The selection of the most appropriate formula in long-term home enteral nutrition is a controversial issue. Our objective was to study a high protein hypercaloric enteral nutrition formula in patients with long-term feeding (180 days).

MethodsProspective observational multicenter real-life study with high-protein hypercaloric formula (2kcal/ml and 20% protein). General, anthropometric, analytical and quality of life data were collected by visual analog scale of the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions at the beginning, 60, 120 and 180 days. Gastrointestinal tolerance was assessed with a visual analog scale and Bristol Stool Scale and the risk of malnutrition was assessed using NRS-2002.

Results51 patients (88.2% men, mean age 62.0 years), with oncological diseases in 72.5%. No differences in anthropometric data were observed, although the percentage of patients at risk of malnutrition according to NRS 2002 was reduced from 75% to 8.3% (p<0.0001). No differences were observed in albumin, prealbumin, transferrin, lymphocytes or hematocrit. The quality of life improved from 3.84 (1.27) to 5.37 (1.12) on the visual analog scale (p<0.0001). A reduction in gastrointestinal symptoms was observed throughout the period of enteral nutrition. Both the number and percentage of stools considered normal according to the Bristol scale remained stable.

ConclusionOur study supports that the use of high-protein hypercaloric formulas during a 6-month nutritional treatment allows an adequate nutritional evolution without risk of dehydration and with a good tolerance, even improvement of gastrointestinal symptoms, and can contribute to an improvement in the quality of lifetime.

La selección de la fórmula más adecuada en nutrición enteral domiciliaria a largo plazo es un tema controvertido. Nuestro objetivo fue estudiar una fórmula hipercalórica hiperproteica en pacientes con alimentación exclusivamente con sonda a largo plazo (180 días).

MétodosEstudio multicéntrico observacional prospectivo en vida real con fórmula hipercalórica hiperproteica (2kcal/ml y 20% de proteínas). Se recogieron datos generales, antropométricos, analíticos y de calidad de vida mediante escala analógica visual del European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions al inicio, 60, 120 y 180 días. La tolerancia gastrointestinal se evaluó con una escala analógica visual y escala de heces de Bristol y la valoración del riesgo de desnutrición mediante NRS-2002.

ResultadosUn total de 51 pacientes (88,2% varones, edad media de 62,0 años), con patología oncológica en el 72,5%. No hubo diferencias en datos antropométricos, aunque sí se redujo el porcentaje de pacientes con riesgo de desnutrición del 75 al 8,3% (p<0,0001). No se observaron diferencias en albúmina, prealbúmina, transferrina, linfocitos o hematocrito. La calidad de vida mejoró de 3,84 (1,27) a 5,37 (1,12) en la escala analógica visual (p<0,0001). Se observó una reducción de la sintomatología gastrointestinal a lo largo del seguimiento. Tanto el número como el porcentaje de deposiciones consideradas normales según la escala de Bristol se mantuvieron estables.

ConclusiónNuestro estudio apoya que el empleo de fórmulas hipercalóricas hiperproteicas durante un tratamiento nutricional a 6 meses permite una adecuada evolución nutricional sin riesgo de deshidratación y con una buena tolerancia, incluso mejoría de sintomatología gastrointestinal, y puede contribuir a una mejora en la calidad de vida.

The selection of the most adequate enteral nutrition (EN) formula for long-term home enteral nutrition is subject to controversy. Although most patients may benefit from a standard polymeric, normocaloric and normoprotein standard formula (preferably with fiber), many studies indicate that, in critical patients, in postoperative periods or in situations characterized by metabolic stress, hyperprotein and hypercaloric formulas improve the nutritional status of the patient, so reducing the risk of malnutrition and markedly improving the nutritional and anthropometric parameters.1–5 In patients with multiple disease conditions, the current nutritional recommendations of 27kcal/kg body weight and more than 1g of protein per kg6 may sometimes be difficult to achieve through standard formulas. In the case of patients on long-term home nutritional treatment, the use of a hypercaloric formula may offer some advantages. For example, the increased concentration of the formula could allow for a reduction of the administered volume and therefore of the time needed for administration, so making feeding easier for patients and/or caregivers. In addition, the lesser volume could reduce gastrointestinal discomfort derived from abdominal bloating secondary to the administration of larger volumes. On the other hand, the use of these formulas could compromise adequate patient hydration.

The present study was carried out to assess the evolution of the nutritional parameters and tolerance during the period of use of a hypercaloric, hyperprotein enteral nutrition formula in patients on exclusive long-term tube feeding (180 days). As secondary objectives, an analysis was made of patient quality of life, the effect upon bowel rhythm, and stool consistency.

MethodsA multicenter, prospective, real-life observational study was made of patients receiving long-term home enteral nutrition through a gastrostomy tube or a nasogastric tube. The centers included in the study were invited to participate by the Principal Investigator, but no randomization method was used, since this was a real-life observational study. The co-investigators were asked to consecutively enter all patients meeting the inclusion criteria during the study period (1 April 2016 to 1 April 2017): patients over 18 years of age prescribed with enteral nutrition (via nasogastric tube or gastrostomy) and with an expected duration of feeding of over 8 weeks. The patient or his/her primary caregiver was required to be able to understand the study and to be fully free to participate in it, and to sign the informed consent. Pregnancy, an estimated survival of less than 90 days, the presence of severe intestinal disease, gastric ulcer, gastritis, diarrhea, gastroparesis, vomiting, gastroesophageal reflux, abdominal pain, antibiotic treatment in the previous 7 days, treatment with prokinetic agents during the study phase, and allergy or intolerance to any of the ingredients of the enteral formula were regarded as exclusion criteria. All patients were prescribed with the treatment required to meet their energy and macronutrient needs according to routine clinical practice at the participating centers. The high-calorie, high-protein formula used to meet these needs had a caloric density of 2kcal/ml and was composed of 20% proteins (10g/100ml of milk proteins), 35% carbohydrates (17.5g/100ml dextrinomaltose) and 45% fats (10g/100ml rapeseed and sunflower oils, medium-chain triglycerides [MCTs] and fish oil).

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León (Spain) on 27 October 2015 (approval number 2015/1615), and informed consent was requested from all the participants or their legal representatives. Sample size was predetermined using the Ene3.0 application. Assuming a 10% loss rate, a total of 30 patients were initially considered for recruitment.

A paper-format case report form (CRF) was used to record the data. After obtaining informed consent from the participants and checking the inclusion and exclusion criteria, data on affiliation (age and gender), reason for prescription of enteral nutrition and the dose and route of administration, as well as baseline anthropometric characteristics (height, weight, weight change in the 3 months prior to recruitment, arm and calf circumference) and the Barthel index on basic activities of daily living were also collected at the time of the recruitment visit.7 Laboratory measurements of albumin, prealbumin, transferrin, lymphocytes, hemoglobin and hematocrit were obtained according to standard practice at each participating center. Quality of life was assessed using the visual analogue scale (VAS) of the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D).8

The subsequent visits took place under conditions of standard clinical practice at 60, 120 and 180 days after the start of treatment. The same anthropometric, quality of life and biochemical data were collected at these visits. Gastrointestinal tolerance was assessed using a subjective perception test (visual analogue scale), where the degree of gastrointestinal manifestations is scored from 0 (absent) to 4 (very severe) referring to the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, regurgitation, constipation, diarrhea, flatulence, abdominal bloating and abdominal pain. Symptoms were regarded as mild if present but not bothersome; moderate if frequently bothersome but without interfering with daily activities or sleep; severe if sufficiently bothersome to interfere with daily activities or sleep; and very severe if requiring medical attention. The number and type of bowel movements were recorded using the Bristol stool scale. Types 4 and 5 were considered normal.9 The risk of malnutrition was assessed using the NRS-2002 scale.10

All data were entered in a database specifically created for the study using ACCESS-SQL 2010. Data analysis was only performed for existing data, with no replacement of missing data. The statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS version 24 statistical package. Central tendency statistics were used to describe the variables (mean, standard deviation [SD], 95% confidence interval [95%CI], minimum and maximum), since normality testing showed the data to exhibit a normal distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests). A linear mixed model for repeated measures was used to explore significant differences during the treatment period (visits 1, 2, 3 and 4). The significance level used was 5% (p<0.05).

ResultsFifty-one patients were enrolled in the study: 6 females (11.8%) and 45 males (88.2%), with a baseline mean Barthel index of 48.8 (SD 46.3). All the initially enrolled patients completed all the study visits. Oncological disease was the main indication in 72.5% of the cases (37 patients), while the remaining 14 patients had neurological diseases. Only four patients had a nasogastric tube while 92.2% received nutrition through a gastrostomy. The most commonly used formula contained fiber (1.5g/100ml) in 82.4% of the cases, and the equivalent without fiber was chosen in 9 patients at the discretion of the supervising physician.

The mean age of the patients administered nutritional therapy was 62.0 years (SD 13), with a baseline weight of 68.3kg (SD 12.5) and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 24.0kg/m2 (SD 3.6). The mean weight loss in the previous three months was 5.5kg (SD 5.9), representing 7.4% of the baseline weight (SD 6.0). The arm circumference was 27.0cm (SD 6.6) and that of the calf 33.8cm (SD 8.4).

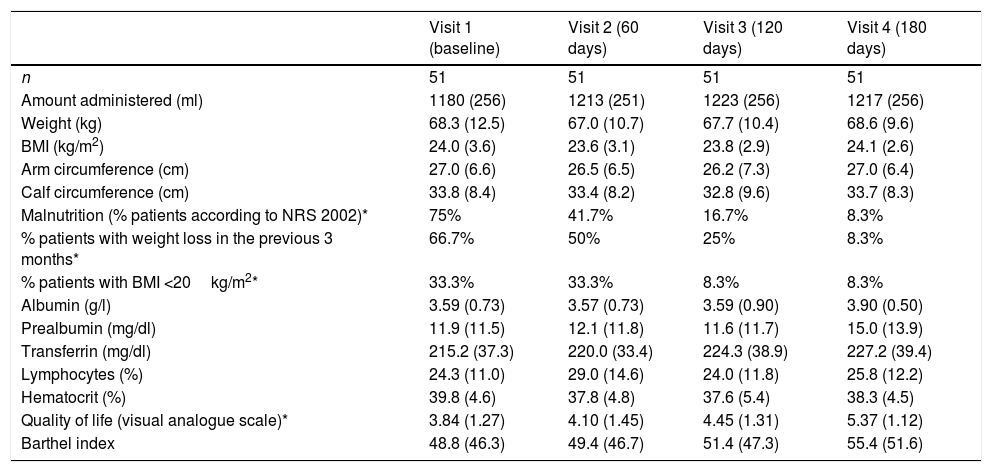

Table 1 shows the amount of nutrition administered over follow-up. The patients received an average of 31.9, 32.8, 33.1 and 32.9kcal/kg/day at each visit, with no significant differences between them. There were no statistically significant or clinically relevant differences in anthropometric data over follow-up (Table 1), though a decrease was recorded in the percentage of patients at risk of malnutrition according to the NRS 2002 scale (p<0.0001). Regarding the time course of the biochemical parameters, no significant differences were observed during follow-up regarding albumin, prealbumin, transferrin, lymphocytes or hematocrit.

Evolution of the clinical, anthropometric and biochemical parameters.

| Visit 1 (baseline) | Visit 2 (60 days) | Visit 3 (120 days) | Visit 4 (180 days) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 |

| Amount administered (ml) | 1180 (256) | 1213 (251) | 1223 (256) | 1217 (256) |

| Weight (kg) | 68.3 (12.5) | 67.0 (10.7) | 67.7 (10.4) | 68.6 (9.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 (3.6) | 23.6 (3.1) | 23.8 (2.9) | 24.1 (2.6) |

| Arm circumference (cm) | 27.0 (6.6) | 26.5 (6.5) | 26.2 (7.3) | 27.0 (6.4) |

| Calf circumference (cm) | 33.8 (8.4) | 33.4 (8.2) | 32.8 (9.6) | 33.7 (8.3) |

| Malnutrition (% patients according to NRS 2002)* | 75% | 41.7% | 16.7% | 8.3% |

| % patients with weight loss in the previous 3 months* | 66.7% | 50% | 25% | 8.3% |

| % patients with BMI <20kg/m2* | 33.3% | 33.3% | 8.3% | 8.3% |

| Albumin (g/l) | 3.59 (0.73) | 3.57 (0.73) | 3.59 (0.90) | 3.90 (0.50) |

| Prealbumin (mg/dl) | 11.9 (11.5) | 12.1 (11.8) | 11.6 (11.7) | 15.0 (13.9) |

| Transferrin (mg/dl) | 215.2 (37.3) | 220.0 (33.4) | 224.3 (38.9) | 227.2 (39.4) |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 24.3 (11.0) | 29.0 (14.6) | 24.0 (11.8) | 25.8 (12.2) |

| Hematocrit (%) | 39.8 (4.6) | 37.8 (4.8) | 37.6 (5.4) | 38.3 (4.5) |

| Quality of life (visual analogue scale)* | 3.84 (1.27) | 4.10 (1.45) | 4.45 (1.31) | 5.37 (1.12) |

| Barthel index | 48.8 (46.3) | 49.4 (46.7) | 51.4 (47.3) | 55.4 (51.6) |

With regard to patient quality of life, there appeared to be improvements over the course of nutritional therapy (Table 1) according to the VAS scores. The difference between the initial and final visits was statistically significant (p<0.0001).

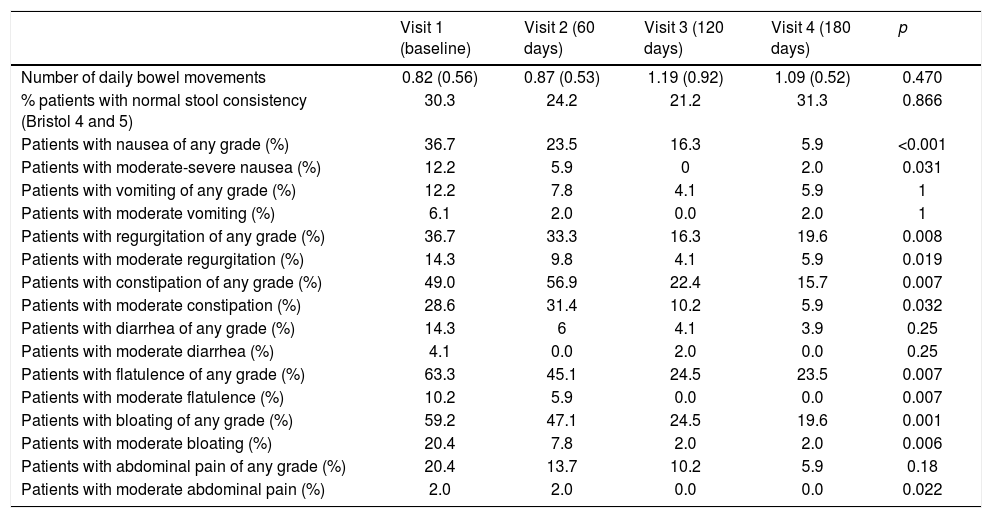

With regard to the gastrointestinal symptoms, no severe or very severe problems were reported in any of the patients. Table 2 describes the total percentage of patients with symptoms and the percentage of patients with moderate or moderate-severe symptoms. The number of daily bowel movements remained stable throughout the study period, with approximately one bowel movement a day. The percentage of patients with stools considered normal according to the Bristol stool scale likewise showed no significant changes. A statistically significant decrease in gastrointestinal symptoms was observed during the enteral nutrition period in terms of nausea, regurgitation, constipation, flatulence, bloating and pain, but no changes in vomiting or diarrhea were recorded. Abdominal pain showed a tendency to decrease, with significance being reached in those patients presenting moderate symptoms.

Gastrointestinal symptoms.

| Visit 1 (baseline) | Visit 2 (60 days) | Visit 3 (120 days) | Visit 4 (180 days) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of daily bowel movements | 0.82 (0.56) | 0.87 (0.53) | 1.19 (0.92) | 1.09 (0.52) | 0.470 |

| % patients with normal stool consistency (Bristol 4 and 5) | 30.3 | 24.2 | 21.2 | 31.3 | 0.866 |

| Patients with nausea of any grade (%) | 36.7 | 23.5 | 16.3 | 5.9 | <0.001 |

| Patients with moderate-severe nausea (%) | 12.2 | 5.9 | 0 | 2.0 | 0.031 |

| Patients with vomiting of any grade (%) | 12.2 | 7.8 | 4.1 | 5.9 | 1 |

| Patients with moderate vomiting (%) | 6.1 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 1 |

| Patients with regurgitation of any grade (%) | 36.7 | 33.3 | 16.3 | 19.6 | 0.008 |

| Patients with moderate regurgitation (%) | 14.3 | 9.8 | 4.1 | 5.9 | 0.019 |

| Patients with constipation of any grade (%) | 49.0 | 56.9 | 22.4 | 15.7 | 0.007 |

| Patients with moderate constipation (%) | 28.6 | 31.4 | 10.2 | 5.9 | 0.032 |

| Patients with diarrhea of any grade (%) | 14.3 | 6 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 0.25 |

| Patients with moderate diarrhea (%) | 4.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.25 |

| Patients with flatulence of any grade (%) | 63.3 | 45.1 | 24.5 | 23.5 | 0.007 |

| Patients with moderate flatulence (%) | 10.2 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.007 |

| Patients with bloating of any grade (%) | 59.2 | 47.1 | 24.5 | 19.6 | 0.001 |

| Patients with moderate bloating (%) | 20.4 | 7.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.006 |

| Patients with abdominal pain of any grade (%) | 20.4 | 13.7 | 10.2 | 5.9 | 0.18 |

| Patients with moderate abdominal pain (%) | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.022 |

Studies on the efficacy and tolerability of long-term enteral nutrition in adults are few; it is therefore difficult to compile the data needed to allow for the evidence-based selection of a long-term enteral formula. Moreover, in real-life clinical practice in patients receiving home nutrition, hypercaloric formulas have often been viewed with mistrust by some professionals due to concerns about poor gastrointestinal tolerance and a negative impact upon the hydration status of patients administered exclusive long-term enteral nutrition.

Although most patients could benefit from a standard polymeric, normocaloric and normoproteic formula – preferably with fiber – hypercaloric hyperproteic formulas could help to more adequately cover the nutritional requirements of the patient. In patients with multiple disease conditions, the current nutritional recommendations of 27kcal/kg body weight and more than 1g of protein per kg6 may sometimes be difficult to achieve through standard formulas. The increased concentration of the hypercaloric, hyperproteic formula could allow for a reduction of the administered volume and therefore of the time needed for administration, so making feeding easier for patients and/or caregivers. In addition, the lesser volume could reduce the gastrointestinal discomfort derived from abdominal bloating secondary to the administration of larger volumes.

The objective of our study was to assess, under real-life clinical practice conditions, both the effectiveness of a hypercaloric, hyperproteic formula in terms of the evolution of nutritional parameters and the resolution of malnutrition, and its safety, evaluating tolerance during the consumption period and the risk of dehydration assessed by changes in hematocrit. The included patients were individuals with exclusive long-term enteral tube feeding (180 days).

The most recent home enteral nutrition data in Spain, corresponding to the NADYA registry,11 were obtained in a population slightly older than our own (71 versus 62 years of age). The most common cause of enteral nutrition in the NADYA registry was neurological disease associated with severe aphagia or dysphagia (59%), in contrast to our own series, where oncological disease was the main indication (in 72.5% of cases). This difference in indications may explain the younger age of our patients. The most significant finding in our series regarding the effectiveness of enteral nutrition was the observation of a statistically significant and clinically very relevant reduction in the percentage of patients considered to be at risk of malnutrition according to the NRS 2002, with a decrease from 75% to 8.3%. This was associated with a parallel reduction in the percentage of patients with weight loss in the previous three months and with a BMI <20kg/m2. These points are recorded as phenotypic criteria, together with loss of muscle mass, in the recent GLIM consensus on the diagnosis of malnutrition.12 However, our study was unable to record a diagnosis of malnutrition according to the GLIM, since the data were collected prior to the mentioned consensus, and muscle mass was not assessed.

The analyzed biochemical parameters remained stable throughout follow-up, with a slight and nonsignificant increase in prealbumin levels that could also be indicative of nutritional improvement. We consider the stability of hematocrit in the patients to be very relevant, since this was the parameter chosen to assess possible dehydration. Although few data are available on dehydration in patients receiving long-term enteral nutrition, an American publication13 reported that 37% of all patients require admission due to dehydration or malnutrition during treatment with enteral nutrition. This is not consistent with our own observations, however. It therefore may be affirmed that in our series the use of a hypercaloric formula did not favor patient dehydration, though it did contribute to improvements in patient nutritional status and to the prevention of malnutrition.

The fact that the patients improved their nutritional status with exclusive enteral nutrition and that we had no patient loss due to discontinuation of the formula suggests that overall tolerance during the 6 months of follow-up was high. Assessment of the gastrointestinal symptoms confirmed this favorable impression. No serious or very serious problems were reported in any of the patients, and there was a statistically significant reduction in gastrointestinal symptoms over the 6-month period of enteral nutrition in terms of nausea, regurgitation, constipation, flatulence, bloating and pain. The incidence of diarrhea was also reduced, though in this case statistical significance was not reached. Both the number and the percentage of stools considered to be normal according to the Bristol stool scale remained stable at the start and after 6 months of nutritional treatment.

The assessment of patient quality of life during enteral nutrition appears to be relevant to our study. In effect, the visual analogue scale showed significant improvement, and although the overall data are not good (as could be expected in patients with these characteristics, i.e., mainly oncological cases with no possibility of oral intake), the VAS score increased from 3.84 to an “approval” score of 5.37 points out of 10.

The most important limitation of our study is its prospective observational design, with no control group. It would have been interesting to be able to determine whether the observed nutritional improvement and tolerance would have been similar or not using a standard formula. Another limitation related to the assessment of patient quality of life is the fact that we used a general tool, such as the EuroQoL visual analogue scale. Although it would have been interesting to use specific questionnaires such as the NutriQoL,14 we considered that it would have required a longer time at the clinic. A faster alternative was therefore chosen, since this was not the primary objective of our study. With regard to the strengths of the study, mention should be made of the fact that it was a multicenter trial performed under real-life conditions, and that all the patients who started nutritional treatment continued it throughout the 6-month monitoring period. To our knowledge, this is the only study of these characteristics published to date, since the only identified similar study involved a much shorter follow-up period (8 weeks),15 included both outpatients and inpatients, and did not assess quality of life.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the use of hypercaloric, hyperproteic formulas, mostly with fiber, as nutritional treatment during a period of 6 months facilitates adequate nutritional progression without the risk of dehydration and with good tolerance. Such formulas even appear to improve the gastrointestinal symptoms, and may contribute to improved patient quality of life.

Financial supportThis study received support from Fresenius Kabi España for the statistical analysis of the data and the publication costs.

Conflicts of interestMaría D. Ballesteros-Pomar has received fees for lectures, consultancy or research studies from Fresenius Kabi, Nestlé Health Science, Abbot Nutrition, Nutricia and Vegenat. Patricia Sorribes-Carreras has received fees for lectures on dysphagia from Fresenius Kabi. She has no conflicts of interest in Nutrition. María Amparo Rodríguez-Piñera has received fees for clinical studies sponsored by Fresenius Kabi España. Antonio José Blanco-Orenes has participated in conferences with Novartis Farmaceutica S.A., Laboratorios Rovi S.A., Pfizer and Fresenius Kabi España. Laura Calles-Romero has received fees for conducting talks, collaborations and research projects from Abbott, Fresenius Kabi España, Nestlé Health Science, Nutricia, Persan and Adventia. Natalia C. Iglesias-Hernández has received fees for lectures from Nestlé Health Science, Takeda (formerly Shire), Fresenius Kabi España and Nutricia. She has also participated as a consultant and collaborator in studies of the aforementioned companies and of Abbott Nutrition and Persan Farma. M. Teresa Olivan-Usieto has no conflicts of interest in Nutrition. Francisca Payeras-Mas has received fees for lectures from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Fresenius Kabi, Lilly, NovoNordisk and Sanofi. She has served as a paid expert for NovoNordisk and has received a grant from Astra Zeneca. Margarita Viñuela-Benéitez has participated in clinical trials and has prepared review articles funded by Fresenius-Kabi. She has also attended training activities organized by Abbott. She has participated as a speaker in training activities and attended international scientific events funded by Nestlé. María Merino-Viveros has participated as a collaborator in studies for Fresenius Kabi España. Cristina Navea-Aguilera has participated in studies funded by Fresenius-Kabi and as a speaker in training activities funded by Nestlé. Josefina Olivares has participated in clinical trials for NovoNordisk, Lilly, Boehringer (Diabetes).

Please cite this article as: Ballesteros Pomar MD, Sorribes Carrera P, Rodriguez Piñera MA, Blanco Orenes AJ, Calles Romero L, Iglesias Hernández NC, et al. Estudio en vida real de efectividad de una fórmula hipercalórica hiperproteica en el mantenimiento y mejora del estado nutricional en pacientes con indicación de nutrición enteral a largo plazo. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:11–16.