This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of dalbavancin as sequential therapy in patients with infective endocarditis (IE) due to gram positive bacteria (GPB) in a real-life heterogenous cohort with comorbid patients.

MethodsA single center retrospective cohort study including all patients with definite IE treated with dalbavancin between January 2017 and February 2022 was developed. A 6-month follow-up was performed. The main outcomes were clinical cure rate, clinical and microbiological relapse, 6-month mortality, and adverse effects (AEs) rate.

ResultsThe study included 61 IE episodes. The median age was 78.5 years (interquartile range [IQR] 63.2–85.2), 78.7% were male, with a median Charlson comorbidity index of 7 (IQR 4–9) points. Overall, 49.2% suffered native valve IE. The most common microorganism was Staphylococcus aureus (26.3%) followed by Enterococcus faecalis (21.3%). The median duration of initial antimicrobial therapy and dalbavancin therapy were 27 (IQR 20–34) and 14 days (IQR 14–28) respectively. The total reduction of hospitalization was 1090 days. The most frequent dosage was 1500mg of dalbavancin every 14 days (96.7%). An AE was detected in 8.2% of patients, only one (1.6%) was attributed to dalbavancin (infusion reaction). Clinical cure was achieved in 86.9% of patients. One patient (1.6%) with Enterococcus faecalis IE suffered relapse. The 6-month mortality was 11.5%, with only one IE-related death (1.6%).

ConclusionThis study shows a high efficacy of dalbavancin in a heterogeneous real-world cohort of IE patients, with an excellent safety profile. Dalbavancin allowed a substantial reduction of in-hospital length of stay.

Evaluar la efectividad de la dalbavancina como tratamiento de consolidación en endocarditis infecciosa (EI) por bacterias grampositivas en una cohorte heterogénea en vida real.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo unicéntrico, incluyendo a los pacientes con EI definitiva tratados con dalbavancina entre enero del 2017 y febrero del 2022. Se realizó un seguimiento de 6 meses. Se evaluaron la tasa de curación clínica, la recaída clínica y microbiológica, la mortalidad a los 6 meses y la tasa de efectos adversos (EA).

ResultadosSe incluyó a 61 episodios de EI. La mediana de edad fue 78,5 años (rango intercuartílico [RI] 63,2-85,2), el 78,7% eran varones, con una mediana del índice de comorbilidad de Charlson de 7 puntos (RI 4-9). El 49,2% presentó EI nativa. El microorganismo más frecuente fue Staphylococcus aureus (26,3%), seguido de Enterococcus faecalis (21,3%). La mediana de duración de antibioterapia inicial y del tratamiento con dalbavancina fueron de 27 (RI 20-34) y 14 días (RI 14-28), respectivamente. La reducción total de la estancia media fue de 1.090 días. La posología más frecuente fue de 1.500mg de dalbavancina cada 14 días (96,7%). Se detectó algún EA en el 8,2% de los pacientes, solo uno (1,6%) se atribuyó a dalbavancina (reacción infusional). Se logró la curación clínica en el 86,9%. Un paciente (1,6%), con EI por Enterococcusfaecalis, presentó recaída. La mortalidad a los 6 meses fue del 11,5%, con una sola muerte relacionada con la EI (1,6%).

ConclusiónNuestro estudio muestra una alta eficacia de dalbavancina en una cohorte heterogénea de pacientes con EI, con un excelente perfil de seguridad, permitiendo una reducción sustancial de la estancia hospitalaria.

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a complex infection with a high mortality rate despite the improvements in diagnosis and treatment in last decades. The standard of care treatment still requires several weeks of parenteral antimicrobial therapy. There are several new strategies which are being implemented in recent years, as sequential oral therapy and outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT).

Long-acting lipoglycopeptides such as dalbavancin may represent another suitable treatment option for IE in the form of outpatient antimicrobial therapy. This antibiotic exhibits some special pharmacokinetic properties, with a uniquely long terminal half-life of 14.4 days.1 This allows to optimize dosing, reducing length of hospital stay and potentially providing economic savings.

Dalbavancin is a semisynthetic lipoglycopeptide derivative of teicoplanin, available intravenously and active against gram positive bacteria (GPB) including Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), and vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA).2 Treatment-emergent adverse effects (AEs) are infrequent (14% in some studies) and usually do not require discontinuation of therapy.3

Dalbavancin use in IE has been described in case reports and retrospective cohort studies.4–13 It seems that dalbavancin might be a useful antibiotic for IE sequential therapy, with a previously described cure rate of about 90% in selected patients.13,14

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of dalbavancin as consolidation therapy in patients with IE due to GPB, in an unselected population reflecting real-life practice, including elder, comorbid patients and complex situations in which surgery was not performed due to high risk.

Material and methodsStudy designThe study was conducted at University Hospital “12 de Octubre” in Madrid, Spain, a tertiary-care university-affiliated hospital with 1250 beds. Our hospital is a referral center for IE surgical management and disposes a multidisciplinary IE team that leads the clinical management of this pathology according to an established local protocol.

A retrospective cohort study was undertaken including adult patients (aged ≥18 years) with IE due to GPB treated with dalbavancin as a sequential consolidation regimen. The institutional central Department of Pharmacy database was searched to identify patients who received intravenous dalbavancin between January 2017 and February 2022 at the hospital. All patients treated with dalbavancin for the indication of definite IE according to the modified Duke criteria were included.15,16 All variables were collected by using a standardized case report form. A 6-month follow-up after completing IE consolidation therapy was performed (in patients receiving chronic suppressive therapy, we performed a 6-month follow-up starting at the end of consolidation phase and beginning of suppressive therapy). The variables and clinical status at the end of follow-up were assessed through a review of electronic health record data. Given the nature of our public health system, it is improbable that a patient would have sought care at another facility in case of relapse or reinfection within the first 6 months after diagnosis. The protocol of our center includes clinical follow-up for all patients and recommendation of blood cultures extraction 1 month after the end of treatment.

This study obtained the approval of the local Research Ethics Committee (reference number 24/148). The study was exempt from requiring a specific informed consent of patients due to its observational retrospective character.

Variables and definitionsCollected data included demographics, chronic underlying conditions, underlying cardiac valvulopathies or prosthetic material implantation, infection-related characteristics, microbiological data, and treatment characteristics. The Charlson comorbidity index was determined at admission.17

Prosthetic IE was considered “early” when it occurred within 12 months post-surgery and “late” when it occurred more than 12 months after surgery.18 As “previous predisposing cardiopathy” we included the presence of significant valve disease (at least mild valvular stenosis or regurgitation) and the presence of prosthetic valve. The intervention date was collected in patients who had surgical valve replacement or implantation of other prosthetic devices. Clinical characteristics including type of valve involvement, and complications at diagnosis and during admission were collected. Complications were defined as any new medical condition developed as a consequence of IE as per the definitions outlined by the ESC Guidelines for the management of IE, and included central nervous system (CNS) embolism, peripheral embolism, new onset valve disease, new onset heart failure, arrhythmias and cardiac blockade, septic metastases and others.15 Complications related to hospitalization and medical or surgical therapy were also collected.

Antimicrobial therapy duration was collected, including total active antimicrobial therapy duration, therapy duration since first negative blood cultures (or since surgery in case of positive intraoperative resection material culture) and dalbavancin therapy duration, as well as posology. Median times of antimicrobial therapy were specifically compared between the first half (2.5 years, from January 2017 to June 2019) of the cohort and the second half (from July 2019 to February 2022). Active antimicrobial treatment required the administration (at the appropriate dosage) of an antimicrobial drug displaying in vitro activity against the isolate, according to EUCAST breakpoints.19 Indication, performance, and type of cardiac surgery for IE were collected. The indication of surgery was considered based on the recommendations of ESC Guidelines for the management of IE.15

Outcomes and definitionsThe main study outcomes were clinical cure rate at the end of the 6-month follow-up, relapse of IE and related mortality. Clinical cure was defined as resolution of symptoms and signs of IE with sterilization of blood cultures and resolution or improvement of cardiac morphological abnormalities in control imaging. IE relapse was defined as a second episode of IE due to the same microorganism within the 6-month follow-up, and IE reinfection was defined as another IE episode during the follow-up caused by a different microorganism from the one identified in the original infection. IE-related mortality was considered when death was attributable to the infectious episode, other nosocomial complication, or to IE complications at any moment of the follow-up, in the absence of an alternative cause.

The secondary outcome was hospitalization-saved time. Hospitalization-saved time was defined as the period in which patients were presumed to receive parenteral antimicrobial therapy as inpatients, according to their clinical characteristics and ESC Guidelines for the management of IE, but instead they were discharged and received outpatient dalbavancin therapy.15

The safety outcomes were AEs rate, development of resistance (during dalbavancin therapy or following its discontinuation) rate, and microbiological failure rate. Microbiological failure was defined as breakthrough bacteremia during dalbavancin therapy, or when the same microorganism was isolated in the blood culture of a patient with IE after completing therapy. AEs occurring during dalbavancin therapy were specifically collected and detailed.

Statistical analysisIn the descriptive analysis, results were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables with non-parametric distribution, and as absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests, as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using the Student's t test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software SPSS (SPSS 23.0, Inc., Chicago, IL).

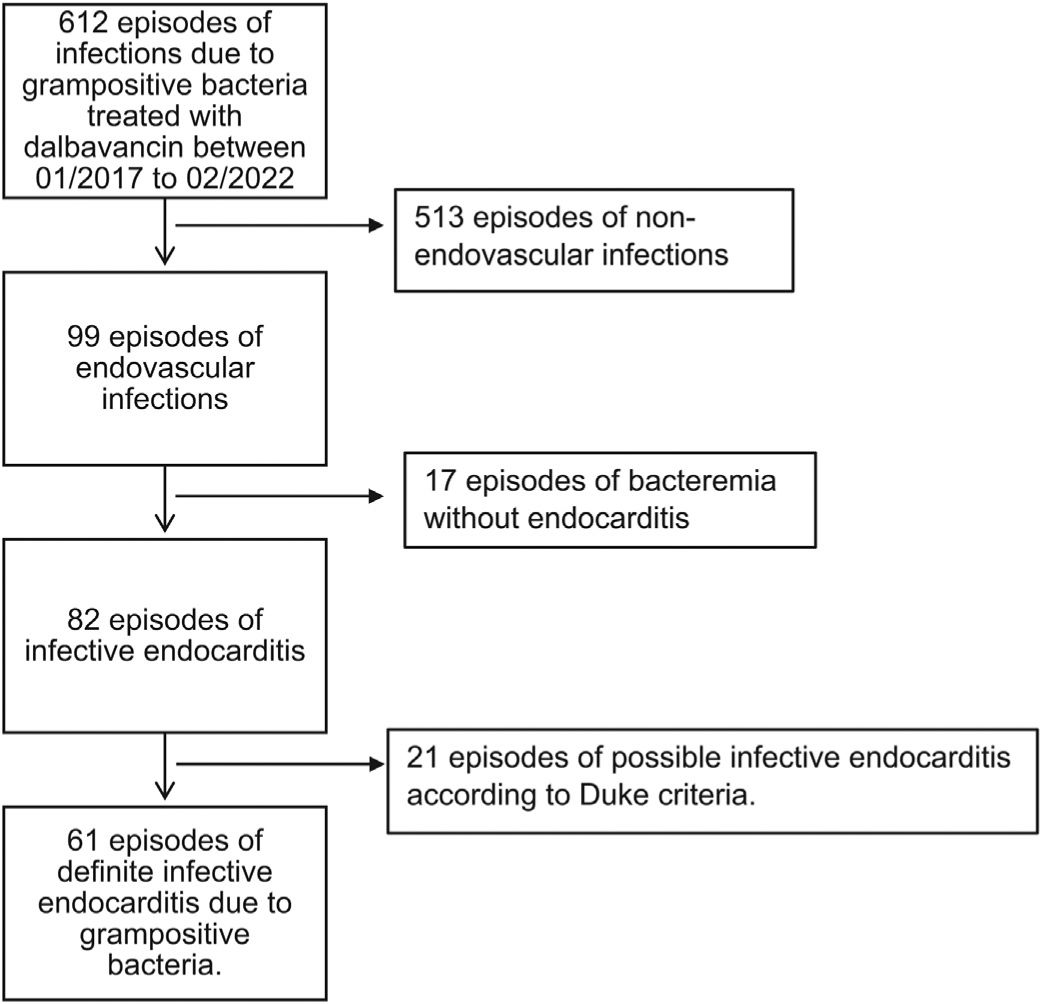

ResultsStudy populationFrom January 2017 to February 2022, 61 episodes of definite IE due to GPB treated with dalbavancin were detected (patient flow chart depicted in Fig. 1).

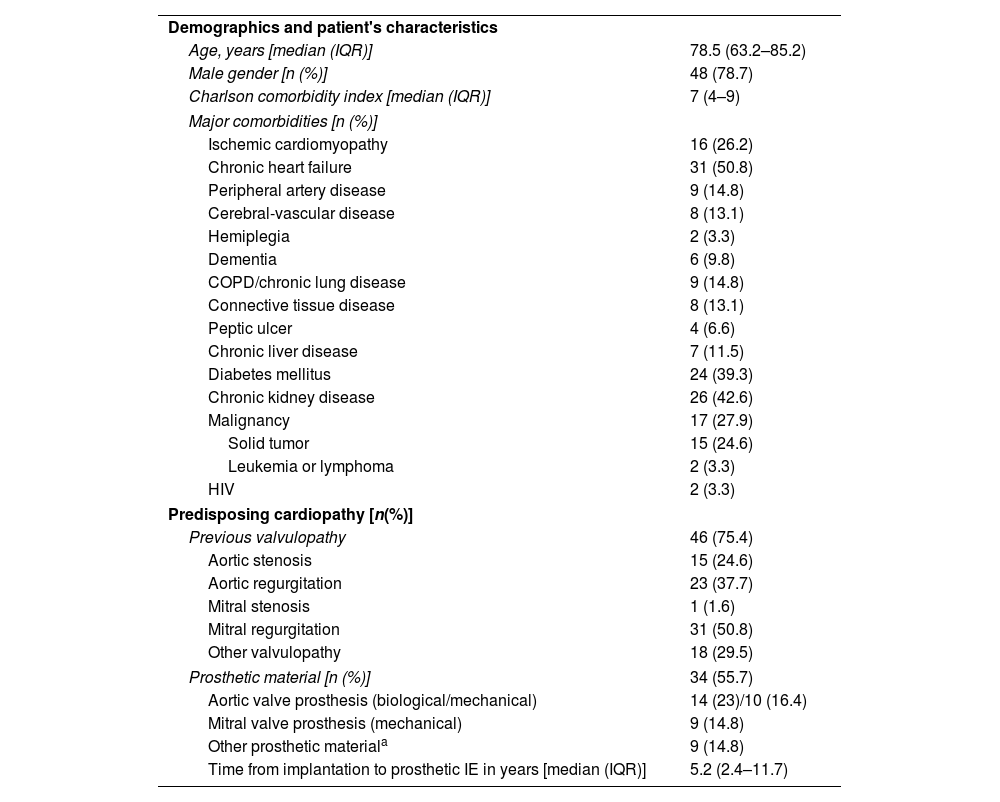

Clinical and demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 78.5 years (interquartile range [IQR] of 63.2–85.2) and 48 (78.7%) patients were male. The median Charlson comorbidity index was 7 (IQR: 4–9) points. The most prevalent predisposing cardiopathy was mitral regurgitation (50.8%), and 55.7% carried prosthetic cardiac devices. In prosthetic or device-associated endocarditis, the median time from implantation to the development of endocarditis was 5.2 years (IQR 2.4–11.7).

Demographics and clinical characteristics of 61 episodes of infective endocarditis due to GPB.

| Demographics and patient's characteristics | |

| Age, years [median (IQR)] | 78.5 (63.2–85.2) |

| Male gender [n (%)] | 48 (78.7) |

| Charlson comorbidity index [median (IQR)] | 7 (4–9) |

| Major comorbidities [n (%)] | |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 16 (26.2) |

| Chronic heart failure | 31 (50.8) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 9 (14.8) |

| Cerebral-vascular disease | 8 (13.1) |

| Hemiplegia | 2 (3.3) |

| Dementia | 6 (9.8) |

| COPD/chronic lung disease | 9 (14.8) |

| Connective tissue disease | 8 (13.1) |

| Peptic ulcer | 4 (6.6) |

| Chronic liver disease | 7 (11.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 24 (39.3) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 26 (42.6) |

| Malignancy | 17 (27.9) |

| Solid tumor | 15 (24.6) |

| Leukemia or lymphoma | 2 (3.3) |

| HIV | 2 (3.3) |

| Predisposing cardiopathy [n(%)] | |

| Previous valvulopathy | 46 (75.4) |

| Aortic stenosis | 15 (24.6) |

| Aortic regurgitation | 23 (37.7) |

| Mitral stenosis | 1 (1.6) |

| Mitral regurgitation | 31 (50.8) |

| Other valvulopathy | 18 (29.5) |

| Prosthetic material [n (%)] | 34 (55.7) |

| Aortic valve prosthesis (biological/mechanical) | 14 (23)/10 (16.4) |

| Mitral valve prosthesis (mechanical) | 9 (14.8) |

| Other prosthetic materiala | 9 (14.8) |

| Time from implantation to prosthetic IE in years [median (IQR)] | 5.2 (2.4–11.7) |

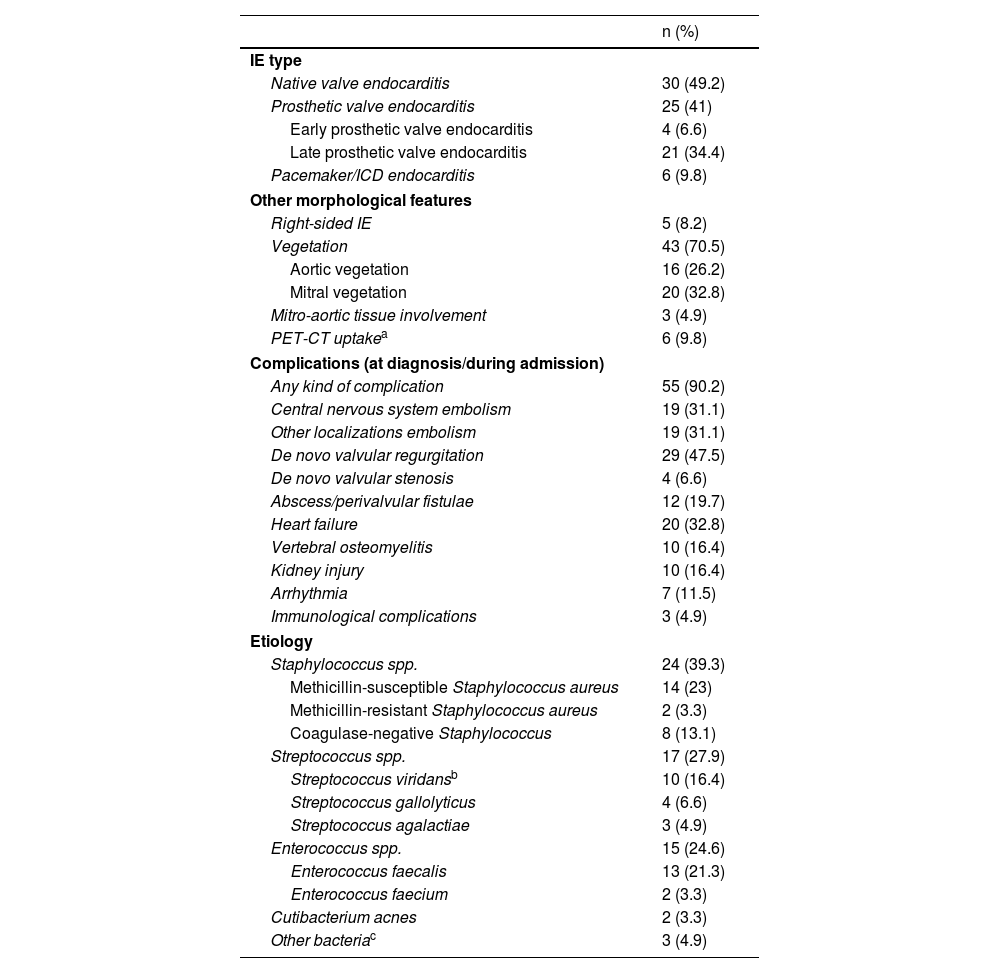

Valve involvement, complications and etiology are shown in Table 2. In terms of valvular disease, 49.2% suffered native valve IE, 40.9% prosthetic valve IE and 9.8% device-related IE. There were 70.5% of patients who presented with vegetations in echocardiography, the rest of them were diagnosed on basis of other criteria. The 9.8% of patients were diagnosed using 18F-fluorodesoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) uptake as morphological criterion.

Valve involvement, complications, and etiology of IE.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| IE type | |

| Native valve endocarditis | 30 (49.2) |

| Prosthetic valve endocarditis | 25 (41) |

| Early prosthetic valve endocarditis | 4 (6.6) |

| Late prosthetic valve endocarditis | 21 (34.4) |

| Pacemaker/ICD endocarditis | 6 (9.8) |

| Other morphological features | |

| Right-sided IE | 5 (8.2) |

| Vegetation | 43 (70.5) |

| Aortic vegetation | 16 (26.2) |

| Mitral vegetation | 20 (32.8) |

| Mitro-aortic tissue involvement | 3 (4.9) |

| PET-CT uptakea | 6 (9.8) |

| Complications (at diagnosis/during admission) | |

| Any kind of complication | 55 (90.2) |

| Central nervous system embolism | 19 (31.1) |

| Other localizations embolism | 19 (31.1) |

| De novo valvular regurgitation | 29 (47.5) |

| De novo valvular stenosis | 4 (6.6) |

| Abscess/perivalvular fistulae | 12 (19.7) |

| Heart failure | 20 (32.8) |

| Vertebral osteomyelitis | 10 (16.4) |

| Kidney injury | 10 (16.4) |

| Arrhythmia | 7 (11.5) |

| Immunological complications | 3 (4.9) |

| Etiology | |

| Staphylococcus spp. | 24 (39.3) |

| Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus | 14 (23) |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 2 (3.3) |

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus | 8 (13.1) |

| Streptococcus spp. | 17 (27.9) |

| Streptococcus viridansb | 10 (16.4) |

| Streptococcus gallolyticus | 4 (6.6) |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 3 (4.9) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 15 (24.6) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 13 (21.3) |

| Enterococcus faecium | 2 (3.3) |

| Cutibacterium acnes | 2 (3.3) |

| Other bacteriac | 3 (4.9) |

Uptake at the valve level in nuclear medicine imaging tests (PET-CT or scintigraphy with labeled leukocytes) as a morphological criterion for IE.

Some sort of complication directly related to IE developed in 90.2% of patients, with 31.1% of CNS embolisms, a 54.1% of de novo valvulopathy and 32.8% de novo heart failure.

The most common etiological bacteria causing IE was Staphylococcus spp. (39.3%), representing S. aureus the 26.3% (23.0% MSSA and 3.3% MRSA). The 27.8% of episodes were caused by Streptococcus spp., and the 24.6% by Enterococcus spp.

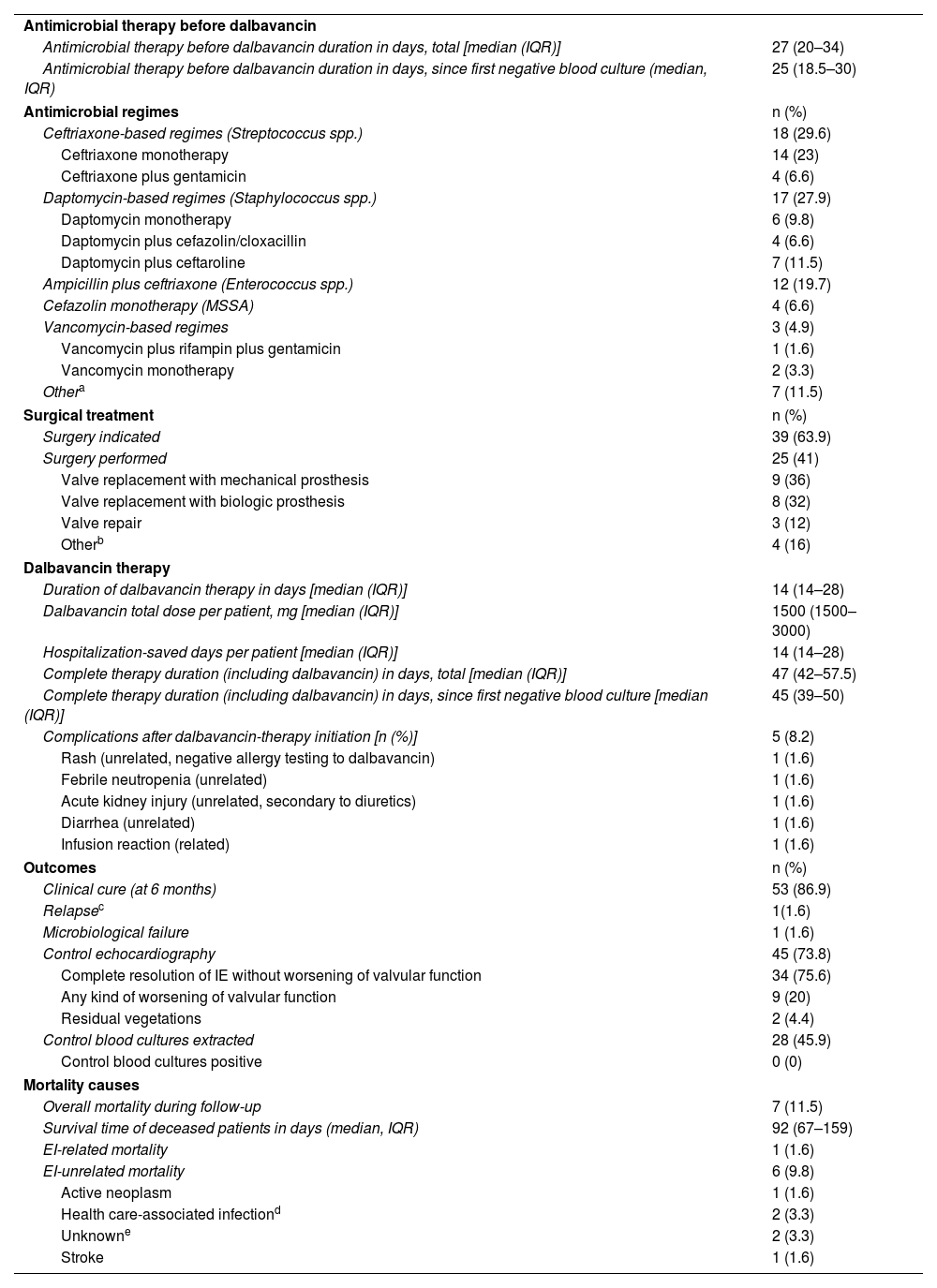

Antimicrobial therapy and surgeryFeatures of antimicrobial therapy, surgery and outcomes are shown in Table 3. The median duration of antimicrobial therapy (before receiving dalbavancin) since the beginning of an active antibiotic was 27 days (IQR 20–34). The initial antimicrobial regimes were adjusted by the IE team according to the type of bacteria isolated and the local protocol, the most common were ceftriaxone-based regimes (29.6%, for streptococcal IE), daptomycin-based regimes (27.9%, for staphylococcal IE) and ampicillin plus ceftriaxone (19.7%, for enterococcal IE).

Therapy and outcomes [n (%)].

| Antimicrobial therapy before dalbavancin | |

| Antimicrobial therapy before dalbavancin duration in days, total [median (IQR)] | 27 (20–34) |

| Antimicrobial therapy before dalbavancin duration in days, since first negative blood culture (median, IQR) | 25 (18.5–30) |

| Antimicrobial regimes | n (%) |

| Ceftriaxone-based regimes (Streptococcus spp.) | 18 (29.6) |

| Ceftriaxone monotherapy | 14 (23) |

| Ceftriaxone plus gentamicin | 4 (6.6) |

| Daptomycin-based regimes (Staphylococcus spp.) | 17 (27.9) |

| Daptomycin monotherapy | 6 (9.8) |

| Daptomycin plus cefazolin/cloxacillin | 4 (6.6) |

| Daptomycin plus ceftaroline | 7 (11.5) |

| Ampicillin plus ceftriaxone (Enterococcus spp.) | 12 (19.7) |

| Cefazolin monotherapy (MSSA) | 4 (6.6) |

| Vancomycin-based regimes | 3 (4.9) |

| Vancomycin plus rifampin plus gentamicin | 1 (1.6) |

| Vancomycin monotherapy | 2 (3.3) |

| Othera | 7 (11.5) |

| Surgical treatment | n (%) |

| Surgery indicated | 39 (63.9) |

| Surgery performed | 25 (41) |

| Valve replacement with mechanical prosthesis | 9 (36) |

| Valve replacement with biologic prosthesis | 8 (32) |

| Valve repair | 3 (12) |

| Otherb | 4 (16) |

| Dalbavancin therapy | |

| Duration of dalbavancin therapy in days [median (IQR)] | 14 (14–28) |

| Dalbavancin total dose per patient, mg [median (IQR)] | 1500 (1500–3000) |

| Hospitalization-saved days per patient [median (IQR)] | 14 (14–28) |

| Complete therapy duration (including dalbavancin) in days, total [median (IQR)] | 47 (42–57.5) |

| Complete therapy duration (including dalbavancin) in days, since first negative blood culture [median (IQR)] | 45 (39–50) |

| Complications after dalbavancin-therapy initiation [n (%)] | 5 (8.2) |

| Rash (unrelated, negative allergy testing to dalbavancin) | 1 (1.6) |

| Febrile neutropenia (unrelated) | 1 (1.6) |

| Acute kidney injury (unrelated, secondary to diuretics) | 1 (1.6) |

| Diarrhea (unrelated) | 1 (1.6) |

| Infusion reaction (related) | 1 (1.6) |

| Outcomes | n (%) |

| Clinical cure (at 6 months) | 53 (86.9) |

| Relapsec | 1(1.6) |

| Microbiological failure | 1 (1.6) |

| Control echocardiography | 45 (73.8) |

| Complete resolution of IE without worsening of valvular function | 34 (75.6) |

| Any kind of worsening of valvular function | 9 (20) |

| Residual vegetations | 2 (4.4) |

| Control blood cultures extracted | 28 (45.9) |

| Control blood cultures positive | 0 (0) |

| Mortality causes | |

| Overall mortality during follow-up | 7 (11.5) |

| Survival time of deceased patients in days (median, IQR) | 92 (67–159) |

| EI-related mortality | 1 (1.6) |

| EI-unrelated mortality | 6 (9.8) |

| Active neoplasm | 1 (1.6) |

| Health care-associated infectiond | 2 (3.3) |

| Unknowne | 2 (3.3) |

| Stroke | 1 (1.6) |

Other therapies (including different combinations of the previous antibiotics, sometimes influenced by beta-lactams allergy or clinical suspicion of other infectious source): moxifloxacin plus tedizolid (one patient, Staphylococcus hominis), piperacillin/tazobactam (one patient, Lactococcus garviae), ampicillin plus daptomycin (one patient, Enterococcus faecium), ceftriaxone plus daptomycin (one patient, Streptococcus viridans), daptomycin plus gentamicin (one patient, C. acnes), ampicillin monotherapy (one patient, Listeria monocytogenes), cefazolin plus rifampin (one patient, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus epidermidis).

Surgery was indicated in 63.9% of patients, 41% of them finally underwent intervention (64.1% of patients who had indication). The main reason for not performing surgery was high surgical risk due to comorbidity and frailty of the patient (85.7%), the remaining cases were due to patient rejection.

Dalbavancin therapyThe median duration of dalbavancin therapy was 14 days (IQR 14–28, range 14–215 days). Dosage was 1500mg each 14 days in 96.7% of patients, one patient (1.6%) received 1000mg on day 0 and 500mg on day 7, and other patient (1.6%) received 1500mg on day 0 and 7.

There were three patients with a dalbavancin therapy duration superior to 12 weeks, with specific situations in which microbiological cure was considered troublesome. One of them suffered a Cutibacterium acnes IE, with implant of a new prosthesis before clinical cure. The second patient had persistent 18F-FDG PET-CT uptake in a prosthetic valve. The third patient suffered a prosthetic IE with a large abscess and was not eligible for surgery.

One patient (1.6%) received a concomitant antibiotic therapy alongside dalbavancin, specifically oral amoxicillin, during an episode of IE caused by C. acnes.

The 8.2% of patients developed some kind of AE after administration of dalbavancin, even though only one patient (1.6%) suffered dalbavancin-related toxicity (infusion reaction). The remaining AEs were attributable to other etiologies: chronic diarrhea worsening in a patient with short-bowel syndrome (during therapy with simultaneously administered oral amoxicillin), unspecific rash with negative allergy test for dalbavancin, neutropenia (attributed to active neoplasia treatment and cotrimoxazole), and acute kidney injury due to diuretics and sacubitril–valsartan therapy.

OutcomesThe median hospitalization-saved time was 14 days (IQR 14–28), and the total hospitalization-saved estimated time was 1090 days for the whole cohort. The median duration of complete antimicrobial therapy including dalbavancin was 47 days (IQR 42–57.5).

Comparing the first half period of inclusion of the cohort with the second half, we did not find significant differences between the median total antimicrobial therapy time (43.5 vs 48 days, p=0.84), median antimicrobial therapy time prior to dalbavancin (25 vs 25 days, p=0.64) or median dalbavancin therapy time (14 vs 14 days, p=0.84). Individual episodes detailed therapy duration are available in Table S2 (supplementary appendix).

Clinical cure at the end of the 6-month follow-up was achieved in 86.9% of patients. Only one patient (1.6%) suffered IE relapse during follow-up. Therapy failure, in this case, was attributed to inadequate source control (prosthetic valve IE caused by E. faecalis with initial rejection of surgery due to high risk, performing conservative therapy). After relapse (84 days after stopping dalbavancin therapy), surgery was performed. Persistent 18F-FDG uptake on PET-CT valve imaging was observed, deciding to maintain prolonged dalbavancin therapy after surgery.

There was no evidence of resistance development to dalbavancin or lipoglycopeptides in any case. Dalbavancin susceptibility was not routinely tested (it was extrapolated from vancomycin/teicoplanin susceptibility), except in the episode of relapse, in which susceptibility to dalbavancin was tested and confirmed.

Control blood cultures were obtained in 45.9% of patients a month after antimicrobial therapy cessation, with none of them resulting positive.

Control transthoracic echocardiography was performed in 73.8% of patients after therapy cessation, in 3.2% residual vegetations were observed, nevertheless all of them were considered as having favorable evolution. In 20% of the cases, a worsening of valvular function was detected, and in the remaining 76.8% complete resolution of IE without worsening of valvular function was observed. In two of the patients diagnosed using 18F-FDG uptake on PET-CT as morphologic criterion (33%), a control PET-CT was performed after finishing antimicrobial therapy, both studies were negative for IE therefore ensuring clinical cure.

Overall, seven patients (11.5%) died during follow-up, only one (14.3% of those who died, 1.6% of the cohort) as a direct unfavorable outcome of IE. The rest of them perished due to unrelated events: two of them (28.5%) due to non-related infections (pulmonary aspergillosis and urinary sepsis), one (14.3%) due to metastatic cancer, and another one (14.3%) due to ischemic stroke (attributed to atrial fibrillation without anticoagulant therapy, without evidence of relapse of IE). The other two patients (28.6%) died of unknown causes (without data in medical registry), even though both were elder comorbid patients who were institutionalized in nursing homes (one of them with an active malignancy).

There were no statistically significant differences in clinical variables and outcomes between etiologies (Table S1 (supplementary appendix)).

DiscussionDalbavancin is a promising alternative as a consolidation therapy in IE patients as shown in previous studies.4–13 Our study contributes to the current literature of IE treatment with dalbavancin with a real-life experience of a cohort involving older patients with heterogeneous clinical features and different characteristics than the highly selected populations of the previous reports.

Our study population has certain differences when compared with previous studies. Our population is conspicuously older (median age of 78.5 years in our cohort vs 48 years in previous studies), more comorbid, and experience a higher frequency of prosthetic valve IE (40.9% in our cohort vs 27% in previous studies).14 There is also a higher rate of enterococcal IE in our cohort, according to the change of etiology trend in recent times. We also observe a low rate of MRSA IE in our cohort, higher rates of coagulase-negative staphylococci, and two episodes of C. acnes infection. We consider this important to report, given that C. acnes IE is infrequent and there is not previous published experience of dalbavancin therapy in this situation.20,21 Our most frequent dosage (1500mg each two weeks) is also different than what has been reported in previous studies (1000mg initially and then 500mg weekly), supporting the utility and safety of that dosage.

The efficacy of treatment was very high and consistent within different types of IE (native, prosthetic and device-associated) and etiologies, with a clinical cure rate of 86.9%. There was only one relapse and one decease attributable to IE (3.3% of the cohort), while the other 9.8% of patients died due to unrelated events. This data suggests that dalbavancin is an effective therapy that may replace the current long intravenous standard of care therapies, being specially useful in complex situations (prosthetic material not surgically removed, enterococcal infection) in which consolidation therapy may need to be prolonged.

The only relapse was attributable to the impossibility of source control in an enterococcal prosthetic valve IE with criteria for surgery but rejection of intervention. The only IE-related death was due to multiple complications in a patient who suffered native mitral IE caused by Staphyloccoccus epidermidis, developing later catheter-related candidemia and finally perishing of respiratory failure without discarding a negative outcome of IE despite the absence of breakthrough bacteremia. This episode was classified as death related to IE in an attempt of reporting any possible treatment failure, but it is not clear that it was related to an unfavorable outcome of the initial infection.

In addition, our study shows an excellent security profile for dalbavancin treatment, with only one relevant AE (infusion reaction), even though the retrospective design of the study might have underestimated the rate of AEs.

Our study also assesses the economic impact with an important reduction of the in-hospital length of stay, allowing patients to complete therapy as outpatients and therefore providing economic savings as previous studies have shown.12 Comparing with other alternatives to traditional hospitalization which also reduce economic costs, dalbavancin therapy avoids the possible non-adherence to oral therapy, and avoids the complications associated with lines and multiple doses of antimicrobial therapy required in OPAT. In this context, dalbavancin seems like an excellent alternative to consolidate therapy securing adherence and avoiding hospital-care complications.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations for this study that must be highlighted. Firstly, our study design is retrospective without pre-specified selection criteria, notwithstanding it represents a real-life experience. Randomized clinical trials are needed to establish the most effective approach as a sequential therapy.

Secondly, our study population consists of a selected cohort of patients who were already showing favorable progress at the time of therapy switch. However, once patients achieved clinical stability, dalbavancin was administered as the standard consolidation therapy in the majority of cases at our center. Additionally, our population comprises a high proportion of elderly and comorbid patients who did not undergo surgery, a factor that may have adversely influenced outcomes.

Thirdly, another issue in our study is a median duration of therapy longer than expected. Our median antibiotic therapy duration before dalbavancin administration was 27 days, whereas the median time in previous studies was three weeks.14 Several factors may be implicated in this finding. The bad clinical situation in the initial weeks of therapy and the frailty of patients are likely related to this issue. In our cohort there is a not negligible proportion of patients with an individualized longer duration of treatment due to persistent findings in echocardiography or PET-CT or due to the impossibility of undergoing surgery. Dalbavancin might also be the preferred choice in the selected patients in which a longer than usual therapy duration is planned because of special conditions as the presence of prosthetic material which cannot be removed due to high risk or comorbidities. Owing to the concern of a possible delay in therapy switch (from other therapies to dalbavancin) during the initial years of the cohort, we compared the first half with the second one without finding any difference. Previous studies (with a shorter median time of initial treatment) have shown that an earlier switch to dalbavancin, once the patient is clinically stable, is feasible and safe. The individual needs of antibiotic therapy duration in relation to the clinical features of each case are described in Table S2 (supplementary appendix).

Lastly, a relatively low proportion of control blood cultures were extracted after the end of therapy. This could have underestimated relapses. However, in the clinical prospective follow-up, not any additional relapse was detected.

In conclusion, dalbavancin is a safe alternative as a sequential therapy in IE patients, showing an excellent cure rate without AEs, and allowing early discharge from hospital.

Conflicts of interestE.A. received financial support for education purposes from Angelini Pharma España, S.L.U. The rest of authors did not have any financial or non-financial interests to disclose.