Endocrine tumors are a very heterogeneous group of neoplasms. Mainly neuroendocrine tumors may occur grouped into hereditary tumor syndromes which are transmitted as autosomal dominant disorders. The following syndromes are well characterized, and the genetic changes responsible for their occurrence are known: MEN-1, MEN-2, von Hippel–Lindau syndrome, neurofibromatosis type 1, tuberous sclerosis, Carney's complex, hyperparathyroidism and jaw tumor syndrome, and hereditary paraganglioma–pheochromocytoma syndrome.1

We report the case of a female patient with several endocrine gland tumors who could a priori be considered as a special case of endocrine tumor syndrome.

This was a 65-year-old woman referred to the endocrinology department of Jaén Hospital due to suspected primary hyperparathyroidism and postmenopausal hirsutism. Her family history included type 2 diabetes in the mother and two hypertensive brothers. Her personal history included HBP, vitiligo, renal colics, and menopause at 51 years of age. She reported increased facial hair and hypertrichosis in the limbs, frontoparietal hair loss and increased libido for the previous three years. There was no evidence of thyroid dysfunction or changes in the neck.

Physical examination findings included: weight 78kg, BMI 32kg/m2, blood pressure 120/70mmHg, androgenetic alopecia, and grade 3 hirsutism on the Ferriman–Gallwey scale2 with very marked hypertrichosis in the limbs.

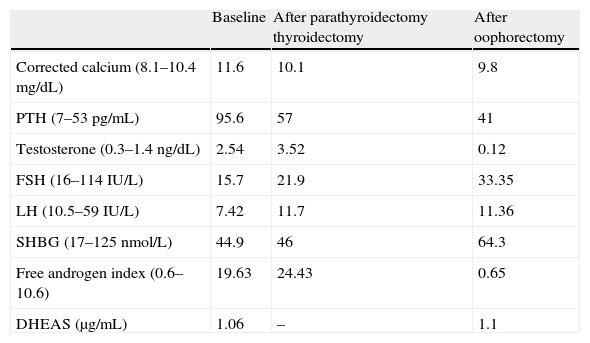

Laboratory tests revealed hypercalcemia with elevated PTH, as well as testosterone above the normal range, with no other pathological data (Table 1). Scintigraphy with Tc-99m sestamibi showed a pathological deposit in the right superior parathyroid gland. Thyroid ultrasonography showed a 2.4cm×2cm×1.5cm nodule in the isthmus with benign characteristics. Finally, transvaginal ultrasonography and a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis were performed with no pathological findings.

Laboratory data before and after surgical procedures (thyroidectomy and oophorectomy).

| Baseline | After parathyroidectomy thyroidectomy | After oophorectomy | |

| Corrected calcium (8.1–10.4mg/dL) | 11.6 | 10.1 | 9.8 |

| PTH (7–53pg/mL) | 95.6 | 57 | 41 |

| Testosterone (0.3–1.4ng/dL) | 2.54 | 3.52 | 0.12 |

| FSH (16–114IU/L) | 15.7 | 21.9 | 33.35 |

| LH (10.5–59IU/L) | 7.42 | 11.7 | 11.36 |

| SHBG (17–125nmol/L) | 44.9 | 46 | 64.3 |

| Free androgen index (0.6–10.6) | 19.63 | 24.43 | 0.65 |

| DHEAS (μg/mL) | 1.06 | – | 1.1 |

Primary hyperparathyroidism was diagnosed, and parathyroidectomy was indicated. During surgery, a thyroid nodule suspicious for malignancy was detected. Intraoperative biopsy suggested a papillary thyroid carcinoma, and total thyroidectomy was therefore performed. After surgery, the patient received ablation therapy with 131I.

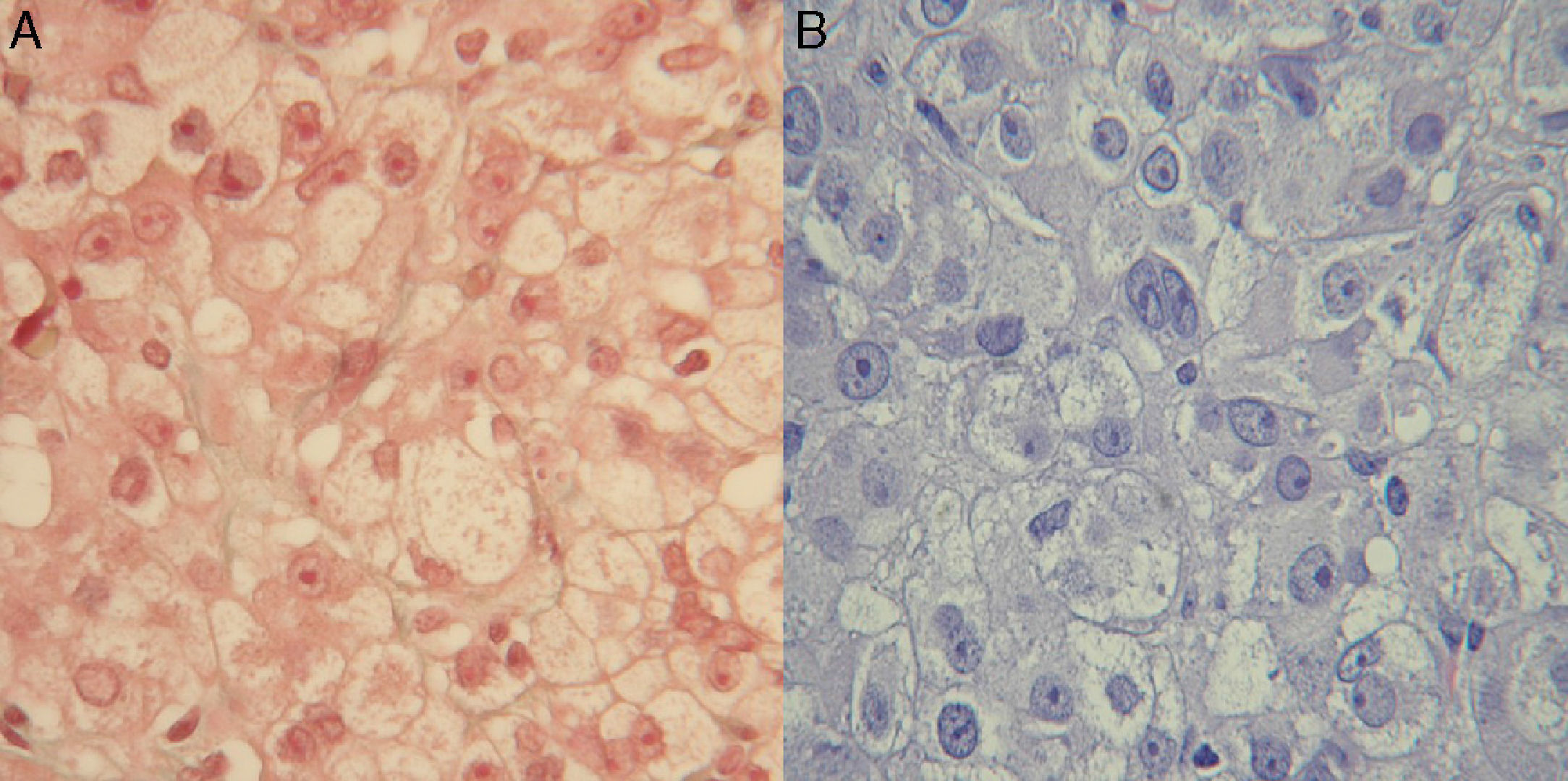

Clinical signs of hyperandrogenism persisted, and even worsened, at subsequent visits. An ovarian origin was suspected and, since imaging tests had been negative, the patient was referred to gynecology for exploratory laparoscopy. Bilateral oophorectomy was performed, and a histological diagnosis was made of steroid cell tumor in the right ovary and hyperthecosis and follicular cysts in the left ovary (Fig. 1).

After oophorectomy, a clear improvement was seen in hyperandrogenism, together with partial hair recovery and decreased hirsutism. Hormone tests performed three months later showed a normalization of the biochemical and hormonal parameters (Table 1).

Two years after oophorectomy, the patient was again referred to endocrinology for clinical signs of diabetes and gradual weight loss (10kg in four months), with a blood glucose level of 342mg/dL associated with glycosuria and ketonuria. Insulin therapy was therefore started at her health care center. Tests performed showed an HbA1c level of 12.1%, negative GAD and IA2 antibodies, and a C-peptide level of 1.4ng/dL.

Metabolic control and clinical condition improved after a short period, and the insulin dose was gradually decreased until it was finally discontinued after one year. The patient currently receives oral antidiabetic drugs with an excellent metabolic control (last HbA1c value, 6.2%). Although LADA diabetes was initially considered because of the clinical severity of hyperglycemia, the subsequent course and family history suggested a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

This patient was finally diagnosed with primary hyperparathyroidism (PHP), papillary thyroid carcinoma, ovarian steroid cell tumor, and diabetes mellitus. These conditions may occur sporadically, but the simultaneous occurrence of all of them outside the clinical context of some of the endocrine tumor syndromes reported to date is striking.

The association of PHP with medullary thyroid cancer in MEN I and IIA syndromes and with differentiated thyroid cancer outside these syndromes is known. Several cases have been reported in which papillary thyroid carcinoma was found during surgery for PHP. The incidence of PHP combined with thyroid cancer has been estimated at 2–13%3. Controversy still exists as to whether both conditions are diagnosed at the same time or are caused by common risk factors and/or genetic changes. Mutation in a proto-oncogen responsible for the simultaneous occurrence of papillary and medullary thyroid carcinoma together with PHP has been reported.4 It is therefore recommended that, in the presence of PHP, neck ultrasonography should be performed to rule out thyroid nodules requiring investigation for suspected non-medullary thyroid carcinoma.

Our patient had concomitant hyperandrogenism, which based on her obesity and history of PHP could have been related to insulin resistance syndrome, which is present in both conditions.5,6 On the other hand, gonadotropin-secreting pituitary tumors have been reported in association with MEN I, which may cause ovarian hyperstimulation.7,8 In our case, however, the finding of abnormally low gonadotropin levels for age and the postmenopausal state of the patient suggested ovarian disease.

The resected ovarian tumor, called steroid cell tumor, Grawitz tumor or corticoadrenaloma, shows adrenal cortex remnants on histological examination.9 The tumor typically occurs in adult females, especially after menopause. In 70–80% of cases, the tumor has androgenic activity and has virilizing effects. A small proportion of these tumors may secrete estrogens, and hypercorticism, including the occurrence of diabetes, has been reported,10 although in our patient this occurred two years after oophorectomy.

The question is to what extent these conditions are mutually independent and are associated by chance, or whether there is some as yet unidentified factor responsible for some predisposition to the development of this type of endocrine disease.

Please cite this article as: Moreno Martínez MM, Sánchez Malo C, Gutiérrez Alcántara C, Montes Castillo C, Santiago Fernández P. Diabetes, tumor ovárico, hiperparatiroidismo y cáncer papilar: ¿una asociación casual? Endocrinol Nutr. 2014;61:548–550.