The nurse-to-patient ratio planning presents a global challenge in healthcare systems, with significant disparities across countries. It is a widely studied phenomenon, yet methodological and conceptual gaps persist. In Spain, the nurse-to-1000-inhabitant ratio (6.2) remains below the OECD average (8.8), resulting in an estimated shortage of 100,000 nurses. This issue is exacerbated by political decisions influenced by economic, cultural, and organisational factors.

This work aims to review existing methodological approaches for determining nurse staffing levels, identifying their strengths, limitations, and potential improvements to ensure the efficient and safe allocation of resources.

Five methodological approaches are analysed: expert judgement, distribution-based methods, time measurement, correlation between staffing levels and adverse events, and stratification by patient complexity. National and international data are compared, and their impact on safety, efficiency, and costs is assessed.

The study confirms that higher nurse staffing levels reduce mortality and adverse events. Models based on patient complexity, such as INICIARE, provide a more precise and adaptable approach.

In conclusion, nurse staffing planning should be based on a model that stratifies patient complexity levels according to care dependency while minimising institutional variability. It should be linked to clinical outcomes, patient safety, staff competencies, and workforce stability. Additionally, research should extend to primary and social care settings, where evidence remains limited.

La planificación de la ratio enfermera-paciente es un desafío global en los sistemas de salud, con marcadas diferencias entre países. Es un fenómeno ampliamente estudiado, objeto de múltiples aproximaciones, aunque la mayoría con importantes lagunas metodológicas y conceptuales. En España, la ratio de enfermeras por cada 1000 habitantes (6,2) es inferior a la media de la OCDE (8,8), lo que genera un déficit estimado en 100,000 enfermeras. Este problema se agrava por decisiones políticas influenciadas por factores económicos, culturales y organizativos.

Este trabajo tiene como objetivo revisar los enfoques metodológicos existentes para determinar la dotación de personal enfermero, identificando sus fortalezas, limitaciones y posibles mejoras para garantizar una asignación eficiente y segura de recursos.

Se analizan cinco enfoques: juicio de expertos, métodos distributivos, medición de tiempos, relación entre dotación y eventos adversos, y estratificación por complejidad del paciente. Se comparan datos nacionales e internacionales y se evalúan impactos en seguridad, eficiencia y costos.

El estudio confirma que mayores dotaciones enfermeras reducen la mortalidad y los eventos adversos. Modelos basados en la complejidad del paciente, como INICIARE, ofrecen un enfoque más preciso y adaptable.

Como conclusión, la planificación de la dotación enfermera debe basarse en un modelo que estratifique niveles de complejidad de pacientes, por dependencia en cuidados, minimizando la variabilidad institucional. Es clave vincularla a resultados clínicos, seguridad del paciente y factores como competencias y estabilidad del personal, y extender estos estudios a Atención Primaria y al ámbito sociosanitario, donde la investigación en estos aspectos es mucho más limitada.

Planning nurse/patient ratios is a key aspect of healthcare systems, with common contemporary characteristics imposing a global challenge. It is a widely studied phenomenon with multiple approaches, although most have significant methodological and conceptual gaps.1 Moreover, even those that provide some insight are rarely implemented, since they are supported by short-term economic policies, further sustained by the scarcity of pertinent economic evaluation studies. Added to this is the loss of empowerment and/or lack of nursing leadership in decision-making bodies, despite repeated guidelines from the World Health Organisation (WHO) urging states to meet this requirement.2

It is also striking that the planning for the distribution of healthcare professionals in a country or region can vary widely when addressing highly similar health problems and requirements. One only has to look at the doctor-to-nurse ratios or nurse-to-inhabitant ratios, both in Europe and in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, to quickly identify this phenomenon. As an example, in 2023, in Spain, there were 1.1 nurses per doctor whereas in countries like Finland and Luxembourg, the ratio reached almost 4 nurses per doctor. At a rate of 6.2 nurses per 1000 inhabitants, these data place Spain in 26th place out of 38 OECD countries, where the average for the member countries is 8.8 nurses per 1000 inhabitants. According to data from the Ministry of Health, Spain would need to increase the number of nurses by around 100,000 to match European ratios (Eurostat 103,634, OECD 134,865, and WHO 130,961), requiring between 22 and 29 years to reach the EU-27 average (assuming a stable population and linear growth).4

Behind this organisation there are always political decisions that attempt to respond to different stakeholders, pressure groups, firmly established organisational cultures, and gender mandates. There is abundant evidence of the social stereotype of an eminently feminine profession, in which the phenomenon of tokenism is frequently expressed. This gender bias permeates organisational culture and can influence perceptions regarding decision-making and nurses' participation in health policies and governance.5–7 Over a decade ago, some authors such as González López-Valcárcel et al., carried out multiple strategic analyses, documenting the human resources planning policies that should be followed in Spain, with a permanent recommendation to redistribute functions and responsibilities.8

In short, the nursing discipline faces a methodological and conceptual challenge in reorganising nurse ratios in a decision-making context that does not favourably align with any sound methodological proposal. It is important acknowledge these aspects because, without doing so, any attempt to transfer them to clinical practice will be unlikely to succeed, and this could contribute to discouraging research into such a complex phenomenon.

The purpose of this article is to provide a description and review of each of the existing methodological approaches for estimating the nurse/patient ratio, with their advantages, scope, limitations, and possible future lines of research needed to address the existing gaps.

Methodological approachesThe indicators internationally used to measure this phenomenon are the nurse-patient ratio or Nurse Staffing Levels (NSL) or nurse-to-population ratio. The latter is the most extensive method for estimating the population-adjusted nursing workforce. It is widely used by various international organisations (WHO,9 OECD,3 Eurostat,10 and the National Institute of Statistics11) in cross-country or regional assessments.

A more profound look into the methodological aspects of the study, analysis, and organisation of nursing resources in health services reveals that these approaches can be grouped into five broad approaches with specific characteristics in no specific hierarchical order:

- 1

Methods based on expert judgment and resource comparisons between similar services.

- 2

Distributive methods based on volume of professionals with respect to the different levels of adherence of the people receiving their services.

- 3

Methods based on time-unit or time-dependent approaches: in which nursing activities and interventions are identified, assigned time units, and, after a detailed frequency count, estimates of the time required by nurses to provide services to different groups of patients (“workload”) are obtained.

- 4

Methods based on the identification of negative health outcomes and clinical safety: These are based on volume-based distributive approaches, but link them to undesirable outcomes resulting from an insufficient number of nurses, or the inability to provide certain care considered necessary but which, due to lack of resources, is impossible to provide—the so-called care rationing phenomenon, care left undone, or missed-care.

- 5

Finally, methods based on stratification according to levels of care complexity. This approach, while taking into account variables used in other approaches, incorporates a focus on the individual's care needs and/or dependency.

All healthcare systems routinely organise their staff through a retrospective comparative analysis of historical staffing levels. This means that, unless there are substantial changes in the service offering, or if there are no demands from the managers themselves toward those most responsible for funding, or from staff, unions, professionals, users, etc., the traditionally established staffing levels are maintained over time. This procedure routinely involves comparisons with similar services within the hospital itself or with other hospitals with the same complexity. It is also common for different scientific societies, professional organisations, or even the Ministry of Health itself, to make recommendations on the advisable number of nurses needed in different contexts. They do this based on diverse methods, often extrapolated from studies in other countries, or from literature reviews, established with consensus methods or supported by time-measurement systems.12–14

The problems arising from these approaches emerge immediately, as the origin of the criteria leading to the current staffing is often unknown and has rarely been compared with any rigorous analysis. Since it does not involve any assessment of patients or interventions delivered by nurses, it cannot take into account the heterogeneity of care demand. Comparisons are usually made between “similar” hospital units, a criterion that generates considerable variability due to the portfolio of services offered, organisational models used, unit structures and distribution, and, above all, the funding and public spending invested in human resources. Fig. 1 shows a 2010–2023 comparison of the number of nurses working in hospitals by autonomous community in Spain. It demonstrates the heterogeneity of staffing maintained over time, with no demographic or epidemiological reasons justifying such extreme variations (hospitals with 5.8 nurses per 1000 inhabitants compared to others with less than 3.3 nurses per 1000 inhabitants). This graph shows an increase over time, similar across the autonomous communities, which may be due to the use of the aforementioned methodological approach.

Although efforts have recently been made to increase the number of nurses: 11% in primary care, 36.9% in emergency care (112/061), and 27.2% in hospital care, recent data published by the Ministry of Health in its report “Current Situation and Estimated Need for Nurses in Spain 2024” show that the ratio of nurses per 1000 inhabitants in Spain remains lower than the European Union average.4

Comparisons between centres, even when adjusted for complexity indices (generally by DRGs, with their well-known limitations in explaining the need for nursing care15–17), do not allow for a planning framework for nurse ratios with sufficient validity and reliability and are insensitive to the distribution of different levels of dependency and vulnerability that determine patient complexity. They tend to obey professional judgment criteria, which are sometimes highly subjective and is unable to distinguish which staffing levels are optimal for achieving better care outcomes.18 As a result, these approaches often generate frequent situations of under- or overstaffing, without adequate regulatory mechanisms to prevent these scenarios. Paradoxically, despite its methodological weaknesses and limitations, planning based on “historical staffing data” (mostly derived from subjective criteria) is one of the predominant approaches in most NHS centres. A side effect of these methods is that nursing managers, to address inadequate staffing, resort to the mobility of nurses between units and services with a frequency, discretion, and immediacy to meet operational care needs, which challenges the professionals' abilities to address the wide diversity of skills, sometimes from highly specialised environments, and may affect some aspects of clinical safety.

Distributive methods based on the number of professionals with different levels of aggregation (ratios)These methods focus on providing a minimum number of nurses to care for individuals by grouping them at different levels. From the perspective of international comparisons, they provide a useful overview, even enabling the analysis of the number of nurses compared to other professionals. They also allow for ecological analyses of certain indicators of global health, financing, or accessibility to services.19 Thanks to these methods, at the macro-management level, it is possible to compare the number of nurses between different regions or organisations.20 Thus, in Spain, the average number of nurses per 1000 inhabitants is always lower than the European average, ranging from 1.8 to 3.1 fewer nurses per 1000 inhabitants depending on the sources consulted, as shown in Fig. 2.

Comparison of the number of nurses per 1000 inhabitants. Sources: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Healthcare resources. Paris: OECD; 20233. World Health Organization. Global Health Workforce statistics database, 2023. Last updated 21 May 20259. Eurostat. Database - Health. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 202310. Ministry of Health. Primary Care Information System (SIAP for its initials in Spanish), Specialized Care Information System (SIAE) and Statistics on Emergency Services 112/061 of SIAP.11

There are also limitations to these methodologies, derived from how each source conceptualises the different nursing professional categories. An example is the OECD's division by professional status (practising nurses, professionally active nurses, nurse licensed to practice) or by category (professional nurses, which would be the equivalent of Spanish registered nurses: they assume responsibility for planning and managing care, including the supervision of other healthcare professionals; or associate professional nurses, which includes other categories of nurses who work under the supervision of the former and would be the closest equivalent to the Spanish TCAE). The OECD allows for a breakdown by these categories to avoid the widespread confusion associated with calculating nurses per capita by grouping all possible categories together. Eurostat uses the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO), which distinguishes between professional nurses, midwives, and associated nursing professionals, as well as staff working in social and health care, etc.21

It also allows for a comparison of structural differences between autonomous communities, with ratios of nurses working in the NHS of 4.6 per 1000 inhabitants, ranging from 7.4 in the Autonomous Community of Navarra to 4.1 in Andalusia, as shown in Fig. 3.

However, the excessive level of aggregation prevents more detailed analyses for decision-making at the meso- or micro-level, or at the level of care and complexity between patients/population, located in the same enclave or assigned to the same care unit. Thus, in primary care in Spain, according to data from the Ministry of Health, the average ratio of nurses per 1000 inhabitants currently stands at .70, or approximately 1370 inhabitants per nurse, with variations between autonomous communities from 1112 (Canary Islands) to 1950 (Madrid).22 Criterion that lacks the necessary adjustment in relation to factors that increase the demand for services, such as the presence of an aging population, areas with structural needs derived from the presence of poverty and social marginalisation, geographical dispersion, etc.23

At hospitalisation level, in Spain, a study conducted by Cruz et al.24 showed a persistent shortage of nurses in acute care units, using as a reference the Ministry of Health13 standards which, in turn, were based on inconsistent methods. However, the patient-to-nurse ratios obtained were significantly higher than those typically used in international studies on the impact of nurse-to-patient ratio legislation. This research highlighted structural differences between hospital indicators, which can give us an idea of the robustness of systems by region. Thus, for example, only Navarre met the nurse-to-patient ratio recommendations in conventional hospitalisations during the Monday-to-Friday morning shift, although the data were more diverse among the other shifts.

Numerous analyses have been conducted regarding hospital care, albeit with the important limitation of the reference ratios used. Internationally, some experiences have been evaluated in countries that have legislated minimum patient ratios, including one of the pioneering initiatives, such as that used in the state of California. An increase in the hiring of nurses has been reported, with decreases in mortality and failure to rectify adverse events (AEs), as well as increased costs.25–27

More recently, an assessment of the impact of nurse/patient ratio legislation in hospitals carried out in Queensland (Australia) showed that in 231,902 patients at 2 years, mortality decreased significantly (OR: .89; 95% CI: .84–.95); readmissions increased in hospitals that did not implement the ratio regulation (OR: 1.06; 95% CI: 1.01–1.12); length of stay decreased RR: .95 (95% CI: .92–.99). There was an increase in staff costs of €21,126,576, but €43,252,673 was the amount saved in avoided costs due to the decrease in AEs, representing a total saving of €22,126,097.28 This study fills an important gap in the evidence based on the impact of ratio regulation on costs and the avoidance of adverse events. However, some weaknesses remain, as the application of ratios with overly generic standards could lead to inequalities between units with a heterogeneous distribution of patient complexity. The study design by McHugh et al., although consistent in terms of sample and assessments, did not randomise groups (a highly complex, though not impossible, issue in studies of this type).

Along these lines, a bill on nurse ratios was even presented in Spain in 2019, following similar legislative initiatives in other countries. This bill proposed minimum ratios based on different healthcare settings, both in primary care (1500 inhabitants per nurse) and in hospitals (a maximum of 6 patients per nurse in inpatient units, 2 per nurse in critical care, 3 patients per nurse in post-surgical resuscitation units, or 3 nurses per operating room).29

Many factors remain to be seen here. First, whether this legislation will ultimately be approved. Second, how it will be applied in the different Autonomous Communities is unknown. Third, its potential impact will need to be assessed if it is developed and implemented. Furthermore, despite the expected benefits in terms of reduced adverse events, mortality, length of stay, costs, together with professional satisfaction and motivation, institutional and corporate resistance is likely, as well as uncertainties about the “willingness to pay” from the perspective of public acceptability of measures of this type. However, given the high level of public satisfaction with nursing services in healthcare barometers, consistently reported over time,30 public rejection of a measure of this nature is unlikely.

An approach based solely on distributive models does however leave out factors, to be described later, which have a significant impact on the quality of care and outcomes, such as work environments, professional practice models, and interdisciplinary relationships. These factors can foster or restrict nurses' autonomy and leadership which are key elements highlighted by recent research, that will be discussed later.

The studies carried out in Spain underline that the factors that determine nursing staff have more to do with the characteristics of the hospitals themselves than with those of the patients they serve.31

Methods based on measuring time or time/dependentsSince the 1970s, numerous instruments have been designed to quantify the care required by patients. These instruments are based on activities planned or carried out by nursing teams and evaluated in time units. These instruments are either directly measuring the time spent caring for the patient or estimating the time to be consumed through care indicators. They include32: Project Research in Nursing (PNR), Care Individualised to the Person (SIIPS), SIGNO II, Care Dependency Scale (CDS), Grace Reynolds Application and Study of PETO (GRASP), Time Oriented Score System (TOSS), and Nursing Activities Score (NAS). Medicus, Exchaquet, Montesinos method, Indices de Pondération des Soins Infirmiers (IPSI), Dependence Nursing Scale (DNS), Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System (TISS), Nine Equivalents for Nursing Manpower Use (NEMS), Nursing Care System (SAF), Nursing Intervention Scoring System (NISS), OMEGA System, and Crew System, Nursing Care Recording (NCR).

These task-based systems have a limited capacity to capture complex aspects of nursing practice, such as clinical judgment or the simultaneous delivery of multiple interventions in a single procedure.

More recently, cross-cultural validations and/or new approaches have increased,1 which continue to perpetuate methodological weaknesses because their underlying design has the same perspective (time/dependency). Furthermore, the superiority or greater consistency of one instrument over another, or the rigor of its measurements, has yet to be demonstrated. Thus, O'Brien et al., three decades ago, observed how four different systems evaluated on the same patients offered differences of 4.5 h per day in care demand.33 Some instruments of this type are the Nursing Activities Score (NAS),34 Northwick Park Dependency Score (NPDS),35 RAFAELA System, VACTE©,36 Personalization of Care Index (IPC), Individual Care Scale (ICS), or proposals based on the conceptual framework of the Nursing Intervention Classification (NIC) taxonomy, such as that developed by Perroca et al.©37 or the MIDENF instrument.38

In this section, we would like to highlight the studies by Juvé-Udina et al., which, although initially developed as a natural language-based taxonomic system (ATIC language) for problem identification, have subsequently evolved to translate the identification of these problems, along with the acuity stratification of DRGs adjusted for severity and mortality, into hours of nursing care per patient per day.39,40

In short, most of these methodological approaches:

- 1

Are poorly supported by conceptual frameworks of care, highly focused on nursing activities, and, in order to estimate care, focus on the activities performed by professionals rather than on patient states or responses. This is compounded by the institutional variability of clinical practice (e.g., units in which a given intervention is performed by nurses, while in others, the same intervention may be performed by the medical team, depending on the organisational culture of the centres and units).

- 2

Even the time measurement systems themselves have demonstrated excessively wide variations in the times assigned to the same intervention, as identified by Myny et al.41 and serious problems with interobserver reliability.42 Furthermore, many of these systems do not take into account the added intensity of indirect care or the time required by the nurse to organise care, complete medical records, update the care plan, hand off and transfer patients, and review safety-related aspects (resuscitation equipment, drug expiration dates, etc.).

- 3

Also, these systems are insensitive to the fluctuations that may arise from the level of professional experience of the nurses performing the interventions included in the different measurements. This factor that can completely distort the measurements taken. Furthermore, the variability and heterogeneity of organisations can generate more or fewer interventions (a simple variation in the frequency of a protocolised intervention performed differently in two different hospitals—a situation not at all uncommon—automatically generates variations and different staffing needs).

- 4

As a result, the actual effectiveness of these methods does not offer a robust solution for addressing the allocation of nursing resources, and it is unknown whether the implementation of these systems would result in improvements in patient health outcomes today.

This approach is based on the premise that if there are not enough nurses with appropriate qualifications, negative outcomes will occur in indicators relevant to nursing practice.43 This outlook has been increasingly and extensively developed throughout the world since the end of the last century and has provided very solid evidence regarding the consequences of nursing understaffing on negative patient outcomes. Thus, multiple studies conducted in 30 countries over two decades with thousands of hospitals, patients, and nurses demonstrate a direct association between the presence of a sufficient number of adequately qualified nurses and a reduction in adverse events such as mortality, infections, haemorrhages, thrombosis, pneumonia, medication errors, etc.1,44,45

After more than two decades of research in this area, the causal relationship between the number of nurses and the occurrence of adverse events and mortality is increasingly solid.46 In OECD countries, it has been found that approximately 15% of hospital expenditure and activity is directly derived from AEs. Thus, in well-funded and technologically advanced hospital settings, approximately one in 10 patients suffers some type of harm, and improved patient outcomes translate into lower costs for the hospital.47,48

These results are in line with data presented in the technical report “Improving Patient Safety in the European Union,” commissioned by the European Commission in 2008, which found that the percentage of AEs in hospitalised patients ranged between 8% and 12%. An estimated 4.1 million patients in the European Union suffer healthcare-related infections each year, and at least 37,000 people die from this cause.49 These infections account for 20% of all AEs in hospitalised patients. In Spain, several studies have assessed the risk of patient care, promoted by the Patient Safety Strategy of the National Health System (NHS),37 such as the National Study of Adverse Events Related to Hospitalisation (ENEAS), the Study of Adverse Events in Primary Care (APEAS), the Study on Adverse Events in Nursing Homes and Social-Health Centers (EARCAS), and the Study of Safety and Risk in Critically Ill Patients (SYREC), and others, such as the Study of Adverse Events in Emergency Departments of Spanish Hospitals (EVADUR), promoted by the Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine. All these studies agree on the high degree of preventability in the production of AEs, ranging from 50% in hospitals to 70% in primary care and emergency departments.

One of the most relevant studies is that of Harrison et al.50 with 231,000 nurses in California, Florida, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, which showed that the probability of surviving to discharge with good cerebral function after CPR increased substantially in those services where nurses had higher levels of training, in those with 70% graduate nurses it increased compared to those with 40% graduate nurses. Furthermore, the probability of surviving to discharge would be lower for patients in hospitals with caseloads of 6 patients per nurse, compared to hospitals with 4 patients per nurse. Derived from this philosophy, instruments such as the Nursing Practice Model Questionnaire (NPMQ),43 Intensive and Critical Care Nursing Competence Scale (ICCN-CS-1),51 Nurse Professional Competence (NPC),52 Healthcare Productivity Survey (HPS), Inventário de Competências Relacionais de Ajuda (ICRA),53 have emerged. Also noteworthy is the RN4CAST study, carried out in 488 hospitals in 12 European countries, including Belgium, England, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland, which has provided valuable insight into the relationship between nursing staffing and AEs. With a sample of nearly 34,000 nurses, the findings showed an increase in the probability of dying for each additional patient assigned to a nurse. Moreover, an increase in the number of graduate nurses decreased this probability. This link implies that patients in hospitals with 60% graduate nurses and an average of 6 patients per nurse, are 30% less likely to die than in hospitals with 30% graduate nurses and a ratio of 8 patients per nurse.54

Although not aimed at nursing human resource management, increasingly more predictive tools for the onset of AEs that are sensitive to nursing practice are being proposed, such as the Predisposition to the Occurrence of Adverse Events Scale (EPEA), VALENF,55 PREDICUIDD,56 the Global Trigger Tool,57 or the extension and adaptation of early warning scales. However, sufficient research is needed to determine the extent to which these tools could act as models of the distribution of nursing resources in different contexts and practice settings.

Care missed or left undoneIn the development of this line of research, the concept of care left undone or missed nursing care emerged, referring to care missed or not performed and how the omission of any aspect of care leads to poor patient outcomes.58 The findings of Cho's 2015 study, comparing units with 7 patients per nurse and others with 17 patients per nurse, showed that nurses in units with higher staffing levels performed significantly more care activities, such as repositioning, feeding, bathing, oral care, and the number of assessments per shift. The omission of these activities is associated with the occurrence of pressure ulcers, falls, pneumonia, and supervision and control problems. The economic cost of care rationing has been estimated at approximately €700 per patient and additional day of hospital stay resulting from this phenomenon.59 Therefore, the results suggest that improved nursing staffing can reduce missed nursing care and, consequently, improve patient outcomes.60 This approach, which identifies missed care due to insufficient nursing staffing, has even validated instruments to assess its magnitude, such as the MISSCARE.58

Clinical practice environments and other staff outcomesThere are other elements besides nursing staffing that determine patient safety outcomes, such as the practice environment. Its influence, which is conceived as “the set of organisational attributes in the workplace that facilitate or hinder professional nursing practice,”61 has been shown to be associated with the emergence of AEs. Despite the complexity of its conceptualisation, the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI) has allowed its measurement with consistent results,62 but research has made available more than thirty instruments aimed at measuring this construct.63 It typically includes dimensions such as: 1) the nurse's autonomy in decision-making regarding patient care, 2) the nurse's participation in the decision-making bodies of their center, 3) the styles of collaborative relationships between medical and nursing staff, and 4) the adequacy of staffing or concern for the quality of care. In our country, it has been proven that in primary care, a practice environment perceived by nurses improves the control of patients with high blood pressure.64

Why are practice environments associated with better or worse nursing care outcomes?When these environments are inadequate, they can hinder the implementation of evidence-based safety interventions, exacerbating the gap between knowledge and practice, or leaving nurses without sufficient autonomy to develop their skills to their full potential. Furthermore, nurses often work under austere conditions, with increased care intensity and prioritising budgetary constraints over sustainable nursing service provision.66 This can lead to emotional stress, burnout, and higher turnover or intention to leave the job. There is also a significant correlation between nurses' age, burnout, and intention to leave the job, especially among those under 30 years of age.65,67,68

Furthermore, factors such as work shifts, overtime, shift length, the number of night shifts, and lack of adequate rest between shifts are associated with increased fatigue in nurses. For example, fatigue levels increase when nurses work more than 10 h in a single shift, which can compromise patient safety.69 Another dimension that affects the quality of care provided by nurses is job satisfaction, which has been widely studied. Job satisfaction refers to the comparison between the professional's current and ideal work situation. It is an integral part of the quality of care provided and has a direct impact on the outcomes of healthcare activities.70 In hospitals with a high patient-to-nurse ratio, nurses who perceive a poorer work environment show a greater intention to leave their jobs, which is closely related to job satisfaction.71 Conversely, high job satisfaction leads to a lower risk of stress-related illnesses, depression, anxiety, and burnout.72 The reasons why nurses may consider leaving their positions may also be linked to the interventions of their organisations' formal leaders and, therefore, potentially preventable. As nursing managers adopt transformational leadership behaviours, nurses are more likely to choose to remain in their positions.73

Methods based on stratification according to levels of care complexityCurrently the most innovative, these methods incorporate a clinical safety approach and assess the care needs and dependencies of individuals to identify care ISO complexity groups. They fall into two underlying subcategories: those that consider clinical components of care practice—those that share some approach to time-dependent methods—and those that focus on patient outcomes—methods that are far removed from time-dependent methods. It is very important to distinguish that care needs in these systems are derived from the characteristics of the individual, not from the activities and interventions deployed by the healthcare organisation.

As patient typologies become more complex, the importance of these systems becomes even more relevant. In the current context of complexity, where health systems face increasing challenges, particularly those stemming from an aging population and rising chronicity, this research plays a central role, with growing international efforts to translate this research into effective policies.26,74 Complex chronic patients suffer frequent admissions and are more exposed to the risks associated with hospitalisation, a relevant aspect for the quality and efficiency of health systems.75 There is solid evidence demonstrating how patient dependency and complexity levels influence health outcomes.76

However, the main problem lies in the conceptualisation of complexity, an issue that currently remains unresolved.

Complexity versus clinical components of healthcare practiceThe concept of complexity, expressed in terms such as: complex patient, complex case, complex care, complex practice, and complex needs, refers to both clinical challenges, such as therapeutic or procedural difficulty and the chronicity of the processes, and the impact of the disease and its treatment on the patient's daily life, as well as their personal and social circumstances. Therefore, the degree of complexity is determined by the instability, variability, and uncertainty inherent in the healthcare process.77,78

There is currently a profusion of proposals, instruments, and criteria for identifying patients with complex chronic conditions, making it very difficult to establish a gold standard to guide the development of health policies, the organisation of health services, and the management and evaluation of care based on these criteria. Many proposals focus on clinical components, which are not always the most explanatory from the perspective of the frequency and demand for health services, or on functional criteria, or with a moderate use of social and behavioural criteria. Thus, a review by Davis et al.79 identified 90 definitions of complex patients, which may also have different purposes: to stratify, segment, or identify target populations for interventions. Furthermore, a high use of subjective criteria was observed in the definitions and very different purposes, with a predominance of systems that seek to identify “hyper-utilising” patients, based on cost criteria (with extreme variability in the definition of utilisation), compared to others with a more predictive approach or others that seek to capture the presence of certain clinical or functional situations. Similarly, another review that attempted to bring together the elements comprising the definitions of complexity proposed to date80 identified 83 articles that defined patient complexity. Of these, it was defined according to clinical aspects in 36.1%, a classification tool was used in 43.4%, and a conceptual model was used in only 8.4% of cases.

Schaink et al.81 proposed the complexity framework more than a decade ago to synthesize the multiple perspectives that existed until then, although it did not cover the dimensions of frailty and disability. Zullig et al., proposed the complexity cycle model82 with six domains: 1) burden and effort of the person in carrying out ADLs, 2) acute clinical events, 3) accessibility and utilisation of health services, 4) patient preferences and expectations, and 5) interpersonal, organisational, and community factors. This proposal attempts to address conceptual gaps in previously proposed models, such as those by Shippe et al.,83 Safford et al.,84 Giovannetti et al.,85 Grembowski et al.,86 etc. Furthermore, there is considerable conceptual ambiguity in the use of other factors frequently associated with the need for care, such as frailty or vulnerability.87,88 For example, the causal relationship between frailty and multimorbidity continues to present many gaps.89 Ultimately, proposals for identifying complexity may have purposes other than the need for nursing care, and may be aimed solely at the likelihood of health service utilisation, or the need for activation or referral to certain levels of care, etc.

Therefore, although it is a very suggestive and logical approach, it is not easy to resolve the current conceptual labyrinth to identify, stratify, and segment the complexity of care required by a person.

An instrument that has been validated and disseminated in Spain for the purpose of identifying complexity is INTERMED.90 Originally designed to identify care needs upon admission of patients to acute hospitalisation, it classifies patient characteristics into four dimensions (biological, psychological, social, and health services) that generate a range of scores between 0 and 60. A cutoff point of 20–21 has been proposed to differentiate complexity in hospitalised patients.91 Its use has spread to many countries and settings, including primary care,92 although validation methods have often been disperse and have had significant limitations, particularly in sample size and the determination of construct and predictive validity.

Juvé et al., proposed the Care Complexity Index (CCFI),93 which differentiates hospitalised patients according to five domains: developmental, mental-cognitive, psychoemotional, sociocultural, and comorbidity/complications. It has been used to assess the onset of AEs,94 or the use of acute services.95

The Safer Nursing Care Tool (SNCT), recommended by NICE in the British NHS,96 is an instrument for managing nursing staff based on dependency and exacerbation levels, which has been linked to the occurrence of some AEs that are sensitive to nursing practice. The SNCT classifies patients into five levels and assigns a weighted multiplier to the number of nurses required according to each level. This is based on the observation of more than 40,000 episodes of care in the British NHS and has recently been tested in Canadian hospitals,97 and in South Korea.98 However, the instrument combines both clinical characteristics of patients and interventions performed (presence of oxygen therapy; chest drains; arterial blood gases; central catheterisations; tracheostomy; mechanical ventilation; neurological monitoring; vasoactive drugs, and need for vital signs monitoring) for stratification. This means that some of its indicators are subject to the already described potential bias of interinstitutional variability when establishing certain actions (e.g., the decision to initiate arterial blood gases or the frequency of vital signs taking in the same patient could be different depending on the hospital they are admitted to). An evaluation in the British NHS has shown a 3% reduction in mortality for each additional hour of nursing staffing99 (HR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.94–1.00), with mortality increasing when the rate of nurses on temporary contracts increased, although it was not able to identify a recommended cut-off threshold for the instrument.100

Complexity and nursing outcomes (NOC): a person-based outlookIn another methodological approach, the Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) has been proposed as a framework for developing research on health outcomes. It allows for the assessment of states, behaviours, or perceptions susceptible to nursing intervention, regardless of the institution in which the patient is admitted, as it only uses indicators of the patient's condition.101

Additionally, it has another advantage: its focus on outcomes sensitive to nursing practice, that is, those attributable to the presence or absence of an intervention on a previous health condition.102 Since 2006, research at INICIARE in Spain has been developing the design and validation of a tool based on these characteristics.103 After more than a decade, supported by several multicenter projects in 20 of the 28 hospitals of the Andalusian Public Health System, with different levels of complexity and management, and which have covered nearly 10,000 patients and more than 2000 professionals, the Level of Care Inventory through Nursing Outcomes Classification Indicators (INICIARE) instrument provides a structured evaluation format, developed from standardised nursing language and compatible with the digital clinical history, using a coding system included in the different health information systems1. INICIARE is based on a solid conceptual substrate, unlike many other proposals, with the capacity to describe a large number of phenomena and care situations.104 It has shown excellent reliability and internal consistency,104 with good construct validity in its short 26-item versión.105 It is an independent predictor of hospital mortality,76 has shown good acceptance for use by nurses in qualitative studies,106 and has been adapted to other settings such as Brazil.107 It is free of items related to nursing activities and is based on a conceptual approach that sought to avoid at all costs the inclusion of items derived from the actions of professionals, due to the institutional bias generated by the variability of practice styles and decision-making styles in identical clinical situations. Although this possibility was originally raised, during the statistical analysis, the difficulties encountered in validating items pertaining to nursing interventions forced them to be discarded in the internal consistency analysis phase.80 Except for the SNCT, neither INTERMED nor INICIARE have yet established indices for weighting nursing resources based on the identified level of care. However, in the case of INICIARE, it is at a maximum level of development. It has recently been evaluated in 6 countries in the Mediterranean basin (Italy, Greece, Lebanon, Egypt, Spain and Tunisia) on 20,000 users of hospital, primary and nursing home care108 and has also provided study on the incorporation of the latest advances in Machine Learning and intelligent models, which will enable the comparison of the distribution of nurses who care for patients with similar levels of dependency or care needs in different hospital.109

The origin of INICIARE stems from a practice setting conceived by care units not by diseases or medical specialities, the special unit or hospitalisation unit in the Alto Guadalquivir Hospital.80 As a result the research has been based on offering health services a tool that aids modernisation and adaptation of the convention hospitalisation units, in a reorganisation focused on care needs and care complexity.89

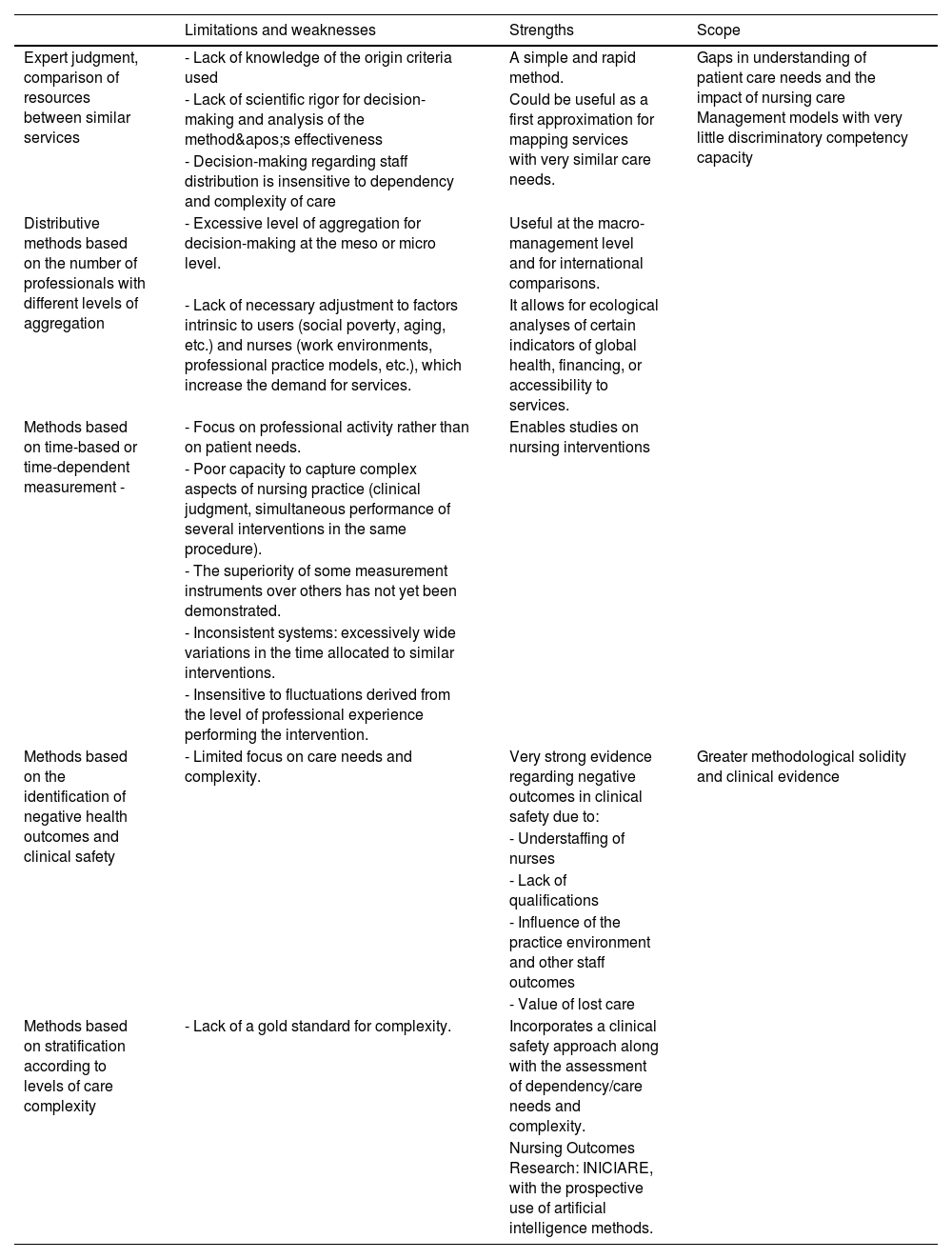

The leading certaintiesThe objective of this article has been to provide a description and review of the different approaches used to date in identification, including their advantages, scope, limitations, and potential future lines of research needed to address the remaining gaps (Table 1).

Limitations, weaknesses, strengths, and scope of methods for determining workforce adequacy.

| Limitations and weaknesses | Strengths | Scope | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expert judgment, comparison of resources between similar services | - Lack of knowledge of the origin criteria used | A simple and rapid method. | Gaps in understanding of patient care needs and the impact of nursing care Management models with very little discriminatory competency capacity |

| - Lack of scientific rigor for decision-making and analysis of the method's effectiveness | Could be useful as a first approximation for mapping services with very similar care needs. | ||

| - Decision-making regarding staff distribution is insensitive to dependency and complexity of care | |||

| Distributive methods based on the number of professionals with different levels of aggregation | - Excessive level of aggregation for decision-making at the meso or micro level. | Useful at the macro-management level and for international comparisons. | |

| - Lack of necessary adjustment to factors intrinsic to users (social poverty, aging, etc.) and nurses (work environments, professional practice models, etc.), which increase the demand for services. | It allows for ecological analyses of certain indicators of global health, financing, or accessibility to services. | ||

| Methods based on time-based or time-dependent measurement - | - Focus on professional activity rather than on patient needs. | Enables studies on nursing interventions | |

| - Poor capacity to capture complex aspects of nursing practice (clinical judgment, simultaneous performance of several interventions in the same procedure). | |||

| - The superiority of some measurement instruments over others has not yet been demonstrated. | |||

| - Inconsistent systems: excessively wide variations in the time allocated to similar interventions. | |||

| - Insensitive to fluctuations derived from the level of professional experience performing the intervention. | |||

| Methods based on the identification of negative health outcomes and clinical safety | - Limited focus on care needs and complexity. | Very strong evidence regarding negative outcomes in clinical safety due to: | Greater methodological solidity and clinical evidence |

| - Understaffing of nurses | |||

| - Lack of qualifications | |||

| - Influence of the practice environment and other staff outcomes | |||

| - Value of lost care | |||

| Methods based on stratification according to levels of care complexity | - Lack of a gold standard for complexity. | Incorporates a clinical safety approach along with the assessment of dependency/care needs and complexity. | |

| Nursing Outcomes Research: INICIARE, with the prospective use of artificial intelligence methods. |

Given the long list of approaches and proposals and the limitations of each, it might seem that after more than 70 years of research, we are at a dead end. However, this is not the case, and there are important certainties that must be systematically included in any nursing human resource planning.

Firstly, the causal association between staffing and the presence of negative health outcomes, especially in the hospital setting (much less evaluated in primary care), is solid evidence for this approach.1,18,33 This evidence is also accompanied by clear results regarding the economic return they represent, despite the investment in staffing increases. Therefore, any planning system must necessarily include monitoring of clinical safety linked to nursing staffing, an aspect that is currently not systematically guaranteed.31

Secondly, the fact that nurses do not possess the necessary competencies for their professional performance, and the increase in mortality or AEs in general, is undeniable evidence, which has been widely demonstrated in multiple countries, with samples and methods that dispel any doubt in this regard.54 Professional skills and competencies are necessary for excellent professional performance and patient safety.110 Therefore, it is unlikely that a nursing resource planning system, no matter how robust, can avoid the negative impact of management models with very little discriminatory competency capacity, or with the mass mobilisation of large numbers of nurses regardless of their competency level. Temporary hiring systems, public job offers, transfer competitions, and other common selection processes in Health Systems, together with the poor regulation of specialist nurse positions in many autonomous communities,111 can therefore seriously jeopardize the skill mix of nurses working in a unit or centre, especially during vacation periods, when the frequent presence of shifts in which nurses lack sufficient clinical experience in highly complex care settings is well known and reported. Similarly, following a transfer competition, it is highly common in primary care for health centres to end up losing a critical mass of specialist nurses or those with extensive experience in this setting, with the consequent impact on care programs and the service portfolio.

Thirdly, s it is vital to understand the joint interaction with other factors such as the practice environment, job satisfaction, nurses' experience, and the potential temporality of their assignment to the units. It is striking that policymakers and planners repeatedly ignore this evidence and continue to maintain situations of clear understaffing of nurses, with the resulting impact on clinical safety and on nurses' mental health and job satisfaction.112

Fourthly, systems based on patient characteristics and circumstances, focused on identifying care needs based on complexity, are those that offer the greatest methodological robustness. This is due both to their ability to classify patients without the bias of institutional variability and to the theoretical foundation on which some of them are based, supported by the measurement of outcomes sensitive to nursing practice that affect clinical safety.104

Finally, in the context of the complexity of health systems and the heterogeneity of patient profiles, simplistic responses based on averages are not feasible for estimating reliable measures applicable to any type of professional environment. Quantifying variations in practice contexts is extremely difficult, and certain situations, such as intensification of care, patient turnover, and the experience and attitude of the professional, may be beyond control. Ignoring these contextual factors will yield biased and inconsistent assessments, regardless of the precision and validity of the models for measuring complexity and calculating the necessary staff.113

ForesightThe extensive scientific evidence in this field provides a solid justification for the implementation of these policies. As healthcare faces the challenge of patients with more complex needs, it is essential to have sufficient nurses to provide high-quality care. Although it may seem paradoxical, the financial constraints faced by many healthcare systems can also facilitate the adoption of healthcare policies that increase staffing. Implementing nurse-patient ratio policies can lead to greater efficiency in resource utilisation. For example, by reducing readmission rates, complications, and errors, these policies can generate significant long-term savings.

Other elements that can provide significant assistance are the use of big data-based analytical models. Thanks to the vast availability of records in electronic medical records the opportunity for refining these models is highly promising.

The methodological challenge of developing a valid, reliable, robust, and consistent method for planning nurse-patient ratios is complex but knowledge is showing us where our efforts should be directed and the consequences of ignoring this. The paradox is that we are continuing to organise the human resources structure for the provision of nursing services using the same methods as those used at the end of the 20th century.

ConclusionsThe most logical proposal based on the knowledge available today, would be a model that stratifies levels of patient complexity, based on care dependency, with minimal presence of indicators that may be subject to inter-institutional variability. These should also be linked to outcomes sensitive to nursing practice and clinical safety, and should take into account contextual factors such as the practice setting, the competency mix of nurses, and staff seasonality and turnover. Finally, these approaches need to be extended to the management of nursing human resources in the context of primary care and also in social and healthcare, where research on these aspects is much more limited.