It is recommended to periodically evaluate the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM1). Despite this, no specific paediatric HRQoL instrument for DM1 has been validated in Spanish.

ObjectivesMulticentre, prospective descriptive study in children and adolescents with DM1 with the aim of carrying out cross-cultural adaptation to Spanish and evaluating the reliability and validity of the DISABKIDS chronic disease and diabetes-specific HRQoL questionnaires, using reverse translation.

Material and methodsSociodemographic variables were compiled together with the most recent capillary glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) value and HRQoL questionnaires were handed out to 200 Spanish children and adolescents with DM1 aged between 8 and 18 years of age under evaluation in 12 different hospitals.

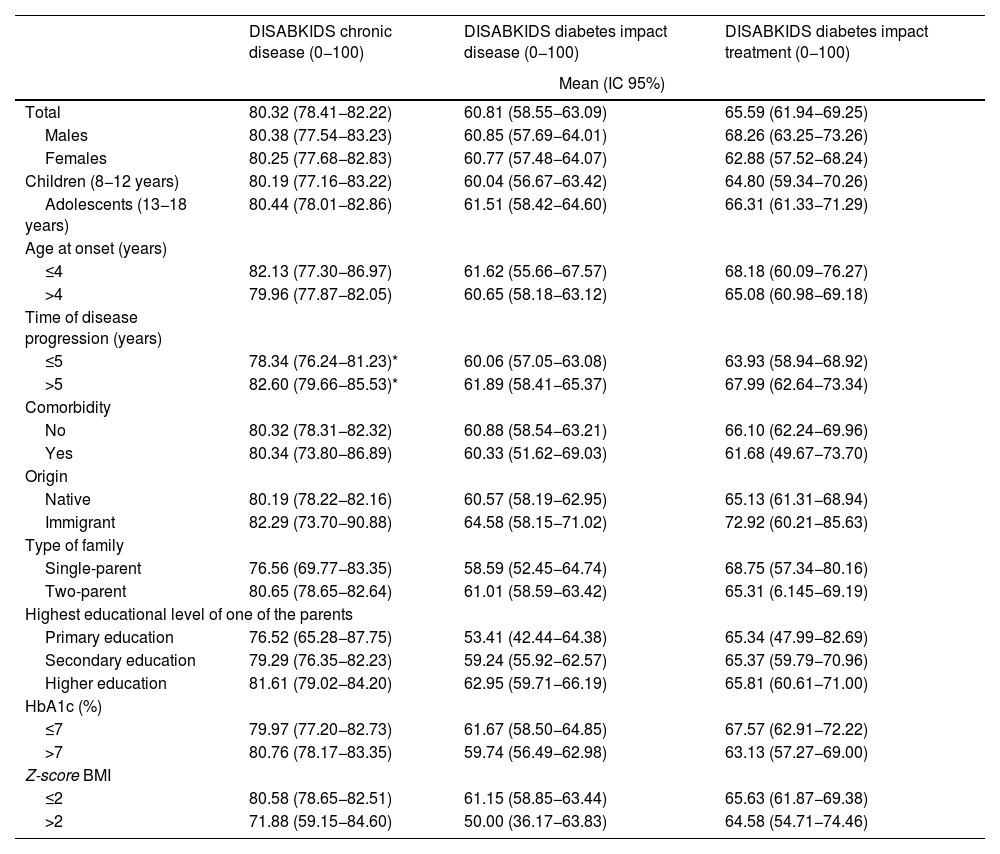

ResultsThe mean score on the HRQoL questionnaire (patient version) for chronic disease was 80.32 (13.66), being significantly lower (P = .04) in patients with a shorter duration of the disease (≤5 years): 78.34 (13.70) vs. 82.60 (13.36). The mean score of the DM1-specific modules was: 60.81 (16.23) for disease impact and 65.59 (26.19) for treatment impact.

The mean HbA1c value was 7.08 (0.79), with no differences (P > .05) noted in the mean score of the HRQoL instruments in patients with HbA1c ≤7% vs. HbA1c >7%.

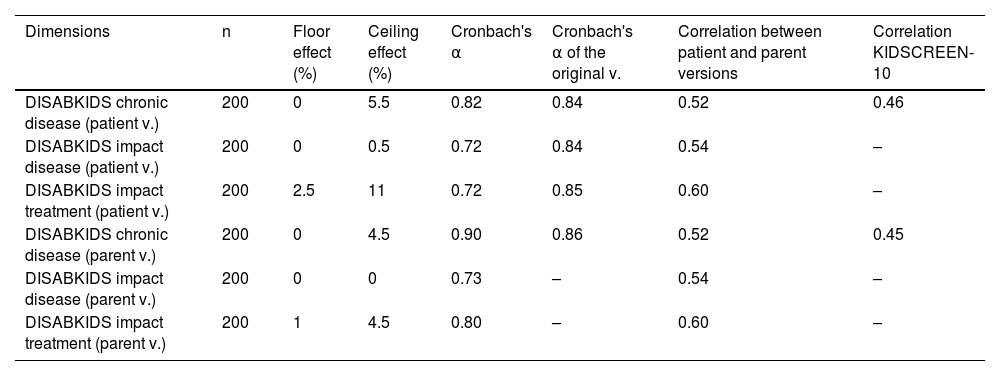

The Cronbach α value varied between 0.72 and 0.90.

ConclusionsThe Spanish versions of the DISABKIDS HRQoL instruments meet the proposed objectives of semantic equivalence and internal consistency, making it possible to periodically assess HRQoL in these patients.

The good average glycaemic control presented by the patients may explain why no difference was found in the HRQoL instruments based on the HbA1c value.

Se recomienda evaluar de forma periódica la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) en niños y adolescentes con Diabetes Mellitus tipo 1 (DM1). A pesar de ello, no se encuentra validado ningún instrumento de CVRS pediátrico específico de DM1 en español.

ObjetivosEstudio descriptivo transversal multicéntrico en niños y adolescentes con DM1 con el objetivo de realizar la adaptación transcultural al español y evaluar la fiabilidad y validez de los CVRS DISABKIDS enfermedad crónica y específico de Diabetes mediante el método de traducción inversa.

Material y métodosSe recogieron variables sociodemográficas, el último valor de hemoglobina glicosilada capilar (HbA1c) y se entregaron los cuestionarios de CVRS a 200 niños y adolescentes españoles con DM1 entre 8 y 18 años, en seguimiento en 12 hospitales.

ResultadosLa puntuación media del CVRS (versión para pacientes) genérico de enfermedad crónica fue 80,32 (13,66), siendo significativamente menor (p:0,04) en los pacientes con menor tiempo de evolución de la enfermedad (≤5 años): 78,34 (13,70) vs 82,60 (13,36). La puntuación media de los módulos específicos de DM1 fue: impacto de enfermedad: 60,81 (16,23) e impacto de tratamiento: 65,59 (26,19).

El valor medio de HbA1c fue de 7,08 (0,79), no constatándose diferencias (P > ,05) en la puntuación media de los instrumentos de CVRS en los pacientes con HbA1c ≤ 7% vs HbA1c >7%.

El valor del α de Cronbach en las diferentes dimensiones varió entre el 0,72 y 0,90.

ConclusionesLas versiones en español de los instrumentos de CVRS DISABKIDS validados cumplen los objetivos propuestos de equivalencia semántica y consistencia interna, posibilitando evaluar de forma periódica la CVRS en estos pacientes.

El buen control glucémico medio que presentaban los pacientes puede explicar que no se encontrase diferencia en los instrumentos de CVRS en función del valor de HbA1c.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM1) is a chronic disease common in infants and adolescents, with an approximate prevalence in Spain of 1.2/1000 inhabitants.1 The management of DM1 in childhood requires monitoring capillary blood glucose, counting portions of carbohydrate, and administration of insulin.2 Technological advances, such as interstitial glucose monitoring systems and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion pumps, have made it possible to optimise glycaemic control; nonetheless, diabetes care continues to have a major impact on the everyday life of patients and their families.3

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is defined as an individual's perception of the state of their health and it represents the impact that a disease has on different physical, emotional and social aspects of life.4 The HRQoL can be evaluated by means of HRQoL questionnaires, which are classified as generic when they include all the dimensions that comprise the HRQoL or specific if they evaluate one particular disease.5

For several years, the case has been put forward for measuring the HRQoL In children and adolescents with DM1, with the recommendation of periodically evaluating the HRQoL in these patients being reflected in the latest clinical guidelines from the International Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD), from 2018.6,7 Despite the benefits of having a specific HRQoL instrument for children and adolescents with DM1, a questionnaire of these characteristics in Spanish has yet to be validated.

DISABKIDS is a European project led by the University of Hamburg, developed simultaneously in several countries, including six languages, aimed at improving the quality of life and independence of children suffering from chronic diseases, as well as that of their families.8 In order to meet this objective, a series of standardised HRQoL Questionnaires in paediatric patients from different European countries have been developed, making it possible to generically evaluate the HRQoL in both chronic illness and in different specific pathologies, including DM1.8 These questionnaires have been validated in a number of different European languages but not in Spanish.9,10

With the aim of adapting to Spanish and studying the reliability and validity of the DISABKIDS Questionnaires, Chronic disease and diabetes module, Version for patients and parents, the following study was designed.

MethodologyAfter requesting authorisation from the European centre which designed the study, the process of adaptation and analysis of reliability and validity commenced.

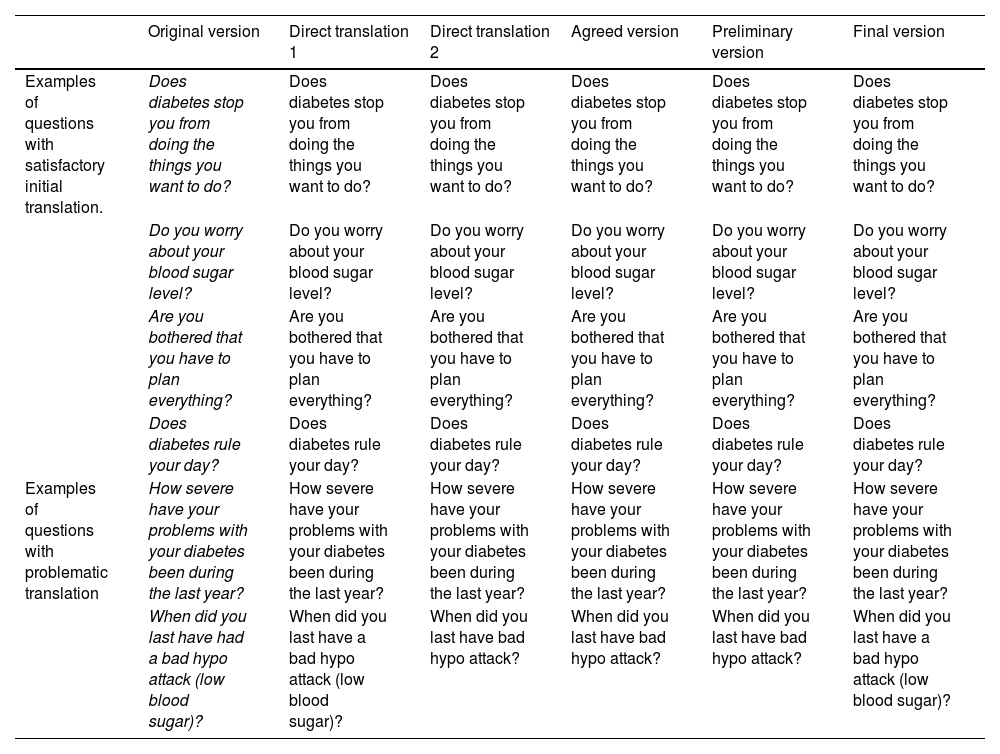

The HRQoL questionnaires were translated into Spanish using the back-translation method (Fig. 1), in which professional translators experienced in the health setting independently translated the original questionnaires into our language. In the next step, the two forward translators, along with the Principal Investigators, prepared an agreed version, ensuring compliance with the conceptual equivalence requirements of the original questionnaire in English. Subsequently, a third translator performed the back translation into English and translated this version into our language, obtaining the preliminary version.

The preliminary version was evaluated (pretest) on 12 paediatric patients with DM1 and their parents, during follow-up in the Paediatric Diabetes Unit of a tertiary hospital.

A descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out using the collection of epidemiological and clinical variables and the delivery of questionnaires on HRQoL in children and adolescents with DM1 under follow-up in paediatric diabetes units in 12 Spanish hospitals (nine tertiary and three secondary hospitals) from seven different regions, and their parents. The inclusion criteria were as follows: between 8 and 18 years of age, having a diagnosis of DM1 with more than six months of disease progression, and agreeing to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were a diagnosis of DM1 with less than six months of disease progression, and no consent to participate in the study. The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the hospital from which the study was managed (no. 37/19).

The patients were recruited during a six-month period by means of consecutive sampling, until a minimum number of 15–20 patients per centre was reached. The parents who agreed to participate in the study signed the informed consent form and authorisation for their children's participation in the research project. Those participants over the age of 12 also signed the informed consent form.

Socio-demographic variables were collected. Comorbidity was defined as the existence of a DM1-related autoimmune disease or the diagnosis of another chronic disease, unrelated to DM1, which required follow-up in a specialised clinic. Glycaemic control was evaluated with the value of the latest glycosylated haemoglobin from capillary blood test (HbA1c) performed and the weight-height ratio by means of calculating the z-score of the body mass index (BMI) (Estudio Transversal Español de Crecimiento [Spanish Cross-sectional Growth Study], 2010).

Questionnaires administeredIn a peaceful setting, and over a period of approximately 20−25 min, the patients and their parents filled in the following HRQoL questionnaires: KIDSCREEN-10, DISABKIDS chronic diseases (short version) and DISABKIDS diabetes, patient and parent versions, respectively.

The DISABKIDS Chronic diseases questionnaire (short version) comprises 12 questions, obtaining a score from 0 a 100, with a higher score corresponding to a higher HRQoL.

The DISABKIDS diabetes questionnaires comprise 10 Questions and two dimensions which reflect the impact of the disease and treatment in the HRQoL. Each dimensional scored is also scored from 0 to 100.

Statistical analyses were performed with the software program SPSS Statistics V. 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach's α, a parameter which measures each item's degree of convergence with respect to its corresponding dimension. The floor and ceiling effect of each questionnaire was also analysed. The proposed objective was that the value of the ceiling effect and the floor effect of each dimension should be below 15%, and that the Cronbach's α value should be higher than 0.70. The external validity of the DISABKIDS HRQoL for chronic disease (version and patients), was measured by means of a correlation analysis with the corresponding version of the KIDSCREEN-10 questionnaire.11

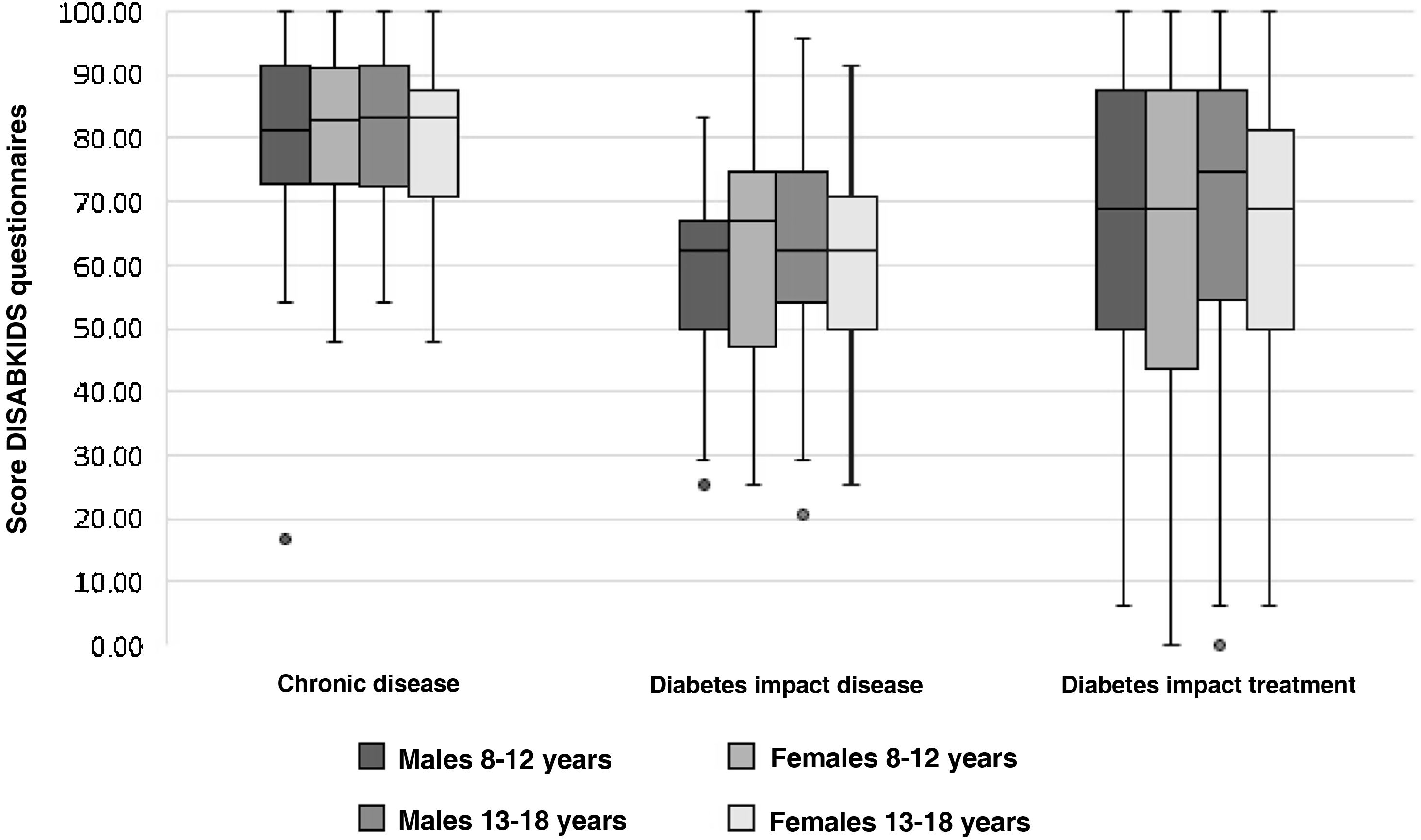

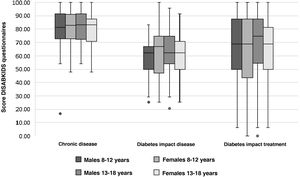

The score for each dimension was compared according to the current age and at the onset of the illness, sex, time of progression from diagnosis, presence or not comorbidity, native or immigrant origin, highest educational level of one of the parents, latest HbA1c test performed, and standard deviation (SD) of the BMI. The mean value of each dimension and its 95% Confidence interval (CI) was calculated on the basis of the aforesaid epidemiological and clinical variables. The score of each scale was also compared on the basis of four groups divided by sex and age: 8−12 years and 13−18 years.

The discriminant validity was evaluated by means of the hypothesis that adolescents, and girls, and those patients with worst glycaemic control would obtain lower mean scores in the HRQoL instruments.

Throughout the research project, the following have been respected: Organic Law 3/2018 of 5 December on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights and Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons about the processing of personal data and the free movement of such data.

ResultsOf an initial sample of 213 cases, 13 were excluded owing to incomplete collection of the variables in question. In the final sample of 200 Cases, there were no lost values in the collection of the items that make up the different questionnaires.

During the process of adapting the questionnaires, there were problematic questions and items which required multiple changes, while in others they were maintained unchanged after the initial translation (Table 1). After holding a videoconference with the European studies centre, the final corrections were implemented, with the delivery of the final version in Spanish to the collaborating hospitals being authorised.

Translation of the patient version of the DISABKIDS Diabetes health-related quality of life questionnaire: classification of questions according to their difficulty in translation and maintenance of conceptual equivalence.

| Original version | Direct translation 1 | Direct translation 2 | Agreed version | Preliminary version | Final version | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Examples of questions with satisfactory initial translation. | Does diabetes stop you from doing the things you want to do? | Does diabetes stop you from doing the things you want to do? | Does diabetes stop you from doing the things you want to do? | Does diabetes stop you from doing the things you want to do? | Does diabetes stop you from doing the things you want to do? | Does diabetes stop you from doing the things you want to do? |

| Do you worry about your blood sugar level? | Do you worry about your blood sugar level? | Do you worry about your blood sugar level? | Do you worry about your blood sugar level? | Do you worry about your blood sugar level? | Do you worry about your blood sugar level? | |

| Are you bothered that you have to plan everything? | Are you bothered that you have to plan everything? | Are you bothered that you have to plan everything? | Are you bothered that you have to plan everything? | Are you bothered that you have to plan everything? | Are you bothered that you have to plan everything? | |

| Does diabetes rule your day? | Does diabetes rule your day? | Does diabetes rule your day? | Does diabetes rule your day? | Does diabetes rule your day? | Does diabetes rule your day? | |

| Examples of questions with problematic translation | How severe have your problems with your diabetes been during the last year? | How severe have your problems with your diabetes been during the last year? | How severe have your problems with your diabetes been during the last year? | How severe have your problems with your diabetes been during the last year? | How severe have your problems with your diabetes been during the last year? | How severe have your problems with your diabetes been during the last year? |

| When did you last have had a bad hypo attack (low blood sugar)? | When did you last have a bad hypo attack (low blood sugar)? | When did you last have bad hypo attack? | When did you last have bad hypo attack? | When did you last have bad hypo attack? | When did you last have a bad hypo attack (low blood sugar)? |

Table 2 shows the sociodemographic and clinical variables of all patients evaluated. 50.5% of the participants were male. The distribution by age group was similar, with 95 patients belonging to the group aged between 8 and 12 years, and the remaining 105 to the group aged between 13 and 18 years. The mean value of the final HbA1c test performed was 7.08%, and 55.5% of the participants presented an HbA1c value lower than or equal to 7%.

Socio-demographic and clinical variable of the participants.

| Variables | n | Mean (SD) or % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Males | 101 | 50.5% |

| Females | 99 | 49.5% |

| Age (years) | ||

| Total | 200 | 13.09 (2.39) |

| 8-12 | 95 | 11.04 (1.37) |

| 13-18 | 105 | 14.95 (1.40) |

| Age at onset (years) | ||

| Total | 200 | 7.81 (3.42) |

| ≤4 | 33 | 2.41 (0.90) |

| >4 | 167 | 8.87 (2.64) |

| Time of disease progression (years) | ||

| Total | 200 | 5.28 (3.35) |

| ≤5 | 118 | 2.93 (1.30) |

| >5 | 82 | 8.66 (2.34) |

| Comorbidity | ||

| No | 177 | 88.5% |

| Yes | 23 | 11.5% |

| Origin | ||

| Native | 188 | 94% |

| Immigrant | 12 | 6% |

| Type of family | ||

| Single-parent | 16 | 8% |

| Two-parent | 184 | 92% |

| Highest educational level of one of the parents | ||

| Primary education | 11 | 5.5% |

| Secondary education | 87 | 43.5% |

| Higher education | 102 | 51% |

| Hba1c (%) | ||

| Total | 200 | 7.08 (0.79) |

| ≤7 | 111 | 6.55 (0.35) |

| >7 | 89 | 7.75 (0.66) |

| Z-score BMI | ||

| Total | 200 | 0.58 (0.92) |

| ≤2 | 194 | -0.03 (0.79) |

| >2 | 6 | 2.80 (0.56) |

HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin from capillary blood test; BMI: body mass index.

Table 3 shows the values for the ceiling effect, floor effect, internal consistency, correlation between the versions for patients and parents, and external consistency for the dimensions of the HRQoL questionnaires evaluated. No floor effect was observed, and the percentage of the ceiling effect was lower than the proposed target in all dimensions. The internal consistency was high, with the Cronbach's α value varying between 0.72 in the lowest dimension and 0.90 in the highest. The Cronbach's α value for the original questionnaires is similar with regard to the generic questionnaire, and discretely higher in the specific modules for diabetes. The DISABKIDS Chronic disease questionnaire shows a mean correlation (r = 0.52) between the versions for patients and parents, being significantly lower than the correlation between versions of the original questionnaire (r = 0.82). The correlation between the versions for patients and parents in the specific dimensions for diabetes was moderate (0.54 and 0.60) and similar to the correlation between patients and parents in the original versions (0.50 and 0.50). The external correlation between the score for the DISABKIDS chronic disease questionnaire is and the KIDSCREEN-10 generic questionnaires was discrete (0.46 and 0.45).

Floor effect, ceiling effect, internal consistency, correlation between patient version and parent version, and external consistency in the dimensions of the health-related quality of life questionnaires evaluated.

| Dimensions | n | Floor effect (%) | Ceiling effect (%) | Cronbach's α | Cronbach's α of the original v. | Correlation between patient and parent versions | Correlation KIDSCREEN-10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DISABKIDS chronic disease (patient v.) | 200 | 0 | 5.5 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.52 | 0.46 |

| DISABKIDS impact disease (patient v.) | 200 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 0.54 | – |

| DISABKIDS impact treatment (patient v.) | 200 | 2.5 | 11 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.60 | – |

| DISABKIDS chronic disease (parent v.) | 200 | 0 | 4.5 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.45 |

| DISABKIDS impact disease (parent v.) | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0.73 | – | 0.54 | – |

| DISABKIDS impact treatment (parent v.) | 200 | 1 | 4.5 | 0.80 | – | 0.60 | – |

v.: version.

Table 4 shows the mean scores for the parents' version of the DISABKIDS chronic disease questionnaire and the two dimensions of the DISABKIDS Diabetes Questionnaire (impact of the disease and impact of the treatment), both globally and on the basis of the variables referred to above. The mean total score for the DISABKIDS chronic disease questionnaire was 80.32 (13.66), high in comparison with the total scores for the specific diabetes dimensions: 60.81 (6.23) and 65.59 (26.19), respectively. No differences were found in the scores for the HRQoL instruments analysed separately according to gender or age group or jointly according to four age groups and sex (Fig. 2). Generally speaking, there were no differences in the means of the scores, analysed according to the sociodemographic variables described above, with the exception of a lower score, in a significant manner (P = .04), in the generic HRQoL instrument for chronic disease in the group of patients with the shortest time of disease progression since the onset: 78.34 (13.70) vs. 82.60 (13.36).

Mean scores for the dimensions of the HRQoL questionnaires (patient version): DISABKIDS chronic disease; DISABKIDS diabetes, impact of disease and DISABKIDS diabetes, impact of treatment, total and according to socio-demographic variables.

| DISABKIDS chronic disease (0−100) | DISABKIDS diabetes impact disease (0−100) | DISABKIDS diabetes impact treatment (0−100) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (IC 95%) | |||

| Total | 80.32 (78.41−82.22) | 60.81 (58.55−63.09) | 65.59 (61.94−69.25) |

| Males | 80.38 (77.54−83.23) | 60.85 (57.69−64.01) | 68.26 (63.25−73.26) |

| Females | 80.25 (77.68−82.83) | 60.77 (57.48−64.07) | 62.88 (57.52−68.24) |

| Children (8−12 years) | 80.19 (77.16−83.22) | 60.04 (56.67−63.42) | 64.80 (59.34−70.26) |

| Adolescents (13−18 years) | 80.44 (78.01−82.86) | 61.51 (58.42−64.60) | 66.31 (61.33−71.29) |

| Age at onset (years) | |||

| ≤4 | 82.13 (77.30−86.97) | 61.62 (55.66−67.57) | 68.18 (60.09−76.27) |

| >4 | 79.96 (77.87−82.05) | 60.65 (58.18−63.12) | 65.08 (60.98−69.18) |

| Time of disease progression (years) | |||

| ≤5 | 78.34 (76.24−81.23)* | 60.06 (57.05−63.08) | 63.93 (58.94−68.92) |

| >5 | 82.60 (79.66−85.53)* | 61.89 (58.41−65.37) | 67.99 (62.64−73.34) |

| Comorbidity | |||

| No | 80.32 (78.31−82.32) | 60.88 (58.54−63.21) | 66.10 (62.24−69.96) |

| Yes | 80.34 (73.80−86.89) | 60.33 (51.62−69.03) | 61.68 (49.67−73.70) |

| Origin | |||

| Native | 80.19 (78.22−82.16) | 60.57 (58.19−62.95) | 65.13 (61.31−68.94) |

| Immigrant | 82.29 (73.70−90.88) | 64.58 (58.15−71.02) | 72.92 (60.21−85.63) |

| Type of family | |||

| Single-parent | 76.56 (69.77−83.35) | 58.59 (52.45−64.74) | 68.75 (57.34−80.16) |

| Two-parent | 80.65 (78.65−82.64) | 61.01 (58.59−63.42) | 65.31 (6.145−69.19) |

| Highest educational level of one of the parents | |||

| Primary education | 76.52 (65.28−87.75) | 53.41 (42.44−64.38) | 65.34 (47.99−82.69) |

| Secondary education | 79.29 (76.35−82.23) | 59.24 (55.92−62.57) | 65.37 (59.79−70.96) |

| Higher education | 81.61 (79.02−84.20) | 62.95 (59.71−66.19) | 65.81 (60.61−71.00) |

| HbA1c (%) | |||

| ≤7 | 79.97 (77.20−82.73) | 61.67 (58.50−64.85) | 67.57 (62.91−72.22) |

| >7 | 80.76 (78.17−83.35) | 59.74 (56.49−62.98) | 63.13 (57.27−69.00) |

| Z-score BMI | |||

| ≤2 | 80.58 (78.65−82.51) | 61.15 (58.85−63.44) | 65.63 (61.87−69.38) |

| >2 | 71.88 (59.15−84.60) | 50.00 (36.17−63.83) | 64.58 (54.71−74.46) |

HbA1c and BMI (n = 200).

CI: confidence interval; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin from capillary blood test; BMI: body mass index.

Bivariate analysis (Student's t test), multivariate analysis of variance (ANOVA).

In this study, the patient and parent versions of the HRQoL questionnaire, DISABKIDS chronic disease (short version) and specific for diabetes, have been cross-culturally adapted into Spanish to provide an HRQoL instrument that makes it possible to study the HRQoL of Spanish children and adolescents with DM1. The translation was performed using the back translation method, adhering to the recommendations of the European centre that designed the study. The pertinent corrections were made in the preliminary version to obtain the definitive version.

The versions in Spanish of the instruments of the DISABKIDS Chronic disease and DISABKIDS diabetes HRQoLs have appropriate semantic equivalence, which was achieved through a rigorous validation process.

The mean value and standard deviation of the scores for the HRQoL instruments were similar to those obtained in children and adolescents with DM1 in the original version. The reliability is comparable to the original version, with the hypothesis of high internal consistency and low ceiling and floor effect values being met. In a similar way to the study carried out by Rajmil et al. in a paediatric and adolescent population without chronic disease, the correlation between the scores for the patient and parent versions of the HRQoL Instrument was moderate.12 The analysis of the correlation between the scores for the DISABKIDS and KIDSCREEN-10 dimensions of chronic disease was discrete; it has been reported that the external reproducibility of some dimensions of paediatric-age-specific chronic disease instruments can sometimes be poor, owing to the difference in the conceptualisation of the same dimensions between the different questionnaires.13 For example, unlike the KIDSCREEN-10, the dimension on physical well-being in the DISABKIDS chronic disease questionnaire includes questions that evaluate the influence of medical treatment on the HRQoL.

Our patients present high perceived quality of life scores, evaluated by the generic instrument, DISABKIDS for chronic diseases. They express greater effect on their quality of life in relation to the impact of diabetes and its treatment. The lower scores obtained in the dimensions specific to diabetes reflect the increased capacity of the specific test for this chronic disease to detect the burden entails those issued specific to DM, different from other chronic diseases.14

Despite the fact that, in both the general population and in patients with DM1, women are traditionally described as scoring worse in HRQoL instruments,15,16 in our sample, there was no difference in the score for HRQoL questionnaires according to sex, or to age group.

The group of patients with the shortest time of disease progression since the onset scored significantly worse in the chronic disease scale; in the rest of the sociodemographic variables analysed, no relation with HRQoL was found. These findings may indicate that the HRQoL perceived by the patient should not be prejudged according to socio-demographic variables. Therefore, without the routine evaluation of HRQoL, patients with greater impact on the HRQoL could go unnoticed.

The patients presented a mean value for HbA1c of less than 7.5%, classically indicative of good glycaemic control, and in 55.5% of them, the value of the HbA1c performed was below 7%, the current strictest threshold, defined as the target for glycaemic control in the latest international consensus guidelines.17 This good glycaemic control could explain why, in our patients, there was no difference in the quality of life between those with HbA1c <7% and HbA1c >7%, in contrast to the studies by Murillo et al. and Anderson et al. in children and adolescents with DM1, which describe a direct relationship between a higher HbA1c value a poorer score in HRQoL instruments.18,19

Svensson et al. compared the version of DISABKIDS chronic disease and the specific modules for diabetes in three Nordic countries; it was found that, in the version where the largest number of responses were not directly translatable from the original version, the complexity of the questionnaire increased.20

The fact that no difficulties understanding the wording of the questions and answers that make up the final version of the questionnaire were notified by either patients or parents makes the trans-cultural adaptation to Spanish robust.

The other principal strengths of the study are the availability of a broad sample of patients, along with the multi-centred design comprising different types of hospitals from different regions.

The main limitations are its cross-sectional design, which makes it impossible to obtain a ratio between glycaemic control and the rest of the epidemiological variables in the HRQoL, as well as the lack of assessment of test-retest reliability.

By way of conclusion, we consider that the availability of the questionnaires adapted to Spanish offers practical utility since, with a short period of administration, they make it possible to periodically evaluate the HRQoL of children and adolescents with DM1, adhering to the recommendation of the latest ISPAD guidelines. Moreover, validating the Generic DISABKIDS Chronic Disease Instrument could be a step further towards incorporating HRQoL instruments into paediatric clinical practice.

FundingThis work has been funded by a grant from the trustees of the «Ernesto Sánchez Villares» Foundation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank all the children, teenagers and parents who have participated in this study. We would also like to thank Dr. Luis Rajmil for his recommendations in preparing the discussion of the manuscript.