To compare techniques to analyze the content validity of measurement instruments applicable to nursing care research through a practical case.

MethodSecondary study derived from validating the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety (HSOPS) in a Chilean hospital. The study setting was hospital care, with a population focused on nursing staff and a sample of 12 expert nurses who are teachers or have clinical experience in quality and patient safety. Design and content validity test based on three phases: identification of primary methods, calculation of methods, comparison of similarities and differences of methods.

ResultsLawsche, Tristan-López, Lynn, Polit et al. methods are similar. The modified kappa value is similar to the content validity index (I-CVI) value, with a slight variation when penalizing the value by probability according to chance. There are significant differences between all methods and Hernández Nieto’s content validity coefficient (CVC).

ConclusionsThe Polit et al. method is more rigorous, and its mathematical formulation is better justified, providing solidity to clinical nursing research. Furthermore, the Hernandez-Nieto method is suggested when validating more than one characteristic.

Comparar diferentes técnicas para analizar la validez de contenido de instrumentos de medición aplicables en la investigación en cuidados de enfermería a través de un caso práctico.

MétodoEstudio secundario que deriva de la validación de una encuesta hospitalaria sobre seguridad del paciente (HSOPS) en un hospital chileno. El ámbito de estudio fue la atención hospitalaria, con una población centrada en el personal de enfermería y una muestra de 12 expertas enfermeras docentes o con experiencia clínica en calidad y seguridad del paciente. Diseño y prueba de validez de contenido basado en tres fases: identificación de principales métodos, cálculo de los métodos, comparación similitudes y diferencias de los métodos.

ResultadosExiste similitud entre los métodos de Lawsche, Lawsche-Tristan, Lynn, Polit et al. El valor kappa modificado es similar al valor de Índice de Validez de Contenido (I-CVI), con una pequeña variación que se produce al penalizar el valor por probabilidad de acuerdo al azar. Existen diferencias significativas entre todos los métodos y el Coeficiente de Validez de Contenido (CVC) de Hernández Nieto.

ConclusionesEl método de Polit et al. tiene mayor rigor y su formulación matemática está mejor justificada, entregando solidez a la investigación en enfermería clínica. Además, se sugiere utilizar el método de Hernandez-Nieto cuando se busca validar más de una característica.

Content validity is a fundamental property of measurement instruments, and there are different techniques for analysing it.

What this study contributes to nursing researchThe study provides the first detailed comparison of five techniques for analysing content validity. This description enables nursing professionals to improve their choice of content validation assessment method for questionnaires used in clinical practice.

Nursing research is essential for improving both the quality of the nursing team management and the delivery of care. Validated and reliable questionnaires, surveys, or measurement instruments are frequently used for this purpose. In clinical nursing, it is essential to have precise instruments that guarantee what is intended to be measured.1

The Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) taxonomy considers content validity to be the most important measurement property and recommends assessing content validity using proposed standards for relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility. It offers a checklist to ensure a systematic and transparent evaluation of the content validation of measurement instruments.2

There are content validation methods that involve one or two rounds of expert judgment and statistical analysis. Expert judgment analysis involves selecting a panel of experts in the subject area who assess the relevance and representativeness of each item in the instrument. It consists of the following stages: 1. Expert selection: Experts must have in-depth knowledge and experience in the instrument's subject area; 2. Item evaluation: Each expert reviews the instrument's items and rates their relevance using a scale (e.g., 1 to 4, where 1 is “not relevant” and 4 is “very relevant”); 3. Results analysis: The level of agreement among experts is calculated, for example, by averaging the relevance ratings for each item, and determining whether the items meet the predefined threshold of acceptability.

In nursing, various instruments are used to assess aspects such as quality of life and patient safety. Given the widespread use of measurement instruments in clinical nursing, the importance of content validity, and the lack of similar previous studies, it was considered relevant to compare different techniques for studying content validity using a practical case study, with the aim of providing rigour to nursing care research. In this context, the objective of this study was to compare different techniques for analysing the content validity of measurement instruments applicable to nursing care research using a practical case study.

MethodA secondary study derived from the validation of a hospital-based survey on patient safety (HSOPS) in a Chilean hospital.3 The analysis included three phases: 1) identification of the main methods for assessing content validity; 2) calculation according to each method; and 3) differences and similarities between the methods.

The setting was a high-complexity hospital in Valparaíso, Chile, based on primary research conducted in 2021.3 The population consisted of 12 experts: six academic nurses with a master's degree and five years of teaching experience in healthcare management or research, and six nurses with five years of experience in the hospital's quality management and patient safety units.

The variables corresponded to the level of sufficiency, clarity, coherence, and relevance assigned by each expert for each item. A score was obtained based on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4, with 1 being irrelevant and 4 being extremely relevant.

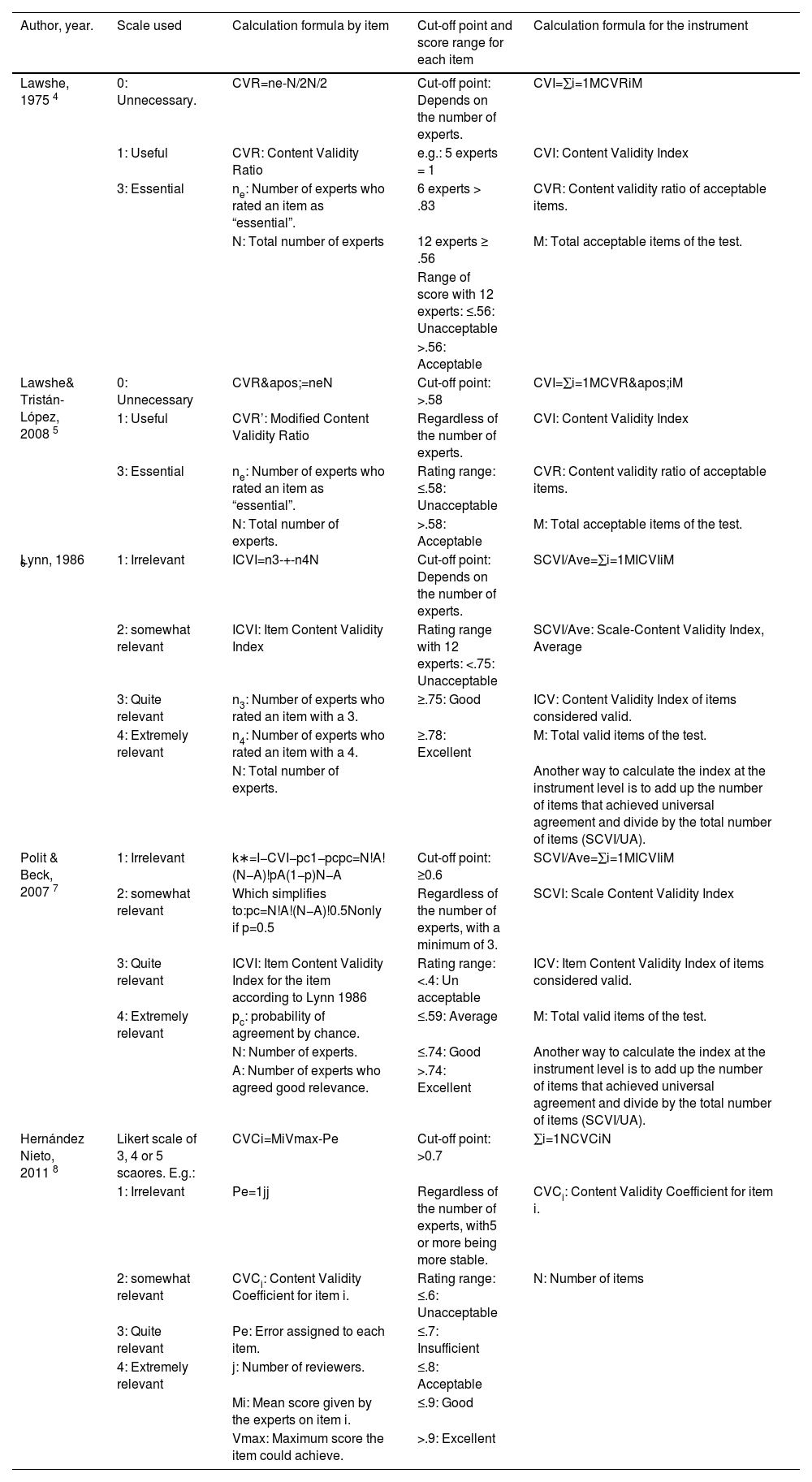

Data collection was carried out by email to each expert. Two rounds were conducted to achieve ACCEPTABLE levels of content validity. The five techniques compared to identify differences and similarities were Lawshe,4 Lawshe & Tristán-López,5 Lynn,6 Polit & Beck,7 and Hernández Nieto,8 as described in Table 1. These techniques are primarily proportional, based on the sum of experts who rated the item positively over the total number of experts. Lawshe proposes an index (similar to a correlation) that ranges from −1 to 1. On a three-value scale, the calculation considers the number of experts who rate the item as essential.

Description of content validity methods, including the scale used and the calculation formula.

| Author, year. | Scale used | Calculation formula by item | Cut-off point and score range for each item | Calculation formula for the instrument |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lawshe, 1975 4 | 0: Unnecessary. | CVR=ne-N/2N/2 | Cut-off point: Depends on the number of experts. | CVI=∑i=1MCVRiM |

| 1: Useful | CVR: Content Validity Ratio | e.g.: 5 experts = 1 | CVI: Content Validity Index | |

| 3: Essential | ne: Number of experts who rated an item as “essential”. | 6 experts > .83 | CVR: Content validity ratio of acceptable items. | |

| N: Total number of experts | 12 experts ≥ .56 | M: Total acceptable items of the test. | ||

| Range of score with 12 experts: ≤.56: Unacceptable | ||||

| >.56: Acceptable | ||||

| Lawshe& Tristán-López, 2008 5 | 0: Unnecessary | CVR'=neN | Cut-off point: >.58 | CVI=∑i=1MCVR'iM |

| 1: Useful | CVR’: Modified Content Validity Ratio | Regardless of the number of experts. | CVI: Content Validity Index | |

| 3: Essential | ne: Number of experts who rated an item as “essential”. | Rating range: ≤.58: Unacceptable | CVR: Content validity ratio of acceptable items. | |

| N: Total number of experts. | >.58: Acceptable | M: Total acceptable items of the test. | ||

| Lynn, 1986 6 | 1: Irrelevant | ICVI=n3-+-n4N | Cut-off point: Depends on the number of experts. | SCVI/Ave=∑i=1MICVIiM |

| 2: somewhat relevant | ICVI: Item Content Validity Index | Rating range with 12 experts: <.75: Unacceptable | SCVI/Ave: Scale-Content Validity Index, Average | |

| 3: Quite relevant | n3: Number of experts who rated an item with a 3. | ≥.75: Good | ICV: Content Validity Index of items considered valid. | |

| 4: Extremely relevant | n4: Number of experts who rated an item with a 4. | ≥.78: Excellent | M: Total valid items of the test. | |

| N: Total number of experts. | Another way to calculate the index at the instrument level is to add up the number of items that achieved universal agreement and divide by the total number of items (SCVI/UA). | |||

| Polit & Beck, 2007 7 | 1: Irrelevant | k∗=I−CVI−pc1−pcpc=N!A!(N−A)!pA(1−p)N−A | Cut-off point: ≥0.6 | SCVI/Ave=∑i=1MICVIiM |

| 2: somewhat relevant | Which simplifies to:pc=N!A!(N−A)!0.5Nonly if p=0.5 | Regardless of the number of experts, with a minimum of 3. | SCVI: Scale Content Validity Index | |

| 3: Quite relevant | ICVI: Item Content Validity Index for the item according to Lynn 1986 | Rating range: <.4: Un acceptable | ICV: Item Content Validity Index of items considered valid. | |

| 4: Extremely relevant | pc: probability of agreement by chance. | ≤.59: Average | M: Total valid items of the test. | |

| N: Number of experts. | ≤.74: Good | Another way to calculate the index at the instrument level is to add up the number of items that achieved universal agreement and divide by the total number of items (SCVI/UA). | ||

| A: Number of experts who agreed good relevance. | >.74: Excellent | |||

| Hernández Nieto, 2011 8 | Likert scale of 3, 4 or 5 scaores. E.g.: | CVCi=MiVmax-Pe | Cut-off point: >0.7 | ∑i=1NCVCiN |

| 1: Irrelevant | Pe=1jj | Regardless of the number of experts, with5 or more being more stable. | CVCi: Content Validity Coefficient for item i. | |

| 2: somewhat relevant | CVCi: Content Validity Coefficient for item i. | Rating range: ≤.6: Unacceptable | N: Number of items | |

| 3: Quite relevant | Pe: Error assigned to each item. | ≤.7: Insufficient | ||

| 4: Extremely relevant | j: Number of reviewers. | ≤.8: Acceptable | ||

| Mi: Mean score given by the experts on item i. | ≤.9: Good | |||

| Vmax: Maximum score the item could achieve. | >.9: Excellent |

Lawshe, modified by Tristán, simplifies the previous method by using the proportion of the total number of experts who rated an item as essential over the total number of experts. This makes the method easier to interpret, ranging from 0 to 1.

Lynn estimates the content validity index (I-CVI) and measures the proportion of experts who rate an item as “fairly or extremely relevant” out of the total number of experts. This is very similar to the previous method, except that the scale used is a 4-value scale, not a 3-value scale.

Polit and Beck propose a correction to the previous index with the modified Kappa, calculating the probability of agreement by chance to subtract it from the I-CVI value, thereby ensuring the reduction of any statistical distortion.

Hernandez Nieto measures the ratio obtained between the mean scores assigned to the item and the maximum score that can be obtained as a rating for that item. This is interpreted as the “level of achievement” achieved. It also corrects for the statistical error assigned to each item, which is a constant. When multiple dimensions are assessed, the calculation is performed by adding together the four dimensions for each item and not individually for each dimension. Additionally, the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to evaluate overall differences between the method distributions, and Dunn's post hoc test was used to identify method pairs with significant differences.

Ethical considerationsThe study was part of a project approved by the Deontological Commission of the Universitat Jaume I, File CD/43/2019. The ethical considerations set forth in Law 20.585 on access to public information in Chile and the principles of the Helsinki Declaration were adhered to. The expert evaluators electronically signed the informed consent form, with prior clarification that their participation was voluntary and anonymous.

ResultsThe results obtained for the “relevance” characteristic for each item and the average for each dimension of the HSOPS 2.0 instrument during the cross-cultural adaptation process are presented in Table 2.

Summary of validity indices for each item. The lowest values are highlighted in bold.

| LAWSCHE | LAWSCHE TRISTAN | LYNN | POLIT & BECK | HERNANDEZ NIETO | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIM | ITEM | CVR | Rating | CVR' | Rating | ICV | Rating | K* | Rating | CVC | Rating |

| D1 | 1 (A1) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9479 | EXCELLENT |

| D1 | 2 (A8) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9635 | EXCELLENT |

| D1 | 3 (A9) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9844 | EXCELLENT |

| D2 | 4 (A2) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9219 | EXCELLENT |

| D2 | 5 (A3) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .8958 | BUENA |

| D2 | 6 (A5) | .8333 | ACCEPTABLE | .9167 | ACCEPTABLE | .9167 | EXCELLENT | .9164 | EXCELLENT | .9115 | EXCELLENT |

| D2 | 7 (A11) | .6667 | ACCEPTABLE | .8333 | ACCEPTABLE | .8333 | EXCELLENT | .8306 | EXCELLENT | .8906 | BUENA |

| D3 | 8 (A4) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9792 | EXCELLENT |

| D3 | 9 (A12) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9687 | EXCELLENT |

| D3 | 10 (A14) | .8333 | ACCEPTABLE | .9167 | ACCEPTABLE | .9167 | EXCELLENT | .9164 | EXCELLENT | .9323 | EXCELLENT |

| D4 | 11 (A6) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9583 | EXCELLENT |

| D4 | 12 (A7) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9792 | EXCELLENT |

| D4 | 13 (A10) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9792 | EXCELLENT |

| D4 | 14 (A13) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9635 | EXCELLENT |

| D5 | 15 (B1) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9844 | EXCELLENT |

| D5 | 16 (B2) | .8333 | ACCEPTABLE | .9167 | ACCEPTABLE | .9167 | EXCELLENT | .9164 | EXCELLENT | .9427 | EXCELLENT |

| D5 | 17 (B3) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9740 | EXCELLENT |

| D6 | 18 (C1) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9792 | EXCELLENT |

| D6 | 19 (C2) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9844 | EXCELLENT |

| D6 | 20 (C3) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9740 | EXCELLENT |

| D7 | 21 (C4) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9896 | EXCELLENT |

| D7 | 22 (C5) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9844 | EXCELLENT |

| D7 | 23 (C6) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9844 | EXCELLENT |

| D7 | 24 (C7) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9948 | EXCELLENT |

| D8 | 25 (D1) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9062 | EXCELLENT |

| D8 | 26 (D2) | .8333 | ACCEPTABLE | .9167 | ACCEPTABLE | .9167 | EXCELLENT | .9164 | EXCELLENT | .8698 | GOOD |

| D9 | 27 (F1) | .8333 | ACCEPTABLE | .9167 | ACCEPTABLE | .9167 | EXCELLENT | .9164 | EXCELLENT | .9271 | EXCELLENT |

| D9 | 28 (F2) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9844 | EXCELLENT |

| D9 | 29 (F3) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9635 | EXCELLENT |

| D10 | 30 (F4) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9427 | EXCELLENT |

| D10 | 31 (F5) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9062 | EXCELLENT |

| D10 | 32 (F6) | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9687 | EXCELLENT |

| TOTAL AVERAGE | .9635 | ACCEPTABLE | .9818 | ACCEPTABLE | .9818 | EXCELLENT | .9816 | EXCELLENT | .9543 | EXCELLENT | |

| DIM1 Average | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9653 | EXCELLENT | |

| DIM2 Average | .875 | ACCEPTABLE | .9375 | ACCEPTABLE | .9375 | EXCELLENT | .9368 | EXCELLENT | .9049 | EXCELLENT | |

| DIM3 Average | .9444 | ACCEPTABLE | .9722 | ACCEPTABLE | .9722 | EXCELLENT | .9721 | EXCELLENT | .9601 | EXCELLENT | |

| DIM4 Average | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9701 | EXCELLENT | |

| DIM5 Average | .9444 | ACCEPTABLE | .9722 | ACCEPTABLE | .9722 | EXCELLENT | .9721 | EXCELLENT | .9670 | EXCELLENT | |

| DIM6 Average | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9792 | EXCELLENT | |

| DIM7 Average | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9883 | EXCELLENT | |

| DIM8 Average | .9167 | ACCEPTABLE | .9583 | ACCEPTABLE | .9583 | EXCELLENT | .9582 | EXCELLENT | .8880 | EXCELLENT | |

| DIM9 Average | .9444 | ACCEPTABLE | .9722 | ACCEPTABLE | .9722 | EXCELLENT | .9721 | EXCELLENT | .9583 | EXCELLENT | |

| DIM10 Average | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | ACCEPTABLE | 1 | EXCELLENT | 1 | EXCELLENT | .9392 | EXCELLENT | |

CVC: Content Validity Coefficient; CVR: Content Validity Ratio; DIM: Instrument Dimension; ICVI: Item Content Validity Index; K*: Modified Kappa.

Similarity is observed between the Lawsche, Lawsche-Tristan, Lynn, and Polit & Beck methods, as 81.25% of the items (n = 21) obtained values equal to 1. The Lawshe and Lawshe-Tristan values are practically the same, but on a different scale. The Lawsche-Tristan and Lynn values are the same due to the way the data were grouped to be consistent with the Lawsche-Tristan three-value scale. In the case presented, values 3 and 4 of the scale were combined. This procedure is the same as that used by Lynn's method to calculate the I-CVI. The modified Kappa value was found to be similar to the I-CVI value, with a slight downward shift, which occurs as the value obtained decreases due to the probability of agreement with chance.

The Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post hoc test identified that the CVC variable has significantly different distributions compared to CVR, CVR', I-CVI, and K* (p < .001).

In none of the methods applied were items eliminated when they obtained values below the acceptance threshold defined for each one (see Table 1). The supplementary material details the calculation and characteristics such as adequacy, clarity, and consistency.

DiscussionUsing a practical case, five techniques for analysing the content validity of measurement instruments applicable to nursing care research were compared. It is important to identify the most appropriate way to calculate the content validity index, depending on the problem being addressed and the type of instrument being validated.9 The values obtained were high, and there were no significant differences between the methods applied, due to the instrument having undergone a prior validation process which facilitated item selection even though it was in another language. The selection of experts was essential, including determining the criteria for their selection; their quantity; the rating process that includes a reminder, and the estimated timeframe for this.10

The first four techniques were similar, and the most optimal was Polit & Beck, due to its accurate collection of information. The differences in the I-CVI values could be due to the nature of the calculation, since none of them received the maximum score. The items that did not obtain an “Excellent” rating coincide with low ratings from other methods, which could be due to the fact that they used characteristics other than relevance. In this sense, the Hernandez-Nieto method (CVC) presented greater differences and provided complementary information for the analysis. This difference was confirmed to be significant through statistical analysis using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post hoc test.

This study is not without methodological limitations, such as using a single measurement instrument, with a narrow range of experts, and in a specific geographical context. Furthermore, the topic was approached from a case study rather than synthetic data. These limitations should be taken into account in future research. However, we believe that this study provides relevant results on different techniques for studying content validity.

In conclusion, the use of the Polit & Beck method for content validity in measurement instruments for clinical nursing research is recommended because it is more mathematically rigorous and more highly justified, providing solid support for research in care. Additionally, the Hernandez-Nieto method is recommended when validating more than one characteristic.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific support from the public, private, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We are grateful for the participation of the expert panel, comprised of academic nurses and clinical nurses with experience in quality management and patient safety in Chile.