To assess the degree of implementation of cancer screening recommendations in people living with HIV (PLHIV) in Spain.

MethodsA self-administered questionnaire was designed on the strategies used for early detection of the main types of cancer in PLHIV. The survey was distributed electronically to HIV physicians participating in the Spanish CoRIS cohort.

Results106 questionnaires were received from 12 different Spanish Autonomous Communities, with an overall response rate among those who accessed the questionnaire of 60.2%. The majority responded that they followed the CPGs recommendations for the early detection of liver (94.3%), cervical (93.2%) and breast (85.8%) cancers. In colorectal and anal cancer, the proportion was 68.9% and 63.2%, and in prostate and lung cancer of 46.2% and 19.8%, respectively. In hospitals with a greater number of beds, a tendency to perform more cancer screening and greater participation of the Infectious Diseases/HIV Services in the screening programmes was observed. Significant differences were observed in the frequency of colorectal and anal cancer screening among the different Autonomous Communities. The most frequent reasons for not performing screening were the scarcity of material and/or human resources and not being aware of what is recommended in the CPGs.

ConclusionsThere are barriers and opportunities to expand cancer screening programmes in PLHIV, especially in colorectal, anal and lung cancers. It is necessary to allocate resources for the early detection of cancer in PLHIV, but also to disseminate CPGs screening recommendations among medical specialists.

Conocer el grado de aplicación de las recomendaciones de cribado de cáncer en personas con VIH (PCVIH) en España.

MétodosSe diseñó un cuestionario autoadministrado sobre las estrategias empleadas para la detección precoz de los principales tipos de cáncer en PCVIH. La encuesta se distribuyó electrónicamente entre los médicos vinculados a la cohorte nacional CoRIS.

ResultadosSe recibieron 106 cuestionarios procedentes de 12 CC.AA, con una tasa global de respuesta entre los que accedieron al cuestionario del 60,2%. La mayoría respondieron que seguían las recomendaciones de las GPC para la detección precoz de los cánceres de hígado (94,3%), cérvix (93,2%) y mama (85,8%). En el cáncer colorrectal y anal la proporción fue del 68,9% y 63,2%, y en el de próstata y pulmón del 46,2% y 19,8%, respectivamente. En hospitales con mayor número de camas se observó una tendencia a realizar más cribados y una mayor participación de las Unidades de Enfermedades Infecciosas/VIH en el cribado. Se observaron diferencias significativas en la frecuencia de cribados de cáncer colorrectal y anal entre las CC.AA. Las razones más frecuentes para no realizar cribado fueron la escasez de recursos materiales y/o humanos y la falta de información sobre las recomendaciones en las GPC.

ConclusionesExisten barreras y oportunidades para extender los programas de cribado de cáncer en las PCVIH, especialmente en los cánceres colorrectal, anal y pulmonar. Se necesita asignar recursos para el diagnóstico precoz del cáncer en las PCVIH, pero también difundir las recomendaciones de cribado entre los médicos especialistas.

Cancer incidence and mortality rates are higher in people living with HIV (PLHIV) than in the general population, and the diagnosis is often made at younger ages and/or at more advanced stages.1–5 The excess risk is attributed to HIV immunosuppression, a higher prevalence of viral co-infections such as those caused by hepatitis C and B virus or human papillomavirus, and lifestyle factors such as smoking.1 Non-AIDS-defining cancers (NADC) are already the leading cause of death in PLHIV and are expected to become increasingly important as they age.6

The aim with early diagnosis of cancer is to detect the disease at an early stage, when treatment is most effective. Currently, European clinical practice guidelines (CPG) recommend various strategies for the early detection of some types of cancer in PLHIV, recommendations which for most cancers are based on international studies showing a reduction in morbidity and mortality rates in the general population.7,8 However, there is little data on the implementation of the proposed screening programmes and methods used in clinical practice in PLHIV.

To explore the situation in Spain, a national survey was conducted among clinicians with expertise in HIV/AIDS to find out the degree of implementation of screening recommendations, the strategies employed and the barriers to incorporating early cancer detection into the healthcare of PLHIV perceived by healthcare professionals.

MethodsPopulation and questionnaireWe invited physicians specialising in HIV/AIDS from Spanish health centres linked to the Cohorte de la Red Nacional de Investigación en sida (CoRIS) [Spanish National AIDS Research Network cohort] to take part in the study. CoRIS is a multicentre cohort established in 2004, which includes PLHIV treated in Infectious Diseases/HIV Units/Services (ID/HIVU) in 13 of the 17 autonomous regions (AR) of the Spanish National Health Service and is considered highly representative of Spain as a whole.9

The study coordinators designed an anonymised 14-question, multiple-choice questionnaire which included questions about the workplace (geographical location, number of beds and number of PLHIV under follow-up), the practice or not of screening and the screening strategy used for the following types of cancer: cervical, anal, lung, breast, colorectal, prostate and liver. For each type of cancer, if the strategy implemented was not that recommended in the CPG, they were asked for reasons and about barriers to implementing the strategy considered optimal. It was estimated that the survey would take 10−15 min to complete.

Distribution of the questionnaireThe survey was distributed via the Mailmeteor® platform [https://mailmeteor.com/es/] through the server of the Miguel Hernández University of Alicante [Google Workspace] to the professional emails on the distribution list of doctors linked to CoRIS. A single invitation to participate was issued on 20 March 2023 without subsequent reminders and we accepted responses received within two weeks. The survey was anonymous and did not collect any data that could identify the participants (see additional material).

Statistical analysisThe responses were exported to Microsoft Excel 2017 for computer processing and were analysed statistically with R software (R-Core Team 2023, R-4.3.0). Qualitative variables were described using frequency tables and percentage distribution. The chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used to compare proportions.

Ethical considerationsThe study was conducted in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Data confidentiality was ensured at all times. Participation in the study was voluntary.

ResultsA total of 298 emails were sent out; 231 were opened by the recipients and 176 of them accessed the link to the questionnaire. Within seven days of the invitation being sent out, 106 correctly completed questionnaires were received from doctors in 12 AR, with an overall response rate among those who accessed the questionnaire of 60.2%. The origin of the questionnaires received and the workplace characteristics are summarised in Table 1. The Autonomous Regions most represented were Madrid (n = 37; 34.9%), Andalusia (n = 16; 15.1%), Valencia (n = 14; 13.2%), Catalonia (n = 11; 10.4%), Basque Country (n = 10; 9.4%) and Murcia (7; 6.6%). Most of the surveys answered were from hospitals with 500−1000 beds (47.2%), followed by centres with fewer than 500 beds (27.4%) and those with more than 1000 beds (25.5%); 65 (61.3%) of the 106 respondents worked in hospitals with more than 1000 PLHIV, 30 (38.3%) in hospitals with 500−1000 PLHIV and 11 (10.4%) in hospitals with <500 PLHIV under follow-up.

Origin of the questionnaires received and characteristics of the workplaces of the doctors who completed the survey (n = 106).

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Autonomous region | |

| Andalusia | 16 (15.1) |

| Asturias | 1 (0.9) |

| Balearic Islands | 1 (0.9) |

| Canary Islands | 2 (1.9) |

| Catalonia | 11 (10.4) |

| Madrid Region | 37 (34.9) |

| Valencia Region | 14 (13.2) |

| Galicia | 4 (3.8) |

| Rioja | 4 (1.9) |

| Murcia | 7 (6.6) |

| Navarre | 1 (0.9) |

| Basque Country | 10 (9.4) |

| No. of hospital beds | |

| <500 | 27 (27.4) |

| ≥500 | 77 (72.6) |

| No. of people with HIV under follow-up | |

| ≤500 | 11 (10.4) |

| 500–1000 | 30 (28.3) |

| ≥1000 | 65 (61.3) |

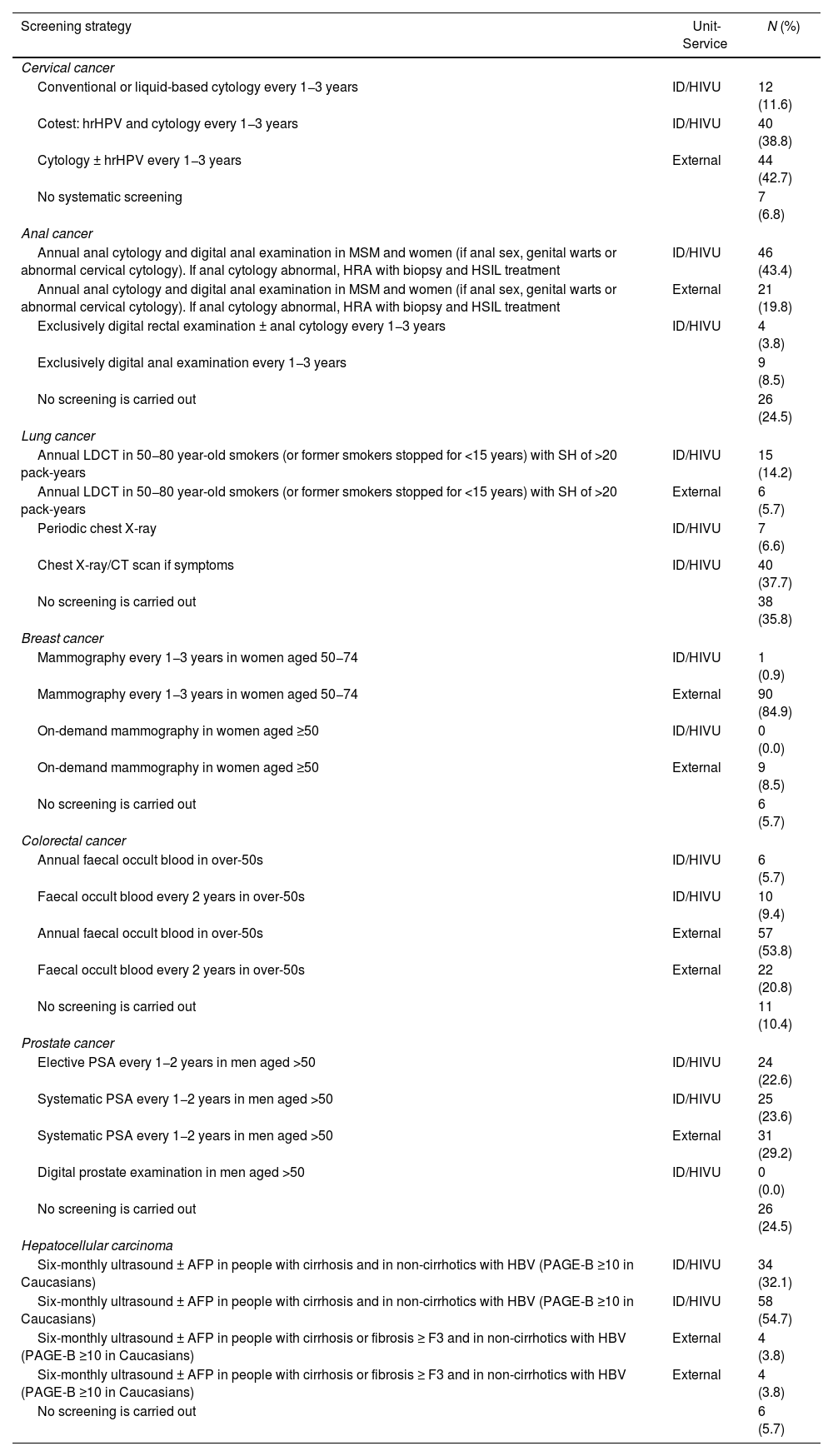

The majority of respondents answered that the PLHIV seen in their practice regularly followed CPG recommendations for the early detection of liver (100/106; 94.3%), cervical (95/103; 93.2%) and breast (91/106; 85.8%) cancers. The proportion of PLHIV following recommended screening strategies for colorectal cancer was 68.9% (73/106), for anal cancer, 63.2% (67/106), prostate cancer, 46.2% (49/106) and lung cancer, 19.8% (21/106). The screening methods used for each of the cancers are detailed in Table 2.

Cancer screening strategies performed in people with HIV seen at the workplaces of the physicians who completed the survey (n = 106) and services where screening is performed.

| Screening strategy | Unit-Service | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical cancer | ||

| Conventional or liquid-based cytology every 1−3 years | ID/HIVU | 12 (11.6) |

| Cotest: hrHPV and cytology every 1−3 years | ID/HIVU | 40 (38.8) |

| Cytology ± hrHPV every 1−3 years | External | 44 (42.7) |

| No systematic screening | 7 (6.8) | |

| Anal cancer | ||

| Annual anal cytology and digital anal examination in MSM and women (if anal sex, genital warts or abnormal cervical cytology). If anal cytology abnormal, HRA with biopsy and HSIL treatment | ID/HIVU | 46 (43.4) |

| Annual anal cytology and digital anal examination in MSM and women (if anal sex, genital warts or abnormal cervical cytology). If anal cytology abnormal, HRA with biopsy and HSIL treatment | External | 21 (19.8) |

| Exclusively digital rectal examination ± anal cytology every 1−3 years | ID/HIVU | 4 (3.8) |

| Exclusively digital anal examination every 1−3 years | 9 (8.5) | |

| No screening is carried out | 26 (24.5) | |

| Lung cancer | ||

| Annual LDCT in 50−80 year-old smokers (or former smokers stopped for <15 years) with SH of >20 pack-years | ID/HIVU | 15 (14.2) |

| Annual LDCT in 50−80 year-old smokers (or former smokers stopped for <15 years) with SH of >20 pack-years | External | 6 (5.7) |

| Periodic chest X-ray | ID/HIVU | 7 (6.6) |

| Chest X-ray/CT scan if symptoms | ID/HIVU | 40 (37.7) |

| No screening is carried out | 38 (35.8) | |

| Breast cancer | ||

| Mammography every 1−3 years in women aged 50−74 | ID/HIVU | 1 (0.9) |

| Mammography every 1−3 years in women aged 50−74 | External | 90 (84.9) |

| On-demand mammography in women aged ≥50 | ID/HIVU | 0 (0.0) |

| On-demand mammography in women aged ≥50 | External | 9 (8.5) |

| No screening is carried out | 6 (5.7) | |

| Colorectal cancer | ||

| Annual faecal occult blood in over-50s | ID/HIVU | 6 (5.7) |

| Faecal occult blood every 2 years in over-50s | ID/HIVU | 10 (9.4) |

| Annual faecal occult blood in over-50s | External | 57 (53.8) |

| Faecal occult blood every 2 years in over-50s | External | 22 (20.8) |

| No screening is carried out | 11 (10.4) | |

| Prostate cancer | ||

| Elective PSA every 1−2 years in men aged >50 | ID/HIVU | 24 (22.6) |

| Systematic PSA every 1−2 years in men aged >50 | ID/HIVU | 25 (23.6) |

| Systematic PSA every 1−2 years in men aged >50 | External | 31 (29.2) |

| Digital prostate examination in men aged >50 | ID/HIVU | 0 (0.0) |

| No screening is carried out | 26 (24.5) | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | ||

| Six-monthly ultrasound ± AFP in people with cirrhosis and in non-cirrhotics with HBV (PAGE-B ≥10 in Caucasians) | ID/HIVU | 34 (32.1) |

| Six-monthly ultrasound ± AFP in people with cirrhosis and in non-cirrhotics with HBV (PAGE-B ≥10 in Caucasians) | ID/HIVU | 58 (54.7) |

| Six-monthly ultrasound ± AFP in people with cirrhosis or fibrosis ≥ F3 and in non-cirrhotics with HBV (PAGE-B ≥10 in Caucasians) | External | 4 (3.8) |

| Six-monthly ultrasound ± AFP in people with cirrhosis or fibrosis ≥ F3 and in non-cirrhotics with HBV (PAGE-B ≥10 in Caucasians) | External | 4 (3.8) |

| No screening is carried out | 6 (5.7) |

AFP: alpha-fetoprotein; CT: computed axial tomography; F3: fibrosis 3; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HRA: high-resolution anoscopy; hrHPV: high-risk human papilloma virus; HSIL: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; ID/HIVU: Infectious Diseases/HIV services or units; LDCT: low-dose computed tomography; MSM: men who have sex with men; PAGE-B: hepatocarcinoma risk scale based on platelet count, age and gender; SM: smoking history.

In terms of the units or services where cancer screening was carried out, respondents indicated that ID/HIVU were directly involved in screening programmes for liver (92/106; 86.8%), cervical (52/103; 50.5%), prostate (49/106; 46.2%), anal (46/106; 43.4%) and lung (15/106; 14.1%) cancers, while colorectal and breast cancer screening was mostly performed in Public Health Services.

There was no difference in the proportion of screenings carried out according to the number of PLHIV under follow-up at the centres where the respondents worked (data not shown). At hospitals with more than 500 beds there was a tendency to screen more frequently for cervical, anal, breast and prostate cancer than at smaller centres, and a greater involvement of ID/HIVU in screening programmes (Fig. 1A and B). Significant differences were found in the frequency of screening for colorectal and anal cancer according to the autonomous region in which respondents worked (Fig. 2).

(A) Frequency of cancer screening in people with HIV according to the number of beds (<500 vs >500) in the hospital where the doctors who completed the questionnaire (n = 106) worked.

Values expressed as n (%). (*) p < 0.05 for the difference in the proportion of people screened according to the number of beds.

(B) Cancer screenings in people with HIV performed directly in the centre's Infectious Diseases/HIV Units/Services (ID/HIVU) according to the number of beds (<500 vs >500) in the hospital where the doctors who completed the questionnaire (n = 106) worked. Values expressed as n (%).

CPG: clinical practice guidelines.

Frequency of screening for colorectal and anal cancer in people with HIV according to the autonomous region in which the doctors who completed the questionnaire (n = 106) worked. CPG: clinical practice guidelines. Values expressed as n (%). (*) p < 0.05 for the difference in the frequency of screening between Autonomous Regions.

Among the reasons for not implementing screening strategies considered to be optimal, the most common was a lack of material or human resources, followed by the lack of recommendation for such a strategy in the CPG, with this being the reason given by 34.6% of respondents for prostate cancer screening, 20% for breast cancer, 16% for lung cancer and 12% for colorectal cancer (Fig. 3).

DiscussionThe results of the study indicate that the majority of PLHIV seen in the clinics of the responding physicians are regularly screened for liver, cervical and breast cancer. However, the level of implementation of colorectal, anal and lung cancer screening is still low. Screening for breast and colorectal cancer is mostly carried out within the framework of the population-based programmes included in the Spanish National Health Service's common portfolio of services. In contrast, liver cancer screening is predominantly performed in ID/HIVU, which also contribute significantly to anal, cervical, prostate and lung cancer screening. The main barrier perceived by the surveyed doctors to incorporating early detection of some types of cancer into the healthcare of PLHIV is the lack of material and/or human resources.

Early diagnosis is one of the priority objectives of the European Cancer Plan, which aims for Member States to reach the goal of 90% of the population having access to screening for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer by 2025.10 Spain has population-based screening programmes for the early diagnosis of breast and colorectal cancer, although they are not evenly implemented in all parts of the country.11,12 Breast cancer screening has broad national coverage with a high degree of participation in all the Autonomous Regions. The results of this survey show that PLHIV generally have access to this programme, although participation is below 90% and tends to be lower in smaller centres. Unlike breast cancer, colorectal cancer screening is still in the implementation phase in some AR.13 The data provided by the doctors surveyed in this study put the participation of PLHIV below 70%, with significant differences between the different AR, with this figure being lower than the programme's coverage at a national level.13

The respondents indicate that ID/HIVU are actively involved in screening for the cancers most closely associated with HIV infection and viral co-infections, such as liver, cervical and anal cancers. Liver cancer is the second most common NADC in PLHIV14 and the second most common cause of death related to NADC.15 The survey shows that in the majority of PLHIV, liver screening is performed directly in the ID/HIVU and the preferred screening method of the survey respondents is six-monthly ultrasound ± alpha-fetoprotein determination in patients with cirrhosis or fibrosis ≥ F3 and in non-cirrhotics with hepatitis B virus PAGE ≥ 10, with this continuing to be the main strategy recommended in the CPG, despite little evidence to support its efficacy in detecting early stage cancers in PLHIV.5

In the case of cervical cancer, the specialists surveyed indicated that ID/HIVU were involved in one in every two screenings, giving preference to the so-called "cotest", a joint test for molecular detection of human papillomavirus and cervical cytology every 1−3 years. Although a population-based screening programme has recently been launched in Spain, cervical cancer screening has so far been offered to women aged 25–65 on an opportunistic basis, with cervical cytology every 3–5 years. This strategy is considered suboptimal in HIV-positive women, who are a high-risk group, with guidelines recommending earlier and more frequent screening than in the general population.7,16,17

An unexpected finding of the survey was that more than 60% of PLHIV seen by the surveyed physicians are already screened for anal cancer, with marked differences between AR. Of all NADC, anal cancer has the highest excess incidence and mortality rate2,18 and it is the leading NADC in years of life lost in PLHIV in the USA.19 The natural history of anal cancer can be modified by early treatment of the high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, which is a precursor to invasive carcinoma.20 To date, there is no international consensus on anal cancer screening, although the results of the recently published ANCHOR trial21 suggest that screening and treatment of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions should be incorporated as a routine procedure among cancers detectable by screening in PLHIV at increased risk of anal cancer.

Only one in five PLHIV seen in the participating doctors' clinics were screened for lung cancer, a very low figure considering that lung cancer is the most common NADC and the leading cause of cancer-related death in PLHIV.14 Lung cancer screening programmes based on low-radiation dose computed tomography have strong scientific evidence, have been implemented in some countries for lung cancer screening in the general high-risk population22,23 and are recommended by the European AIDS Society for PLHIV.7 Unfortunately, in Spain this screening programme has not yet been implemented in the National Health Service. This is probably hindering the early diagnosis of lung cancer in PLHIV, a particularly vulnerable group, in which the incidence is twice that of the general population2; lung cancer also occurs at younger ages in PLHIV and the mortality rate is up to four times higher,2,24 probably for being at an advanced stage at the time of diagnosis.

One of the aims of the study was to find out the reasons for screening not being carried out. Although the main barrier perceived by the doctors surveyed was the lack of material and/or human resources, a significant proportion of respondents answered that they did not screen due to the lack of scientific evidence for colorectal or breast cancer, diseases where early diagnosis is well proven to reduce morbidity and mortality rates and population screening is widely recommended.

The main limitations of the study derive from the sample studied and the type of questionnaire used. All the participating doctors worked in facilities linked to the coRIS and a high proportion were in medium to large hospitals with a significant number of PLHIV under follow-up, so it may not be possible to generalise the results to other settings where PLHIV might receive care. The territorial distribution of the respondents was related to the degree of connection the different AR have with the coRIS and does not necessarily represent the number of PLHIV seen in each case. Furthermore, as the survey was completed anonymously and no data was collected that would enable respondents to be identified, we cannot be sure that the centres the participants who completed the survey were attached to represent the CoRIS universe. The questionnaire model with closed questions and answers within a limited framework of options may have encouraged respondents to choose options considered desirable or optimal in some cases. Some of the centres where the respondents work are involved in a multi-centre clinical trial evaluating two cancer screening strategies, which may also have influenced their choice of answers.25 Moreover, respondents were not asked about the frequency with which they carried out screening, meaning we were not able to estimate the degree of participation of PLHIV in each type of screening and, even less so, the degree of adherence to screening, which in general tends to be suboptimal in screening by clinicians caring for PLHIV,26 and lower than in non-infected people in population-based screening.27–29 Lastly, the questions were only put to the doctors and the perspective of the patients, whose views on barriers to the implementing of screening programmes may differ from those of the healthcare workers, was not assessed.30

In summary, the study reports on the status of cancer screening in PLHIV in Spain and identifies barriers to, and opportunities for expanding, cancer screening programmes in people living with HIV, especially for colorectal, anal and lung cancer. The results highlight the need to allocate structural and human resources for the early diagnosis of cancer in PLHIV, but also to foster a more in-depth understanding and widespread dissemination of screening recommendations among medical specialists. Specific messages about the efficacy and benefits of early cancer detection in PLHIV would improve the uptake and adoption of screening programmes by healthcare professionals, as well as the participation and adherence of people living with virus.

FundingThis work was supported by projects RD16/0025/0038 and CB21/13/00011 of the Plan Nacional de Investigación+Desarrollo+Innovación (I+D+I) [Spanish National Plan for Research, Development and Innovation] of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III - European Regional Development Fund (grants PI16/01740, PI18/01861, CM19/00160, CM20/00066, CM21/00186) and the Conselleria de Innovación, Universidades y Ciencia de la Generalitat Valenciana [Valencian Regional Government Department of Innovation, Universities and Science] (AICO/2021/205).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The study would not have been possible without the selfless collaboration of all the doctors who participated in the project by completing the survey.

500) in the hospital where the doctors who completed the questionnaire (n = 106) worked. Values expressed as n (%). CPG: clinical practice guidelines.' title='(A) Frequency of cancer screening in people with HIV according to the number of beds (<500 vs >500) in the hospital where the doctors who completed the questionnaire (n = 106) worked. Values expressed as n (%). (*) p < 0.05 for the difference in the proportion of people screened according to the number of beds. (B) Cancer screenings in people with HIV performed directly in the centre's Infectious Diseases/HIV Units/Services (ID/HIVU) according to the number of beds (<500 vs >500) in the hospital where the doctors who completed the questionnaire (n = 106) worked. Values expressed as n (%). CPG: clinical practice guidelines.'/>

500) in the hospital where the doctors who completed the questionnaire (n = 106) worked. Values expressed as n (%). CPG: clinical practice guidelines.' title='(A) Frequency of cancer screening in people with HIV according to the number of beds (<500 vs >500) in the hospital where the doctors who completed the questionnaire (n = 106) worked. Values expressed as n (%). (*) p < 0.05 for the difference in the proportion of people screened according to the number of beds. (B) Cancer screenings in people with HIV performed directly in the centre's Infectious Diseases/HIV Units/Services (ID/HIVU) according to the number of beds (<500 vs >500) in the hospital where the doctors who completed the questionnaire (n = 106) worked. Values expressed as n (%). CPG: clinical practice guidelines.'/>