To provide practical recommendations to assess and treat osteoporosis in males.

ParticipantsMembers of the Bone Metabolism Working Group of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology.

MethodsRecommendations were formulated using the GRADE system (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) to describe both the strength of recommendations and the quality of evidence. A systematic search was made in Medline (PubMed) using the following associated terms: “osteoporosis”, “men”, “fractures”, “bone mineral density”, “treatment”, “hypogonadism”, and “prostate cancer”. Papers in English and Spanish with publication date before 30 August 2017 were included. Current evidence for each disease was reviewed by 2 group members. Finally, recommendations were discussed in a meeting of the working group.

ConclusionsThe document provides evidence-based practical recommendations for diagnosis, assessment, and management of osteoporosis in men and special situations such as hypogonadism and prostate cancer.

Proporcionar unas recomendaciones prácticas para la evaluación y tratamiento de la osteoporosis del varón.

ParticipantesMiembros del Grupo de Metabolismo Mineral de la Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición.

MétodosLas recomendaciones se formularon de acuerdo con el sistema Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) para establecer tanto la fuerza de las recomendaciones como el grado de evidencia. Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática en Medline de la evidencia disponible sobre la osteoporosis del varón usando las siguientes palabras claves asociadas: osteoporosis, men, fractures, bone mineral density, treatment, hypogonadism y prostate cancer. Se revisaron artículos escritos en inglés y español con fecha de inclusión hasta el 30 de agosto del 2017; cada tema fue revisado por 2personas del grupo. Tras la formulación de las recomendaciones, estas se discutieron en una reunión conjunta del grupo de trabajo.

ConclusionesEl documento establece unas recomendaciones prácticas basadas en la evidencia acerca del diagnóstico, evaluación y tratamiento de la osteoporosis del varón y situaciones especiales como el hipogonadismo y el tratamiento con terapia de déficit androgénico en el carcinoma de próstata.

Osteoporosis is defined as a systemic skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mass and impaired bone microarchitecture, with a resultant increase in bone fragility and a greater susceptibility to fractures.1,2 The densitometric definition of osteoporosis of the World Health Organization also applies to males.3,4

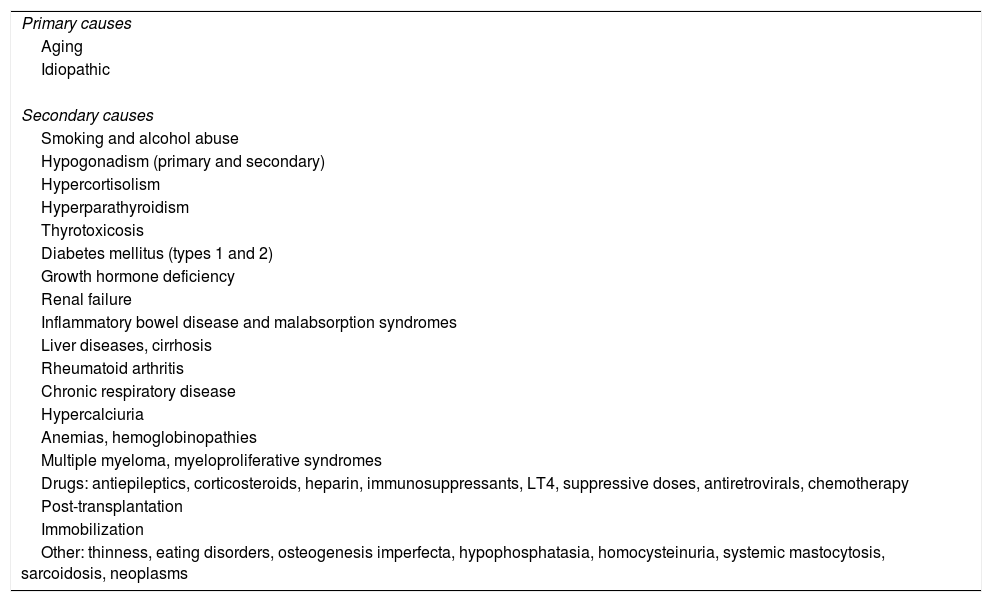

Male osteoporosis is a condition with a high prevalence of secondary osteoporosis (40–60% in males aged less than 70 years) (Table 1).2,4,5 In Spain, the estimated prevalence rates of osteoporosis in males are 8.1% and 11.3% in those older than 50 and 70 years respectively.2,6 Osteoporotic fractures in males are characterized by greater morbidity and mortality as compared to females.6,7

Causes of osteoporosis in males.

| Primary causes |

| Aging |

| Idiopathic |

| Secondary causes |

| Smoking and alcohol abuse |

| Hypogonadism (primary and secondary) |

| Hypercortisolism |

| Hyperparathyroidism |

| Thyrotoxicosis |

| Diabetes mellitus (types 1 and 2) |

| Growth hormone deficiency |

| Renal failure |

| Inflammatory bowel disease and malabsorption syndromes |

| Liver diseases, cirrhosis |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Chronic respiratory disease |

| Hypercalciuria |

| Anemias, hemoglobinopathies |

| Multiple myeloma, myeloproliferative syndromes |

| Drugs: antiepileptics, corticosteroids, heparin, immunosuppressants, LT4, suppressive doses, antiretrovirals, chemotherapy |

| Post-transplantation |

| Immobilization |

| Other: thinness, eating disorders, osteogenesis imperfecta, hypophosphatasia, homocysteinuria, systemic mastocytosis, sarcoidosis, neoplasms |

The recommendations were formulated according to the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system.8 In terms of the strength of the recommendation, a distinction is made between strong recommendations, expressed as “We recommend” and number 1, and weak recommendations, expressed as “We suggest” and number 2. The quality of evidence is expressed using symbols: ⊕, indicates very low evidence; ⊕⊕, low evidence; ⊕⊕⊕, moderate evidence; and ⊕⊕⊕⊕, high evidence.8 A systematic search was made in Medline for the evidence available regarding osteoporosis in males and the title of each chapter. Articles written in English and Spanish published up to August 30, 2017 were reviewed. Each topic was reviewed by two members of the group. Once the recommendations had been formulated, they were discussed at a joint meeting of the Working Group.

EvaluationPhysical examination and laboratory testsRecommendation- -

We recommend that an accurate clinical history be taken and a detailed physical examination be conducted. Relevant data include drugs used, chronic diseases, alcohol consumption, smoking, any history of falls or fractures in adult age, and any family history of osteoporosis or hip fracture in first-degree relatives. Physical examination should include patient height, a comparison with his maximum height and dorsal kyphosis and the body mass index. Signs suggesting secondary causes should be assessed. An evaluation of balance, gait, and fragility should be made if there is a history of falls. A dental examination is suggested when treatment with bisphosphonates is under consideration (1⊕⊕OO).

- -

We recommend that the following basic laboratory tests be carried out in the initial evaluation: calcium, phosphorus and alkaline phosphatase levels, kidney and liver function tests, a complete blood count, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, total testosterone, TSH, and calcium levels, creatinine in 24-h urine, and the urinary calcium/creatinine ratio (1⊕⊕OO).

- -

We recommend that additional laboratory tests such as free or bioavailable testosterone, urinary free cortisol, a thyroid profile, intact PTH, protein electrophoresis in blood and urine, tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies or any other test deemed appropriate in the clinical context be carried out (1⊕⊕OO).

- -

We do not suggest the routine measurement of bone remodeling markers (BRMs) (2⊕OOO).

The clinical history and a physical examination allow for the identification of any risk factors and for a diagnosis of secondary causes.5,9,10 As regards BRMs, their capacity for predicting accelerated bone loss or fracture in the clinical management of osteoporosis in males has not been clearly established.4,11

Densitometry and other tools to diagnose osteoporosis in malesRecommendation- -

We recommend the measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in males at a significant risk of osteoporosis (1⊕OOO).

- -

We suggest the use of the database based on young females from the NHANES III study, at least in the femur, and local data bases for Z-score calculation only (2⊕OOO).

- -

We suggest the use of systems for vertebral fracture detection based on DXA in males over 80 years of age, in those aged 70–79 years with additional risk factors or if there is a height loss greater than 6cm and, if available, the trabecular bone score to improve FRAX accuracy (2⊕OOO).

As in females, diagnosis is traditionally based on the measurement by DXA of apparent BMD as compared to a reference population of young Caucasian US women from the NHANES III study, according to the definitions and recommendations of national and international bodies.1–4 The World Health Organization and the International Society for Clinical Densitometry recommend that the definition of osteoporosis based on the T-score (<−2.5) for people over 50 years of age should be the same for both sexes (the number of standard deviations [SD] of the patient from the mean in young, healthy, Caucasian women from the NHANES III study).4 In people younger than 50 years of age, the use of the Z-score (number of SDs as compared to a population of the same age and sex) and clinical criteria (basically prevalent fracture) is recommended.2–5

The spine and hip are the recommended areas for measurement, but may be replaced by the forearm when those areas are not assessable, in the event of hyperparathyroidism or androgen deficiency therapy, and in very obese subjects.2,4

A trabecular bone score obtained from DXA should not be used as the only diagnostic element or therapeutic indication, but it may improve FRAX accuracy.4

Indication of screening to rule out osteoporosis in malesRecommendation- -

We suggest an evaluation of males over 70 years of age to rule out osteoporosis (2⊕⊕OO).

- -

We suggest an evaluation to rule out osteoporosis in males under 70 years of age if they have additional risk factors for osteoporosis or non-traumatic fracture (2⊕⊕OO).

An age of 70 years is a sufficient risk factor to warrant BMD measurement. Younger males (50–69 years) should be assessed if they have additional risk factors, such as fractures, after 50 years of age or causes of secondary osteoporosis (Table 1).12,9,13–17 FRAX or other fracture risk calculators may improve fracture risk evaluation and the selection of patients for treatment.18,19

TreatmentGeneral measuresRecommendation- -

We suggest, as general measures, the practice of regular physical activity, smoking cessation, the avoidance of excess alcohol consumption, adequate calcium intake, and adequate 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels (2⊕⊕OO).

- -

We recommend specific actions and advice to prevent falls in elderly patients (1⊕OOO).

General measures for fracture prevention are important in the treatment of osteoporosis. However, their effect on fracture reduction has not been assessed.12,17 The prevention of falls is an effective measure to prevent osteoporotic fractures.20–23

Calcium and vitamin DRecommendations- -

We recommend the provision of 1000–1200mg of calcium and at least 800IU of vitamin D daily, including supplements if the minimum levels are not achieved (1⊕OOO).

There have been few studies in males assessing treatment with calcium and vitamin D supplements, all of them with small sample sizes, and including populations with different degrees of vitamin D deficiency or calcium intake. The results have been highly variable, with a neutral or protective effect on fractures.12,9,13–24

BisphosphonatesRecommendation- -

We suggest oral bisphosphonates as drugs of choice for the treatment of osteoporosis in males (2⊕⊕OO).

- -

We suggest intravenous zoledronate in patients with esophageal changes, gastrointestinal intolerance to oral bisphosphonates or an inability to remain in an upright position for 30min after taking the drug (2⊕⊕OO).

The effectiveness of alendronate against fractures in males has been studied in at least two meta-analyses. Sawka et al. noted a significant reduction in the risk of vertebral fractures (odds ratio [OR] 0.44; 95% confidence interval [IC]: 0.23–0.83). For non-vertebral fractures, the OR was 0.60 (95% CI: 0.29–1.44), not statistically significant, probably because of the low number of non-vertebral fractures seen.26 In a more recent meta-analysis27 of 988 males without osteoporosis, alendronate increased BMD by 4.95% in lumbar spine, 2.59% in femoral neck, and 2.39% in total hip. The risk reduction of vertebral fractures was 0.46 (95% CI: 0.28–0.77). Risedronate has also been evaluated in males with osteoporosis, with similar results.28–30

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in 1199 males with osteoporosis, either primary or secondary to hypogonadism, tested the effect of zoledronate (5mg IV at baseline and 12 months) on the risk of morphometric vertebral fractures. At 24 months, fewer vertebral fractures were seen in the zoledronate group, with a relative risk (RR) of 0.33 (95% CI: 0.16–0.70). No significant differences were seen in clinical vertebral or non-vertebral fractures, and the rates of serious adverse effects were similar.31

The overall efficacy of bisphosphonates in male osteoporosis was assessed in two recent meta-analyses.32,33 A meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials (5 with alendronate, 2 with risedronate, one with zoledronate and one with ibandronate) in which secondary osteoporosis was excluded, confirmed the efficacy of bisphosphonates in reducing the risk of vertebral and non-vertebral fractures: the RR for vertebral fractures was 0.36 (95% CI: 0.24–0.56), and for non-vertebral fractures 0.52 (95% CI: 0.32–0.84). However, no significant reduction was seen in the risk of clinical fractures and clinical vertebral fractures.6

DenosumabRecommendation- -

We suggest denosumab in patients intolerant or unresponsive to bisphosphonates, or with kidney failure (2⊕⊕OO).

A randomized trial versus placebo in 228 males showed that denosumab (60mg/6 months) for two years increased lumbar BMD by 8%, BMD in femoral neck by 3.4%, and BMD in total hip by 3.4%. There were no differences between the groups in the fracture rate.33,34

TeriparatideRecommendations- -

We suggest that treatment with teriparatide is effective for decreasing the risk of new vertebral fractures in males with primary osteoporosis (2⊕⊕OO).

In a study conducted in 437 males with primary osteoporosis, treatment with teriparatide was found to significantly increase BMD in the lumbar spine and femoral neck as compared to placebo. At 18 months of follow-up, there was a lower incidence of new vertebral fractures in the teriparatide groups, with an 83% reduction in the RR of new vertebral fractures.35

Finkelstein et al. randomized 83 males to alendronate (10mg daily), teriparatide (40μg daily) or combined therapy for 30 months (with teriparatide therapy from month 6). After 30 months, BMD in the lumbar spine and femoral neck significantly increased in the teriparatide group as compared to the two other groups (alendronate alone or the combination).36,37

Indications for treatment and treatment selectionRecommendation- -

We suggest that the intervention thresholds for females should also be applied to males: T-scores ≤2.5 SD or the presence of fragility fractures (2⊕⊕OO).

- -

We suggest the use of oral bisphosphonates (alendronate or risedronate) as first-line agents and zoledronate, denosumab, or teriparatide in specific situations (2⊕⊕OO).

Very few studies with specific data for males are available. However, there is no evidence suggesting that results associated with drug treatment are different in males and females when based on similar BMD values.35 Male data are extrapolated from studies including women with T scores −2.5 or less, or those who have sustained fragility fractures.38

The selection of a drug for males should be based on the clinical characteristics of the patient, potential interactions with underlying comorbidities or other treatments, the severity of osteoporosis, and patient preferences. Specific recommendations cannot be made based on the available evidence. However, baseline fracture risk and drug cost and efficacy in reducing fracture risk or increasing BMD should be taken into account.39

Generic formulations of alendronate and risedronate are the first-choice drugs in most cases because of their low cost. In males in whom oral bisphosphonates are not tolerated or contraindicated, zoledronic acid or denosumab are effective alternatives. In more severe cases (multiple vertebral fractures), teriparatide followed by an antiresorptive agent is a suitable option.

Treatment duration and follow-upMonitoringRecommendation- -

We suggest the measurement of lumbar and femoral BMD using DXA every 1–2 years in males on antiosteoporotic treatment (2⊕⊕OO).

- -

We suggest the measurement of BRMs (C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen [CTX] or amino-terminal propeptide of type I collagen [PINP]), especially in patients with inadequate response to treatment or suspected low treatment compliance (2⊕OO).

The Endocrine Society suggests the measurement of BMD by DXA every 1–2 years and a longer interval after the densitometric plateau is reached.9,40,41 The presence of stability or an increase above the minimum significant change should be considered an adequate response.42 A lack of response should suggest low treatment adherence or the presence of secondary causes.9

The measurement of BRMs in males with osteoporosis is controversial. The Endocrine Society suggests the measurement of serum CTX or N-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen (NTX) in serum or urine (antiresorptive therapy) and P1NP (anabolic treatment) 3–6 months after treatment start.9 This recommendation is based on an extrapolation of the results in women with post-menopausal osteoporosis, in whom changes in BRMs in response to treatment are related to lower fracture risk.43,44 It is not fully established what should be considered an adequate response to treatment, and it has been proposed that a change from baseline by approximately 40% (a decrease in subjects on antiresorptive therapy and an increase in those on anabolic treatment) or values below the mean range for young males could be considered an optimum response.9 The absence of the expected changes should suggest low treatment compliance, the existence of a secondary cause, or the possibility of a change in treatment.

Treatment durationRecommendation- -

We suggest for males the same treatment periods as those used in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis (2⊕OOO).

The incidence of adverse effects (mandibular osteonecrosis, atypical fracture) after long-term treatment with bisphosphonates does not appear to be higher in males as compared to females, and the algorithm proposed by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR)45 is therefore accepted. In this regard, after treatment for 3 (intravenous zoledronate) or 5 (oral bisphosphonate) years, the treatment should be continued, or a treatment switch should be considered in patients who have sustained a fracture during the active treatment phase, have a femoral T-score ≤−2.5, or have a high fracture risk based on age or other concomitant risk factors (e.g. treatment of androgen deficiency). As regards all other subjects, the drug treatment may be discontinued and retreatment reassessed every 2–3 years. As in females, the duration of teriparatide treatment should not exceed 24 months,46 while the maximum duration of treatment with denosumab has not been established.

Special situationsHypogonadismRecommendation- -

We recommend the measurement of BMD in patients with hypogonadism (1⊕⊕⊕O).

- -

We suggest that for males at a high risk of fracture who are on treatment with testosterone, an effective drug for reducing the risk of fracture (bisphosphonates, denosumab, or teriparatide) should be added (2⊕OOO).

- -

We suggest treatment with testosterone in males at a high risk of fracture and baseline total testosterone levels <200ng/dL if the use of other drugs for osteoporosis is contraindicated (2⊕⊕OO).

Any disease associated with testosterone deficiency may be associated with decreases in BMD.9,47–51 Randomized studies in patients with total testosterone levels <300–350ng/dL have shown that treatment with testosterone is associated with increases in BMD values in lumbar spine (2.7–9%) and total hip (0.8–3%) after 12–36 months of treatment with testosterone.52–54 However, BMD in femoral neck only improved in a randomized study and in an 8-year open label study.55 In males under 50 years of age, treatment with testosterone for 24–30 months has been associated with increased BMD in lumbar spine, with no changes in femoral neck or total hip.49,56 These studies had several limitations, such as small sample size, variable follow-up, and great heterogeneity in the characteristics of the population. No scientific evidence regarding the effect of treatment with testosterone on the risk of fracture has been reported.57

Two previously published clinical practice guidelines proposed the use of bisphosphonates, denosumab, or teriparatide in males with hypogonadism and a high risk of fracture.9,58 The benefits of these treatments were extrapolated from studies conducted in the general male population in which fracture risk reductions were seen in subgroups of patients with hypogonadism treated with alendronate31 and zoledronate.25

Prostate cancerRecommendation- -

We recommend DXA and X-rays to assess potential vertebral fractures at the start of treatment with GnRH agonists or after orchiectomy in patients with prostate cancer, and every 12 months thereafter during treatment with GnRH agonists (1⊕⊕⊕O).

- -

We recommend that treatment with denosumab or bisphosphonates be given to patients with cancer on androgen deficiency therapy who have T-scores less than −2 or a history of fragility fractures (1⊕⊕OO).

- -

We suggest that antiresorptive treatment should be given to patients with prostate cancer on androgen deficiency therapy who have T-scores ranging from 1 to −2 when they have other risk factors for osteoporosis (2⊕⊕OO).

GnRH agonists (goserelin, triptorelin, leuprolide) used in advanced prostate cancer induce bone mass loss and an increased fracture incidence.58

In these patients, zoledronic acid has been shown to increase BMD as compared to placebo by 6.7–7.8% in lumbar spine and by 2.6–3.9% in total hip, but no data are available as regards fracture reduction.59–61 Treatment with alendronate also induces bone mass gain, but no fracture data are available either.62–65

Denosumab is the only drug that has been shown to decrease the incidence of new fractures in patients with prostate cancer. After 36 months of treatment, the risks of new vertebral fractures and any new fracture decreased by 62% and 28% respectively.65,66 Treatment with teriparatide is not recommended for patients with bone metastases, including micrometastases or hidden disease.66

Conflicts of interestManuel Muñoz Torres is an advisory board member (Amgen, UCB, Shire) and lecturer (Amgen, Lilly).

Guillermo Martínez Díaz-Guerra is an advisory board member (Lilly, Amgen) and lecturer (Lilly, Amgen).

Esteban Jódar Gimeno is an advisory board member (Amgen, UCB, Shire) and lecturer (Amgen, Lilly).

The following authors reported no conflicts of interest regarding the preparation of this document: Verónica Ávila Rubio, Mariela Varsavsky, Antonía García Martín, Manuel Romero Muñoz, Antonio Becerra, Pedro Rozas Moreno.

Please cite this article as: Varsavsky M, Romero Muñoz M, Ávila Rubio V, Becerra A, García Martín A, Martínez Díaz-Guerra G, et al. Documento de consenso de osteoporosis del varón. Endocrinol Nutr. 2018;65:9–16.