To evaluate the achievement of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLc) goals established by the 2019 European Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemias and 2021 Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Guidelines, describe the lipid-lowering treatment received, analyze the achievement of goals according to the lipid-lowering treatment received and study the factors associated with therapeutic success.

DesignObservational study that included 185 patients of both sexes aged 18 or over undergoing lipid-lowering treatment for primary or secondary prevention, attended at the Lipid Unit.

Results62,1% of the patients had a very high cardiovascular risk (CVR) according to the 2019 guidelines, and 60,5% according to the 2021 guidelines. Of the total cases, 22,7% achieved adequate control of LDLc according to the 2019 guidelines and 20% according to the 2021 guidelines. 47,6% of the patients received very high intensity lipid-lowering treatment, and 14,1% received extremely high intensity lipid-lowering treatment. 76% of subjects with very high CVR on extremely high intensity lipid-lowering treatment achieved the therapeutic objectives of both guides. In the multivariate analysis, factors associated with therapeutic success were the presence of arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease, the intensity of lipid-lowering treatment, diabetes mellitus, and low to moderate alcohol consumption.

ConclusionsDyslipidemia control is improvable. High or extremely high intensity lipid-lowering treatments can contribute to optimizing control of patients with higher CVR.

Evaluar la consecución de los objetivos de colesterol unido a lipoproteínas de baja densidad (cLDL) establecidos por las guías europeas de manejo de las dislipemias de 2019 y de prevención cardiovascular de 2021, describir el tratamiento hipolipemiante realizado, analizar el logro de los objetivos según el tratamiento hipolipemiante recibido y estudiar los factores asociados al éxito terapéutico.

DiseñoEstudio observacional con 185 pacientes de ambos sexos de 18 años o más en tratamiento hipolipemiante para prevención primaria o secundaria, atendidos en la Unidad de Lípidos.

ResultadosEl 62,1% de los pacientes presentó un riesgo cardiovascular (RCV) muy alto según la guía de 2019, y el 60,5% según la de 2021. Del total de casos, el 22,7% logró un control adecuado del cLDL según la guía de 2019 y el 20% lo hizo de acuerdo con la de 2021. El 47,6% de los pacientes recibió tratamiento hipolipemiante de muy alta intensidad y el 14,1% lo recibió de extremadamente alta intensidad. El 76% de los sujetos con muy alto RCV en tratamiento hipolipemiante de extremadamente alta intensidad logró los objetivos terapéuticos de ambas guías. En el análisis multivariante, los factores asociados al éxito terapéutico fueron la presencia de enfermedad cardiovascular arteriosclerótica, la intensidad del tratamiento hipolipemiante, la diabetes mellitus y el consumo bajo o moderado de alcohol.

ConclusionesEl control de la dislipemia es mejorable. Los tratamientos hipolipemiantes de alta o extremadamente alta intensidad pueden contribuir a optimizar el control de los pacientes con mayor RCV.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the main cause of morbidity and mortality in Europe.1 Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is the main promoter of atherogenesis2 and is the third modifiable risk factor for CVD.3 There is evidence that indicates that reducing LDL-C levels is related to a significant decrease in the risk of developing CVD, regardless of the type of medications used.4–11 The evidence to date suggests that the lower the LDL-C, the greater the significant reduction in cardiovascular events, without entailing harmful effects.12,13 For this reason, the reduction of LDL-C is incorporated into the European guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia14 and the prevention of CVD.15 These guidelines recommend that treatment goals be established based on patients' overall cardiovascular risk (CVR) level.

During recent years, the degree of control of dyslipidemia has improved in keeping with European guidelines.14,15 However, different studies, both European16–19 and Spanish,20–24 have shown that the level of control is still insufficient.

The main objective of this study is to evaluate the degree of achievement of LDL-C objectives according to European guidelines.14,15 Furthermore, the study aims to describe the lipid-lowering treatment performed based on the CVR categories and the percentage of achievement of LDL-C objectives according to the lipid-lowering treatment received and study the factors associated with therapeutic success.

Material and methodsStudy designThis is a retrospective observational study that included patients of both sexes aged 18 years or older, who received stable lipid-lowering treatment with statins, ezetimibe and/or proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors (PCSK9i) for primary or secondary prevention. Lipid-lowering treatment was defined as stable when there were no changes in the therapeutic regimen or dose at least 28 days before LDL-C measurement. Uncontrolled hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, dialysis, chronic liver disease, cancer, and dyslipidemia secondary to drugs or pregnancy were established as exclusion criteria.

Information was collected from the computerized medical history (CMH) of the patients of the Lipid Unit of the Hospital de Figueras visited in the last 12 months as of 03/24/2022. This clinical unit, made up of a responsible doctor and a nurse, with access to a dietician, provides coverage to the Alt Empordá region, with a census population of 144,926 inhabitants in the year 2022.25 The patients came from both primary and specialised care.

The primary objective was defined by the proportion of patients on stable lipid-lowering therapy for primary or secondary prevention who achieved the LDL-C target according to European guidelines.14,15 The last LDL-C value (mg/dL) of each patient was used to establish the degree of control. In addition, the baseline LDL-C recorded at the patient's first visit to the Lipid Unit was used to calculate LDL-C reduction.

Secondary objectives were to describe lipid-lowering treatment according to CVR categories and to assess the degree of achievement of LDL-C targets according to European guidelines14,15 in relation to the lipid-lowering treatment received, as well as to identify factors associated with the achievement of therapeutic LDL-C targets.

The lipid-lowering treatment of each patient was classified according to the percentage of LDL-C reduction expected, in accordance with the categories proposed by Masana et al.26: low intensity (<30%), moderate intensity (≥30% and <50%), high intensity (≥50% and <60%), very high intensity (≥60% and <80%) and extremely high intensity (≥80% and <85%).

Through the CMV, data were collected on the following variables: age, sex, anthropometric characteristics [including weight, height, body mass index (BMI) and abdominal perimeter], smoking [according to the document recently published by the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis (SEA for its initials in Spanish)27: current smoker (person who has smoked at least one cigarette in the last 6 months), never smoker (person who has never smoked or has smoked<100 cigarettes in a lifetime) and ex-smoker (person who having been a smoker has been completely abstinent for at least the last 6 months)], alcohol consumption [non-drinker, low/moderate consumption (<30g/day in women; <40g/day in male), high consumption (≥30g/day in female; ≥40g/day in male); for the multivariate study this variable was re-coded into drinking or not drinking]; presence or absence of hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM) [DM<10 years without other cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF) or target organ damage (TOD), DM≥10 years or other CVRF and without TOD, DM with non-severe TOD, DM with severe TOD],14,15 moderate or severe chronic kidney disease (CKD),14,15 familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) with or without CVRF and clinical or documented atherosclerotic CVD [coronary heart disease (CHD), ischaemic stroke (CVA) or peripheral artery disease (PAD)]; and the value (%) of the European low-risk CVR charts in apparently healthy patients (SCORE and SCORE2 or SCORE2-OP).14,15

In addition, the following laboratory values were recorded from the last laboratory control: total cholesterol, LDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), non-HDL-C, triglycerides, lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] and glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), urine albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR).

Statistical analysisThe statistical study was carried out using the SPSS Windows software, version 25.0 (IBM). Categorical variables were described by the absolute value of the frequency and its percentage. Continuous variables were described by the mean and standard deviation (SD). The study of the association of categorical variables was performed using the Chi-square test. When the variables were continuous, the Student's t-test was used for the comparison of two independent groups.

On the other hand, the multivariate study was carried out by logistic regression using the Wald forward stepwise method, with the dichotomous variable “achievement of LDL-C targets” as the dependent variable and allowing the following independent variables to be selected by the model: sex, age, smoking, alcohol consumption, HT, DM, CKD, atherosclerotic CVD and the intensity of lipid-lowering treatment.

Ethical considerationsThis was an observational, non-interventional study in which patient data were collected without interfering with routine clinical practice. To guarantee the confidentiality of the patients' personal information, it was carried out using a pseudo-anonymised database. The copy with the correlation “Identifier code - Personal identification data” was only available to the Research Secretariat, which was the custodian of the file.

The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Doctor Josep Trueta.

ResultsDuring the study period, 242 patients were followed up by the Lipid Unit of the Hospital de Figueras, of whom 185 met the inclusion criteria and none the exclusion criteria.

Of the patients included in the study, 115 (62.1%) had a very high CVR, 49 (26.5%) a high CVR, 12 (6.5%) a moderate CVR and 9 (4.9%) a low CVR, according to the classification of CVR of the dyslipidaemia management guidelines 201914. According to the RCV classification of the prevention guideline 2021,15 the RCV in 112 (60.5%) was very high, in 62 (33.6%) high and in 11 (5.9%) low-moderate.

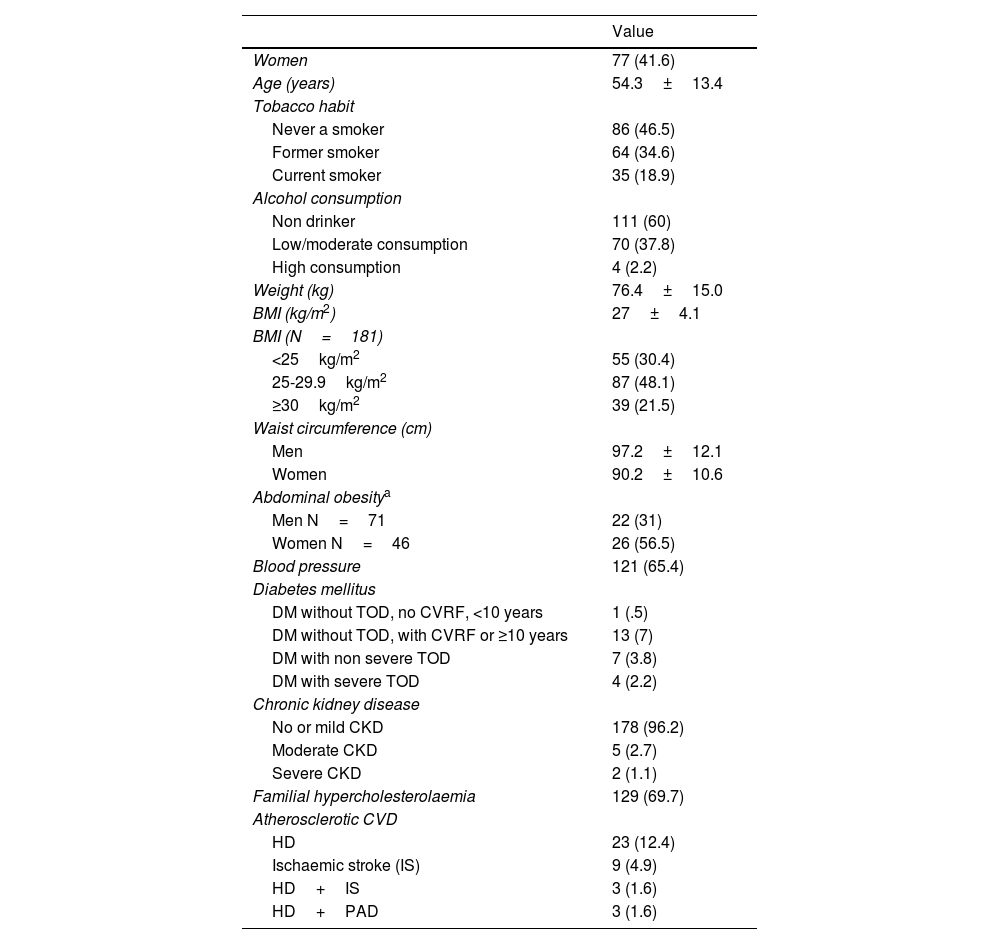

According to Table 1, the mean age was 54.3 years (SD 13.4), with a slight predominance of men (58.4%). A high prevalence of CVRF was observed and a large percentage of patients (69.7%) had FH. This would explain the high proportion of subjects with a high or very high CVR according to the 201914 guidelines (88.6%) and the 202115 guidelines (94.1%).

Main demographic, anthropometric and clinical characteristics of the 185 patients.

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Women | 77 (41.6) |

| Age (years) | 54.3±13.4 |

| Tobacco habit | |

| Never a smoker | 86 (46.5) |

| Former smoker | 64 (34.6) |

| Current smoker | 35 (18.9) |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| Non drinker | 111 (60) |

| Low/moderate consumption | 70 (37.8) |

| High consumption | 4 (2.2) |

| Weight (kg) | 76.4±15.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27±4.1 |

| BMI (N=181) | |

| <25kg/m2 | 55 (30.4) |

| 25-29.9kg/m2 | 87 (48.1) |

| ≥30kg/m2 | 39 (21.5) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | |

| Men | 97.2±12.1 |

| Women | 90.2±10.6 |

| Abdominal obesitya | |

| Men N=71 | 22 (31) |

| Women N=46 | 26 (56.5) |

| Blood pressure | 121 (65.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| DM without TOD, no CVRF, <10 years | 1 (.5) |

| DM without TOD, with CVRF or ≥10 years | 13 (7) |

| DM with non severe TOD | 7 (3.8) |

| DM with severe TOD | 4 (2.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease | |

| No or mild CKD | 178 (96.2) |

| Moderate CKD | 5 (2.7) |

| Severe CKD | 2 (1.1) |

| Familial hypercholesterolaemia | 129 (69.7) |

| Atherosclerotic CVD | |

| HD | 23 (12.4) |

| Ischaemic stroke (IS) | 9 (4.9) |

| HD+IS | 3 (1.6) |

| HD+PAD | 3 (1.6) |

Values are expressed as n (%) or mean±standard deviation.

BMI: Body Mass Index; CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; CVD: Cardiovascular Disease; CVRF: Cardiovascular risk factors; DM: Diabetes Mellitus; HD: Heart Disease; IS: Ischaemic Stroke; PAD: Peripheral Arterial Disease; TOD: Target Organ Damage.

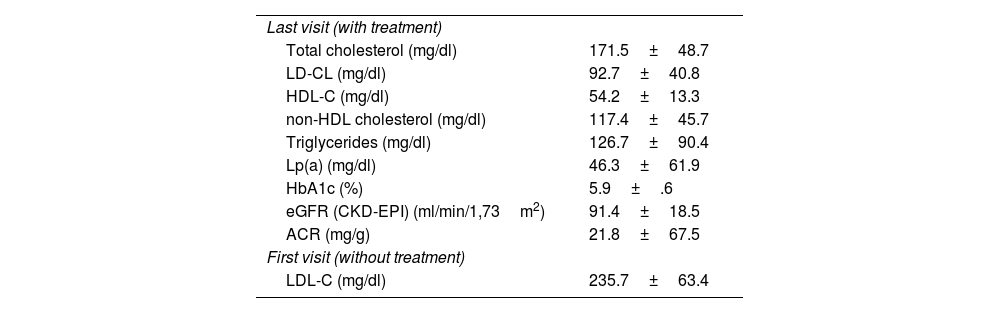

The analytical values of the whole sample (Table 2) showed a mean LDL-C of 92.7mg/dl (SD 40.8) at the last visit (with lipid-lowering treatment) and a mean baseline LDL-C of 235.7mg/dl (SD 63.4). This indicates that lipid-lowering treatment achieved a mean LDL-C reduction of 143mg/dl (SD 75.8), i.e., 57.87%.

Laboratory data from the last visit and baseline LDL-C.

| Last visit (with treatment) | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 171.5±48.7 |

| LD-CL (mg/dl) | 92.7±40.8 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 54.2±13.3 |

| non-HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 117.4±45.7 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 126.7±90.4 |

| Lp(a) (mg/dl) | 46.3±61.9 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.9±.6 |

| eGFR (CKD-EPI) (ml/min/1,73m2) | 91.4±18.5 |

| ACR (mg/g) | 21.8±67.5 |

| First visit (without treatment) | |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 235.7±63.4 |

Values are expressed as mean±standard deviation.

ACR: Urine albumin creatine ratio; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c: Glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a): Lipoprotein (a).

Based on CVR classification, 22.7% of the total sample had adequate LDL-C control according to the 201914 guidelines, while 20% had adequate LDL-C control according to the 202115 guidelines.

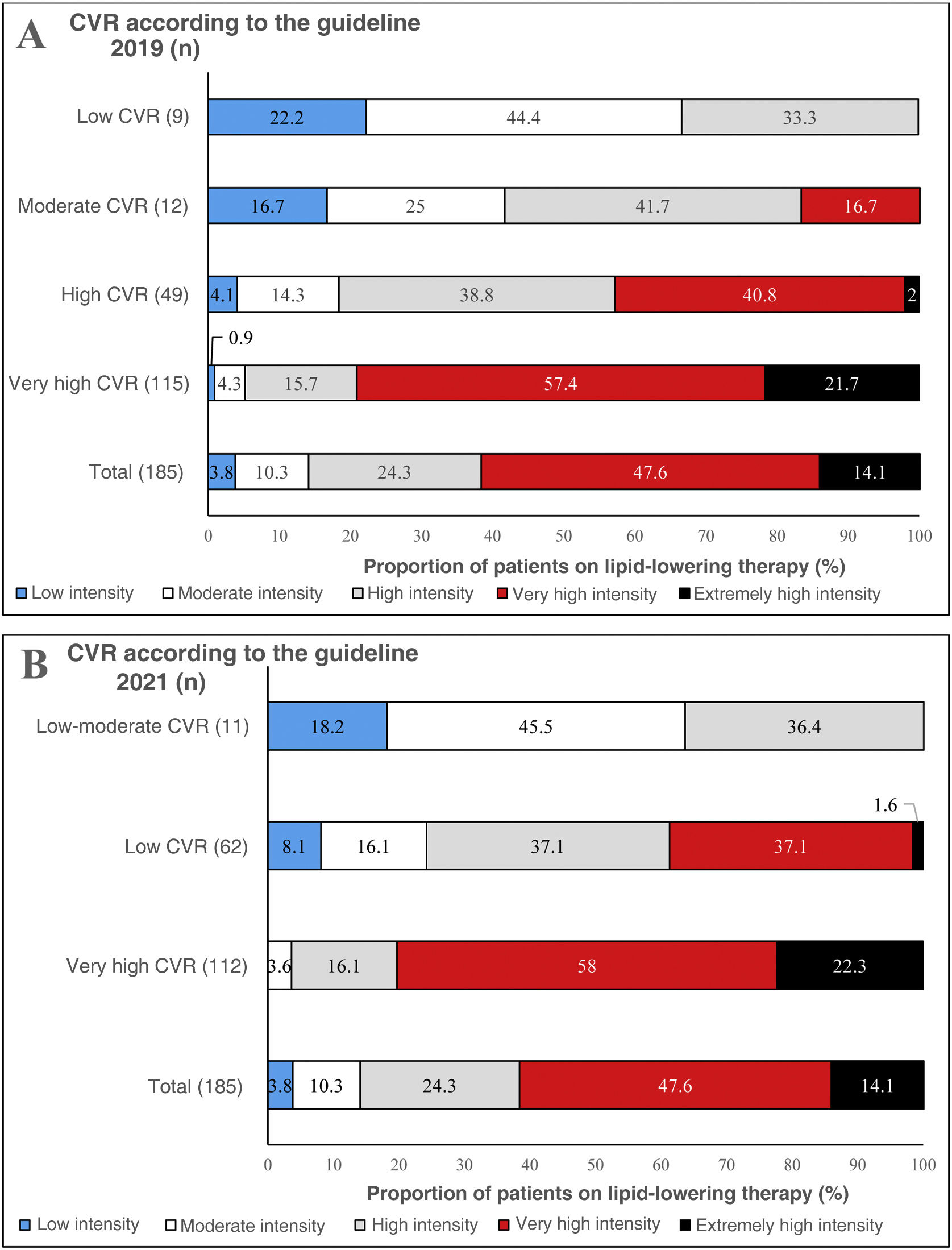

Fig. 1A and B shows the intensity of lipid-lowering treatment undertaken by subjects according to CVR, according to the 2019 and 2021 European guidelines, respectively. Respectivamente.14,15 Overall, 47.6% of patients received very high intensity lipid-lowering treatment, while 14.1% received extremely high intensity lipid-lowering treatment. Patients with very high CVR according to the 201914 guidelines received 21.7% extremely high-intensity lipid-lowering therapy and 57.4% very high-intensity lipid-lowering therapy (Fig. 1A), while patients with very high CVR according to the 202115 guidelines received 22.3% extremely high-intensity lipid-lowering therapy and 58% very high-intensity lipid-lowering therapy (Fig. 1B). Patients with high CVR according to the 201914 and 202115 guidelines received mainly high and very high intensity lipid-lowering therapy (Figs. 1A and B).

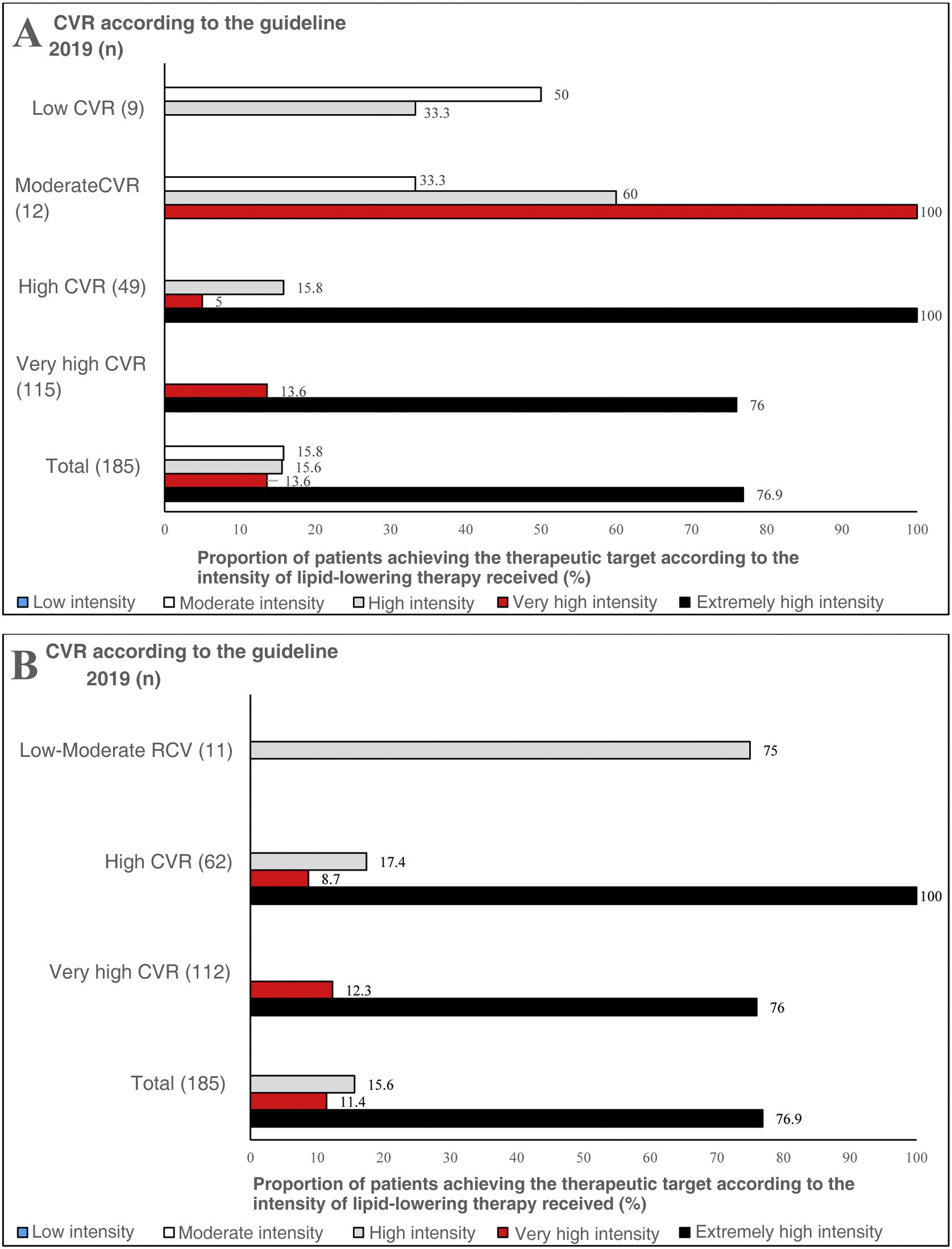

According to the 201914 guidelines, 100% of patients with moderate CVR receiving very high-intensity lipid-lowering therapy achieved therapeutic LDL-C targets (Fig. 2, Fig. 2A). On the other hand, according to the 202115 guidelines, 75% of patients with low-moderate CVR who were on high-intensity treatment achieved optimal LDL-C control (Fig. 2B). Similarly, 100% of subjects with high CVR and 76% of those with very high CVR receiving extremely high-intensity lipid-lowering therapy achieved the lipid control target set in both the 201914 guidelines and the 202115 guidelines (Figs. 2A and B).

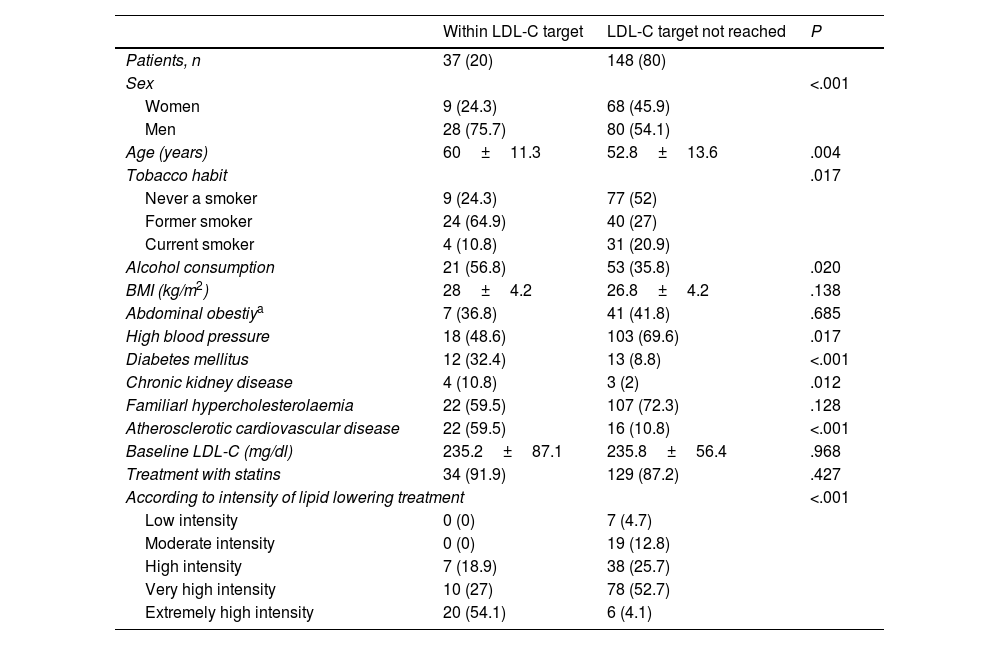

Table 3 details the factors associated with good lipid control according to STEP 2 of the 2021 European guidelines. These include male sex, being an ex-smoker, alcohol consumption, DM, atherosclerotic CVD and receiving extremely high intensity lipid lowering treatment. In contrast, HTN is associated with poor control.

Factors associated with good lipid control (achievement of therapeutic LDL-C targets according to STEP 2 of the 2021 European guideline).

| Within LDL-C target | LDL-C target not reached | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 37 (20) | 148 (80) | |

| Sex | <.001 | ||

| Women | 9 (24.3) | 68 (45.9) | |

| Men | 28 (75.7) | 80 (54.1) | |

| Age (years) | 60±11.3 | 52.8±13.6 | .004 |

| Tobacco habit | .017 | ||

| Never a smoker | 9 (24.3) | 77 (52) | |

| Former smoker | 24 (64.9) | 40 (27) | |

| Current smoker | 4 (10.8) | 31 (20.9) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 21 (56.8) | 53 (35.8) | .020 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28±4.2 | 26.8±4.2 | .138 |

| Abdominal obestiya | 7 (36.8) | 41 (41.8) | .685 |

| High blood pressure | 18 (48.6) | 103 (69.6) | .017 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (32.4) | 13 (8.8) | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (10.8) | 3 (2) | .012 |

| Familiarl hypercholesterolaemia | 22 (59.5) | 107 (72.3) | .128 |

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease | 22 (59.5) | 16 (10.8) | <.001 |

| Baseline LDL-C (mg/dl) | 235.2±87.1 | 235.8±56.4 | .968 |

| Treatment with statins | 34 (91.9) | 129 (87.2) | .427 |

| According to intensity of lipid lowering treatment | <.001 | ||

| Low intensity | 0 (0) | 7 (4.7) | |

| Moderate intensity | 0 (0) | 19 (12.8) | |

| High intensity | 7 (18.9) | 38 (25.7) | |

| Very high intensity | 10 (27) | 78 (52.7) | |

| Extremely high intensity | 20 (54.1) | 6 (4.1) | |

Values are expressed as n (%) or mean±±standard deviation.

BMI: Body Mass Index; LDL-C: Low density lipoprotein cholesterol.

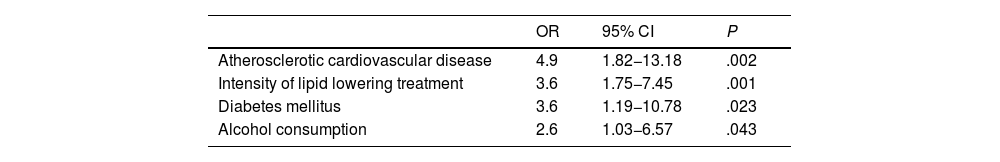

In the multivariate analysis, the factors associated with good lipid control that entered the logistic regression model were, in this order at each step, the presence of atherosclerotic CVD, followed by the intensity of lipid lowering treatment received, DM and finally moderate alcohol consumption (Table 4).

Factors independently associated with good lipid control (achievement of therapeutic LDL-C targets according to STEP 2 of the European guidelines 2021). Logistic regression by the Wald forward stepwise method.

| OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease | 4.9 | 1.82−13.18 | .002 |

| Intensity of lipid lowering treatment | 3.6 | 1.75−7.45 | .001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.6 | 1.19−10.78 | .023 |

| Alcohol consumption | 2.6 | 1.03−6.57 | .043 |

95% CI: 95% Confidence Interval; LDL-C: Low density lipoprotein cholesterol; OR: Odds Ratio.

The ULFI study is one of the first to evaluate the efficacy of achieving therapeutic LDL-C targets, taking into account the recommendations of the 201914 European guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemia and the 202115 guidelines for the prevention of CVD in daily clinical practice. The results of this study add to the numerous observational and cross-sectional studies that have analysed the degree of compliance with therapeutic targets applying the above guidelines. Of the total number of patients in the sample, only 22.7% met the lipid control targets according to the 201914 guidelines and 20% according to the 202115 guidelines. The results of this study show that there is an opportunity for improvement in lipid control in our healthcare area.

The results obtained by us are lower than those found by Morales al.20 in dyslipidaemic patients seen in lipid and vascular risk units of the Xarxa d'Unitats de Lípids i Arteriosclerosi de Catalunya (XULA), and in the REPAR21 study of patients with very high CVR referred to cardiology clinics in Spain. In both cases, the percentage of patients achieving the therapeutic LDL-C target, according to the 201228 European CVD prevention guidelines, was 28% and 26%, respectively. However, these guidelines set less stringent treatment targets than those recommended by the current guidelines

The EDICONSIS-ULISEA22 study showed that patients with dyslipidaemia and CVR referred to SEA-accredited lipid units had a good overall LDL-C control of 44.7%, a higher percentage than that found in our study. However, the EDICONSIS-ULISEA22 study considered the lipid control targets of the 200729 European CVD prevention guidelines, which were laxer than the current ones. When considering the therapeutic targets of the 201228 guidelines, the percentage of patients meeting the targets was 17.9% and 16.5% for patients with established CVD or DM, respectively. These figures are closer to those found in our study, because a large proportion of patients had a high (33.51%) or very high (60.54%) CVR.

Our results are far from those recently published from the SEA Dyslipidaemia Registry by Marco-Benedí et al.23 in subjects in primary or secondary prevention with non-HF hypercholesterolaemia. These results showed that 47.7% of subjects in secondary prevention reached the LDL-C targets set by the 2016,30 European dyslipidaemia management guideline, of LDL-C<70mg/dl. This is in line with the results observed in Spain from the European EUROASPIRE V16 cohort of very high CVR patients (49%). Similar results to those observed in the observational DYSIS II study conducted in 7 European countries, where 30.9% of patients with acute coronary syndrome who had previously received statins had a LDL-C<70mg/dl at 4-month follow-up, compared to 41.5% of those who had not received statins prior to the acute episode.17 However, these targets differ from those set by the latest European guidelines europees14,15 used in our study, recommending LDL-C<<55mg/dl for subjects in secondary prevention.

Using the same therapeutic LDL-C targets as we did, Aneri et al.24 found that 14.8% of patients in secondary prevention met the targets set in 2019.14 On the other hand, the DA VINCI study18 found that only 33% of patients achieved the targets set in 2019.14 (18% in patients with very high CVR), while the SANTORINI19 found that 20.7% of patients with high and very high CVR achieved them. These results are comparable to those obtained in our study.

The intensity of lipid-lowering treatment we identified was higher than that reported in other observational studies published so far. In the EROMOT20 study, 22.2% and 35.4% were receiving very high intensity and high intensity lipid lowering therapy, respectively. In EUROASPIRE V16 49.9% and 34.1% were receiving high and low-moderate intensity lipid-lowering therapy, respectively. In very high-risk patients (secondary prevention) in the DA VINCI18 study, the most commonly used treatment was moderate-intensity statin monotherapy (43.5%) followed by high-intensity statin monotherapy (37.5%) and marginally combination treatment, 9.3% with ezetimibe and 1.1% with iPCSK9. The results of lipid-lowering treatment intensity in the SANTORINI19 study were more similar to ours, with 25.6% of patients receiving combination therapy (17.5% statin with ezetimibe; 4.7% iPCSK9 with statin and/or ezetimibe). Similarly, in the study published by the SEA Registry,23 the percentage of patients in secondary prevention on high-potency statins at the time of inclusion in the registry was 75%, which is in line with our results. Overall, 14.1%, 47.6% and 24.3% of our sample were receiving extremely high intensity, very high intensity and high intensity lipid-lowering therapy, respectively.

Whereas in EUROASPIRE V16 26.3% and 36.6% of very high CVR patients achieved LDL-C<70mg/dl with low-moderate and high-intensity lipid-lowering therapy, respectively, our study showed that 76% of very high CVR patients receiving extremely high-intensity lipid-lowering treatment achieved a LDL-C<55mg/dl, while 13.6% and 12.3% of those receiving very high-intensity achieved it if classified according to the 201914 or 202115 guidelines, respectively. These results resemble those of the DA VINCI18 study (14% of those treated with low intensity statins, 16% of those treated with moderate intensity, 22% of those treated with high intensity, 20% of those treated with ezetimibe combination and 58% of those receiving iPCSK9 achieved a LDL-C<55mg/dl). Furthermore, the results are similar to those of the SAFEHEART Registry31 of patients with genetically defined FH treated with iPCSK9 (46% of very high-risk and 50% of high-risk patients achieved 2019 LDL-C targets). This is particularly significant given the high proportion of FH patients (69.7%) in our sample.

The factors associated with adequate LDL-C control in our study, such as DM, previous history of atherosclerotic CVD, male sex and more intensive lipid-lowering treatment, are consistent with those found in previous studies.21,22 On the other hand, an association has been observed between active smoking and worse control of LDL-C levels, as in the REPAR study21 and better control in former smokers.

The presence of atherosclerotic CVD was independently associated with higher LDL-C attainment, as demonstrated in the EDICONSIS-ULISEA22 study. The intensity of lipid-lowering therapy was also related to the achievement of the therapeutic target, in agreement with the REPAR,21 DYSIS II17 and SAFEHEART31 registry, which recently revealed that the use of statins in combination with ezetimibe has a positive effect in FH patients treated with iPCSK9. DM was a significant predictor for reaching LDL-C targets in multivariate analysis, in agreement with the REPAR,21 EDICONSIS-ULISEA22 and DYSIS II17 studies. On the other hand, mild-moderate alcohol consumption was independently related to meeting therapeutic LDL-C targets, whereas the REPAR21 study found no such relationship for heavy drinking defined as >2 drinking units per day.

Although our study has the inherent limitations of a cross-sectional design and a small number of patients, it reflects the reality of a Lipid Unit and gives a representative picture of routine clinical practice. Furthermore, this study does not provide information on the specific reasons that could explain the lack of achievement of therapeutic objectives, such as therapeutic inertia, lack of adherence, degree of therapeutic compliance, the proportion of patients intolerant to the different lipid-lowering drugs or the variation in the use of iPCSK9 due to the significant differences in the administrative and prescription limitations of these drugs between the different regions regions.32 Despite concerning a Lipid Unit, which implies knowledge of lipid-lowering treatment and presumed compliance with recommended guidelines, the results found, although positive, show that there is room for improvement. Further research designed to identify the factors involved in the failure to achieve therapeutic targets should therefore be undertaken.

ConclusionsThe results of the ULFI study have shown acceptable control of dyslipidaemia, although there is room for improvement. Achieving LDL-C targets in patients with high and very high CVR requires the use of very high or extremely high intensity lipid-lowering treatments. Atherosclerotic CVD and DM are also related to the achievement of therapeutic LDL-C targets.

FundingThis study was funded thanks to the award obtained n the 1st Research Grant of the Fundació Salut Empordà.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interests to declare relating to this study, none that have impacted the results or interpretation.

Our thanks to Anna Comas, from the Secretaría Técnica de Fundació Salut Empordà, for her invaluable help in refining the data obtained from the computerised medical records.