Surgery is the only curative treatment for primary hyperparathyroidism (PHP).1 In the hands of an expert surgeon, peroperative bilateral cervical examination achieves curing rates of 86–100% without the need for preoperative localization tests. Localization tests are, however, essential in the event of minimally invasive surgery or repeat surgery for disease relapse/recurrence.1 Thanks to technological advances and the high resolution of current imaging tests, most pathological parathyroid glands may easily be identified using noninvasive procedures. However, these sometimes provide non-significant or conflicting results. When this occurs, invasive procedures such as parathyroid catheterization are required.

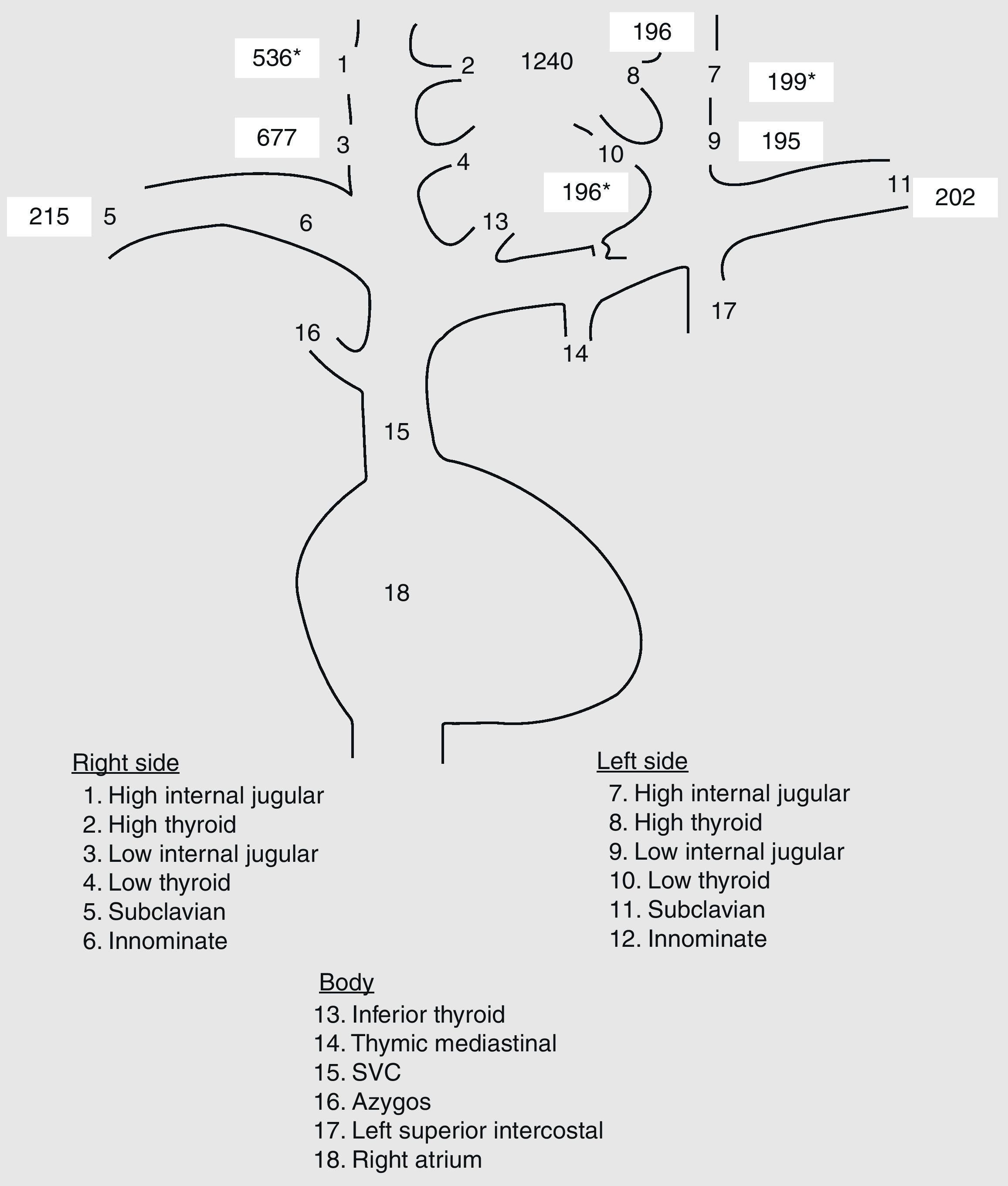

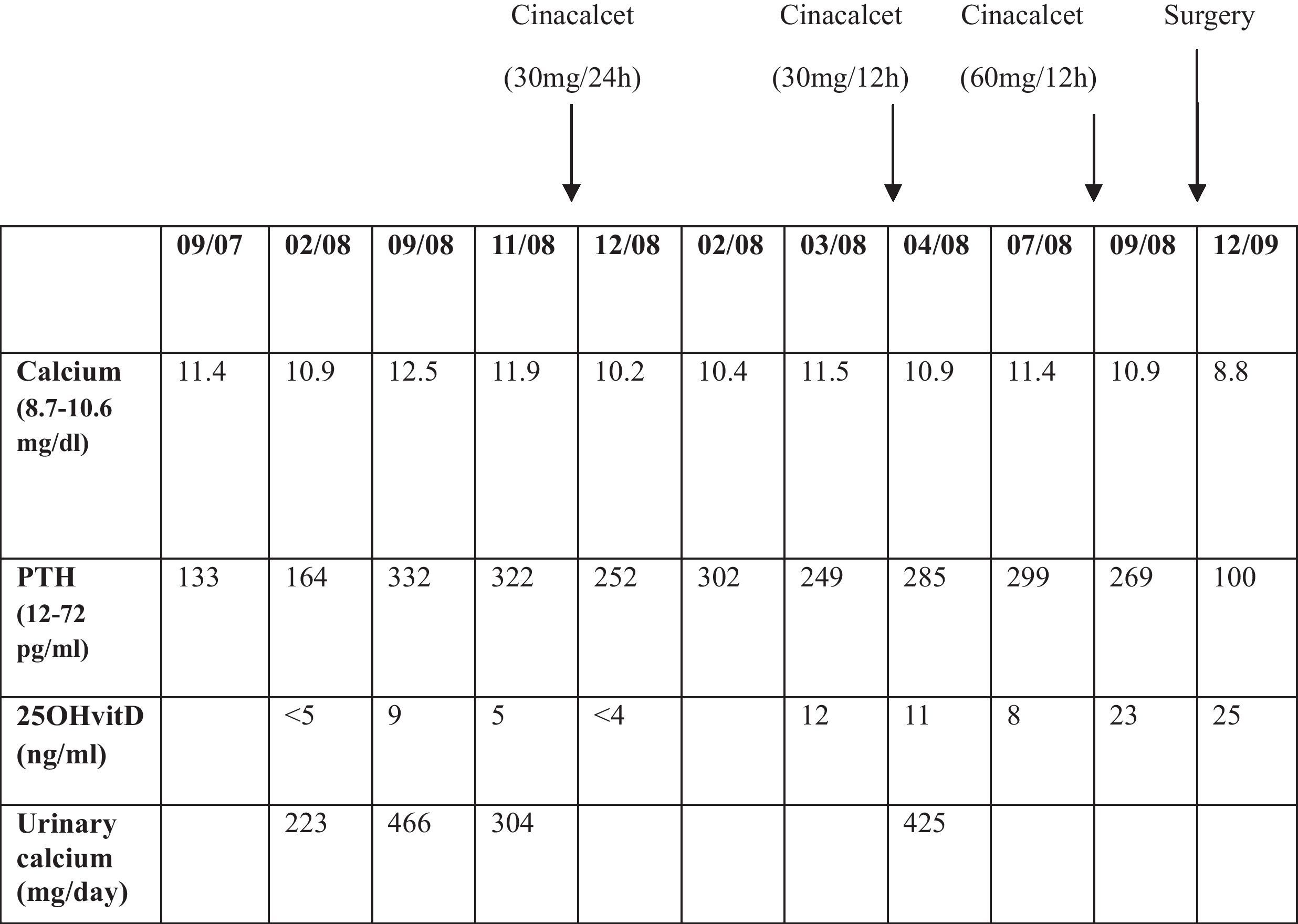

We report the case of a 65-year-old female patient with a history of multinodular goiter and PHP due to parathyroid adenoma who had undergone total thyroidectomy and right superior parathyroidectomy. The adenoma could not be localized with standard imaging tests (cervical ultrasound, technetium-sestamibi scan, and cervical magnetic resonance imaging) performed before surgery, so a bilateral exploratory cervicotomy was performed. A 1.5cm parathyroid adenoma was found adhering to the posterosuperior aspect of the right thyroid lobe and resected. All the other parathyroid glands identified (left upper, left lower, and right lower glands) were normal. The patient is currently on thyroxine therapy (100mcg/day). One year after surgery, asymptomatic hypercalcemia and high parathormone (PTH) levels were again found 1 year after surgery (Table 1). Laboratory tests also showed severe hypovitaminosis D, and treatment was therefore started with calcidiol despite hypercalcemia (4drops/day). All other laboratory test results were normal. Based on a suspicion of PHP relapse as the first diagnostic possibility, perhaps due to a prior partial adenoma resection or the presence of a double adenoma, localization studies were requested. Two parathyroid technetium-sestamibi scans showed no pathological deposits. A cervical ultrasound showed no suspicious images either. Finally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck showed no relevant findings. During this time, and despite strong hydration, plasma and urinary calcium and PTH levels continued to increase. For this reason, and based on a diagnosis of PHP relapse with negative localization tests, treatment was started with low-dose cinacalcet (30mg/day) and surgical assessment was requested. Plasma calcium levels normalized one month after the start of the calciomimetic drug. Surgery was therefore rejected because of the difficulties and risks of “blind” repeat surgery in a previously operated area. Plasma calcium levels increased again four months later, and the cinacalcet dose was increased to 30mg/12h, which normalized calcium levels. Four months later, calcemia increased again, and the cinacalcet dose was increased to 60mg/12h. At this point, and because of poor drug tolerability (nausea and epigastric pain) and poor calcemia control, surgery was decided upon as the only possible definitive treatment. In order to minimize risks and facilitate surgical success, parathyroid catheterization was performed before surgery. For this, the thyroid-parathyroid veins were catheterized and PTH samples were taken (Fig. 1). The right lower thyroid vein could not be catheterized due to technical difficulties and anatomical variants. Despite this, catheterization showed a clear right lateralization. During surgery, a 1.3cm adenoma was again found in the right superior parathyroid gland and resected. Fifteen minutes after resection, PTH levels decreased by 80% (initial PTH, 239pg/mL; final PTH, 51pg/mL). Calcemia also normalized after surgery (8.8mg/dL), and cinacalcet was therefore discontinued. One year later, calcium and PTH levels continue to be normal.

The need for the localization of pathological parathyroid glands before initial surgery for PHP is controversial. This is because while their identification allows for minimally invasive surgery (with less costs and complications), conventional surgery with peroperative bilateral cervical examination still has success rates >95% with morbidity rates of only 1–2%.2

However, PHP persists or recurs in 5–10%3 of cases, requiring repeat surgery. This is technically more complex due to postoperative fibrosis and anatomical distortion and involves higher costs4 and risks of complications2 such as recurrent nerve paralysis, permanent hypoparathyroidism, local bleeding, pseudoaneurysm, thrombosis, or infection. Moreover, one-third of patients undergoing repeat surgery have hyperplasia in several parathyroid glands or ectopic adenomas.3

For these reasons, there is general agreement that adequate localization is mandatory in patients with familial PHP or undergoing repeat surgery. Localization is not possible in most cases using noninvasive procedures, having a predictive value of 40–80%.3 A technetium-sestamibi scan is the procedure with the greatest sensitivity (91%) and specificity (98%), mainly when combined with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).3 Ultrasonography is another commonly used technique, mainly as a supplementary procedure in patients with a negative scan or as a confirmatory test. It has an intermediate sensitivity for adenoma detection (77–80%).3 Finally, computed tomography (CT) or MRI is used in selected cases; these are of particular value in ectopic mediastinal adenomas.3 There is currently no agreement as to how many or which tests should be performed.5 Although results vary depending on the center, it appears that the combination of MRI and a scan would be the one with the highest sensitivity (94%).5

However, all of these procedures have limitations in the event of small adenomas, multiple hyperplasia, or coexistent thyroid disease,2 and their sensitivity markedly decreases in patients undergoing prior surgery.3 In such cases, invasive procedures such as parathyroid catheterization are helpful. For this, bilateral femoral catheterization is used to take PTH samples from the superior/inferior internal jugular, superior/inferior thyroid, subclavian and brachiocephalic, thymic-mediastinal, superior cava, azygos, and left superior intercostal veins and from the right atrium.2 The thymic-mediastinal vein is the vein most difficult to catheterize, but this is essential for localizing mediastinal PHP and thus for deciding on the surgical approach.2 A positive gradient is defined as a twofold greater PTH concentration at the central (right or left) as compared to the peripheral level.2 Peripheral levels are calculated using the mean of measurements in both subclavian veins. Although this is an invasive, expensive, and cumbersome procedure, it has a high chance of success. The largest series was published by the National Institutes of Health6 and reported parathyroid catheterization in 98 patients with persistent/recurrent PHP and two or more negative, discordant, or equivocal localization tests. Parathyroid catheterization showed a true positive rate of 76% and a false positive rate of 4%, and was the most sensitive and specific procedure. These results were supported by Jones et al.,7 who reported sensitivity and specificity rates of 76% and 88%, respectively. Ogilvie et al.1 found in 27 patients with complicated PHP a positive predictive value of 81%, similar to prior studies6,7 and higher than reported for all other noninvasive procedures. Parathyroid catheterization is therefore indicated in the following conditions1,2: (1) discordant/inconclusive imaging tests; (2) more than one scintigraphic uptake area, suggesting the presence of pluriglandular disease or ectopic adenomas; (3) patients with familial PHP; and/or (4) patients with prior neck surgery, as occurred in our case. In addition, in order to perform routine catheterization and decrease its invasiveness/complications, rapid PTH measurements may be performed during catheterization8 or both internal jugular veins may be catheterized with rapid PTH measurement during surgery9 with good and promising results. In the latter case, lateralization is considered to exist in the event of differences >5% in PTH levels.

In conclusion, parathyroid catheterization (before or during surgery) performed at specialized centers is a valuable, sensitive, and specific technique for patients with complicated PHP and one which increases the chance of surgical success.

Please, cite this article as: Prieto Tenreiro AM, et al. Utilidad del cateterismo de paratiroides en la localización de un adenoma de paratiroides recidivante oculto. Endocrinol Nutr. 2012; 59:69–83.