Dulaglutide and semaglutide are once-weekly administered GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) indicated for the treatment of hyperglycemia in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2).

ObjectiveTo evaluate the efficacy and safety of switching from subcutaneous (SC) dulaglutide to SC semaglutide, in real-world conditions.

Materials and methodsA total of 123 individuals with T2DM on SC dulaglutide, either as monotherapy or with other antihyperglycemic drugs, who switched to SC semaglutide were included. This switch was motivated by insufficient reduction in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C), the need for greater weight loss, or gastrointestinal intolerance associated with dulaglutide. Changes with semaglutide in HbA1C and weight at 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo, as well as any changes in associated adverse effects. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

ResultsPrevious treatment with dulaglutide (duration 16.9 ± 13.8 mo) reduced HbA1c by 0.38% (p = 0.003 vs. baseline) and weight by −1.3 kg (p = 0.003 vs. baseline). After switching to semaglutide, an additional reduction in HbA1C levels was observed at 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo (−0.43%, p = 0.000; −0.54%, p = 0.000; −0.38%, p = 0.021; −0.12%, p = 0.622, respectively) and in weight at 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo (−2.7 kg, p = 0.000; −3.7 kg, p = 0.000; −5.4 kg, p = 0.001; −4.2 kg, p = 0.000, respectively) With no significant differences in the frequency of adverse effects after switching to semaglutide.

ConclusionsIn real-world conditions, switching dulaglutide to semaglutide in obese patients with T2DM is associated with an additional reduction in HbA1C and weight, without notable changes in the frequency of adverse effects.

Dulaglutida y semaglutida son agonistas del receptor de GLP-1 (AR-GLP-1) de administración semanal, utilizados en el tratamiento de la hiperglucemia en diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2) y obesidad (IMC ≥ 30 kg/m2).

ObjetivoEvaluar la eficacia y seguridad del cambio de dulaglutida subcutánea (SC) a semaglutida SC en condiciones de vida real.

Material y métodosSe incluyeron 123 personas con DM2 en tratamiento con dulaglutida SC, en monoterapia o combinación con otros fármacos antihiperglucemiantes, que cambiaron a semaglutida SC debido a una reducción insuficiente de la hemoglobina glicosilada (HbA1C), necesidad de mayor pérdida de peso, o intolerancia gastrointestinal a dulaglutida. Se analizaron los cambios en HbA1C y peso a los 6, 12, 18 y 24 meses, y la variación de los efectos adversos asociados. Los datos se expresan como media ± desviación estándar.

ResultadosEl tratamiento previo con dulaglutida (duración 16,9 ± 13,8 meses) se asoció con una reducción media de 0,38% en HbA1C (p = 0,003 vs. basal) y una pérdida de 1,3 kg (p = 0,003 vs. basal). Tras el cambio a semaglutida, se observó una reducción adicional en HbA1C a los 6, 12, 18 y 24 meses (-0,43%, p = 0,000; -0,54%, p = 0,000; -0,38%, p = 0,021; -0,12%, p = 0,622, respectivamente) y en peso (-2,7 kg, p = 0,000; -3,7 kg, p = 0,000; -5,4 kg, p = 0,001; -4,2 kg, p = 0,000, respectivamente). No hubo diferencias significativas en la frecuencia de efectos adversos.

ConclusionesEn condiciones de vida real, la transferencia de dulaglutida a semaglutida en pacientes con DM2 y obesidad se asocia con una reducción adicional de HbA1C y peso, sin cambios notables en la frecuencia de efectos adversos.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a 30-amino acid incretin hormone produced in the intestine with beneficial effects on glucose metabolism and appetite regulation. Its action stems from the stimulation of insulin secretion, the suppression of glucagon secretion, and the slowing of gastric emptying. Current therapeutic options to enhance incretin effects are the use of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibitors (iDPP4) and GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs). The latter are an established therapeutic option in the treatment of hyperglycemia in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and obesity. They act by mimicking the effect of GLP-1 to stimulate glucose-dependent insulin secretion, decrease postprandial glucagon secretion, and slow gastric emptying. All of this produces an anti-hyperglycemic effect, with a very low intrinsic risk of hypoglycemia.1–3 They also act on the central nervous system (CNS) by promoting satiety and reducing caloric intake, thereby contributing to weight loss.4–7 In addition, some GLP-1 RAs have demonstrated a reduction in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with T2DM, both in primary and secondary prevention, thus becoming the cornerstone of treatment along with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors (iSGLT2).8–10 Recently, we have achieved more evidence on the beneficial effect of GLP-1 RAs in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) through a multifactorial mechanism of action that is not yet fully understood but appears to improve liver damage by promoting a reduction in steatosis and inflammation. This new line of action is significant, as up to 70% of patients with T2DM suffer from NAFLD, and we do not have specific treatments to fight it.11

In patients with T2DM and obesity, weekly administered GLP-1 RAs (exenatide LAR, dulaglutide, and semaglutide) achieve greater reductions in HbA1c and more weight loss vs daily administered GLP-1 RAs with a shorter half-life (exenatide, liraglutide, lixisenatide). In comparative and randomized clinical trials, semaglutide has proven to be more effective than other GLP-1 RAs in reducing HbA1c, with dulaglutide being the second most potent in anti-hyperglycemic efficacy.12–15

The greater efficacy profile of semaglutide vs other GLP-1 RAs could be related to the structural characteristics of the molecule.16 It is a GLP-1 RA with 94% homology in the amino acid sequence with endogenous GLP-1, with 3 modifications in its structure that allow for a more prolonged binding to GLP-1 receptors and extend the half-life to approximately 1 week.17 Furthermore, being a small molecule, it can reach regions of the CNS involved in the control of food intake. This characteristic is attributed to the fact that weight loss with semaglutide is greater than that of other larger GLP-1 RAs such as dulaglutide, whose entry into the CNS is more limited.18

Although randomized clinical trials provide the greatest scientific evidence, they are limited on their external validity, since these studies often include selected patient populations that may not reflect real-world prescribing conditions,19 particularly with respect to changes between different GLP-1 RAs. There is limited real-world evidence on the effectiveness and possible adverse effects after switching from one GLP-1 RA to another. Published studies compared the transfer of daily or weekly administered GLP-1 RAs to weekly administered GLP-1 RAs20–22 demonstrating superiority in both HbA1c reduction and weight loss after switching from a daily or weekly GLP-1 RA to subcutaneous (SC) semaglutide.20–23 However, the studies found included a small number of patients previously on dulaglutide, the second most potent weekly administered GLP-1 RA in anti-hyperglycemic efficacy.

Therefore, the SEMA-SWITCH study was designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy profile, in real-world ions, of switching from weekly SC dulaglutide to weekly SC semaglutide. When collecting and analyzing the data, oral semaglutide was not marketed in Spain, and therefore was not included for comparisons in the study.

Material and methodsStudy designWe conducted a retrospective and observational study at Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia (HCUV) (Valencia, Spain).

Patient selectionAll prescriptions for weekly SC semaglutide in the HCUV area from May 2019 (launch date in Spain) through January 2021 were analyzed, finding a total of 482 patients. A sample of 123 of these patients who met the inclusion criteria was selected.

Inclusion criteria were adult patients (≥ 18 years) with a diagnosis of T2DM and a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2 who, before starting treatment with weekly SC semaglutide, were or had previously received weekly SC dulaglutide.

Selected patients were those in whom the treatment change was made by specialist endocrinologists, thus ensuring proper collection and follow-up of information. Data were collected retrospectively from health records, supplemented with additional information obtained by telephone when necessary. Patients with incomplete data or who did not have a minimum follow-up of 6 mo after the therapeutic change were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 1).

Analyzed variables and follow-upDemographic and clinical data of the patients were collected, including age, sex, duration of diabetes, concomitant treatment (metformin, iSGLT2, and insulin), BMI, baseline HbA1c level, baseline weight, and duration of previous treatment with dulaglutide.

The change in treatment from dulaglutide to semaglutide was made for clinical reasons. The reasons for changing were insufficient HbA1c reduction (considered insufficient when it was < 1% 6 mo into therapy), need for greater weight loss (considered insufficient when 6 mo into therapy weight loss had been < 3%), or GI intolerance to dulaglutide. Three groups of patients were established based on this reason to analyze whether there were any differences between them: group 1 (G1), in which the reason for changing was insufficient efficacy in HbA1c reduction; group 2 (G2), due to a need for greater weight loss; and group 3 (G3), due to intolerance to the previous drug.

We conducted a comparative analysis of changes in HbA1c and weight with respect to the start of treatment, which were evaluated 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo after therapeutic change. Adverse effects were also recorded at the follow-up.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using SPSS-24 for paired data and repeated measures. Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), considering statistical significance when p < 0.05.

Ethical considerationsThis study was conducted in full compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient approval was obtained at the time of the change, and data confidentiality was maintained during the collection and analysis of the study data.

ResultsPatients’ baseline characteristicsA total of 123 patients with T2DM and obesity (66 men and 57 women) were included in the analysis, whose treatment was switched from weekly SC dulaglutide to weekly SC semaglutide. Most changes (82.4%) were due to insufficient efficacy in HbA1c reduction. GI intolerance (10.4%) or need for greater weight loss (7.2%) were, in order of frequency, other reasons for the change in treatment.

In the analyzed patient group, mean age was 62 years, with a mean BMI of 37 kg/m2 and a mean duration of diabetes of 11.5 years (Table 1). Regarding concomitant treatment, 77.2% were on metformin, 42.3% on iSGLT2, and 50.4% on insulin.

Treatment efficacyChanges in mean HbA1cPrior to initiating dulaglutide, the sample presented a baseline HbA1c value of 8.43 ± 1.54%. Treatment with dulaglutide showed a mean HbA1c reduction of -0.38% (p = 0.003) during a mean treatment period of 16.9 ± 13.8 mo (Table 2).

In relation to treatment with semaglutide, the baseline HbA1c value was 7.99 ± 1.32%. After switching to semaglutide, an additional reduction in HbA1c levels was observed at 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo: −0.43% (p = 0.000), −0.54% (p = 0.000), −0.38% (p = 0.021), and −0.12% (p = 0.622), respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 2).

Prior to initiating dulaglutide, the baseline weight was 101.59 ± 17.72 kg. With dulaglutide, a mean weight loss of −1.3 kg (p = 0.003) was recorded during the mean treatment period of 16.9 ± 13.8 mo (Table 2).

Prior to switching to semaglutide, the baseline weight was 100.59 ± 17.68 kg. After switching to semaglutide, an additional and greater size of weight reduction was evident at 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo: −2.7 kg (p = 0.000), −3.7 kg (p = 0.000), −5.4 kg (p = 0.001), and −4.2 kg (p = 0.000), respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 2).

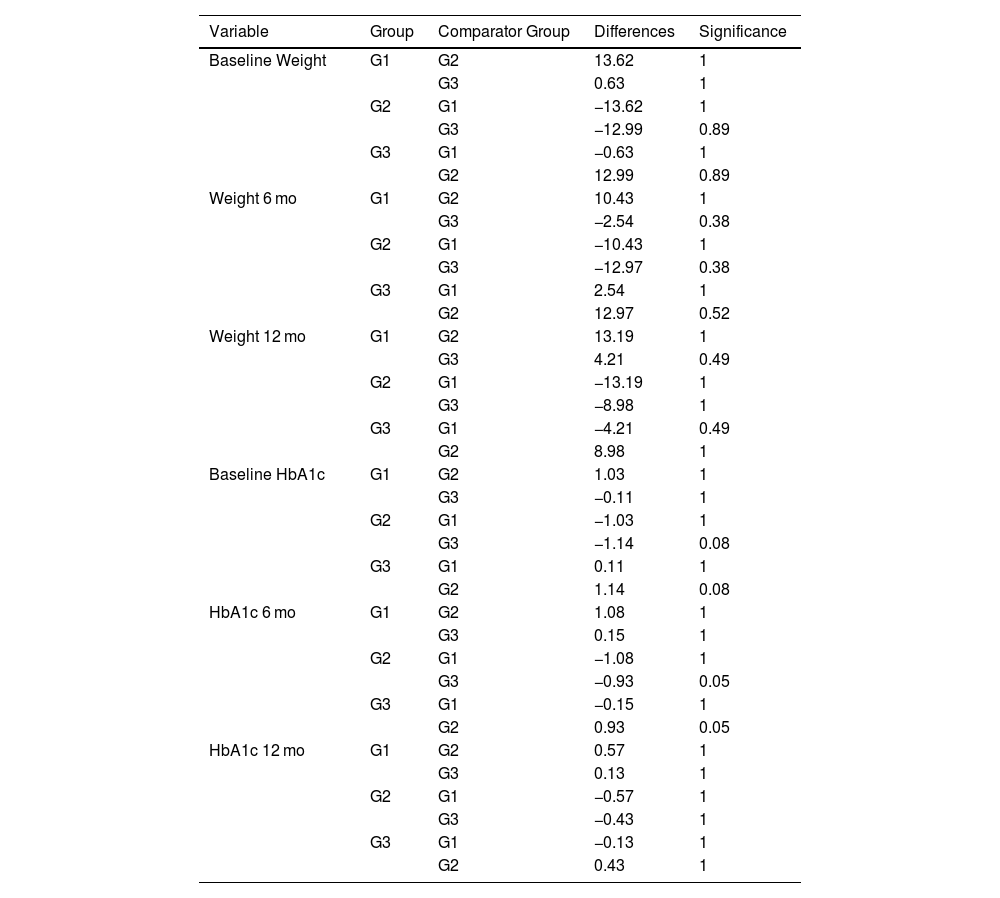

Evaluation based on the reason for changingOf all 123 patients selected for the study, information on the reason for changing was available for 113 of them. In 82.31% switch to semaglutide was due to insufficient efficacy (G1), in 7.96% due to the need for greater weight loss (G2), and in 9.73% due to intolerance (G3). We conducted a comparative analysis of changes in HbA1c and weight with respect to the start of treatment, which were evaluated at 6 and 12 mo. When conducting the subgroup analysis, no significant differences were found based on the reason for the treatment change in HbA1c reduction and weight loss (Table 4).

Changes in weight and HbA1c according to the reason for changing.

| Variable | Group | Comparator Group | Differences | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Weight | G1 | G2 | 13.62 | 1 |

| G3 | 0.63 | 1 | ||

| G2 | G1 | −13.62 | 1 | |

| G3 | −12.99 | 0.89 | ||

| G3 | G1 | −0.63 | 1 | |

| G2 | 12.99 | 0.89 | ||

| Weight 6 mo | G1 | G2 | 10.43 | 1 |

| G3 | −2.54 | 0.38 | ||

| G2 | G1 | −10.43 | 1 | |

| G3 | −12.97 | 0.38 | ||

| G3 | G1 | 2.54 | 1 | |

| G2 | 12.97 | 0.52 | ||

| Weight 12 mo | G1 | G2 | 13.19 | 1 |

| G3 | 4.21 | 0.49 | ||

| G2 | G1 | −13.19 | 1 | |

| G3 | −8.98 | 1 | ||

| G3 | G1 | −4.21 | 0.49 | |

| G2 | 8.98 | 1 | ||

| Baseline HbA1c | G1 | G2 | 1.03 | 1 |

| G3 | −0.11 | 1 | ||

| G2 | G1 | −1.03 | 1 | |

| G3 | −1.14 | 0.08 | ||

| G3 | G1 | 0.11 | 1 | |

| G2 | 1.14 | 0.08 | ||

| HbA1c 6 mo | G1 | G2 | 1.08 | 1 |

| G3 | 0.15 | 1 | ||

| G2 | G1 | −1.08 | 1 | |

| G3 | −0.93 | 0.05 | ||

| G3 | G1 | −0.15 | 1 | |

| G2 | 0.93 | 0.05 | ||

| HbA1c 12 mo | G1 | G2 | 0.57 | 1 |

| G3 | 0.13 | 1 | ||

| G2 | G1 | −0.57 | 1 | |

| G3 | −0.43 | 1 | ||

| G3 | G1 | −0.13 | 1 | |

| G2 | 0.43 | 1 |

G1: group 1; G2: group 2; G3: group 3; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin.

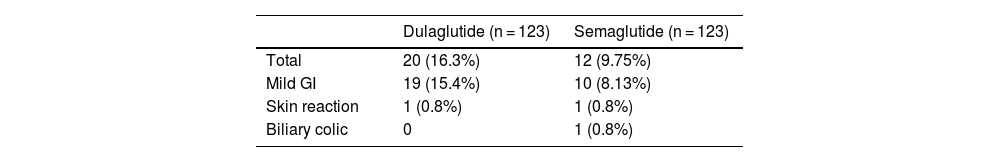

While on dulaglutide, 20 adverse effects were recorded, predominantly mild (19 GI events and 1 mild skin reaction). After switching to semaglutide, 12 adverse effects were observed, mostly mild GI events and 1 mild skin reaction, in addition to 1 case of biliary colic. In 9 patients, treatment with semaglutide was discontinued, mainly due to preference for the previous device, mild GI events, or lack of response (Table 5).

DiscussionThe main aim of the study was to analyze, under real-world conditions, the safety (occurrence of adverse events) and efficacy profile (measured as additional reduction in HbA1c and weight) of switching from dulaglutide to semaglutide. Based on the results obtained in REWIND,15 in which weekly SC dulaglutide was associated with a mean HbA1c reduction of −0.6% and a weight loss of −1.46 kg vs placebo, a decision was made to avoid including patients who had switched from other GLP-1 RAs different than dulaglutide, as it was the second most potent analog at the time data were collected. There are no previous studies of switching from dulaglutide to semaglutide under real-world conditions, but there are with other GLP-1 RAs. This is a differential aspect of this observational study vs others published. Our previous results with dulaglutide (Table 2) were slightly lower than those observed in REWIND,15 especially in HbA1c reduction, which could be justified by the inclusion bias of analyzing only patients in whom a GLP-1 switch was made due to poor previous response. In most patients, the switch was made due to insufficient efficacy in terms of HbA1c reduction (82.31%).

In Spain, several former studies have evaluated the efficacy of GLP-1 RAs in real-world settings.24–27 The observational study by Gorgojo-Martínez et al.25 in patients with T2DM under real-world conditions evaluated the efficacy profile of SC exenatide twice daily (n = 116) vs SC liraglutide once daily (n = 162) over a period of 52 weeks. There was a significant reduction in both HbA1c (approximately 0.5%) and weight (loss around 6–8 kg) in each of the groups.

Another subsequent observational study evaluated the differences in real-world effectiveness of different GLP-1 RAs (daily SC exenatide, daily SC lixisenatide, daily SC liraglutide, weekly SC dulaglutide).26 This study analyzed all prescriptions made between 2009 and 2016 for GLP-1 RAs with a total sample of 735 and a follow-up of 39 mo. During this study, a very small number of treatment changes occurred between GLP-1 RAs (n = 47, 6.39%), with most of these changes being from exenatide to liraglutide (n = 24, 22% of all changes).

In another retrospective study, conducted in our setting with a larger population (n = 4,242), from a sample of patients with T2DM from primary care centers in Catalonia who started treatment with GLP-1 RAs (lixisenatide, exenatide, and liraglutide) from 2007 through 2014, changes in weight and HbA1c were analyzed 6 and 12 mo into therapy. A mean HbA1c reduction of −1% and a mean weight loss of 3.6 kg were recorded, which are results similar to those observed in randomized clinical trials.27

In 2021, the SWITCH-SEMA 1 study was initiated, with results published in 2023. This is a multicenter, prospective, randomized, and blinded study whose main objective is to compare the effects of semaglutide with those of liraglutide and dulaglutide. A total of 100 patients with T2DM on liraglutide (group A) 0.9 to 1.8 mg/day or dulaglutide (group B) 0.75 mg/weekly for more than 12 weeks and who had HbA1c levels between 6 and 9.9% and a BMI ≥ 22 kg/m2 were selected. They were randomized to continue with their GLP-1 RA or switch to weekly subcutaneous semaglutide for 24 weeks.

HbA1c levels were significantly reduced in both groups. In group A: 7.8% ± 1.0% to 7.8% ± 0.7% (liraglutide) vs 7.9% ± 0.7% to 7.3% ± 0.7% (semaglutide). In group B: 7.8% ± 1.0% to 7.9% ± 1.2% (dulaglutide) vs 7.8% ± 0.8% to 7.1% ± 0.6% (semaglutide).

Therefore, although it differs in many points in terms of design with respect to our study, it supports the results.28

Therefore, reviewing the studies published to date, there is a limited number of comparative studies between GLP-1 RAs, and even fewer that analyze the effects of switching between them. Furthermore, among the studies that have evaluated the effects of switching between GLP-1 RAs, most started with initial treatment with daily administered GLP-1 RAs. In this regard, our study is the only one that provides real-world data comparing the 2 most effective weekly administered GLP-1 RAs.

Real-world studies are necessary to confirm that the results obtained in clinical trials, which are conducted with very strict inclusion criteria, often do not include the variety of patients with T2DM and obesity followed in daily clinical practice. If our data are compared with those of SUSTAIN-7, results are very similar. In SUSTAIN-7, an additional HbA1c reduction of −0.41% (95% CI, −0.57% to −0.25%; p < 0.0001) and weight loss of −3.55 kg (95% CI, −4.32 kg to −2.78 kg; p < 0.0001) were observed vs dulaglutide 1.5 mg.13 In our study, an additional reduction in HbA1c levels was observed at 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo: −0.43% (p = 0.000), −0.54% (p = 0.000), −0.38% (p = 0.021), and −0.12% (p = 0.622), respectively, and an additional and greater size of weight reduction at 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo: −2.7 kg (p = 0.000), −3.7 kg (p = 0.000), −5.4 kg (p = 0.001), and −4.2 kg (p = 0.000), respectively. Of note, in SUSTAIN-7 data are from a 9-mo follow-up, and in our study the analysis was performed at 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo (with a smaller sample in the later months of follow-up, which may have affected the statistical significance of those results).

In our work, after analyzing the main objective, a subgroup analysis was performed to determine whether there were any differences based on the reason for change in HbA1c reduction and weight loss across the different groups. Groups were established based on the reason that triggered the switch from dulaglutide to semaglutide: in group 1, those in whom an additional HbA1c reduction was sought (G1, 82.31%); in group 2, those whose goal was greater weight loss (G2, 7.96%); and in group 3, patients who had not tolerated the previous treatment with dulaglutide well (G3, 9.73%).

When performing the subgroup analysis based on the reason for changing, we observed a greater reduction in HbA1c and greater weight loss, at least numerically, when the change was made seeking greater weight loss (G2). However, these differences did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.38 and p = 0.52 at 6 mo and p = 0.49 and p = 1 at 12 mo), probably due to the number of patients included in the sample (Table 4).

Regarding adverse effects, in contrast to what was observed in SUSTAIN-7, in our study the switch from dulaglutide to semaglutide was not associated with a significant increase in the rate of GI adverse effects, with even more events observed with the previous treatment with dulaglutide, which could be explained by the fact that one of the reasons for making the GLP-1 RA switch was previous intolerance or poor adherence to dulaglutide.

This study has some limitations, which are discussed below. It is a retrospective study and was conducted at a single center. Another additional limitation was the small number of patients included, as only those who switched from dulaglutide to semaglutide were analyzed. This circumstance, a priori, had an impact on the number of patients who could potentially have been included in the study. On the other hand, many of the patients who started treatment with SC semaglutide could not be included in our study because they were previously on a different GLP-1 RA (daily or weekly) or because they had started treatment with a GLP-1 RA for the first time.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that switching from weekly SC dulaglutide to weekly SC semaglutide may be advisable, regardless of the reason for changing. These results confirm a greater reduction in HbA1c and weight, which is desirable in people with T2DM and obesity. However, more studies with a larger number of patients are needed to confirm and reinforce the results of this study. Real-world studies are relevant and should confirm the safety and efficacy profile of new drugs from phase II-III clinical trials in the context of routine clinical practice.

ConclusionsThe SEMA-SWITCH study demonstrated that the transition from weekly SC dulaglutide to weekly SC semaglutide is associated with an additional reduction in both HbA1c levels and body weight, without significant changes in the rate of adverse effects. Furthermore, these benefits occurred regardless of the reason for changing due to insufficient efficacy, the need for greater weight reduction, or previous intolerance to weekly SC dulaglutide. These findings support switching between GLP-1 RAs as a good therapeutic option when the previous treatment has a lower than expected efficacy or there are adverse effects that limit its use.

FundingNone declared.

The authors Felipe Pardo Lozano, Arantxa Rubio Marcos, Rosa Casañ Fernandez, Amparo Bartual Rodrigo, and Francisco Javier Ampudia-Blasco have participated in presentations on drugs for the treatment of diabetes and for weight loss in obesity. Dr. Sergio Martinez-Hervas has not collaborated with any laboratory that has products for the treatment of obesity.