Social support and quality communication are crucial in suicide prevention. This systematic review aimed to identify and summarize the research on the link between these variables and suicidal behavior in adults, and their differences depending on gender.

MethodsThe Web of Science, Scopus and PsycInfo databases were searched from January 2012 to November 2022 using the terms [(suicide* OR “deliberate self-harm”* OR self- injur* OR “suicidal behavio”*) AND ("social support" OR "interpersonal relationship") AND (communication)]. Articles published in a peer-reviewed academic journal, written in English, with participants between 18 and 40 years old, assessing communication and/or social support were included.

ResultsFinally, we included 12 articles. We identified characteristics such as not perceiving social networks as a helpful resource, or difficulties in understanding the messages. Also, the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighted the role that technology played in social support for the most vulnerable people. Communication difficulties of the individual with greater risk for suicide, showed the importance of social support and seeking help.

ConclusionsThe community can contribute in suicide prevention by reducing the stigma surrounding mental illness and suicide through effective communication.

More than 700,000 people die by suicide worldwide yearly, being the 4th leading cause of death in the 15–29-year-age group in 2019.1 Specifically in the WHO European Region, 128,000 people die by suicide each year.2 Data that does not seem to vary much from the World Health Organization3 showed that 52.1 % of the global suicides in 2016 occurred among individuals under the age of 45 years. In a study assessing birth cohort-specific mortality rates in England and Scotland,4 a communality was observed in both samples at the peak age suicide-related death (30–34 years).

Risk factors for suicide are often multi-causal, with social factors like perceived social support5 and communication difficulties particularly strongly related to suicidal behaviour.6 Ju et al.7 investigated the indirect effects of communication about suicide in relationships. They obtained a positive relation between this interpersonal communication and suicide, as a behaviour to be imitated or should be performed. However, these ideas reinforce the stigma that talking about suicide is a taboo, even when the intention is to seek help.

The person must have a social network for this interaction to take place, although there is always the possibility of turning to healthcare professionals when this network does not exist or is insufficient to help them. In some cases, people can interact with strangers over internet, where the call for help may go unnoticed or be devoid of context.

Katsivarda et al.8 reviewed interventions based on communication after the first suicide attempt from 2000 to 2020 and observed good levels of effectiveness in preventing further suicide attempts. They also pointed out the need to clarify which groups of patients could benefit most.

Poor quality of communication can work to desensitize and normalize suicidal behaviours. As we can see in the study by YoungJu et al.,7 where a significant relationship was evident between communication about suicide with others, seeing it as a solution to problems and guessing others' approval. Despite this, perceived social support was a moderator.

Social isolation has been considered one of the most crucial factors to predict suicide in an individual, regardless of age, origin, or mental health.9 The moderating effects of perceived social support are evident in the association between stressful life events and depression.10 But its role as a protective factor against suicidal behaviour is not so clear.11 Angelakis & Gooding12 examined the moderating role of social support perceived in individuals both with and without a history of childhood trauma and found results in favour of its important role in preventing suicide, even when the person suffered from depression. Nevertheless, Otten et al.13 pointed out the importance of social support in preventing suicidal ideation for both women and men within prospective community cohorts, in line with the findings of Šedivy et al.14 in their study of 75 regions of 23 European countries.

With respect to gender differences, in an investigation between gender roles and interpersonal relationship style, social support and hopelessness (predictor of suicidal behaviour) showed how a positive interpersonal communication style and strong social support networks play crucial roles in preventing suicide and suicidal behaviours in both genders.15 Another study among college students concluded that social support from family was an important predictor of suicidal thoughts only in men, but not in women.16

Also, in line with gender roles, significant interactions were observed between relationship styles and social support, aligning with prior research that indicates that women actively seek more social support and commonly employ nurturing relationship styles.15

A characteristic highlighted by Joiner's Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (JITS)17 is thwarted belongingness, which would encompass the lack of perceived social support (loneliness and the absence of reciprocal relationships).18

One of the characteristics common to all suicide that Shneidman19 stands out as an interpersonal act is the communication of suicidal intent. Joiner's Interpersonal Theory of Suicide17 emphasized the importance of this interpersonal dimension, encompassing three elementary constructs for suicide: thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness and acquired capability for suicide.20 JITS hypothesized that when the need to connect with others is dissatisfied, an attempt to belong is frustrated, leading to the death wish, along with the perception of being expendable. An acquired capability for suicide is also assumed by losing the fear of death and increasing tolerance to pain through experience.20 JITS has been well-supported in different cultures and countries, including east Asian21 and western samples.22

There are a greater number of studies focused on adolescents and children, or that encompass these two groups with adults, but not so much specifically in early and middle adulthood, which makes this age range somewhat invisible. This is also an age period in which the subject's responsibilities begin to increase (completion of studies, job search, independence from parents…) and a lot of important life events happen (family, social responsibilities…). Polanco–Roman,23 in his article about suicide of young adults in the US, emphasized the misclassification of suicides in this population due to their little representation in the studies on suicide, although it increased in the last decade.

Research on suicidal behaviour in youth has been the subject of numerous systematic reviews that shed light on various aspects of this complex phenomenon. For example, Cañón & Carmona24 studied suicidal behaviour in youth across different countries, highlighting other factors associated to suicide like biopsychosocial or stressors above most associated factors such as depression or anxiety. Similarly, the review by Doty et al.25 focused on suicide preventive interventions in youth and young adults, not particularly reflected in psychological aspects even though most of the interventions addressed were directed at mental health.

Reviews on psychosocial aspects such as social support have been conducted in specific populations like the study of Fei-Hong et al.26 with severe mental illness patients, but does not make particular emphasis on specific age groups. In the context of this body of research, our systematic review seeks to expand current knowledge by specifically analysing and summarizing research into the link between social support and interpersonal communication on suicidal behaviour in young/early middle adults through a qualitative systematic review. Suicidal behaviour includes both ideation and attempts or completed suicide. By focusing on the communication of suicidal behaviour, barriers to communicating suicidal thoughts and the perception of this message and in the most specific aspects of social support, our review brings a unique perspective by identifying barriers to these protective factors of suicide and examine their manifestation in this context, as well as emphasizing potential disparities based on gender.

Furthermore, by considering the existing evidence in conjunction with the results of previous reviews, our research provides a more complete view of the landscape of suicidal behaviour. Greater knowledge of the variables involved in communication and social support in this age group will facilitate the understanding and design of more effective prevention strategies.

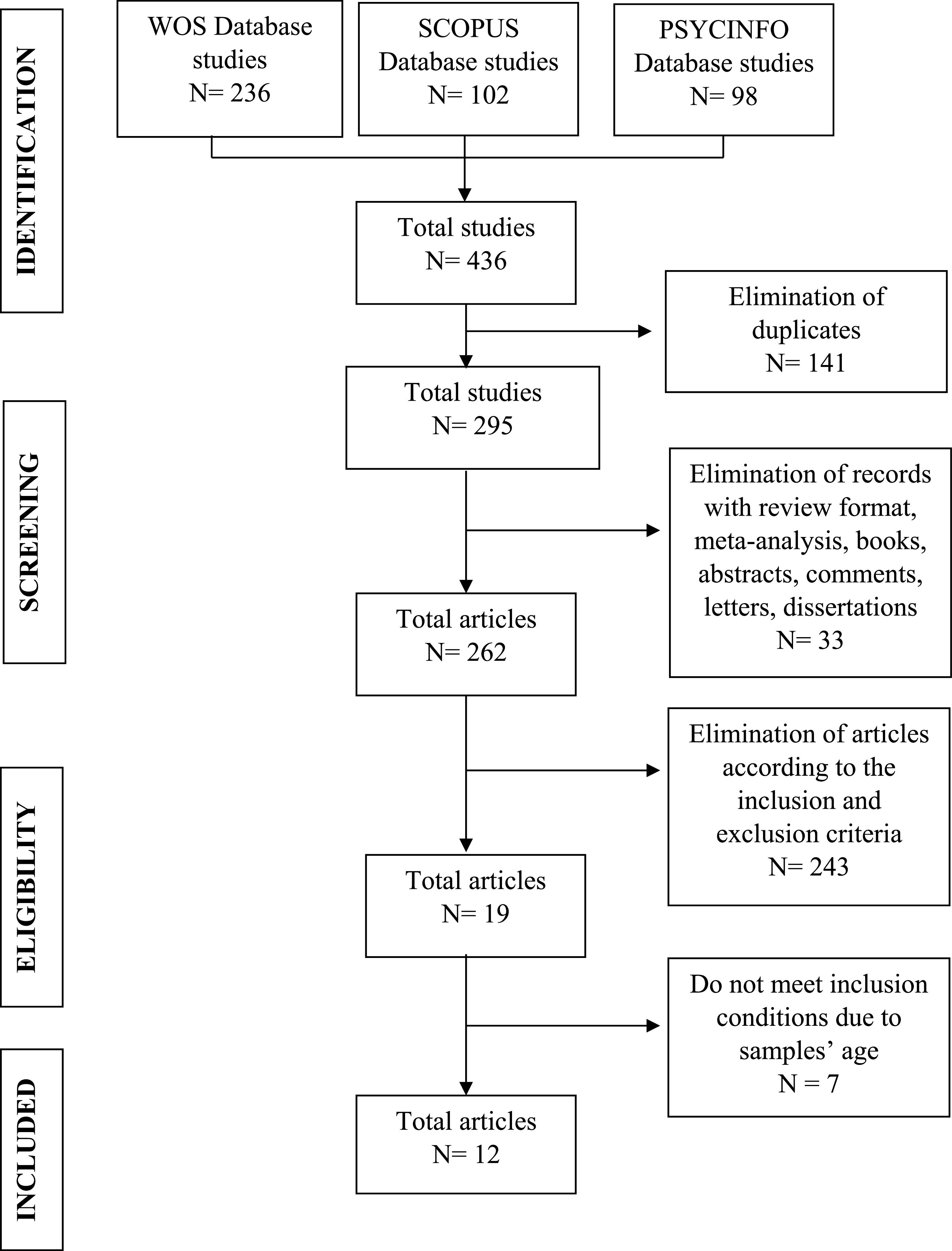

MethodsLiterature searchFor the development of this exploratory systematic review, the PRISMA verification protocol was used.27 A literature search was conducted from 5 May 2022 to 19 May 2022 and an additional search was performed from 4 November of 2022 to 30 November 2022 in the electronic databases PsycInfo, Web of Science and Scopus, using the terms: [(suicide* OR “deliberate self-harm”* OR self- injur* OR “suicidal behavio”*) AND ("social support" OR "interpersonal relationship") AND (communication)]. These databases were chosen because of the high number of publications of suicide-related articles they cover internationally. Moreover, PsycInfo includes the American Psychological Association's database. The search covered articles from January 2012 to November 2022, not only to cover a relatively recent period to obtain a number that would allow the review, but also because in 2012 a guide aimed at promoting the design of suicide prevention strategies was published by the World Health Organization.28

Data extractionThe main author of this review made the initial search independently using Mendeley Desktop, so the references of the documents were extracted from the data bases. Title and abstract screening of all papers was independently performed by authors NLM-R and PM with reference to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Finally, with the Excel tool, a coding book was used in order to sort out the characteristics of each chosen article.

Assessment of risk of bias and reporting qualityAdditionally to this rigorous search, the full-text screening process and results were independently considered for all the members of the group. In case of conflict, we together reviewed the items we disagreed on and tried to further examine which features could make them to be excluded or included. Finally reaching an agreement that resulted in the final number of items selected. For assessing the risk of bias for the studies collected, the characteristics of the samples were broken down and shown in Table 1, to consider the sizes but also how detailed their information was, that at least it had sufficient quality, and the study design was also examined, longitudinal or cross-sectional. Furthermore, the evaluation tests used to measure the main variables of the studies were also examined by two of the authors to verify their quality and to assure that there were as few non-standardized measures as possible.

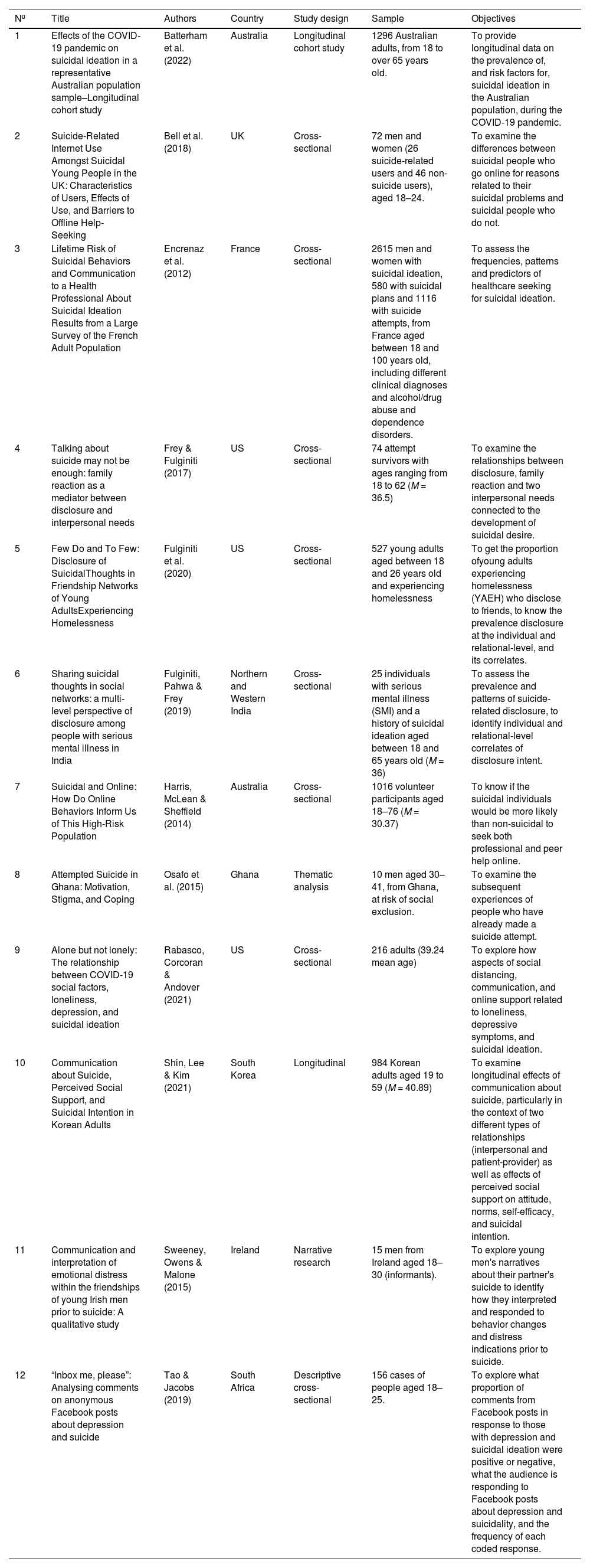

Main features of the selected studies.

Articles were included if they (a) covered adult participants between 18 and 24 years old (young adults) and between 25 and 40 years old (early middle adulthood), age range defined by Erik Erikson29 like young adulthood, (b) included the variables “communication” and/or “social support”, (c) collected information directly from people who survived previous suicide attempts or indirectly through informants, and (d) were published in a peer-reviewed academic journal, written in English. Articles were excluded if (a) the study was a review or meta-analysis, (b) the study tried to validate tests, models or psychological theories, (c) the study targeted specific populations (e.g., war veterans) or did not specify the selected age range, (d) the participants demonstrated self-harm without suicidal intention, (e) the study assessed intervention programs, (f) the main risk factor for suicide was substance abuse or treatment with medication, (g) the study focused on people bereaved by suicide.

Data analysisDue to the heterogeneity of designs, objectives, measures and evaluation methods, the studies could not be combined into a singular meta-analysis or pooled calculation. For this reason, a qualitative analysis was carried out to summarize and integrate the findings. We first showed their main characteristics, categorized by the type of design, and then we organized the frequency of risk and protective factors included in them to understand the overall percentage of occurrence. Finally, we presented the different evaluation measures for the most relevant variables, which we tried to describe their approach in the samples of each study.

ResultsThe bibliographic search initially had a total of 436 results. Of these, 295 articles were selected after eliminating duplicates. Abstracts were reviewed to select studies for inclusion, and results were obtained from the full text. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria and checking the title and abstract for each one of the studies, 12 studies were finally incorporated into this review. Fig. 1 presents the PRISMA Flow Diagram of the article selection process.

Table 1 describes the main features of the selected articles. Of the 12 articles, we found 3 qualitative and 9 quantitative studies. And the sample size ranged from 15 to 2615 participants.

Most of these studies were conducted in upper-middle-income countries (n = 10; 83.33 %), and the remaining two in developing/lower-middle-income countries. Most studies were conducted in Europe and America: UK (n = 2), France (n = 1), USA (n = 3). Two studies were conducted in Asia (India and Korea), two studies in Africa (Ghana and South Africa) and the remaining two in Oceania (Australia). Therefore, although the final sample is small, it covers the population of each habitable continent.

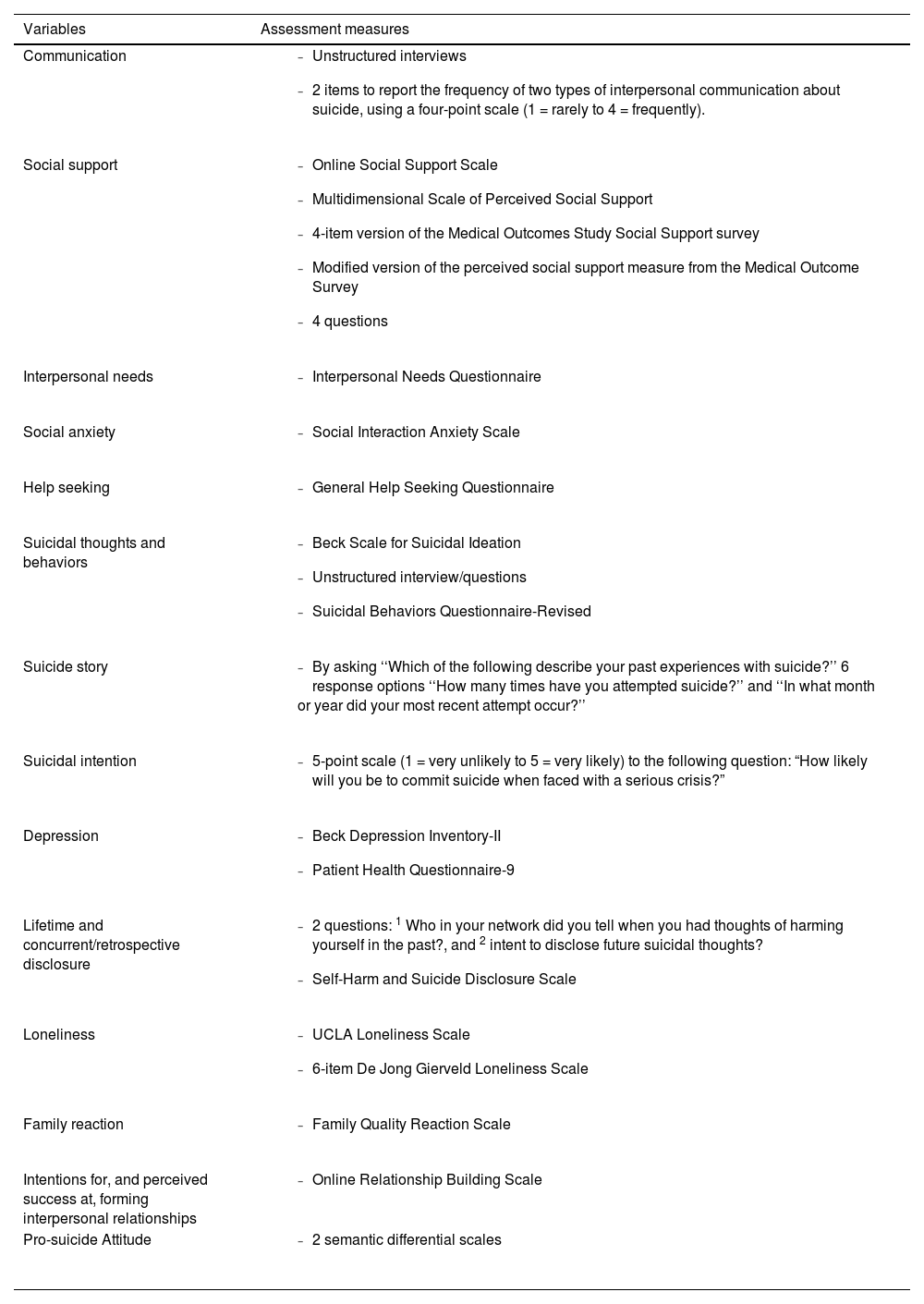

Studies that did not separate their results by age group were excluded because it biased the chosen age range. Data in the included studies were obtained from health services, national surveys, police reports, social media and educational settings, although some participants were also recruited through the snowball technique. These studies included different measures to assess the variables. In Table 2 the measuring instruments of the main variables are shown.

Main variables of interest and their assessment measures.

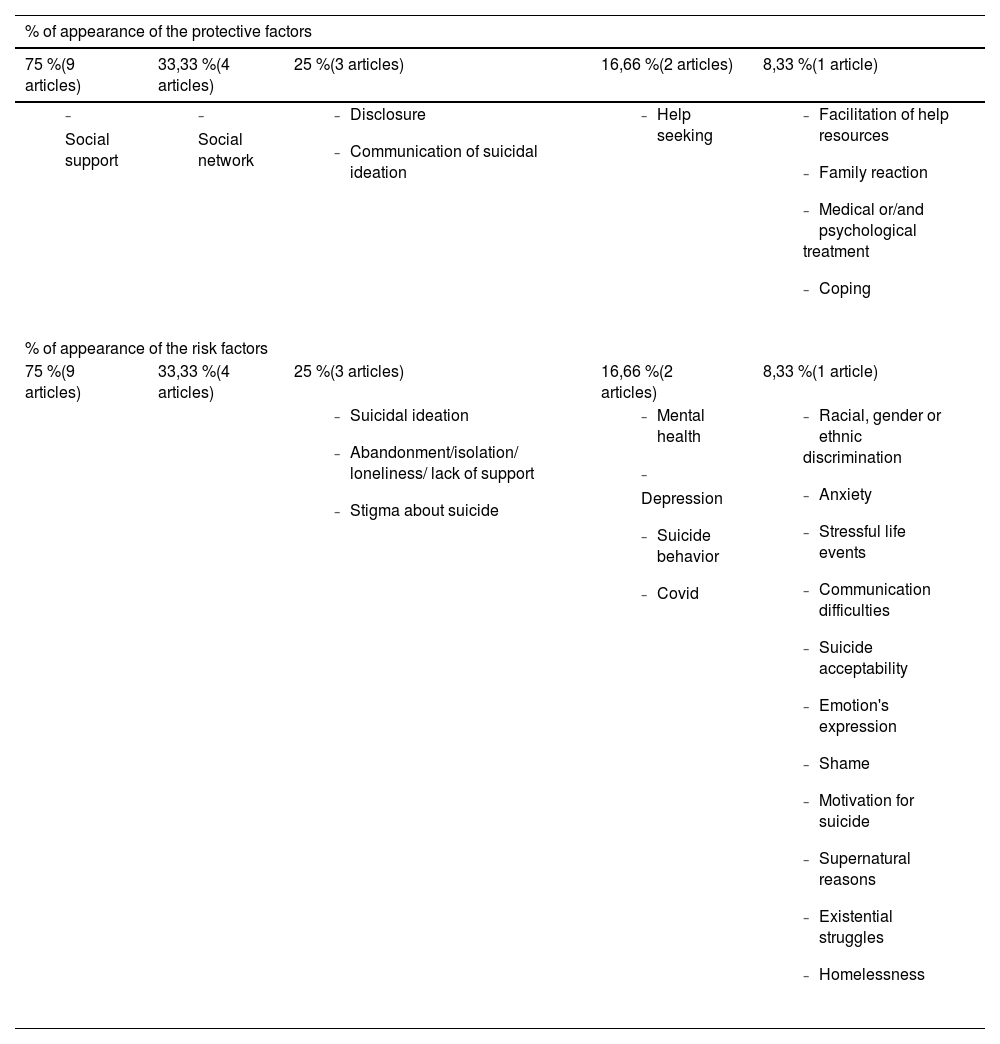

Covering the broad spectrum of suicidal behaviour, we found that the half of the final sample of articles included suicidal ideation,30–34 1 article included attempts,35 1 ideation and attempts,36 3 articles included this two and also plans,37–39 and 1 article only suicidal intentionality.40 The frequency of appearance of the rest of the variables is reported in Table 3.

Frequency of appearance of risk and protective factors in the final sample of articles.

Among the variables that could have both a protective and risk function, several papers identified closeness with others as a protective factor and recommended not leaving the person alone in life-threatening circumstances.30,36 However, Encrenaz et al.37 found that people who spend much time with the person at risk may underestimate or not realize the seriousness of their condition. Despite the closeness that may exist with others, this proximity can be a barrier to perceiving changes in the individual's mental state or behaviour, focusing on the 18–30-year-old age group. Bell et al.36 also highlighted the underestimation of the severity of the receiver as a barrier to effective interaction, but adding the difficulties in expression and the worries of the sender about being judged.

An important part of communication is the emotional expression, complementing the interpretation of emotions that appears in the study by Sweeney et al.,33 and being negatively associated with suicide. But sometimes culture interferes with what is accepted in a society. As an example of this, in the study by Shin et al.,40 the Korean participants were more willing to engage in a conversation about suicide with friends, family and coworkers, the more permissive they were toward this behaviour. The outcomes of communication about suicide could vary depending on social support perceived.40 So, when this support was lacking, talking about suicide with relatives, friends or even with healthcare professionals, was more likely to strengthen the idea of suicide as an acceptable solution.

Another important barrier to providing social support is only mentioned in the study of Osafo et al.,35 and it refers to some type of discrimination (by race, ethnicity or gender), which could make it difficult for the individual to integrate and favour the risk factors associated with suicide.

In the sample used by Fulginiti et al.31 all the participants experienced suicidal thoughts with an average friendship network size of 2.50, and only 30 % of them had disclosed such thoughts to some of their friends. Although it was not always done immediately before the attempt, it was sometimes done retrospectively as well, so it could not always be interpreted as a search for help. In any case, the participants were also more likely to disclose during a suicidal crisis to friends who perceived it as a source of emotional/informational support. This would fit with hypotheses in suicidal youth that avoiding discussions about these issues was seen as a sign of reluctance to seek assistance, becoming more acute the more severe the levels of depression or suicidal tendencies of youngsters.41

Although already in the context of COVID-19, Mortier et al.42 found the lack of social support was associated with active suicidal ideation, plan or attempt during the first wave and a higher prevalence of these behaviours among those with a previous mental disorder. Batterham et al.30 found that 60 % of young adults18-34 experienced suicidal ideation due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on work, social relationships, loneliness, and recent adversity, especially among females. Rabasco et al.32 conducted a study with a mostly female sample, focusing on late 2020, and found that social contact, whether in person or electronic, serves as a protective factor against loneliness, depression, and suicidal ideation.

Bell et al.36 included the social connection through new technologies, finding both positive and negative aspects of these tools, as well as face-to-face contact. Addressing this issue, Harris et al.39 and Tao & Jacobs34 found that the online space was a resource to resort to when the person does not have social support outside, which happened with people at risk of suicide, especially women.

Regarding the gender of the person with which more communication was established and offered more possibilities to share feelings and personal issues, mostly the female sex coincided, as can be seen in Sweeney et al.33 and in Frey & Fulginiti38 with mothers, sisters and grandmothers, followed by some male figures in a lower percentage. Suicide-related disclosure was positively and moderately correlated with family reaction.

Family members seem to be chosen as common suicide-related disclosures’ recipients. Fulginiti et al.43 found this in particular too, despite the fact that, in the future, friends were identified as more likely to receive this type of revelation than family, but in their sample a little percentage (14 %) of social network members as sources of any kind of social support, discovering also very low percentages of explicit suicide-related disclosure among these (17 %).

Bell et al.36 found that communication with the family was easier in the group without suicidal behaviour than in the exposure group. As we can see in the study of Fulginiti et al.,31 regarding the people who were used for the lifetime disclosure, they coincided in choosing friends or relatives in the first places, followed then by professional providers or other kinds of people. The more serious the suicidal behaviour was, the more likely it was to be reported to more specialized people.37 Stigma associated with suicide was identified as a barrier to communication, also mentioned in Osafo et al.35 Just the opposite can be seen in the study of Shin et al.,40 where talking frequently about this topic (indirect effect of communication about suicide) with significant others leads to a perception of greater approval of this behaviour. However, this relationship of variables could not be demonstrated when the communication about suicide was made in front of health professionals, which was quite small in comparison. Encrenaz et al.37 found a lower frequency of expression of suicidal ideation in front of professional among men, especially in the 18–30-year-old age group. Those who did reported such expression seemed to have also shared it with friends or family.

Studies that dealt with the JITS, as in Frey & Fulginiti,38 found a greater relevance of the disclosure and family reaction over the sense of belongingness and the perceived burdensomeness, both variables related to suicide. A quality reaction of the family to the disclosure of the suicidal idea/intention could interfere with these two variables mentioned, reducing the risk. In another study where Fulginiti was an author, Fulginiti et al.,31 we can find similar variables associated with greater suicide-disclosure depending on the type of it (concurrent or retrospective), like history of unmet mental health needs30,43 and reveal it to a close friend who is perceived as a source of tangible social support.

Other barrier to an effective communication of the suicidal behaviour that were only mentioned in Sweeney et al.,33 was the alcohol consumption, used to facilitate communication with others on issues related to the problem addressed (seeking help).

DiscussionOverall findings and implicationsThis study aimed to investigate how communication and social support related to suicidal behaviour have been studied in young/early middle adults and synthesize the evidence using a systematic search of studies of this subject since 2012.

A comparison of the results of the studies is presented, showing key factors involved in the development of these suicidal behaviours and gender differences. The studies had a common theme linking communication difficulties of the individual with greater risk for suicide and revealed the importance of social support and seeking help.

The results indicated that social support, whether from professionals, family or friends, even from acquaintances or strangers on social media, can be a very important protective factor against suicidal behaviour, just as other studies have validated its protective role on this fatal outcome in the presence of other risk factors.44 The quality of communication was also found to be important, especially due to the difficulties encountered in clearly communicating the intentions and seeking help. Consequently, the major reason for this negative behaviour seemed to lie in the absence of social resources, resulting from these factors.

In addition to the financial, social and work impairment, factors related to COVID-19, other risk factors such as loneliness, life adversities and previous mental health conditions were discussed. Although this review did not specifically examine the effect of COVID-19, we know these risk factors have become more severe during the pandemic.45 Social distancing to prevent the spread of COVID-19 can be a barrier to social support, sustaining Mortier et al.42 results, which makes dealing with the risk factors we identified more important. Just as Hobfoll emphasized in his theory, the effectiveness of social support is manifested in its ability to support the conservation of additional resources.45 Therefore, in the situation of COVID-19, in which social contact was restricted, it would indirectly influence the loss of other protective factors.

The communication difficulties mentioned were reminiscent of the findings by Wasserman et al.46 on the inability of young adults to communicate in words their suffering and resorting as a last option to suicide, and other influential variables such as the stigma of this communication and the relational characteristics discloser–recipient.47 And following the line of the Conservation of Resources Theory, it can be explained by the relation between the perception of lacking resources and the use of dysfunctional or ineffective strategies to address problems, such as retention of the problem to oneself and self-accusation.48

The resources that young people valued as most important were generally those they reported possessing, including the presence of friends, the support of their parents, and the availability of housing and food. It has already been demonstrated the important moderating role that the social support of parents can play in this problem of their descendants.49 In contrast, they attributed less importance to resources such as employment, participation in organized groups, having leadership responsibilities, and maintaining a routine that motivates them positively.

Regarding the gender differences found in the results in reference to the fact that women tend to be more frequently the recipients of requests for help from men, and that these in turn are the greatest seekers of professional help, it seems consistent with the findings in the literature about the stigma of men asking for professional help.50,51

Thus, the need for healthcare professionals to detect suicidal risk in routine care becomes more evident, as does the need to reduce stigma and taboos around suicide in older generations that prevent young people from seeking help from trusted family members and friends.

Taking into account the practical implications included in the selected studies, potential methods to improve the role of communication and social support in suicide prevention strategies include: family interventions in a complementary way to individual treatment; improvement in health care promotion in young people; a focus on perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness when developing communication strategies; implementation of suicide prevention programs in environments where these age groups converge (e.g., universities); and Internet awareness campaigns and moderators, since the use of technology also has an important influence on the increase in this type of undesirable behaviour in youngsters.52 In this way, this systematic review intended to facilitate, with the data presented, a broader vision of the approach to social support and communication in the context of suicide in young adults so that it can serve to guide when devising intervention strategies in this vulnerable age group.

Being able to speak openly with a close person without fear of being reprimanded for it, belittled or stigmatized, helps to reduce the taboo and stigma surrounding suicide and facilitates social support. Prevention policies should take this into account.

The findings in this review allow us to identify common aspects that can be very useful when designing suicide prevention strategies in the 18–40-year-old age group, beyond the heterogeneity of suicidal behaviour. Health professionals involved in these interventions could consider results of this type both in preventive and in the treatment process, since they have already used factors like availability of social support and communication of suicidal intent when assessing suicidal risk.53

LimitationsThere are some limitations to this review, one of them is the heterogeneity of the included studies and the evaluation measures used for similar variables, which may limit the overall conclusions. However, this variability in the methodology of the studies can enrich the discussion and offer a broader vision of the problem addressed. Moreover, articles in languages other than English were not considered.

On the other hand, the main limitation of most studies was the lack of generalizability. Many of the studies had very limited samples or were chosen through a non-random process. Although the origin of the samples included in the chosen studies is not the same (USA, Australia, India, UK…), given the small total number of studies chosen, they do not allow to cover an estimable quantity for their generalization. Also, studies such as that of Batterham et al.30 already have a bias as their sample is small.

Furthermore, most studies were cross-sectional designs which make it difficult to establish causal relationships between the variables studied, as well as to explore the antecedents at the time of evaluation and possible future variations.

Future research linesFuture research should consider studies with more specific age groups to analyse in depth the importance of the most prominent variables. Such studies could also evaluate more regularly those variables, which may involve relevant aspects of effective communication when seeking help that can be key elements when designing intervention strategies.

In addition to the current findings, it would be of interest to conduct studies concerning the response of individuals when asked for help, including their reception and management of such requests. The way assistance is received and processed may yield varying outcomes, thereby warranting further investigation. To be more concise, it would be necessary to analyse the gender differences based on the phase in which help is requested and even the differential request itself between men and women. The gender management of the stigma created by the disclosure of suicidal ideation would also provide interesting data.

In addition to existing research, it is crucial to identify aspects of interpersonal competences involved in the communication of suicidal behaviour and the establishment of necessary social support that have not been specifically addressed yet, thereby filling research gaps and achieving a more complete understanding of the suicidal behaviour to design interventions to address this problem.

ConclusionThe results of this study can be useful both for people with suicidal behaviour and for those from the closest social and relational context. The process of building social relationships that favour communication from an early age in the family and school nucleus will have an impact on how we develop to face or prevent problems as we mature. It would be convenient to offer opportunities to learn communication and relational skills in environments that favour clear and effective interpersonal communication, while at the same time facilitating the anchoring of social support groups.

Improved interventions based on these findings are particularly urgent in men due to their lower propensity to seek help, lower levels of social support, greater difficulties in communicating these thoughts and intentions and higher rate of completed suicides.

By improving communication skills, reducing the stigma surrounding mental illness and suicide, and educating people at risk about better strategies for sharing their needs and seeking help, the community can be more effectively engaged in suicide prevention and progress can be made on reducing this preventable and tragic cause of death.