The VINCat Program: a 19-year model of success in infection prevention and control of healthcare-associated infections in Catalonia, Spain

More infoHand hygiene is regarded as the cornerstone for preventing healthcare-associated infections. This study assesses trends in alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) consumption for hand hygiene and availability of dispensers at the point of care (POC) in acute care hospitals in Catalonia, as part of the VINCat program.

MethodsData were collected from 2014 to 2022 in 69 hospitals, categorized by size and type, including large, medium, small, and specialized facilities. ABHR consumption was measured in liters per 1000 patient-days, with data segmented into intensive care units (ICUs) and non-ICU wards. Hospital infection control personnel determined the availability of ABHR solutions at the POC through yearly point prevalence surveys.

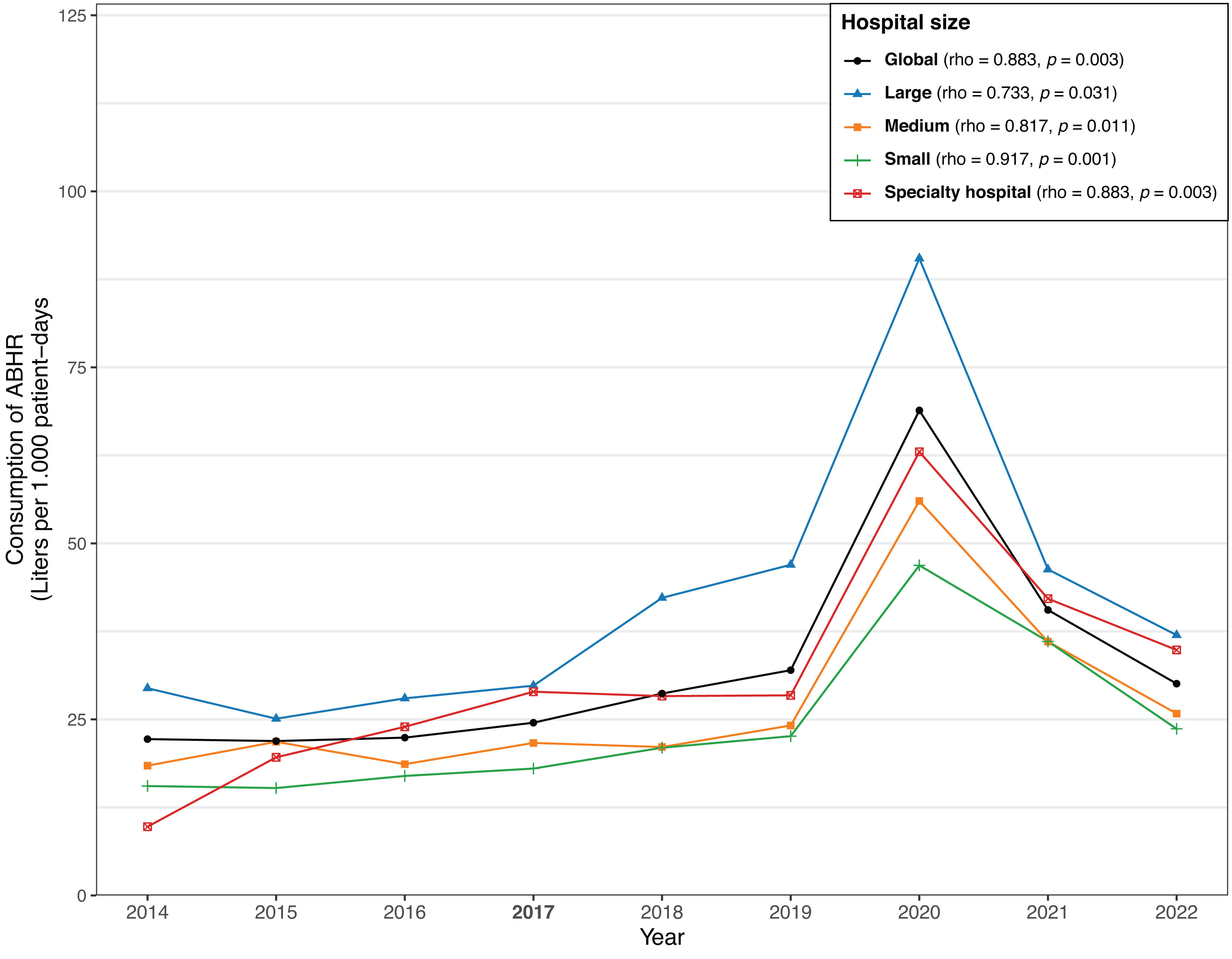

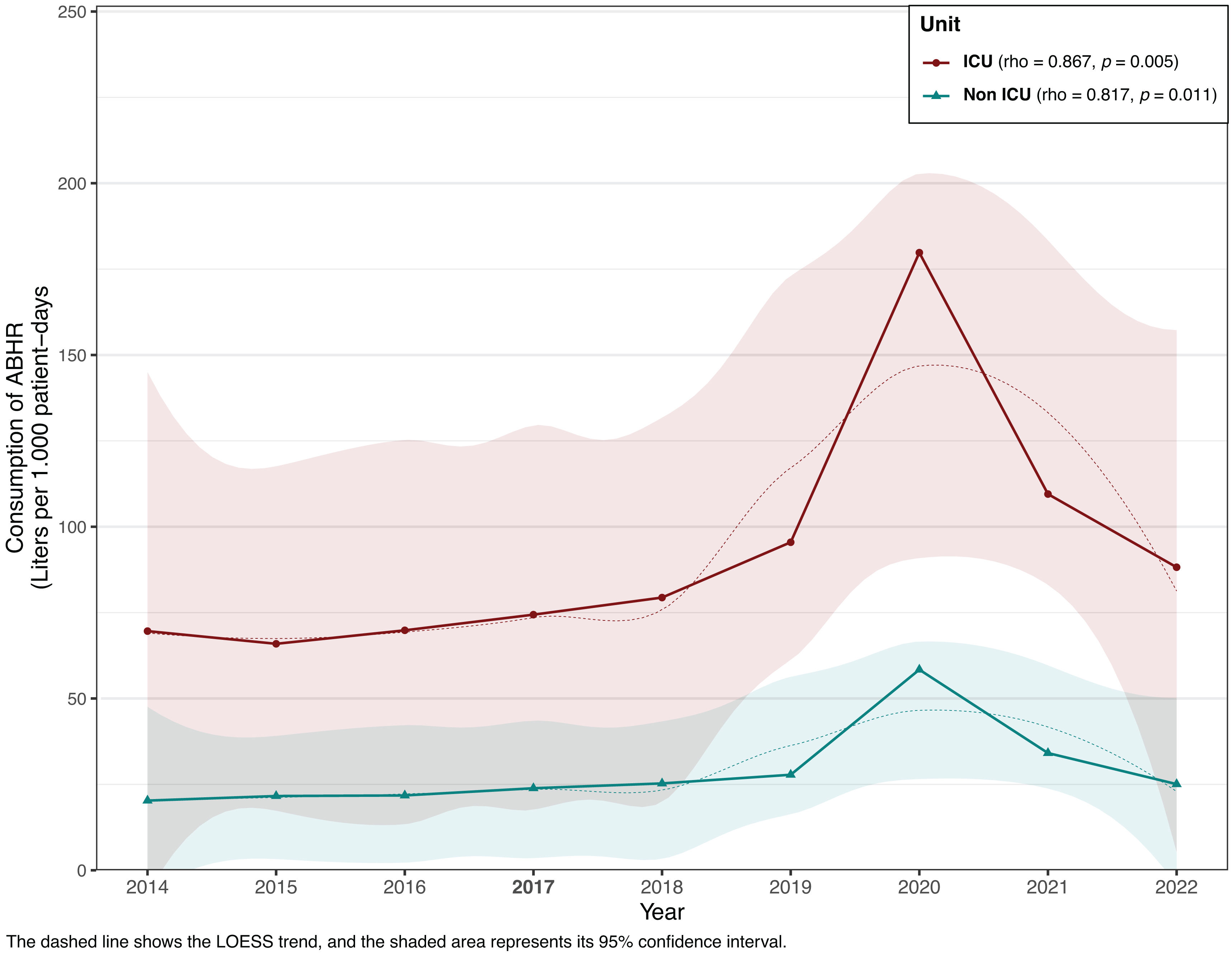

ResultsThe study found a significant increase in ABHR consumption over time, with usage rising from 22.8L/1000 patient-days in the 2014–2017 period to 39.9L in 2018–2022, representing a 75% increase. The most significant growth was observed in ICUs, where ABHR use nearly doubled. ABHR consumption also spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, with large hospitals showing the highest levels of usage. Additionally, the availability of ABHR dispensers at the POC increased, particularly in non-ICU wards and small hospitals.

ConclusionsThe findings underscore the role of sustained hand hygiene efforts, including increased ABHR availability at the POC, as essential components of infection prevention. These efforts are especially crucial in high-risk units such as ICUs and in smaller hospitals, where resources and compliance may be limited.

La higiene de manos se considera la piedra angular de la prevención de las infecciones relacionadas con la atención sanitaria. Este estudio evalúa las tendencias en el consumo de soluciones hidroalcohólicas (SHA) y la disponibilidad de dispensadores en el punto de atención (PA) en los hospitales de atención aguda en Cataluña, como parte del programa VINCat.

MétodosSe recopilaron datos de 2014 a 2022 en 69 hospitales, categorizados por tamaño y tipo, incluyendo grandes, medianos, pequeños y especializados. El consumo de SHA se midió en litros por cada 1.000 días de estancia, con datos segmentados entre unidades de cuidados intensivos (UCI) y no UCI. La disponibilidad de SHA en el PA se determinó mediante encuestas anuales de prevalencia.

ResultadosSe observó un incremento significativo en el consumo de SHA de 22,8 l por cada 1.000 días de estancia en el período 2014-2017 a 39,9 l en 2018-2022 (incremento del 75%). El mayor aumento se observó en las UCI, donde el uso de SHA casi se duplicó. El consumo de SHA también aumentó considerablemente durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en 2020, con los hospitales grandes mostrando los niveles más altos de uso. Además, la disponibilidad de dispensadores de SHA en el PA aumentó, especialmente en las no UCI y en hospitales pequeños.

ConclusionesLos hallazgos subrayan la importancia de mantener los esfuerzos en higiene de manos, especialmente en los entornos de alto riesgo y en los hospitales más pequeños, donde los recursos y el cumplimiento pueden ser limitados.

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are infections acquired within healthcare settings, often due to invasive procedures performed during patient care.1 These infections represent a significant threat to patient safety, ranking among the most common adverse events in healthcare.2 Additionally, many of these infections are caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) microorganisms, which pose a significant concern due to their potential for spread and the limited treatment options available.3 The impact of HAIs extends beyond patient safety, contributing to increased morbidity and mortality rates, diminished quality of life, and escalating healthcare costs. As a result, HAIs place a substantial burden on healthcare systems worldwide.4

The 2022 Global Report on Infection Prevention and Control by the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that between 7% and 10% of patients will acquire an HAI during their hospital stay.5 In Catalonia, data from the VINCAT program surveillance system revealed a prevalence of 7.10% of HAIs in acute care hospitals in 2022.6 Considering the nearly 19,000 hospital acute care beds, this figure suggests that thousands of patients are affected by HAIs each year in our region alone.

Notably, the WHO report emphasizes that effective and cost-efficient practices can prevent up to 70% of HAIs. Hand hygiene is considered the cornerstone of HAI prevention and is recognized as the most effective measure to reduce transmission. In 2009, the WHO introduced its “Five Moments” model for hand hygiene, specifically aimed at minimizing the risk of microorganism transmission in hospitals.7 To promote compliance with hand hygiene among healthcare professionals, the WHO recommends implementing multimodal strategies, which include (1) system change through the introduction of alcohol-based hand rubs (ABHR), (2) training and education, (3) evaluation and feedback, (4) reminders in the workplace, and (5) the creation of a safety climate. Moreover, ABHR consumption is a valuable surrogate parameter for hand hygiene performance and can be easily tracked in the healthcare setting.8

A vital component of these strategies is ensuring that ABHR is readily available and accessible at the point of care (POC), where the patient, healthcare worker, and care intersect.9 The placement of ABHR dispensers is critical in promoting hand hygiene practices and improving compliance. Studies have shown that the strategic placement of dispensers can significantly impact compliance rates more than the mere quantity of dispensers available.10 Nonetheless, sustained improvement in hand hygiene compliance requires implementing comprehensive multimodal strategies, where easy access to ABHR is a key aspect of the system change component of the multimodal strategy recommended by the WHO.

This study aims to assess trends in ABHR consumption from 2014 to 2022 and evaluate the availability of ABHR solutions at the POC in acute care hospitals in Catalonia. By analyzing data from the VINCat program, we seek to understand the impact of these efforts on improving hand hygiene compliance and infection prevention practices across different hospital settings.

MethodsThe VINCat program, established in 2006 as the infection prevention and control program of HAIs by the Catalan Department of Health, has monitored hand hygiene compliance in Catalan hospitals since 2014.11 Specifically, the program tracks ABHR consumption and availability of dispensers at the POC as indirect indicators of hand hygiene adherence.

ABHR consumption: ABHR consumption was calculated using liters per 1000 patient-days. Leading hospital infection control personnel provided retrospective yearly data on ABHR consumption in each participating hospital from 2014 to 2022. A total of sixty-nine hospitals contributed to the study. Hospitals were categorized by size as follows: large university hospitals (>500 beds, 9 centers), medium hospitals (200–500 beds,18 centers), small hospitals (<200 beds, 37 centers), and specialized hospitals (three oncologic, one urologic, one neurorehabilitation centers). Data were collected annually from each hospital and segmented into two main categories, intensive care units (ICUs) and medical or surgical wards, and compared in two distinct periods: Period 1 (2014–2017) and Period 2 (2018–2022). The hospital infection control personnel determined the availability of ABHR solutions at the POC through yearly point prevalence surveys. Adequate POC for ABHR solutions was developed in a consensus document between the VINCat HM group and the Catalan Association for Infection Control (ACICI) and12 was standardized through VINCat hospitals and considered correct when located less than 2m away from the patient's bed, visible and accessible without barriers or elements that hinder or prevent access.

Ethical issuesThe study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, with international human rights considerations, and with the legislation regulating biomedicine and personal data protection. All data were treated as confidential, and records were accessed anonymously. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bellvitge Hospital (Ref. PR066/18). Patient data were anonymized, so the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research waived the requirement for informed consent.

Statistical analysisABHR consumption was calculated as an incidence rate, expressed in liters per 1000 patient-days. The availability of ABHR dispensers at the POC was reported as a percentage of hospital beds equipped with dispensers. Differences in dispenser prevalence between the two study periods (2014–2017 and 2018–2022) were analyzed using the chi-square test. Crude incidence rate ratios (cIRRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to compare ABHR consumption between the two periods. To evaluate the strength and direction of the monotonic relationship between ABHR consumption and the availability of ABHR dispensers at the POC over the years, we performed a Spearman correlation (rho). LOESS smoothing was applied to graphs to better illustrate trends over time in both intensive care units (ICUs) and non-ICU wards.

A significance level of 0.05 was applied to all statistical tests. The results were analyzed using the R statistical software version 4.2.2, developed by The R Foundation in Vienna, Austria.

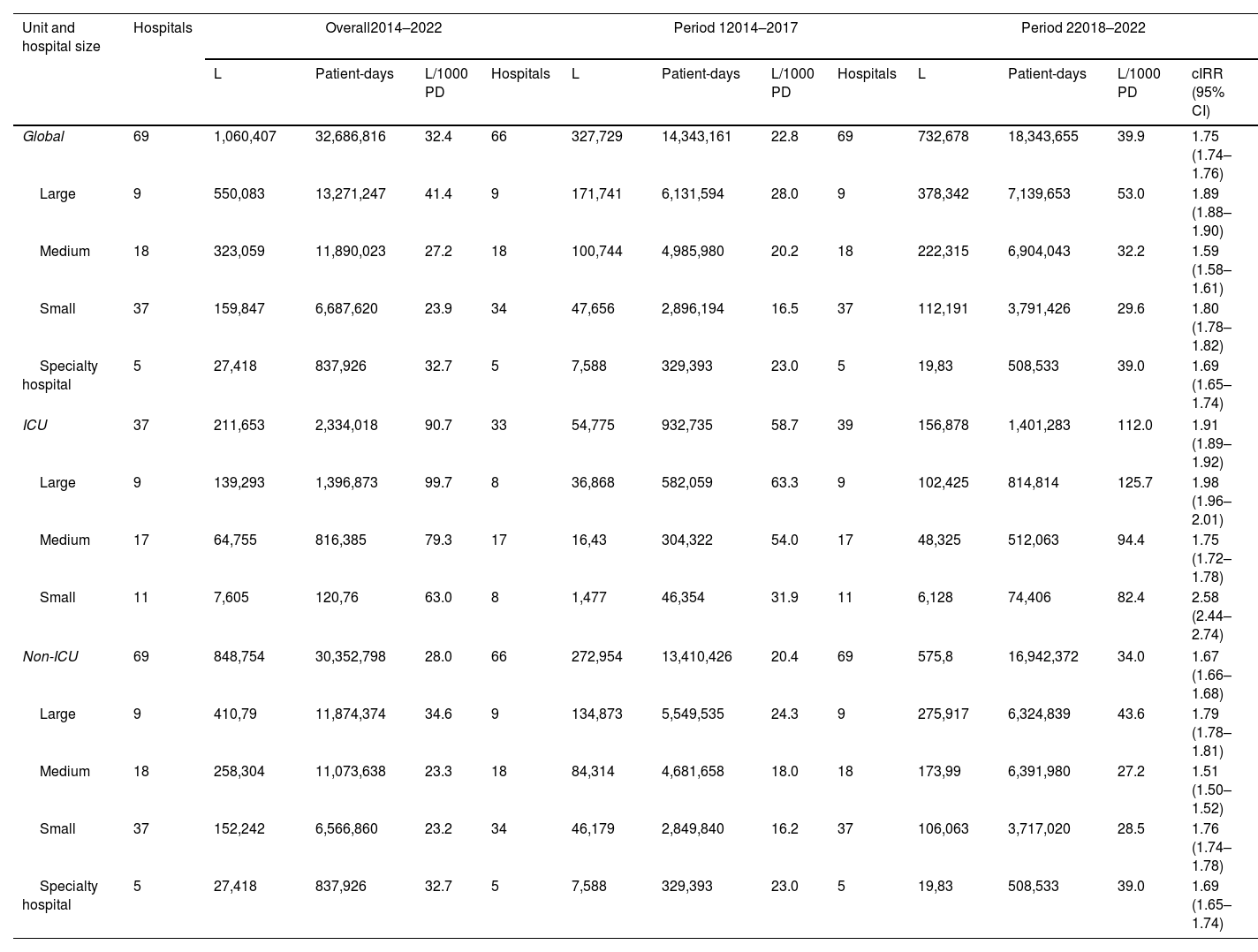

ResultsData on ABHR consumption across different types of hospitals and periods is shown in Table 1. Over the entire study period (2014–2022), the overall consumption was 32.4L/1000 patient-days, with significantly higher usage in ICUs (90.7L/1000 patient-days) compared to non-ICU wards (28.0L/1000 patient-days). Important variations were observed between hospital types. Large hospitals had the highest ABHR consumption (41.4L/1000 patient-days), followed by specialty hospitals (31.7L/1000 patient-days) compared to lower consumption in medium and small hospitals. Overall consumption increased from 22.8L/1000 patient-days in Period 1 to 39.9L/1000 patient-days in Period 2 (incidence rate ratio (IRR): 1.75 (95% CI: 1.74–1.76), indicating a 75% increase in ABHR use between the two periods. The higher increase between the two periods was observed in ICUs where ABHR use rose from 58.7L/1000 patient-days to 112.0L/1000 patient-days (IRR 1.91). The ICUs from large hospitals showed the highest usage increase from 63.3L/1000 patient-days in Period 1 to 125.7L/1000 patient-days in Period 2 (IRR 1.98) and almost doubled their consumption.

Trends in alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) consumption (liters per 1000 patient-days).

| Unit and hospital size | Hospitals | Overall2014–2022 | Period 12014–2017 | Period 22018–2022 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | Patient-days | L/1000 PD | Hospitals | L | Patient-days | L/1000 PD | Hospitals | L | Patient-days | L/1000 PD | cIRR (95% CI) | ||

| Global | 69 | 1,060,407 | 32,686,816 | 32.4 | 66 | 327,729 | 14,343,161 | 22.8 | 69 | 732,678 | 18,343,655 | 39.9 | 1.75 (1.74–1.76) |

| Large | 9 | 550,083 | 13,271,247 | 41.4 | 9 | 171,741 | 6,131,594 | 28.0 | 9 | 378,342 | 7,139,653 | 53.0 | 1.89 (1.88–1.90) |

| Medium | 18 | 323,059 | 11,890,023 | 27.2 | 18 | 100,744 | 4,985,980 | 20.2 | 18 | 222,315 | 6,904,043 | 32.2 | 1.59 (1.58–1.61) |

| Small | 37 | 159,847 | 6,687,620 | 23.9 | 34 | 47,656 | 2,896,194 | 16.5 | 37 | 112,191 | 3,791,426 | 29.6 | 1.80 (1.78–1.82) |

| Specialty hospital | 5 | 27,418 | 837,926 | 32.7 | 5 | 7,588 | 329,393 | 23.0 | 5 | 19,83 | 508,533 | 39.0 | 1.69 (1.65–1.74) |

| ICU | 37 | 211,653 | 2,334,018 | 90.7 | 33 | 54,775 | 932,735 | 58.7 | 39 | 156,878 | 1,401,283 | 112.0 | 1.91 (1.89–1.92) |

| Large | 9 | 139,293 | 1,396,873 | 99.7 | 8 | 36,868 | 582,059 | 63.3 | 9 | 102,425 | 814,814 | 125.7 | 1.98 (1.96–2.01) |

| Medium | 17 | 64,755 | 816,385 | 79.3 | 17 | 16,43 | 304,322 | 54.0 | 17 | 48,325 | 512,063 | 94.4 | 1.75 (1.72–1.78) |

| Small | 11 | 7,605 | 120,76 | 63.0 | 8 | 1,477 | 46,354 | 31.9 | 11 | 6,128 | 74,406 | 82.4 | 2.58 (2.44–2.74) |

| Non-ICU | 69 | 848,754 | 30,352,798 | 28.0 | 66 | 272,954 | 13,410,426 | 20.4 | 69 | 575,8 | 16,942,372 | 34.0 | 1.67 (1.66–1.68) |

| Large | 9 | 410,79 | 11,874,374 | 34.6 | 9 | 134,873 | 5,549,535 | 24.3 | 9 | 275,917 | 6,324,839 | 43.6 | 1.79 (1.78–1.81) |

| Medium | 18 | 258,304 | 11,073,638 | 23.3 | 18 | 84,314 | 4,681,658 | 18.0 | 18 | 173,99 | 6,391,980 | 27.2 | 1.51 (1.50–1.52) |

| Small | 37 | 152,242 | 6,566,860 | 23.2 | 34 | 46,179 | 2,849,840 | 16.2 | 37 | 106,063 | 3,717,020 | 28.5 | 1.76 (1.74–1.78) |

| Specialty hospital | 5 | 27,418 | 837,926 | 32.7 | 5 | 7,588 | 329,393 | 23.0 | 5 | 19,83 | 508,533 | 39.0 | 1.69 (1.65–1.74) |

L: liters; PD: patient-days; cIRR: crude incidence rate ratio; CI: confidence interval.

The annual consumption of ABHR from 2014 to 2022, categorized by hospital groups, is shown in Fig. 1. Across all hospital sizes, ABHR consumption significantly increased in 2020, coinciding with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. By 2022, global consumption levels returned to figures similar to those observed in 2019. In large hospitals, consumption levels remained higher than in the early study years (2014–2017) but did not exceed levels observed in 2018–2019. For small and specialized hospitals, consumption levels post-2020 either approached or fell below pre-pandemic levels. Fig. 2 illustrates the trends in ABHR consumption between ICUs and non-ICU wards from 2014 to 2022. Overall, ABHR consumption has risen significantly in 2020 in both ICUs and non-ICU wards, with ICUs showing higher levels of use, almost 175L/1000 patient-days. The distribution of ABHR consumption across 69 hospitals, categorized by size: large, medium, small, and specialty hospitals is shown in supplementary Fig. S4. Significant variability in ABHR consumption both within and between hospital size categories.

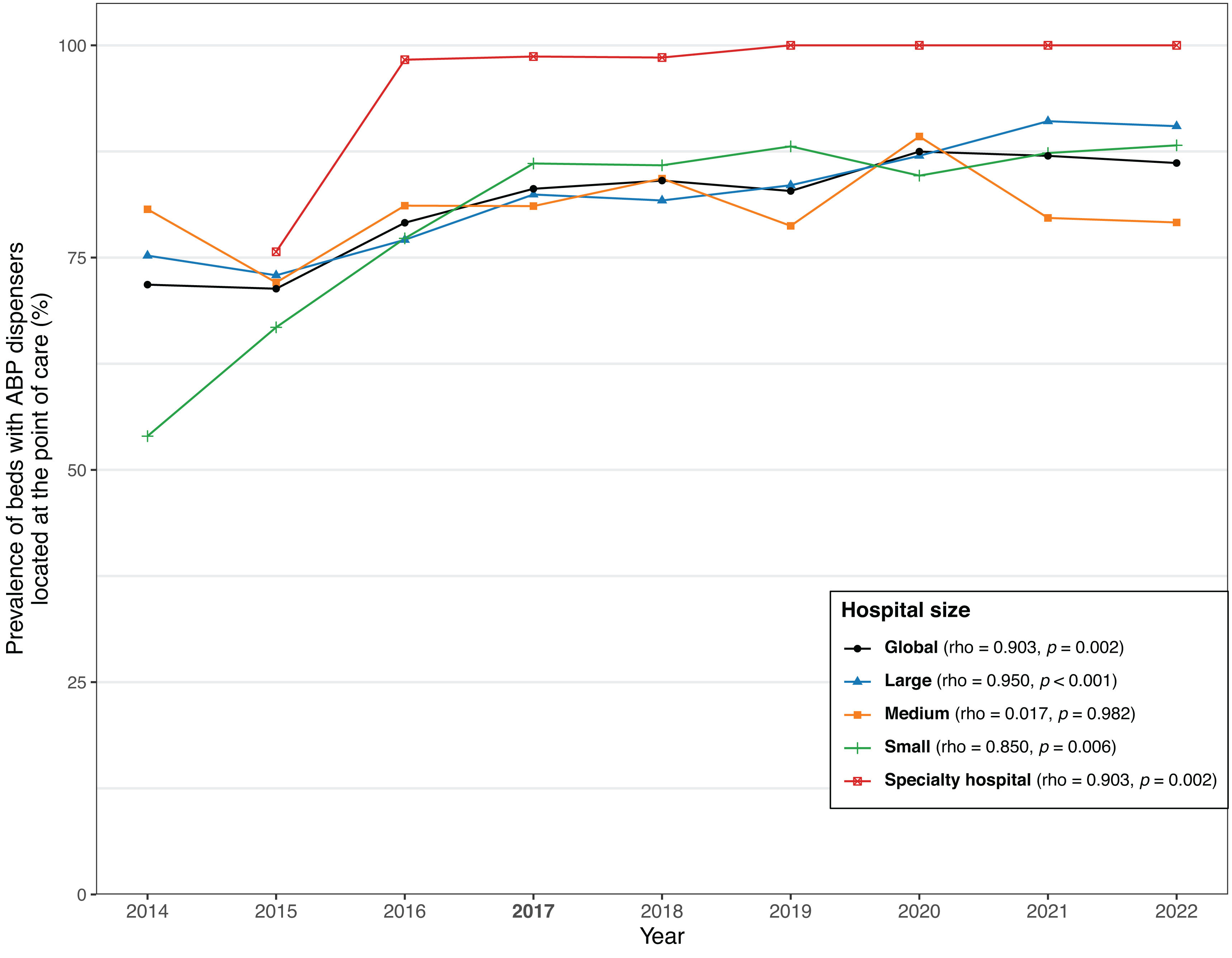

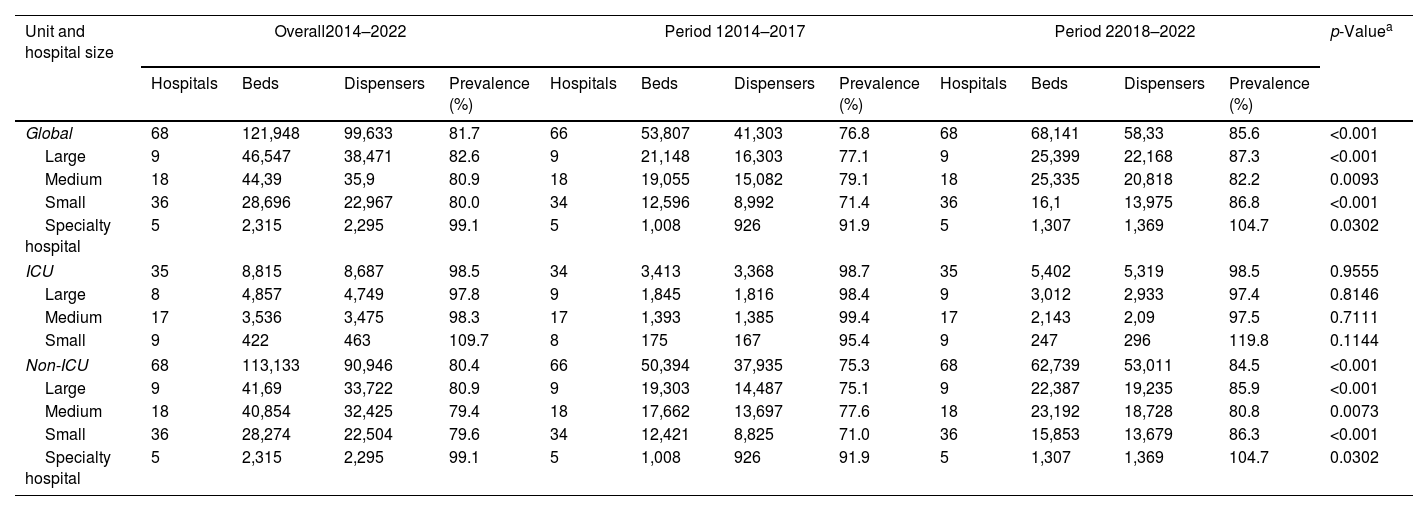

The prevalence of hospital beds with ABHR dispensers at the POC, segmented by hospital groups and periods is shown in Table 2. The global prevalence of beds with ABHR dispensers at POC increased from 76.8% in Period 1 to 85.6% in Period 2, indicating a significant rise in availability over time (p<0.001). Focusing on the type of ward, the overall prevalence of dispensers at POC remained stable in ICUs with negligible change between the two periods. Non-ICU units showed a significant increase from 75.3% in Period 1 to 84.5% in Period 2 (p<0.001). The increased availability of dispensers at the POC across all hospital sizes was particularly pronounced in small hospitals (Fig. 3).

Trends in the prevalence of beds equipped with alcohol-based preparation dispensers at the point of care.

| Unit and hospital size | Overall2014–2022 | Period 12014–2017 | Period 22018–2022 | p-Valuea | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitals | Beds | Dispensers | Prevalence (%) | Hospitals | Beds | Dispensers | Prevalence (%) | Hospitals | Beds | Dispensers | Prevalence (%) | ||

| Global | 68 | 121,948 | 99,633 | 81.7 | 66 | 53,807 | 41,303 | 76.8 | 68 | 68,141 | 58,33 | 85.6 | <0.001 |

| Large | 9 | 46,547 | 38,471 | 82.6 | 9 | 21,148 | 16,303 | 77.1 | 9 | 25,399 | 22,168 | 87.3 | <0.001 |

| Medium | 18 | 44,39 | 35,9 | 80.9 | 18 | 19,055 | 15,082 | 79.1 | 18 | 25,335 | 20,818 | 82.2 | 0.0093 |

| Small | 36 | 28,696 | 22,967 | 80.0 | 34 | 12,596 | 8,992 | 71.4 | 36 | 16,1 | 13,975 | 86.8 | <0.001 |

| Specialty hospital | 5 | 2,315 | 2,295 | 99.1 | 5 | 1,008 | 926 | 91.9 | 5 | 1,307 | 1,369 | 104.7 | 0.0302 |

| ICU | 35 | 8,815 | 8,687 | 98.5 | 34 | 3,413 | 3,368 | 98.7 | 35 | 5,402 | 5,319 | 98.5 | 0.9555 |

| Large | 8 | 4,857 | 4,749 | 97.8 | 9 | 1,845 | 1,816 | 98.4 | 9 | 3,012 | 2,933 | 97.4 | 0.8146 |

| Medium | 17 | 3,536 | 3,475 | 98.3 | 17 | 1,393 | 1,385 | 99.4 | 17 | 2,143 | 2,09 | 97.5 | 0.7111 |

| Small | 9 | 422 | 463 | 109.7 | 8 | 175 | 167 | 95.4 | 9 | 247 | 296 | 119.8 | 0.1144 |

| Non-ICU | 68 | 113,133 | 90,946 | 80.4 | 66 | 50,394 | 37,935 | 75.3 | 68 | 62,739 | 53,011 | 84.5 | <0.001 |

| Large | 9 | 41,69 | 33,722 | 80.9 | 9 | 19,303 | 14,487 | 75.1 | 9 | 22,387 | 19,235 | 85.9 | <0.001 |

| Medium | 18 | 40,854 | 32,425 | 79.4 | 18 | 17,662 | 13,697 | 77.6 | 18 | 23,192 | 18,728 | 80.8 | 0.0073 |

| Small | 36 | 28,274 | 22,504 | 79.6 | 34 | 12,421 | 8,825 | 71.0 | 36 | 15,853 | 13,679 | 86.3 | <0.001 |

| Specialty hospital | 5 | 2,315 | 2,295 | 99.1 | 5 | 1,008 | 926 | 91.9 | 5 | 1,307 | 1,369 | 104.7 | 0.0302 |

The study highlights significant trends in ABHR consumption across participating VINCat hospitals, with an overall increase in ABHR use between 2014 and 2022 in all hospital groups. The increase in ABHR use aligns with global initiatives and recommendations from organizations such as the WHO that emphasize the importance of hand hygiene in reducing HAIs.13

The consumption of ABHR varied across different countries in Europe. In a broader European study (PROHIBIT), the median ICU ABHR consumption was 66mL per patient-day, with considerable variation by country. Our findings, with a consumption rate of 90.7L/1000 patient-days in ICUs, place Catalonia among the higher consumers of ABHR in Europe, comparable to Germany but significantly higher than the European mean.14,15

The data analysis suggests that hospital size plays a significant role in ABHR consumption. Larger hospitals demonstrated higher ABHR consumption per patient-day compared to smaller hospitals. This could be attributed to these facilities’ more complex patient care needs and higher patient volumes.

One key observation from the study is the dramatic rise in ABHR consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The surge in ABHR consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic mirrors global trends, reflecting heightened hand hygiene practices during the crisis. However, by 2022, global consumption levels returned to figures similar to those observed in 2019, suggesting a normalization of hand hygiene practices as the pandemic's immediate impact subsided. This trend was particularly pronounced in small and specialized hospitals, where consumption levels either approached or fell below pre-pandemic figures, potentially due to resource limitations or decreased prioritization of hand hygiene. In contrast, large hospitals demonstrated sustained increases compared to the early study years (2014–2017), although consumption did not exceed 2018–2019 levels. These findings underscore the importance of maintaining robust hand hygiene programs, particularly in smaller facilities, to sustain compliance during non-crisis periods. For instance, a study on COVID-19 and ABHR effectiveness highlighted the critical role of hand hygiene in controlling virus transmission, with WHO-recommended formulations showing strong virucidal activity against SARS-CoV-2.16 This reinforces the heightened ABHR use during the pandemic, as seen in our data and other European countries like Italy, where ABHR consumption peaked in 2020 but decreased significantly by 2022.17

Our study showed a notable improvement in the availability of ABHR dispensers at POC. This increase in availability is crucial as it facilitates compliance with hand hygiene practices by making ABHR more accessible to healthcare workers. The results indicate that more hospitals, especially smaller ones, have made efforts to increase the number of ABHR dispensers, which is an essential component of WHO's multimodal strategy for hand hygiene improvement.7,18

Our study has several strengths, it provides ABHR consumption across a large number of hospitals in Catalonia, representing various hospital sizes and specializations over an extended period. This allows for a robust understanding of long-term trends in hand hygiene practices. Our study has captured the impact of COVID-19 and the significant increase in ABHR consumption. In addition to tracking ABHR consumption, the study evaluates the availability of ABHR dispensers at the POC. This is a key strength as it connects consumption data with accessibility, a vital component of hand hygiene compliance.

Regarding limitations, our study does not include direct observation of healthcare workers’ hand hygiene practices. This could provide a more complete picture of actual compliance. Furthermore, the study relies on data provided by hospital infection control personnel. There is a possibility of inconsistencies in reporting ABHR consumption and dispenser availability, especially given the variability in hospital sizes and resources. Finally, although the study is comprehensive for the region of Catalonia, its findings may not be fully applicable to other regions or countries with different healthcare systems, infection control policies, or levels of resources.

In conclusion, the study demonstrates that the VINCat program has successfully monitored and facilitated improvements in ABHR consumption and availability, contributing to enhanced hand hygiene compliance in Catalonia. The significant increases during the COVID-19 pandemic highlight the impact of global health crises on infection prevention practices.

Future efforts should focus on sustaining progress in high-risk settings such as ICUs while addressing gaps in compliance and accessibility in non-ICU wards, where challenges may still persist.

FundingThe VINCat program is supported by public funding from the Catalan Health Service, Department of Health, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support.

Maria José Moreno Martinez and Clara Sala Jofre, Hospital Dos de Maig, Consorci Sanitari Integral; Maria Carmen Alvarez Moya and Vicens Diaz-Brito Fernandez, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Deu; MªTeresa Ros Prat, Fundació Sant Hospital. La Seu d’Urgell; Elisa Montiu González and María Ramirez Hidalgo, Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida; Esther Rodriguez Gías and Montserrat Olona Cabases, Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona; Mireia Duch Pedret and Anibal Calderon Collantes, Badalona Serveis Assistencials; Silvia Alvarez and Marta Andrés Santamaria, Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa; David Blancas Altabella, Consorci Sanitari Alt Penedès i Garraf - Hospital Sant Camil; Mariló Marimón Morón and Roger Malo Barres, Hospital Universitari General de Catalunya; Alejandro Smithson Amat, Fundació Hospital de l’Esperit Sant; Mª de Gracia García Ramírez and José Vargas-Machuca Fernández, Centre MQ Reus Francisco; Mª Carmen Eito Navasal and Ana Jiménez Zárate, Institut Català d’Oncologia L’Hospitalet; Laura Cabrera Jaime,Institut Català d’Oncologia Badalona; Jessica Rodríguez Garcia, Institut Català d’Oncologia Girona; Sara Burgués Estada and Eduardo Sáez Huerta, Clínica NovAliança de Lleida; Anna Martinez Sibat, Hospital de Campdevànol; Dolors Domenech Bague and Ricardo Gabriel Zules Oña, Hospital Universitari Dr. Josep Truet; Anna Escobar Juan and Manel Panisello Bertomeu, Hospital comarcal d’Amposta; Laura Grau Palafox and Marta Andrés Santamaria, Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa; Emilien Amar Devilleneuve and Mariona Secanell Espluga, Institut Guttmann; Rosa Laplace Enguídanos, Meritxell Guillemat Marrugat and Alexander Cordoba Castro, Hospital Del Vendrell; Alba Guitard QuerHospital Universitari Santa Maria; Anna Besolí Codina, Patricia Aguilera DiazConsorci hospitalari de Vic; Ana Felisa López Azcona and Simona Iftimie Iftimie, Hospital Universitari Sant Joan de Reus; Sandra Aznar Juncà and Carmen Felip Rovira, Clínica Salus Infirmorum; Mª Angels Pages Roura and Maria de la Roca Toda Savall, Hospital de Palamós; Pilar Girbal Portela and Josep Cucurull Canosa, Hospital de Figueres; Carme Ferrer Barberà and Dolors Rodriguez-Pardo, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron; Pilar de la Cruz Sole, Hospital Universitari Dexeus; Alexandra Lucia Moise and Marta Milián sanz, Hospital Pius de Valls; Mercè Claròs Ferret and Irene Sánchez Rodriguez, Hospital Sant Rafael; Irene Boix Gravalosa and Maria Alba Serra Juhé, Hospital d’Olot Comarcal de la Garrotxa; Montserrat Vaqué Franco and Yolanda Meije Castillo, Hospital de Barcelona.SCIAS; Montserrat Rovira Espès and José Carlos de la Fuente Redondo, Hospital Comarcal de Móra d’Ebre; Marie France Domenech Spaneda and Josep Rebull Fatsini, Hospital de Tortosa Verge de la Cinta; Lucrecia López González and Ana Coloma Conde, Consorci Hopitalari Universitari Moises Broggi; Montserrat Brugues Bruges and Judit Santamaria Rodriguez, Consorco Sanitari de l’anoia. Hospital d’Igualada; Nereida Barneda Darias and Eva Palau Gil, Clínica Girona; Demelza Maldonado López, Pilar Marzuelo Fuste and Elisabet Lerma Chippirraz, Hospital General de Granoller; David Pineda Fernández and Rosa Coll Colell, Hospital Universitari Sagrat Cor; Josep Farguell Carreras and Mireia Saballs Nadal, Hospital QuironSalud Barcelona; Ludivina Ibáñez Soriano, Espitau Val d’Aran; Angeles Garcia Flores and Roser Ferrer i Aguilera, Hospital Sant Jaume de Calella and Hospital Comarcal de Blanes; Cristina González Juanes and Juan Pablo Horcajada Gallego, Hoapital del Mar; Núria Bosch Ros, Hospital Sta. Caterina Girona; Anju Ram Devi and Teresa Domenech Forcadell,Clínica Terres de l’Ebre; María Cuscó Esteve and Laura Linares Gonzalez, Consorci Sanitari Alt Penedès i Garraf - Hospital Alt Penedés; Simón Juárez Zapata and Carles Alonso-Tarrés, Fundació Puigvert; Susana Galán Aguallo and Natalia Juan Serra, Centro Médico Teknon; Engracia Fernández Piqueras, Virginia Pomar Solchaga and Joaquin López-Contreras Gonzalez, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau; Olga Melé Sorolla and Cristina Ribó Bonet, Hospital Vithas Lleida; Lidia Martín Gonzalez and Ana Lérida Urteaga, Hospital de Viladecans; Dolors Mas Rubio, Mercè Solà Ferrer and Rafel Perez Vidal, Althaia, Xarxa Assistencial Universitària de Manresa. Hospital Sant Joan de Déu de Manresa; Conchita Hernández Magide, Susanna Camps Carmona and Oriol Gasch Blasi, Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí de Sabadell; Irma Casas Garcia, Laia Castella Fàbregas and Nieves Sopena Galindo, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol; Elena Vidal Diez and M. Pilar Barrufet Barque, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme. Hospital de Mataró.