al.40 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. othersCC: Emotional valence of the adjective | There are no differences between groups in referential thinking |

| Raju et al.62 | Cognitive insight, reference on self-image | Beck's Cognitive Insight Scale [BCIS] | Schizophrenia>Control: Decreased BCIS scores; No differences in referential thinking. |

| Park et al.39 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self [1st/3rd person] vs. familiar [1st/3rd person] | ↑ RT in both groupsHRMS>Control: ↓ Self-references |

| Jia et al.59 | Recognition of personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. othersCC: Evaluation on the aspect of letters | There are no differences between groups in referential thinking |

| Jimenez et al.58 | Recognition of personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. social evaluationCC: Evaluation on the aspect of letters | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ RT when doing self-references |

| Larivière et al.56 | Reference on phrases | RC: Self vs. others | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ Self-references |

| Girard et al.57 | Reference on phrases | RC: Self vs. othersCC: Emotional valence of the phrase | There are no differences between groups in referential thinking |

| Lee et al.54 | Reference on faces and personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. famous person vs. unknown person | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ Negative self-references related with own face and non-familiar faces |

| Pankow et al.53 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. Angela MerkelCC: Evaluation on the aspect of letters | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ Aberrant salience |

| Liu et al.48 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. familiar vs. EE.UU's former president. CC: Lexical evaluation | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ RT in positive adjectives; ↑ Negative self and other-references |

| Zhao et al.49 | Recognition of personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. othersCC: Evaluation on the aspect of letters | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ RT in all conditions;↓ Adjective recognition |

| Schneider et al.37 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. best friend vs. Harry PotterCC: Emotional valence assessment | There are no differences between groups in referential thinking |

| Shad et al.45 | Reference on dialogs | RC: Self vs. others | There are no differences between groups in referential thinking |

| van Buuren et al.36 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. Netherlands’ presidentCC: Desirability of the adjective | There are no differences between groups in referential thinking |

| Modinos et al.35 | Reference on phrases | RC: Self vs. othersCC: Evaluation of the meaning of sentences | There are no differences between groups in referential thinking |

| Park et al.44 | Reference on dialogs | They evaluate referentiality, intentionality, and anxiety | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ Self-references |

| Silva et al.41 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. familiar person or friend | Not reported |

| Fuentes-Claramonte et al.61 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. familiar personCC: General knowledge assessment | Not reported |

| Furuichi et al.60 | Reference on phrases | RC: Self vs. friendCC: Simple instruction | ↑ RT when doing self-references in both groups |

| Damme et al.38 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. BeyoncéCC: Spelling of words | HRMS>Control: ↑ Negative self-references;↓ Positive self-references |

| Zhang et al.55 | Reference on phrases | RC: Self vs. familiar personCC: General knowledge assessment | Not reported |

| Ćurčić‐Blake et al.50 | Reference on phrases | RC: Self vs. persona cercanaCC: General knowledge assessment | Not reported |

| Tan et al.51 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. China's former presidentCC: Emotional valence assessment | Schizophrenia>Control: ↓ RT when doing positive self-references |

| Zhang et al.52 | Reference on phrases | RC: Self vs. persona cercanaCC: General knowledge assessment | Schizophrenia>Control: ↓ Positive self-references ↑ Negative self-references |

| Pauly et al.47 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. persona cercanaCC: "r" letter lexical search in the word | Schizophrenia>Control: ↓ RT in generalThere are no differences between groups in referential thinking |

| van Der Meer et al.46 | Reference on phrases | RC: Self vs. othersCC: General knowledge assessment | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ RT in general |

| Holt et al.43 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. close personCC: Desirability and perception of the adjective | There are no differences between groups in referential thinking |

| Murphy et al.42 | Reference about personality adjectives | RC: Self vs. familiar person or friendCC: Emotional valence assessment | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ RT in general |

Abbreviations: ↑, increased; ↓, decreased; CC, control condition; HRMS, high-risk mental state; RC, referential condition; RT, reaction time; Self, self-referential evaluation.

There was more consensus regarding the specific technique used, with twenty-six out of the twenty-eight reviewed studies (92.86 %) asking participants to decide whether adjectives were applicable to themselves (self-referential condition, "represents me") or to other people (other-referential condition, "represents another person"). Additionally, a large number of studies included a control condition in which participants had to perform various tasks (80.77 %), such as a lexical evaluation,38,47-49,53,58-60 a semantic evaluation,35,46,50,52,55,61 or an emotional evaluation of the desirability of words.36,37,40,42,43,57

As for the results, some studies did not find significant differences between patients and control subjects.35-37,40,43,45,57 Other studies found differences in reaction time (28.57 %), with the usual trend being that the patient group had a longer latency of response when making self-references.39,42,46,48,49,58 Regarding the number of self-references, the patient group made a higher number of self-references to negative stimuli (21.42 %) and a lower number of self-references to positive stimuli (17.86 %).

Neural bases of referential thinkingThe evaluation of the underlying nervous system activity in the referential thinking process was mainly carried out through functional magnetic resonance imaging (85.71 %), using various techniques such as BOLD (Blood-Oxygen-Level Dependent) or VBM (Voxel-Brain Morphometry). Additionally, three studies used electroencephalography41,49,59 and one of them used structural magnetic resonance imaging in combination with functional imaging.62

At the intragroup level, both groups showed hyperactivation in areas such as the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) (19.71 %) and the precuneus (17.86 %) during referential thinking. Specifically, the control group had hyperactivation of areas such as the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC) (57.14 %), the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) (21.43 %), the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) (29.57 %) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (14.28 %). Among the patients, hyperactivation of the dmPFC (39.28 %), PCC (31.14 %), and vmPFC (17.86 %) was observed when analyzing the neural activity related to this process.

When comparing both groups, greater differences were found. Thus, when comparing the patient group with the controls, hyperactivation was found in diverse structures such as the precuneus (17.86 %), ACC (17.86 %), PCC (14.29 %), insula (14.29 %), dmPFC (10.71 %), and vmPFC (10.71 %). Analysis at the electroencephalographic level showed a reduction in the amplitudes of the P2, N2, and P3 waves in the patient group compared to the controls.

Table 4 shows a detailed analysis of the results of the evaluation of the neural bases of referential thinking in each of the selected articles.

Nervous system: evaluation and results of selected studies.

| Study | Technique | Intragroup results | Intergroups results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collin et al.40 | fMRI | HRMS: ↑ Precuneus & PCC related to referential thinking | HRMS>Control: ↑ Precuneus [RH] & PCC [RH]↑ Cerebelo & oTC inferior |

| Raju et al.62 | fMRI | ↑↓ Frontal pole [RH] in both groups | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ Frontal pole volume [LH] when doing referential thinking |

| Park et al.39 | fMRI | Control: ↑ LG [RH] when 3rd > 1st personHRMS: ↑ LG, sOG, mOG, mFG when 3rd > 1st person | HRMS>Control: ↑ Precuneus & mOG when doing referential thinking [3rd person]Control> HRMS: ↑ vmPFC & mOFC when doing referential thinking |

| Jia et al.59 | EEG | ↑↓ Theta and beta bands in both groups | Schizophrenia>Control: Abnormalities in alpha rhythm during referential thinking [100-300ms] |

| Jimenez et al.58 | fMRI | Control: ↑ mPFC & vmPFC when self > other-referencesSchizophrenia: ↑ PCC, precuneus & TPJ when self > other-references | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ Precuneus when doing referential thinking |

| Larivière et al.56 | fMRI | ↓ PCC & precuneus in both groups↑ ACC & anterior insula in both groups | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ ACC, mPFC, OFC & anterior insula when doing referential thinking |

| Girard et al.57 | fMRI | ↑ Frontal regions in both groups | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ ACC, insula, precuneus & caudate nucleus related to emotional valence of referential thinking |

| Lee et al.54 | fMRI | ↑ dmPFC, vmPFC, insula & PCC in both groups | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ Precuneus & ACC when doing referential thinking |

| Pankow et al.53 | fMRI | ↑ CMS [ACC, insula, cerebellum & vmPFC] related to referential thinking in both groups | Schizophrenia>Control: ↓ vmPFC when doing referential thinking |

| Liu et al.48 | fMRI | ↑ mPFC, IFG [LH] & insula in both groups | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ GPL [RH], PCC & ↓ Precuneus, POG & IFG [LH] when doing referential thinking |

| Zhao et al.49 | EEG | Schizophrenia: ↓ Positive slow wave | Schizophrenia>Control: Lower P2 amplitude; different N2 amplitude in self > other-referential conditions; correlation between referential thinking and P3 in parietal cortex |

| Schneider et al.37 | fMRI | Control: ↑ ACC & mPFC related to referential thinkingHRMS: ↑ LG & cerebellum [LH] related to referential thinking | Control>HRMS: ↑ ACC [LH], sFG [LH] & caudate nucleus [LH] when doing referential thinking |

| Shad et al.45 | fMRI | ↑ Precuneus related to referential thinking in both groups | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ Post-central gyrus, inferior parietal lobe, SPG, LG, cuneus, precuneus, cerebellum & PCC when doing referential thinking |

| van Buuren et al.36 | fMRI | ↑ mPFC related to referential thinking in both groupsControl: ↑ STG related to referential thinking | HRMS>Control: ↓ mPFC-Precuneus connectivity when doing referential thinking |

| Modinos et al.35 | fMRI | ↑ CMS [mPFC, vmPFC, ACC y PCC] & insula related to referential thinking in both groups | HRMS>Control: ↑ Ínsula [LH], dmPFC [RH] & vmPFC [LH] when doing positive self-references; ↑ Ínsula, ACC & dmPFC when doing negative self-references |

| Park et al.44 | fMRI | Control: ↑ PT [RH], STG & VS related to referential thinkingSchizophrenia: ↑ PT [RH], GTI & VS related to referential thinking | Schizophrenia>Control: ↓ STG, mPFC & ↑ vmPFC when doing referential thinking |

| Silva et al.41 | EEG | ↑↓ Voltage in parieto-occipital electrodes in both groups | Schizophrenia>Control: ↓ Voltage in frontomedial electrodes during referential thinking [180-230 ms] |

| Fuentes-Claramonte et al.61 | fMRI | ↑ mPFC, PCC, precuneus, AG [LH], TPJ, mTC & CV related to referential thinking in both groups | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ dlPFC [LH] & mFG when doing referential thinking; ↓ Precuneus, ↑ dlPFC y PG when doing other-references |

| Furuichi et al.60 | fMRI | ↑ mPFC, dlPFC, IFG, TC & precuneus related to referential thinking in both groups | Control>Schizophrenia: ↑ PCC & hippocampus [LH] during referential thinkingSchizophrenia>Control: ↑ sFG [RH] & SPG [RH] during referential thinking |

| Damme et al.38 | fMRI | ↑ PCC y mPFC related to referential thinking in both groups | HRMS>Control: ↓ Coactivation between PCC & mPFC [RH] |

| Zhang et al.55 | fMRI | Control: ↑ vmPFC-caudate nucleus connectivity related to referential thinking | Schizophrenia>Control: ↓ Insula-precuneus-PCC connectivity during referential thinking |

| Ćurčić‐Blake et al.50 | fMRI | ↑ vmPFC-PCC/dmPFC connectivity in both groups | Schizophrenia>Control: ↑ PCC-vmPFC connectivity during referential thinking |

| Tan et al.51 | fMRI | Control: ↑ mPFC, PCC & ↓ cerebellum related to referential thinkingSchizophrenia: ↓ Post-central gyrus related to referential thinking | Schizophrenia>Control: ↓ dmPFC & ACC when doing referential thinking; ↑ PCC, precuneus, FG & LG during other-references > semantic condition |

| Zhang et al.52 | fMRI | Control: ↑ vmPFC, dmPFC, ACC, PCC, precuneus, AG, SPG, iSPL, cerebellum, sSPL & PG related to referential thinking | Control>Schizophrenia: ↑ PCC & precuneus during referential thinking |

| Pauly et al.47 | fMRI | Control: ↑ mPFC, OFC, GT, PTs & precuneusSchizophrenia: ↑ mPFC [LH], iOFC [LH], LG [LH] & PCC | Schizophrenia.>Control: ↓ IG [LH] during self-references; ↓ temporal poles & anterior insula [RH] during other-references |

| van Der Meer et al.46 | fMRI | ↑ PCC, precuneus, vmPFC, dmPFC, STG, insula & IFG related to referential thinking in both groups | Schizophrenia.>Control: ↓ PCC during referential thinking |

| Holt et al.43 | fMRI | ↑ mPFC & RSC related to referential thinking in both groups | Schizophrenia.>Control: ↑ PCC during referential thinking |

| Murphy et al.42 | fMRI | ↑ mPFC y PCC related to referential thinking in both groups | Schizophrenia.>Control: ↓ FG [RH] & STG when doing other-references |

Abbreviations: ↑, increased activity/more; ↓, decreased activity/less; ↑↓, same activity/equal; >, compared to; AG, angular gyrus; CC [A- and P-], anterior and posterior cingulate cortex; EEG, electroencephalogram; FG [-i, -m, and -s], inferior, medial, and superior frontal gyrus; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; H [R- and L-], right and left hemisphere; HRMS, high-risk mental state; IF, inferior gyrus; LG, lingual gyrus; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; OG [-s and -m], superior and medial occipital gyrus; PFC [DL-, DM-, M-, and VM-], dorsolateral, dorsomedial, medial, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex; PG, prefrontal gyrus; POG, parieto-occipital gyrus; RSC, retrospenial cortex; SPG, supramarginal gyrus; SPL [i- and s-], inferior and superior parietal lobe; STG, superior temporal gyrus; STP, superior temporal pole; TC [m- and o-], medial and occipital temporal cortex; TPJ, temporo-parietal junction.

The assessment of methodological quality of the included articles showed a low risk of general bias (Supplementary Material 4), with an average score of 6.46 stars (SD = 0.92; range 4-8). Specifically, in the selection of participants and comparability between groups, most studies presented a low risk of bias, with a higher risk observed in the category that evaluated the exposure of subjects to experimental tasks assessing referential thinking.

DiscussionReferential thinking has been a widely studied process in individuals within the psychotic spectrum, being related to other processes such as aberrant salience or identity fragmentation. Specifically, identity and referential thinking have an irreplaceable connection, with the latter representing an interference to the continuity of the self.63 Despite the importance of these concepts in the pathological domain, they have progressively disappeared from the psychopathological vocabulary,64 contrasting with the upward trend observed in the decadal evolution of published records, which would indicate a separation between the scientific and applied fields.65

The forms of referential thinking assessment have been diverse, with the classic task of determining whether a personality adjective refers to oneself (self-reference) or to others (other-reference)66,67 being among the most prominent. Other forms of evaluation of this process include the evaluation of sentences or videos with dialogues where personality adjectives are inserted. A possible connecting element among all these forms of assessment would be that stimuli have to refer to personality characteristics. That is, the stimuli used have to have a minimum referential content (e.g., using personality adjectives) that allows the self-referential process to initiate.22

Senín-Calderón et al.15 previously noted that referential thinking is a common cognitive process. This is consistent with the findings of the included studies, which show that healthy individuals make the same number of ideas of reference as patients. However, a more detailed analysis reveals that patients make more ideas of reference to negative stimuli and fewer to positive stimuli, as well as having a longer response latency when performing referential thinking. Both factors have been shown to be indicators of greater stability in the process,19,23 confirming that longer response latency and more negative ideas of reference could be markers of crystallization or progression in the psychotic spectrum.

In the field of cognitive neuroscience, very diverse results have also been found. Thus, at the neurobiological level, both patients and healthy subjects showed increased activity during referential thinking in areas such as the inferior frontal gyrus, the precuneus, and the cerebellum. Specifically, patients showed hyperactivation of the precuneus, the anterior (ACC) and posterior (PCC) cingulate cortices, the insula, and the dorsomedial (dmPFC) and ventromedial (vmPFC) prefrontal cortices.

The set of areas related to this process coincides with the model of medial cortical structures,20 to which dysfunction in other areas that had previously been highlighted in the scientific literature in relation to referential thinking, such as the temporo-parietal junction29 or the insula,26 have been added. The way in which this varied set of areas is integrated could be given by van der Meer et al.'s68 model of functional connectivity of referential thinking. In this sequential model, the ACC would direct attention to the stimulus; the vmPFC would perform a self-evaluative assessment; the PCC would activate autobiographical memory; the insula would perform the reference; and, finally, the dmPFC would make the decision about whether the stimulus is applicable to oneself.69 A reinterpretation of this model for the spectrum of schizophrenia and HRMS, integrating the findings observed in reviewed studies, can be observed in Fig. 5. Taking into account that dysfunction has been reported in almost all of the areas that make up the model in this review, it would not be surprising if dysfunction in these connectivity hubs were behind the deficit in this process. However, this model was designed to explain the correct functioning of referential thinking, so its extrapolation to explain the pathological functioning of this process should be taken with caution.

Integrated model of postero-anterior functional connectivity hubs underlying referential thinking in schizophrenia spectrum disorders and HRMS.

Notes: 1. Representation based on an expanded reinterpretation of the self-reflection model proposed by van der Meer et al.68 for healthy population. 2. The numbers indicated in each area (e.g., x14 in dmPFC) refer to the number of reviewed studies reporting hyperactivity in that structure. 3. Abbreviations: ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; dmPFC, dorso-medial prefrontal cortex; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; vmPFC, ventro-medial prefrontal cortex.

It is relevant to discuss the implications of the hyperactivation of this hub of structures in referential thinking. On the one hand, the consistent involvement of the same set of brain regions in identity processes might have an evolutionary value, with a higher concentration of areas in the prefrontal regions, which were among the last to develop in the human brain,70,71 concurrently with the emergence of higher-order processes such as insight, self-perception, and identity.72,73 Probably, as these processes extended to external stimuli, functional connectivity networks connecting these prefrontal areas with other sensory areas may have consolidated, as proposed in van der Meer's model of normal referential thinking.68

However, in the context of referential thinking as observed in individuals with high-risk mental states and schizophrenia spectrum disorders, it is crucial to investigate the clinical and experiential implications of the hyperactivation of these set of areas. Specifically, this marked hyperactivity could indicate two things: 1) a greater difficulty for these patients in disengaging from self-referential thinking, continuously dwelling on these thoughts without being able to separate from them normally; and 2) a greater number of self-referential thoughts throughout the day (increased frequency), particularly involving negative valence stimuli (more negative self-references), which could indicate progression along the continuum. Therefore, clinically, the hyperactivation of these areas would imply excessive concern about self-references, persistently present in the patient's discourse (greater stability).

Additionally, the highlighted node of brain structures resembles the default mode network (DMN), which is composed of the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and the precuneus, among others.74 Hyperactivation of this network has been proposed in relation to referential thinking in people with major depressive disorder, where they were unable to inhibit the network activity when making ideas of reference to negative stimuli.75 Similar findings have been observed in patients with schizophrenia, where aberrant DMN activity has been related to cognitive interference during referential thinking,43 as well as in individuals with high-risk mental state (HRMS), where there is hyperactivation of the posterior DMN (precuneus and PCC) during this process.76 Thus, hyperactivation of this network could also underlie referential thinking problems in the psychotic spectrum.

When comparing individuals in the schizophrenia spectrum with those presenting HRMS, some notable differences are found. For example, at the referential thinking level, subjects with HRMS have fewer differences with the control group than those with schizophrenia, where there is a clear deficit compared to healthy subjects. This supports the proposal that referential thinking serves as a marker of progression in the psychotic continuum, with greater stability of this process as the disease progresses.15 At the neurobiological level, hyperactivation and connectivity failures are notable in the PCC, precuneus, and mPFC (corresponding to the posterior DMN cluster) in the HRMS group.38,39,40 Therefore, this cluster could be related to the progression of this prodromal symptom towards psychosis, as indicated by Collin et al.76.

In addition to referential thinking, there are many other mental processes equally related to the processing of the self and identity, such as causal attributions, ideas of reference, all-or-nothing thinking, labeling, or arbitrary inference, among others. Although there may be subtle differences between these processes, mainly regarding the intentionality of the referent or the object of reference, they all share the need for some type of self-referential processing, involving very similar brain areas (e.g., causality attributions77,78; ideas of reference79; all-or-nothing thinking80; labeling81,82; arbitrary inference83,84). Thus, insofar as any of these cognitive processes engage in self-referential processing, similar brain areas to those highlighted in this review will be recruited, particularly the activity of midline cortical structures such as the medial prefrontal cortex,85,86 the posterior cingulate cortex,87,88 or the temporoparietal junction (TPJ).89,90

In this way, to the extent that this entire set of mental processes shares a connection in terms of self-processing, they also share a pattern of brain connectivity. However, with the available data, we cannot assert that all these self-referential processes are identical on a functional brain scale; rather, they will recruit the activity of similar brain areas as their function is similar. Thus, according to van der Meer's functional connectivity model of referential thinking, different areas will be recruited in self-referential processing depending on the sub-process required to carry out each of these self-related mental processes.68

Lastly, one aspect worth discussing is why, at the onset of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, ideas of reference become stable and intense. One possible explanation for this was proposed by Senín-Calderón et al.,91 who suggest that a cognitive process present and functioning well in healthy individuals allows them to dismiss or mitigate the presence of ideas of reference, disengaging from self-referential processing and consequently alleviating its emotional impact.92 Patients on the psychotic spectrum lack these resources and are more vulnerable when referential thinking emerges, making it more difficult for them to disengage from self-referential processing. This absence of resources may be due to a prior state of chronic mental and physical fatigue93 and the presence of moderating variables of this process, such as aberrant salience22,93). Aberrant salience assigns excessive significance and salience to otherwise neutral stimuli,94 making these individuals more sensitive to external stimuli, leading to erroneous interpretations and consequently a greater stabilization of IRs,93 experiencing these ideas with aversive and alarming significance. Specifically, once stabilized, aberrant stimulus salience would feed back into these ideas of reference, making them less aligned with reality.95 This whole set of experiences would consequently increase negative affect and hypervigilance, leading to a greater number of ideas of reference as individuals become highly attentive to the surrounding context, thus entering a cycle in which these ideas stabilize and eventually become delusions of reference in some types of disorders within the schizophrenia spectrum.79

At the brain level, the process that allows for the analysis of the veracity or relevance of self-references could be of cortical origin, while their activation or emotional alarm might be related to more temperamental factors associated with neurobiological networks closer to the limbic system, related to sensitivity to punishment and reward.93,96 The salience of certain social stimuli (e.g., a glance, a whisper) makes it easier for them to capture our attention and become significant. This increased aberrant salience of various stimuli has been linked to subcortical dysregulation of the dopaminergic system,68 given that brain regions more related to the limbic system (medial cortical structures) have strong connections with the limbic system and the striatal dopaminergic system. Thus, aberrant salience would contribute to a greater stabilization of IRs, making them less aligned with reality while also increasing their frequency by enhancing the salience of multiple stimuli.95

In this model, the dysfunctional connection between the ventral striatum, the limbic system, and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex leads to the attribution of salience and self-references in a hyper-reflective sense.97 Consequently, there would be abnormal functioning of the default mode network and an inability to suppress its activity, affecting task resolution among individuals with psychosis, resulting in a significant increase of ideas of reference, experienced as stable and alarming.98 Nevertheless, due to the possible dopaminergic involvement when aberrant salience participates in this framework, this model may be more suitable for the onset of “hyperdopaminergic” psychosis, but not for the “normodopaminergic” variant, which is more closely associated with dysregulations of the glutamatergic system.99 Therefore, more research is needed in this regard for the latter type, which has received less attention in the literature over time.

Limitations and future perspectivesThe main limitation of this systematic review is that the included studies had heterogeneity in their experimental procedures and designs, which prevented a quantitative review of the studies. Additionally, the included studies did not report effect size or statistical power indices, which affects the validity of statistical conclusion. Some relevant confounding variables in the early development of psychosis,100 such as years of education or employment status, were not controlled in any of the reviewed studies. It is recommended that future studies use systematic evaluations of referential thinking, reporting key statistical values (such as effect size) and conducting a comprehensive control of confounding variables. This would allow for a long-term meta-analysis of the neural bases of prodromal symptoms such as the one presented here. Additionally, it would be interesting for future research to use longitudinal designs to evaluate subjects from premorbid stages in order to detect both biological and behavioral markers of progression that can improve prevention and intervention programs. Such designs may be necessary to study the transition from ideas of reference (common, attenuated and transient) to delusional ideas of reference (stable and unshared).101

Another significant limitation of this review is that all included studies, due to their experimental focus on referential thinking, use tasks where visual processing is highly relevant (e.g., "read this adjective or this sentence containing a personality adjective" or "look at this scene where referential stimuli appear"). Due to this exclusively visual processing, the precuneus might emerge as a relevant structure precisely because of this higher-order sensory processing. Future studies should test other ways of activating referential thinking (e.g., "think about the last time you saw someone on the street and thought they were whispering about you") to elucidate whether the precuneus is relevant in the model solely for its role in sensory processing or also due to its fronto-parieto-occipital connections.

ConclusionsThis systematic review has allowed us to observe the different functional networks related to the deficit in referential thinking both in the schizophrenia spectrum and in high-risk mental states. The presented results confirm the role of referential thinking as an indicator of progression in the psychotic continuum, with longer latency of the process and a higher number of negative self-references being common among patients. Additionally, hyperactivation of midline cortical areas, such as the dorsomedial and ventromedial prefrontal cortices, anterior and posterior cingulate cortices, and precuneus, has been identified in relation to the deficit in referential thinking. The main finding of this review, we believe, lies in the identification of the set of areas underlying this process and their integration into a functional model. It is expected that the gathered evidence will improve early detection and intervention and promote research on both biological and behavioral markers in psychosis.

Ethical considerationsNon applicable.

FundingDSC is funded by a predoctoral fellowship for University Teacher Training [“Formación del Profesorado Universitario”] from the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades of Spain [PhD grant ref. FPU21/00344].

CRediT authorship contribution statementDaniel Santos-Carrasco: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Juan Francisco Rodríguez-Testal: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Manuel Vázquez-Marrufo: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Graphical abstract and Fig. 5 created with BioRender.com. Figs. 3-4 created with VosViewer. We would like to thank Sergio Villa-Consuegra for his assistance during the article selection and screening process.