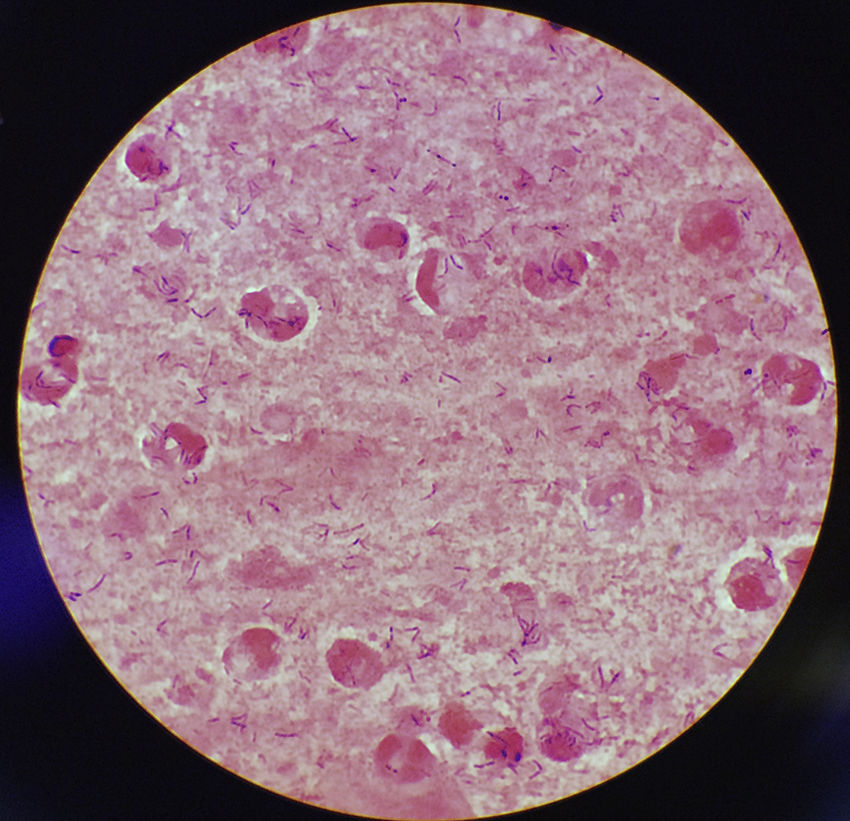

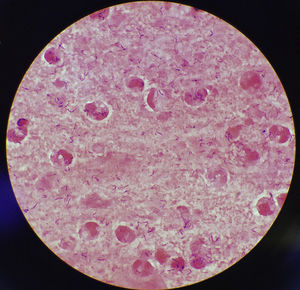

This case discusses a 77-year-old woman who went to her primary care doctor with a sore throat, cough, drowsiness, greenish sputum and afebrile (36.7°C). She presented as history of interest diabetes mellitus secondary to steroid treatment and bronchiectasis. Her recent vaccination record included the flu vaccine and tetanus–diphtheria vaccine, which was administered in 2003. She had no history of contact with animals or recent travel. A sample of sputum was collected for culture and abundant leukocytes and Gram-positive bacilli were observed in the Gram stain (Fig. 1). After 24h of incubation, in Columbia CNA agar with 5% sheep blood and chocolate agar, very small pure colonies were isolated in culture (∼1mm diameter), catalase-positive, grey and shiny with a small area of beta-haemolysis. The microorganism was identified as Corynebacterium diphtheriae (C. diphtheriae) biotype mitis/belfanti using API Coryne (bioMérieux; BioNumber 0000324; 90.2%) and MALDI-TOF (MALDI Biotyper® Microflex LT, Bruker Daltonik GmbH; score: 1786). The gene coding for subunit β of RNA polymerase (rpoB) was sequenced, confirming this identification.1 The presence of the diphtheria toxin gene (tox) was not detected using PCR2 and its expression was not detected either using the Elek test.3 Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined using the ɛ-test method (bioMérieux) and interpreted according to the recommendations established by the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI] (www.clsi.org). The minimum inhibitory concentrations (μg/ml) were: penicillin (0.25, susceptible [S]), cefotaxime (1.5, intermediate [I]), cefepime (1.5, I), imipenem (0.125, S), meropenem (0.064, S), erythromycin (0.016, S), ciprofloxacin (>32, resistant), tetracycline (0.75, S), clindamycin (0.25, S), co-trimoxazole (0.064, S), rifampicin (0.002, S), and linezolid (0.25, S). Antibiotic treatment was also established with erythromycin 500mg/day for 14 days with favourable progression.

Since 1986, three articles have been published in Spain on respiratory and cutaneous diphtheria due to toxigenic and/or non-toxigenic (NT) strains.4–6 This is the first documented case of respiratory diphtheria caused by biotype belfanti NT in Spain. The main reservoir of C. diphtheriae is humans. However, both types of strains have been isolated in domestic, and even wild, animals with no evidence of zoonotic transmission.7

C. diphtheriae is made up of four biotypes: gravis, mitis, intermedius, and belfanti. The biotype belfanti presents respiratory tropism taking advantage at the time of colonising or infecting the upper respiratory tract compared to other biotypes, being described fundamentally in cases of primary chronic atrophic rhinitis (ozaena).8 It has been isolated most frequently in geographic areas with a high vaccine coverage, such as North America and Europe (36–100%). During the post-epidemic period, its presence has been increasing in Europe replacing the toxigenic strains, which belong mostly to the biotypes gravis and mitis.9,10 The NT strains can cause severe infections such as myocarditis, endocarditis, bacteraemia, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, neuritis and epiglottitis.8–10 Its mechanism of pathogenicity is still not understood and little is known about the genes responsible for colonisation, invasion and survival in the host, as well as about other virulence factors aside from the production of the toxin.

MALDI-TOF has been described as a useful, cost-effective and rapid tool for the identification of this microorganism along with other toxigenic species such as Corynebacterium ulcerans and Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, although it is not able to differentiate toxigenic strains from NT stains.11 In addition, the sequencing of the gene rpoB has demonstrated greater discriminatory power (91%) than the sequencing of 16S rRNA (81%).12 These methods should always be accompanied by the detection and expression of the tox gene, with the absence of diphtheria toxin being something common in the biotype belfanti, which has demonstrated great clonal diversity compared to the other biotypes.9,10

Over the years, an increase in the antimicrobial resistance of NT strains has been observed. C. diphtheriae biotype belfanti tends to present greater susceptibility than the other biotypes. However, reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, cefotaxime and cefepime has been reported. These are not considered to be good treatment options. Erythromycin or penicillin are the treatment of choice, with both not being effective in some cases due to the description of resistant strains.8–10

This case demonstrates the need to monitor the spreading of C. diphtheriae strains circulating in Spain; not only those strains which are toxigenic, but also the NT strains which should be considered emerging pathogens.

The authors would like to thank Silvia Herrera León from the Spanish National Microbiology Centre of Majadahonda (ISCIII) for carrying out the characterisation of the isolation.

Please cite this article as: Barrado L, Beristain X, Martín-Salas C, Ezpeleta-Baquedano C. Corynebacterium diphtheriae biotipo belfanti no toxigénico en una paciente diabética con infección del tracto respiratorio superior. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eimc.2018.10.005