Clinical studies show that patients at elevated cardiovascular risk are still far from reaching therapeutic targets, especially for LDL-C levels. It is not known whether these patients are managed differently in specialised units than in other settings.

Patients and methodsSixty-one certified lipid units certified in the Dyslipidaemia Registry of the Spanish SVociety of Arteriosclerosis were selected for collection of the study data. We included 3958 subjects >18 years of age who met the criteria of hypercholesterolaemia (LDL cholesterol ≥160mg/dl or non-HDL cholesterol ≥190mg/dl) without familial hypercholesterolaemia. A total of 1665 subjects were studied with a mean follow-up of 4.2 years.

Results and conclusionsA total of 42 subjects had a cardiovascular event since they were included in the Registry, which is .6%. There were no differences in the treatment used at the start of follow-up between subjects with and without a prospective event. LDL-C improved during follow-up but 50% of the patients had not achieved the therapeutic targets at the final follow-up visit. Increased used of high- potency lipid-lowering therapy, including PCSK9 inhibitors, was observed in 16.7% of the subjects with recurrence.

Los estudios clínicos reflejan que los pacientes con riesgo cardiovascular elevado todavía están lejos de alcanzar los objetivos terapéuticos, especialmente de los niveles de cLDL. Se desconoce si el manejo de estos pacientes en unidades especializadas difiere de otros escenarios.

Pacientes y métodosSe seleccionaron 61 Unidades de Lípidos certificadas en el Registro de Dislipemias de la Sociedad Española de Arteriosclerosis para la recogida de datos del estudio. Se incluyeron 3958 sujetos >18 años que cumplían los criterios de hipercolesterolemia (colesterol LDL≥160mg/dl o colesterol no HDL≥190mg/dl) sin hipercolesterolemia familiar. Un total de 1665 sujetos fueron estudiados con un tiempo medio de seguimiento de 4,2 años.

Resultados y conclusionesUn total de 42 sujetos tuvieron un evento cardiovascular desde su inclusión en el Registro, que supone un 0,6%. No hubo diferencias en el tratamiento utilizado al inicio del seguimiento entre los sujetos con y sin evento prospectivo. El cLDL mejoró durante el seguimiento, pero un 50% de los pacientes no alcanzaron los objetivos terapéuticos en la visita final del seguimiento. Se observó un aumento del uso de tratamiento hipolipemiante de alta potencia, incluyendo los inhibidores de PCSK9 en un 16,7% de los sujetos con recurrencias.

Clinical practice studies continue to show that most patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular (CV) disease do not achieve the therapeutic objectives of the main risk factors. The EUROASPIRE V cohort reports that only a third of patients in secondary prevention were within the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) targets set by European guidelines.1 This situation is due, among other reasons, to insufficient intensification of lipid-lowering treatment related to therapeutic inertia, not to mention problems of patient compliance.2

Failure to achieve LDL-C targets is directly related to a higher incidence of recurrence of atheroscleroci CV disease and carries a high economic and social cost.3 There is therefore a need to ensure that healthcare workers and patients themselves make appropriate use of the available therapeutic resources. These include the use of high strength statins in high-risk groups which include individuals with very high LDL-C concentrations; people affected by a serious genetic form of hypercholesterolaemia, such as familial hypsercholesterolaemia (FH) and patients who have already suffered a CV event. In all these subjects the aim is to achieve a decrease in LDL-C of at least > 50%.4

The objectives of this analysis are based on assessing the differences in lipid-lowering treatment in primary and secondary prevention patients seen in a Lipid Unit, including the different lipid-lowering treatment guidelines and their intensity at the time of inclusion in the registry, as well as changes in treatment during follow-up. In addition, secondary objectives were to identify the impact of the diagnosis of CV disease on lipid-lowering treatment regimens and the importance of the type of treatment in the recurrence of CV events.

Patients and methodsThe data for this study were obtained from the Dyslipidaemia Registry of the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis (SEA for initials in Spanish). This is a national, anonymised, multicentre registry in which 61 certified Lipid Units distributed throughout the different autonomous communities of Spain enter information on patients seen in these units with a lipid metabolism disorder.5

Inclusion criteria and data collection were standardised prior to recruitment of cases. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study, and the study protocol complied with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was previously approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragón.

This analysis included all patients over 18 years of age who met with the non-FH hypercholesterolemia criteria. These included patients diagnosed with polygenic hypercholesterolaemia, familial combined hyperlipaemia, dysbetalipoproteinaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia or secondary dyslipaemia with LDL-C ≥ 160mg/dL or non-HDL cholesterol ≥ 190mg/dL. FH was considered to be hypercholesterolaemia with the presence of a pathogenic variant in the genes responsible for FH (LDLR, APOB, PCSK9 or APOE).

Study variablesAmong other data, the registry includes personal and family health history, anthropometry, physical examination (blood pressure, weight, height, body mass index [BMI]), biochemical parameter data, presence of CV disease, age at which statin treatment started, history of lipid-lowering treatment.

Cardiovascular disease was defined as: coronary (myocardial infarction, coronary revascularisation procedure, sudden death), cerebral (ischaemic stroke with neurological deficit > 24hours without evidence of bleeding on brain imaging), peripheral vascular (intermittent claudication with ankle-brachial index < .9 or lower limb arterial revascularisation) or symptomatic or asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm.

High blood pressure was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90mmHg or taking anti-hypertensive medication.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126mg/dL, HbA1c ≥ 6.5% or treatment with hypoglycaemic drugs. The variable smoking was defined as current smoker when the consumption was at least one cigarette in the last month, ex-smoker when the subject had not smoked anything for at least one month, and non-smoker when not having smoked anything in the last month and the number of cigarettes smoked in a lifetime was less than 50. Current smoking was defined as current smoker or ex-smoker of less than one year, with a smoker being someone who smoked at least 50 cigarettes in his or her lifetime. Statin strength was defined according to the criteria of the American Heart Societies' document on the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia.4

Patient follow-upA total of 1,665 study subjects had clinical follow-up information from the units. The mean follow-up was 4.2 years. Clinical outcome data included: new CV events, DM or hypertension; anthropometric data: systolic and diastolic BP, weight and BMI, analytical data: total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides, uric acid, creatinine, apolipoprotein B, glucose, GGT, ALT, AST, and changes in lipid-lowering therapy. LDL-C was calculated by the Friedewald formula when triglycerides were less than 400mg/dL.

We conducted this study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki for the protection of the rights and welfare of persons participating in biomedical research.

Statistical analysisThe variables were summarised as a mean (standard deviation) for normally distributed variables, median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed variables or percentage for qualitative variables. Unadjusted differences between groups were performed with Student’s t-tests, Kruskal-Wallis or χ2 tests, as appropriate. All data analyses were performed with SPSS versión 21.

ResultsClinical characteristicsPatients were divided into primary and secondary prevention, of 3,439 and 519 subjects with mean ages of 51 and 57 years, respectively. The main characteristics of the two groups are presented in Table 1. Differences were found between the anthropometric and biochemical parameters, including total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-C and lipoprotein (a) (Lpa(a)). Furthermore, as expected, with regards to associated comorbidities, there were more hypertensives, diabetics and smokers in secondary prevention. Regarding statin treatment length, patients in secondary prevention had been under treatment longer (mean 8.3 years vs. 5.3 years in primary prevention patients. A total of 2,270 (66.0%) of subjects in primary prevention and 482 (92.9%) in secondary prevention had a history of lipid-lowering treatment on inclusion in the register.

Baseline clinical and biochemical characteristics in the Registry subjects divided in primary and secondary prevention.

| Mean (SD)/percentage [n] | Primary | Secondary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD)/% | n | Mean (SD)/% | p | |

| Age (years)) | 3,439 | 51 (±12) | 519 | 57 (±10) | < .001 |

| Sex, female % [n] | 3,439 | 50.2 [1.728] | 519 | 29.7 [154] | < .001 |

| Weight (kg) | 3,.424 | 75.3 (±14) | 516 | 79.4 (±13.2) | < .001 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 3,422 | 27.2 (±4) | 516 | 28.5 (±4) | < .001 |

| Waist (cm) | 3,019 | 92.9 (±12.2) | 414 | 99.0 (±12) | < .001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 3,321 | 131.2 (±17) | 496 | 135.0 (±19) | < .001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 3,319 | 80.0 (±10) | 496 | 80.1 (±10) | .038 |

| High blood pressure, % [n] | 3,391 | 27.0 [914] | 510 | 55.3 [282] | < .001 |

| Diabetes mellitus 2, % [n] | 3,406 | 11.1 [378] | 513 | 31.8 [163] | < .001 |

| Smoking history, % [n] | 3,019 | 31.7 [980] | 414 | 46.4 [192] | < .001 |

| Cigarette packs per day x years of smoking | 980 | 24.7 (18.8) | 192 | 37.3 (26.2) | < .001 |

| History of previous lipid lowering treatment, % [n] | 3,439 | 66.0 [2270] | 519 | 92.9 [482] | < .001 |

| Time with statins (years) | 2,586 | 5.3 (±6) | 383 | 8.3 (±6.7) | < .001 |

| Untreated total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 3,439 | 314 (±70.0) | 519 | 323 (±83.7) | < .005 |

| Untreated triglycerides (mg/dL) | 3,438 | 155 (104-260) | 519 | 188 (126-288) | < .001 |

| Untreated HDL-C (mg/dL) | 3,439 | 54.1 (±16.7) | 519 | 46.5 (±14.6) | < .001 |

| Untreated LDL-C (mg/dL) | 2,938 | 222 (±72.9) | 440 | 229 (±73.0) | .016 |

| Untreated non-HDL-C (mg/dL) | 3,439 | 260.1 (±68.5) | 519 | 277.7 (±82.1) | < .001 |

| Lipoproteín (a) (mg/dL) | 2,156 | 26.7 (9.36-77.9) | 286 | 48.5 (12-99.6) | < .001 |

| Untreated glucose (mg/dL) | 3,078 | 99.8 (±24.4) | 453 | 114.21 (±36.5) | < .001 |

Continuous data expressed as mean (SD); categorical data are expressed as percentages (number); quantitative data expressed with ranges (median - interquartile range).

HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Non-HDL cholesterol.

Table 2 contains the lipid-lowering drugs the people were taking when they were included in the register. The most commonly used drugs were statins which were prescribed in 73.8% of primary prevention subjects and 87.3% in secondary. Over 50% of the secondary treatment subjects were treated with ezetimiba. The use of fibrates was present in about 8% of subjects with no differences between groups. Treatment was significantly different in primary and secondary prevention, and almost 90% of the subjects in secondary prevention of those taking a statin were on a high-strength statin (Supplementary Table S1).

Lipid-lowering drugs at inclusion in the Registry in primary and secondary prevention subjects.

| Drug | Primary n=3,439 | Secondary n=519 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statins, % [n] | 73.8 [2539] | 87.3 [453] | < .001 |

| Ezetimiba, % [n] | 20.8 [717] | 53.0 [275] | < .001 |

| Fibrates, % [n] | 8.3 [285] | 8.1 [42] | .280 |

| Other treatments, % [n] | 2.0 [70] | 5.0 [26] | < .05 |

The main treatment combinations at the time of inclusion in the registry are described in Supplementary Table S2; 19.6% in primary prevention took the combination statin plus ezetimibe and 50.9% in secondary prevention. When the combination was used, atorvastatin and rosuvastatin were again the most commonly used statins. There was no difference in the use of the statin plus fenofibrate combination, which was only used in about 7% of subjects in both primary and secondary prevention. In this case, the use of pravastatin was higher, reaching 24.1% in primary prevention.

Statin strength at the time of inclusion in the registry is described in Table 3. Seventy-five per cent of secondary prevention subjects were taking a high-strength statin which would be what was recommended by the guidelines. The mean daily statin dose is described in Supplementary Table S3. Doses were higher in secondary prevention than in primary prevention for all statins, although they reached statistical significance only for rosuvastatin, simvastatin and atorvastatin. The mean dose of statins in secondary prevention is close to the maximum recommended dose, although it is approximately 50% in primary prevention subjects.

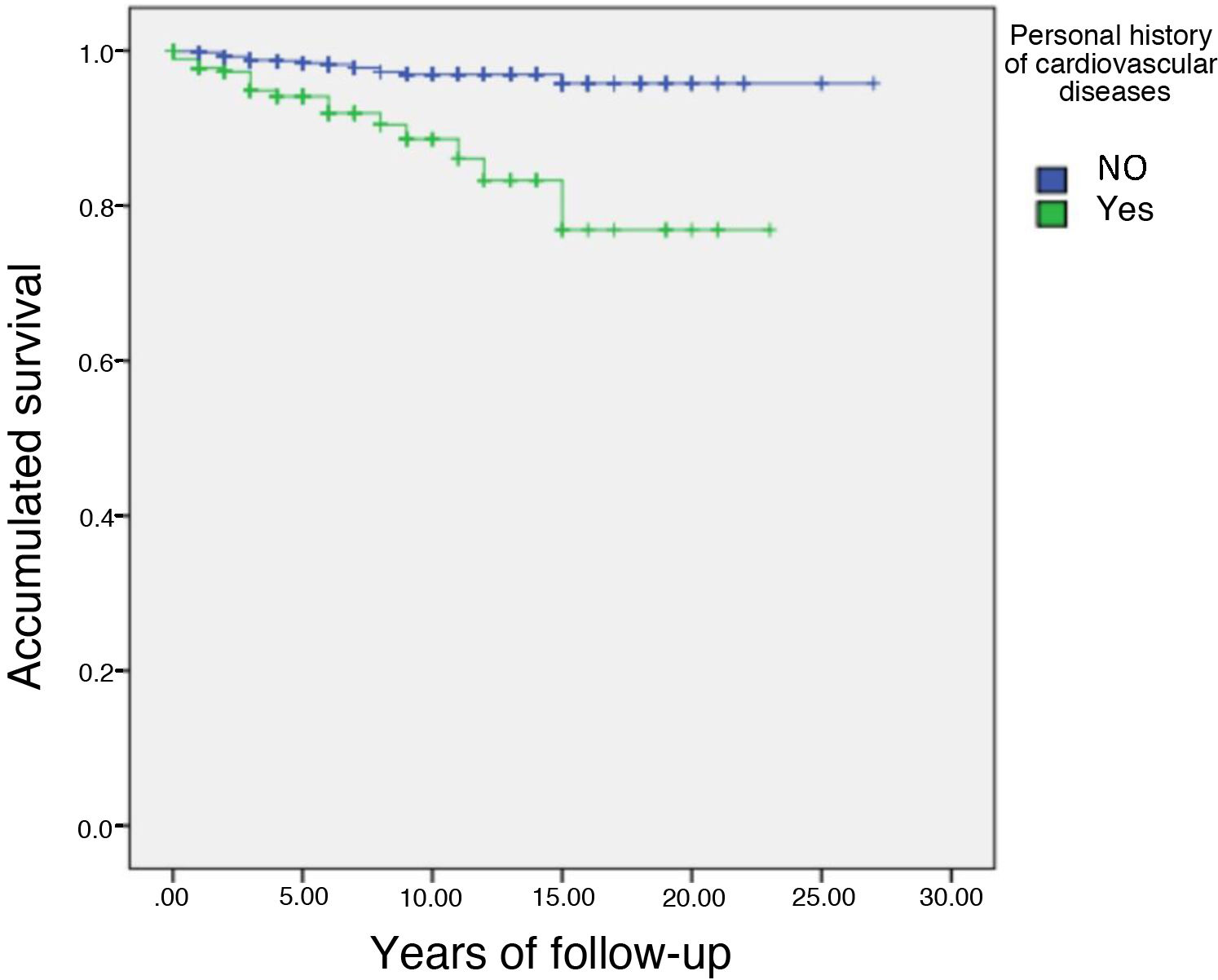

Table 4 describes the anthropometric characteristics, personal history, risk factors and untreated lipid concentrations of those subjects who had or had not experienced a CV event. Data are presented according to whether or not the subjects had a CV event during follow-up. The mean follow-up of the 1,665 subjects with follow-up data was 4.2 years, representing a mean follow-up of 6,993 subjects/year. A total of 42 subjects had a cardiovascular event from inclusion in the registry until data closure of this analysis on 3 March 2021. The incidence of cardiovascular event during follow-up was .6% per year. This reflects the very reasonable cardiovascular risk management of the subjects included in the registry. Subjects who had an event were older, had a three-times longer history of cardiovascular disease (Fig. 1), 28.6% had a history of DM and a higher history of smoking than subjects who did not have an event at follow-up. When analysing lipid data, the Lp(a) concentration was twice as high in subjects who had an event at follow-up compared to those who did not. However, there were no significant differences in HDL-C, LDL-C and non-HDL-C (non-HDL-C) cholesterol. In summary, subjects with events at follow-up were older, more of them were smokers, with a higher prevalence of DM and with a higher Lp(a) concentration.

Baseline clinical and biochemical characteristics WITHOUT TREATMENT of subjects with follow-up depending on whether they have had a cardiovascular event in the course of follow-up.

| No CVE n=1,623 | Yes CVE n=42 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.0 (47.0-61.0) | 58.0 (53.0-65.3) | .001 |

| Sex, female % (n) | 46.6 (737) | 42.9 (18) | .630 |

| Weight (kg) | 76.3 (66.4-84.1) | 74.8 (65.9-85.4) | .848 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 27.2 (25.0-30.0) | 27.2 (25.0-30.3) | .678 |

| Waist (cm) | 93.0 (85.0-102) | 94.0 (87.0-101) | .495 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 131 (120-144) | 133 (19-154) | .529 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 81.0 (74.0-87.0) | 81.0 (74.0-86.0) | .806 |

| High blood pressure, % (n) | 34 (538) | 50 (21) | .094 |

| Cardiovascular disease, % (n) | 16.6 (263) | 45.2 (19) | < .001 |

| Diabetes mellitus 2, % (n) | 14 (222) | 28.6 (12) | .029 |

| Smoker, % (n) | 20.4 (323) | 14.3 (6) | .734 |

| Non smoker, % (n) | 43.8 (693) | 42.9 (18) | |

| Ex smoker, % (n) | 34.7 (548) | 42.9 (18) | |

| Packs of cigarettes per day | 25.0 (14.0-38.0) | 36.0 (27.0-65.0) | .015 |

| Lipid-lowering treatment, % (n) | 87.5 (1384) | 97.6 (41) | .049 |

| Statin duration (years) | 4.00 (1.00-9.00) | 6.00 (2.00-10.0) | .086 |

| Untreated total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 292 (265-330) | 297 (268-332) | .734 |

| Untreated triglycerides (mg/dL) | 159 (105-250) | 160 (109-252) | .563 |

| Untreated HDL-C (mg/dL) | 52.0 (43.0-63.0) | 49.0 (40.0-58.25) | .099 |

| Untreated LDL-C (mg/dL) | 201 (180-236) | 209 (173-238) | .725 |

| Untreated Non-HDL-C (mg/dL) | 236 (211-275) | 250 (213-282) | .381 |

| Lp(a) (mg/dL) | 29.3 (10.5-81.0) | 59.5 (33.1-120) | .001 |

| Untreated glucose (mg/dL) | 96.0 (88.0-107) | 100 (92.0-125) | .058 |

Continuous data expressed as mean (SD); categorical data expressed as percentages (number); quantitative data expressed as ranges (median - interquartile range).

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular event; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein (a).

Supplementary Table S4 describes the lipid parameters when subjects start follow-up in the Lipid Unit. These data reflect the lipid concentrations after initiation of treatment in the different units. As can be seen in the table, it is striking that there were no significant differences between subjects who did or did not develop an event at follow-up with the exception of HDL-C, which was 3mg/dL lower (50.0mg/dL vs. 53.0mg/dL) in subjects with an event. With respect to baseline concentrations, we can observe a mean reduction in LDL-C of around 50% from more than 200mg/dL to around 110mg/dL. However, it is of note that the LDL-C concentration was not different between the two groups.

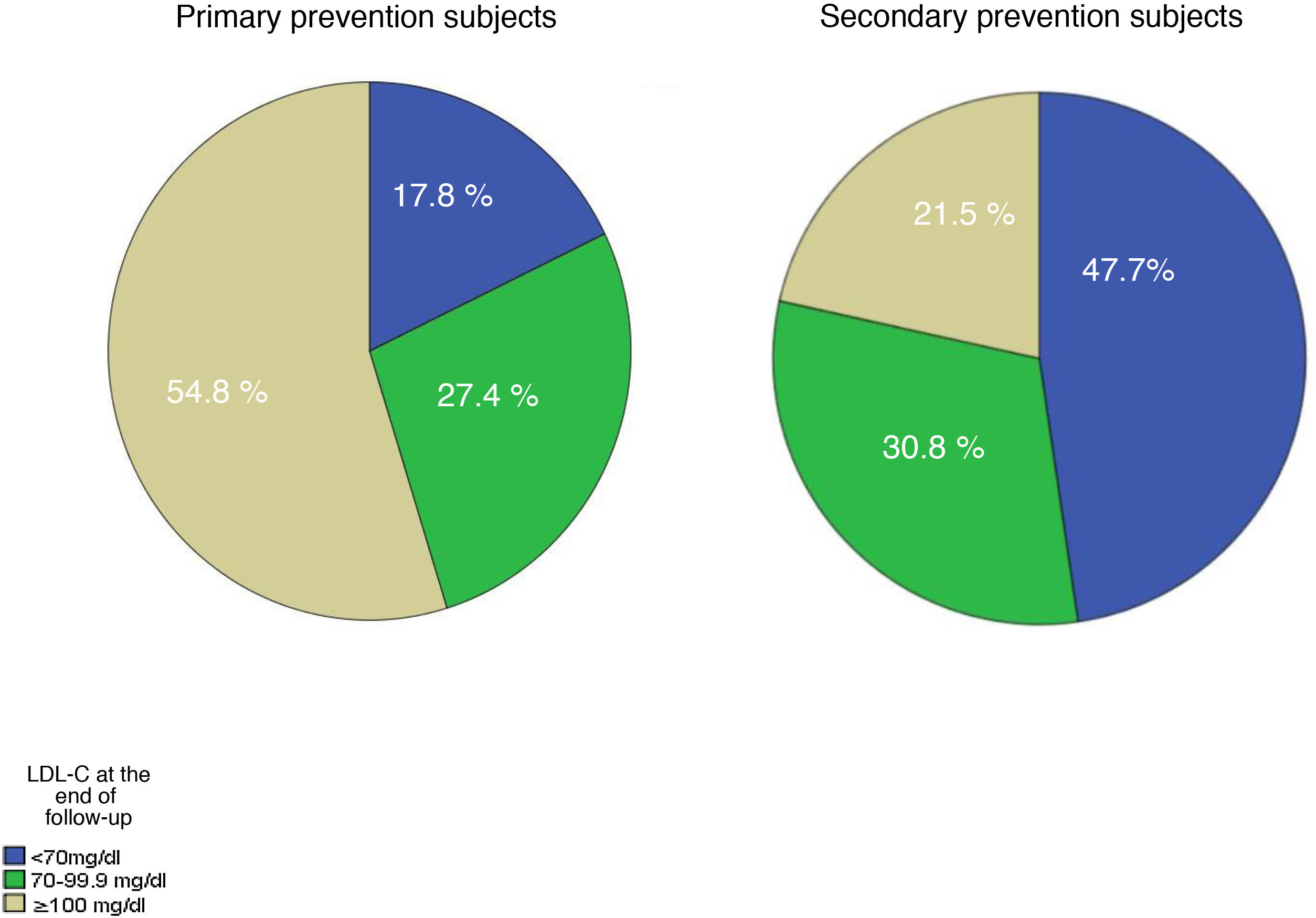

Table 5 shows the lipid data at the end of follow-up. The decrease in practically all lipid profiles of the subjects who had a cardiovascular (CV) event during follow-up can be seen with very significant differences. The percentage of subjects who reached the different LDL-C targets is shown in Fig. 2. In glucose, a slight increase is detected, which could be due to the association of diabetes as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Biochemical characteristics at the end of follow-up depending on whether they have had a cardiovascular event during follow-up.

| No CVE n=1,623 | Yes CVE n=42 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 190 (160-221) | 154 (127-174) | < .001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 116 (88.0-170) | 133 (81.0-156) | .719 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 54.0 (45.0-64.0) | 50.0 (40.0-60.3) | .048 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 105 (77.2-132) | 77.8 (52.0-93.0) | < .001 |

| Non-HDL-C (mg/dL) | 134 (107-163) | 99.0 (79.8-120) | < .001 |

| Apolipoprotein B (mg/dL) | 105 (87.0-123) | 81.5 (59.4-101) | < .001 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 99.0 (91.0-110) | 110 (93.0-129) | .004 |

Quantitative data expressed with ranges (median - interquartile range). CVD: cardiovascular event; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

The lipid lowering treatment the subjects received at baseline is described in supplementary Table 5. Again, the subjects are divided between those who did not develop an event and those who did. The overall differences were not significant with the most striking being the prescription of a high strength statin combined with ezetimibe, which was initiated in 11.7% of subjects who did not develop an event and 26.6% of subjects who did.

Finally, the drug combinations at the end of follow-up are described in Table 6. The use of medium-high strength statins together with ezetimibe was the most frequently used treatment in subjects who had an event. However, medium-strength statins in monotherapy predominated in subjects who had not experienced an event. Another striking finding is the percentage of subjects who received combination therapy with PCSK9 inhibitors (iPCSK9) but without statins, suggesting that these subjects were intolerant to statins and that the indication for iPCSK9 was a result of the same.

Lipid-lowering drug groups at last follow-up visit.

| No CVE n=1,539 | Yes CVE n=39 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No treatment, n (%) | 87 (5.70) | 0 | < .001 |

| Low strength statin, n (%) | 34 (2.20) | 0 | |

| Low strength statin+ezetimiba, n (%) | 4 (.30) | 0 | |

| Medium strength statin, n (%) | 494 (31.2) | 5 (11.9) | |

| Medium strength statin+ezetimiba, n (%) | 198 (12.5) | 7 (16.7) | |

| High strength statin, n (%) | 269 (17.0) | 7 (16.7) | |

| High strength statin+ezetimiba, n (%) | 238 (15.1) | 13 (31.0) | |

| Statins+fibrates, n (%) | 75 (4.70) | 0 | |

| Monotherapy fibrates, n (%) | 32 (2.00) | 0 | |

| Statin+iPCSK9, n (%) | 11 (.6) | 0 | |

| iPCSK9 without statin, n (%) | 32 (2.00) | 3 (7.10) | |

| Statin+ezetimiba+iPCSK9, n (%) | 30 (1.8) | 4 (9.5) | |

| Others, n (%) | 35 (2.20) | 0 |

CVE: Cardiovascular event; Inhibitors PCSK9: iPCSK9.

This analysis of the data from the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis Registry (excluding subjects with familial hypercholesterolaemia) reflects:

- 1

A low incidence of cardiovascular disease during follow-up, around .6% per year, which is possibly a consequence of the multifactorial management of risk factors and the increasing use of more intense lipid-lowering treatments. In our study, the incidence of CV events was very low, as these patients often had associated pathologies such as diabetes, smoking and high Lp(a) concentrations. A total of 42 subjects had a cardiovascular event from their inclusion in the registry until the close of data for this analysis on 3 March 2021; 50% of them, i.e. 21 subjects, were free of cardiovascular disease at the start of follow-up, which represents an annual incidence of .36%, a figure that is even lower than the patients in the JUPITER study with rosuvastatin in primary prevention.6 The same is true for subjects in secondary prevention at baseline whose incidence was 1.8% per year, also lower than the placebo groups in recent iPCSK trials.7–9

- 2

LDL-C concentrations have improved during follow-up, but are still far from achieving optimal therapeutic targets in approximately 50% of the population. Our data are consistent with the EUROASPIRE-V cohort where 8,261 patients, seen in cardiology services, were studied. Their data would coincide with the secondary prevention subjects in our study who, despite being on high doses of statins, had LDL-C concentrations above 90mg/dL at the start of follow-up.1 These values are far from achieving the targets recommended by the ESC/EAS guidelines, recently updated to a recommended LDL-C value of <55mg/dL for secondary prevention subjects.10

- 3

Increasing use of high-strength statins and ezetimibe is observed in up to two thirds of patients in secondary prevention. However, still one third of these patients do not take a high-strength statin. There are very limited studies that have looked at differences in clinical ASCVD events between statins.11–13 The Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Trial (PROVE IT) analysing the differences between these medium- and high-strength statins (atorvastatin 80mg/day, pravastatin 40mg/day) found that atorvastatin was the more protective drug. Greater benefit was concluded for the use of high doses of these types of lipid-lowering drugs.14 The Treating to New Targets (TNT) trial used different doses, but reached identical conclusions.15 In the same vein, the SEA Registry has shown that high doses of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin are of similar efficacy in CV prevention in high-risk subjects.11

- 4

Increasing use of iPCSK9, which, if we consider that subjects with HF are not included, reaches 16.7% in subjects with recurrences, still low for the total number of subjects who were in secondary prevention at the start of follow-up.

Our study has some limitations. It was an observational study where follow-up of patients was variable in time and where only a fraction of the patients included had follow-up data. This was similar for all patients, whether they were primary or secondary prevention and was therefore subject to selection biases.

FundingThis study was funded by a collaboration agreement between Daiichi-Sankyo, the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis. The SEA registry is partially funded by a collaboration agreement between the SEA, Sanofi. The sponsors were not involved in the creation or content of this study which solely expresses the authors’ opinion.

Conflict of interestsPedro Valdivielso states he receives personal fees from Amgen, Sanofi and MSD, grants and personal fees from Ferrer, and personal fees from Esteve. Fernando Civeira states he receives personal fees from Amgen, Sanofi, MSD and Ferrer, separate from this presented paper. The remaining authors have no conflict of interests.