In this age of an avalanche of data, on a personal level it is very complex to manage the volume of information that is produced in each specialty or super specialty within surgery. We can almost say that it is not possible for individual health care professionals to guarantee that their decisions are based on the information from all the latest and most reliable research knowledge. We need the most complete and reliable information to guide clinical and therapeutic decision-making; decisions that, without knowledge of previous conditions, may be random and compromised.

Systematic review (SR) has become a fundamental tool in the practice of evidence-based surgery, providing a systematic and quantitative approach to synthesizing results from multiple studies.1 In this methodology letter, we shall use an example as an illustration to go through each of the steps needed to carry out a systematic review.

Formulation of the research questionAs an example of a research question for a systematic review with meta-analysis, we consider the following: “Is the robotic-assisted laparoscopic technique (RLT) more effective and safer than the conventional laparoscopic technique (CLT) for inguinal hernia repair?”. This question focusses on comparing the two surgical techniques in terms of hernia recurrence rates, postoperative complications, recovery time, and patient’s quality of life (patient reported outcome). Clarity in the formulation of the question is crucial to guide the search and selection of relevant studies2 and can also contribute to determining the applicability of the results in clinical practice. In undertaking an SR, it is usually a requirement by the editors of the main scientific journals to produce a protocol and publish it in a repository such as the PROSPERO3 platform. This reduces the risk that authors will alter their outcome measures or comparisons after the fact.4

Study search and selectionOne of the main characteristics of systematic reviews is the search and identification of the maximum number of studies related to the research question.

An exhaustive search must be run through databases such as MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Library or other specific databases where we are able to identify studies related to the review question. A resource to help in the construction of the electronic search strategy is to break down the question into the four elements of the acronym PICO (P = patient, I = intervention, C = comparator, O = Outcome, which translates as outcome measurements).5 In the example selected, you would proceed by selecting search terms for each element. The terms may be from a thesaurus (such as MeSH from Medline) and also from free text. Combining both appropriately will provide a more optimal balance between the sensitivity and specificity of the electronic search (Table 1).

Generally, terms in the same column are combined using the Boolean operator OR and the combination of terms between columns using the Boolean operator AND. In the search it will also be important to consider what type of studies will be included in the SR, whether they are clinical trials, observational studies or other designs. It is a good practice to provide all the details from the search of the literature so that this can be reproduced by another researcher.6 The PRISMA flowchart should be incorporated into any systematic review to show the number of studies identified, excluded and included.7 For the electronic search in the databases, it is advisable to have a professional documentalist.

Assessment of the quality of studiesAnother extremely important step in conducting an SR is the assessment of the quality of the studies included. To this end, there are multiple standardised tools that enable mainly the risk of bias of each of the studies to be assessed. The aspects to be evaluated will be related to the study design and specific elements such as the randomisation process in the case of randomised clinical trials. At this stage, the colloquial phrase “garbage in, garbage out” must be kept in mind. In other words, the quality of the result is determined by the quality of the individual studies.

Data extraction and synthesisThis stage refers to the retrieval of the relevant data from each individual study. This covers from a study identifier such as, for example, the bibliographical reference, to the data from the variables that are analysed in the review. Examples of these would be the number of relapses, complications, quality of life observed in each study, and for each of the groups of patients where conventional robotic or laparoscopic surgery has been performed. It is absolutely recommended that the data retrieval for each study be done by at least two people, and a third person acts as a referee in case of discrepancies in the data retrieved.

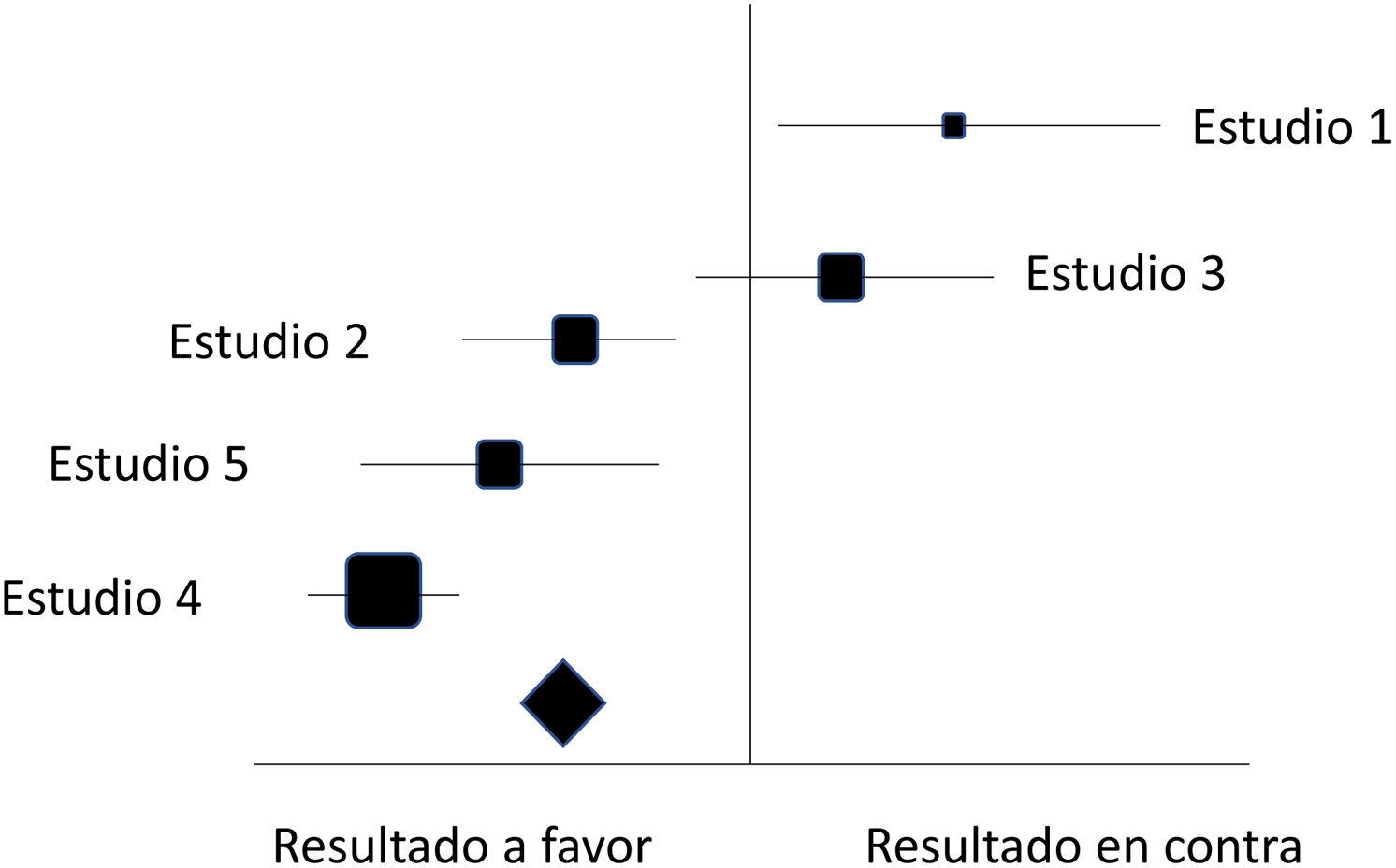

Statistical analysisIt is not possible to carry out quantitative analysis using the statistical technique of meta-analysis in all SRs. However, when the individual studies provide sufficient data and there are no notable differences with respect to the characteristics of the patients, the application of the intervention, the outcome measures evaluated (i.e. there is no significant clinical heterogeneity) it is possible to combine these to obtain a numerical estimate of the effect of each intervention, thus obtaining a global effect estimator for each outcome of relevance: for example, for the number of relapses, complications or quality of life. In addition to numerical quantification, meta-analysis can also include a resource termed “forest plot” that provides visual interpretation of the results (Fig. 1).

Graphical representation of a meta-analysis using a forest plot. In this case, a meta-analysis with 5 clinical trials is illustrated in a simulated form. The studies are numbered according to the year of publication, with 1 being the oldest and 5 the most recent. The horizontal line in each study represents the confidence interval. The size of the box corresponds to the “weight” of the study in this meta-analysis. The rhombus illustrates the overall effect corresponding to all 5 studies. In this case the rhombus is located in the “outcome in favour” area, indicating that the new intervention has a favourable effect for the outcome measure assessed: for example, a reduction in the number of postoperative complications.

Heterogeneity between studies can be explored, for example, through subgroup analyses, considering factors such as patients' age and health condition, hernia size and location, and surgeon’s experience. This approach helps to identify whether specific conditions or techniques influence the results. Proper management of heterogeneity is crucial to ensure that the conclusions of the meta-analysis are applicable to a wide range of clinical contexts and are not misinterpreted or inappropriately generalised. There are some useful indices, such as the Higgins index, which make it possible to quantify the degree of heterogeneity.8

Publication of resultsResults should be presented clearly and concisely, using tables and graphs, if possible (such as forest plots), to illustrate comparisons between the surgical techniques analysed. At the time of publication of the results, a large number of journals were following the PRISMA guidelines for the publication of SRs, ensuring transparency and consistency in the presentation of the data.9

Please cite this article as: Garcia-Alamino JM, López-Cano M. Etapas para la realización de una revisión sistemática con metaanálisis. Cir Esp. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2024.05.010