Lung cancer (LC) screening detects tumors early. The prospective GESIDA 8815 study was designed to assess the usefulness of this strategy in HIV + people (PLHIV) by performing a low-radiation computed tomography (CT) scan.

Patients and methods371 heavy smokers patients were included (>20 packs/year), >45 years old and with a CD4+ <200 mm3 nadir. One visit and CT scan were performed at baseline and 4 for follow-up time annually.

Results329 patients underwent the baseline visit and CT (CT0) and 206 completed the study (CT1 = 285; CT2 = 259; CT3 = 232; CT4 = 206). All were receiving ART. A total >8 mm lung nodules were detected, and 9 early-stage PCs were diagnosed (4 on CT1, 2 on CT2, 1 on CT3 and 2 on CT4). There were no differences between those who developed LC and those who did not in sex, age, CD4+ nadir, previous lung disease, family history, or amount of packets/year. At each visit, other pathologies were diagnosed, mainly COPD, calcified coronary artery and residual tuberculosis lesions. At the end of the study, 38 patients quit smoking and 75 reduced their consumption. Two patients died from LC and 16 from other causes (p = 0.025).

ConclusionsThe design of the present study did not allow us to define the real usefulness of the strategy. Adherence to the test progressively decreased over time. The diagnosis of other thoracic pathologies is very frequent. Including smokers in an early diagnosis protocol for LC could help to quit smoking.

El cribado de cáncer de pulmón (CP) detecta tumores precozmente. El estudio prospectivo GESIDA 8815 se diseñó para valorar la utilidad de esta estrategia en personas VIH+ (PVVIH) mediante la realización de una tomografía computarizada (TC) de baja radiación.

Pacientes y métodosSe incluyeron 371 pacientes grandes fumadores (>20 paquetes-año), >45 años y con nadir de CD4+<200mm3. Se realizó una visita y TC basal y 4 de seguimiento anualmente.

ResultadosRealizaron la visita y TC basal (TC0) 329 pacientes y completaron el estudio 206 (TC1 = 285; TC2 = 259; TC3 = 232; TC4 = 206). Todos recibían TAR. Se detectaron 35 nódulos pulmonares > 8 mm y se diagnosticaron 9 CP en estadio precoz (4 en TC1, 2 en TC2, 1 en TC3 y 2 en TC4). No existieron diferencias entre los que desarrollaron CP y los que no en sexo, edad, nadir CD4+, patología pulmonar previa, antecedentes familiares ni número de paquetes/año. En cada visita se diagnosticaron otras patologías fundamentalmente EPOC, coronarias calcificadas y lesiones residuales de tuberculosis. Al finalizar el estudio 38 pacientes dejaron de fumar y 75 redujeron el consumo. Fallecieron 2 pacientes por CP y 16 por otras causas (p = 0,025).

ConclusionesEl diseño del presente estudio no permitió definir la utilidad real de la estrategia. La adherencia a la prueba disminuyó progresivamente a lo largo del tiempo. Es muy frecuente el diagnóstico de otras patologías torácicas. Incluir a pacientes fumadores en un protocolo de diagnóstico precoz de CP podría ayudar a dejar de fumar.

In recent years, non-AIDS-defining events (nADEs), including non-AIDS-defining cancers (nADCs), have become of particular interest to people living with HIV (PLHIV).1–5 In Spain, according to data presented in 2023 at the fourteenth National GeSIDA [AIDS working group] Congress,6 an incidence rate of 3.82 περ 1,000 person-years was found in men (95% CI: 3.46–4.22) and 4.21 περ 1,000 person-years in women (95% CI: 3.4–5.21), with lung cancer (LC) being the most frequent, with an incidence rate of 0.69 περ 1,000 (95% CI: 0.56–0.86). Smoking, which is very common in PLHIV, is one of the main drivers of its onset; the risk of getting cancer increases with age, and some epidemiological studies have found a higher incidence at younger ages in PLHIV.7 In addition, Sigel et al.8 found a higher incidence in PLHIV (2.04 περ 1,000 person-years) than in the HIV- population (1.19 περ 1,000 person-years), regardless of smoking status.

Although LC is a leading cause of death, until recently there has been no screening method for early diagnosis. The use of low-dose computed tomography (CT) is now being proposed, with its application resulting in a fall in mortality.9,10 The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)11 and the clinical guidelines of the European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS)12 recommend low-dose CT for patients aged 50–80 years with a cumulative tobacco consumption ≥20 packs/year or who have been smokers for up to 15 years.

Hulbert et al.13 published the first study in PLHIV in 2014 with inconclusive results, which encouraged us to conduct this study, the aim of which was to try to define the utility of using low-dose CT as an early detection system for LC in this population.

MethodsObjectives- 1

The main objective was to evaluate the utility of serial low-dose chest CT for early detection of LC in a group of PLHIV at high risk of developing cancer.

- 2

The secondary objectives were to describe the radiological findings, other than LC, found in each CT scan and the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches derived from them.

A prospective study was designed with four-year patient follow-up, which was conducted at the Internal Medicine-HIV Unit, Pulmonology and Radiodiagnostics Departments of six Spanish hospitals. The population was selected from those PLHIV seen at the clinic who met the inclusion criteria.

Information on each patient was analysed at the baseline visit, where clinical-epidemiological data, characteristics and stage of HIV infection, risk behaviours and family history that could condition the development of LC were collected.

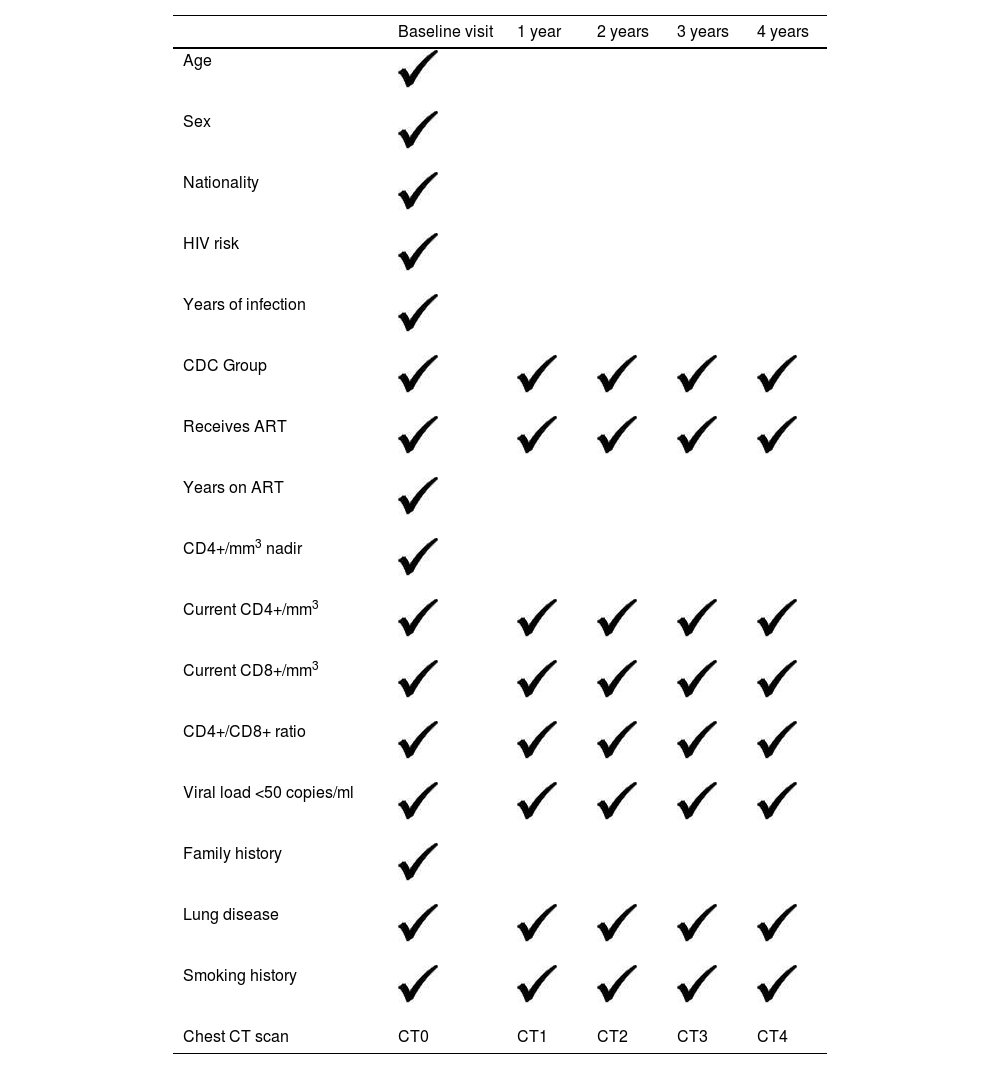

The timeline for the study is shown in Table 1.

A CT scan was performed at baseline and every year thereafter for four years (five CT scans).

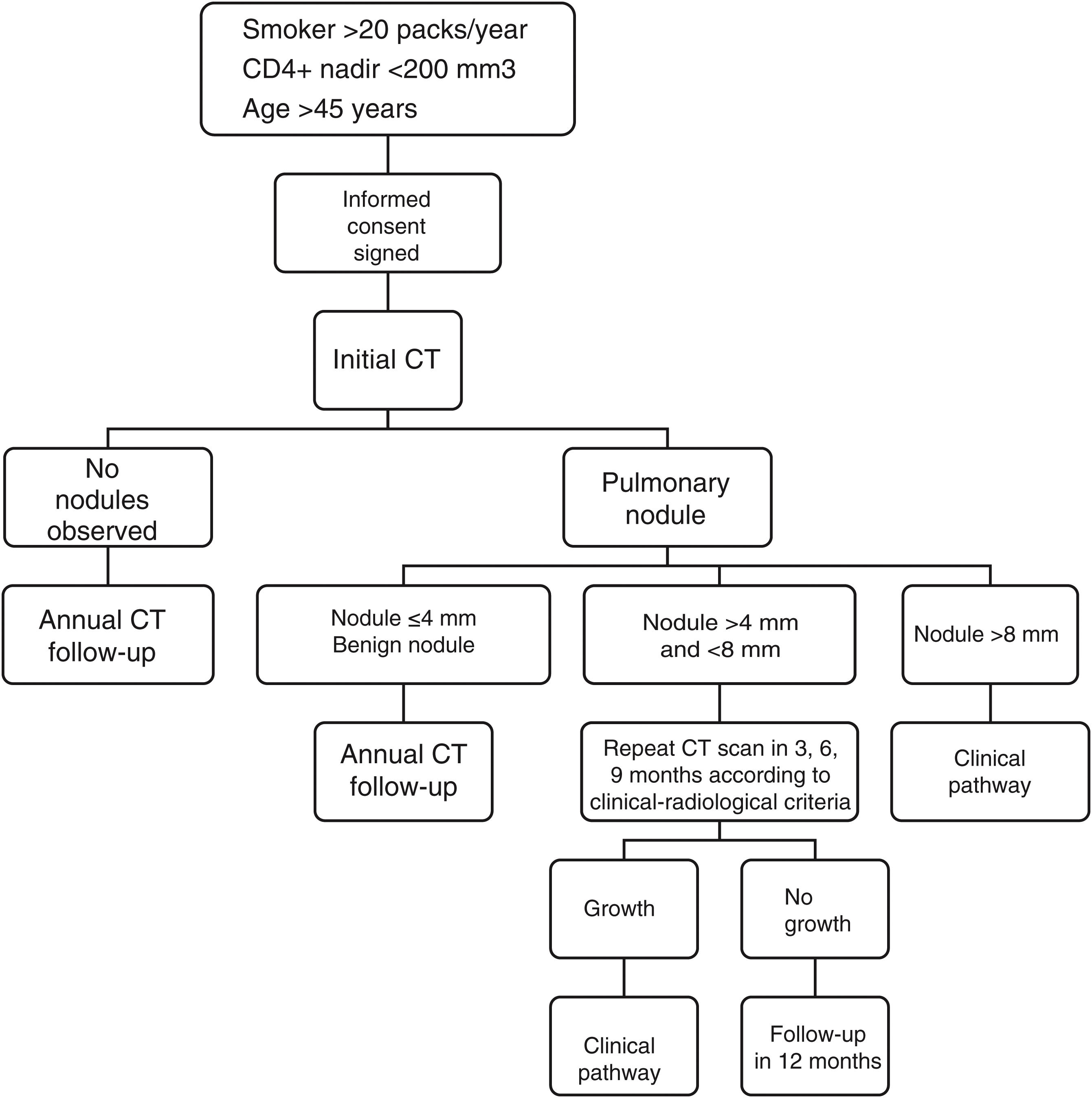

The radiological studies were performed after the patient came to the clinic and signed the informed consent form, and the same diagnostic algorithm was applied to all (Fig. 1). The analysis was performed by the radiologist at the usual workstation with a low-dose chest CT protocol without intravenous contrast, and low-dose inhalation (120 kV, 100 mA) with 3-mm axial reconstruction, pitch 1 and 0.6-mm collimation. A standard lung (window width, 1,500 HU; window level, −600 HU) and mediastinum (window width, 400 HU; window level, 40 HU) reconstruction algorithm and axial plane maximum intensity projection post-processing were used. The results were recorded on a standardised form and classified as follows:

- •

Negative results: no pulmonary nodules. The CT scan was repeated at 12 months.

- •

Positive results: pulmonary nodules were identified. Any parenchymal nodule was considered positive, excluding densely calcified nodules.

Size was assessed by measuring the largest diameter in the transverse plane. They were classified into three categories: ≤4 mm, 5–8 mm and >8 mm. The approach to size was:

- 1

Nodules ≤4 mm were considered low suspicion and follow-up was performed at 12 months.

- 2

A follow-up algorithm was applied to the indeterminate nodules (5–8 mm) according to medical criteria and an interim CT scan was performed between three and nine months.

- 3

Nodules >8 mm were referred to a clinical pathway, with PET-CT and/or dynamic CT study, according to radiological criteria. In the event of a positive result, additional tests were performed as deemed necessary by the physician responsible for the patient.

A descriptive study was also conducted on the rest of the findings.

Low-dose CT was the only procedure performed outside of each patient’s routine visit. When lung disease requiring additional diagnostic and therapeutic measures was detected, the patient was informed and the appropriate measures were taken.

Inclusion criteriaThe patient had to meet all of the following:

- 1

Confirmed HIV infection with CD4+ lymphocyte nadir <200/mm3.

- 2

Being a heavy smoker consuming ≥20 pack-years at the time of inclusion or having smoked for up to the previous 15 years.

- 3

Being >45 years old.

- 4

Signing the informed consent form

If the patient met any of the following:

- 1

A chest CT scan within the previous 18 months.

- 2

Pregnancy.

- 3

Previous history of LC.

- 4

Acute respiratory infection which, once resolved, allowed the patient to be re-assessed as a candidate for inclusion into the study.

All data were collected in the REDCap electronic CRD (Copyright 2006-2013 Vanderbilt University). A descriptive analysis of socio-demographic and HIV-related data, smoking, LC and CT results at baseline and follow-up visits was performed using frequency tables for categorical variables and mean (standard deviation) or median and interquartile range for quantitative variables with normal or non-normal distribution, respectively. Differences in the characteristics of individuals at the baseline visit according to LC diagnosis at follow-up were assessed using the chi-square test of independence for categorical variables and Student's t-test or the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test for quantitative variables with normal or non-normal distribution, respectively.

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 17.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical aspectsThe study was conducted in accordance with the protocol, the principles set out in the current revised version of the Declaration of Helsinki (Seoul, October 2008) and in accordance with applicable regulatory requirements, in particular the ICH Tripartite Harmonised Guideline for Good Clinical Practice 1996 and the Spanish Clinical Trials Royal Decree 223/2004, which fully transposes the provisions of European Directive 2001/20/EC.14 All patients signed the informed consent form and the protocol was approved by the Hospital Universitario La Paz Ethics Committee.

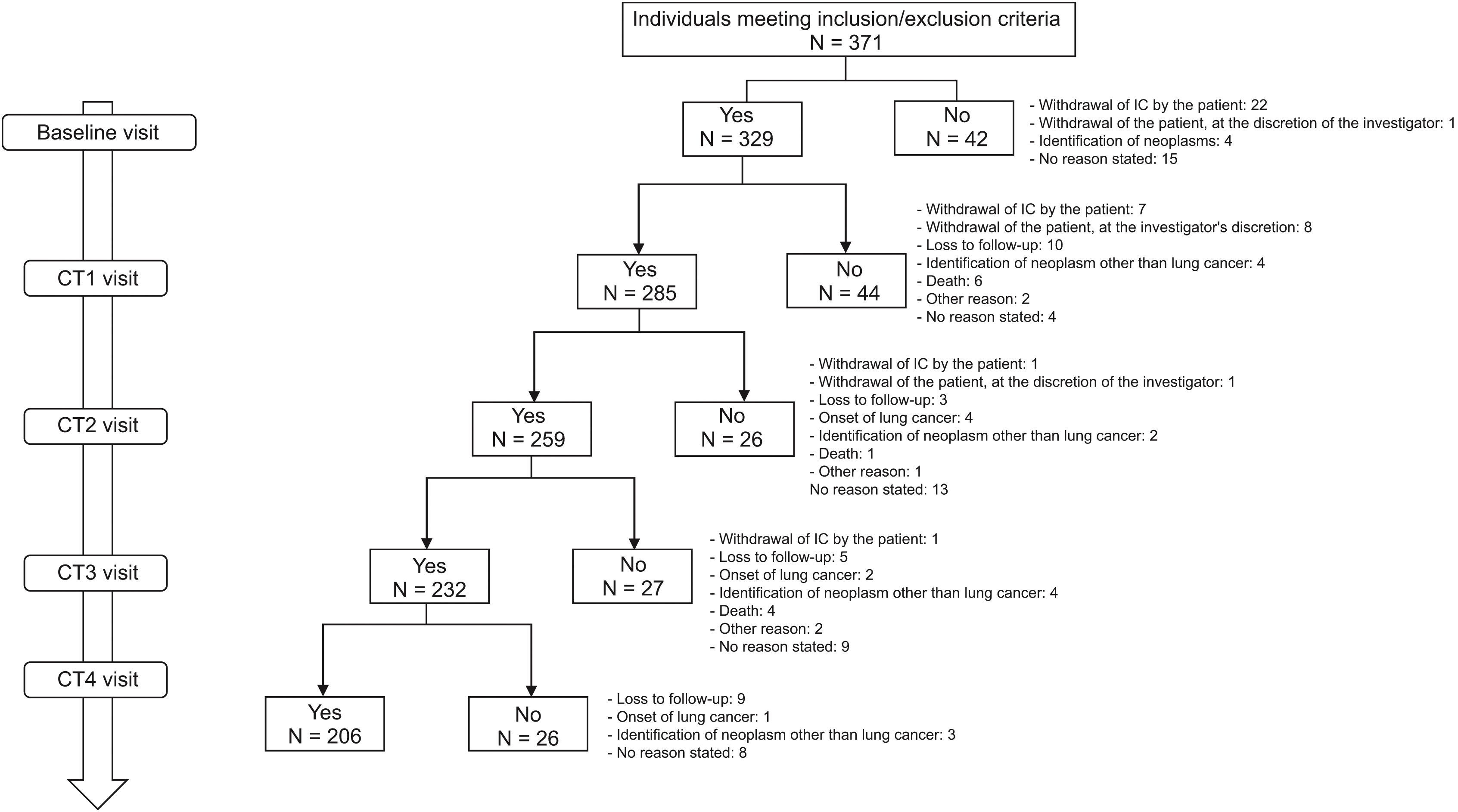

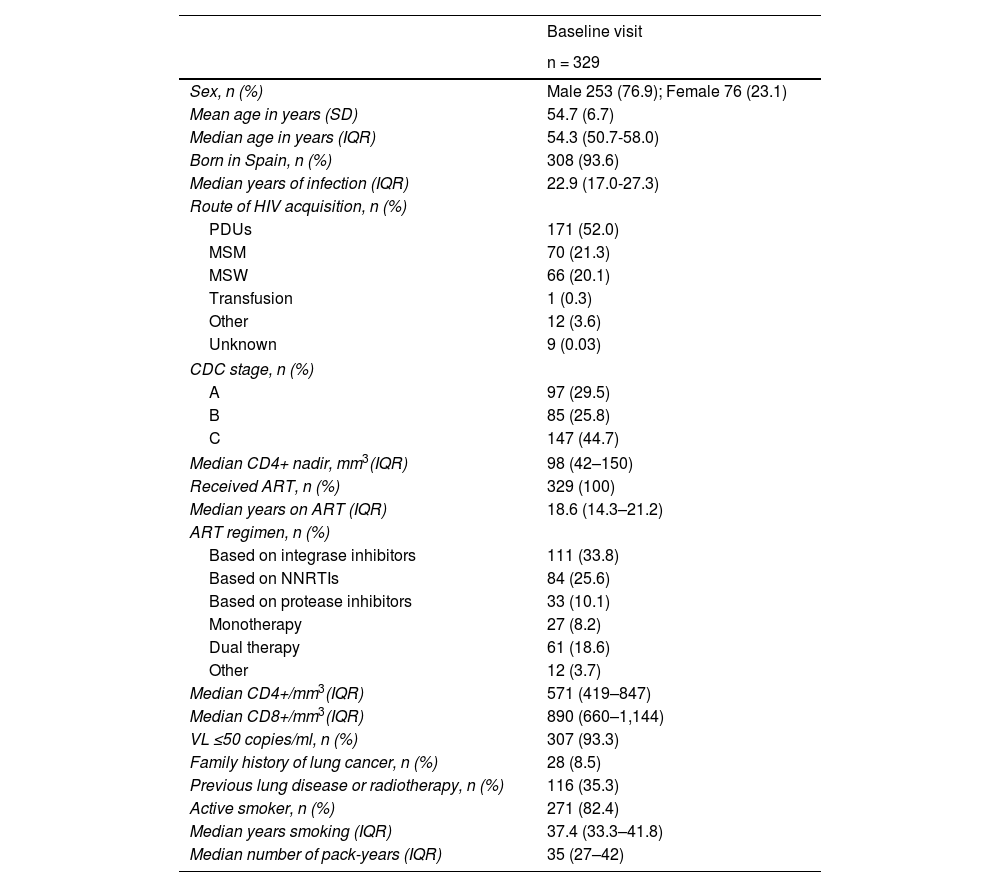

ResultsA total of 371 patients were included in the study, 329 of whom had a baseline visit and CT scan (CT0) and 206 completed follow-up (CT1 = 285; CT2 = 259; CT3 = 232; CT4 = 206). The flow chart of the study population is shown in Fig. 2. Overall, 76.9% were Spanish-born males (93.6%), with a mean age (SD) of 54.7 (6.7) years. The main routes of HIV acquisition were parenteral drug use (52%) and sexual intercourse (21.3% homosexual; 20.1% heterosexual). The median CD4+ lymphocyte nadir cells/mm3 was 98 (IQR = 42–150) and 147 patients (44.7%) met AIDS criteria. All were on antiretroviral therapy (ART) with a median number of treatment years of 18.6 (IQR = 14.3–21.2). In total, 111 patients (33.8%) were on an integrase inhibitor triple therapy ART regimen, 84 (25.6%) were on a non-nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) triple therapy regimen and 33 (10.1%) on a protease inhibitor triple therapy regimen. At baseline, the viral load was undetectable in 307 patients (93.3%), the median CD4+ lymphocytes/mm3 was 571 (IQR = 660–847) and the median CD8+ was 890 (IQR = 660–1,144). Only 28 (8.5%) had a family history of LC and 116 (35.3%) had a history of lung disease. The median time from smoking initiation to study entry was 37.4 years (IQR = 33.3–41.8), the median pack-years was 35 (IQR = 27–42), and 271 (82.4%) continued to smoke. Table 2 shows all the characteristics of the study population.

Socio-demographic data associated with HIV, smoking and lung cancer at the baseline visit.

| Baseline visit | |

|---|---|

| n = 329 | |

| Sex, n (%) | Male 253 (76.9); Female 76 (23.1) |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 54.7 (6.7) |

| Median age in years (IQR) | 54.3 (50.7-58.0) |

| Born in Spain, n (%) | 308 (93.6) |

| Median years of infection (IQR) | 22.9 (17.0-27.3) |

| Route of HIV acquisition, n (%) | |

| PDUs | 171 (52.0) |

| MSM | 70 (21.3) |

| MSW | 66 (20.1) |

| Transfusion | 1 (0.3) |

| Other | 12 (3.6) |

| Unknown | 9 (0.03) |

| CDC stage, n (%) | |

| A | 97 (29.5) |

| B | 85 (25.8) |

| C | 147 (44.7) |

| Median CD4+ nadir, mm3(IQR) | 98 (42–150) |

| Received ART, n (%) | 329 (100) |

| Median years on ART (IQR) | 18.6 (14.3–21.2) |

| ART regimen, n (%) | |

| Based on integrase inhibitors | 111 (33.8) |

| Based on NNRTIs | 84 (25.6) |

| Based on protease inhibitors | 33 (10.1) |

| Monotherapy | 27 (8.2) |

| Dual therapy | 61 (18.6) |

| Other | 12 (3.7) |

| Median CD4+/mm3(IQR) | 571 (419–847) |

| Median CD8+/mm3(IQR) | 890 (660–1,144) |

| VL ≤50 copies/ml, n (%) | 307 (93.3) |

| Family history of lung cancer, n (%) | 28 (8.5) |

| Previous lung disease or radiotherapy, n (%) | 116 (35.3) |

| Active smoker, n (%) | 271 (82.4) |

| Median years smoking (IQR) | 37.4 (33.3–41.8) |

| Median number of pack-years (IQR) | 35 (27–42) |

ART: antiretroviral therapy; IQR: interquartile range; MSM: men who have sex with men; MSW: men who have sex with women (heterosexual transmission); PDUs: parenteral drug users; SD: standard deviation; VL: viral load.

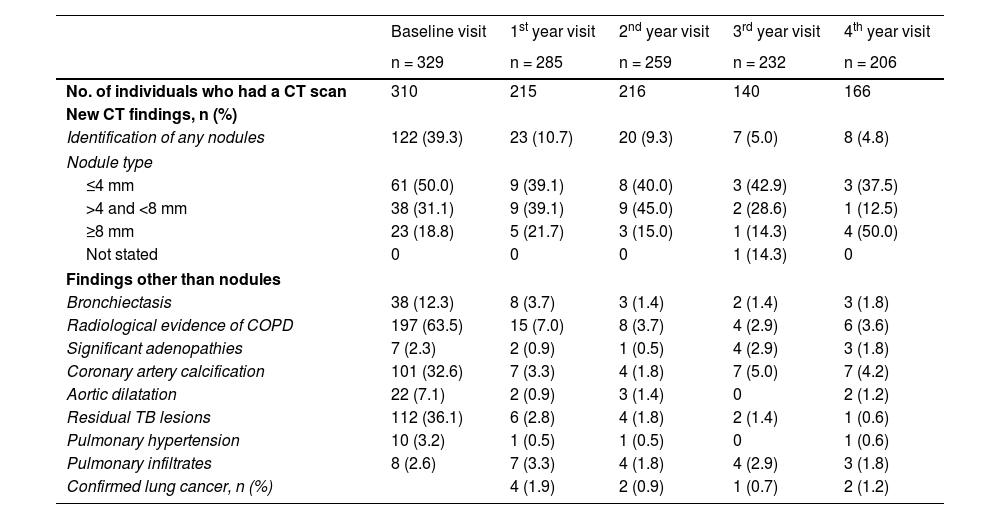

Chest conditions other than pulmonary nodules were diagnosed at each visit, the most common findings being radiological evidence of COPD (230 patients), coronary artery calcification (126 patients) and residual lesions of tuberculosis (125 patients). Table 3 describes the radiological findings at each visit. Patients in whom pulmonary disease was detected were referred to pulmonology, and those with aortic dilatation were referred to vascular surgery. Although low-dose CT is not specific for calcium quantification in coronary arteries, in the 126 (38.2%) where calcification was found, measures to control cardiovascular risk were intensified.

Information on the outcome of the CT scan at the baseline and follow-up visits.

| Baseline visit | 1st year visit | 2nd year visit | 3rd year visit | 4th year visit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 329 | n = 285 | n = 259 | n = 232 | n = 206 | |

| No. of individuals who had a CT scan | 310 | 215 | 216 | 140 | 166 |

| New CT findings, n (%) | |||||

| Identification of any nodules | 122 (39.3) | 23 (10.7) | 20 (9.3) | 7 (5.0) | 8 (4.8) |

| Nodule type | |||||

| ≤4 mm | 61 (50.0) | 9 (39.1) | 8 (40.0) | 3 (42.9) | 3 (37.5) |

| >4 and <8 mm | 38 (31.1) | 9 (39.1) | 9 (45.0) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (12.5) |

| ≥8 mm | 23 (18.8) | 5 (21.7) | 3 (15.0) | 1 (14.3) | 4 (50.0) |

| Not stated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

| Findings other than nodules | |||||

| Bronchiectasis | 38 (12.3) | 8 (3.7) | 3 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (1.8) |

| Radiological evidence of COPD | 197 (63.5) | 15 (7.0) | 8 (3.7) | 4 (2.9) | 6 (3.6) |

| Significant adenopathies | 7 (2.3) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.9) | 3 (1.8) |

| Coronary artery calcification | 101 (32.6) | 7 (3.3) | 4 (1.8) | 7 (5.0) | 7 (4.2) |

| Aortic dilatation | 22 (7.1) | 2 (0.9) | 3 (1.4) | 0 | 2 (1.2) |

| Residual TB lesions | 112 (36.1) | 6 (2.8) | 4 (1.8) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (0.6) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 10 (3.2) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Pulmonary infiltrates | 8 (2.6) | 7 (3.3) | 4 (1.8) | 4 (2.9) | 3 (1.8) |

| Confirmed lung cancer, n (%) | 4 (1.9) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.2) | |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT: computed tomography; TB: tuberculosis.

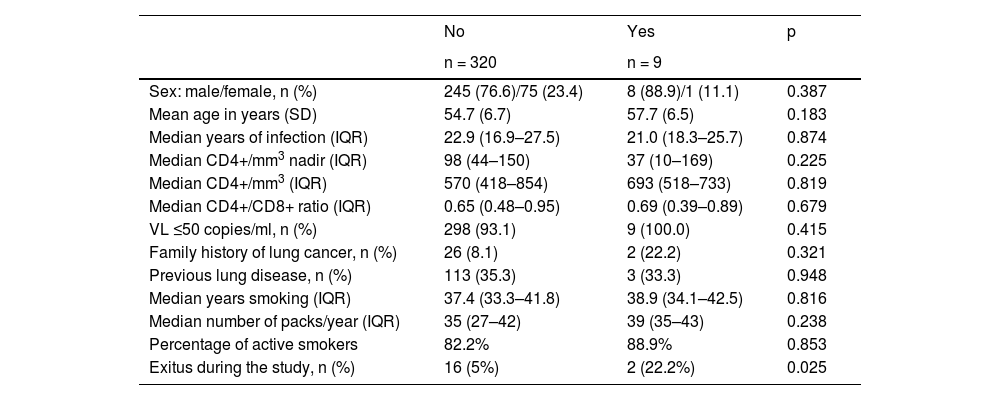

Some 180 lung nodules were detected, but only 35 were >8 mm (23 at CT0, 5 at CT1, 3 at CT2, 1 at CT3 and 4 at CT4). All were included in the clinical pathway of the corresponding Pulmonology Department, diagnosed by fibrobronchoscopy in seven patients and endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) in two, a total of nine LC (2.7% of the total number of patients included; 9.16 περ 1,000 person-years) in early stage (4 in CT1, 2 in CT2, 1 in CT3 and 2 in CT4). There were no significant differences between those who developed LC and those who did not in terms of sex, age, years of HIV infection, CD4+ lymphocyte nadir, CD4+ lymphocytes at baseline, CD4+/CD8+ ratio, previous lung disease, family history, time since initiation of smoking and number of pack-years (Table 4). Mortality was significantly higher in the group in which LC was diagnosed (p = 0.025), and at the end of the study 18 patients (5.5%) had died: two from LC and 16 from other causes (p = 0.025), the most common of which was a non-pulmonary neoplasm (six patients, 33.3%), followed by non-neoplastic liver disease (three patients, 16.7%)

Socio-demographic characteristics associated with HIV, smoking and lung cancer at the baseline visit by lung cancer diagnosis at follow-up.

| No | Yes | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 320 | n = 9 | ||

| Sex: male/female, n (%) | 245 (76.6)/75 (23.4) | 8 (88.9)/1 (11.1) | 0.387 |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 54.7 (6.7) | 57.7 (6.5) | 0.183 |

| Median years of infection (IQR) | 22.9 (16.9–27.5) | 21.0 (18.3–25.7) | 0.874 |

| Median CD4+/mm3 nadir (IQR) | 98 (44–150) | 37 (10–169) | 0.225 |

| Median CD4+/mm3 (IQR) | 570 (418–854) | 693 (518–733) | 0.819 |

| Median CD4+/CD8+ ratio (IQR) | 0.65 (0.48–0.95) | 0.69 (0.39–0.89) | 0.679 |

| VL ≤50 copies/ml, n (%) | 298 (93.1) | 9 (100.0) | 0.415 |

| Family history of lung cancer, n (%) | 26 (8.1) | 2 (22.2) | 0.321 |

| Previous lung disease, n (%) | 113 (35.3) | 3 (33.3) | 0.948 |

| Median years smoking (IQR) | 37.4 (33.3–41.8) | 38.9 (34.1–42.5) | 0.816 |

| Median number of packs/year (IQR) | 35 (27–42) | 39 (35–43) | 0.238 |

| Percentage of active smokers | 82.2% | 88.9% | 0.853 |

| Exitus during the study, n (%) | 16 (5%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0.025 |

IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; VL: viral load.

All patients were informed of the benefits of smoking cessation and contact with the smoking cessation units in each centre was facilitated. By the end of the study, 38 had quit smoking and 75 had significantly reduced their tobacco use.

DiscussionLC is the most deadly of all cancers, causing 1.80 million deaths worldwide in 2020, according to the WHO. In Spain, 30,000 cases are diagnosed annually and 23,000 people die from it. The number of new cases per year has been increasing and is likely to rise still further.15,16 Screening detects tumours early, when they are still incipient and therefore curable, and reduces mortality by 18–39%. Early detection is facilitated by regular low-dose CT scans.10–12 In the United States, it is indicated for people between 50 and 80 years of age who smoke >20 packs/year or who have smoked for the last 15 years.10,11 In Spain, LC screening is not universally included in the service portfolio of the national health system, and its utility in PLHIV has been far from established. Fortunately, in November 2023, the Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica [Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery] (SEPAR) announced the start of the Cancer Screening, Smoking Cessation and Respiratory Assessment (CASSANDRA) pilot project, which aims to demonstrate the viability, feasibility and cost-effectiveness of LC screening programmes in Spain.17 In addition, a multi-centre clinical trial on comprehensive screening for nADCs is currently ongoing in PLHIV and also includes the LC screening strategy.18

It has been postulated that LC is more common in PLHIV, regardless of smoking history, and that its onset is earlier, possibly due to immune disorders.4,8,19 Therefore, in addition to being heavy smokers (≥20 packs/year), the inclusion criteria stipulated the age of 45 years (although in Spain the mean age at diagnosis is 64 years) and that patients must have had a nadir <200 CD4 lymphocytes/mm3. Although the incidence was higher in the four-year follow-up than in other series8 (9.16 περ 1,000 person-years), in absolute numbers only nine cancers were diagnosed in the subsequent CT scans, with no differences found in terms of age or CD4 lymphocytes between patients who developed LC and those who did not. As such, tobacco use should probably be considered the key factor in implementing the screening programme, with factors derived from HIV infection, such as the CD4+ lymphocyte nadir, being less important.7,19,20 However, the median CD4+ nadir in participants with LC was unmistakably lower, but not significantly different (probably due to the small number of cases) to patients without LC (37 vs 98, respectively). Despite this inconclusive finding, we believe that setting the nadir of less than 200 CD4+ lymphocytes/mm3 as an inclusion criterion was a limiting factor in our study. Focusing only on the criteria established by the USPSTF11 or EACS12 for screening would have allowed us to better define the real utility of the strategy. Kong et al.21 conducted a study similar to ours with patients who had >500 CD4+ lymphocytes/mm3 and observed a similar reduction in mortality as in the general population, meaning it should be regarded as a useful strategy to implement in the follow-up of PLHIV.

Although Díaz-Álvarez et al.22 published a pilot study in 2021 demonstrating the advantages of performing low-dose CT for early diagnosis of LC, the aim of this study was to confirm the validity of the strategy with serial CT scans. While at the individual level the advantages of the nine early diagnoses were significant, in the absence of a comparator group it is difficult to assess their overall benefits. One of the fundamental drawbacks we encountered was the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,23 which meant that the opportunity to perform many examinations was lost, as 329 patients started the study but only 206 completed it. However, it is not only this circumstance that complicated follow-up, as substantial losses to follow-up are common to all long-term studies. In fact, Islam et al.24 found that only 12% of 73 PLHIV who had a low-dose CT scan returned for a second CT scan, demonstrating markedly lower adherence to the scan than that observed in the general population.

The fact that a lung CT scan in asymptomatic individuals also detects other conditions means that other diseases can be monitored more closely and allows therapeutic or preventive measures to be taken that would not otherwise be taken. Despite all these advantages, the possibility of false positives that may lead to unnecessary invasive diagnostic procedures should not be forgotten.25 In any cancer screening programme (whether for lung, breast, prostate or colon cancer), the benefit to be gained should be considered greater than the risk to healthy individuals.26,27 In our study, both at baseline and follow-up visits, multiple findings were found that led to diagnostic and therapeutic approaches that would not otherwise have been undertaken, which also provides an additional advantage in patient follow-up.

The main risk factor for LC is smoking, so smoking cessation should also be considered in all patients included in a LC early detection programme.28,29 In our study, a decrease in cigarette consumption was observed in 27% of the subjects and total cessation in 14%. Although this may be a circumstantial event, confronting patients with a possible diagnosis of LC could be seen as an incentive to quit smoking. The combined use of the two strategies could in the future decrease the incidence of this neoplasm in PLHIV.

In summary, we believe that the design of this study inhibits us from defining the real utility of the strategy, bearing in mind, moreover, that CT scan adherence decreases progressively over time. In addition, we believe that the chosen CD4+ lymphocyte nadir was a limiting factor in selecting the study population, as it probably excluded patients who could have benefited from screening, as found by the study conducted by Makinson et al.,30 who set the nadir threshold at 350 CD4+ lymphocytes/mm3. However, in our study a lower CD4+ nadir was observed among subjects who developed LC, so it cannot be ruled out that significant differences may have been observed between patients who developed LC and those who did not according to CD4+ lymphocyte nadir in a study with a larger number of patients. As with other neoplasms, the inclusion criteria for PLHIV in a LC screening programme should be at least equivalent to the criteria applied to the general population where it is covered by the National Health System, taking into account that tobacco use is higher in this population, the age of onset of LC is earlier and tumours may behave more aggressively, especially in highly immunocompromised patients. Diagnosis of other conditions is very common, which could lead to closer monitoring of these PLHIV. Finally, including patients who smoke in a protocol for early LC diagnosis could support smoking cessation.

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.