Thyroid-associated paraganglioma (TAP) is a cervical paraganglioma adjacent to the thyroid gland or intrathyroidal. It originates from the inferior laryngeal paraganglia, located along the recurrent laryngeal nerve on the lateral margin of the cricoid cartilage in the cricothyroid membrane. The paraganglioma moves downwards to rest next to the thyroid, or the inferior laryngeal paraganglia may be part of the thyroid capsule and the paraganglioma may become intrathyroidal.1,2 We present the unusual case of a female patient with a nodular goiter who was diagnosed with TAP based on the cytology of the lesion.

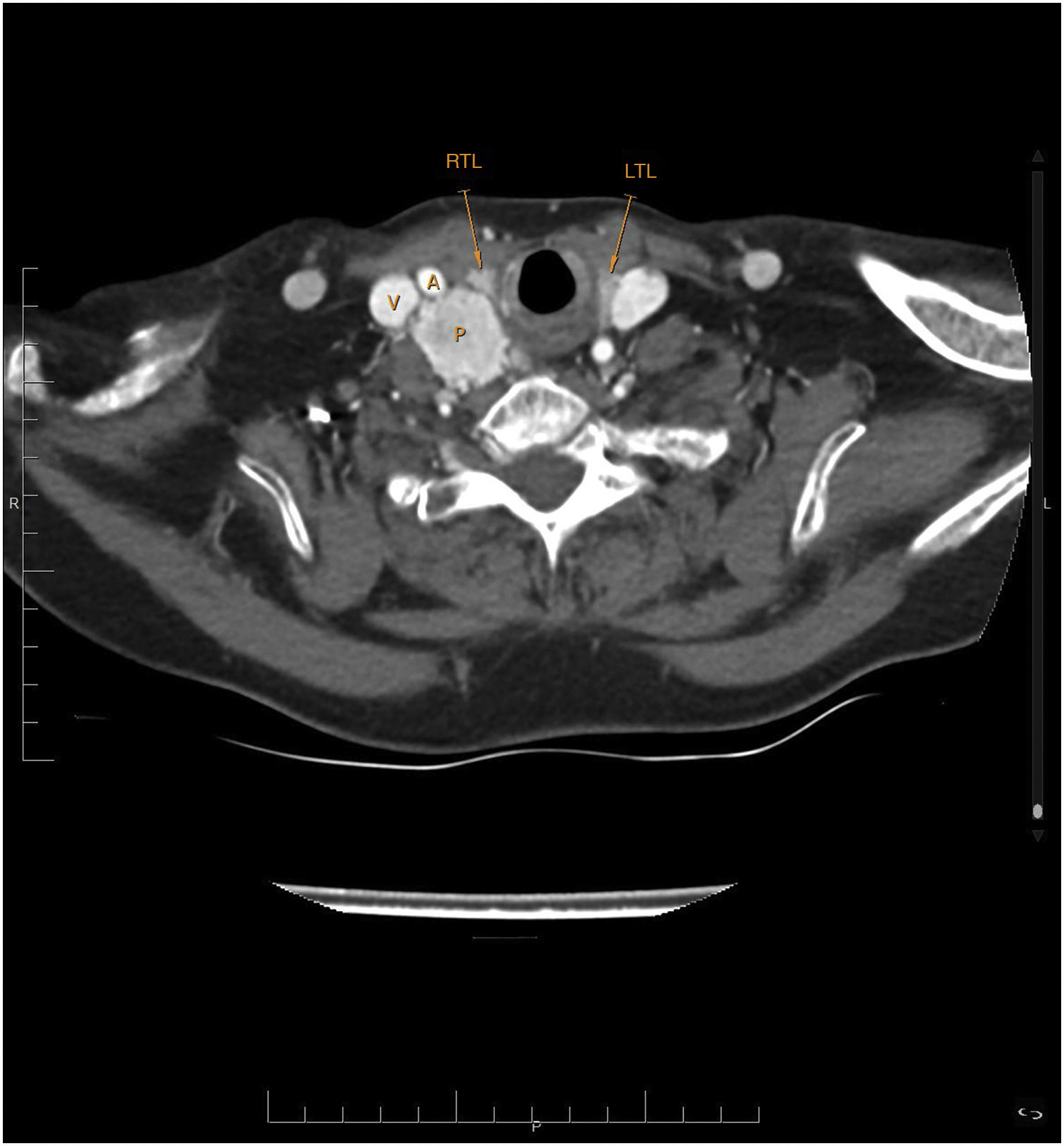

This was a 74-year-old woman referred from oncology after investigation of colon cancer with liver metastases revealed a goiter. The patient herself acknowledged that she had been aware of having a multinodular goiter for over ten years. She had no family history of goiter nor had she received neck radiotherapy. She was diagnosed with autoimmune hypothyroidism and was being treated with levothyroxine sodium 50 μg/day. She had been periodically monitored at another hospital, with normal thyrotropin values and follow-up neck ultrasound scans, which we were unable to obtain. No goiter cytology study had ever been performed. The patient claimed to have no local compressive symptoms. Physical examination revealed an irregular goiter, predominantly on the right, without lymphadenopathy. The ultrasound showed a multinodular goiter consisting in the right lobe of two isoechoic solid nodules of 18 × 11 × 22 mm and 11 × 13 × 18 mm, and a well-defined, slightly hypoechoic and hypervascular solid nodule 25 × 28 × 32 mm, and in the left lobe, a solid isoechoic nodule of 15 × 11 × 23 mm; no lymphadenopathy was observed. Puncture performed for cytology of the dominant nodule, the one with the highest suspicion of malignancy, revealed cell aggregates made up of cells with clear cytoplasm, with a trabecular pattern and scant cytological atypia, positive immunohistochemistry for synaptophysin and S100 in peritrabecular sustentacular cells negative for CK AE1-3, thyroglobulin, TTF1 and calcitonin; the cytology diagnosis was compatible with paraganglioma. A second puncture of the same nodule produced the same result. The patient had no family history suggestive of paraganglioma or arterial hypertension. Computerised tomography of the neck, chest and abdomen did not identify any paragangliomas additional to the one in the patient’s neck (Fig. 1), which was described as a solid nodule of 30 × 25 × 33 mm, with intense contrast uptake and moderately irregular margins, located adjacent to and broadly in contact with the right thyroid lobe. Plasma metanephrine levels were normal. Study of the succinate dehydrogenase gene was negative. In view of the patient’s associated disease and the lack of symptoms related to the neck paraganglioma, a “wait and see” management strategy was decided on. At the 6-month follow-up, no changes were noted in the tumour.

Paragangliomas are slow-growing tumours that originate in the extra-adrenal paraganglia of the autonomic nervous system. Head and neck paragangliomas represent 0.012%–0.6% of all tumours1,3 and originate in the parasympathetic tissue,2,4 with 80% of cases located in the carotid body and glomus jugulare, and less frequently in the tympanic plexus of the middle ear and vagus nerve. Paragangliomas of the nasal cavity, orbit, larynx and those associated with the thyroid are very unusual.2,3,5

Cases of TAP are rare, with about fifty reported since they were first described in 1964.3 The diagnosis tends to be made in middle-aged patients (around the age of 50) without thyroid dysfunction, with a clear predominance in women, based on a relatively large thyroid nodule, generally more than 3 cm in size, which is then treated surgically. On ultrasound it appears as a hypoechoic solid nodule with intra- and perinodular hypervascularisation.1–3,6 In rare cases it is diagnosed in a preoperative cytology study because it is confused with a follicular or medullary neoplasm, or the report is of insufficient material.2,3,6–8 The microscopic characteristics of paraganglioma are similar to other neuroendocrine tumours, particularly medullary thyroid carcinoma, but they are positive for synaptophysin and S100, and negative for calcitonin.1,2,8

Treatment of TAP is usually surgical, as in most cases no preoperative diagnosis has been made.1 The extent of the surgery is usually limited to excision of the tumour or hemithyroidectomy. Strong adhesions and even infiltrations to the adjacent tissue lead to a high incidence of surgical complications such as bleeding and recurrent paralysis.1–3

Between 4% and 16% of head and neck paragangliomas are malignant, metastasising to non-neuroendocrine tissues, usually lymph nodes, lung, liver, bone and skin.3 To our knowledge, there have only been two cases of TAP with lymph node metastases and one with lymph node and liver metastases.3,9 However, routine lymphadenectomy and/or follow-up of patients post-surgery is not recommended unless they are hereditary cases.1–3,5,8

Hyperfunctionality occurs in 1%–3% of paragangliomas located in the head and neck, and there is only one reported case of hyperfunctional TAP,10 but screening for hypersecretion of catecholamines is still recommended.1

The coexistence of other paragangliomas in a patient with TAP occurs in 9%–14% of cases, the most likely location being in the carotid body and/or along the vagus nerve. Computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis or positron emission tomography with 18F-DOPA, or even better if possible with 68Ga-DOTA, is therefore recommended to identify these lesions and avoid confusing them with metastases or postoperative recurrences.1–3,5,11

123I/131I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) and 111In-pentetreotide (octreoscan) scintigraphy scans are no longer recommended for this purpose due to their poorer diagnostic efficacy.11

At least 30% of paragangliomas located in the head and neck are thought to be caused by a germline mutation. In these cases, multiplicity, malignancy and association with other tumours such as pheochromocytomas are more common.3 Study for mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase genes is recommended,2,3 especially if the immunohistochemical staining is negative for succinate dehydrogenase B, as this indicates that some mutation may be present.8

FundingThis research received no specific aid from any public or private sector agencies or non-profit organisations.

AuthorshipLuis García Pascual: conception of the study, data acquisition and analysis, interpretation of results, writing of the draft and approval of the final version.

Clarisa González Mínguez: data acquisition and analysis, critical review of the draft and approval of the final version.

Andrea Elías: data acquisition and analysis, critical review of the draft and approval of the final version.

Please cite this article as: García Pascual L, González Mínguez C, Elías Mas A. Paraganglioma asociado al tiroides. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:288–290.