To analyze the characteristics of patients with nosocomial flu, to compare them with patients with community-acquired influenza to study possible differences and to identify possible risk factors associated with this type of flu.

Patients and methodsObservational, cross-sectional and retrospective study of hospitalized patients with a microbiological confirmation of influenza in a third-level university hospital over 10 seasons, from 2009 to 2019. Nosocomial influenza was defined as that infection whose symptoms began 72h after hospital admission, and its incidence, characteristics and consequences were further analyzed.

ResultsA total of 1260 hospitalized patients with a microbiological diagnosis of influenza were included, which 110 (8.7%) were nosocomial. Patients with hospital-acquired influenza were younger (71.74±16.03 years, P=0.044), had a longer hospital stay (24.25±20.25 days, P<0.001), had more frequently a history of chronic pulmonary pathologies (P=0.010), immunodeficiency (P<0.001), and were associated with greater development of bacterial superinfection (P<0.001), respiratory distress (P=0.003), and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) (P<0.001). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the following characteristics were identified as independent risk factors: immunodeficiency (ORa=2.33; 95% CI: 1.47–3.60); ICU admission (ORa=4.29; 95% CI: 2.23–10.91); bacterial superinfection (ORa=1.64; 95% CI: 1.06–2.53) and respiratory distress (ORa=3.88; 95% CI: 1.23–12.23).

ConclusionsNosocomial influenza is more common in patients with a history of immunodeficiency. In addition, patients with hospital-acquired influenza had an increased risk of bacterial superinfection, admission to the ICU, and development of respiratory distress.

Analizar las características de los pacientes con gripe nosocomial, compararlas con las de los enfermos con diagnóstico de gripe comunitaria para estudiar posibles diferencias e identificar posibles factores de riesgo asociados a este tipo de gripe.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio observacional, transversal y retrospectivo de los pacientes hospitalizados con diagnóstico microbiológico de gripe en un hospital universitario de tercer nivel durante 10 temporadas, de 2009 a 2019. Se definió como gripe nosocomial aquella infección cuyos síntomas comenzaron 72h después del ingreso hospitalario y se analizó su incidencia, características y consecuencias.

ResultadosSe incluyó a un total de 1.260 pacientes hospitalizados con diagnóstico microbiológico de gripe, de los cuales 110 (8,7%) fueron nosocomiales. Los pacientes con gripe adquirida en el hospital eran más jóvenes (71,74±16,03 años; p=0,044), tuvieron una estancia hospitalaria mayor (24,25±20,25 días; p<0,001), tenían con mayor frecuencia antecedentes de enfermedades pulmonares crónicas (p=0,010), inmunodeficiencias (p<0,001) y se asociaron con mayor desarrollo de sobreinfección bacteriana (p<0,001), distrés respiratorio (p=0,003) e ingreso en la unidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI) (p<0,001). En el análisis por regresión logística multivariante se identificaron como factores de riesgo independientes: inmunodeficiencia (ORa=2,33; IC 95%: 1,47−3,60); ingreso en UCI (ORa=4,29; IC 95%: 2,23−10,91); desarrollo de sobreinfección bacteriana (ORa=1,64; IC 95%: 1,06−2,53) y de distrés respiratorio (ORa=3,88; IC 95%: 1,23−12,23).

ConclusionesLa gripe nosocomial es más frecuente en los pacientes con antecedentes de inmunodeficiencia. Además, los enfermos con gripe hospitalaria tienen un riesgo aumentado de sobreinfección bacteriana, ingreso en UCI y desarrollo de distrés respiratorio.

Influenza is an infection that causes a significant number of hospital admissions each season.1 In a percentage of cases, an adequate diagnosis of the infection is not made, particularly among those with hospital-acquired influenza. Moreover, the problem of hospital-acquired influenza is attracting increasingly greater epidemiological interest since it has been associated with high morbidity and mortality and increased financial costs due to longer hospital stays.2

Various outbreaks of influenza have been studied in different hospitals and over several seasons3–6, but there is no utterly reliable information in this regard because case-reporting and follow-up is frequently unstructured.7 This lack of correct identification of influenza cases and the failure to implement stricter hospital infection control rules puts patients and healthcare workers at risk of contracting hospital-acquired influenza. Although only limited data are currently available on the true burden of hospital-acquired influenza, it could be potentially serious in patients with comorbidities, pregnant women or the elderly. Furthermore, its impact on healthcare worker absenteeism can be devastating, as the workload is particularly high during influenza seasons in most hospitals.8

Therefore, we believe that the analysis of hospital-acquired influenza provides data of epidemiological, clinical and economic interest, prompting us to propose the evaluation of the impact of this type of influenza and its consequences with the following objectives: to analyse the demographic, clinical and microbiological characteristics of patients with hospital-acquired influenza; to compare them to those of patients diagnosed with community-acquired influenza to study possible differences and to identify risk factors associated with this type of influenza.

Patients and methodsStudy design and data sourceThis is an observational, cross-sectional and retrospective study of patients admitted with a diagnosis of influenza in a tertiary university hospital during the 2009–2010 influenza pandemic and in the 2010–2011, 2011–2012, 2012–2013, 2013–2014, 2014–2015, 2015–2016, 2016–2017, 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 influenza seasons. The data were collected using the clinical history and mandatory reporting documents. The hospital has 1250 beds, it is located in the north of the city of Madrid and is one of the sentinel hospitals of the influenza epidemiological surveillance network of the Autonomous Community of Madrid.9 This system describes the clinical-epidemiological characteristics of the so-called “hospitalised cases of severe laboratory-confirmed influenza”, which are the cases that present clinical symptoms consistent with influenza, require hospitalisation due to their severity (pneumonia, respiratory distress, multiple organ failure, admission to the intensive care unit [ICU] or death during the hospital stay) and have a microbiological laboratory confirmation. Reporting requires the completion of a questionnaire for each case, which gathers sociodemographic data, symptoms, disease risk factors, complications, evolution, treatment and case classification. The professionals tasked with carrying out this epidemiological work comprise the “influenza working group”, which involves the collaboration of clinical teams from different specialties, nursing professionals, microbiologists and preventive specialists.

Study variablesAll patients over 18 years of age hospitalised for influenza microbiologically confirmed by polymerase chain reaction in nasopharyngeal exudate10 during the 2009–2010 influenza pandemic and in the 9 successive epidemic influenza seasons (2010–2019) were included.

Hospital-acquired influenza was defined as an infection whose symptoms began 72h after hospitalisation.

The patients' baseline characteristics, such as age, sex, hospital stay, and vaccination status, were collected. Comorbidities that may be a risk factor for influenza were also collected, such as the existence of chronic lung disease, heart disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, any type of immunodeficiency (cancer patients on treatment with chemotherapy, biologic therapies or immunosuppressive treatment, solid organ transplant recipients and HIV-infected patients), morbid obesity (body mass index >40kg/m2), liver disease and pregnancy. Furthermore, the factors that conditioned a serious prognosis were identified, such as the development of secondary bacterial pneumonia (consistent clinical symptoms and the emergence of a new infiltrate in the chest X-ray11); complication with secondary bacterial superinfection other than pneumonia, evolution to multiple organ failure and the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and admission to the ICU. The patients who died during hospitalisation were also recorded. The antiviral treatment received, its duration and the type of influenza virus strain were other variables analysed.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the different study variables was performed. The data are presented as mean (standard deviation) or as a number (percentages). The qualitative variables were compared with the χ2 test after constructing different contingency tables, while the quantitative variables were compared with Student's t test. If the variables did not meet normality criteria, non-parametric tests were used. The odds ratio (OR) was used to study the risk of occurrence of hospital-acquired influenza, with an established confidence interval (CI) of 95%. First of all, a univariate regression analysis was carried out for each variable separately for the purpose of selecting those with a p<0.05. Subsequently, these variables were included in a multivariate logistic regression model to calculate the adjusted odds ratio (aOR). Differences with p<0.05 values were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was conducted with the SPSS statistical package, version IBM® SPSS® Statistics 23.0.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Medicines Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario La Paz (PI-2850).

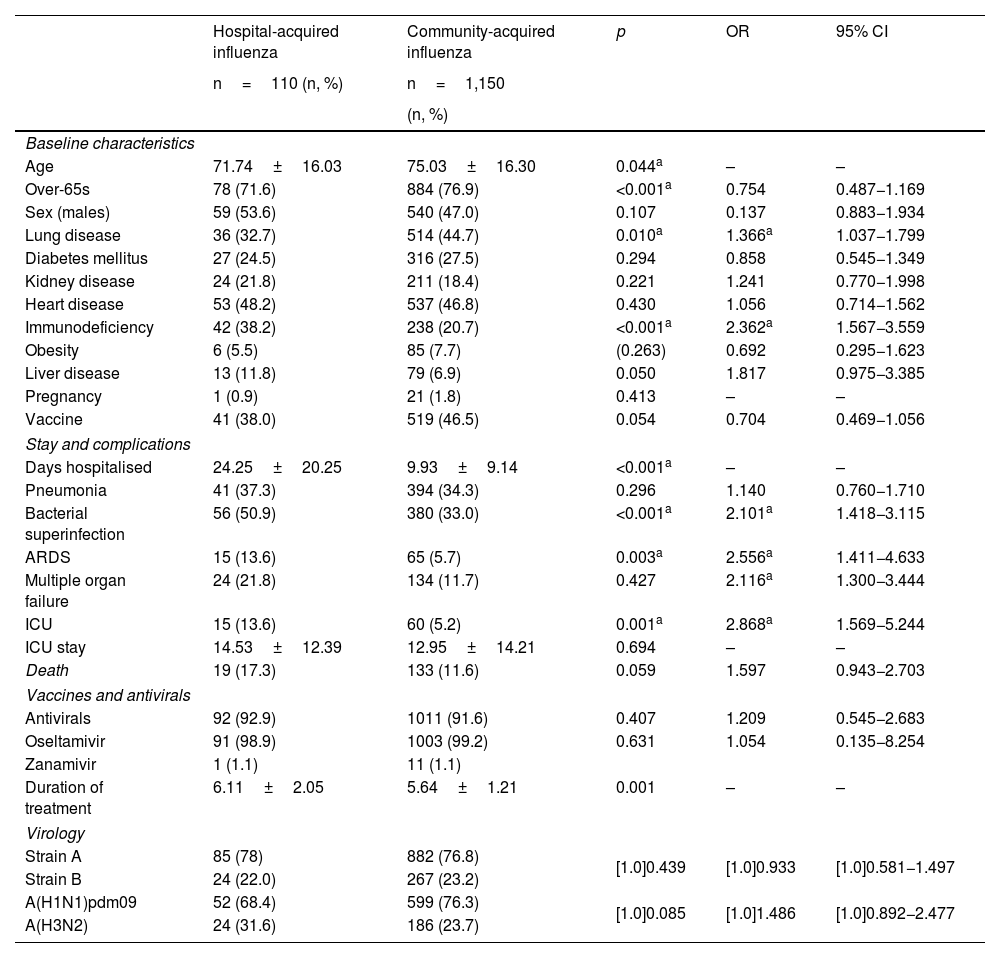

ResultsA total of 1260 patients were included in the study, 110 of whom were diagnosed with hospital-acquired influenza. These patients were compared with the 1150 patients admitted for community-acquired influenza (Table 1). The patients with hospital-acquired influenza were younger, with a mean age of 71.74±16.03 years (p=0.044). These patients also had a longer hospital stay compared to the patients with community-acquired influenza (24.25±20.25 days; p<0.001). Although there were no differences between the two groups in terms of vaccination, it bordered on the statistically significant, with lower coverage in patients with hospital-acquired influenza (38.0% vs. 46.5%; p=0.054).

Comparison of community-acquired influenza and hospital-acquired influenza.

| Hospital-acquired influenza | Community-acquired influenza | p | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=110 (n, %) | n=1,150 | ||||

| (n, %) | |||||

| Baseline characteristics | |||||

| Age | 71.74±16.03 | 75.03±16.30 | 0.044a | – | – |

| Over-65s | 78 (71.6) | 884 (76.9) | <0.001a | 0.754 | 0.487−1.169 |

| Sex (males) | 59 (53.6) | 540 (47.0) | 0.107 | 0.137 | 0.883−1.934 |

| Lung disease | 36 (32.7) | 514 (44.7) | 0.010a | 1.366a | 1.037−1.799 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 27 (24.5) | 316 (27.5) | 0.294 | 0.858 | 0.545−1.349 |

| Kidney disease | 24 (21.8) | 211 (18.4) | 0.221 | 1.241 | 0.770−1.998 |

| Heart disease | 53 (48.2) | 537 (46.8) | 0.430 | 1.056 | 0.714−1.562 |

| Immunodeficiency | 42 (38.2) | 238 (20.7) | <0.001a | 2.362a | 1.567−3.559 |

| Obesity | 6 (5.5) | 85 (7.7) | (0.263) | 0.692 | 0.295−1.623 |

| Liver disease | 13 (11.8) | 79 (6.9) | 0.050 | 1.817 | 0.975−3.385 |

| Pregnancy | 1 (0.9) | 21 (1.8) | 0.413 | – | – |

| Vaccine | 41 (38.0) | 519 (46.5) | 0.054 | 0.704 | 0.469−1.056 |

| Stay and complications | |||||

| Days hospitalised | 24.25±20.25 | 9.93±9.14 | <0.001a | – | – |

| Pneumonia | 41 (37.3) | 394 (34.3) | 0.296 | 1.140 | 0.760−1.710 |

| Bacterial superinfection | 56 (50.9) | 380 (33.0) | <0.001a | 2.101a | 1.418−3.115 |

| ARDS | 15 (13.6) | 65 (5.7) | 0.003a | 2.556a | 1.411−4.633 |

| Multiple organ failure | 24 (21.8) | 134 (11.7) | 0.427 | 2.116a | 1.300−3.444 |

| ICU | 15 (13.6) | 60 (5.2) | 0.001a | 2.868a | 1.569−5.244 |

| ICU stay | 14.53±12.39 | 12.95±14.21 | 0.694 | – | – |

| Death | 19 (17.3) | 133 (11.6) | 0.059 | 1.597 | 0.943−2.703 |

| Vaccines and antivirals | |||||

| Antivirals | 92 (92.9) | 1011 (91.6) | 0.407 | 1.209 | 0.545−2.683 |

| Oseltamivir | 91 (98.9) | 1003 (99.2) | 0.631 | 1.054 | 0.135−8.254 |

| Zanamivir | 1 (1.1) | 11 (1.1) | |||

| Duration of treatment | 6.11±2.05 | 5.64±1.21 | 0.001 | – | – |

| Virology | |||||

| Strain A | 85 (78) | 882 (76.8) | [1.0]0.439 | [1.0]0.933 | [1.0]0.581−1.497 |

| Strain B | 24 (22.0) | 267 (23.2) | |||

| A(H1N1)pdm09 | 52 (68.4) | 599 (76.3) | [1.0]0.085 | [1.0]1.486 | [1.0]0.892−2.477 |

| A(H3N2) | 24 (31.6) | 186 (23.7) | |||

Quantitative variables are expressed in terms of mean±standard deviation.

(n, %): number, percentage; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; p: statistical significance.

Regarding comorbidities, patients with hospital-acquired influenza had a higher frequency of chronic lung diseases (OR=1.36; 95% CI: 1.03–1.799) and immunodeficiencies (OR=2.36; 95% CI: 1.56–3.55) (Table 1).

Following the analysis of complications and poor prognostic factors, hospital-acquired influenza was found to be associated with a greater development of bacterial superinfection (OR=2.10; 95% CI: 1.42–3.12), admission to the ICU (OR=2.87; 95% IC: 1.57–5.24) and development of ARDS (OR=2.56; 95% IC: 1.41–4.63) (Table 1). We found no differences regarding other types of complications, including mortality, although it was higher among patients with hospital-acquired influenza, bordering on the statistically significant (p=0.059).

Neither did we find differences with regard to antiviral treatment or the type of influenza virus or its different strains.

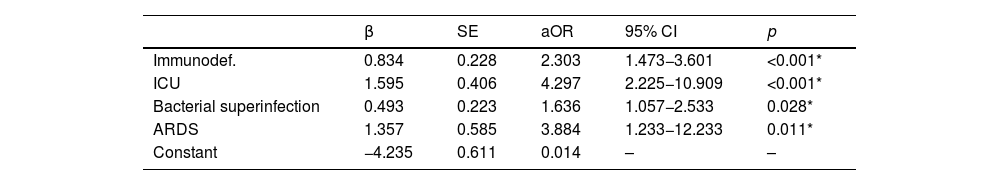

In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, a history of immunodeficiency (aOR=2.33; 95% CI: 1.47–3.60), admission to the ICU (aOR=4.29; 95% CI: 2.23–10.91), the development of bacterial superinfection (aOR=1.64; 95% CI: 1.06–2.53) and respiratory distress (aOR=3.88; 95% CI: 1.23–12.23) were identified as independent risk factors (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis, logistic regression Independent predictive factors for hospital-acquired influenza.

| β | SE | aOR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunodef. | 0.834 | 0.228 | 2.303 | 1.473−3.601 | <0.001* |

| ICU | 1.595 | 0.406 | 4.297 | 2.225−10.909 | <0.001* |

| Bacterial superinfection | 0.493 | 0.223 | 1.636 | 1.057−2.533 | 0.028* |

| ARDS | 1.357 | 0.585 | 3.884 | 1.233−12.233 | 0.011* |

| Constant | −4.235 | 0.611 | 0.014 | – | – |

β: regression coefficient; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; p: statistical significance; SE: standard error.

In our study, we found a total of 110 cases of hospital-acquired influenza, representing 8.7% of the total number of the influenza cases included in the protocol. In the related studies, the proportion of influenza classified as hospital-acquired varied from 4% to 23%8. This significant divergence in the frequency of hospital-acquired influenza in each study can be explained by several precepts: firstly, the definition of case of hospital-acquired influenza is not always the same, since the time between admission and the onset of symptoms varies from 48 to 96h12,13; secondly, it must be remembered that hospital-acquired infection control measures differ between countries and hospitals; thirdly, the microbiological characteristics of the circulating strains in each season are different; and finally, the percentage of vaccination coverage and its effectiveness is also highly variable. For example, Godoy et al.7, in their multicentre case-control article from 12 hospitals in Catalonia during the 2010–2016 seasons, reported a figure of 5.6% hospital-acquired influenza; on the other hand, in a study carried out at the Hospital de Salamanca during the 2016–2017 season, 14.3% cases of hospital-acquired influenza were detected.14 Finally, a Canadian study that analysed the 2007–2010 seasons confirmed 23.2% of hospital-acquired cases of influenza diagnosed in the 51 hospitals included in the project.13

Furthermore, we observed that patients with hospital-acquired influenza were younger than those with community-acquired influenza, with a mean age of 71 years. These data differ from the data published by different authors7,8, in which patients with hospital-acquired influenza are older. It is true that the mean age of patients with hospital-acquired influenza in our study is over 65 years and in most studies the statistical association is established by age groups.7,12 However, it is the first work in which this characteristic has been found in terms of age. The explanation for this fact may be similar to the one already given to try to elucidate the differences in the different percentages of hospital-acquired influenza between studies. It should also be noted that our study included two patients with hospital-acquired influenza contracted during the 2009 pandemic, with a mean age of 28.5 years, which could have a significant influence; the other available articles do not include patients admitted during the influenza pandemic.

Although it was not a significant value, influenza vaccination should be taken into account in our work, since vaccination coverage in both groups was very low: 38% in individuals with hospital-acquired influenza and 46.5% in subjects with community-acquired influenza. Both percentages are a long way from the 75% recommended by the World Health Organization for patients with a risk condition15, predominantly among hospitalised patients. These data could indicate that patients hospitalised for influenza are the least vaccinated, although further studies are needed in this regard. On the other hand, Boey et al.16 posit that a possible explanation for the low vaccination coverage rates among patients with risk conditions is that these patients are subject to closer follow-up by specialist doctors and therefore see their primary care doctor less frequently, a setting in which the influenza vaccination is more strongly encouraged. This all reinforces the premise that vaccination campaigns must be bolstered, particularly among vulnerable groups.

In the pathological background analysis, our data are in line with those published by other authors, with an increased frequency of chronic diseases. Characteristically, we show that a history of immunodeficiency behaved as an independent risk factor (aOR=2.31; 95% CI: 1.47–3.60), a common finding in several works.7,8,12 Another item of information shared with the other authors was mean hospital stay, which was longer for hospital-acquired influenza.7,14

On the other hand, in some investigations hospital-acquired influenza was associated with more severe disease12, while in others no differences were found.7 In our study, hospital-acquired influenza was more severe, with a higher frequency of bacterial superinfection, ARDS and ICU admissions. This finding reinforces the need to intervene more decisively in hospital-acquired infection transmission policies by creating packages of standardised measures, continuous training, multidisciplinary involvement and a strict review of compliance.

In terms of mortality, different authors submit important conclusions. Enstone et al.17 found that mortality among patients with hospital-acquired influenza was 26.7% and Álvarez-Lerma et al.18 demonstrated a mortality of 39.2%. Both studies showed markedly higher mortality rates compared to community-acquired influenza, although it is true that the studies were conducted during the 2009 influenza pandemic season. Similarly, in the work by Godoy et al.7, the acquisition of hospital-acquired influenza behaved as an independent risk factor for mortality (aOR=1.86; 95% CI: 1.07–3.23). In our work, this difference was not significant, although the percentage of deaths was higher for hospital-acquired influenza than for community influenza and bordered on statistical significance (17.3 vs. 11.6; p=0.059).

We realise that this research has certain limitations. First of all, it was carried out in a single cohort, therefore the extrapolation of the information to the general population is limited. Secondly, since only the variables recommended by the Community of Madrid's epidemiological surveillance system were collected9, certain data that would have been interesting to analyse were not included in the document. In addition, some data were not available, since the information was obtained retrospectively from medical records. Thirdly, it must be taken into account that when cases of hospital-acquired influenza are compared to severe (hospitalised) cases, it is difficult to observe certain differences, such as the estimation of the vaccine's effectiveness. Finally, morbidity and mortality and long-term evolution were not determined, hence the severity of the disease was probably underestimated.

ConclusionsOur work allows us to conclude that hospital-acquired influenza has a significant impact on hospitalised patients, since their condition is more serious. Our study identified 8.7% of hospital-acquired influenza over 10 seasons, which was more frequent in patients with comorbidities, and more specifically in subjects with immunodeficiencies. In addition, patients with hospital-acquired influenza have an increased risk of contracting bacterial superinfection, of being admitted to the ICU and of developing ARDS. This all allows us to conclude that it is very important to improve the diagnosis of cases of hospital-acquired influenza, since they result in increased morbidity in hospitalised patients as well as in financial costs.

Authors/contributorsDoctors Mangas, Zamarrón, Carpio, Álvarez-Sala, Arribas and Prados contributed to the design and correction of the article, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the variables, drafting, review and approval of the manuscript. The influenza working group of the Hospital Universitario La Paz contributed to the data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results.

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestNone.

The members of the Seasonal Influenza Working Group of the Hospital Universitario La Paz are:

Ríos JJ, Arribas JR, Figueira JC, Díaz-Pollán B, Madero D, Cobas J, Forés G, Baquero F, Pinto MJ, Pastor M, Ramos H, García S, Martins G, Robustillo A, San Juan I y Álvarez-Sala R, Prados C.