Bariatric surgery aims to reduce weight and resolve the comorbidities associated with obesity. Few studies have assessed mid/long-term changes in lipid profile with sleeve gastrectomy versus gastric bypass. This study was conducted to assess and compare changes in lipid profile with each procedure after 60 months.

MethodsThis was an observational, retrospective study of analytical cohorts enrolling 100 patients distributed into two groups: 50 had undergone gastric bypass (GBP) surgery and 50 sleeve gastrectomy (SG) surgery. Total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglyceride (TG) levels were measured before surgery and at 1, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months. Weight loss and the resolution of dyslipidemia with each of the procedures were also assessed.

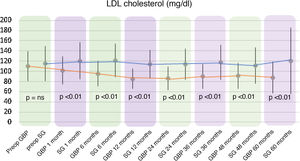

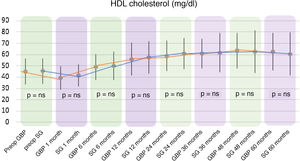

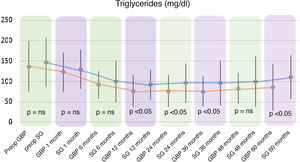

ResultsNinety-five of the 100 patients completed follow-up. At 60 months, TC and LDL levels had significantly decreased in the BPG group (167.42 ± 31.22 mg/dl and 88.06 ± 31.37 mg/dl, respectively), while there were no differences in the SG group. Increased HDL levels were seen with both procedures (BPG: 62.69 ± 16.3 mg/dl vs. SG: 60.64 ± 18.73 mg/dl), with no difference between the procedures. TG levels decreased in both groups (BPG: 86.06 ± 56.57 mg/dl vs. SG: 111.09 ± 53.08 mg/dl), but values were higher in the BPG group (P < .05). The percentage of overweight lost (PSP) was higher in the BPG group: 75.65 ± 22.98 mg/dl vs. the GV group: 57.83 ± 27.95 mg/dl.

ConclusionGastric bypass achieved better mid/long-term results in terms of weight reduction and the resolution of hypercholesterolemia as compared to sleeve gastrectomy. While gastric bypass improved all lipid profile parameters, sleeve gastrectomy only improved HDL and triglyceride levels.

La cirugía bariátrica tiene como objetivo la reducción del peso y la resolución de las comorbilidades asociadas a la obesidad. Los estudios que valoran la evolución del perfil lipídico comparando gastrectomía vertical y bypass gástrico a medio-largo plazo son escasos. Este estudio tiene como objetivo evaluar y comparar la variación del perfil lipídico con cada técnica a 60 meses.

MetodologíaEstudio observacional de cohortes analíticas retrospectivo que recogió 100 pacientes distribuidos en dos grupos, 50 intervenidos mediante bypass gástrico(BPG) y 50 mediante gastrectomía vertical(GV). Se determinó el colesterol total(CT), lipoproteínas de baja densidad(LDL), lipoproteínas de alta densidad(HDL) y triglicéridos(TG) preoperatoriamente y a 1,6,12,24,36,48,60 meses. También se evaluó la pérdida ponderal y resolución de dislipemias según la técnica.

ResultadosDe 100 pacientes, 95 completaron el seguimiento. A los 60 meses, el CT y LDL se redujeron significativamente en el grupo BPG (167,42 ± 31,22 mg/dl y 88,06 ± 31,37 mg/dl respectivamente), mientras que el grupo GV no obtuvo diferencias. Ambas técnicas mostraron un aumento del HDL (BPG: 62,69 ± 16,3 mg/dl vs GV: 60,64 ± 18,73 mg/dl), sin hallar diferencias entre los dos procedimientos. Los TG disminuyeron en ambos grupos, (BPG: 86,06 ± 56,57 mg/dl vs GV: 111,09 ± 53,08 mg/dl), siendo superiores los resultados del bypass (P < .05). El porcentaje de sobrepeso perdido(PSP) fue mayor en el grupo BPG: 75,65 ± 22,98 mg/dl vs grupo GV: 57,83 ± 27,95 mg/dl.

ConclusiónEl bypass gástrico obtuvo mejores resultados en cuanto a reducción del peso y resolución de hipercolesterolemia comparado con la gastrectomía vertical a medio-largo plazo. Mientras que el bypass gástrico mejoró todos los parámetros del perfil lipídico, la gastrectomía vertical sólo lo hizo con el HDL y triglicéridos.

Obesity is defined by the WHO1 as an abnormal or excessive accumulation of fat that can be harmful to health. There are numerous comorbidities associated with obesity such as diabetes, hypertension or dyslipidaemia, cardiovascular risk factors that cause greater morbidity and mortality in these patients.2

In the NHANES study,3 a common dyslipidaemic pattern was observed in obese patients characterised by increased triglycerides, elevated LDL-cholesterol, and decreased HDL cholesterol.

This pattern seems to be a consequence of the relationship between obesity and chronic hyperinsulinism, the latter being the result of a high-calorie diet and an increase in central fat. All of this fosters the development of insulin resistance.4

There are studies that relate the state of insulin resistance to an increase in total triglycerides (TG) or triglycerides contained in VLDL (very low-density lipoprotein). Increased plasma VLDL particles produces TG-rich LDL particles, giving rise to highly atherogenic “small dense LDL”. In addition, increased TG in HDL particles in states of insulin resistance facilitates their elimination and their consequent plasma decrease.4,5

Bariatric surgery is emerging as a therapeutic alternative for weight reduction when medical treatment fails. Currently, it is not only the most effective method in terms of long-term weight loss, but also for the control of comorbidities in obese patients. One such surgical procedure is sleeve gastrectomy (SG), a restrictive technique that has been gaining importance in recent years as an alternative to gastric bypass (GBP) for offering similar results in terms of weight loss and resolution of comorbidities.6

In the short term, GBP achieves weight loss in the region of 60%–70%, which is maintained at around 60% after 10 years. With this technique, a dyslipidaemia resolution or improvement rate of up to 93% is achieved.7 Regarding sleeve gastrectomy, weight loss is between 48%–61% at five years,8 and remission of dyslipidaemia in the short term is 75%.

Although there are numerous short-term studies that compare the lipid profile of obese patients who have undergone GBP or sleeve gastrectomy, there are not many medium- and long-term studies.

The objective of this study was to describe and compare variation in the lipid profile and weight evolution with GBP and SG 60 months after surgery.

Material and methodsThis was a retrospective, analytical, observational cohort study comparing SG and GBP with regard to lipid profile results. Two groups were designed in order of inclusion on the SG surgical waiting list.

The study was carried out at the General Surgery and Gastrointestinal System Department of the Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía [Santa Lucía University General Hospital], with data collected from consecutive patients who underwent bariatric surgery between 2011–2013, who completed a follow-up period of 60 months. All the patients who underwent surgery met the inclusion criteria established by the SECO (Sociedad Española de Cirugía de la Obesidad [Spanish Society of Bariatric Surgery])9 for the selection of candidates for bariatric surgery.

The study was approved by the centre's Independent Ethics Committee and all patients signed an informed consent for their inclusion in the study. In addition, all participants were given nutritional guidance and follow-up by a specialist in endocrinology and nutrition and by general surgery, with none of them presenting with malnutrition at 60 months.

Anthropometric and laboratory measurementsThe following anthropometric, clinical and laboratory parameters were evaluated preoperatively and at 1, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 months after surgery:

- -

Body mass index (BMI), ideal weight was calculated according to the Wan der Vael formula and the percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL). The criterion of success or failure of the procedure in terms of weight loss was established according to the criteria proposed by Baltasar et al.,10 which establish three categories of outcome: excellent (%EWL > 65% and BMI < 30 kg/m²); good or acceptable (%EWL 50%–65% and BMI 30−35 kg/m²); and failure (%EWL < 50% and BMI > 35 kg/m²).

- -

Complete remission of diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as HbA1c ≤ 6.5% and normalisation of fasting blood glucose (126 mg/dl) without pharmacological treatment for at least one year.11

- -

Hypercholesterolaemia was defined as total cholesterol (TC) > 200 mg/dl and/or LDL > 100 mg/dl and/or taking lipid-lowering treatment. The criteria for complete remission were not taking lipid-lowering medication and TC < 200 mg/dl and LDL < 100 mg/dl.12

- -

Hypertriglyceridaemia was defined as plasma TG levels > 200 mg/dl. The criteria for remission were not taking lipid-lowering medication and TG < 150 mg/dl.12

- -

Laboratory tests were conducted to measure total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol and triglycerides.

The GBP technique was performed by making a 20−30 ml gastric reservoir, establishing a length of 100−150 cm for both the alimentary limb and the biliopancreatic limb. The gastrojejunal anastomosis was performed in a mechanical end-to-side manner with a number 21 circular endostapler. Lastly, a linear endostapler was used for the loop foot, creating a mechanical side-to-side anastomosis with closure of the eyelet with a continuous absorbable monofilament suture.

The “sleeve gastrectomy” technique was performed by making a gastric tube using a 32 Fr bougie. After releasing the greater curvature of the stomach, a longitudinal section was made at 4−5 cm from the pylorus to the angle of His using a roticulator linear endostapler. The section line was reinforced with a continuous absorbable monofilament suture.

Both procedures were performed laparoscopically by the same surgical team.

Statistical analysisIn the descriptive analysis, quantitative variables were expressed in terms of mean and standard deviation. Qualitative variables were expressed in terms of frequency and percentage. The normality of the distribution of variables was verified using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

In the comparative analysis, the Student's t-test was applied for independent data with the quantitative variables in order to compare the two surgical techniques. The Student's t-test was also used for paired data in order to ascertain the evolution of the quantitative variables in each technique. Regarding the categorical variables of independent groups, the Chi-squared test was applied. When the necessary conditions for this test were not met, Fisher's exact test or McNemar's test was used as appropriate.

All comparative analyses were two-tailed. The minimum level of significance used was P < .05. The data were analysed with the SPSS® statistical program, version 17.

ResultsOf the 100 patients who started the study, 95 completed the 60-month follow-up. The GBP group achieved 100% follow-up, while the SG group brought it down to 95%, with 45 patients out of 50 completing the follow-up.

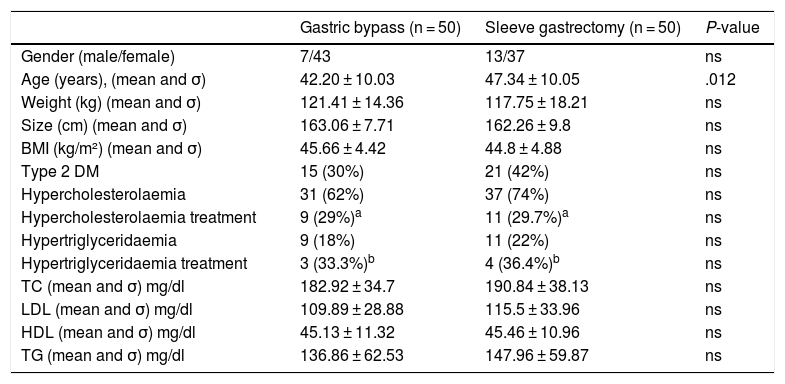

Both groups were comparable in preoperative variables except for age, which was higher in the SG group (Table 1).

Demographic and analytical variables and preoperative comorbidities.

| Gastric bypass (n = 50) | Sleeve gastrectomy (n = 50) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 7/43 | 13/37 | ns |

| Age (years), (mean and σ) | 42.20 ± 10.03 | 47.34 ± 10.05 | .012 |

| Weight (kg) (mean and σ) | 121.41 ± 14.36 | 117.75 ± 18.21 | ns |

| Size (cm) (mean and σ) | 163.06 ± 7.71 | 162.26 ± 9.8 | ns |

| BMI (kg/m²) (mean and σ) | 45.66 ± 4.42 | 44.8 ± 4.88 | ns |

| Type 2 DM | 15 (30%) | 21 (42%) | ns |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 31 (62%) | 37 (74%) | ns |

| Hypercholesterolaemia treatment | 9 (29%)a | 11 (29.7%)a | ns |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia | 9 (18%) | 11 (22%) | ns |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia treatment | 3 (33.3%)b | 4 (36.4%)b | ns |

| TC (mean and σ) mg/dl | 182.92 ± 34.7 | 190.84 ± 38.13 | ns |

| LDL (mean and σ) mg/dl | 109.89 ± 28.88 | 115.5 ± 33.96 | ns |

| HDL (mean and σ) mg/dl | 45.13 ± 11.32 | 45.46 ± 10.96 | ns |

| TG (mean and σ) mg/dl | 136.86 ± 62.53 | 147.96 ± 59.87 | ns |

BMI: body mass index; DM: diabetes mellitus; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; mg/dl: milligram/decilitre; ns: not significant; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides.

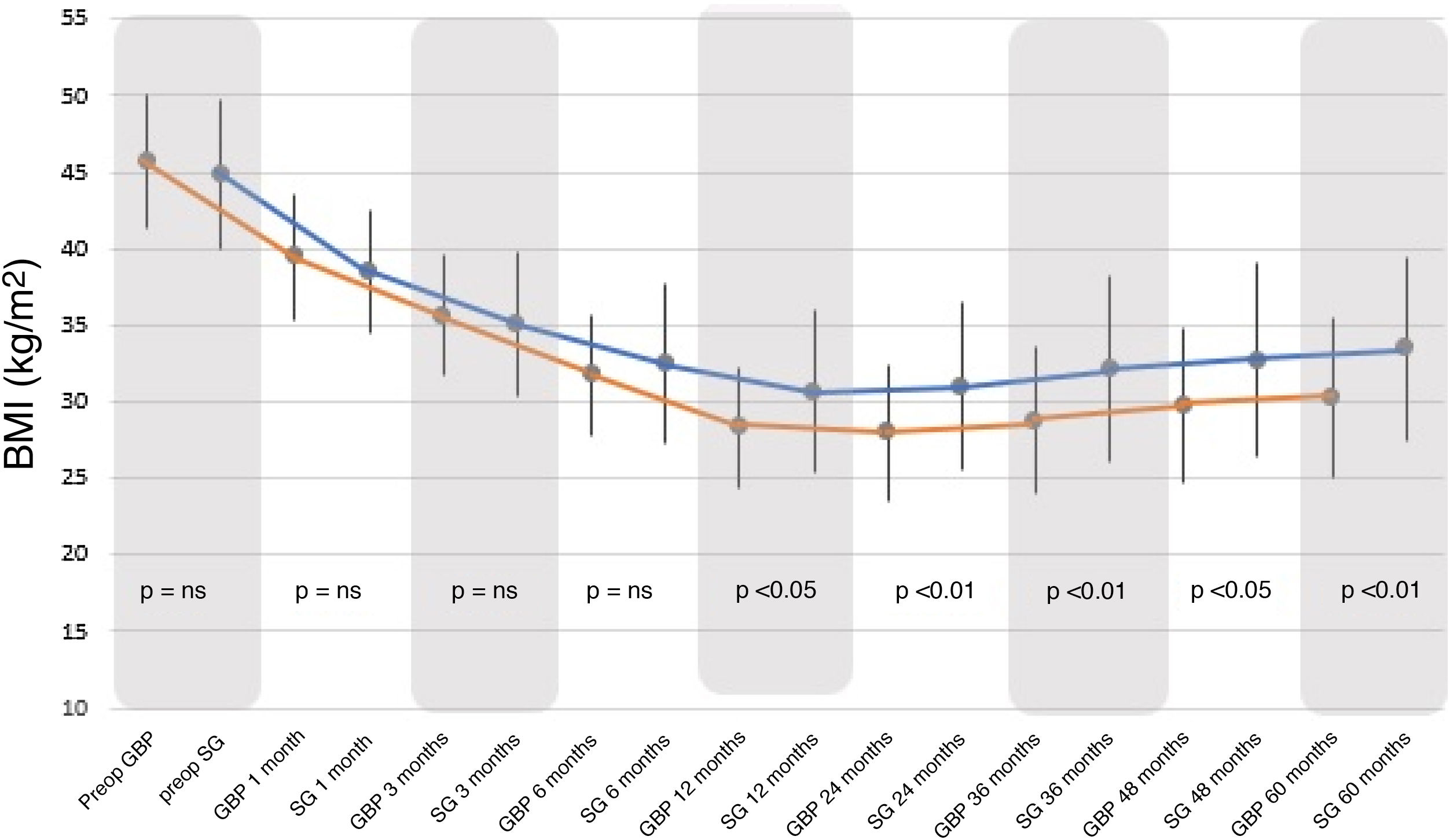

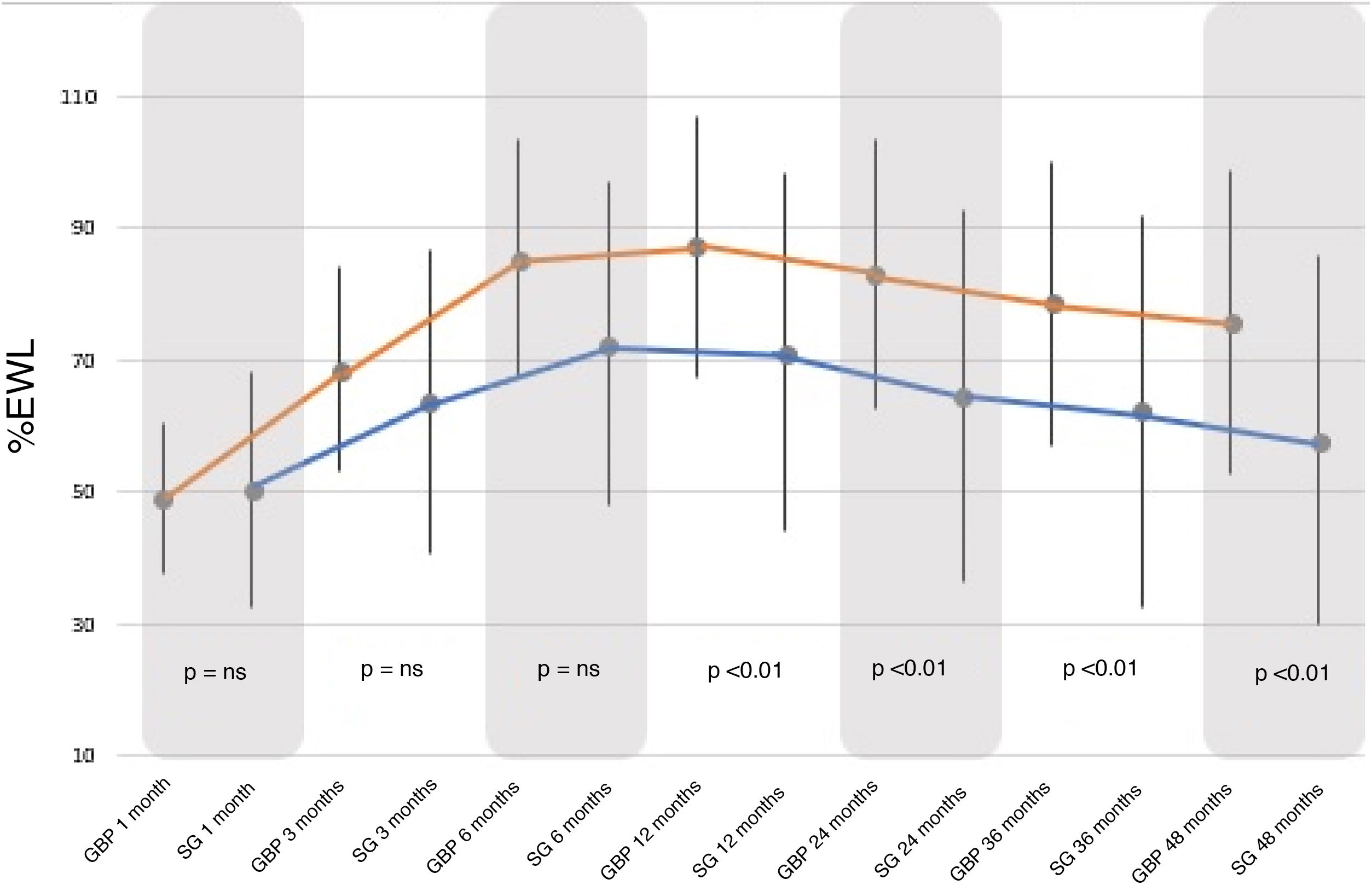

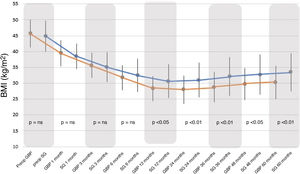

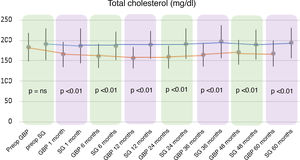

BMI decreased significantly with both surgical techniques from the first postoperative month, with a greater and statistically significant decrease seen with GBP from 12 months to the end of follow-up (Fig. 1).

Regarding the %EWL, it increased significantly in both groups, peaking between 12–24 months and then decreasing until the end of follow-up. The %EWL achieved at the end of the follow-up was higher in the GBP group (75.65 ± 2.98%) than in the SG group (57.83 ± 27.95%), with a P < .01 (Fig. 2).

When comparing both groups, there were no statistically significant differences between the BMI and %EWL results before 12 months, after which the GBP group demonstrated better results than the SG group (P < .01). Following the criteria proposed by Baltasar et al., the results obtained would be considered "excellent" for the GBP technique versus “good or acceptable” for the SG technique.

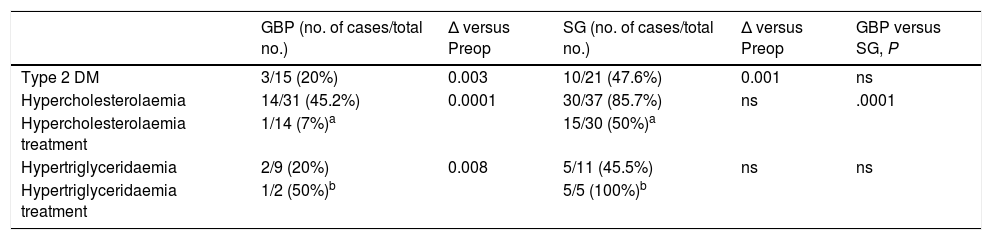

ComorbiditiesIn the GBP group, the DM remission percentage at 60 months was 80% (P < .05), while in the SG group it was just 52.4% (P < .01). When comparing both groups in terms of complete DM remission, no statistically significant differences were found.

At the end of the follow-up (60 months), 54.8% of patients in the GBP group met the complete remission criteria for hypercholesterolaemia (P < .001) compared to just 14.3% in the SG group (P = ns).

Regarding hypertriglyceridaemia, at 60 months, complete remission was observed in 80% of GBP patients (P < .01) and in 54.5% of SG patients (P = ns). When comparing both techniques in terms of complete remission of hypertriglyceridaemia, no statistically significant differences were found.

In the GBP group, only one patient with hypercholesterolaemia and one with hypertriglyceridaemia remained on pharmacological treatment at the end of follow-up. In contrast, the number of patients in the SG group receiving medical treatment for both hypertriglyceridaemia and hypercholesterolaemia at 60 months increased (Table 2).

Evolution of comorbidities at 60 months after surgery.

| GBP (no. of cases/total no.) | Δ versus Preop | SG (no. of cases/total no.) | Δ versus Preop | GBP versus SG, P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 2 DM | 3/15 (20%) | 0.003 | 10/21 (47.6%) | 0.001 | ns |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 14/31 (45.2%) | 0.0001 | 30/37 (85.7%) | ns | .0001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia treatment | 1/14 (7%)a | 15/30 (50%)a | |||

| Hypertriglyceridaemia | 2/9 (20%) | 0.008 | 5/11 (45.5%) | ns | ns |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia treatment | 1/2 (50%)b | 5/5 (100%)b |

DM: diabetes mellitus; GBP: gastric bypass; ns: not significant; Preop: preoperative; SG: sleeve gastrectomy.

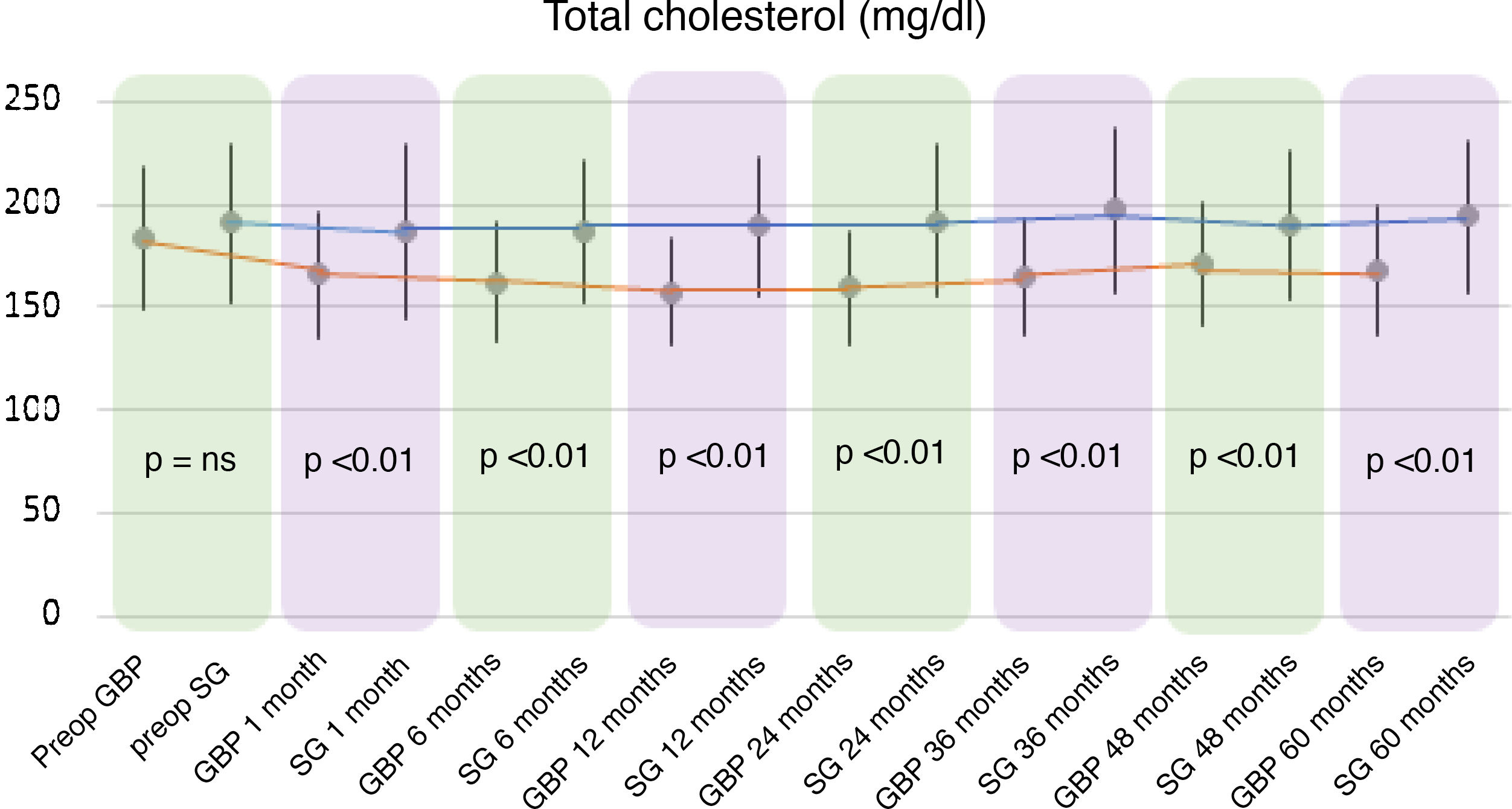

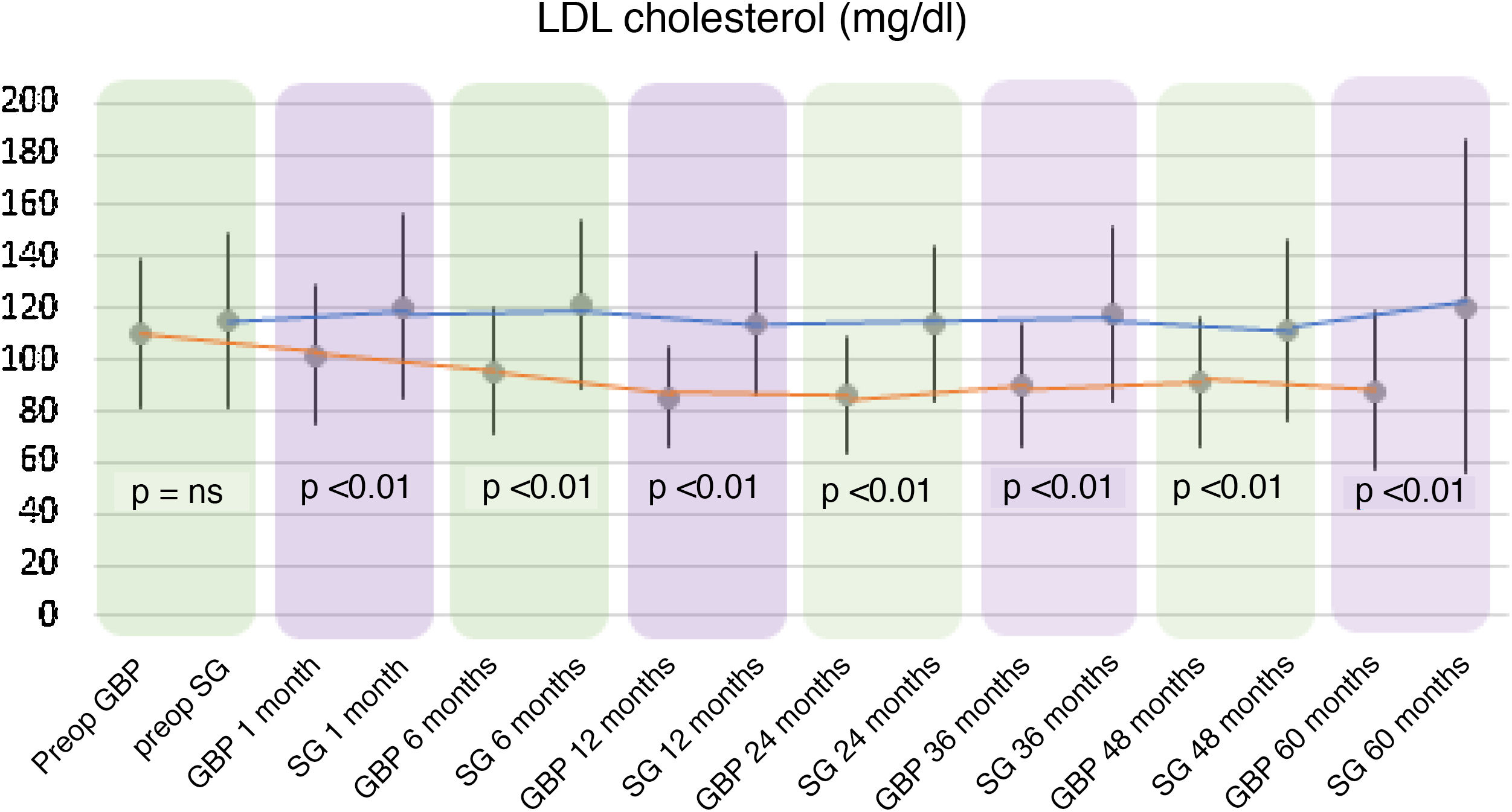

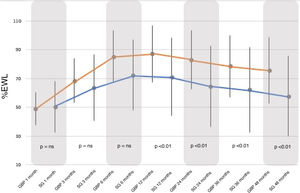

A statistically significant decrease in TC and LDL-cholesterol (LDL) was observed in the GBP group throughout the follow-up. The preoperative mean TC was 182.92 ± 34.7 mg/dl, while the 60-month mean TC was 167.42 ± 31.22 mg/dl (P < .01). The mean preoperative LDL levels were 109.89 ± 28.88 mg/dl, which fell to 88.06 ± 30.74 mg/dl at the end of the follow-up (P < .01). Regarding the SG group, no statistically significant changes were observed in TC or LDL plasma levels.

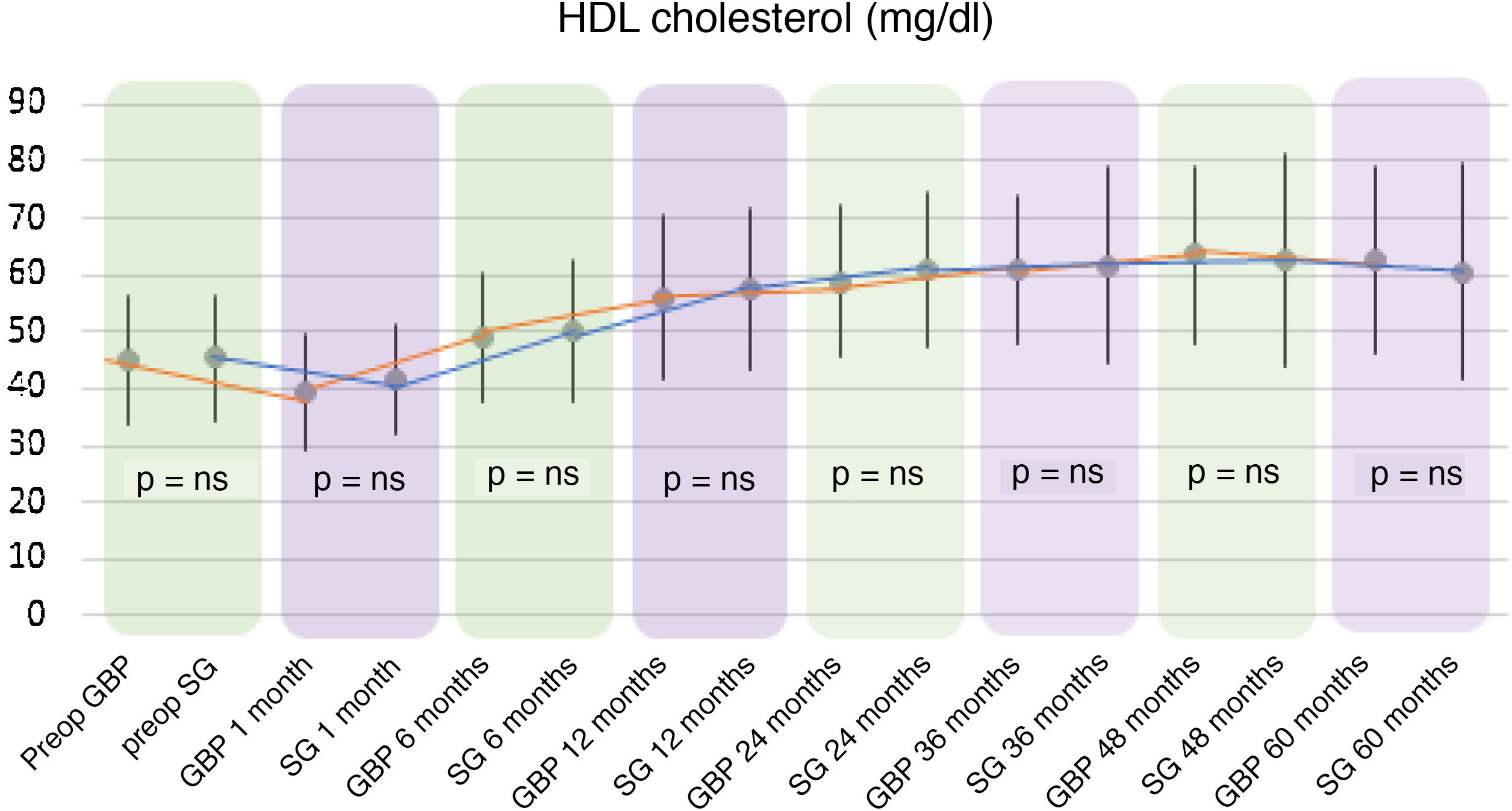

In both the GBP and SG groups, a significant decrease in HDL cholesterol (HDL) was observed after the first month after surgery, followed by an increase up to 60 months. In the GBP group, mean HDL levels improved significantly from 45.13 ± 11.32 mg/dl preoperatively to 62.55 ± 16.16 mg/dl at five years (P < .01). In the SG group, the preoperative mean HDL of 45.46 ± 10.96 mg/dl increased to 60.64 ± 18.73 mg/dl at five years (P < .01).

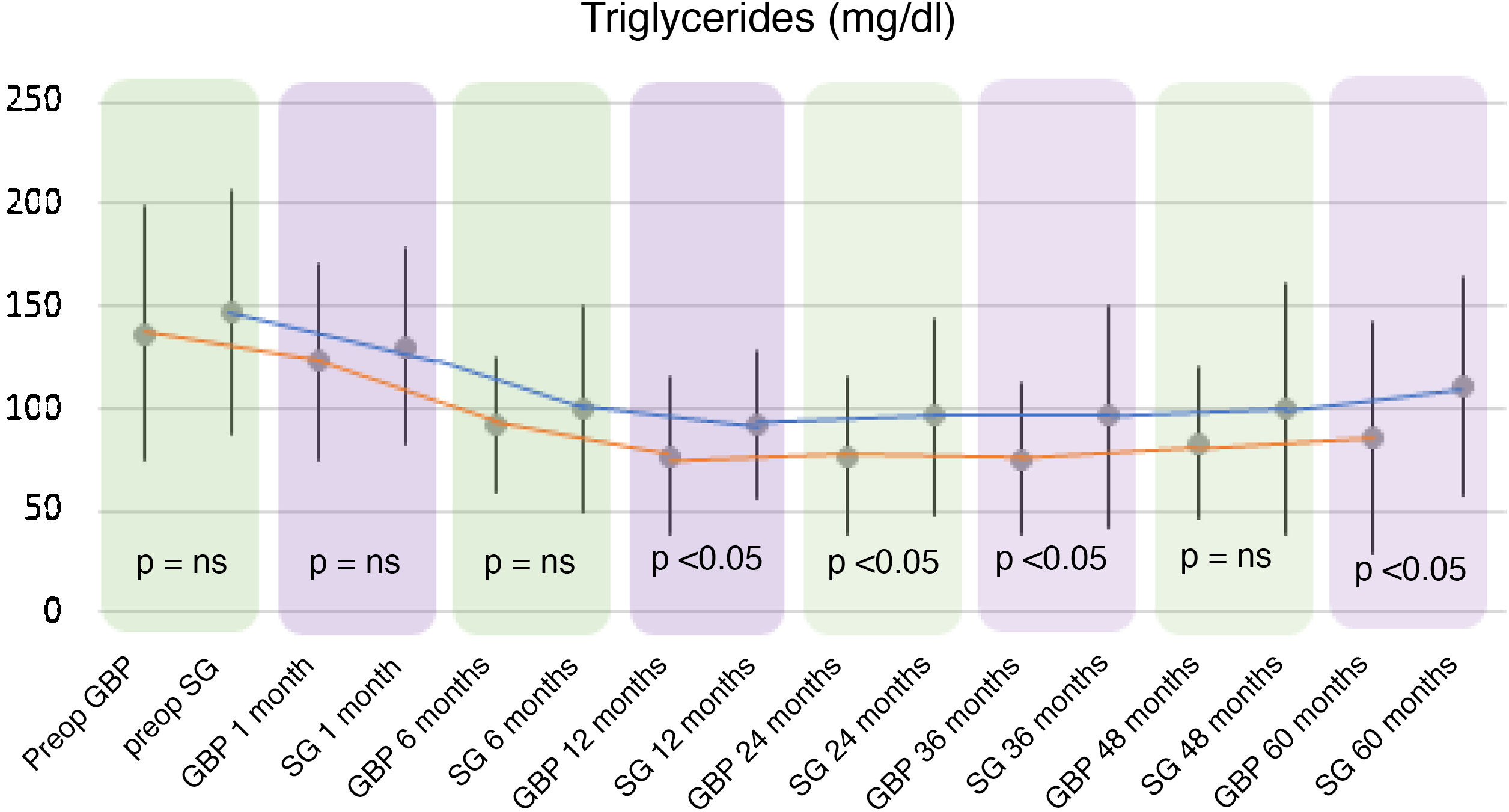

Regarding triglyceride levels, a significant decrease was observed in both groups, reaching a mean of 86.06 ± 56.57 mg/dl (P < .01) in the GBP group at five years (136.86 ± 62.53 mg/dl preoperatively) and 111.08 ± 53.08 mg/dl (P < .01) in the SG group (147.96 ± 59.87 mg/dl preoperatively).

When comparing both techniques, the GBP group was found to have statistically superior results to the SG group in the improvement of TC and LDL-cholesterol levels throughout follow-up (P < .01) (Figs. 3 and 4). In contrast, no statistically significant differences were observed in terms of HDL cholesterol improvement between the two groups at any time during follow-up (Fig. 5). Finally, despite the fact that both groups had significantly decreased TG levels, after 12 months the results observed were better in the GBP group compared to the SG group at 12, 24, 36 and 60 months (P < .05) (Fig. 6).

This study compares the two techniques most often used today in bariatric surgery, GBP and sleeve gastrectomy, providing medium-long-term results in terms of weight loss and improvement of the lipid profile. The preoperative characteristics of the two study groups were similar, except for age, with the SG group being older (47.34 ± 10 years) than the GBP group (42.2 ± 10 years).

Weight loss was analysed with each surgical technique and the %EWL was compared. In both procedures, a similar weight evolution trend was observed: an increase in %EWL up to 12 months that remained stable to 24 months and decreased to 60 months. In the review conducted by Karmali et al. in 2013, this decrease in %EWL was attributed to patient-related factors (lack of adherence to diet, physical inactivity, mental and hormonal causes) and surgery-related factors (loss of the restrictive component due to dilation of the reservoir or gastrojejunal anastomosis and therefore loss of early satiety sensation).13

Despite the fact that the evolution in terms of %EWL was similar for both techniques, the GBP group presented a significantly greater increase, achieving excellent results according to the criteria proposed by Baltasar et al.10 compared with the SG group that showed acceptable results at the end of follow-up (75.6% GBP versus 57.8% SG; P < .01). This is consistent with the published findings of the meta-analysis carried out by Li et al.14 in 2015 of several 60-month follow-up studies. In these, the %EWL achieved by GBP ranges from 63% to 76% and that achieved by SG is between 55%–67%.15 Therefore, weight loss is related to the characteristics of each technique, with greater weight loss seen with GBP due to its restrictive component, which reduces intake, associated with the malabsorptive component, which alters the absorption of nutrients in the small intestine.14

Both techniques achieved statistically significant complete remission of DM, with 80% recorded for GBP and 52.4% for SG, with no differences found between both procedures. Ahmed et al.16 published similar results at five years, observing a DM resolution percentage of 88.9% for GBP and 66.7% for SG.

With the GBP technique, 54.8% (P < .001) of patients with preoperative hypercholesterolaemia met complete remission criteria at 60 months, while this decreased to 14.3% (P = ns) in the SG group. Our results are similar to those of Climent et al.,17 who published a retrospective analysis with a 60-month follow-up in which they observed a hypercholesterolaemia resolution percentage of 44.8% (GBP) versus 23.1% (SG). In light of the above, the resolution of hypercholesterolaemia seems to be favoured by the malabsorptive component inherent to GBP and which sleeve gastrectomy lacks.

Regarding the resolution of hypertriglyceridaemia, 80% of patients in the GBP group met remission criteria (P < .01), while this was 54.5% in the SG group (P = ns). No differences were found between the two techniques, and this significance is likely to be influenced by the low number of patients diagnosed with hypertriglyceridaemia preoperatively.

In the GBP group, a decrease was observed in the number of patients who continued to receive pharmacological treatment at the end of follow-up, while the SG group results were less favourable, observing an increase in patients receiving medical treatment for both types of dyslipidaemia. These results may be limited by the great variability between professionals regarding the indication of lipid-lowering drugs in patients undergoing bariatric surgery.

Most publications agree that GBP improves lipid profile in the short term in obese patients compared to sleeve gastrectomy.18–21 Although there are not many studies that measure laboratory parameters in the medium-long term, the results tend to be maintained over time.17 Our study also found that GBP offers a medium-long-term improvement in lipid profile compared to sleeve gastrectomy.

While the TC and LDL-cholesterol levels decreased in the GBP group, their plasma concentrations did not change significantly in the SG group. This greater decrease observed in GBP seems to be associated with the malabsorption generated by the technique.21

Regarding HDL cholesterol, both techniques showed a significant rise from the sixth postoperative month to the end of follow-up, with no differences found when comparing the two procedures. Although there is consensus in published studies regarding a significant increase in HDL both in GBP and in sleeve gastrectomy, there are discrepancies when comparing the results of the two techniques.22

Most studies assert that the two techniques do not differ regarding the increase in HDL cholesterol.18,23,24 This could be due to improved insulin resistance after bariatric surgery.25 On the other hand, some publications assert that restrictive techniques yield a greater increase in HDL cholesterol than malabsorptive techniques, due to the decrease in ghrelin when resecting the gastric fundus. This hormone is involved in the metabolism of HDL due to the presence of certain polymorphisms in its nucleotides, showing an inverse relationship. This fact, together with its effect on carbohydrate metabolism, gastric emptying and appetite, would explain both the reduction in weight, and the resolution of diabetes and increase in HDL cholesterol following sleeve gastrectomy.22,26 However, there is currently great disparity in results regarding ghrelin levels after the two bariatric procedures, since other authors found no differences between the two techniques in terms of the concentration of this hormone.27

TG levels were significantly reduced from six months in GBP and from the first month in sleeve gastrectomy. Even so, no significant differences were found between the two techniques until 12 months, when GBP began to show significantly better results than sleeve gastrectomy. This was maintained until the end of follow-up. These results are in line with the evolution of weight loss, with no differences found between the two techniques before 12 months, but with a greater reduction in BMI seen in GBP than in sleeve gastrectomy from the first year onwards.

Therefore, the improvement in TG levels seems to be related to weight loss after bariatric surgery. By modifying the normal anatomy of the small intestine, promoting malabsorption and achieving better results for weight loss, GBP achieves a greater decrease in TG compared to sleeve gastrectomy.21

LimitationsThere are several limitations to this study, including those inherent to its retrospective design. Data on adherence to diet were not collected postoperatively and in the long term, and physical activity carried out before and after surgery was also not evaluated. Finally, there are no defined criteria regarding the medical indication for lipid-lowering treatment in patients who have had bariatric surgery, so this great variability in its prescribing constitutes another limitation of our study.

ConclusionsGBP obtained better results in terms of weight loss, resolution of hypercholesterolaemia and decreased plasma TG levels when compared with SG in the medium-long term. Therefore, GBP appears to be a more appropriate technique for obese patients with preoperative hypercholesterolaemia.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Abellán Garay L, Navarro García MI, González-Costea Martínez R, Torregrosa Pérez NM, Vázquez Rojas JL. Evaluación del perfil lipídico a medio-largo plazo después de cirugía bariátrica (bypass gástrico versus gastrectomía vertical). Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:372–380.