The participation of transgender women (TW) in high-level competitive sports increases every year, as does the interest of sports organizations in finding solutions that allow their inclusion without compromising the principle of equity governing high-level sports. However, the binary categorization of sports, influenced by the impact of sex hormone on physical performance, creates challenges for the inclusion of TW in the female category. This study aimed to understand the impact of gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) on various athletic performance variables and to compare results with those obtained in cisgender populations.

MethodsReview of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies that included TW (preferably athletes) undergoing GAHT.

ResultsSignificant decreases in hematocrit, total serum testosterone, lean body mass, strength, and muscle area were observed after 12 mo of GAHT, with increases in fat mass. Grip strength was higher in TW compared to cisgender females (CW) in the long term. TW showed better performance in sports involving the upper body.

ConclusionsAt least 2 years of postpubertal GAHT are necessary to achieve a significant reduction in the effects of male hormones on various physiological parameters. The scientific evidence regarding the impact of GAHT on physical performance is insufficient. Long-term studies are needed, incorporating new biomarkers and morphofunctional parameters, to allow for comparisons of athletic performance across different disciplines between TW and CW.

La participación de mujeres transgénero (MT) en el deporte de alta competición aumenta cada año, al igual que la necesidad de los organismos deportivos por buscar soluciones que permitan su inclusión sin comprometer el principio de equidad que rige el deporte de alto nivel. La categorización diferenciada por sexo dificulta la inclusión de MT en la categoría femenina. El objetivo de este estudio fue conocer el impacto del tratamiento hormonal afirmativo de género (THAG) sobre el rendimiento deportivo y comparar los resultados con los obtenidos en población cisgénero.

Material y métodosRevisión de estudios transversales y longitudinales que incluyeron MT (preferentemente deportistas) bajo THAG.

ResultadosSe observaron descensos significativos en hematocrito, testosterona total plasmática (TT), masa libre de grasa (MLG), fuerza y área muscular con incrementos en masa grasa tras 12 meses en THAG. La fuerza de agarre fue superior en MT frente a mujeres cisgénero (MC) a largo plazo. En MT, se evidenció mejor rendimiento en deportes con implicación del tren superior.

ConclusionesSon necesarios al menos 2 años de THAG de inicio pospuberal para conseguir una disminución significativa de los efectos de las hormonas masculinas sobre diferentes parámetros fisiológicos. La evidencia científica de la repercusión del THAG en el rendimiento físico de la MT es insuficiente. Se precisan estudios a más largo plazo, con nuevos biomarcadores y parámetros morfofuncionales, que permitan comparar el rendimiento deportivo en las distintas disciplinas entre MT y MC.

High-performance sports aim to achieve peak athletic performance in elite competitions. Sports where success depends on strength, speed, or endurance are conventionally divided into male and female categories to promote perceived fairness in competition.1 However, this binary classification based on male and female categories does not account for transgender individuals who experience incongruence between their biological sex and gender identity.2

Historically, cisgender women (CW) have faced numerous obstacles in participating in competitive sports, such as family care responsibilities and lower funding, among others. This has resulted in the underrepresentation of CW in high-level championships3: at the 1928 Olympics, only 9.6% of participants were women (277 athletes).4 With advances in gender equality, the role of women in sports has grown significantly, with 47.8% female participation at the 2021 Tokyo Olympics (5,457 athletes), culminating in a record-breaking participation at the 2024 Paris Olympics, achieving gender parity.5 In Spain, regulations such as the European Charter for Sport for All, adopted by the Council of Europe in 1975, have contributed to promoting equal opportunities for women, serving as a framework to combat gender-based discrimination in sports.

The inclusion of transgender athletes in sports has undergone multiple changes. Initially, sports regulations did not specifically address the participation of transgender athletes, creating challenges and barriers to their inclusion in competitions. On the other hand, some have warned that the indiscriminate inclusion of transgender women (TW) in elite sports could disrupt the structure and organization of sports by undermining principles of fairness. Organizations such as the International Olympic Committee (IOC) have played a crucial role in evolving regulations for transgender athlete participation. These guidelines have shifted over time, from strict requirements such as gonadectomy to criteria based on total testosterone (TT) levels and duration of gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT),4,6

In 2003, the IOC proposed legal recognition of acquired gender, gonadectomy, and anti-androgenic treatment for at least 2 years. Afterwards, in 2015, the IOC required a maintained gender identity for at least 4 years and TT levels < 10 nmol/L for at least 1 year. In 2021, the IOC published the “Framework on Fairness, Inclusion, and Non-Discrimination on the Basis of Gender Identity and Sex Variations”,7 abandoning the need for anti-androgenic treatment, prioritizing the inclusion of all groups in sports,8 and delegating the regulation of transgender athlete participation to international federations (IFs). This regulation should also be nuanced according to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), which recognizes fairness in competitions as a legitimate and fundamental objective of competitive sports, allowing restrictions on individual rights to ensure fairness with a fair balance between competing interests (ECHR ruling, January 18th, 2018). Currently, some federations, such as Athletics9 and the World Boxing Council,10 have opted to exclude TW from female competitions to maintain fairness and safety. Others, like the Baseball Federation, allow their participation under the condition that TT levels remain below 10 nmol/L and medical statements from endocrinologists are provided. However, some federations, such as Skiing, have yet to establish specific regulations.

Sex-based categorization in elite sports is based on the discrepancy in androgen levels after puberty, particularly TT, which has significant implications for the cardiovascular system and musculoskeletal structure. On average, cisgender men (CM) have greater height, bone mineral density (BMD), muscle strength, hemoglobin concentration, and aerobic capacity (absolute and relative VO2 max) vs. CW. Performance differences vary by sport. On average, CM outperform CW by 10–12% in rowing, swimming, and running, 20% in jumping, and over 50% in throwing events (e.g., baseball).11 In TW, post-pubertal pharmacological suppression of TT levels for > 2 years leads to changes in body composition, including increased fat mass (FM) and decreased muscle mass and strength. However, other factors such as height, wingspan, and cardiorespiratory size remain unchanged.11 In cisgender populations, the differences between men and women in various sports are well-documented. In contrast, there is a lack of high-quality scientific literature evaluating the impact of GAHT or surgical treatment on physical performance in TW vs. CW.

The objectives of this literature review are to understand the current evidence on the effects of GAHT in TW on various factors impacting athletic performance: analytical parameters, body composition, BMD, muscle strength and area, and aerobic capacity; to assess the differences between TW and CW; and to evaluate the implications for elite sports competitions.

Following a critical and comprehensive literature review, members of the Endocrinology, Nutrition, and Physical Exercise Working Group (GT-GENEFSEEN) and the Gonad, Identity, and Sexual Differentiation Working Group (GT-GIDSEEN) of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition (SEEN) met to analyze the physiological differences between CW and TW in sports. In planning this meeting, the coordinators requested volunteers from both groups based on availability and interest in the topic, selecting a total of 6 members, all of whom were medical specialists in Endocrinology and Nutrition. Additionally, the director of the Women and Sports Seminar at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (Madrid, Spain) participated in the article review.

Materials and methodsSearch strategiesWe conducted a search across the PubMed and Embase databases. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms from the Index Medicus, such as “transgender athletes”, were combined with the AND operator, along with several synonyms of the term. Articles published from January 2018 through March 2024 in Spanish and English were included. After obtaining the initial search results, duplicate citations, comments on articles, and case reports were removed. Following the analysis of titles and abstracts, the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied.

Inclusion criteriaStudies that measured the effects of GAHT on analytical parameters, body composition, bone health, muscle strength, and aerobic capacity were included, provided they met the following requirements: 1) studies with TW who completed puberty before starting GAHT with a minimum duration of 6 mo, and 2) comparative studies between TW on GAHT and cisgender individuals.

Exclusion criteriaSingle case reports; 2) studies with results obtained from surveys or questionnaires; and 3) studies unrelated to the topic or with insufficient data extraction.

Additionally, complementary articles were identified from the bibliographic sources of already selected articles.

Subsequently, we conducted a full reading of the selected articles and a critical narrative review incorporating the most relevant aspects.

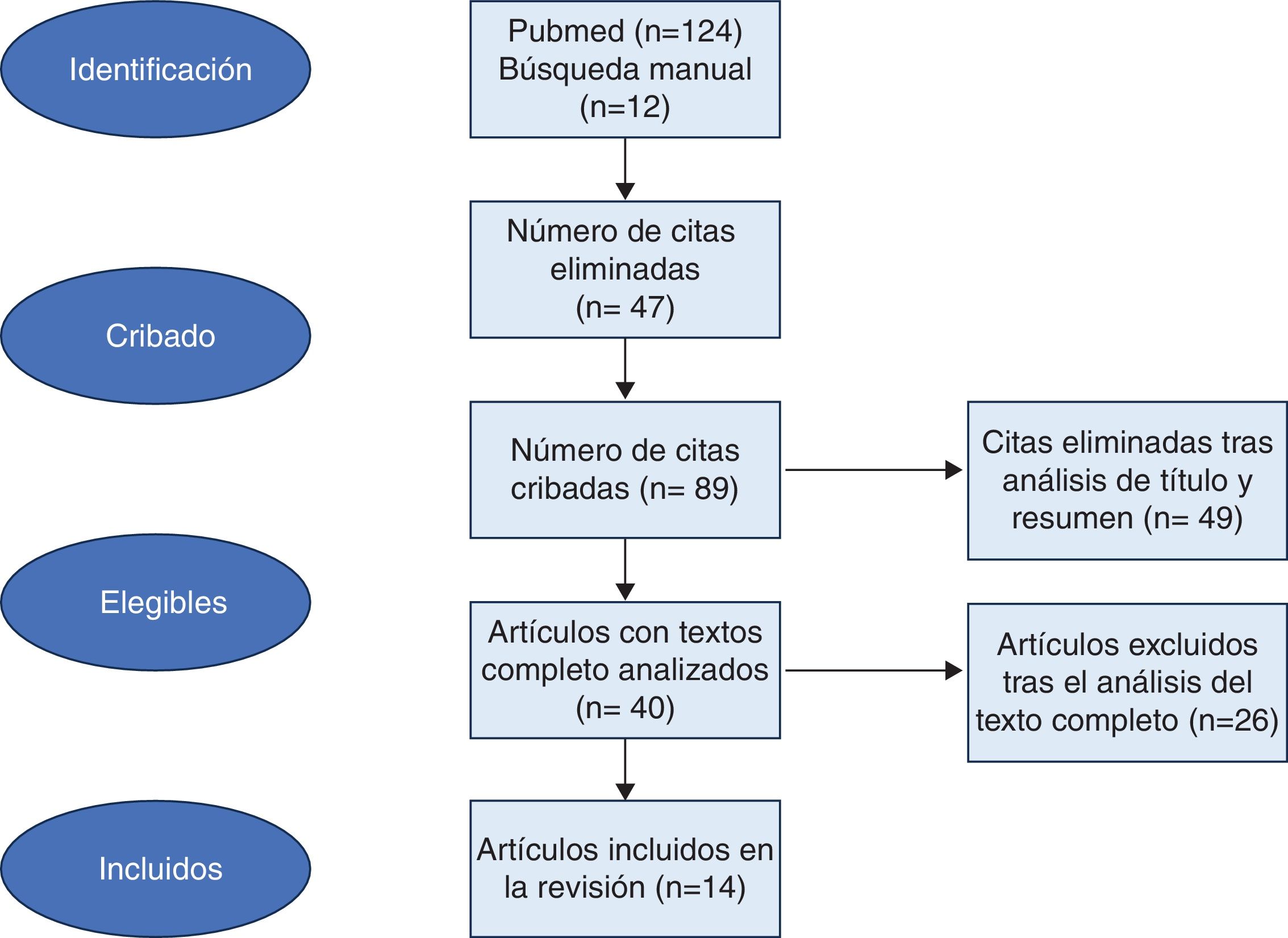

ResultsA total of 136 studies were included, of which 47 duplicates were removed, leaving a total of 89 articles. After applying inclusion/exclusion criteria to titles and abstracts, a total of 49 studies were excluded, and 40 articles were subjected to full reading. Finally, 14 studies met the inclusion criteria. All articles were descriptive studies (Fig. 1).

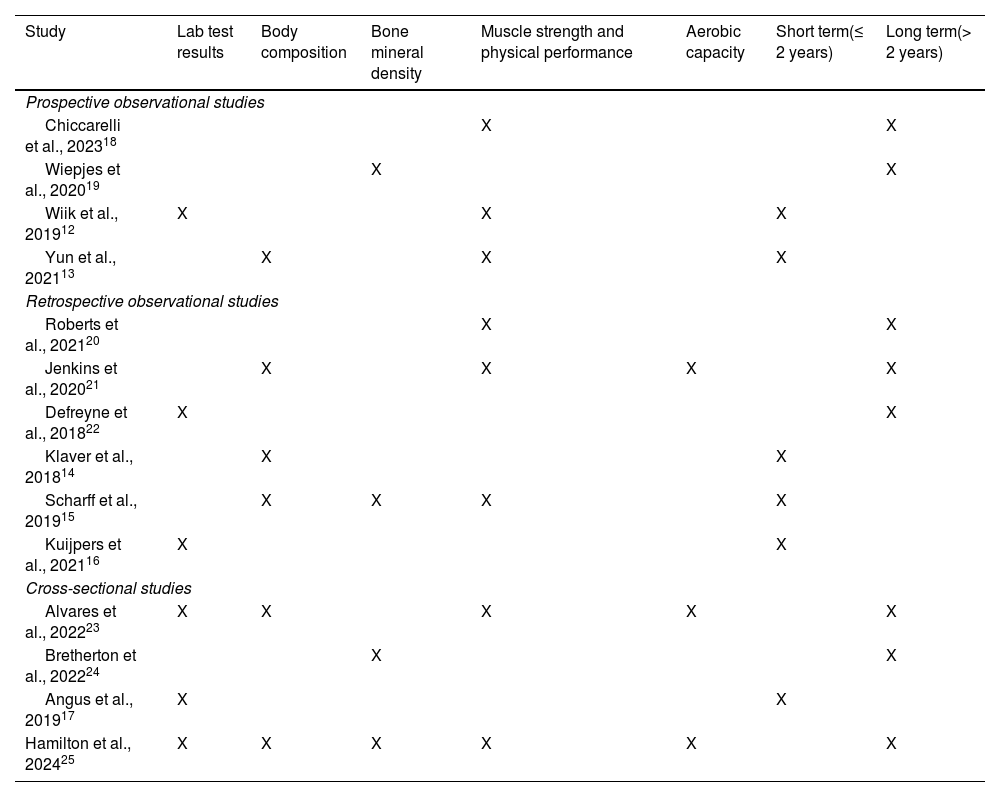

Table 1 illustrates the impact of GAHT on the evaluated clinical variables, classified as short- (study period ≤ 2 years)12–17 and long-term (study period > 2 years).18–25

Clinical variables and time on GAHT at the time of outcome assessment of the main studies.

| Study | Lab test results | Body composition | Bone mineral density | Muscle strength and physical performance | Aerobic capacity | Short term(≤ 2 years) | Long term(> 2 years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective observational studies | |||||||

| Chiccarelli et al., 202318 | X | X | |||||

| Wiepjes et al., 202019 | X | X | |||||

| Wiik et al., 201912 | X | X | X | ||||

| Yun et al., 202113 | X | X | X | ||||

| Retrospective observational studies | |||||||

| Roberts et al., 202120 | X | X | |||||

| Jenkins et al., 202021 | X | X | X | X | |||

| Defreyne et al., 201822 | X | X | |||||

| Klaver et al., 201814 | X | X | |||||

| Scharff et al., 201915 | X | X | X | X | |||

| Kuijpers et al., 202116 | X | X | |||||

| Cross-sectional studies | |||||||

| Alvares et al., 202223 | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Bretherton et al., 202224 | X | X | |||||

| Angus et al., 201917 | X | X | |||||

| Hamilton et al., 202425 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

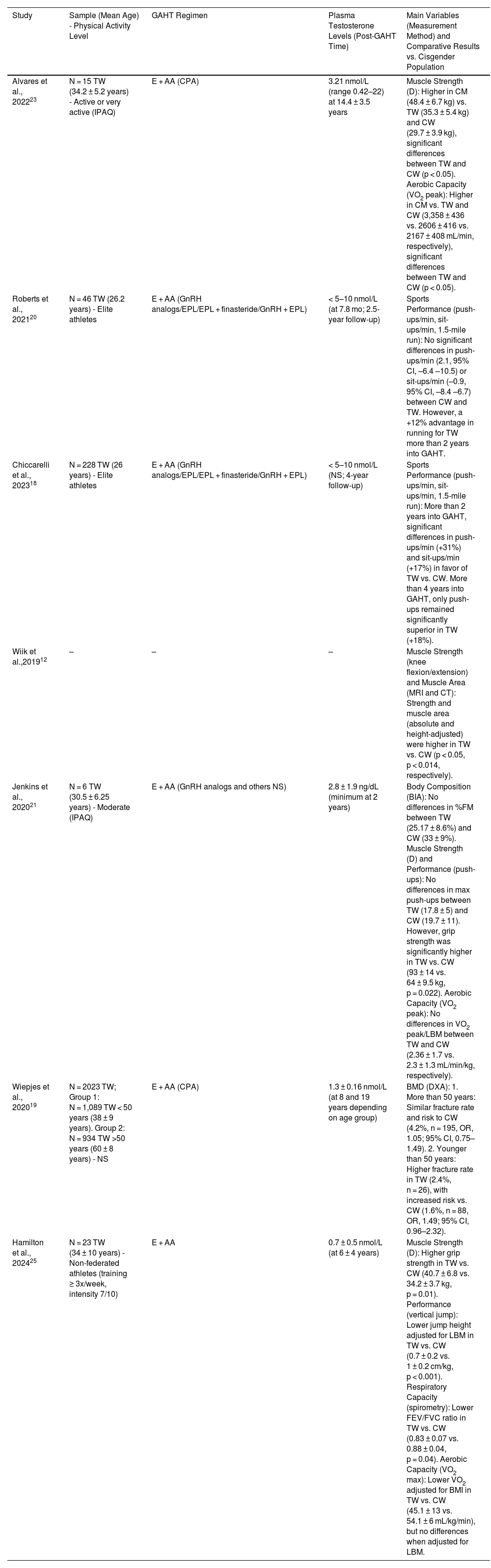

The methodology and main results of studies comparing TW and CW are summarized in Table 2. Seven studies included a control group of CW,18–21,23,25 of which only 218,20 included elite TW athletes.

Description of methodological aspects and main findings of studies with comparative outcome variables between transgender and cisgender women.

| Study | Sample (Mean Age) - Physical Activity Level | GAHT Regimen | Plasma Testosterone Levels (Post-GAHT Time) | Main Variables (Measurement Method) and Comparative Results vs. Cisgender Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvares et al., 202223 | N = 15 TW (34.2 ± 5.2 years) - Active or very active (IPAQ) | E + AA (CPA) | 3.21 nmol/L (range 0.42–22) at 14.4 ± 3.5 years | Muscle Strength (D): Higher in CM (48.4 ± 6.7 kg) vs. TW (35.3 ± 5.4 kg) and CW (29.7 ± 3.9 kg), significant differences between TW and CW (p < 0.05). Aerobic Capacity (VO2 peak): Higher in CM vs. TW and CW (3,358 ± 436 vs. 2606 ± 416 vs. 2167 ± 408 mL/min, respectively), significant differences between TW and CW (p < 0.05). |

| Roberts et al., 202120 | N = 46 TW (26.2 years) - Elite athletes | E + AA (GnRH analogs/EPL/EPL + finasteride/GnRH + EPL) | < 5–10 nmol/L (at 7.8 mo; 2.5-year follow-up) | Sports Performance (push-ups/min, sit-ups/min, 1.5-mile run): No significant differences in push-ups/min (2.1, 95% CI, –6.4 –10.5) or sit-ups/min (–0.9, 95% CI, –8.4 –6.7) between CW and TW. However, a +12% advantage in running for TW more than 2 years into GAHT. |

| Chiccarelli et al., 202318 | N = 228 TW (26 years) - Elite athletes | E + AA (GnRH analogs/EPL/EPL + finasteride/GnRH + EPL) | < 5–10 nmol/L (NS; 4-year follow-up) | Sports Performance (push-ups/min, sit-ups/min, 1.5-mile run): More than 2 years into GAHT, significant differences in push-ups/min (+31%) and sit-ups/min (+17%) in favor of TW vs. CW. More than 4 years into GAHT, only push-ups remained significantly superior in TW (+18%). |

| Wiik et al.,201912 | – | – | – | Muscle Strength (knee flexion/extension) and Muscle Area (MRI and CT): Strength and muscle area (absolute and height-adjusted) were higher in TW vs. CW (p < 0.05, p < 0.014, respectively). |

| Jenkins et al., 202021 | N = 6 TW (30.5 ± 6.25 years) - Moderate (IPAQ) | E + AA (GnRH analogs and others NS) | 2.8 ± 1.9 ng/dL (minimum at 2 years) | Body Composition (BIA): No differences in %FM between TW (25.17 ± 8.6%) and CW (33 ± 9%). Muscle Strength (D) and Performance (push-ups): No differences in max push-ups between TW (17.8 ± 5) and CW (19.7 ± 11). However, grip strength was significantly higher in TW vs. CW (93 ± 14 vs. 64 ± 9.5 kg, p = 0.022). Aerobic Capacity (VO2 peak): No differences in VO2 peak/LBM between TW and CW (2.36 ± 1.7 vs. 2.3 ± 1.3 mL/min/kg, respectively). |

| Wiepjes et al., 202019 | N = 2023 TW; Group 1: N = 1,089 TW < 50 years (38 ± 9 years). Group 2: N = 934 TW >50 years (60 ± 8 years) - NS | E + AA (CPA) | 1.3 ± 0.16 nmol/L (at 8 and 19 years depending on age group) | BMD (DXA): 1. More than 50 years: Similar fracture rate and risk to CW (4.2%, n = 195, OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.75–1.49). 2. Younger than 50 years: Higher fracture rate in TW (2.4%, n = 26), with increased risk vs. CW (1.6%, n = 88, OR, 1.49; 95% CI, 0.96–2.32). |

| Hamilton et al., 202425 | N = 23 TW (34 ± 10 years) - Non-federated athletes (training ≥ 3x/week, intensity 7/10) | E + AA | 0.7 ± 0.5 nmol/L (at 6 ± 4 years) | Muscle Strength (D): Higher grip strength in TW vs. CW (40.7 ± 6.8 vs. 34.2 ± 3.7 kg, p = 0.01). Performance (vertical jump): Lower jump height adjusted for LBM in TW vs. CW (0.7 ± 0.2 vs. 1 ± 0.2 cm/kg, p < 0.001). Respiratory Capacity (spirometry): Lower FEV/FVC ratio in TW vs. CW (0.83 ± 0.07 vs. 0.88 ± 0.04, p = 0.04). Aerobic Capacity (VO2 max): Lower VO2 adjusted for BMI in TW vs. CW (45.1 ± 13 vs. 54.1 ± 6 mL/kg/min), but no differences when adjusted for LBM. |

AA: antiandrogens; CPA: cyproterone acetate; GnRH: gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs; BIA: bioimpedance analysis; D: dynamometry; BMD: bone mineral density; DXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; E: estradiol; EPL: spironolactone; CM: cisgender men; CW: cisgender women; IPAQ: international physical activity questionnaire; FM: fat mass; LBM: lean body mass; TW: transgender women; NS: not specified; CT: computed tomography; VO2: oxygen volume.

Hematologically, an observational study with a sample of 239 TW from the European Network for the Investigation of Gender Incongruence (ENIGI) registry26 showed a 4.1% decrease in hematocrit (Hct) levels (95% CI, 3.50–4.37, p < 0.001), dropping from 45.1% (42.7–47.5) at baseline down to 41.0% (39.9–43) at 3 mo into GAHT; these levels were maintained 3 years into GAHT. There were no differences in the percentage decrease in Hct based on the route of estrogen administration (p = 0.864), although a positive correlation was found between Hct levels and TT (r = 0.501, p < 0.001).22 Similarly, another sample of TW on long-term GAHT (14.4 ± 3.5 years) also showed notable reductions in hemoglobin (Hb) levels without statistically significant differences vs. CW (14 ± 0.15 vs. 13.8 ± 0.17 g/dL). Both TW on long-term GAHT and CW had significantly lower Hb levels vs. CM (15.3 ± 0.29 g/dL, p < 0.0001).23

Regarding TT levels (measured by competitive immunoassay in all cases), 2 recent studies were found. The first included a total of 114 TW on GAHT for a mean 1.5 years and observed that those onestradiol and cyproterone acetate (CPA) (mean dose of 50 mg/day) had significantly lower TT levels (0.8 nmol/L) vs. those treated with estradiol and spironolactone (SPL) (2 nmol/L; mean dose of 100 mg/day) or oral estradiol (10.5 nmol/L, mean dose of 6 mg/day). A total of 90% of the CPA group and 40% of the SPL group had mean TT concentrations within the physiological range of CW (0.4–2 nmol/L).17 The second study, from the ENIGI registry cohort, evaluated the effects of estradiol plus CPA at different doses in TW (n = 882) and found that a dose of 10 mg/day of CPA was as effective as higher doses (25, 50, or 100 mg/day) and that only 3 mo of GAHT were needed to achieve suppressed TT levels (< 2 nmol/L).16 Regarding estradiol levels, a recent study of 23 TW athletes found significantly higher levels vs. CW (742 ± 801 vs. 336 ± 266 pmol/L, p = 0.045).25

Effects of GAHT on body compositionIn adult TW, changes in body composition (measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry [DXA]) vary by body region. An observational study of 179 TW with a mean age of 29 and, at least, 1 year of GAHT found the greatest reductions in lean body mass (LBM) in the arms (–5 down to –7%) and legs (–3 down to –4%), with smaller changes in gynoid (–2 down to –3%) and android (–1 down to +2%) regions 12 mo into GAHT. Regarding FM variations, the overall FM increased by 9–32%, primarily in the legs (+37 up to +47%) and to a lesser extent in the trunk (+16 up to +25%).14 Similarly, a subsequent study of 11 TW with a mean age of 28.5 years on a 6-mo regimen of GAHT showed a 16.2% increase in the overall FM, mainly in the trunk (18%), legs (27.4%), and gynoid regions (27.2%), resulting in a lower android/gynoid FM ratio vs. baseline. Conversely, LBM decreased primarily in the arms (–8%) and trunk (–3%).13

Long-term, 2 studies found changes in body composition. The first, conducted in a cohort of female athletes (including TW with a mean GAHT duration of 6 ± 4 years), found higher BMI-adjusted FM in TW vs. CW (8.2 ± 4.5 vs. 5.5 ± 1.6 kg/m2, p = 0.04), along with a higher android/gynoid FM ratio in TW vs. CW (0.97 ± 0.2 vs. 0.78 ± 0.08, p = 0.001). Additionally, absolute LBM was significantly higher in TW vs. CW (52.4 ± 7.6 vs. 40.3 ± 3.8, p < 0.001), although no differences were found after BMI adjustment.25 The second study described the effects of GAHT measured at 14 ± 3.5 years of treatment: the overall FM percentage was significantly lower in CM vs. TW and CW (20.2 vs. 29.5 vs. 32.9%, p < 0.05, respectively), and age-adjusted LBM percentage was lower in CM vs. TW and CW (20.5 vs. 18.3 vs. 15.8 kg/m2, p < 0.05, respectively), although there were no significant differences between TW and CW in these parameters.23

Effects of GAHT on bone mineral density (BMD)Two studies evaluated the long-term effects of GAHT on BMD. One compared TW on a 3-year regimen of GAHT (n = 40, mean age 37.6 ± 13.2 years) to CM (n = 51, mean age 41.6 ± 11 years) using high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) of the tibia and distal radius. Results showed that total volumetric BMD (vBMD), cortical vBMD, and cortical thickness were significantly lower in TW vs. CM (–0.68 SD, p = 0.01; –0.7 SD, p < 0.01; –0.51 SD, p = 0.04, respectively). Additionally, cortical porosity was higher in TW vs. CM (0.7 SD; p < 0.01).24 These findings are consistent with another study concluding that TW more than 50 years on long-term GAHT (mean 19 years) had a higher rate and risk of fracture (4.4%, n = 41) vs. CM (2.4%, n = 110, OR = 1.90, 95% CI, 1.32–2.74).19

Effects of GAHT on muscle strength, muscle area, and athletic performanceRegarding muscle strength, several studies13,15,21,23,25 measured grip strength using dynamometry. A cohort of 249 TW from the ENIGI registry showed a –1.8 kg (95% CI, –2.6; –1) decrease in grip strength after the first year into GAHT. A total of 66% of this decrease occurred within the first 3 mo of GAHT. These changes were similar across age, BMI, and estrogen administration groups. Additionally, no association was found between grip strength reduction and changes in LBM and BMD.15 Yun et al.13 also observed a –7.7% (p = 0.0467) decrease in grip strength 6 mo into GAHT. However, despite this decline, grip strength remained significantly higher in TW vs. CW > 2 years into GAHT (93 ± 14 vs. 64 ± 9.5 kg; p = 0.022, d = 1.78).21 These findings are consistent with another study of TW athletes on long-term GAHT (6 ± 4 years) showing higher grip strength in TW vs. CW, even after adjusting for hand surface area or LBM.25

Regarding muscle area, Wiik et al.12 measured quadriceps thickness using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) in a sample of 11 TW with low-to-moderate aerobic physical activity levels. They observed a 5% reduction in total quadriceps thickness (p < 0.01) and a 4% reduction in cross-sectional area (p < 0.05) 1 year into GAHT. However, 12 mo into GAHT, absolute and height-adjusted strength levels remained higher in TW vs. transgender men and CW.

Regarding athletic performance, two studies focused on elite TW athletes. The first compared the physical performance of 46 TW pre- and post-GAHT to the mean performance of CW and CM younger than 30 years in the Air Force between 2004 and 2014. Two years into GAHT, physical performance (number of push-ups and sit-ups) equalized between groups, but differences remained in middle-distance running times (+12%).20 A subsequent study with a larger sample (n = 228 TW) and longer follow-up (4 years) found that physical performance (number of sit-ups and running time) equalized more than 2 years into GAHT. Differences in push-ups (+18% vs. the control group [CW]) remained significantly higher in TW vs. CW 4 years into GAHT.18 Regarding lower body performance, Hamilton et al. observed that 6 ± 4 years into GAHT, TW had a lower vertical jump height adjusted for LBM vs. non-federated CW athletes (training at least 3 times per week).25

Effects of GAHT on cardiopulmonary and aerobic capacityRegarding respiratory function, Hamilton et al.25 measured forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) using spirometry, finding higher values in TW vs. CW (4.2 ± 0.6 vs. 3.5 ± 0.4 L, p < 0.001; 5.1 ± 0.6 vs. 3.9 ± 0.5 L, p < 0.001, respectively), although the FEV1/FVC ratio was significantly lower in TW.

Regarding aerobic capacity, a cross-sectional study evaluated the effects of long-term GAHT (14 ± 3.5 years) in 11 TW with mean TT levels of 3.21 nmol/L and high or very high physical activity levels according to the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). They found significantly higher peak VO2 levels in CM vs. TW and CW (3,358 ± 436 vs. 2,606 ± 416 vs. 2,167 ± 408 mL/min, p < 0.05, respectively). This superiority in absolute peak VO2 was also significant in TW vs. CW; however, when adjusted for weight and LBM, these differences were no longer statistically significant.23 These results were corroborated by two other studies in female athletes25 and individuals with moderate physical activity levels,21 with no differences observed after adjusting peak VO2 for LBM.

DiscussionVarious studies have been conducted on the impact of GAHT on parameters related to physical performance in TW. However, scientific evidence of its effects remains scarce due to the lack of clinical trials. At analytical level, Hct, Hb, and TT levels significantly decreased in the initial phases of GAHT and remained stable in the long term, within the CW27 range.

TT has been the only biomarker used to establish eligibility criteria, with maximum permitted levels set at 5 nmol/L.11 However, additional or supportive parameters such as the TT/estradiol or TT/cortisol ratios28 could also be considered. Another aspect to consider is the type of antiandrogen used to suppress TT levels, as some drugs alter the physiological function of testosterone regardless of its plasma levels.

It is crucial to standardize values and testosterone measurement methods. These measurements should always be performed using the same method, with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) being the most accurate, allowing simultaneous measurement of other steroids, though it is not always readily available.

On the other hand, there is no direct correlation between testosterone levels and physical performance,11 making it useful to conduct a morphofunctional assessment that considers parameters such as body composition, muscle strength, cardiorespiratory capacity (VO2 peak adjusted for weight and LBM), and aerobic capacity.

Regarding body composition, the overall FM increased while total LBM decreased, with significant changes observed in varying degrees depending on the body region more than 6 mo into GAHT. BMI-adjusted FM and age-adjusted LBM remained higher in TW vs. CW in the long term. In terms of BMD, worse outcomes were observed in TW vs. CM before the age of 50, with an increased rate and risk of fractures vs. MC after the age of 50. Muscle strength and muscle area decreased in the short term; however, grip strength remained higher in TW vs. CW in the long term.

In terms of physical performance, results are more heterogeneous. Generally, in the long term, TW shows better performance than CW in physical activities involving the upper body (e.g., push-ups)29 vs. activities relying on the lower body (e.g., running or vertical jumping).25 However, it is not possible to make direct comparisons as these results have not been adjusted for different variables of interest (age, height, BMI, or LBM). Regarding lung function, worse spirometric results were observed in TW vs. CM, with lower aerobic capacity (according to maximum VO2). However, when comparing TW vs. CW with VO2 peak adjusted for weight and LBM, no statistically significant differences were found.

In conclusion, the available scientific evidence on changes in various physiological variables that may influence the athletic performance of TW in GAHT depends on several factors, such as:

- -

Dose, duration, and type of GAHT.

- -

Timing of GAHT initiation (pre- or post-pubertal).

- -

The sport practiced and the age of initiation.30

- -

Whether the individual competed before starting GAHT.

A literature review identified several significant limitations. Firstly, the number of studies comparing TW with CW is very limited (Table 2), making it impossible to match for age, height, or BMI, among other variables, which may lead to over- or underestimation of the effects of GAHT. Additionally, even in studies including cisgender populations, only 3 studies adjusted results for weight,23 height,12,23 or LBM.12,21,23 No studies have yet compared athletic performance between transgender individuals who began treatment with prepubertal blockers vs. those who started GAHT after puberty. Although this is not within the objectives of this review, it would be of great interest to conduct studies in this area. Furthermore, most reviewed studies included non-elite athlete populations,12,19,21–25 making it questionable to extrapolate results to individuals participating in high-performance and competitive sports. Other limitations include the lack of well-controlled longitudinal studies over the long term, small sample sizes, the use of heterogeneous and sometimes indirect outcome measurement methods, and the lack of categorization based on different sports disciplines.

Regarding sports regulations, the IOC urges all sports organizations to base their eligibility criteria on high-quality scientific evidence. In the absence of such evidence, the IOC published its latest guidelines in 2021 for “fair, equal, and inclusive representation in sports”.7 Among the principles mentioned are “inclusion” and “non-discrimination” based on gender identity, expression, or variations; the principles of “harm prevention” and “fairness”; and the principle of “prioritizing health and bodily autonomy”, which states that no athlete should be subjected to medical procedures due to pressure from sports federations (FD). Additionally, this section urges the exclusion from competition of athletes who claim a gender identity different from the one consistently and persistently used for participation in a particular category.8

It is necessary to develop sports regulations based on scientific findings that promote fair participation for all athletes. Some federations have proposed introducing an ‘Open’ competition category, allowing all athletes, regardless of gender, to voluntarily participate as an alternative to their predetermined category.3 However, other federations have dismissed the widespread implementation of this proposal.

ConclusionsMore than 2 years of post-pubertal GAHT are necessary to achieve a significant reduction in the effects of male hormones on various physiological parameters. The current scientific evidence on the impact of GAHT on physical performance is insufficient. Long-term studies with new biomarkers and morphofunctional parameters are needed to compare athletic performance across different disciplines between TW and CW.

Such studies should be considered by the IOC and FD to develop new evidence-based guidelines and regulations to ensure the protection of the rights of all athletes (CW and TW).

This research has not received any specific support from public sector agencies, commercial sector or non-profit entities.