Secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) by extrapituitary tumors was reported by Liddle in 1962. ACTH secretion occurs in 0.1 cases by million inhabitants in every year, and causes endogenous Cushing syndrome in 10% of cases.1,2 According to the largest series recently reported,1,3–5 bronchial carcinoid is the most common cause of ectopic ACTH secretion (29.4%), followed by small cell lung cancer (11%), medullary thyroid cancer (6.8%), and thymic carcinoid (5.4%). The responsible tumor cannot be found in 19% of cases. Noninvasive functional tests are sometimes unable to differentiate between eutopic and ectopic ACTH secretions, and inferior petrosal sinus sampling should be performed to assess the source of hormone secretion. A case of ectopic ACTH secretion where inadequate interpretation of the results of IPSS resulted in a wrong therapeutic approach is reported below.

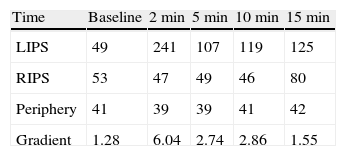

A 38-year-old male with a two-year history of high blood pressure, well controlled with enalapril, first was examined at our center in November 2010. Approximately two years before, because of a chickenpox infection, a computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, showing evidence of severe osteoporosis, which was subsequently confirmed by bone densitometry. High urinary free cortisol (UFC) levels were found at the rheumatology clinic, and the patient was referred to endocrinology for work-up. Patient reported abdominal fat accumulation, red wine-colored striae in abdomen, thighs and armpits, weakness of proximal muscles, capillary fragility, and generalized joint and muscle pain for the past five years. A functional study of the pituitary–adrenal axis showed the following results: plasma cortisol levels of 27 and 23μg/dL at 8 and 23h, respectively, UFC of 160 and 167μg/24h on two consecutive days, ACTH levels (8h) of 46 and 43pg/mL on two consecutive days (normal range, 9–55), and UFC after strong dexamethasone suppression (2mg every 6h for two days) of 193μg/24h. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pituitary gland showed no pathological findings, and a CT scan of the chest and abdomen revealed a right adrenal mass 4cm in diameter (Fig. 1). Finally, IPSS was performed, showing a central to peripheral gradient >6 two minutes after administration of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) (Table 1). Based on this result, patient was diagnosed having Cushing disease on January 2010 and underwent transsphenoidal surgery, in which a 2-mm microadenoma was found and totally resected. Histological study of the specimen was not available. After surgery, the patient experienced no clinical improvement, and functional assessment 30 days after surgery confirmed persistent hypercortisolism (UFC levels of 337 and 400μg/24h). In November 2010, the patient was referred to our center, where repeat testing showed the following results: plasma cortisol levels at 8 and 23h of 27 and 28μg/dL (first day) and 26 and 26μg/dL (second day), UFC levels of 778μg/24h (normal range, <120; by chemiluminescence) and ACTH levels (8h) of 24 and 25pg/mL (normal range, 9–55). UFC levels changed a little after strong dexamethasone suppression (720μg/24h, a 7% decrease) and stimulation with CRH resulted in minimum increases in ACTH (basal 27, peak of 28pg/mL) and cortisol (basal 26, peak of 29μg/dL). These results led to diagnose Cushing syndrome due to ectopic ACTH secretion and accounted for the lack of improvement after pituitary surgery.

Concomitant functional study of the adrenal mass revealed urinary metanephrine levels three- to five-fold higher than the upper normal limit (unfractionated metanephrines, 3.64mg/24h [normal range, <1]; normetanephrine, 2,194μg/24h [normal range, <440], and metanephrine, 1154μg/24h [normal range, <340]. Scintigraphic studies with both MIBG and 111In-octreotide showed deposition in the right adrenal gland only, which allowed for confirming diagnosis of pheochromocytoma and for ruling out other potential sources of ACTH.

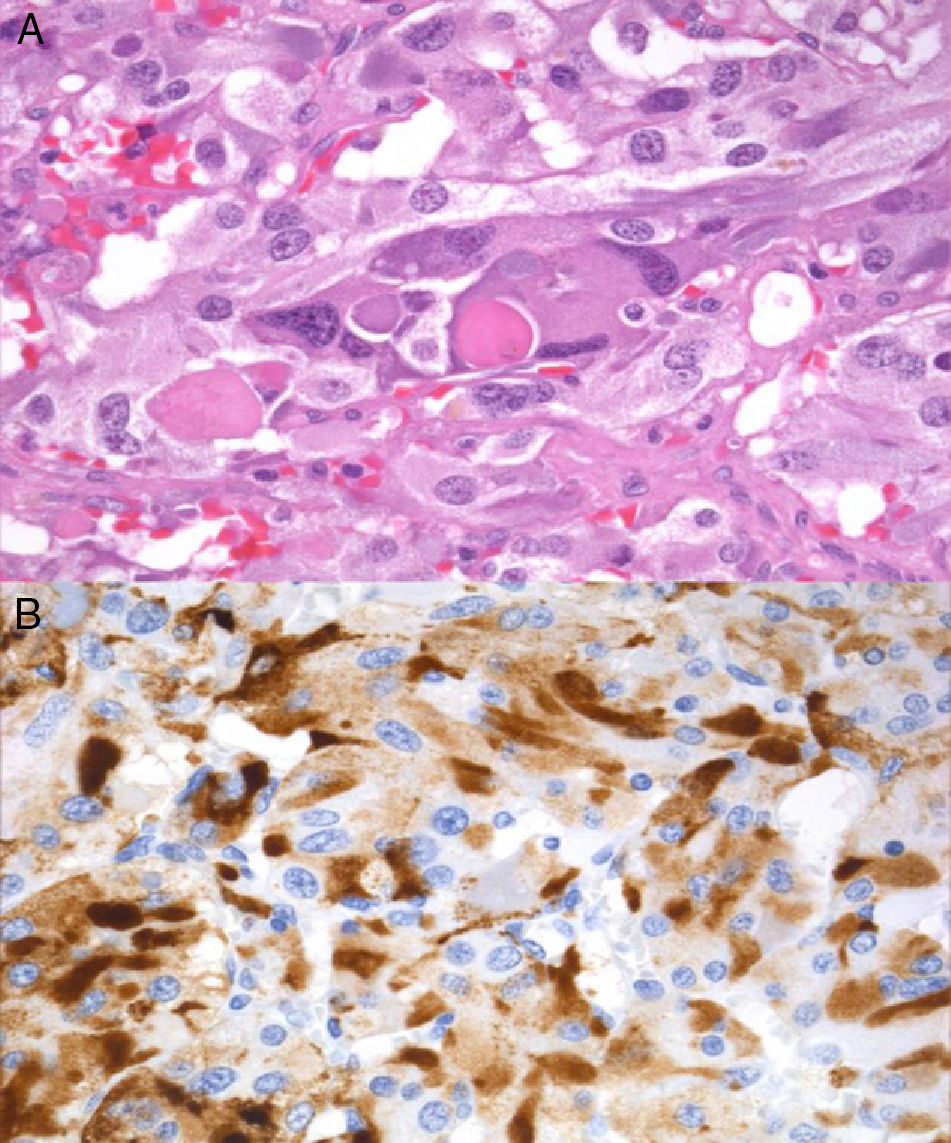

In February 2011, right laparoscopic adrenalectomy was performed after alpha-adrenergic blockade. After surgery, blood pressure and urinary metanephrine levels normalized (normetanephrine, 266μg/24h; metanephrine, 104μg/24h), and adrenal insufficiency occurred (basal plasma cortisol, 0.3μg/dL), suggesting complete resection of the ACTH source. The surgical specimen weighted 39.2g, and sectioning revealed a clearly outlined brown mass that compressed normal gland tissue. Microscopic examination showed wide central areas of necrosis with no cytological atypia, images of vascular invasion or extracapsular extension, and immunohistochemistry was positive for chromogranin, S100, and EMA.

Immunoreactivity for ACTH (Fig. 2) supported diagnosis of ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma. No mutations were found in the VHL, RET, and SDHB genes.

The first case of ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma was reported by Neff in 1942.6 Sixty five additional cases have been reported since then in the literature, two of them in Spain.7,8 In the Nijhoff review9 of 24 cases, age at presentation varied widely (26–74 years), women were mostly affected, and tumor size ranged from 2 and 6cm. A majority of patients had no symptoms of adrenergic overproduction, and almost all of them had ACTH levels above the normal range (342±207pg/mL) and a severe Cushing syndrome with hypokalemia (70%) and diabetes (90%). Only four cases of ACTH-secreting paragangliomas (two in the nasosinusal region and one each in the cervical and abdominal regions) have been reported to date, and no malignant paraganglioma has been reported.

According to literature, our patient had a relatively large lesion and mild HBP as the only sign of adrenergic overproduction. By contrast, unlike most reported cases, ACTH levels were within the normal range and the patient had a Cushing syndrome of moderate severity without diabetes, hypokalemia or edema.

When Cushing disease is suspected, persistence of hypercortisolism after pituitary surgery, as occurred in our patient, should lead to reconsider etiological diagnosis and review the results of functional tests. Several factors contributed to the wrong initial diagnosis in our case: including the ACTH-dependent nature of Cushing syndrome, which distracted attention from the adrenal gland, the initial urinary free cortisol levels (160 and 167μg/mL), and lack of suppression after strong dexamethasone challenge, which suggested an ectopic rather than pituitary origin, as well as wrong interpretation of IPSS.10 IPSS is the most accurate procedure to identify the source of ACTH secretion in the ACTH-dependent Cushing syndrome, and its result prevails over those of other diagnostic procedures in the event of discrepancy. A central to peripheral gradient ≥2:1 at baseline or ≥3:1 following CRH stimulation suggests pituitary ACTH secretion. Adequate interpretation should be done in a state of hypercortisolism to avoid the risk of false positives resulting from functional recovery of corticotroph cells and, thus, of their capacity to respond to CRH. Concordant results are usually obtained at most time points during the test: presence of gradient at a single time point in the absence of any incident during the test, although difficult to explain, should be considered as a false positive and should not condition overall interpretation of the test. In the event of doubt, however, it is recommended to repeat the procedure or to use other diagnostic tests.

In conclusion, although ACTH-secreting pheochromocytoma is an uncommon condition, it should be considered in any patient with an ACTH-dependent Cushing syndrome who has an adrenal lesion. Awareness of limitations of the different diagnostic procedures contributes to minimize diagnostic errors and inadequate treatments.

Please cite this article as: Martín Jiménez ML, Palacios García N, Salas Antón C, Armengod Grao L, Aller Pardo J. Feocromocitoma productor de corticotropina. Endocrinol Nutr. 2013;60:418–420.