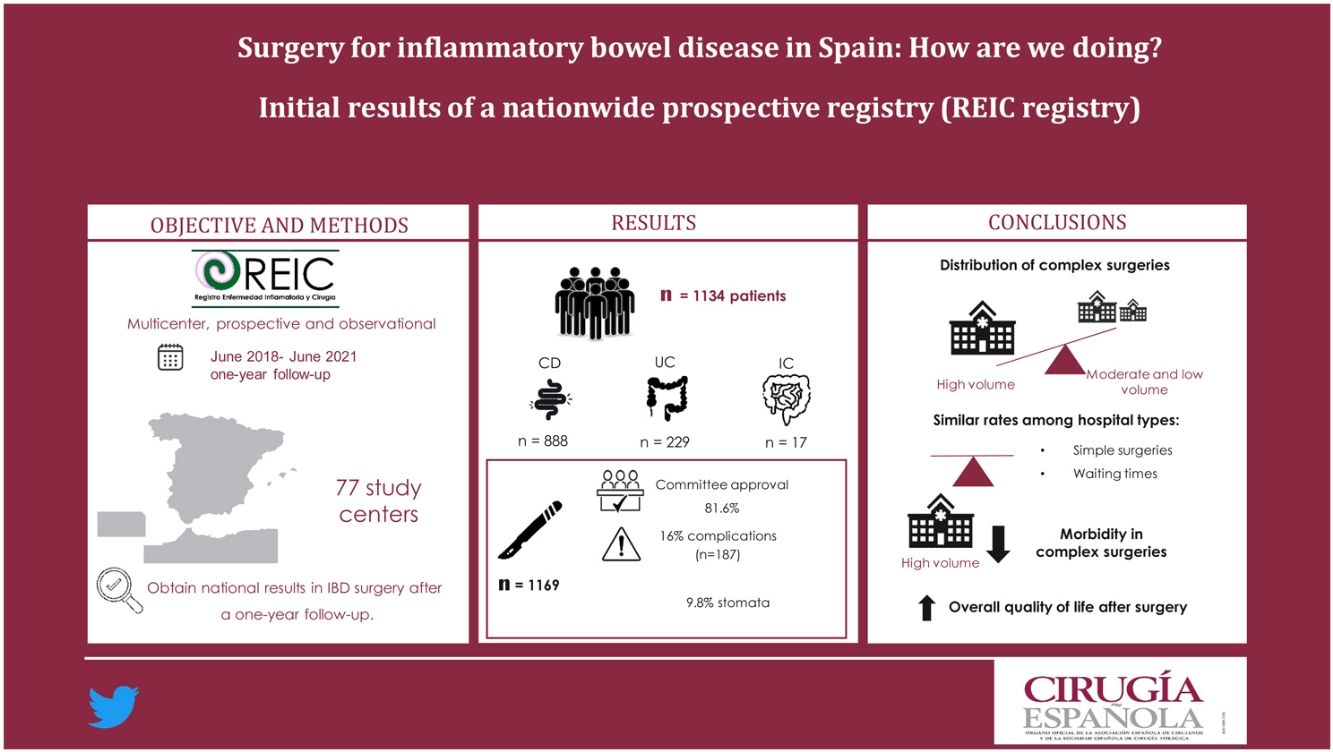

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), requires a multidisciplinary approach, and surgery is commonly needed. The aim of this study was to evaluate the types of surgery performed in these patients in a nationwide study by hospital type, global postoperative complications, and quality of life after surgery.

MethodsA prospective, multicenter, national observational study was designed to collect the results of surgical treatment of IBD in Spain. Demographic characteristics, medical-surgical treatments, postoperative complications and quality of life were recorded with a one-year follow-up. Data were validated and entered by a surgeon from each institution.

ResultsA total of 1134 patients (77 centers) were included: 888 CD, 229 UC, and 17 indeterminate colitis. 1169 surgeries were recorded: 882 abdominal and 287 perianal. Before surgery, 81.6% of the patients were evaluated by a multidisciplinary committee, and the mean preoperative waiting time for elective surgery was 2.09 ± 2 meses (P > .05). Overall morbidity after one year of follow-up was 16%, and the major complication rate was 36.4%. Significant differences were observed among centers in complex CD surgeries. Overall quality of life improved after surgery.

ConclusionsThere is heterogeneity in the surgical treatment of IBD among Spanish centers. Differences were observed in patients with highly complex surgeries. Overall quality of life improved with surgical treatment.

La cirugía constituye un pilar fundamental en el tratamiento de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII), que engloba la Enfermedad de Crohn (EC) y la Colitis Ulcerosa (CU). El objetivo de este trabajo fue estudiar los tipos de cirugía realizados en estos pacientes, según tipo de hospital, las complicaciones postoperatorias globales y calidad de vida después de la cirugía.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un estudio, prospectivo, multicéntrico y observacional a nivel nacional para recoger los resultados del tratamiento quirúrgico de la EII. Se registraron características del hospital, y demográficas, tratamientos médico-quirúrgicos, complicaciones postoperatorias y calidad de vida de los pacientes intervenidos con un seguimiento anual. Los datos fueron validados e introducidos por un cirujano de cada institución.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 1134 pacientes (77 centros): 888 EC, 229 CU y 17 colitis indeterminada. Se registraron 1169 cirugías: 882 abdominales y 287 perianales. El 81,6% de los pacientes fueron evaluados por un comité multidisciplinar antes de la intervención y la media del tiempo de espera prequirúrgico, en cirugía electiva, fue de 2,09 +/- 2 meses (p > 0.05), entre tipos de centro. La morbilidad anual global fue del 16%, con un 36,4% de complicaciones mayores, objetivandose diferencias entre centros en cirugías complejas de EC. Se observó una mejora de la calidad de vida de forma global tras la cirugía.

ConclusionesExiste heterogeneidad en el tratamiento quirúrgico de la EII entre los centros españoles, objetivandose diferencias en la tasa de complicaciones en pacientes con cirugías de alta complejidad. La calidad de vida mejoró de forma global con el tratamiento quirúrgico.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic relapsing disease with increasing prevalence throughout the world that considerably impacts patients’ physical health, social functioning and quality of life.1,2 Some 50%–80% of patients with Crohn's disease (CD) will need at least one surgical intervention during their lives,2–7 as will around 20% of patients with Ulcerative Colitis (UC).

IBD surgery is complex and exposes patients to an increased risk of perioperative complications due to the interaction between the disease, surgery, and medical treatment.8 In other countries, several multicenter studies have been conducted on the outcomes of surgical treatment of IBD.9–15 In Spain, however, such publications have focused on the medical treatment and quality of life perceived by patients with IBD.16,17 In 2016, a cross-sectional survey was conducted on the reality of the surgical treatment of IBD,18 which showed great variability in the organization and surgical treatment of patients with IBD at different types of hospitals and in the different regions (autonomous communities) of Spain. Following this survey, a nationwide prospective multicenter registry was launched by the Inflammatory Disease and Surgery Registry Group (Grupo Registro de Enfermedad Inflamatoria y Cirugía, or REIC) in order to evaluate the situation of surgical treatment for IBD in Spain. We present the initial results of the study, which analyzes the institutional, demographic and perioperative variables of IBD patients treated surgically at Spanish medical centers after one year of follow-up.

MethodsStudy designThe “REIC: Registry of Inflammatory Disease and Surgery” study is a prospective, nationwide, multicenter, observational study developed in accordance with the STROBE guidelines.19 Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committees at the promoting medical centers, and each participating hospital assigned a main investigator to work in contact with the local ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. The participating hospitals had been invited to participate directly as well as through an open call that had been included in the Spanish Association of Surgeons newsletter and disseminated on social media for 2 months.

Inclusion criteria and data collectionOur study included all patients over 16 years of age who had undergone surgery for CD, UC or primary and recurrent indeterminate colitis (IC) between June 1, 2018 and May 31, 2021. Surgery was defined as one of 3 types: scheduled, deferred urgent (any surgical intervention that was scheduled during hospitalization due to complication of the disease), and urgent or emergency. Participating hospitals were classified by the number of beds (small <300, medium 300–500, and large >500 beds) and by the volume of IBD operations per year (low <10 procedures, moderate 11–20 procedures, and high >20 procedures). The surgeries were classified according to their complexity. “Low complexity” procedures included: ileocecal resection, subtotal colectomy and small intestine resection; anal exploration under anesthesia (EABA), drainage of abscesses and placement of setons. The remaining procedures were considered “high complexity”.8,2 In order to reduce selection bias, all consecutive patients from each study center were systematically included. The inclusion of patients was anonymous and anonymized, and reminders were established for the main investigator of each center to avoid bias due to loss to follow-up.

The data were stored in the anonymized and encrypted online database, hosted on Fundanet. The study analyzed hospital data, patient demographics, medical history and current treatment, baseline and preoperative nutritional status, as well as surgical details and surgeon specialization. Both 60 days and one year after surgery, perioperative morbidity and mortality, recurrence and quality of life were evaluated using the validated IBDQ-9 questionnaire,20 the result of which is expressed on a scale from 0 (worst quality of life) to 100 (best quality of life).

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were described as frequencies and percentages and compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were described as mean (standard deviation) or median (range) according to their distribution and compared using the Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test when presenting a symmetric or asymmetric distribution, respectively. For the statistical analysis, the IBM Corporation SPSS (v22.0) software was used.

ResultsA total of 1134 patients were included from 77 participating hospitals, 61% (47) of which were large hospitals, 24.6% (19) medium and 14.4% (11) small. In terms of the volume of annual IBD surgeries, 30 hospitals (35.5%) had high volumes, 20 (25.9%) moderate and 27 (38.6%) low volumes.

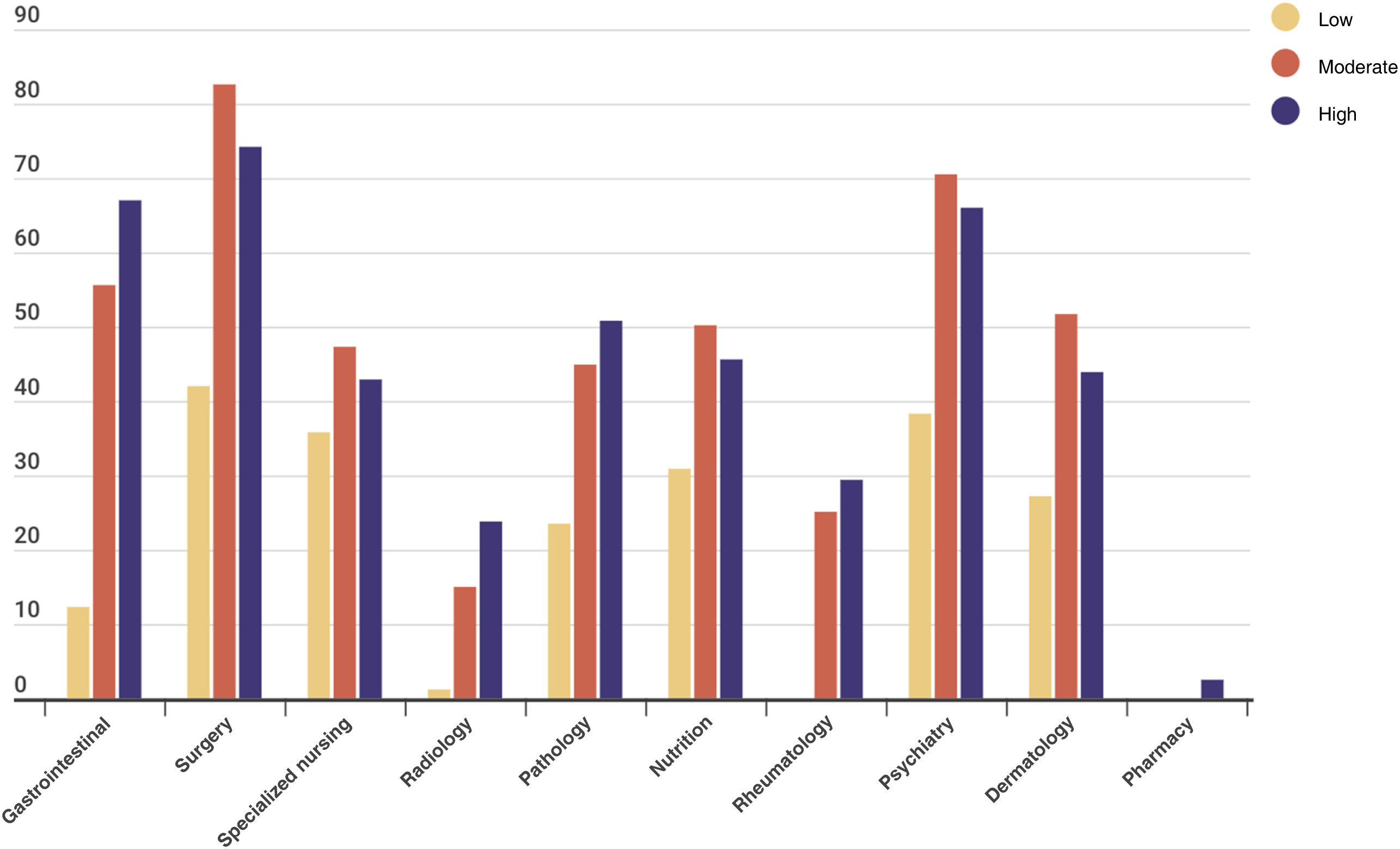

Preoperatively, 81.6% (898) of the patients were evaluated by a multidisciplinary IBD committee (83% of patients with deferred emergency, and 78.8% of elective surgery patients), with no differences among hospitals of different volumes for scheduled patients (P = .234). Fig. 1 specifies the composition of the committees at the different medical centers. The average waiting time from surgical indication to intervention was 2.09 ± 2 months for scheduled patients (2.41 ± 2.4 for abdominal surgery, and 1.41 ± 1.9 for proctological surgery), with no differences among the types of medical centers (P > .05), although it was higher for patients with a surgical history compared to patients with de novo diagnosis (2.86 ± 3 months vs 1.98 ± 2.14 months) (P < .001).

The study population was comprised of 54.2% (614) males and 45.8% (520) females. The majority were ASA II and III (63.9% and 26.4%, respectively). A total of 888 patients (78.3%) were diagnosed with CD, 229 UC (20.2%) and 17 patients IC (1.5%). Over half (52.9%; 600) of the patients had previously undergone surgery, most frequently for abdominal surgeries and perianal surgeries due to CD (Table 1).

Characteristics of patients registered according to IBD type.

| CD (n = 888) | UC (n = 229) | IC (n = 17) | Total (n = 1134) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Male | 455 (51.3) | 146 (64) | 13 (70.6) | 614 (54.2) | ||

| Female | 433 (48.7) | 83 (36) | 4 (29.4) | 520 (45.8) | ||

| Age(years) | Mediana [Q1;4] | 45 [35.46] | 50 [49.59] | 53 [36.59] | 0.03 | |

| ASA | n (%) | 0.337 | ||||

| I | 77 (8.6) | 18 (8) | 1 (5.9) | 96 (8.5) | ||

| II | 580 (65.3) | 135 (58.9) | 10 (58.8) | 725 (63.9) | ||

| III | 222 (25.1) | 70 (30.8) | 6 (35.3) | 298(26.4) | ||

| IV | 9 (0.9) | 6 (2.2) | 15 (1.2) | |||

| Smoking | n (%) | 354 (39.9) | 40 (17.5) | 5 (29.4) | 399 (35.2) | 0.001 |

| BMI | n (%) | 0.229 | ||||

| Normal | 603 (67.9) | 132 (57.6) | 12 (73.3) | 747 (65.8) | ||

| Overweight | 210 (23.7) | 72 (31) | 3 (20) | 285 (25.1) | ||

| Obese I | 57 (6.4) | 23 (10.3) | 1 (6.7) | 81 (7) | ||

| Obese II | 12 (1.4) | 2 (1.1) | 24 (2.05) | |||

| Obese III | 6 (0.6) | 6 (0.05) | ||||

| DM | n (%) | 277 (31.2) | 75 (32.8) | 9 (52.9) | 361 (31.8) | 0.154 |

| Pregnancy | n (%) | 81 (9.1) | 12 (5.2) | 2 (11.8) | 95 (8.4) | 0.147 |

| Cancer history | n (%) | 37 (4.2) | 11 (4.8) | 1 (5.9) | 49 (4.3) | 0.869 |

| Abdominal surgery | n (%) | 688 (78) | 181 (20.5) | 13 (1.5) | 882 | |

| Simple | n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Ileocecal resection | 387 (56.3) | 0 | 3 (23.1) | 390 (44.2) | ||

| Segmental bowel resection | 151 (21.9) | 6 (3.3) | 3 (23.1) | 160 (18.1) | ||

| Total/subtotal colectomy | 29 (4.2%) | 80 (44.2) | 2 (15.4) | 111 (9.6) | ||

| Complex | n (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Strictureplasty | 13 (1.9) | 1(0.6) | 0 | 14 (1.6) | ||

| Ileostomy closure | 20 (2.9) | 9 (5) | 0 | 29 (3.3) | ||

| Segmental colectomy | 60 (8.7) | 11 (6.1) | 2 (15.4) | 73 (8.3) | ||

| Reservoir excision | 0 | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Hartmann | 7 (1) | 6 (3.3) | 1 (7.7) | 14 (1.6) | ||

| Anterior resection | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Proctocolectomy | 16 (2.3) | 23 (12.7) | 1 (7.7) | 40 (4.5) | ||

| Restorative proctocolectomy | 2 (0.3) | 13 (12.7) | 0 | 15 (1.7) | ||

| Restorative proctectomy | 0 | 16 (8.8) | 0 | 16 (1.8) | ||

| Proctectomy + end ileostomy | 2 (0.3) | 13 (7.2) | 1 (7.7) | 16 (1.8) |

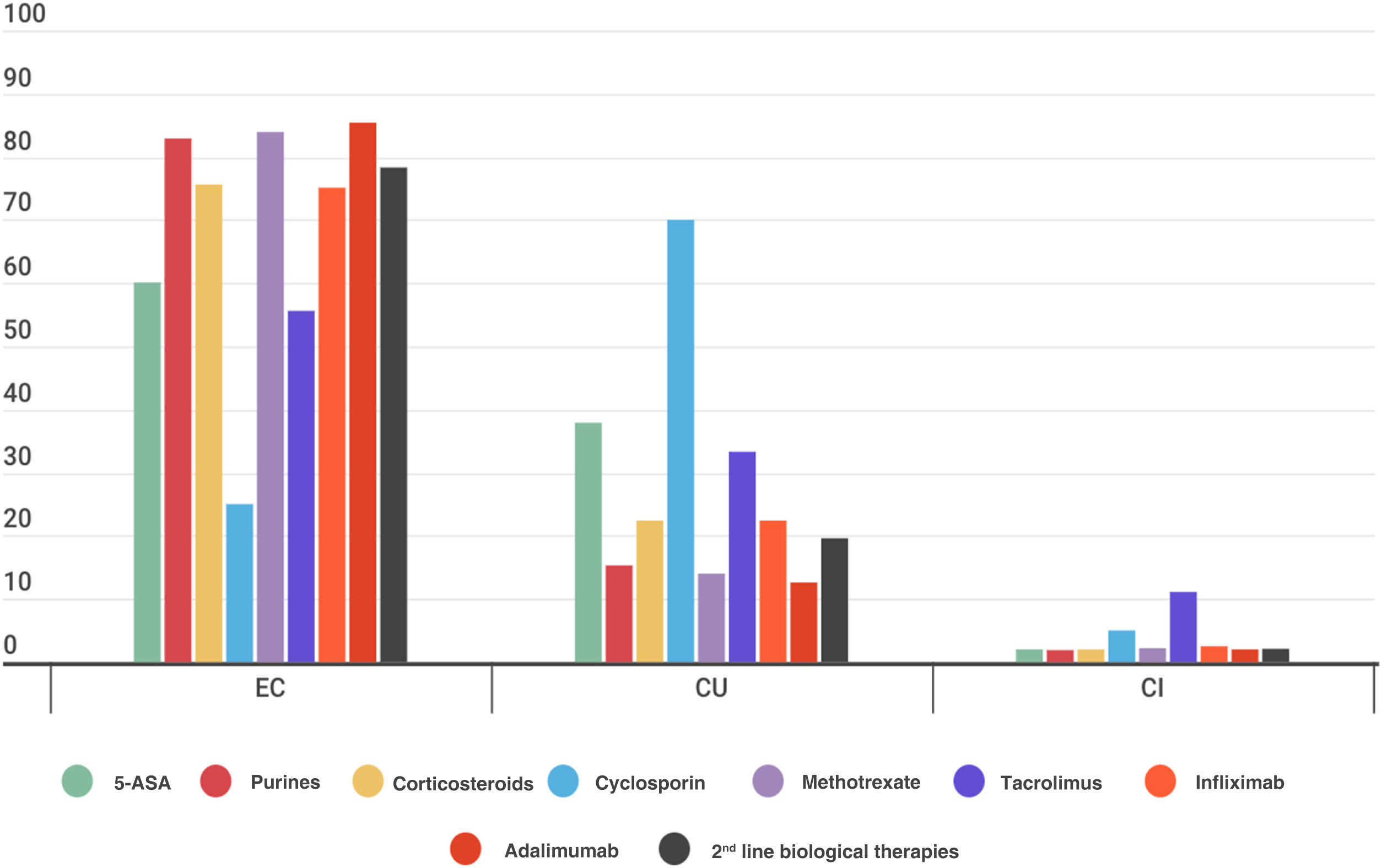

A total of 950 patients had preoperative imaging studies, with a predominance of colonoscopies (80.5%; 865), followed by MRI-enterography (40.4%; 384), CT scans (25.7%; 244) and abdominal ultrasound (20.6%; 196). Most patients (84%; 953) were prescribed medication prior to surgery. The specific preoperative medical treatment for IBD according to disease type is represented in Fig. 2. The numbers of patients with enhanced biological treatments (infliximab and adalimumab) were similar among the hospitals (18.5%, 17.4% and 14.9% at low-, moderate- and high-volume centers, respectively; P = .51). However, more patients did undergo surgery with an enhanced corticosteroid strategy in low- and high-volume hospitals than in moderate-volume centers (7.1% vs 25% and 27.9%, respectively; P < .001).

A total of 1169 surgeries were recorded, 71.4% of which were elective, 11.3% deferred urgent, and 17.3 urgent. Out of the total, 1009 (86.31%) were performed at high-volume centers, 106 (9.08%) moderate-volume centers, and 54 (4.61%) low-volume centers, with no significant differences in the number of scheduled or urgent deferred surgeries according to the type of medical center. Colorectal surgeons were the primary surgeons in more than 70% of the procedures. The main surgical indications in CD were obstruction (31.8%) and intestinal fistula (21.7%), while in UC it was severe flare-up.

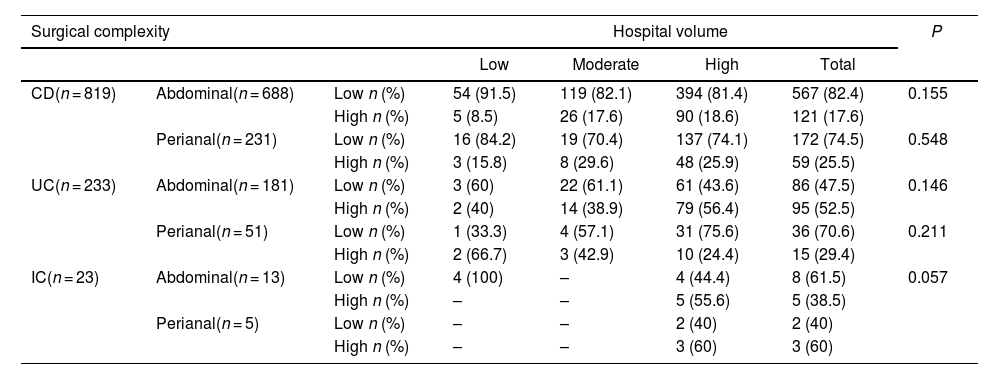

Out of the 688 abdominal surgeries for CD, the majority (82.4%) were low complexity, presenting a similar distribution among hospitals. In UC, 181 abdominal surgeries were recorded, 52.5% of which were high complexity, and the majority had been performed at high-volume centers (83.2%). Lastly, 13 IC (1.48%) were recorded, the majority of which were highly complex and performed at high-volume hospitals.

Regarding the 287 perianal surgeries performed, 231 procedures (80.48%) were performed in patients with CD, 172 (74.5%) of which were deemed low complexity. The 59 high-complexity surgeries were performed mainly at high- and medium-volume hospitals (48 [81.4%] and 8 [13.6%] procedures, respectively; P > .05). In UC, a total of 51 perianal surgeries were performed, 36 (70.6%) of which were low complexity, and all had been performed at high-volume medical centers; the same held true for IC patients (n=5), (P > .05). The surgery types and type of IBD are correlated in Table 2.

Classification of surgeries performed in patients with IBD in the Spanish registry, classified by complexity and hospital volume.

| Surgical complexity | Hospital volume | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | Total | ||||

| CD(n = 819) | Abdominal(n = 688) | Low n (%) | 54 (91.5) | 119 (82.1) | 394 (81.4) | 567 (82.4) | 0.155 |

| High n (%) | 5 (8.5) | 26 (17.6) | 90 (18.6) | 121 (17.6) | |||

| Perianal(n = 231) | Low n (%) | 16 (84.2) | 19 (70.4) | 137 (74.1) | 172 (74.5) | 0.548 | |

| High n (%) | 3 (15.8) | 8 (29.6) | 48 (25.9) | 59 (25.5) | |||

| UC(n = 233) | Abdominal(n = 181) | Low n (%) | 3 (60) | 22 (61.1) | 61 (43.6) | 86 (47.5) | 0.146 |

| High n (%) | 2 (40) | 14 (38.9) | 79 (56.4) | 95 (52.5) | |||

| Perianal(n = 51) | Low n (%) | 1 (33.3) | 4 (57.1) | 31 (75.6) | 36 (70.6) | 0.211 | |

| High n (%) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (42.9) | 10 (24.4) | 15 (29.4) | |||

| IC(n = 23) | Abdominal(n = 13) | Low n (%) | 4 (100) | – | 4 (44.4) | 8 (61.5) | 0.057 |

| High n (%) | – | – | 5 (55.6) | 5 (38.5) | |||

| Perianal(n = 5) | Low n (%) | – | – | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | ||

| High n (%) | – | – | 3 (60) | 3 (60) | |||

A total of 115 stomata were recorded in CD, mainly end ileostomies (66.1%), end colostomies (25.2%), lateral ileostomies (7%), and lateral colostomies (1.7%). The surgeries with a higher percentage of stomata were segmental colectomies and segmental resections of the small intestine. In UC, 143 stomata were recorded, the majority of which were end ileostomies (103; 72%). In both pathologies, no significant differences were found among the hospital types, even when complex surgeries were specifically evaluated.

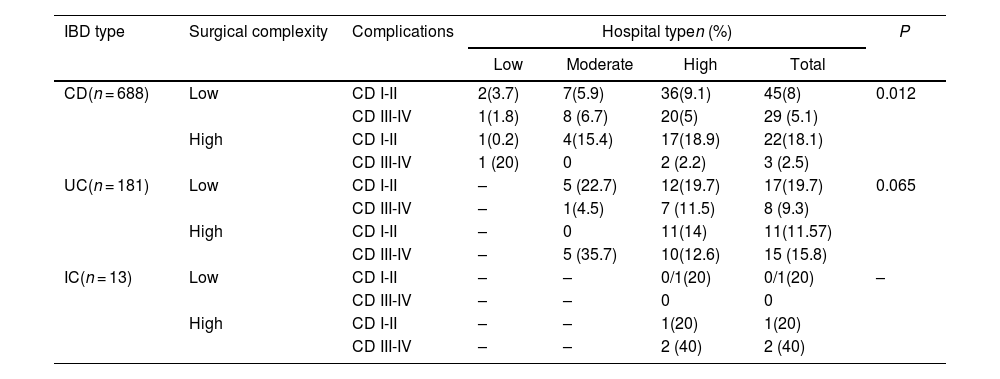

Postoperative complications and recurrenceThe overall rate of postoperative complications was 16% (187); 63.6% (119) were minor complications (Clavien-Dindo I-II), and 36.4% (68) were major complications (Clavien-Dindo III-V), with no global differences among hospitals (P > .05). In CD, the percentage of major complications in highly complex surgeries at moderate- and high-volume hospitals was lower than at low-volume hospitals (0 and 2.2% vs 20%, respectively) (P = .012). In UC, these differences were also observed (12.6 and 15.8 vs 35.7), although they were not statistically significant (P = .06).

Over the course of the one-year follow-up, 9 deaths were recorded: 7 patients with CD (4 and 3, at moderate-volume and high-volume hospitals, respectively); and 2 with UC (one moderate-volume and one high-volume hospital) (Table 3).

Complication in abdominal surgery by type of complexity and hospital volume.

| IBD type | Surgical complexity | Complications | Hospital typen (%) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | Total | ||||

| CD(n = 688) | Low | CD I-II | 2(3.7) | 7(5.9) | 36(9.1) | 45(8) | 0.012 |

| CD III-IV | 1(1.8) | 8 (6.7) | 20(5) | 29 (5.1) | |||

| High | CD I-II | 1(0.2) | 4(15.4) | 17(18.9) | 22(18.1) | ||

| CD III-IV | 1 (20) | 0 | 2 (2.2) | 3 (2.5) | |||

| UC(n = 181) | Low | CD I-II | – | 5 (22.7) | 12(19.7) | 17(19.7) | 0.065 |

| CD III-IV | – | 1(4.5) | 7 (11.5) | 8 (9.3) | |||

| High | CD I-II | – | 0 | 11(14) | 11(11.57) | ||

| CD III-IV | – | 5 (35.7) | 10(12.6) | 15 (15.8) | |||

| IC(n = 13) | Low | CD I-II | – | – | 0/1(20) | 0/1(20) | – |

| CD III-IV | – | – | 0 | 0 | |||

| High | CD I-II | – | – | 1(20) | 1(20) | ||

| CD III-IV | – | – | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | |||

One year after the intervention for CD, a total of 142 recurrences were recorded: 63 clinical (44.4%), 61 endoscopic (43%), 16 radiological (11.3%) and 2 surgical (1.4%), with no significant differences found among study centers (P > .05).

Quality of life related to IBDQuality of life was analyzed by administering the validated IBDQ-9 questionnaire at baseline as well as 60 days and one year after surgery. In patients with CD (n = 343), quality of life improved in global scores 60 days and 12 months after the operation versus preoperative scores (+13.12 ± 0.59 and +4 ± 0.63; P < .001). In patients with UC (n = 87), quality of life improved in global scores 60 days post-op, and a trend towards improvement was observed 12 months post-op, in both cases compared to preoperative scores (+9.17 ± 1.38, P < .001; +1.71 ± 1.43, P > .05). The scores worsened among the 60-day and 12-month surveys (−8.5 ± 0.41 and −8.8 ± 0.85, P < .001) in CD and UC, respectively.

DiscussionThe data from the REIC registry demonstrate that there is no unified path for IBD surgical care in our country, and all types of surgeries are performed at hospitals with different surgical volumes. As a result, there are variable rates of complications and differences among the different regions of Spain, as reported by previous studies.18 Action plans and criteria for referral to specialized medical centers have been established in oncology patients,21 yet these are not being implemented in IBD, even though they have been recommended in quality standards.8,14,15,22 The results of this study suggest that more complex patients could benefit from being treated at hospitals with higher volumes, as reflected in the complication rate. However, for other points our country is within the recommended quality standards,8,14,15,22 such as the presentation of patients who are candidates for surgical treatment before a multidisciplinary committee (81.6% of patients) as well as a stipulated waiting time of less than 4.5 months from diagnosis to surgery,14 which was 8 weeks in our sample.

The characteristics of our patient cohort are similar to those of other countries, with a high rate of patients treated with biological drugs at all study centers. However, second-line or enhanced drugs were used more frequently in patients undergoing surgery at higher volume hospitals, which seems to indicate the presence of patients who were more refractory to treatment or more complex in these centers. As described by the American CD registry,8 the most frequent surgical procedures were ileocecal resections (44.2%) and subtotal colectomies (12.6%), as well as surgeries considered low complexity in our study that, unlike the American one, are carried out in all types of hospitals (with low, moderate, and high volumes).

Another standard described for quality IBD surgery is in-hospital mortality.22 In our study, mortality was very low (0.8%) in both CD and UC, which reflects that, in our setting, mortality is not an optimal reference to compare results among types of medical centers.15 In contrast, the rate of major complications in complex surgeries in our study was lower at hospitals with high volumes of CD and UC (2.2% and 15.8%, respectively) compared to lower-volume centers (20% and 35.7%), although the differences were not significant. This suggests that patients with surgical indication for certain highly complex procedures should be operated on at higher volume hospitals.23,24 In Spain, there is no legislative regulation that requires more complex patients to be referred to larger hospitals, unlike what happens in other countries, such as the Italian system.15 International Guidelines8,14,25 also recommend access to a coordinated medical-surgical team with a surgeon specially dedicated to IBD and that, if such a surgeon is not available, patients should be referred to medical centers with greater experience and volume.26 Furthermore, it is recommended that all patients who require surgery be optimized prior to surgery in terms of their medication and physical condition; also, they should be included in an informational and stoma therapy program in order to improve the quality of life of ostomy patients, which are data not analyzed in our study.14

An important finding of this study is the improved quality of life of patients after surgery compared to their baseline situation, with a slight worsening after one year that was still superior to the preoperative results. In line with studies from other countries, this demonstrates the importance of surgery as part of the treatment for our patients.27

The main strength of this study is the large, prospective cohort of patients and a larger number of hospitals than most European national registries. Furthermore, the participation of a similar number of hospitals with different surgical volumes makes the results more representative when compared to other registries, such as the American or Italian studies of large hospitals, which probably explains the differences in the number of complications according to the type of hospital.8,15 In addition, registries offer data from a real-world context, not from controlled research like in clinical trials; therefore, the results obtained could be inferred to the entire community.28 However, in addition to follow-up bias due to loss and abandonment of long-term data entry (as demonstrated by the decrease in quality of life data in the present study in some 38% of patients), registries with voluntary participation entail a risk of selection bias, which could be considered a limitation of our study. Likewise, the classification of surgeries as “low” or “high complexity” could be highly variable depending on the case and type of surgery. Also note that, as the registration period coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, we needed to make the data collection time more flexible.

Prospective national and international registries should be implemented in clinical practice as part of improvement programs sponsored by scientific societies, as they help maintain quality standards and improve poor results. The REIC registry is a first step to work towards these objectives in Spain and is similar to initiatives in other countries, such as Great Britain, where the ACPGBI has recently developed a new online registry: IBD Surgery (IBS-S).25 There is still room to improve the quality of the surgical care we offer our IBD patients, including the creation of referral circuits for more complex patients. Nevertheless, the high level of participation obtained in our study demonstrates the willingness to continue working towards improving the surgical care we offer patients with IBD in our country.

ConclusionsData from the REIC registry demonstrate that the surgical treatment of IBD is heterogenous among Spanish hospitals, describing more complex patients and procedures at high-volume hospitals. While surgeries classified as simple present no differences in the rate of complications or waiting times depending on the hospital type, highly complex surgeries have lower morbidity rates when performed at high-volume medical centers. Overall, quality of life improved significantly after surgery. It is necessary to continue implementing registries to evaluate and improve the quality of IBD surgery in Spain.

Conflict of interestNone.

This study received a research grant from Takeda Farmaceutica S.A. (IISR-2017-101978).

The authors would like to thank all participants and coauthors of this study for their work and effort in data collection.

J. M. Enriquez-Navascues, G. Elorza-Echaniz (Hospital Universitario de Donostia, San Sebastián); J. Die Trill, J. Ocaña Jimenez (Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid); D. Moro-Valdezate, C. Leon-Espinoza (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, Valencia); V. Primo-Romaguera, J. Sancho-Muriel (Hospital Universitario y Politécnico de La Fe, Valencia) ; I. Pascual Migueláñez, J. Saavedra (Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid); P. Penín de Oliveira, F. Meceira Quintian (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña, A Coruña); M. Carmona Agúndez, I. M. Gallarín Salamanca (Hospital Universitario de Badajoz, Badajoz); R. Lopez de los Reyes, E. Vives Rodriguez (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ferrol, Ferrol); A. Navarro-Sánchez, I. Soto-Darias (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular-Materno Infantil, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria); I. Monjero Ares, M. I. Torres García (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Lugo, Lugo); I. Aldrey Cao (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense, Ourense); E. M. Barreiro Dominguez, S. Diz Jueguen (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Pontevedra, Pontevedra); J. C. Bernal Sprekelsen, P. Ivorra García-Moncó (Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia); V. Vigorita, M. Nogueira Sixto (Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro, Vigo); C. Martín Dieguez, M. López Bañeres (Hospital Arnau de Vilanova, Valencia); T. Pérez Pérez, E. Añón Iranzo (Hospital Lluís Alcanyis, Xátiva); R. Vázquez-Bouzán, E. Sánchez Espinel (Hospital Ribera Provisa, Vigo); I. Alberdi San Roman, A. Trujillo Barbadillo (Hospital de San Eloy, Barakaldo); R. Martínez-García, F. J. Menárguez Pina (Hospital de la Vega Baja, San Bartolomé); R. Anula Fernández, J. A. Mayol Martínez (Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid); A. Romero de Diego, B. De Andres-Asenjo (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, Valladolid); N. Ibáñez Cánovas, J. Abrisqueta Carrión (Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, El Palmar); M. Estaire Gómez, R. H. Lorente Poyatos (Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real, Ciudad Real); D. Julià-Bergkvist, N. Gómez-Romeu (Hospital Universitario Doctor Josep Trueta, Girona); M. Romero-Simó, F. Mauri-Barberá (Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis, Alicante); A. Arroyo, M. J. Alcaide-Quiros (Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche); J. V. Hernandis Villalba, J. Espinosa Soria (Hospital General Universitario de Elda, Elda); D. Parés, J. Corral (Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona); L. M. Jiménez-Gómez, J. Zorrilla Ortúzar (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid); I. Abellán Morcillo, A. Bernabé Peñalver (Hospital General Universitario Los Arcos del Mar Menor, Pozo Aledo); P. A. Parra Baños, J. M. Muñoz Camarena (Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía, Murcia); L. Abellán Garay, M. Milagros Carrasco (Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía, Cartagena); M. P. Rufas Acín, D. Ambrona Zafra (Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova, Lleida); M. H. Padín Álvarez, P. Lora Cumplido (Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes, Gijón); L. Fernández-Cepedal, J. M. García-González (Hospital Universitario de Cruces, Barakaldo); E. Pérez Viejo, D. Huerga Álvarez (Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada, Fuenlabrada); A. Valle Rubio, V. Jiménez Carneros (Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Getafe); B. Arencibia-Pérez, C. Roque-Castellano (Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria); R. Ríos Blanco (Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina, Madrid); B. Espina Pérez, A. Caro Tarrago (Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII, Tarragona); R. Saeta Campo, A. Illan Riquelme (Hospital Marina Baixa, Villajoyosa); E. Bermejo Marcos, A. Rodríguez Sánchez (Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, Madrid); C. Cagigas Fernández, L. Cristóbal Poch (Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander); M. V. Duque Mallen, M. P. Santero Ramírez (Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza); M. d. M. Aguilar Martínez (Hospital Universitario Poniente, El Ejido); A. Moreno Navas, J. M. Gallardo Valverde (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba); E. Choolani Bhojwani, S. Veleda Belanche (Hospital Universitario Río Hortega, Valladolid); C. R. Díaz-Maag, R. Rodríguez-García (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca); A. Alberca Páramo, N. Pineda Navarro (Hospital Universitario San Agustín, Linares); E. Ferrer Inaebnit, N. Alonso Hernández (Hospital Universitario Son Espases, Palma); M. Ferrer-Márquez, Z. Gómez-Carmona (Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas, Almería); M. Ramos Fernandez, E. Sanchiz Cardenas (Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga); J. Valdes-Hernandez, A. Pérez Sánchez (Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Sevilla); M. Labalde Martínez, F. J. García Borda (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid); S. Fernández Arias, M. Fernández Hevia (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo); T. Elosua González, L. Jimenez Alvarez (Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León, León).