The objective of this study is to analyze our experience in the use of sentinel node biopsy (SNB) in melanoma and identify the predictive factors of positive SNB and multiple drainage.

Materials and methodsRetrospective study of patients who underwent SNB for melanoma between August of 2000 and February of 2013.

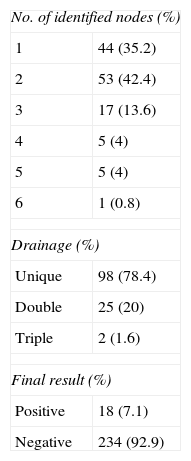

ResultsSNB was performed in 125 patients with a median of age of 55.6 (±15) years. The anatomic distribution was: 44 (35.2%) in legs, 24 (19.2%) in arms, 53 (42.4%) trunk and 3 (2.4%) in head and neck. The median Breslow index was 1.81 (0.45–5). Between 1 and 6 nodes were isolated. The drainage was unique in 98 (78.4%) and multiple in 27 (21.6%). The trunk was the localization of 25 (92.6%) nodes with multiple drainage. The definitive result of sentinel node (SN) was positive in 18 cases (7.1%). Breslow thickness (P=.01) was statistically significant predictor of a positive SNB.

ConclusionsThe SNB allows patients to be selected for lymphadenectomy. Melanoma of the trunk was the principal location of multiple drainage predictors. The only predictive factor of positive SNB was Breslow thickness.

El objetivo del estudio es analizar nuestra experiencia en el uso de la biopsia del ganglio centinela (BGC) en el melanoma y determinar la existencia de factores predictores de resultado positivo y de drenaje múltiple.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo y analítico de aquellos pacientes a los que se les realizó BGC por melanoma, en el período entre agosto de 2000 y febrero de 2013.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 125 pacientes con una media de edad de 55,6 (±15) años. La distribución anatómica de los ganglios centinelas (GC) fue: 44 (35,2%) en miembros inferiores, 24 (19,2%) en miembros superiores, 53 (42,4%) en tronco y 3 (2,4%) en cabeza y cuello. La mediana del índice de Breslow fue de 1,81 (0,45-5). El número de ganglios aislados fue entre 1 y 6, siendo en 98 casos (78,4%) de localización única y en 27 (21,6%) múltiple, de los que 25 (92,6%) se localizaron en el tronco. El estudio definitivo de la BGC fue positivo en 18 casos (7,1%), siendo el factor predictivo relacionado el espesor tumoral (p = 0,01).

ConclusionesLa BGC seleccionó de forma adecuada a los candidatos a linfadenectomía. El melanoma de tronco fue la principal localización de drenaje múltiple. El único factor predictor de resultado positivo del GC fue el espesor tumoral.

The incidence of melanoma has increased rapidly in recent years. Given that it affects young people with significant mortality rates, it is a worldwide public health problem.1–3

In 1992, Morton et al. published the first paper on using sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) for melanoma. The procedure is based on the hypothesis that lymphatic metastases follow an orderly, sequential and non-random progression. Therefore, a first nodal drainage station sentinel lymph node (SLN) examination would safely reflect the status of the remaining regional lymph nodes.2,4 It is a minimally invasive method to identify patients with occult lymph node metastasis and avoid lymphadenectomy in a large number of patients without lymph node involvement.4

SLNB provides important information for tumor staging to detect micro-metastases.5 It is prescribed for patients with localized disease (stages I–II). Patients with melanoma less than 0.75mm have a 1% risk of lymph node involvement, and it is not recommended for them.3 Other authors advocate including patients with a thickness <1mm with factors related to increased micro-metastases risk such as primary tumor ulceration, mitotic index ≥1mm–2 or Clark level IV/V.5

Lymphoscintigraphy has changed the traditional Sappey lymphatic drainage concept, which divides the anatomy into 4 quadrants using 2 perpendicular lines through the umbilicus, which marks the theoretical boundary that lymphatic drainage of lesions in these quadrants could not penetrate.2 Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy has demonstrated high discordance between anatomic location and actual drainage flow, especially in the thorax; this proof is essential for correct SLN localization.3

This study aims to analyze our experience in using SLNB for melanoma and determine the existence of positive outcome and multiple drainage predictors.

Materials and MethodsThis is a retrospective, observational study of patients who underwent SLNB for melanoma in our center between August 2000 and February 2013. In our center, SLNB is conducted on patients referred from other centers that lack the procedure; therefore, we failed to obtain 100% of the information in some sections.

Patient data were obtained by reviewing medical records. Inclusion criteria were: stage Ia with risk factors (satellitosis, vascular invasion, ulceration, Clark IV–V, tumor regression >75% or incomplete excision with deep affected margin), Ib, IIa, IIb and IIc (in good general condition). Lymph node involvement was ruled out by examination and if in doubt, histological analysis after puncture. All cases were included for SLNB after being discussed in a multidisciplinary committee. Lymphadenectomy was performed subsequently on patients with SLN metastasis.

The pathological study protocol included deferred SLNB, 4μ serial sections; 4 cuts were made at each level: 2 for hematoxylin-eosin (HE) stain, and 2 for S-100 protein and HMB-45 immunohistochemistry (IHC), until exhausting the sample.

Lymph gammagraphy analysis was conducted with 1.5mCi of 99m Tc-albumin nanocolloid by perilesional injection on the day of surgery. After 5min, planar images of antero-posterior projections of the groin, abdomen and arms were obtained. In the event of positivity, lateral projection was performed of the groin and abdomen, plus oblique projection in the axilla. The same serial analysis was performed every 15min until its positivity. In the operating room, SLN was identified by manual gamma probe.

Variables analyzed were age, sex, personal history, primary melanoma characteristics, location, studying BANS location independently (back: upper back, arm: back of the arm, neck: back and side of neck, scalp: rear and top of the scalp area), Breslow tumor thickness and SLN.

Data were analyzed with SPSS version 15.0 for Windows; the Mann–Whitney test was used for quantitative variables, and Chi-square test for qualitative variables, Fisher exact test for univariate analysis, and binary logistic regression for multivariate analysis. Results were considered statistically significant when p<.05. The sample size needed for the study was calculated at 252 SLN.

ResultsOur study included 125 patients; mean age was 55.6±15 years; 64 (51.2%) were female and 61 (48.8%) male. Some type of comorbidity was present in 55 (44%); the most frequent were: arterial hypertension 35 (28%), diabetes mellitus 6 (4.8%), heart disease 6 (4.8%), lung disease 5 (4%), and 2 (1.6%) active immunosuppression (chronic steroid therapy).

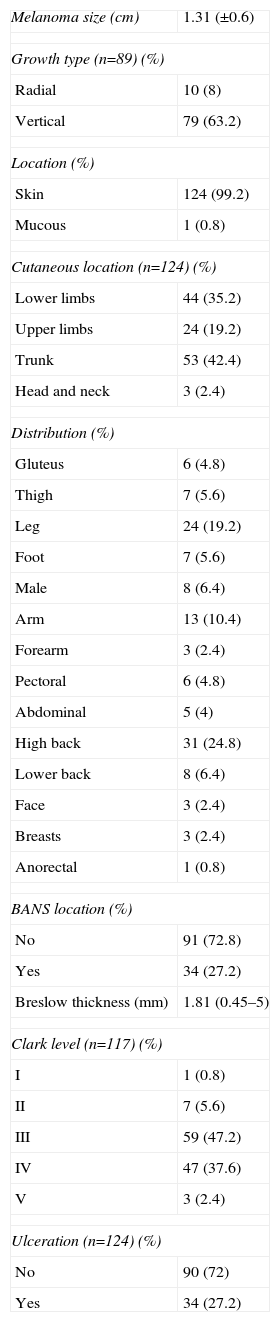

Table 1 lists melanoma characteristics. Tumor stages for our patients were divided as follows: Ia (T1aN0), 19 (15.2%); Ib (T1b-T2aN0) 49 (39.2%); IIa (T2b-T3aN0) 27 (21.6%); IIb (T3b-T4aN0) 17 (13.6%) and IIc (T4bN0) 12 (9.6%). Table 2 shows the study of SLN characteristics.

Melanoma Characteristics.

| Melanoma size (cm) | 1.31 (±0.6) |

| Growth type (n=89) (%) | |

| Radial | 10 (8) |

| Vertical | 79 (63.2) |

| Location (%) | |

| Skin | 124 (99.2) |

| Mucous | 1 (0.8) |

| Cutaneous location (n=124) (%) | |

| Lower limbs | 44 (35.2) |

| Upper limbs | 24 (19.2) |

| Trunk | 53 (42.4) |

| Head and neck | 3 (2.4) |

| Distribution (%) | |

| Gluteus | 6 (4.8) |

| Thigh | 7 (5.6) |

| Leg | 24 (19.2) |

| Foot | 7 (5.6) |

| Male | 8 (6.4) |

| Arm | 13 (10.4) |

| Forearm | 3 (2.4) |

| Pectoral | 6 (4.8) |

| Abdominal | 5 (4) |

| High back | 31 (24.8) |

| Lower back | 8 (6.4) |

| Face | 3 (2.4) |

| Breasts | 3 (2.4) |

| Anorectal | 1 (0.8) |

| BANS location (%) | |

| No | 91 (72.8) |

| Yes | 34 (27.2) |

| Breslow thickness (mm) | 1.81 (0.45–5) |

| Clark level (n=117) (%) | |

| I | 1 (0.8) |

| II | 7 (5.6) |

| III | 59 (47.2) |

| IV | 47 (37.6) |

| V | 3 (2.4) |

| Ulceration (n=124) (%) | |

| No | 90 (72) |

| Yes | 34 (27.2) |

The analytical study was divided into:

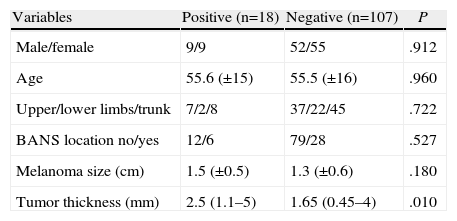

- (a)

SLN positivity predictors (Table 3). Odds ratio for SLN positivity for melanoma Breslow 2–4 mm was 1.797 (0.557–5.798, P=.327) and for Breslow ≥4mm it was 4.643 (1.232–17.498, P=.023).

Table 3.Factors Related to Sentinel Lymph Node Positivity.

Variables Positive (n=18) Negative (n=107) P Male/female 9/9 52/55 .912 Age 55.6 (±15) 55.5 (±16) .960 Upper/lower limbs/trunk 7/2/8 37/22/45 .722 BANS location no/yes 12/6 79/28 .527 Melanoma size (cm) 1.5 (±0.5) 1.3 (±0.6) .180 Tumor thickness (mm) 2.5 (1.1–5) 1.65 (0.45–4) .010 Clark levels: (n=117) n (%) n (%) P I 0 (0) 1 (100) .163 II 0 (0) 7 (100) III 9 (15.3) 50 (84.7) IV 6 (12.8) 41 (87.2) V 2 (66.7) 1 (33.3) Ulceration no/yes (n=124) 12/6 78/28 .543 - (b)

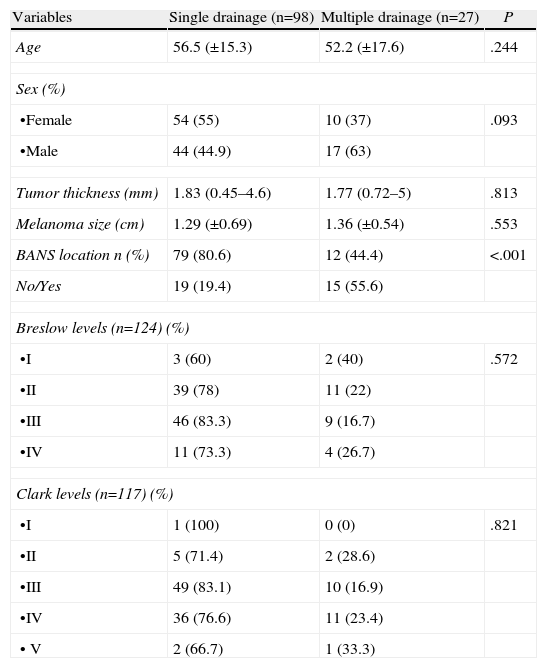

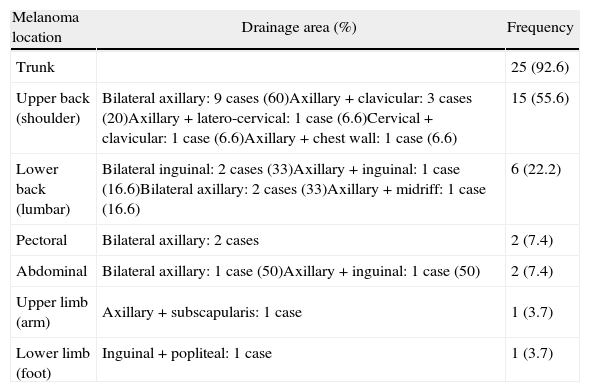

Multiple SLN drainage predictors (Table 4). Table 5: Anatomic distribution of multiple drainage melanoma.

Table 4.Factors Related to Multiple Melanoma Drainage.

Variables Single drainage (n=98) Multiple drainage (n=27) P Age 56.5 (±15.3) 52.2 (±17.6) .244 Sex (%) •Female 54 (55) 10 (37) .093 •Male 44 (44.9) 17 (63) Tumor thickness (mm) 1.83 (0.45–4.6) 1.77 (0.72–5) .813 Melanoma size (cm) 1.29 (±0.69) 1.36 (±0.54) .553 BANS location n (%) 79 (80.6) 12 (44.4) <.001 No/Yes 19 (19.4) 15 (55.6) Breslow levels (n=124) (%) •I 3 (60) 2 (40) .572 •II 39 (78) 11 (22) •III 46 (83.3) 9 (16.7) •IV 11 (73.3) 4 (26.7) Clark levels (n=117) (%) •I 1 (100) 0 (0) .821 •II 5 (71.4) 2 (28.6) •III 49 (83.1) 10 (16.9) •IV 36 (76.6) 11 (23.4) • V 2 (66.7) 1 (33.3) Table 5.Anatomic Distribution of Multiple Drainage Melanoma.

Melanoma location Drainage area (%) Frequency Trunk 25 (92.6) Upper back (shoulder) Bilateral axillary: 9 cases (60)Axillary+clavicular: 3 cases (20)Axillary+latero-cervical: 1 case (6.6)Cervical+clavicular: 1 case (6.6)Axillary+chest wall: 1 case (6.6) 15 (55.6) Lower back (lumbar) Bilateral inguinal: 2 cases (33)Axillary+inguinal: 1 case (16.6)Bilateral axillary: 2 cases (33)Axillary+midriff: 1 case (16.6) 6 (22.2) Pectoral Bilateral axillary: 2 cases 2 (7.4) Abdominal Bilateral axillary: 1 case (50)Axillary+inguinal: 1 case (50) 2 (7.4) Upper limb (arm) Axillary+subscapularis: 1 case 1 (3.7) Lower limb (foot) Inguinal+popliteal: 1 case 1 (3.7)

Treatment of melanoma is surgical. There is general agreement on the primary lesion being excised; however, there is a controversy on what to do with the regional lymph nodes. Therapeutic lymphadenectomy has shown to improve survival in patients with stage III melanoma after ruling out distant metastases.3 Most of the controversy resides in prescribing it for patients with stage I, and II with clinically localized disease; the discussion focuses on intermediate-thickness melanomas, 0.76–4mm, since those <0.76mm have good survival rates at 5 years (96%–99%), while those >4mm have a high risk of developing systemic metastases, reducing the benefit of elective lymphadenectomy.2 Several studies were designed to discern whether prophylactic lymphadenectomy improved prognosis, concluding that only those patients with occult metastases benefited from improved survival. SLNB is a tool to detect metastases.6 Early information of lymph node micro-metastases allows immediate regional lymphadenectomy, influencing patient survival.3

The SLN concept is that each skin area has a specific and sequential lymphatic drainage pathway; therefore, analyzing the first lymph node would rule out metastasis for the rest. The first report on its use for melanoma was published in 1992.6 SLNB is the least aggressive and most effective procedure with 94.4% sensitivity, and a specificity close to 100%.3 In the literature there is variability in SLN positivity (10%–27%), depending on using only HE procedures initially, or IHC procedures, which are part of the current pathological study protocol that require its deferred study.6 In our case series, only 7.1% of patients required lymphadenectomy, as SLNB showed positivity, thus avoiding the morbidity it implies for 92.9% of patients. False negative rates reach 6% in the literature. In our case it was impossible to calculate it due to the retrospective nature of the study, since patients come from different health centers and conduct their postoperative follow-up with them.6 Notably, more than 3 lymph nodes were located in 8.8% of cases, probably related to the high percentage of cases with multiple drainage (21.6%) in our case series.

Introducing preoperative lymphoscintigraphy changed the classical concept of Sappey lymphatic drainage, which states that one lesion can have more than one drainage area and be different from that which was expected.3 Melanomas located on the trunk in different subdivisions show the greatest diversity in drainage, mainly those located in the upper back, head and neck.6–8 In our case series, 21.6% had multiple drainage; patients with trunk melanoma showed high rates of multiple drainage (47.2%); this highlights the importance of preoperative lymphoscintigraphy for correct localization of lymphatic drainage. Only 3 cases with head and neck melanoma were involved: given the complexity of lymphatic drainage in this area, we had more difficulty locating the SLN, as previously described by other authors.7–9

With regard to the disease's prognostic factors, along with Breslow, lymph node involvement is the most important. The only SLN positive outcome predictor factor was tumor thickness. In other studies the same phenomenon is found; therefore, as thickness increases so does the ratio of positive SLN.10–12

In our case series, we found a tendency of SLN positivity increasing as Clark level increases; however, it did not reach significant differences. Although the Clark level has been considered a prognostic factor included in various tumor classification systems, it has been impossible to reproduce results with the same reliability as for tumor thickness.12

We analyzed ulceration as a positivity factor, without finding significant differences, probably due to small sample size. The presence of ulceration implies longer progression time. Many studies show that the latter implies greater aggressiveness with increased risk of metastasis and a worse prognosis.12

Other studies have found links to other factors, such as age, which reached significant differences in the Rosseau [sic: Rousseau] and McMaster studies, with higher ratios of positive cases in patients under 50 years, and for patients under 60 in the van Akkooi studies, as well as the Testori multicenter Italian study in the group between 40 and 60 years.13–16 In our series, we found no significant differences with regards to age for SLN positivity. Probably, this is due in part to our small sample size, although there is no unanimity as to the highest risk age in previous published studies.

SLNB is a very important tool for locating micro-metastases in order to avoid lymphadenectomy-related morbidity. Lymphoscintigraphy is useful for proper localization, because lymphatic drainage pathways are not as predictable. The only factor that in our series was a predictor of positive outcome was tumor thickness.

Conflict of InterestNo conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Soliveres Soliveres E, García Marín A, Díez Miralles M, Nofuentes Riera C, Candela Gomis A, Moragón Gordon M, et al. Biopsia del ganglio centinela en el melanoma. Análisis de nuestra experiencia (125 pacientes). Cir Esp. 2014;92:609–614.