We conducted a systematic review to determine which psychological assessment measures are most commonly used by emergency services to assess the psychological response of the general population in a crisis event and the time point at which the assessment is carried out.

MethodA systematic review was performed based on PRISMA recommendations and registered with PROSPERO by searching in electronic citation databases (Web of Science, PubMed, and PsycInfo).

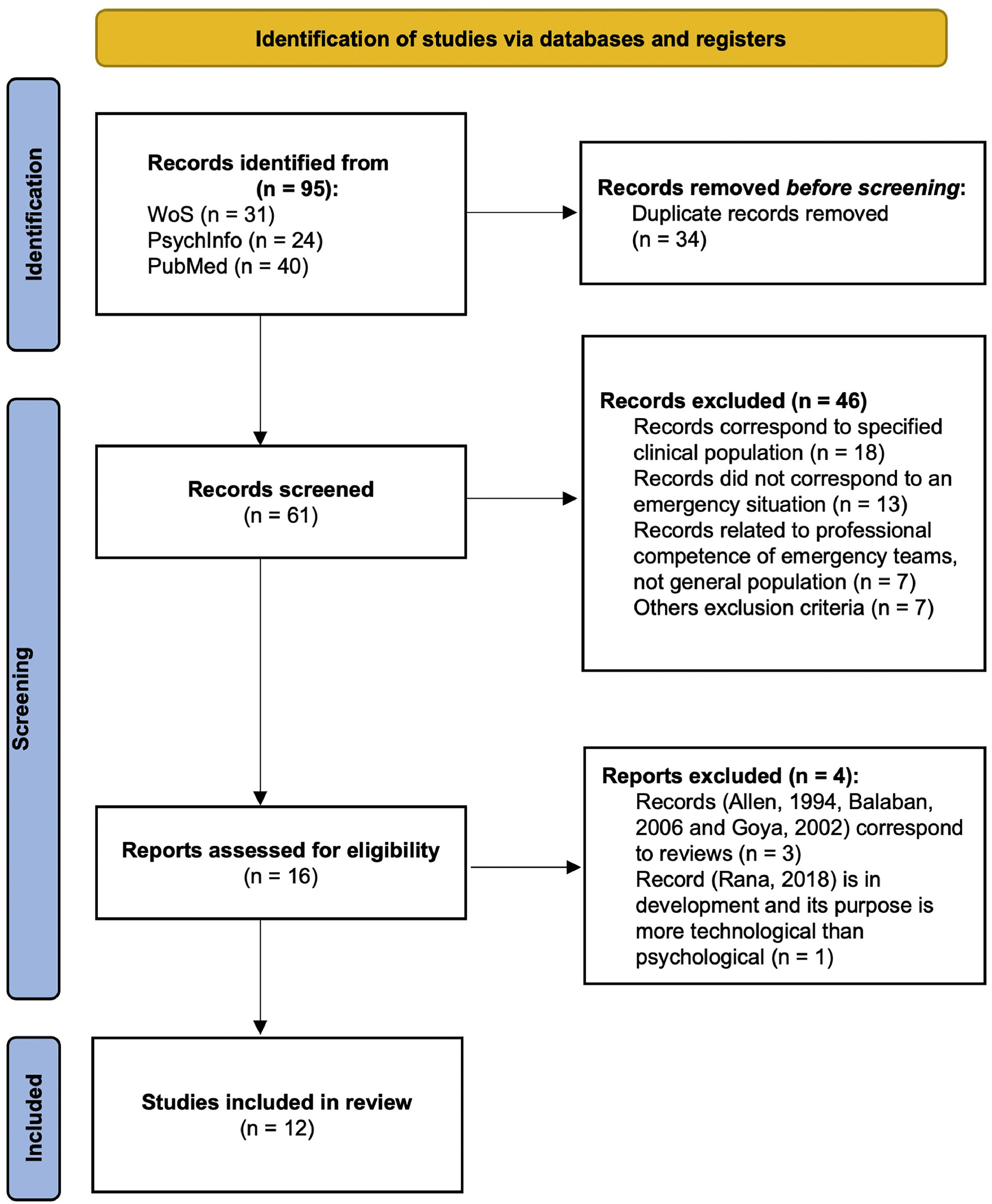

ResultsTwelve studies were included. The flowchart shows the entire decision-making process. Among the variables assessed, self-report measures that assess PTSD stand out above all others, followed by self-report measures that assess negative emotional states (anxiety and depression). Psychologists frequently appeared among the professionals involved in the assessments. None of the experiences analyzed were an assessment carried out immediately after the event.

ConclusionVery few psychological assessment instruments have been developed in the context of emergencies, and those that are used are translations of others designed in a clinical context. According to the latest research, studies tend to overlook the importance of the time elapsed between the event and assessment.

Psychological care in crises, emergencies, and disasters is increasingly being formalized through protocols, and there are more services offering integrated care that also addresses psychological and emotional needs. In this regard, psychology in the field of emergencies has gained recognition and expansion in recent years.1

As in any emergency, time is a crucial factor. The objective is to assess and treat any injury that poses a life-threatening risk to a person as quickly as possible. This risk can be both physical and psychological, and prioritizing its attention is crucial in any case, as the chances of recovery and/or prevention decrease significantly as time elapses from the accident/incident.2–4

Despite the importance placed on the above aspects, few instruments allow for the assessment of individuals' initial psychological responses to crises, emergencies, and disasters. This initial psychological response has unique characteristics that distinguish it from subsequent responses, and can be the subject of study and attention in psychology. It is often a stress response to serious events, known as the Acute Stress Response (ASR),5 also known as the Survival Response.6 The Acute Stress Response is considered a normal and adaptive reaction. Despite its variability in response, both within the same person (encompassing responses in all spheres of human behavior: physiological, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral)7 and among different individuals (distinct response patterns and profiles), as well as the potential intensity of its manifestations, it is not considered pathological. Instead, it represents a person's coping attempts in the face of the severe event they are experiencing at that moment.

Beyond this initial Acute Stress Response, the impact of disasters on the general population and the psychological problems that can arise for victims have received much attention.8,9 However, studies have mainly focused on understanding the psychological impact on victims after the event rather than investigating their responses in the first hours, which could provide valuable information regarding the evaluation needs of professionals and the implementation of psychological interventions tailored to the needs of individuals affected by such serious incidents.10

The growing presence of psychological professionals in the field of emergencies should be supported by assessment and intervention protocols and methods to facilitate their work and decision making. These protocols must be quick to apply and easy to integrate into the routine assessment procedures. They should also be sensitive to the entire continuum of peopleʼs stress responses, not only to the presence of psychopathology. This differentiation sets them apart from other instruments, such as those aimed at psychiatric assessment in emergencies and/or those assessing post-traumatic risk in the months following an incident/accident.

To achieve this, we conducted a systematic review with the following objectives:1: identifying the most frequently used psychological assessment measures by emergency services and the variables they assess2; determining which professionals apply these measures3; understanding the setting or type of events for which the assessment is carried out; and4 considering the time elapsed since the incident or emergency and the timing of assessment.

MethodsThe systematic review protocol was registered in PROSPERO after checking the database for similar review purposes (CRD42021279963). Articles were selected and chosen for inclusion in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.11

The question that this review aims to answer is twofold. On the one hand, to identify the psychological assessment tools and instruments in emergency, crisis, or disaster situations applicable to the population in general. And on the other hand, to determine at what point in time after the incident they are applied.

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studiesThe following research filters were applied as inclusion criteria: papers, book chapters or thesis dissertations had to be written in English or Spanish and published from the beginning of time until September 27, 2023. Other inclusion criteria were as follows: a) participants of any age; b) who had been assessed after a crisis, emergency, or disaster; and c) who were assessed with a protocol and/or assessment instrument. The exclusion criteria were as follows: a) people not directly linked to stressful or traumatic events such as family, friends, etc.; b) psychiatric population or studies on samples with previously defined disorders; c) reviews and meta-analyses; and d) reports such as magazine, abstract only or letter.

Literature searchWe conducted a computerized search of the Web of Science (WoS), PubMed, and PsycInfo databases. The literature search was conducted using a Boolean algorithm with the following keywords: (EMERGENCY OR CRISIS OR DISASTER) in the abstract, (“PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT”) in the abstract, and (INSTRUMENTS OR TOOLS OR MEASURES OR QUESTIONNAIRES OR SCALES) in any part of the paper.

Study selection processThe previous literature search was independently conducted by two researchers (authors of the present study), resulting in a 100 % agreement rate between them regarding the search. All papers identified by the two researchers were included in the study.

According to the search criteria, studies meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were selected on their abstracts. Two reviewers classified papers as either related or unrelated to the study. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. Papers deemed related to the study were further evaluated for eligibility based on their full text, and decisions were made regarding their final inclusion in the review.

Data extraction processes for each studyThe full text of selected papers was thoroughly examined for data extraction using an assessment form addressing the following categories: sample characteristics; setting/situation (in emergency service or not); time point of assessment (e.g., first hours, months, unspecified); details of the measures employed (e.g., variable assessed, number of items, application information such as interview, professional protocol, or self-report); and the professional responsible for the assessment. Additionally, any significant comments made by the authors were noted. This data extraction process was also carried out independently by the two researchers, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and the establishment of a consensus.

Method of analysis and synthesis of informationThe analysis and assessment of information followed a qualitative or narrative synthesis approach. In this regard, the results of the systematic review were synthesized into: psychological assessment measures utilized, professionals administering these measures, settings or contexts of assessment, and timeframe elapsed after the incident when the assessment took place.

Quality of included studiesSelected studies were assessed using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS;12), tailored to the specific content of this systematic review (see Supplementary Table S1). Therefore, criteria such as sample representativeness, sample size, non-participants, assessment of psychological response after crisis, emergency, or disaster, and the quality of reporting descriptive statistics were evaluated. The quality assessment process was independently conducted by the authors for all studies. Any disparities were addressed though discussion to reach a consensus. A risk of bias analysis was conducted for each study.

ResultsA total of 12 studies comprises this systematic review.13–24 Following the specified search criteria, we identified a total of 95 records (31 in WoS, 24 in PsycInfo, and 40 in PubMed). After duplicates were removed, a total of 61 papers were screened by reading the abstract. Subsequently, 16 papers were chosen. Three of these were later discarded; thus, thirteen articles were fully reviewed and were included. Fig. 1 presents a flowchart summarizing the search and selection process.

The main characteristics of the selected studies are presented in Table 1. The paper by Conn13 is a PhD thesis and the reference by Olden et al.14 is a book chapter, both of which were included in the selected studies, taking into account their relevance for being carried out in an emergency context.

Sample description of the analyzed papers.

Note: Not specify (NOS), Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD.

Regarding the quality assessment of the included studies, two studies15,16 were considered at high risk of bias (<3 points). However, as these are two studies that present two assessment measures, they have been kept in the review for two reasons. First, it fits perfectly with the purpose of this systematic review, and second, because of the importance of conducting systematic reviews on psychological assessment.25

Psychological assessment measuresFrom the analysis of the assessment measures administered in the twelve investigations, we would highlight the following results:

1. Regarding the variables assessed, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) stands out above all others. In all studies in which the sample was made up of humans, PTSD was always assessed; logically, the studies in which institutions15 or programs16 were assessed.

The second most assessed variable is negative emotional states (anxiety and depression) that focus five of the twelve works.14,17–20 In two research papers, a general psychopathology assessment scale that functions as a screening tool was applied.14,21 In the work in which the sample was made up of children, a list of symptoms adapted to this age range was used.21 Finally, in only one study was the following variables jointly assessed: alcohol use and abuse, psychophysiological arousal, general functioning, and perceived social support.18

It must be remembered that the two studies included in this review go beyond the general trend. Meredith et al.15 assessed the levels of hospital preparation to respond to this type of situation with an ad hoc protocol, and Conn13 analyzed a nursing clinical record review protocol to evaluate its usefulness in case referrals.

2. In relation to the instruments applied, the use of several instruments is frequent in studies, even to assess the same variable (PTSD, for example), so there is no correspondence between the frequency of the measure and the range of studies. Thus, the data were raw data on the use of the instrument.

As expected, the largest number of measures corresponds to those that assess PTSD, the most common of which is the 22-item Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES),26 which was used in six research papers (46.15 % of the total). Thus, the model that underlies this scale is clearly adopted by most researchers to consider the presence of post-traumatic psychopathology. The other ten measures that assess this psychopathology are all different, including four for children and six for adults (see Table 1).

Regarding the assessment of anxiety, seven measures were applied: four for children (see Table 1) and three for adults, including the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2),27 which was used in two studies. In the case of depression, five different measures were used: two for children and three for adults, with the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II),28 which was applied in two studies.

Behavior disorders were assessed only in child samples using four different measures (see Table 1); in the two studies in which general instruments were applied, two screening measures were used, as well as a semi-structured interview. The rest of the measures for four specific aspects (alcohol use and abuse, psychophysiological arousal, general functioning, and perceived social support) are shown in Table 1.

Of special interest are two works in which triage scales or protocols were used to facilitate a good referral. In the work of Brannen et al.,16 two very simple scales were developed: the Fast Mental Health Triage Tool and the Alsept-Price Mental Health Scale, which assess medical and psychological conditions and exposure to traumatic experience in order to aid the referral decision. However, the work of Conn13 is more complex, as it uses a protocol called the Triage Assessment Scale (TAS),29 with the same purpose of assisting in triage and referral in initial nursing care after a violent event.

Professionals that apply the psychological assessment instrumentsOf the twelve works selected, in two it was not specified who conducted the assessment. As can be seen in Table 1, although there was no uniformity in the professionals involved in the assessment, four of the ten which specify the professional mention a psychologist.

Setting or situations of assessmentNot only is there no unanimity regarding the type of event to which the studies are linked in the twelve selected papers, but each of them refers to a different situation. Some studies assess the psychological impact at the community level: impact of the war in high school students,21 and impact of COVID-19.17,19,20 In other studies, health professionals involved in emergency situations have been evaluated,16,19 and in another it was the centers involved as an institution.15 In both the cases, these were generic.

Two papers referred to those affected by the 9/11 attacks in New York: one focused on the victims22 and the other on the rescue personnel in the same event.14 In another study, rescue personnel from a plane crash were studied.18 The article by Fichera et al.23 refers to bank workers who had been victims of robberies and that by Hendaus et al.24 to Syrian refugees.

Finally, Conn's research13 was conducted with victims of violent crimes.

Time elapsed after the incident when the assessment is carried outIn three of twelve works reviewed, this period is not important, since Brannen et al.16 was assessed through vignettes, Conn13 using medical records, and Meredith et al.15 focused on institutions. Of the remaining ten, four of them (40 %) were not specified. In studies that explored the psychological impact of COVID-19, the assessment was carried out months after lockdown (evaluation by Romero et al.19 during the first month after the outbreak).The one that dealt with the effect on rescue teams was carried out one year after the stressful event.18 The work of Norris et al.,22 involving people affected by 9/11, looks at one month after the event, and in the research by Fichera et al.23 on bank workers who had been victims of robbery, these people were assessed between seven and 15 days after the robbery and 45 days later.

DiscussionThe purpose of this review is to analyze the different psychological assessment measures that have been applied so far in the context of emergencies, based on published studies. In light of the obtained results, the following conclusions can be drawn.

The selected studies focused their attention on the assessment of PTSD, followed far behind by the presence of negative emotions in the form of anxiety and depression, and screening for possible general psychopathology and behavioral disorders in minors. Additionally, in all these cases, a large number of different instruments for the same variable are also used in the different studies, making comparison very difficult. This finding does not fit the assessment needs in the context of emergencies, where the time factor is essential30,31; therefore, one of the priority criteria is to have assessment measures that are as brief as possible to identify and intervene in any affectation that poses a risk to the person. All the above paints a picture, in our opinion, of one of the most important difficulties in research in this field, which is the multiplicity of instruments to assess the same variable.

Another of our findings is that the studies reviewed tend not to consider the time elapsed between the event and the assessment of those involved as an important variable, and therefore do not provide details, even though the specialized literature places great importance on this period, giving rise to key concepts such as the “window of opportunity” to prevent post-traumatic symptoms.3,4,32 This is an important difference with respect to when the intervention of emergency teams is recommended. They must be able to assess the mental state of the affected people immediately after the event, if possible, in the same scenario as the event, and take full advantage of this “opportunity” to offer an intervention that fits their needs.10,33

Only one study13 used a measure aimed at assessing a personʼs mental state immediately after a potentially traumatic event, acting preventively on possible psychopathology and not assessing already established psychopathology, as practically all the consulted studies do. Nevertheless, based on the rubric it presents, the scale requires a lot of time to complete, affecting the time criterion.

Thus, it can be deduced that today, there are minimal psychological assessment procedures and instruments developed in the context of emergencies, and those that are used are usually a translation of others designed in a clinical context (post-traumatic stress or depression and anxiety measures). This means that, in their conceptualization, these instruments are not valid (the emotional reaction in the first hours can never be the object of a psychopathological diagnosis)34; therefore, they do not meet the specific needs of the field. The distinctive feature of psychological assessment in emergencies compared to other areas of psychology lies in three aspects, two of which are related: the temporal/spatial factor and the operability/brevity factor. Regarding the first, the psychological assessment must necessarily be carried out in the same place where the catastrophe/crisis is occurring, screening during the first hours (window of opportunity), whereas in other areas of psychology the focus is on the weeks and/or months prior to and at the time of the assessment. Therefore, it must necessarily be operationally brief, as the state of the people involved and the emergency for the operator administering the scale does not allow for any kind of parsimony. The third characteristic derives from the previous two, as it can be administered by any healthcare emergency and/or crisis operator attending to the person in the first instance (physicians, nurses, and emergency medical technicians). Furthermore, in other areas of psychology, there are a numerous assessment instruments with very similar objectives. However, in the field of emergencies, crises and disasters, we currently do not have effective assessment instruments to measure the acute stress response (non-pathological), and in a minimal amount of time after the critical or potentially traumatic event has occurred.

LimitationsThis systematic review has some limitations. First, this review searched only for articles in English and Spanish; other studies may have been outside this scope. Second, some relevant information was missing from many articles; for example, several studies did not specify the exact time at which the assessment occurred. Although this is already an interesting result, considering that the available research indicates the importance of assessing and intervening as soon as possible to minimize risks, the lack of information may have affected the results of the present review. Third, the sample size was predominantly small, which limits the generalizability of the results. This is particularly relevant for studies with a higher risk of bias. Fourth, in the context of crises and emergencies, the assessment can result from a complex conceptualization if a delicate and sensitive moment, such as the response in the first moments after a potentially traumatic event, is taken into consideration. Therefore, it is recommended that the assessment include self-report measures answered by the professional and not by the affected person.

Conclusions and future lines of researchOur ability to identify at-risk individual's remains very limited.35 Despite this, the first step to move forward is the development of brief detection instruments to be implemented in a short time. This would improve efforts for proper referral and follow-up, as well as provide information on what are currently intensive prevention programs. The priority in emergency services is to reduce the time required to detect possible psychological complications in a systematic way, reducing risks and favoring natural recovery (non-pathological and even less, irremediably pathological) of people in situations that may initially overwhelm them.

To our knowledge, there is currently no protocol or instrument that matches the characteristics and meets the needs presented in this review. Thus, we believe that a proposal that fills this gap and is useful is necessary for networks providing assistance to victims of violent crime and to people who have to deal with emergency situations. This future line of research would ultimately benefit the victims and the affected people themselves, which is our common and shared objective.