New horizons in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia

More infoDespite the various therapeutic tools available, many patients do not achieve therapeutic goals, and cardiovascular diseases remain a significant cause of death in our setting. Furthermore, even in patients who manage to reduce their LDL-C levels to the recommended targets, cardiovascular events continue to occur.

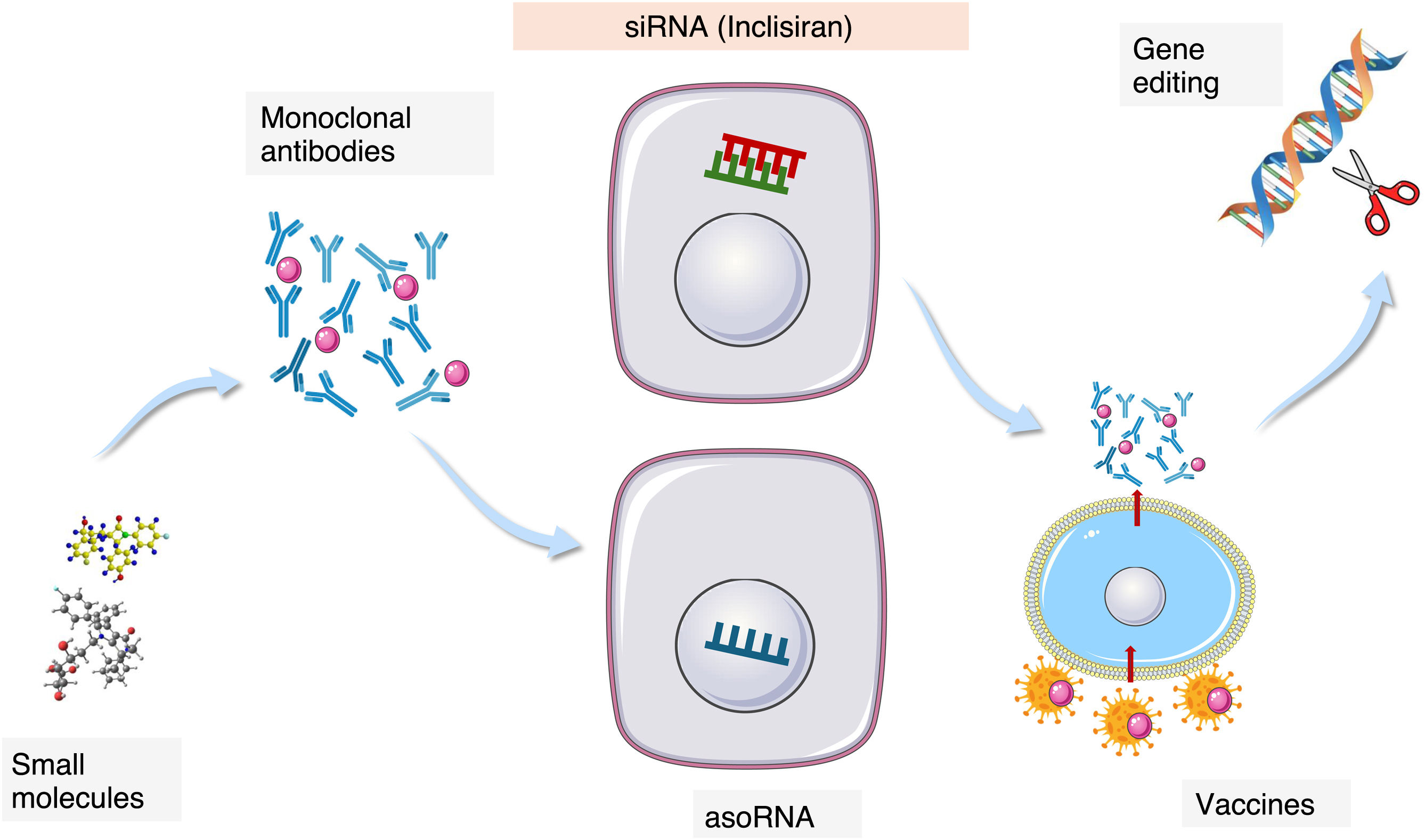

The therapeutic challenge and the persistent risk have led to active research into new drugs targeting novel therapeutic pathways in the field of lipoprotein metabolism disorders. The therapeutic approach involves new pharmacological mechanisms, ranging from small molecules and monoclonal antibodies to RNA interference, with Inclisiran being the first drug approved for clinical use in the cardiovascular domain.

In this review, we aim to provide a comprehensive overview of the new therapeutic targets and pharmacological mechanisms under development, as well as their potential clinical impact.

A pesar de las diversas herramientas terapéuticas de que disponemos, muchos pacientes no alcanzan los objetivos terapéuticos y las enfermedades cardiovasculares siguen siendo una causa muy importante de muerte en nuestro medio. Además, incluso en pacientes que consiguen reducir sus cifras de C-LDL hasta los objetivos recomendados, se siguen produciendo eventos cardiovasculares.

La dificultad terapéutica y el riesgo persistente han propiciado una activa investigación de nuevos fármacos dirigidos a nuevas dianas terapéuticas en el ámbito de los trastornos del metabolismo lipoproteico. El abordaje terapéutico se realiza a través de nuevos mecanismos farmacológicos que van desde las pequeñas moléculas, pasando por los anticuerpos monoclonales y llegando a la interferencia del ARN, de la que Inclisiran es el primer fármaco aprobado para uso clínico en el ámbito cardiovascular.

En esta revisión pretendemos dar una visión amplia de las nuevas dianas terapéuticas y de los nuevos mecanismos farmacológicos en desarrollo y de su posible impacto clínico.

Lipid metabolism is involved in multiple morbidity from cancer to neurodegenerative disorders, including disorders as prevalent as fatty liver caused by metabolic dysfunction. For each of these processes there are a significant number of therapeutic objectives related to lipid metabolism, and there is currently a great deal of recently reviewed1 research activity to develop drugs that modulate lipid metabolism at different metabolic levels.

Doubtless the most important disease, due to its prevalence and clinical significance associated with lipid disorders, is arteriosclerosis and its consequence, atheromatous vascular diseases (AVD). These are the leading cause of mortality and loss of years without disability in our environment.

Arteriosclerosis is a pathological alteration that is located in the intimal layer of the arteries and is the result of an inflammatory and proliferative process initiated by the deposit of cholesterol in the subendothelial area. When there is an excess of cholesterol carried by LDL (LDL-C) and other lipoprotein particles containing apo B, such as triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRL), it accumulates in the arterial wall, crystallises and triggers the atheromatous process. Cholesterol, therefore, should not be considered a risk factor for the disease, but rather its main aetiological factor. The causal role of LDL-C in atheromatosis has recently been reviewed.2

A large body of evidence exists regarding the benefit obtained by reducing plasma LDL-C concentrations on cardiovascular risk. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) using different lipid-lowering drugs such as statins, ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors or bempedoic acid3–7 have confirmed the reduction in cardiovascular events due to the decrease in LDL-C concentrations. This direct relationship has a series of clinical characteristics such as the fact that the determining factor in the reduction of events is caused by the decrease in LDL-C concentrations regardless of the drug used.8 Furthermore, the lower the LDL-C concentration obtained, the greater the clinical benefit, without a lower limit having been detected from which no additional benefit is obtained.9 The relationship between the time and intensity of exposure to high LDL-C concentrations and the risk of suffering cardiovascular events10 is highly apparent with the result that the earliest, most intense and most persistent actions are those associated with a greater clinical benefit.11 The advent of drugs that provide convenience and simplicity in their administration, lipid-lowering efficacy and persistence in their effects must surely provide great clinical aid.

Despite the LDL-C reduction capacity available, the number of patients who continue to present events is significant. These patients present a persistent risk due to both extralipid and lipid factors. Among the lipid factors beyond LDL-C concentrations, the atherogenic power of TRL, its remnants12 and molecular components such as apoprotein CIII, and also lipoprotein (a) have been identified. Action on pathogenic factors (inflammation, oxidation, platelet aggregation)13 has also been stimulated.

The magnitude of the clinical and social problem, the scientific evidence and the unresolved problems have activated research in this field, identifying new therapeutic targets and new pharmacological mechanisms, which are the objective of this article.

New therapeutic targetsReducing the LDL-C, the primum movens of lipid-lowering therapyAs stated, cholesterol transported by LDL is the main aetiological factor of arteriosclerosis.2,11 Among the many pieces of evidence that support this fact is the reduction of CV risk linked to the decrease in circulating concentrations of LDL-C. For this reason, the reduction of LDL-C has been the subject of intense pharmacological research with the identification of various therapeutic targets. Most therapies act by increasing the clearance of LDL particles through the activation of their receptor.

The limiting enzyme of intracellular cholesterol synthesis, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGCoAr) is the target of statins. Its inhibition reduces intracellular cholesterol, causing an increase in the synthesis of LDL receptors and thus an increase in plasma clearance of LDL. ATP citrate lyase acts in the same metabolic pathway, a couple of enzymatic steps before HMGCoAr and, therefore, exerting the same metabolic actions. Bempedoic acid inhibits this enzymatic step specifically at the hepatic level.14

Digestive absorption of cholesterol is meticulously controlled and is carried out through a specific receptor, Nieman Pick C1L1, located in the luminal pole of enterocytes. Its blockage limits cholesterol absorption. In addition, it is expressed in the biliary pole of hepatocytes to facilitate the reuptake of part of the cholesterol released into the bile, so its inhibition also limits the arrival of cholesterol to the interior of the hepatocyte. Hepatocito.15 Both actions cause an increase in the expression of LDLR.

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) is synthesised in the liver at 80%, and is secreted into the bloodstream where it binds to LDLR. In the presence of PCSK9, when LDLR is internalised together with an LDL particle, instead of being recycled to the membrane, it is degraded, so that the expression of LDLR in the hepatocyte membrane is reduced.16 Different pharmacological strategies aim to reduce or block this protein, which leads to an increase in the expression of LDL. Anti-PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies (alirocumab and evolocumab) block circulating PCSK9, while inclisiran blocks its synthesis.

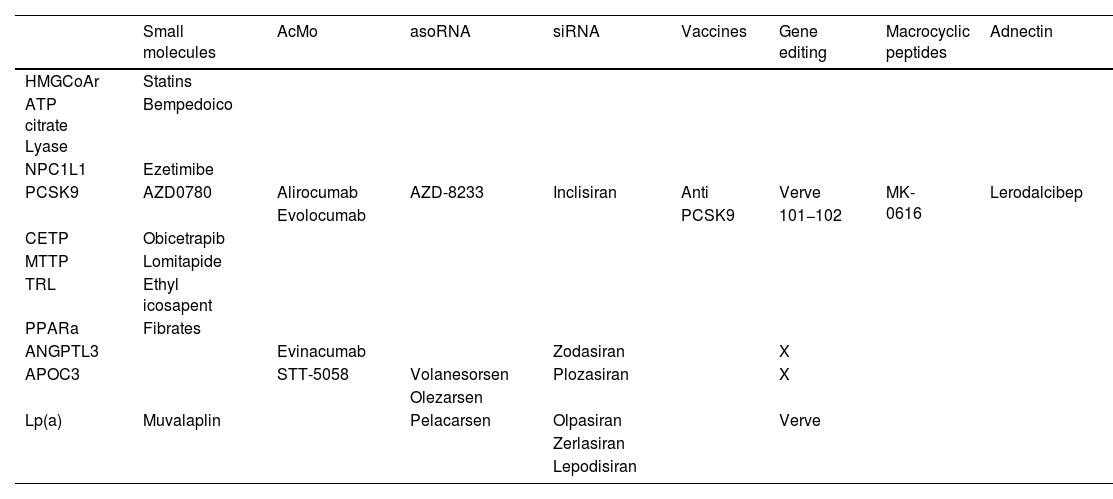

Pharmacologoical actions on triglyceride-rich particlesAs indicated at the beginning of this article, despite achieving very low concentrations of LDL-C, a certain, non-negligible degree of cardiovascular risk associated with lipid alterations persists. This has motivated the search for additional therapeutic targets, including interventions aimed at reducing LDL (chylomicrons, VLDL, their remnants, IDL, etc.) and some of their components (Table 1).

Drugs aimed at treating dyslipidaemias classified according to therapeutic target and pharmacological mechanism.

| Small molecules | AcMo | asoRNA | siRNA | Vaccines | Gene editing | Macrocyclic peptides | Adnectin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMGCoAr | Statins | |||||||

| ATP citrate Lyase | Bempedoico | |||||||

| NPC1L1 | Ezetimibe | |||||||

| PCSK9 | AZD0780 | Alirocumab | AZD-8233 | Inclisiran | Anti | Verve | MK-0616 | Lerodalcibep |

| Evolocumab | PCSK9 | 101−102 | ||||||

| CETP | Obicetrapib | |||||||

| MTTP | Lomitapide | |||||||

| TRL | Ethyl icosapent | |||||||

| PPARa | Fibrates | |||||||

| ANGPTL3 | Evinacumab | Zodasiran | X | |||||

| APOC3 | STT-5058 | Volanesorsen | Plozasiran | X | ||||

| Olezarsen | ||||||||

| Lp(a) | Muvalaplin | Pelacarsen | Olpasiran | Verve | ||||

| Zerlasiran | ||||||||

| Lepodisiran |

ANGPTL3: angiopoietin like 3; ApoC3: apolipoprotein 3; asoRNA: antisense oligonucleotide RNA; CETP: cholesterol ester transfer protein; HMGCoAr: hydroxy-methyl-glutaryl coenzyme A reductase; Lp(a): lipoprotein (a); TRL: triglyceride-rich lipoproteins; MOAs: monoclonal antibodies; MTTP: microsomal triglyceride transfer protein; NPC1L1: Niemann-Pick C1L1; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; PPARa: peroxisomal proliferator receptor activator alpha; siRNA: small interfering RNA; X: very early-stage drug projects.

Blocking the formation of VLDL should result in a decrease in all lipoproteins except HDL.

Among the therapeutic targets aimed at reducing TRL concentrations, apolipoprotein B:100 stands out, which is the fundamental protein in the constitution of all lipoprotein particles except HDL. Patients with genetic defects in the synthesis of apo B, such as those affected by heterozygous familial hypobetalipoproteinaemia, usually have a life without relevant side effects except for a greater tendency to fatty liver in some cases. Mipomersen, however, was not approved by the EMA due to its side effects in the form of significant lesions at the injection sites.17 The microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTTP), responsible for binding triglycerides to apo B, is another therapeutic target addressed by the drug lomitapide. The maturation and viability of apo B requires its binding to triglycerides. Its blockage produces significant reductions in all lipoprotein particles.18

An interesting approach has been the search for inhibitors of triglyceride synthesis, which would lead to lower fat content in the liver and lower production of VLDL (very low-density lipoprotein) in general. In this sense, only n-3 fatty acids reduce triglycerides by acting in part on the anabolic phase of the same or directing them towards beta oxidation instead of the formation of triglycerides.

Pharmacological targets aimed at increasing plasma clearance of TRLThe central target of this approach is lipoprotein lipase (LPL), an enzyme found on the endothelial surface of tissues such as adipose and muscle, and is responsible for hydrolysing the triglycerides of TRL so that their fatty acids become part of the energy storage in adipose tissue or provide energy in muscle tissue. Due to their action at the plasma level, TRLs are converted into residual, remnant particles, subsequently into intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL) and finally into LDL. The regulation of their expression is mediated, among others, by the transcription factors called PPAR alpha. Fibrates activate them, which is why they have been used to improve their activity and, therefore, increase the clearance of TRLs. The action of LPL is key in the functioning of the lipoprotein metabolic cascade and is precisely regulated by a significant number of proteins that modulate its functionality, activating or inhibiting it. Among them, angiopoietin like 3 (ANGPTL-3) is a substance that inhibits LPL (in addition to hepatic and endothelial lipase), so that its blockage activates the function of LPL.19 Patients with deficiencies of this protein have a lower concentration of all lipoprotein particles and lower cardiovascular risk, which is why its blockage became a therapeutic target. Evinacumab acts in this way, having been observed that in addition to increasing clearance due to greater LDL activity, it facilitates the clearance of the remaining TRL at the hepatic level, producing an overall reduction of atherogenic particles. Another protein of great therapeutic interest is apolipoprotein CIII, which circulates associated with TRL and has the function of inhibiting LPL, although it also acts by slowing down the clearance of TRL. In addition, it itself has a pro-inflammatory action.20 Its inhibition (volanesorsen, olezarsen…) is associated with a clear reduction of triglycerides and TRL in general.

TRLs condition the composition of the rest of the lipoproteins by exchanging lipid molecules with cholesterol-rich lipoproteins (LDL, HDL). Various circulating proteins are involved in this lipid exchange, including the cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) that allows the exchange of triglycerides for cholesterol between said lipoproteins.21 The result of this effect is a reduction of cholesterol in HDL, so its inhibition was considered of interest to increase HDL cholesterol concentrations. They are also associated with a reduction of c-LDL, so despite certain studies in which no benefit was observed in its action, its impact on c-LDL has been taken up again as a new line of pharmacological development (obicetrapib).

And Lp(a) moment arrivesLipoprotein (a) (Lp(a)) is an LDL particle to which a protein called apolipoprotein (a) binds, probably in the hepatic cellular interstitium. It is not the aim of this article to review the physiological or pathogenic aspects of the Lp(a) particle, for which we recommend some recent documents.22,23 Apo(a) is a protein whose structure has certain similarities with plasminogen, and its gene probably derives from duplications and deletions of the plasminogen gene. Its plasma concentrations depend on the size of the apo(a), determined 85% genetically. The particle is highly atherogenic, proinflammatory and thrombogenic, without any known relevant physiological role for it. People who hereditarily have low concentrations of Lp(a) have a lower risk of EVA while high concentrations are clinically associated with a greater number of cardiovascular events, so its inhibition is a clear therapeutic objective.

New pharmacological mechanisms of actionSmall moleculesMost of the drugs we use in medical therapy are small molecules of different biochemical origin that are usually administered orally. The characteristics of the molecules determine their pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. In the area of lipoprotein metabolism, most of the classic treatments such as statins, ezetimibe or fibrates fall into this category. Among the new therapeutic additions there are also small molecules, among which bempedoic acid and lomitapide stand out as LDL-C reducers. CETP inhibitors, obicetrapib, and even Lp(a) inhibitors, muvalaplin and a PCSK9 inhibitor (AZD0780).

Bempedoic acid is a small molecule, which as a prodrug is activated exclusively in the liver where it acts by inhibiting ATP citrate lyase, an enzyme in the cholesterol synthesis chain at the hepatic level. It acts in the same chain of action as statins. It reduces LDL-C by about 23% or slightly less in the presence of statins. It is a well-tolerated drug and its side effects are scarce and clinically controllable.24

Lomitapide is a small molecule that inhibits MTTP and, therefore, decreases the production of VLDL and, consequently, all the particles derived from them such as LDL. It also inhibits the formation of chylomicrons. Its fundamental effect is the reduction of atherogenic particles very effectively (more than 50% decrease in c-LDL) independently of the LDL receptor pathway, which is why its use is focused on patients with severe defects in this metabolic pathway and specifically on patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Given the severity of the clinical picture, the side effects that may occur are assumed, such as the accumulation of fat in the liver, which can be managed by modulating the doses or the absorption deficits of fat-soluble vitamins that require the administration of supplements.25

Obicetrapib is a CETP inhibitor that, despite the failures of its predecessors, appears to have a good safety profile and, based on its reduction in LDL-C, is expected to join the lipid-lowering therapeutic arsenal.26

Muvalaplin is an oral drug in the initial stages of pharmacological development that blocks the binding site of apo(a) to apo B, preventing the formation of Lp(a).27

Ethyl icosapent (highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid) cannot be considered a small molecule, but is an orally administered drug that reduces TRL, having demonstrated an important effect in cardiovascular prevention,28 although this appears to be mediated by its anti-inflammatory, antiaggregant and antioxidant effects.

Monoclonal antibodiesThe use of monoclonal antibodies has become widespread in various medical fields for the management of oncological, immune or inflammatory processes and also in the cardiovascular field. Alirocumab and evolocumab are 2 types of antibodies directed against PCSK9. By blocking its binding to the LDLR, they prevent it from acting by accelerating the degradation of the LDLR as we have previously mentioned. They are administered subcutaneously once or twice a month depending on the preparation and their tolerance is good. Alirocumab 75 mg/every 15 days reduces LDL-C by about 50%, alirocumab 300 mg per month produces reductions greater than 50%, while alirocumab 150 mg and evolocumab 140 mg/every 15 days reduce LDL-C by more than 60%.5,6

Evinacumab is an anti-ANGPTL3 monoclonal antibody that is administered by intravenous infusion once a month. It reduces the concentrations of all lipoproteins. Given its high efficacy in reducing LDL through LDLR-independent pathways, its use has been approved for patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, and together with lomitapide, it constitutes the current alternative to LDL apheresis in these patients.29

STT-5058 are highly specific monoclonal antibodies aimed at blocking apo CIII. Its intravenous and subcutaneous forms of administration are being explored for the treatment of severe hypertriglyceridaemia, and are currently in the initial stages of pharmacological development.30

Blocking the translation of messenger RNA into protein. A therapeutic revolutionAll the mechanisms discussed so far focus on modulating, modifying or inhibiting the action of a protein already synthesized. Blocking protein synthesis by interfering in the translation of its messenger RNA is a novel methodology, based on natural mechanisms of genetic regulation, and which has opened therapeutic access to aspects previously inaccessible to it, such as the elimination of abnormal proteins whose accumulation can cause severe diseases. In the field of cardiovascular diseases and specifically in the area of lipid metabolism, there are several molecules in development aimed at various therapeutic targets of those mentioned in the previous sections.

It is possible to distinguish 2 basic forms of mRNA interference, antisense oligonucleotides and small interfering RNAs (asoRNA and siRNA).31,32

The generalisation of these therapies has arisen from the development of their conjugation with the glycopeptide N-acetylgalactosamine. This molecule directs the different RNA constructions specifically towards the hepatocytes given its affinity for the receptors of asialated glycoproteins present on the liver surface. The high specificity of action that N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNac) confers to these therapies has increased their efficacy and safety.33

Antisense RNA oligonucleotidesThese are single-stranded oligonucleotides made up of 18–21 nucleotides, which are generally administered subcutaneously, penetrate the cell nucleus and locate the complementary mRNA chain with precision specificity, blocking its translation into protein by generating RNAse recognition zones that destroy the RNA. In the most recent preparations, the asoRNA is conjugated to GalNac.

This methodology has been developed to block various therapeutic targets related to lipoprotein metabolism.

AZD8233 (ION-863633) is an ASO targeting PCSK9, conjugated to GalNac. It is administered subcutaneously. Phase 2 studies suggest high cholesterol-lowering efficacy with few side effects.34

Volanesorsen is an ASO targeting apo CIII. It reduces triglycerides by around 70% even in patients with LPL deficiency. It is administered subcutaneously every one or two weeks. It is marketed in Spain for the treatment of familial chylomicronemic syndrome. The development of thrombocytopenia has been observed, in some severe cases.35

Olezarsen is also an anti-apo CIII ASO, but conjugated to GalNac, so its action is specific to the liver. Its pharmacological development is in phase 3 and shows an efficacy profile similar to the previous one with less frequent administration and apparently without the development of thrombocytopenia.36

Clinical development of Vupanorsen, an anti-ANGPTL3 ASO, was halted due to lack of clinical efficacy and some side effects.37

Pelacarsen is an anti-apo(a) ASO conjugated to GalNac, which prevents the formation of Lp(a). It is administered subcutaneously monthly, resulting in decreases in Lp(a) of around 80%. Its safety profile is good. Several phase 3 studies are currently underway, including the evaluation of its efficacy in preventing cardiovascular events.7

Small interfering RNAsSmall interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are double-stranded structures composed of about twenty nucleotides. Their function is similar to the aforementioned ASOs, that is, blocking the translation of RNA into protein. They act differently from ASOs since once internalised in the liver cell through the mediation of GalNac, one of the chains, acting as a guide in the intracellular path, directs the oligonucleotide construction towards the cell cytoplasm, unlike ASOs that act in the nucleus. Once there, the guide chain separates and is degraded, while the antisense strand is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) where the translation of RNA into protein takes place. This antisense strand specifically locates the target RNA and conjugates with it, blocking the translation into protein, creating a target for the action of RNases that will degrade the target RNA. In general, the integration of siRNA into the RISC allows its action over a prolonged period of time, which usually facilitates a longer interval between doses to be administered.

This therapeutic mechanism has been used to develop therapies targeting PCSK9 (inclisiran), anti-Lp(a), ANGPTL-3 and apo CIII in the lipid-cardiovascular field. In all cases, the siRNA constructs are conjugated with GalNac to ensure the specificity of their intrahepatocyte action.

Olpasiran is a siRNA, directed against apo (a) that, when administered subcutaneously every 3 months, reduces Lp(a) concentrations by 90%, and even to undetectable lipoprotein values. It is well tolerated and has an adequate safety profile. It is in phase 3 of its pharmacological development.

Zerlasiran is a similar drug that is in phase 1 of its development.

Lepodisiran has also shown similar efficacy to the above, with an administration schedule that can be widely spaced. Its safety profile and cardiovascular effect are currently being studied.38–40

The reduction of ANGPTL3 and apo CIII has also been addressed through the development of siRNA (ARO-ANG3 and ARO-APOCIII). Both molecules appear effective but their pharmacological development is still in the early stages.41

Inclisiran, the first siRNA approved for clinical use in the cardiovascular fieldInclisiran is the first GalNa-conjugated siRNA approved for clinical use in the management of hyperlipidaemia and cardiovascular risk. It is a novel and first-in-class therapy that targets the blockage of PCSK9 mRNA by inhibiting its synthesis, which represents a new pharmacological strategy compared to the use of AcMo, which inhibit the protein once it is formed. There are other siRNAs approved for clinical use in other disease areas such as transthyretin amyloidosis, certain forms of porphyria, and hyperoxaluria. RNA interference is a naturally occurring physiological mechanism that cells use to regulate gene expression, and inclisiran takes advantage of this natural mechanism.

Inclisiran is composed of a double-stranded RNA composed of 21 and 23 nucleotides respectively, which operates in the cytoplasm. One strand of the siRNA acts as a guide, allowing the antisense strand to interact specifically in the RISC complex with the PCSK9 mRNA, leading to its degradation and protein synthesis not occurring. The effect is prolonged because the siRNA remains associated with the RISC complex, blocking the PCSK9 mRNA molecules for a long time. This allows the administration of inclisiran every 6 months, ensuring adherence and the persistence of low LDL-C values.42–44

An important feature of inclisiran is that it is the first marketed drug whose siRNA is conjugated to GalNAc, which is recognised by the asialoglycoprotein receptor present exclusively on the surface of hepatocytes, ensuring that the action of inclisiran is highly specific at the hepatic level.

While inclisiran reduces total circulating PCSK9 levels, MoAb therapies decrease free circulating PCSK9 but increase the total circulating PCSK9 mass by 3- to 10-fold by blocking its binding to the LDLR, which is its main clearance mechanism. The impact of this is unknown, although it does not appear to be of clinical significance.45

Furthermore, MoAbs target all circulating PCSK9, while inclisiran specifically blocks PCSK9 production in the liver, which accounts for the majority (70%–80%) of total circulating PCSK9. However, the extrahepatic part of PCSK9 production that takes place in the intestine, pancreas, kidneys, brain, adipose tissue, and vascular cells is not inhibited by inclisiran, thereby preserving the possible extrahepatic functions of PCSK9.

Among the most interesting pharmacokinetic parameters regarding inclisiran, it is worth noting that plasma concentrations of the drug reach their maximum point approximately between 4 and 6 h after administration, disappearing completely from the bloodstream between 9 and 48 h later, depending on the dose administered. It is of great interest that, despite this short half-life, its therapeutic effects last for several months due to the mechanism mentioned above. That is, the action is persistent in the absence of the drug, which may have its clear advantages in terms of the safety of the product, given that patients are exposed to the presence of the drug in plasma only about 4 days a year.46

The efficacy and safety profiles of inclisiran studied in depth in the ORION programme ORION47,48 are not the subject of this article.

VaccinesInterest in the effect of reducing the action of PCSK9 on LDL-c concentrations and cardiovascular events has led to the search for new therapeutic options, including the development of vaccines to block the protein, which would allow for treatments that would probably be annual. Various approaches have been developed with PCSK9 peptides associated with virus-like particles and other constructs. Some of them have shown good immune stimulation, but with little effect on LDL-C reduction.41

Similar strategies are being developed for the neutralization of ANGPTL3, with still very preliminary results, although promising for their efficacy in reducing LDL-C and triglycerides.41

Gene editingCRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionised the control of gene editing, not only at the experimental level, but also in the clinical field. Blocking DNA to RNA transcription through targeted changes in the genomic sequence has been developed to silence the PCSK9 gene. There are data in primates showing that the effects of reducing PCSK9 and LDL-C persist for a long time. Verve-101 and Verve-102 base their technology on the administration of microparticles that carry the necessary tools to silence the PCSK9 gene specifically in the liver and phase 2 studies are beginning.47

Similarly, there are programs in development for silencing ANGPTL3 and apo(a).

Other pharmacological mechanisms aimed at blocking PCSK9Macrocyclic peptidesThese are complex molecular structures that bind to the catalytic domain of the PCSK9 molecule, inhibiting its interaction with the LDLR. They are administered orally and induce reductions in LDL-C of 60%. The safety and efficacy profile of MK-0616 is being evaluated in phase 348 clinical trials.

AdnectinsThese are proteins derived from the tenth type III domain of fibronectin. Their function is to adhere to various proteins in a similar way to antibodies, that is, with high affinity and specificity. These characteristics have been used to direct these proteins to the active centers of PCSK9 once they have been suitably modified. LIB003 300 mg administered subcutaneously has demonstrated acceptable safety and tolerability, producing reductions of more than 60% in LDL-C concentrations. It is in phase 2 of its pharmacological development49 (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

CompendiumThe therapeutic field of lipid metabolism and especially lipoprotein metabolism is expanding. The identification of new therapeutic targets based on clinical and basic research, and supported by genetic data50 has provided the opportunity of acting on persistent cardiovascular risk beyond the reduction of LDL. The development of new pharmacological tools ranging from small molecules to RNA interference is a step forward that, with the availability of the first anti-PCSK9 siRNA, inclisiran, has ceased to be a future option to become the present of cardiovascular pharmacology (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

CRediT authorship contribution statementLM wrote the first manuscript. LM and DI contributed to the review, writing and final approval of the manuscript.

FundingThis study was funded by an unrestricted grant from the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis.

Additional informationThis article is part of the supplement entitled “New horizons in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia”, which was funded by the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis, with sponsorship from Novartis.

Please cite this article as: L. Masana and D. Ibarretxe, Nuevos fármacos para tratar las dislipemias. De las pequeñas moléculas a los ARN pequeños de interferencia, Clinica e Investigacion en Arteriosclerosis, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arteri.2024.07.004