Type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM-1) is one of the most common chronic childhood diseases, and it is essential to optimize glycemic control in order to avoid complications. For years, interstitial glucose measurement systems (MGI systems) have been among the new technologies at the forefront of self-care.

ObjectivesTo determine the impact on the well-being of the caregivers of patients with DM-1 under 18 years of age, controlled at a Pediatric Diabetes Unit of a third level hospital, of the use of MGI systems.

Material and methodsThis was an observational, descriptive and analytical cohort study based on a questionnaire completed by the patients’ caregivers, as well as from the patient's clinical history.

ResultsThere were 120 participants (55.5% males), with a mean age 13.20 +/- 3.71 years and mean glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) 7.36% +/- 0.90. 52.5% of the sample used MGI systems. The caregivers of patients using MGI systems showed significantly higher scores (p < 0.05) regarding well-being, compared to the caregivers of patients not using this technology. In the former, a significant improvement (p < 0.05) in these variables with respect to the values prior to the beginning of their use was observed.

ConclusionsThe use of MGI systems for diabetes self-management in our study led to a greater sense of well-being on the part of caregivers compared with before their introduction, as well as in comparison with those who continued to perform measurements using daily capillary glycemias.

La diabetes mellitus tipo 1 (DM-1) es una de las enfermedades crónicas más frecuentes de la infancia, siendo fundamental optimizar el control glucémico para evitar complicaciones. Disponemos hace años, de nuevas tecnologías en la vanguardia del autocuidado, los sistemas de medición de glucosa intersticial (sistemas MGI), siendo imperativo para el clínico considerar el impacto medido no solo en resultados clínicos.

ObjetivosDeterminar el impacto en la esfera bienestar de cuidadores de pacientes con DM-1, menores de 18 años, controlados en una Unidad de Diabetes Pediátrica de un hospital de tercer nivel, relacionado con la utilización de sistemas MGI.

Material y métodosEstudio de cohorte observacional, descriptivo y analítico cuyas variables proceden de un cuestionario completado por los cuidadores de los pacientes, así como de la historia clínica del paciente, tras consentimiento y aprobación del Comité de Ética.

ResultadosCiento veinte participantes (55,5% varones), con edad media 13,20+/-3,71 años y hemoglobina glicosilada (HbA1c) media 7,36%+/-0,90. El 52,5% de la muestra utiliza sistemas MGI. Los cuidadores de pacientes usuarios de sistemas MGI muestran puntuaciones significativamente mayores (p < 0,05) en las variables de la esfera de bienestar, frente a los cuidadores de pacientes no usuarios de dicha tecnología. En cuidadores de pacientes que utilizan sistemas MGI, se objetiva una mejoría significativa (p < 0,05) en dichas variables con respecto a los valores previos al inicio de su utilización.

ConclusionesLa utilización de sistemas MGI para el autocontrol de la diabetes en nuestro estudio, logra una mayor sensación de bienestar percibido por los cuidadores tras el inicio de su utilización, así como en comparación con aquellos que realizan mediciones mediante glucemias capilares diarias.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM1) is one of the most common chronic diseases of childhood, with only a quarter of cases being diagnosed in adulthood.1 The incidence throughout the world is heterogeneous, varying according to geographic location, age, gender, family history and ethnicity, with estimates from 0.1 to 65 per 100,000 children under 15 years of age.1

The complexity in the management of this disease lies in the great importance of self-care, which is vital for preventing medium- and long-term complications.2 Optimal control of blood glucose depends on both adequate adjustment of insulin doses and frequent monitoring of glucose levels. Frequent monitoring enables patients and their caregivers to become familiar with their blood glucose response to different types and amounts of food, exercise and stress levels.3 It also improves blood glucose control in children4–6 and reduces the frequency of severe hypoglycaemic episodes,7 as it can often be difficult to detect extreme blood glucose levels based solely on symptoms. There is a large stress component associated with the complexities of managing DM1 in patients’ families.

There have been numerous advances in the management of DM1 in recent years, with increasingly sophisticated new technologies available to provide state-of-the-art care,4 and approved for use in paediatric patients. As a result, the options for glucose monitoring now include multiple daily capillary blood glucose levels and using one of the interstitial glucose monitoring (IGM) systems.3 These devices allow users to obtain interstitial fluid glucose readings in real time and/or intermittently or retrospectively, and they also provide information on the direction and speed of blood glucose changes.8,9 In motivated patients who use them frequently, these devices have been shown to reduce the level of glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), in both adults and children and adolescents alike.3,10–13 The practical utility of IGM is increasing at a frenetic pace with the introduction of updates and improvements, including new applications adaptable to mobile phone systems. With such developments, clinicians urgently need to examine the user experience, in order for any problems to be detected and to set out objectives for achieving their sustained use.8 The impact of these technologies, measured in psychosocial outcomes in children and their caregivers, remains subject to debate and, generally speaking, the psychosocial aspect tends only to be included among secondary outcomes in studies involving IGM systems.14–17

The aim of this study was to determine the perceived impact of the use of IGM systems on the physical and emotional sphere of caregivers of patients under 18 years of age with DM1 under follow-up in the Paediatric Diabetes Unit of a tertiary hospital.

Patients and methodsDesign and type of study. Data collectionObservational, descriptive, analytical cohort study. A questionnaire was designed and sent by email to the parents and/or legal guardians of the patients after they had agreed to take part in the study. The data were collected prospectively and the results were subsequently completed with clinical data after retrospective review of the patient’s medical records. The study was conducted after evaluation and approval by the corresponding Independent Ethics Committee.

Study scope. Reference population. Sample selection. Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe reference population is made up of patients with DM1 under follow-up at the Paediatric Diabetes Unit of a tertiary hospital. The study sample came from the reference population described and included patients whose parents and/or legal guardians agreed to take part in the research. The exclusion criterion was not agreeing to take part in the study.

Variables recordedA questionnaire was designed to be completed by the parents and/or legal guardians of the patients (main caregiver). The survey included the following items relating to the feeling of physical and emotional well-being: perception of health; feeling of stress; fatigue; perceived physical and mental state; feeling of mental agility; perception of adequate hours of sleep; feeling of quality of sleep; their own happiness; and perceived degree of patient happiness. The respondent caregiver was asked to rate each item from 1 to 7, with 7 representing the best rating. From the caregivers of patients who used IGM systems, we collected data on their assessment of the situation prior to the use of the meter and their assessment after using it for at least six months. Reviewing the patient's medical records provided us with their personal details (age, gender), age at onset, time since onset of the disease, mean HbA1c over the previous year, type of treatment and type of IGM system. It should be noted that at the time the study was carried out, the families of the patients had decided to pay for the system themselves, as at that point it was not funded by Community Health in paediatric patients.

Statistical analysisA database was created with the SPSS version 23 software. We used descriptive statistics for variables and comparative means of the sample, organising, presenting and synthesising the data using measures of central tendency (mean) and dispersion (SD or range). Additionally, analytical statistics were performed and parametric tests such as Student’s t test were used to compare means. The significance threshold adopted for all tests was p < 0.05 (95% CI). As it was a survey study comparing two groups, the data were weighted in order to improve the representativeness of the sample. The score obtained in the scale's items on perceived well-being prior to the patient’s onset of diabetes was used as a covariate in the analysis.

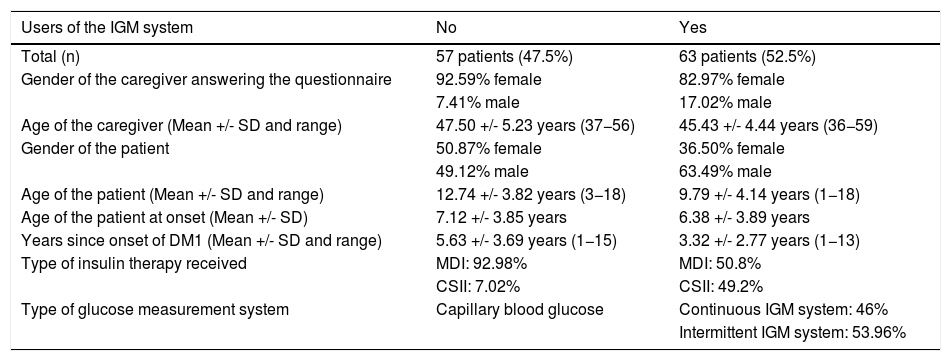

ResultsOut of the total reference population, results were obtained from a total of 120 participants, with an acceptance rate to participate in the study of 80.5%. The actual mean age of the sample was 13.20 +/- 3.71 years, with a mean age at the onset of the disease of 6.73 +/- 3.88 years (range 1–15) and a mean time since onset of the disease of 6.47 +/- 3.75 years, with a slight predominance of males (55.5%). The mean HbA1c of the total sample was 7.36% +/- 0.90. Regarding the type of treatment, 70.8% were receiving intensive therapy with multiple daily doses of insulin (MDI) and 29.2% by continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII). In total, 52.5% of the patients had been using some type of IGM system (continuous or flash) for anywhere from six months to three years. 48% of patients treated with MDI and 89% with CSII used an IGM system, with 94% of these using IGM on a daily basis. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample according to the group to which they belonged, i.e. non-users of an IGM system or users of an IGM system, along with the demographic data of the caregivers in each group (Table 1). In terms of the distribution of the two groups, statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were only detected in the actual age of the patient and years since onset of the disease, with the group of patients using IGM systems found to be younger and to have less time since DM1 onset.

Characteristics of the sample according to group: non-users of the IGM system versus users of the IGM system.

| Users of the IGM system | No | Yes |

|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | 57 patients (47.5%) | 63 patients (52.5%) |

| Gender of the caregiver answering the questionnaire | 92.59% female | 82.97% female |

| 7.41% male | 17.02% male | |

| Age of the caregiver (Mean +/- SD and range) | 47.50 +/- 5.23 years (37−56) | 45.43 +/- 4.44 years (36−59) |

| Gender of the patient | 50.87% female | 36.50% female |

| 49.12% male | 63.49% male | |

| Age of the patient (Mean +/- SD and range) | 12.74 +/- 3.82 years (3−18) | 9.79 +/- 4.14 years (1−18) |

| Age of the patient at onset (Mean +/- SD) | 7.12 +/- 3.85 years | 6.38 +/- 3.89 years |

| Years since onset of DM1 (Mean +/- SD and range) | 5.63 +/- 3.69 years (1−15) | 3.32 +/- 2.77 years (1−13) |

| Type of insulin therapy received | MDI: 92.98% | MDI: 50.8% |

| CSII: 7.02% | CSII: 49.2% | |

| Type of glucose measurement system | Capillary blood glucose | Continuous IGM system: 46% |

| Intermittent IGM system: 53.96% |

The results are expressed by absolute values (percentages) or mean score +/- standard deviation and ranges.

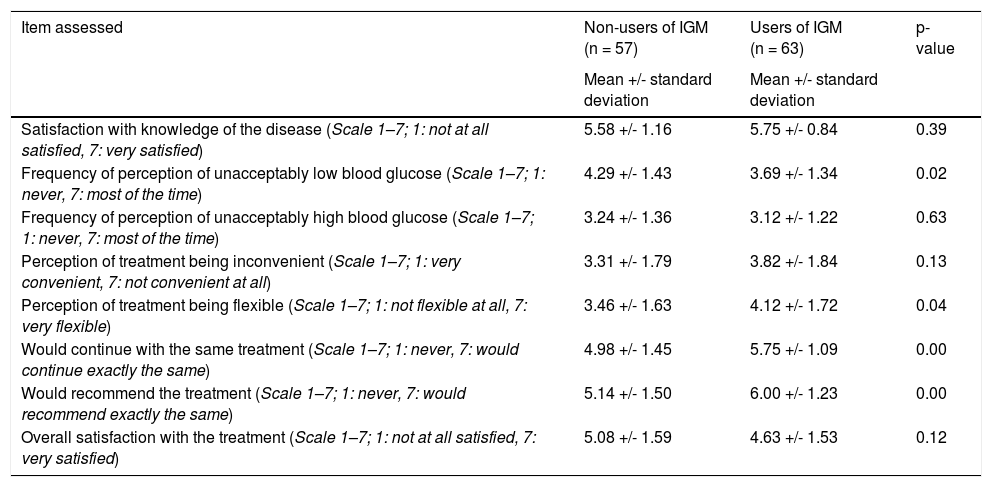

In the questionnaire given to the patient’s main caregiver, the variables collected in the items in the first part related to the caregiver’s perception of how well controlled the patient’s blood glucose was, knowledge of the disease and satisfaction with the treatment received for DM1. Table 2 shows the results obtained from caregivers of patients using IGM systems and those not using IGM systems in separate columns (Table 2).

Level of perception of the main caregivers of patients with diabetes in the study of the management and treatment of the disease, according to the glucose measurement system used in self-monitoring.

| Item assessed | Non-users of IGM (n = 57) | Users of IGM (n = 63) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean +/- standard deviation | Mean +/- standard deviation | ||

| Satisfaction with knowledge of the disease (Scale 1–7; 1: not at all satisfied, 7: very satisfied) | 5.58 +/- 1.16 | 5.75 +/- 0.84 | 0.39 |

| Frequency of perception of unacceptably low blood glucose (Scale 1–7; 1: never, 7: most of the time) | 4.29 +/- 1.43 | 3.69 +/- 1.34 | 0.02 |

| Frequency of perception of unacceptably high blood glucose (Scale 1–7; 1: never, 7: most of the time) | 3.24 +/- 1.36 | 3.12 +/- 1.22 | 0.63 |

| Perception of treatment being inconvenient (Scale 1–7; 1: very convenient, 7: not convenient at all) | 3.31 +/- 1.79 | 3.82 +/- 1.84 | 0.13 |

| Perception of treatment being flexible (Scale 1–7; 1: not flexible at all, 7: very flexible) | 3.46 +/- 1.63 | 4.12 +/- 1.72 | 0.04 |

| Would continue with the same treatment (Scale 1–7; 1: never, 7: would continue exactly the same) | 4.98 +/- 1.45 | 5.75 +/- 1.09 | 0.00 |

| Would recommend the treatment (Scale 1–7; 1: never, 7: would recommend exactly the same) | 5.14 +/- 1.50 | 6.00 +/- 1.23 | 0.00 |

| Overall satisfaction with the treatment (Scale 1–7; 1: not at all satisfied, 7: very satisfied) | 5.08 +/- 1.59 | 4.63 +/- 1.53 | 0.12 |

The results are expressed by the mean score +/- the standard deviation.

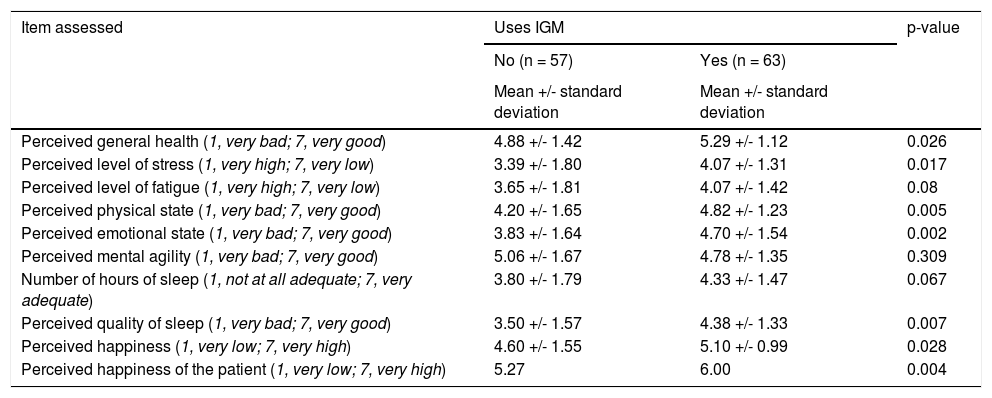

The second part of the questionnaire included aspects related to the feeling of well-being in the psychosocial sphere perceived by the patient’s main caregiver. The results of the statistical analysis (using as a covariate the perception scores for the same items prior to the onset of the patient's diabetes) show better scores in all aspects for the caregivers of patients who were using IGM systems, with significant differences (p < 0.05) in seven of the ten items assessed (Table 3).

Perception of the well-being variables of the main caregivers of patients with diabetes in the study, according to the glucose measurement system used in self-monitoring.

| Item assessed | Uses IGM | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 57) | Yes (n = 63) | ||

| Mean +/- standard deviation | Mean +/- standard deviation | ||

| Perceived general health (1, very bad; 7, very good) | 4.88 +/- 1.42 | 5.29 +/- 1.12 | 0.026 |

| Perceived level of stress (1, very high; 7, very low) | 3.39 +/- 1.80 | 4.07 +/- 1.31 | 0.017 |

| Perceived level of fatigue (1, very high; 7, very low) | 3.65 +/- 1.81 | 4.07 +/- 1.42 | 0.08 |

| Perceived physical state (1, very bad; 7, very good) | 4.20 +/- 1.65 | 4.82 +/- 1.23 | 0.005 |

| Perceived emotional state (1, very bad; 7, very good) | 3.83 +/- 1.64 | 4.70 +/- 1.54 | 0.002 |

| Perceived mental agility (1, very bad; 7, very good) | 5.06 +/- 1.67 | 4.78 +/- 1.35 | 0.309 |

| Number of hours of sleep (1, not at all adequate; 7, very adequate) | 3.80 +/- 1.79 | 4.33 +/- 1.47 | 0.067 |

| Perceived quality of sleep (1, very bad; 7, very good) | 3.50 +/- 1.57 | 4.38 +/- 1.33 | 0.007 |

| Perceived happiness (1, very low; 7, very high) | 4.60 +/- 1.55 | 5.10 +/- 0.99 | 0.028 |

| Perceived happiness of the patient (1, very low; 7, very high) | 5.27 | 6.00 | 0.004 |

The results are expressed by the mean score +/- the standard deviation.

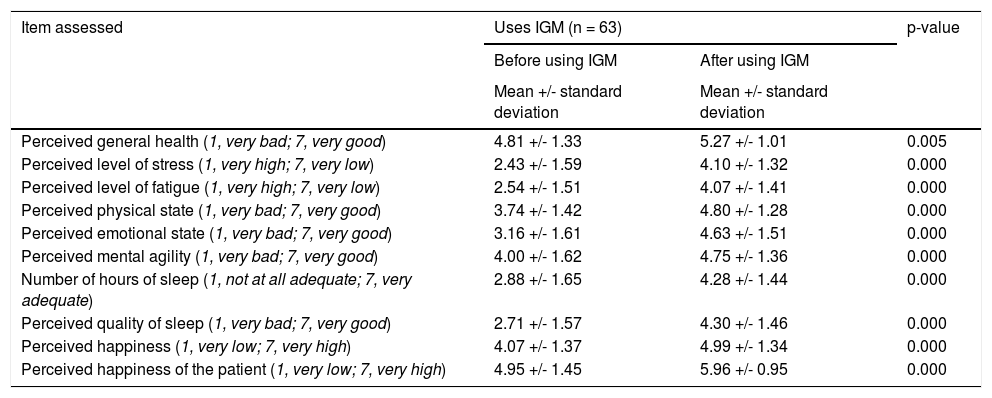

Last of all, we compared the scores of the caregivers of patients using IGM systems after onset of the disease on the well-being scale before and after starting to use these systems. In this case, statistically significant differences were observed, with a significance level of p < 0.01 in all items, with better scores after starting to use these devices (Table 4).

Perception of the well-being variables of the main caregivers of patients with diabetes in the study, before and after starting to use the interstitial glucose measurement system for self-monitoring.

| Item assessed | Uses IGM (n = 63) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before using IGM | After using IGM | ||

| Mean +/- standard deviation | Mean +/- standard deviation | ||

| Perceived general health (1, very bad; 7, very good) | 4.81 +/- 1.33 | 5.27 +/- 1.01 | 0.005 |

| Perceived level of stress (1, very high; 7, very low) | 2.43 +/- 1.59 | 4.10 +/- 1.32 | 0.000 |

| Perceived level of fatigue (1, very high; 7, very low) | 2.54 +/- 1.51 | 4.07 +/- 1.41 | 0.000 |

| Perceived physical state (1, very bad; 7, very good) | 3.74 +/- 1.42 | 4.80 +/- 1.28 | 0.000 |

| Perceived emotional state (1, very bad; 7, very good) | 3.16 +/- 1.61 | 4.63 +/- 1.51 | 0.000 |

| Perceived mental agility (1, very bad; 7, very good) | 4.00 +/- 1.62 | 4.75 +/- 1.36 | 0.000 |

| Number of hours of sleep (1, not at all adequate; 7, very adequate) | 2.88 +/- 1.65 | 4.28 +/- 1.44 | 0.000 |

| Perceived quality of sleep (1, very bad; 7, very good) | 2.71 +/- 1.57 | 4.30 +/- 1.46 | 0.000 |

| Perceived happiness (1, very low; 7, very high) | 4.07 +/- 1.37 | 4.99 +/- 1.34 | 0.000 |

| Perceived happiness of the patient (1, very low; 7, very high) | 4.95 +/- 1.45 | 5.96 +/- 0.95 | 0.000 |

The results are expressed by the mean score +/- the standard deviation.

It should be noted that 49% of the patients who were not using the IGM system at the time of the study had used it in the past for at least six months (but had not used it for at least one year prior to the study). The reasons given by the caregivers for why they no longer used it were: its high cost in 70%; that the patients themselves had rejected it in 40%; and in 36%, that they did not feel safe with the measurement the system showed.

DiscussionDespite the great advances in understanding and management of DM1, achieving adequate blood glucose control in children and adolescents continues to be a great challenge. This causes a degree of psychological stress in the caregivers of these patients trying to achieve better control of the disease in their children, and can affect the quality of life of the whole family.18 The relatively recent availability of IGM systems in the paediatric population is a promising development, allowing patients to be monitored remotely by their caregivers.19 However, to date, few published studies have investigated the experience of caregivers with the use of these systems. The studies that are available suggest that the use of IGM systems may help improve the psychosocial well-being of these caregivers, especially in the case of patients who are dependent on their care.19,20 We therefore conducted our study to obtain a better understanding of the experiences of parents of children with DM1 with the use of this technology, investigating certain factors like satisfaction with their knowledge about the disease and the way it was being managed and treated, but essentially factors in the sphere of psychosocial well-being.

We had a good response rate to take part and were able to include a large percentage of patients belonging to the reference population in the study. In terms of the characteristics of our sample, in line with the available evidence, we found no clear predominance of gender, despite diabetes being an autoimmune disease and the fact that this type of disorder is more commonly associated with females.1,18 The mean age at onset of the disease had a very broad range, in line with the literature, where DM1 is described as commonly having two incidence peaks, from the age of 4–6 years and from 10 to 14 years,19–21 with the mean age at onset below the age of 10; it has been reported that approximately half of children with DM1 present with the disease before that age.22 Analysing differences in our two groups (users of the IGM system and non-users), we only found that the group using the new technology was significantly younger and so had a shorter time since disease onset. This is probably due to the fact that younger patients are more dependent on self-management of their DM1. In addition, less time since disease onset may mean it was easier for the caregivers to adapt to a new measurement system, as they had been using daily capillary blood glucose for a shorter period. However, more research and more comparative studies would be necessary to understand these differences.

Overall, our results suggest that the IGM systems have a positive influence on the management of the disease. In the first part of the questionnaire, which refers to knowledge about the disease and factors related to management and satisfaction with the treatment received, more positive scores were obtained in the group of caregivers of patients using IGM systems in six of the eight items assessed, with significant differences found in both groups in half of these. This group of caregivers was more satisfied with their knowledge about the disease, with a lower rate of perception of unacceptably high blood glucose and a significantly lower perception of unacceptably low blood glucose. In addition, they perceived the treatment to be somewhat more inconvenient, but significantly more flexible. Lastly, on whether they would like the patient to continue with the same treatment and whether they would recommend it to other people, the scores were significantly higher for caregivers of patients using IGM systems.

Meanwhile, the results obtained in the psychosocial sphere in relation to the feeling of well-being perceived by the patient’s main caregiver showed more positive values among caregivers of IGM system users in nine out of the ten items, with the results being significant in seven of these. They had a higher perceived level of health in general, including both physical and emotional state, with a lower level of stress. In addition, they had a significantly better perception in terms of quality sleep, considering the number of hours of sleep, similar to the caregivers of patients who did not use these systems, at a medium level on the scoring scale. They also had a higher level of perceived happiness both for themselves and the patient. The only item that the caregivers of patients using IGM systems rated worse, although not significantly, was the feeling of mental agility.

Last of all, we analysed the differences in the previously mentioned aspects on the well-being scale in the caregivers of patients using IGM systems after onset of the disease, before and after starting to use these systems. The results suggest that use of the IGM systems improves the overall well-being perceived by the families.

Our results are consistent with those obtained in the other studies published to date.9,19,21,22 The positive aspects of the use of this technology most emphasised by the parents of the patients in previous studies are the positive influence on sleep,9,19,20 plus peace of mind and calmness, as they feel less anxious and safer,19,23–26 along with a greater sense of freedom, as they are able to participate in activities that were previously restricted.19 One of the factors that most influenced this situation was the fear of hypoglycaemia, particularly during sleep, considered one of the greatest worries among parents of patients with DM1.27 The possibility of receiving alerts should hypoglycaemic events occur makes it easier to have a more comfortable night’s sleep for most of the parents,19,20 affecting their physical and emotional state. However, one study reported that some parents feel that their sleep is more interrupted by these alarms and so consider it a handicap.28

Therefore, despite the positive results and the potential of these systems highlighted by the evidence available to date, there are still certain situations that both patients and caregivers do not consider optimal.2,29

One of the main barriers considered in the studies and reported most frequently by the caregivers in our sample who used this type of measurement and ended up abandoning it, is financial.8,24,30 Cost is one of the most negative aspects reported in terms of the use of these systems in various studies published to date. The adult population that uses these systems expresses concern about maintaining its use over time, with the resulting financial burden, while adolescents are worried about losing such an expensive device.

However, another important barrier which is reflected in the available evidence and was the second most common cause of abandoning the system in our study, is rejection by the patient. Patients and their parents are frustrated by the multiple skin problems the sensor causes (irritation, pain, etc.). Other reasons for rejection by the patient may be due to the greater visibility of the diabetes for others because the sensor can be difficult to hide,8,24,30 plus, especially in adolescents, the fact of feeling “spied on” or feeling that their privacy is being violated by receiving so much data day after day.

Finally, we have to take into account that perceptions by caregivers can be influenced by the level of trust in and adherence to new technologies, which can depend on a range of different biopsychosocial factors in each family group.

Our study has a series of limitations in terms of applying the conclusions generally to the entire population of people with diabetes. On the one hand, there may be a selection bias, as agreeing to participate in the study may be related to greater motivation in the management and self-control of the disease. On the other, in our population, at the time of the study, the families of the patients had to pay for the IGM systems as they were not included in the Portfolio of Community Health Services. That may have affected the representativeness of the sample, as not all families would have been able to afford it. Nevertheless, more than half of our sample did have these systems, with most of the patients using them on a daily basis, and their use was significantly higher in patients who wear an insulin pump with CSII.

Lastly, we should state that in our study population we analysed the influence of the use of IGM systems versus their non-use in the management of DM1, without distinguishing between the type of measurement system used (continuous or intermittent) or the type of insulin administration (MDI and CSII). We also need to clarify that the questionnaire used in our study was not validated as, at the time we were using it, there were no validated questionnaires in this area. That obviously makes it more difficult to draw a comparison with other studies. For that and the other reasons mentioned previously, we consider that more research is necessary with a larger sample size, distinction between types of sensors and method of insulin therapy used, as well as the design and use of validated questionnaires. Also necessary are the inclusion of different socioeconomic groups and not only those able to pay for the system, and the conduct of longer-term studies.

Our results, in conjunction with those of other studies published to date, lead us to the conclusion that, if we are to break down the current barriers associated with the use of IGM systems, further studies are needed with larger samples in order to continue to improve our knowledge about these systems and their effect on quality of life and well-being in patients with diabetes and their caregivers.

Authorship/collaboratorsSara María Barbed Ferrández: data collection, review of medical records, responsibility for informed consent, explanation of the study to patients, writing of the manuscript.

Teresa Montaner Gutiérrez: design of the survey and database. Statistical analysis.

Gemma Larramona Ballarín: design of the survey and database. Statistical analysis.

Marta Ferrer Lozano: writing and revision of the manuscript.

Gracia María Lou Francés: writing and revision of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Barbed Ferrández SM, Montaner Gutiérrez T, Larramona Ballarín G, Ferrer Lozano M, Lou Francés GM. Impacto en el bienestar percibido por cuidadores de niños y adolescentes con diabetes tipo 1 mediante la utilización de sistemas de medición de glucosa intersticial. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:243–250.