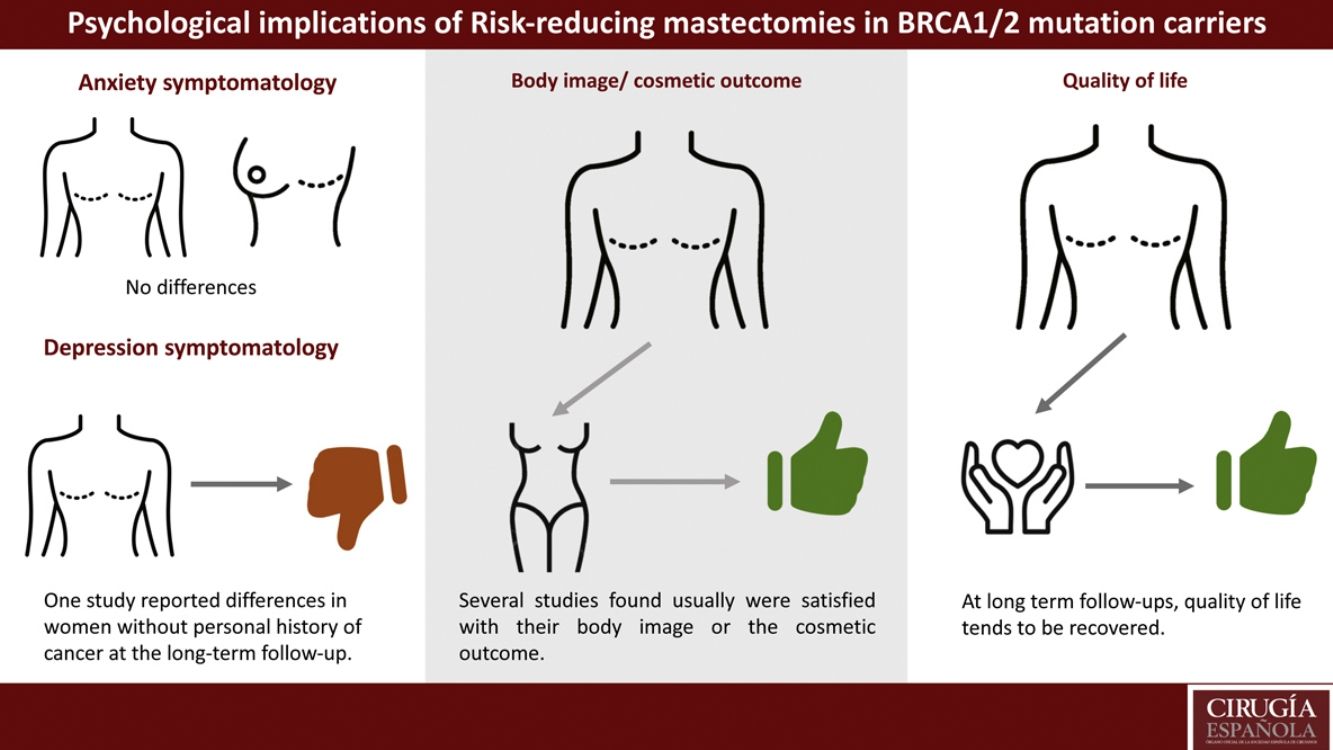

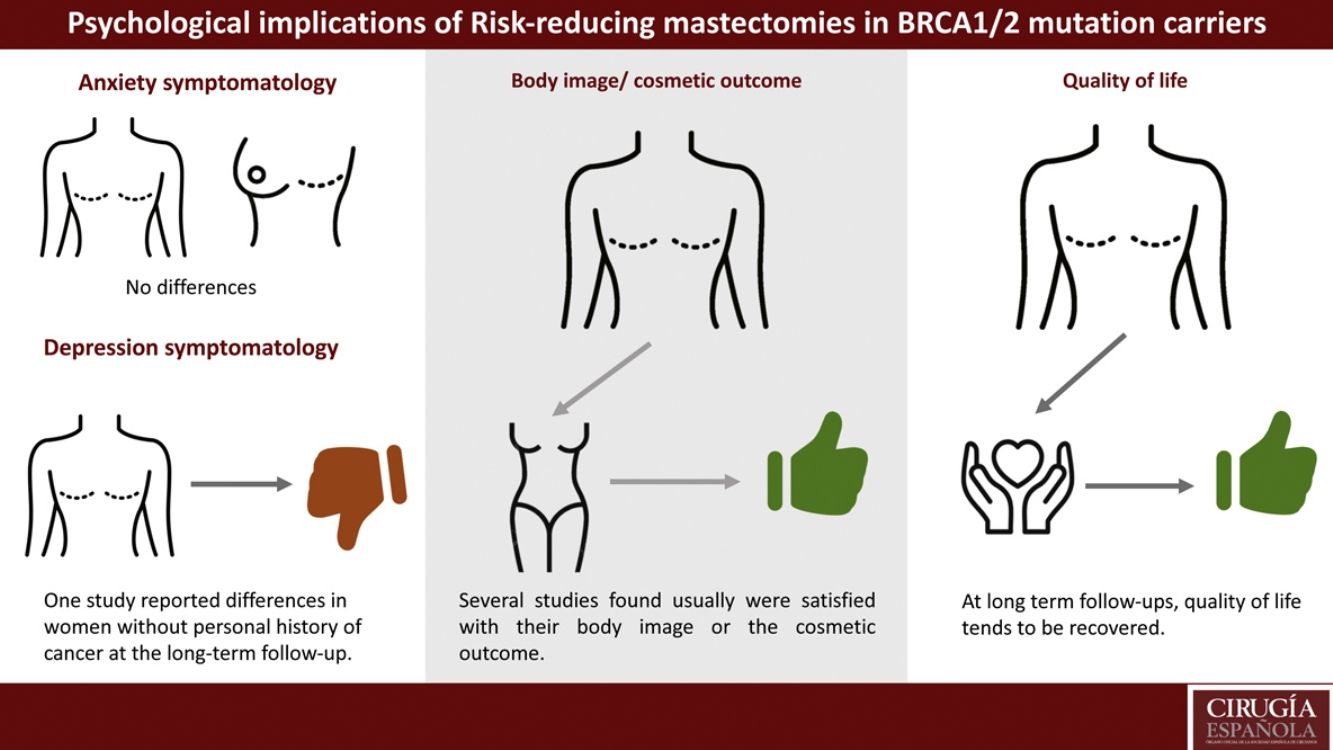

Risk-reducing surgeries decrease the risk of developing breast cancer by 95%. But this type of surgery can be life-changing. This systematic review analyzed anxiety/depressive symptomatology, body image and quality of life on BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with or without a previous oncological history who have undergone risk-reducing mastectomy. PRISMA method was used to conduct this review. The initial search identified 234 studies. However, only 7 achieved the inclusion criteria. No statistically significant differences were found in terms of anxious symptomatology. One study found that depressive symptomatology had increased significantly in women without previous oncological history at the long-term follow-up measure. Women who underwent bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy and implant-based breast reconstruction tended to be satisfied with their body image/cosmetic outcome. No differences were reported at long-term follow-ups, independently of the surgery performed.

Las cirugías reductoras de riesgo descienden un 95% el riesgo de desarrollar cáncer de mama, pero traen consigo repercusiones psicológicas. Esta revisión sistemática tuvo como objetivo analizar la sintomatología ansiosa/depresiva, la imagen corporal y la calidad de vida de mujeres portadoras de una mutación BRCA1/2 con o sin antecedentes oncológicos personales que se habían sometido a una mastectomía reductora de riesgo. Para ello, se utilizó el método PRISMA. La búsqueda inicial identificó 234 estudios. Solo 7 investigaciones cumplieron los criterios de inclusión. No se encontraron diferencias en sintomatología ansiosa. Un estudio concluyó que la sintomatología depresiva aumentó significativamente en mujeres sin antecedentes oncológicos en el seguimiento a largo plazo. Las mujeres que optaron por una mastectomía bilateral reductora de riesgo y fueron reconstruidas mediante prótesis tendían a estar satisfechas con su imagen corporal/resultado cosmético. No se hallaron diferencias a largo plazo en la calidad de vida independientemente de la cirugía realizada.

A familial predisposition exists in 5–10% of all breast cancer cases, of which 15–20% is due to germline mutations in the BRCA1/2 genes1. When BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers were diagnosed under the age 40, the risk of a contralateral breast cancer (CBC) reached nearly 50% in the ensuing 25 years2.

Bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy (BRRM) reduces the risk of developing breast cancer by approximately 90%3. For BRCA1/2 carriers with a previous diagnosis of breast cancer, the overall 10-year survival after contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy (CRRM) was 89%4.

Risk-reducing surgeries decrease the risk of developing cancer, but the surgery itself is may have a significant psychological impact on the women who undergo such procedures5. To restore breast contour, and potentially reduce the negative psychosocial impact of mastectomy, women may opt for breast reconstructive surgery6. There are several types of breast reconstruction: implant-based, autologous, and a combination of both7.

Some risk-reducing surgeries like BRRM with or without reconstruction have long-term consequences that may include significant changes in body image as well as psychosocial, sexual, and physical well-being8. This study aims to perform a systematic review to analyze anxiety/depressive symptomatology, body image and quality of life on BRCA1/2 carriers with or without a previous oncological history who have undergone risk-reducing mastectomies.

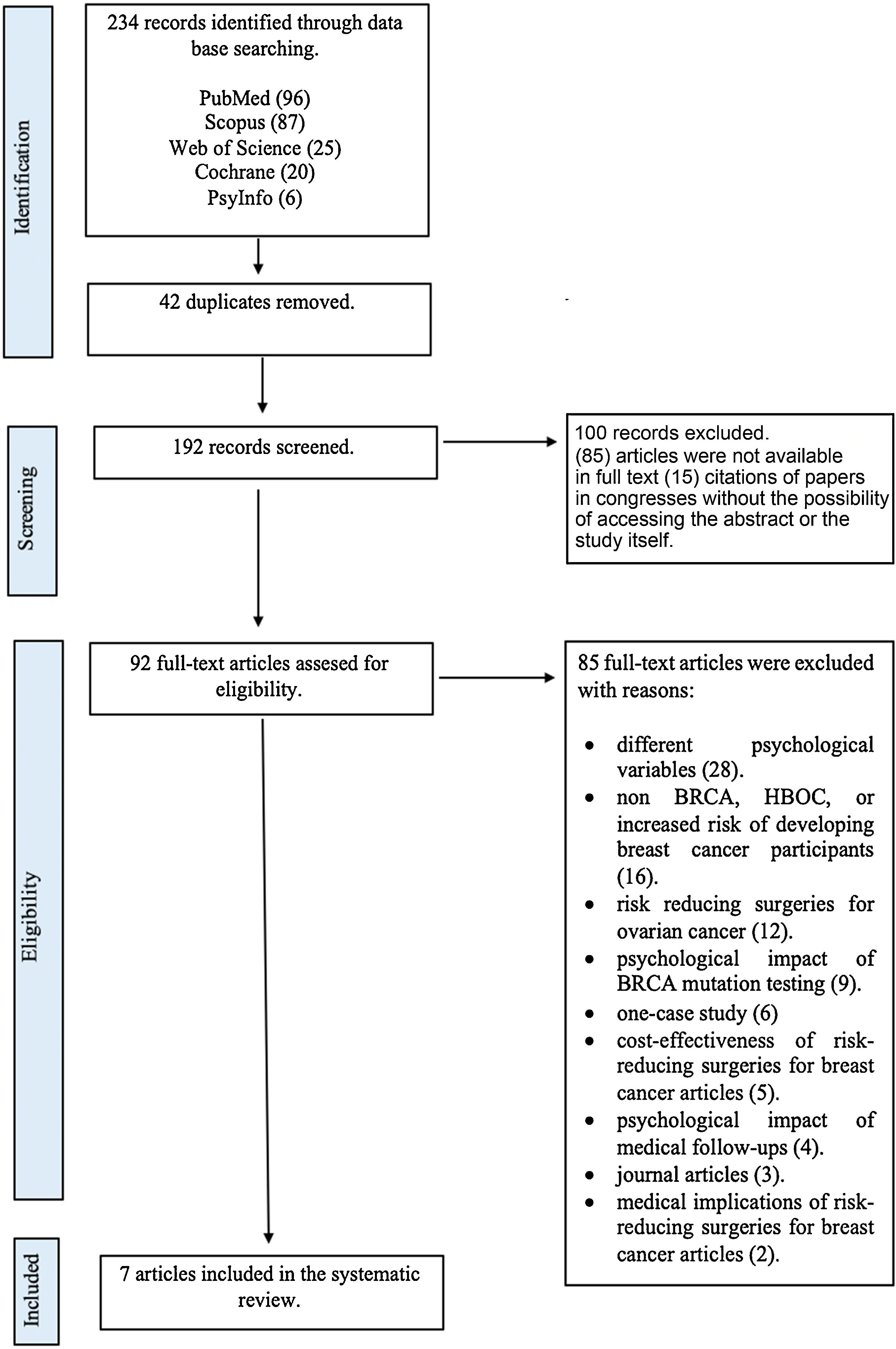

MethodsThis systematic review was designed following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines9 (see Fig. 1) and is registered with PROSPERO (CRD 42020172753).

Search strategyA literature search using Pubmed, Cochrane, Web of Science, Scopus y PsycInfo was conducted. Years chosen to reach were January, 2000-October, 2020. The language used was English. Three categories of terms were searched in all the data bases: (1) risk-reducing surgery, (2) BRCA mutation carriers (3) psychological variables. In Pubmed and Cochrane the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used: (1) risk-reducing surgery (RRS), prophylactic surgery, prophylactic mastectomy, contralateral mastectomy, bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy, risk-reducing mastectomy, reparative surgery, breast reconstruction, autologous breast reconstruction and implant-based breast reconstruction. (2) BRCA, BRCA1/2, HBOC, Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome, BRCA1/2 mutation, BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, BRCA mutation carriers, BRCA1/2 carriers, breast cancer and CMOH. (3) Psychology, health psychology, psycho-oncology, quality of life, cosmetic outcomes, body image, anxiety and depression. These Mesh terms were used as keywords in PsycInfo and Web of Science. The Boolean character used to link the three categories of search terms was ‘AND’. MeSH terms or keywords had to be included in the title or abstract of the paper. Also, grey literature was reviewed, using EThOS as a resource.

Criteria for considering studies for this reviewType of participantsThe sample used in the studies selected were BRCA mutation carriers with or without previous personal history of breast cancer, or women with familiar history of breast cancer. Also, these women had undergone a risk-reducing mastectomy (RRM) (BRRM, CRRM) with or without breast reconstruction. Patients that had undergone to other type of risk-reducing surgery (bilateral risk reducing surgery salpingo-oophorectomy (BRRSO)) could be taken in consideration as long as a risk-reducing mastectomy (BRRM, CRRM) with or without breast reconstruction have been performed.

Psychological variablesThe psychological variables selected were anxiety or anxiety symptomatology, depression or depression symptomatology, body image or satisfaction with outcome and quality of life. The type of measures included were psychometric instruments (quantitative measure) and self-report measures (qualitative).

Comparison between participantsIn case of group comparison, the intervention group had to be BRCA1/2 mutation carriers /women with familiar history of breast cancer who underwent any type of risk reducing mastectomy with or without previous oncological history.

Study designExperimental and descriptive studies were included as long as they met the established methodological criteria. Cross-sectional and longitudinal or prospective studies were also included.

Exclusion criteriaStudies that only addressed biological and somatic parameters (e.g. DNA sequencing, surgical options), consequences of medical treatment, recommendations for early detection of breast cancer and prevalence of mutations in patients with this pathology were not included. Journal articles were excluded. Studies whose sample were women without BRCA1/2 mutation exclusively or BRCA1/2 carriers that were considering risk-reducing surgeries but have not undergone any were also left out. Likewise, studies that exclusively referred to risk-reducing surgeries for ovarian cancer in women with BRCA1/2 were discarded.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studiesDefinitions of risk of bias were based in those proposed by Carbine et al.10. Selection bias was defined as systematic differences in the selection of the sample. Performance bias was defined as systematic differences in in the measurement moments. Attrition bias was defined as systematic differences in withdrawals or exclusions of participants from the results of a study.

- 1

Selection bias: sample which participated in prior studies11.

- 2

Performance bias: absence of psychological measurement prior RRS12.

- 3

Attrition of bias: high dropouts’ rate (>30%)12,13,14, non-participation at long term follow ups14–16, lack of reasons/possible explanations of the non-participation or withdrawal12,13,15 and absence of dropouts’ rate 17.

The initial search resulted in 234 publications. Removal of duplicates resulted in 192 articles. On screening, 100 studies failed to meet the inclusion criteria and were removed. The remaining 92 articles were read in full text and at this stage, 82 articles were excluded. The reasons for exclusion were: 28 studies evaluated different psychological variables, 16 did not meet the participants criteria, 12 articles studied risk-reducing surgeries for ovarian cancer, 9 measured the psychological impact of BRCA mutation testing, 6 were one-case study, 5 explored cost-effectiveness of risk-reducing surgeries for breast cancer, 4 analyzed the psychological impact of medical follow-ups, 3 were journal articles and 2 studied the medical implication of risk-reducing surgeries for breast cancer. Finally, only 7 studies were included in this systematic review (see Table 1).

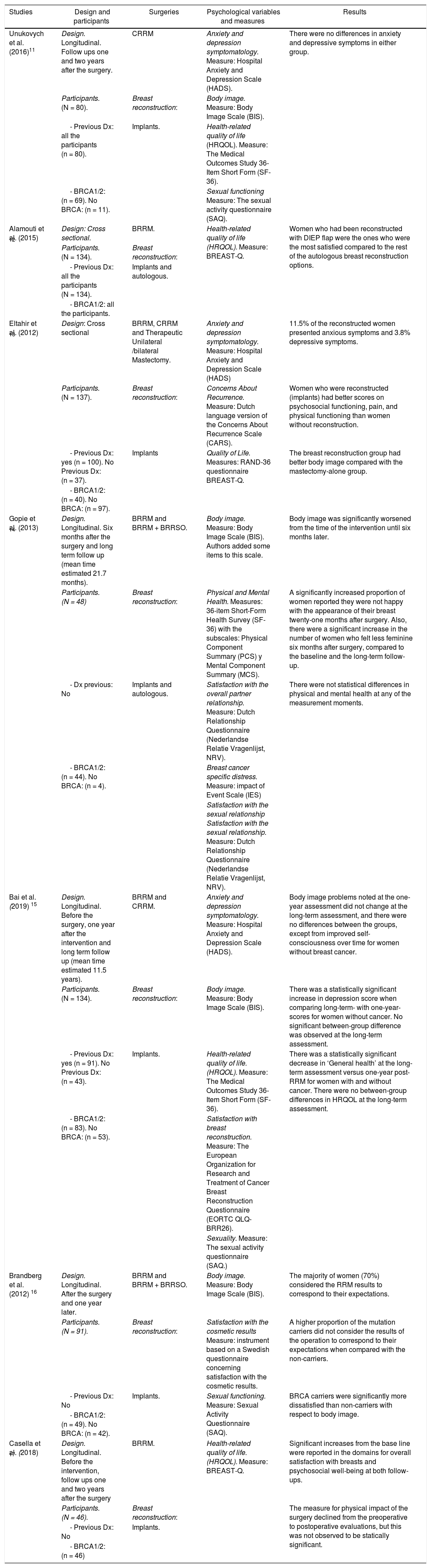

Description and results of the included studies.

| Studies | Design and participants | Surgeries | Psychological variables and measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unukovych et al. (2016)11 | Design. Longitudinal. Follow ups one and two years after the surgery. | CRRM | Anxiety and depression symptomatology. Measure: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). | There were no differences in anxiety and depressive symptoms in either group. |

| Participants. (N = 80). | Breast reconstruction: | Body image. Measure: Body Image Scale (BIS). | ||

| - Previous Dx: all the participants (n = 80). | Implants. | Health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Measure: The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form (SF-36). | ||

| - BRCA1/2: (n = 69). No BRCA: (n = 11). | Sexual functioning Measure: The sexual activity questionnaire (SAQ). | |||

| Alamouti et al. (2015) 12 | Design: Cross sectional. | BRRM. | Health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Measure: BREAST-Q. | Women who had been reconstructed with DIEP flap were the ones who were the most satisfied compared to the rest of the autologous breast reconstruction options. |

| Participants. (N = 134). | Breast reconstruction: | |||

| - Previous Dx: all the participants (N = 134). | Implants and autologous. | |||

| - BRCA1/2: all the participants. | ||||

| Eltahir et al. (2012) 13 | Design: Cross sectional | BRRM, CRRM and Therapeutic Unilateral /bilateral Mastectomy. | Anxiety and depression symptomatology. Measure: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | 11.5% of the reconstructed women presented anxious symptoms and 3.8% depressive symptoms. |

| Participants. (N = 137). | Breast reconstruction: | Concerns About Recurrence. Measure: Dutch language version of the Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS). | Women who were reconstructed (implants) had better scores on psychosocial functioning, pain, and physical functioning than women without reconstruction. | |

| - Previous Dx: yes (n = 100). No Previous Dx: (n = 37). | Implants | Quality of Life. Measures: RAND-36 questionnaire BREAST-Q. | The breast reconstruction group had better body image compared with the mastectomy-alone group. | |

| - BRCA1/2: (n = 40). No BRCA: (n = 97). | ||||

| Gopie et al. (2013) 14 | Design. Longitudinal. Six months after the surgery and long term follow up (mean time estimated 21.7 months). | BRRM and BRRM + BRRSO. | Body image. Measure: Body Image Scale (BIS). Authors added some items to this scale. | Body image was significantly worsened from the time of the intervention until six months later. |

| Participants. (N = 48) | Breast reconstruction: | Physical and Mental Health. Measures: 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) with the subscales: Physical Component Summary (PCS) y Mental Component Summary (MCS). | A significantly increased proportion of women reported they were not happy with the appearance of their breast twenty-one months after surgery. Also, there were a significant increase in the number of women who felt less feminine six months after surgery, compared to the baseline and the long-term follow-up. | |

| - Dx previous: No | Implants and autologous. | Satisfaction with the overall partner relationship. Measure: Dutch Relationship Questionnaire (Nederlandse Relatie Vragenlijst, NRV). | There were not statistical differences in physical and mental health at any of the measurement moments. | |

| - BRCA1/2: (n = 44). No BRCA: (n = 4). | Breast cancer specific distress. Measure: impact of Event Scale (IES) | |||

| Satisfaction with the sexual relationship Satisfaction with the sexual relationship. Measure: Dutch Relationship Questionnaire (Nederlandse Relatie Vragenlijst, NRV). | ||||

| Bai et al. (2019) 15 | Design. Longitudinal. Before the surgery, one year after the intervention and long term follow up (mean time estimated 11.5 years). | BRRM and CRRM. | Anxiety and depression symptomatology. Measure: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). | Body image problems noted at the one-year assessment did not change at the long-term assessment, and there were no differences between the groups, except from improved self-consciousness over time for women without breast cancer. |

| Participants. (N = 134). | Breast reconstruction: | Body image. Measure: Body Image Scale (BIS). | There was a statistically significant increase in depression score when comparing long-term- with one-year-scores for women without cancer. No significant between-group difference was observed at the long-term assessment. | |

| - Previous Dx: yes (n = 91). No Previous Dx: (n = 43). | Implants. | Health-related quality of life. (HRQOL). Measure: The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form (SF-36). | There was a statistically significant decrease in ‘General health’ at the long-term assessment versus one-year post-RRM for women with and without cancer. There were no between-group differences in HRQOL at the long-term assessment. | |

| - BRCA1/2: (n = 83). No BRCA: (n = 53). | Satisfaction with breast reconstruction. Measure: The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Reconstruction Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-BRR26). | |||

| Sexuality. Measure: The sexual activity questionnaire (SAQ.) | ||||

| Brandberg et al. (2012) 16 | Design. Longitudinal. After the surgery and one year later. | BRRM and BRRM + BRRSO. | Body image. Measure: Body Image Scale (BIS). | The majority of women (70%) considered the RRM results to correspond to their expectations. |

| Participants. (N = 91). | Breast reconstruction: | Satisfaction with the cosmetic results Measure: instrument based on a Swedish questionnaire concerning satisfaction with the cosmetic results. | A higher proportion of the mutation carriers did not consider the results of the operation to correspond to their expectations when compared with the non-carriers. | |

| - Previous Dx: No | Implants. | Sexual functioning. Measure: Sexual Activity Questionnaire (SAQ). | BRCA carriers were significantly more dissatisfied than non-carriers with respect to body image. | |

| - BRCA1/2: (n = 49). No BRCA: (n = 42). | ||||

| Casella et al. (2018) 17 | Design. Longitudinal. Before the intervention, follow ups one and two years after the surgery | BRRM. | Health-related quality of life. (HRQOL). Measure: BREAST-Q. | Significant increases from the base line were reported in the domains for overall satisfaction with breasts and psychosocial well-being at both follow-ups. |

| Participants. (N = 46). | Breast reconstruction: | The measure for physical impact of the surgery declined from the preoperative to postoperative evaluations, but this was not observed to be statically significant. | ||

| - Previous Dx: No | Implants. | |||

| - BRCA1/2: (n = 46) |

Note: Dx: diagnosis. BRRM: bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy. CRRM: contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy. BRRSO: bilateral risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. RRM: risk-reducing mastectomy.

In terms of RRS, six out of seven studies performed BRRM12−17. Three studied CRRM11,13,15. Other studies investigated risk reducing mastectomies (RRM)+ risk reducing surgeries: MBRR + BRRSO14,16. One revision analyzed unilateral therapeutic and unilateral risk-reducing mastectomy13.

With regard to breast reconstruction. Five studies analyzed implant-based reconstruction been this type of breast reconstruction technique the main performed11,13,15–17. Two articles performed different types of breast reconstruction, implant based and autologous reconstruction12,14. In four studies, some of/all the participants had previous oncological history11,12,13,15.

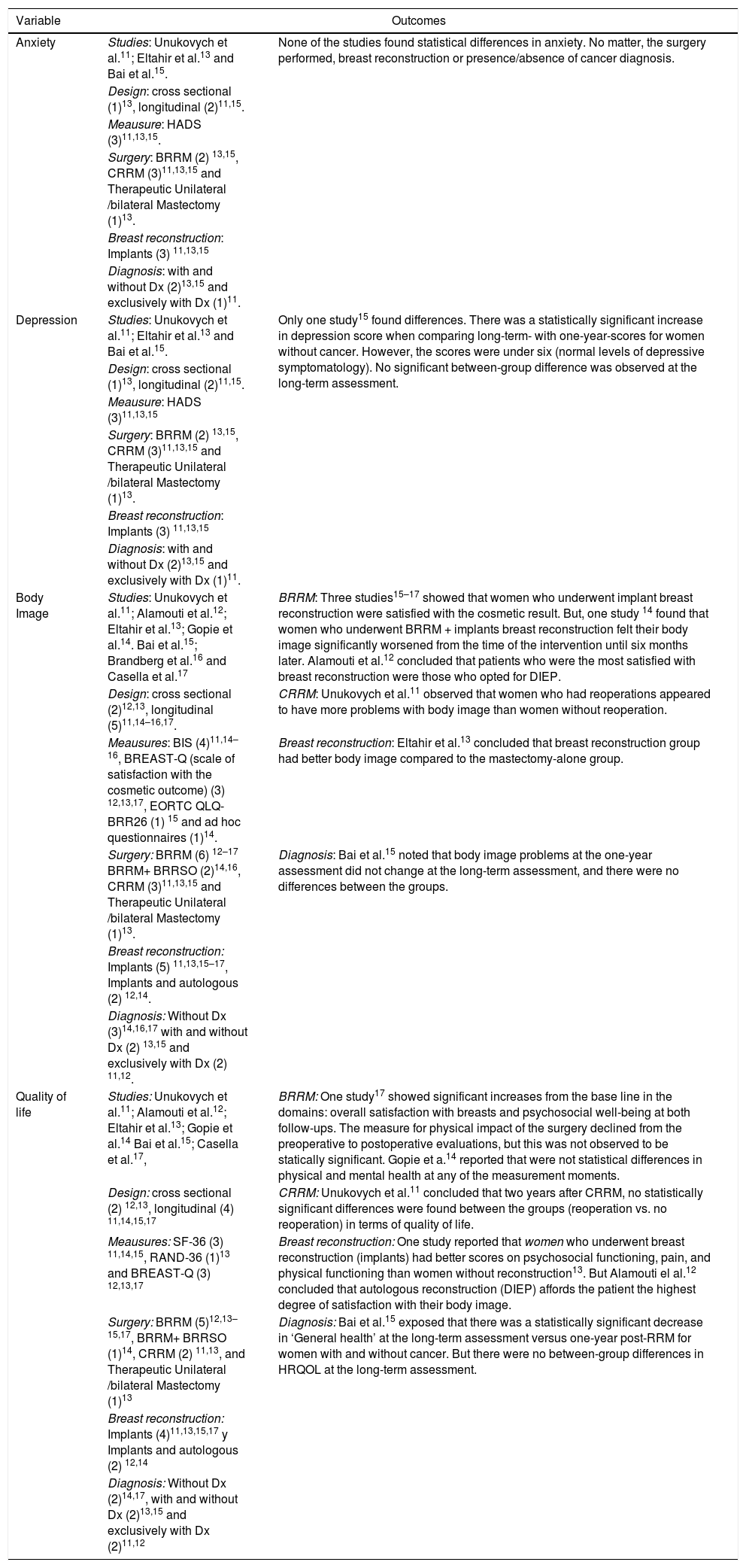

Relating to psychological variables (see Table 2) three articles studied anxiety symptomatology/anxiety11,13,15 three analyzed depressive symptomatology/depression11,13,15, all the studies took in to account body image/ satisfaction with outcome11–18 and six studies examined quality of life11,12,13–15,17.

Outcomes of the psychological variables.

| Variable | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Studies: Unukovych et al.11; Eltahir et al.13 and Bai et al.15. | None of the studies found statistical differences in anxiety. No matter, the surgery performed, breast reconstruction or presence/absence of cancer diagnosis. |

| Design: cross sectional (1)13, longitudinal (2)11,15. | ||

| Meausure: HADS (3)11,13,15. | ||

| Surgery: BRRM (2) 13,15, CRRM (3)11,13,15 and Therapeutic Unilateral /bilateral Mastectomy (1)13. | ||

| Breast reconstruction: Implants (3) 11,13,15 | ||

| Diagnosis: with and without Dx (2)13,15 and exclusively with Dx (1)11. | ||

| Depression | Studies: Unukovych et al.11; Eltahir et al.13 and Bai et al.15. | Only one study15 found differences. There was a statistically significant increase in depression score when comparing long-term- with one-year-scores for women without cancer. However, the scores were under six (normal levels of depressive symptomatology). No significant between-group difference was observed at the long-term assessment. |

| Design: cross sectional (1)13, longitudinal (2)11,15. | ||

| Meausure: HADS (3)11,13,15 | ||

| Surgery: BRRM (2) 13,15, CRRM (3)11,13,15 and Therapeutic Unilateral /bilateral Mastectomy (1)13. | ||

| Breast reconstruction: Implants (3) 11,13,15 | ||

| Diagnosis: with and without Dx (2)13,15 and exclusively with Dx (1)11. | ||

| Body Image | Studies: Unukovych et al.11; Alamouti et al.12; Eltahir et al.13; Gopie et al.14. Bai et al.15; Brandberg et al.16 and Casella et al.17 | BRRM: Three studies15–17 showed that women who underwent implant breast reconstruction were satisfied with the cosmetic result. But, one study 14 found that women who underwent BRRM + implants breast reconstruction felt their body image significantly worsened from the time of the intervention until six months later. Alamouti et al.12 concluded that patients who were the most satisfied with breast reconstruction were those who opted for DIEP. |

| Design: cross sectional (2)12,13, longitudinal (5)11,14–16,17. | CRRM: Unukovych et al.11 observed that women who had reoperations appeared to have more problems with body image than women without reoperation. | |

| Meausures: BIS (4)11,14–16, BREAST-Q (scale of satisfaction with the cosmetic outcome) (3) 12,13,17, EORTC QLQ-BRR26 (1) 15 and ad hoc questionnaires (1)14. | Breast reconstruction: Eltahir et al.13 concluded that breast reconstruction group had better body image compared to the mastectomy-alone group. | |

| Surgery: BRRM (6) 12–17 BRRM+ BRRSO (2)14,16, CRRM (3)11,13,15 and Therapeutic Unilateral /bilateral Mastectomy (1)13. | Diagnosis: Bai et al.15 noted that body image problems at the one-year assessment did not change at the long-term assessment, and there were no differences between the groups. | |

| Breast reconstruction: Implants (5) 11,13,15–17, Implants and autologous (2) 12,14. | ||

| Diagnosis: Without Dx (3)14,16,17 with and without Dx (2) 13,15 and exclusively with Dx (2) 11,12. | ||

| Quality of life | Studies: Unukovych et al.11; Alamouti et al.12; Eltahir et al.13; Gopie et al.14 Bai et al.15; Casella et al.17, | BRRM: One study17 showed significant increases from the base line in the domains: overall satisfaction with breasts and psychosocial well-being at both follow-ups. The measure for physical impact of the surgery declined from the preoperative to postoperative evaluations, but this was not observed to be statically significant. Gopie et a.14 reported that were not statistical differences in physical and mental health at any of the measurement moments. |

| Design: cross sectional (2) 12,13, longitudinal (4) 11,14,15,17 | CRRM: Unukovych et al.11 concluded that two years after CRRM, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups (reoperation vs. no reoperation) in terms of quality of life. | |

| Meausures: SF-36 (3) 11,14,15, RAND-36 (1)13 and BREAST-Q (3) 12,13,17 | Breast reconstruction: One study reported that women who underwent breast reconstruction (implants) had better scores on psychosocial functioning, pain, and physical functioning than women without reconstruction13. But Alamouti el al.12 concluded that autologous reconstruction (DIEP) affords the patient the highest degree of satisfaction with their body image. | |

| Surgery: BRRM (5)12,13–15,17, BRRM+ BRRSO (1)14, CRRM (2) 11,13, and Therapeutic Unilateral /bilateral Mastectomy (1)13 | Diagnosis: Bai et al.15 exposed that there was a statistically significant decrease in ‘General health’ at the long-term assessment versus one-year post-RRM for women with and without cancer. But there were no between-group differences in HRQOL at the long-term assessment. | |

| Breast reconstruction: Implants (4)11,13,15,17 y Implants and autologous (2) 12,14 | ||

| Diagnosis: Without Dx (2)14,17, with and without Dx (2)13,15 and exclusively with Dx (2)11,12 | ||

Note: Dx: diagnosis. BRRM: bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy. CRRM: contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy. BRRSO: bilateral risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy.

Elthair et al.13 studied bilateral/unilateral mastectomy, either risk-reducing or therapeutic with and without reconstruction (implants). The results of this investigation showed that 11.5% of women who had opted for a risk-reducing mastectomy (either bilateral or unilateral mastectomy) with breast reconstruction (n = 26) and 12.1% of women who underwent therapeutic mastectomy with breast reconstruction (n = 66) presented anxiety symptomatology. Two women underwent risk-reducing mastectomy without reconstruction but did not answer the anxiety protocol. About therapeutic mastectomy without breast reconstruction 14% of these women (n = 43) presented this symptomatology. Also, Bai et al.15 analyzed BRRM and CRRM these researchers found that women with and without previous oncological history had higher scores at long term-assessments (11.5 mean years after the surgery) compared to one-year assessment. But these outcomes were not statically significant.

Unykovych et al.11 investigated CRRM, these researchers compared women with reoperations and without them. All the sample personal had breast cancer antecedents. There were no statistically significant differences found in anxiety between both groups.

Depressive symptomatology/depressionAs to BRRM, Eltahir et al.13 in their research found that 3.8% of women who opted for bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy and breast reconstruction presented depressive symptoms. Similar scores were observed in the reconstruction following therapeutic mastectomy group (4.5%). Two women underwent risk-reducing mastectomy without reconstruction but did not answer the depression protocol. About therapeutic mastectomy without breast reconstruction 3% of these women (n = 43) presented depression symptomatology.

As far as CRRM is concerned, there were not differences in depression symptomatology between the reoperation and no reoperation groups in women with personal history of breast cancer11. Also, Bai et al.15 analyzed BRRM and CRRM these researchers found that women with and without previous oncological history had higher scores at long-term assessments (11.5 mean years after the surgery) compared to one-year assessment. There was a statistically significant increase in depression score when comparing long term with one-year scores for women without cancer (BRRM performed) (p = 0.042).

Body image/satisfaction with the outcomeConcerning BRRM, the majority of women (70%) considered that the RRM results to correspond to their expectations.16. However, a higher proportion of the mutation carriers did not consider the results of the operation to correspond to their expectations when compared with the non-carriers (p = 0.037). Gopie et al.14 reported that women who opted for BRRM with reconstruction perceived their body image significantly (p < 0.001) worsened six months after the surgery compared to the preoperative scores. Twenty-one months after the surgery body image tended to decrease without significance (p = 0.06). 54.3% of sample (N = 35) were dissatisfied with the appearance of their breasts six months after the intervention (p = 0.001). This percentage decreased 21 months after the surgery to 28.6%. However, it was still significant (p = 0.02).

Regarding to CRRM, Unuvoych et al.11 observed a statistically significant difference (81% versus 48%, p = 0.01) between the reoperation group versus no reoperation in the item “dissatisfaction with the body” of BIS. Women who had reoperations appeared to have more problems with body image than women without reoperation.

Analyzing BRRM and CRRM Bai et al.15 concluded that approximately 70% of the women with breast cancer (n = 44) and 45–50% of the women without cancer reported sexual/physical attractiveness problems at the long-term follow-up. In addition, large proportions of women in both groups were dissatisfied with their scars at the long-term assessment, 62% of the cancer group and 49% of the group without cancer. Other body image problems, such as feeling less feminine after the surgery, difficulties with seeing oneself naked, or body feeling less whole, were also relatively persistent.

As far as reparative surgeries are concerned, Elthair et al.13 reported that women with breast reconstruction were more satisfied with their appearance than women with only a mastectomy. Casella et al.17 suggested that women who opted for an implant-based breast reconstruction were satisfied with the outcome. Alamouti et al.12 compared autologous breast reconstructive options and the deep inferior epigastric artery flap (DIEP) was the most popular choice (N = 40) resulting in the highest satisfaction rate among patients, 60%.

Quality of lifeAs to BRRM, Bai et al.15 described a statistically significant decrease in ‘General health’ at the long-term assessment versus one-year post-RRM for both groups (p = .042). But there were no between-group differences in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) at the long-term assessment. In line with the above, Gopie et al.14 that general physical health, at baseline significantly declined at the first follow up (p = 0.001). However, general mental health at baseline was significantly improved after six months (p = 0.02). For both general mental and physical health, the course did not significantly change from the base line to twenty-one months after the surgery.

Regarding to contralateral/bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy with breast reconstruction, Casella et al.17 found significant increases from the base line in domains like overall satisfaction with breasts (p < 005) and psychosocial well-being (p < 0.05) at both follow-ups (1 and 2 years). Nevertheless, Unukovych et al.11 reported that there were not significant differences two years after CRRM between both groups (reoperation vs. no reoperation).

With regard to breast reconstruction, Elthair et al.13 concluded women that underwent mastectomy and successful breast reconstruction (implants) fared better psychosocially (p = 0.008) than women with mastectomy alone. Furthermore, they functioned better physically (p = 0.012), experiencing less pain and fewer limitations (p = 0.007). Alamouti el al.12 concluded that breast reconstruction helps to maintain their quality of life through significant reduction in risk of developing breast cancer. Being DIEP flap the most popular choice (N = 40) and resulting in the highest satisfaction rate among patients, 60%.

DiscussionOther findings which support the results of this review in terms of anxiety are those described by Metcalfe et al.18. These researchers did not find statistically significant differences between women who had undergone mastectomy with immediate or delayed reconstruction and those who did not opt for breast reconstruction one year after the intervention. The lack of statically significant differences in the studies included in this review could be explained by the fact that perhaps it is the situation of undergoing a surgical intervention which would induce this type of symptomatology and not a specific risk-reducing surgery. Furthermore, the absence of differences has been maintained in the two longitudinal studies.

Only one study that analyzed depressive symptomatology/depression found statistically significant differences15. Together, these studies suggest that CRRM and personal oncological history were not related to depressive symptomatology in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. However, women without cancer who underwent BRRM had a statistically significant increase in depression at the long-term assessment. None of the three studies that measure depression/depressive symptomatology found clinical depressive symptomatology or depression regardless of their design or the RRS performed. Isern et al.19 found that 98% of women who opted for risk reducing mastectomy did not present clinical depressive symptomatology. One possible explanation of these review findings could be that depressive symptomatology/depression may be linked to breast reconstruction surgeries. One investigation conducted by Al-Ghazal et al.20 reported that depressive symptomatology/depression was noticeably less in women with immediate reconstruction compared to those with delayed reconstruction (transverse rectus abdominus muscle (TRAM) flap and latissimus dorsi flap.

As far as BRRM is concerned, three studies15–17 showed that women who underwent implant breast reconstruction were satisfied with the cosmetic result. In accordance with these results, a systematic review21 that analyzed the aesthetic satisfaction in women who had underwent RRM + breast reconstruction reported on number of women satisfied with the look of the breasts, which ranged from 77% to 90%. One study suggested that BRRM + implant-based breast reconstruction had a negative impact on body image14. Often, diminished cosmetic satisfaction was associated with surgical complications or reconstruction, or both10.

According to the findings of Unuvoych et al.11, one study22 with mean follow-up of 6.6 years showed that 64% of 223 women underwent at least 1 unanticipated reoperation due to BRRM. Also, 94 women reconstructed with implants, underwent at least 1 procedure due to the implant pocket/s. Nonetheless, one systematic review reported that women who had undergone BRRM were satisfied with their body image and this perception did not change significantly over time24. Frost et al.23 reported that, 45% of women that underwent CRRM + breast reconstruction had one or more reintervention, and this fact was associated with lower satisfaction in these group. Another study found a significantly lower satisfaction with breasts in women who underwent implant-based reconstruction compared to those who opted for autologous reconstruction25. Regarding to breast reconstruction, one hypothesis that may explain these results is that implant-based breast reconstruction has a longer research trajectory than autologous breast reconstruction following RRS. That may be the reason why there are more studies with this type of breast reconstruction available. Gopie et al.14 suggested that the breast reconstruction process may last up to 1.5 years, including expansion of tissue expanders, replacement with definite implants, additional aesthetic corrections and nipple reconstruction. This fact may explain the dissatisfaction with the body image/with the outcome in studies with shorter follow-ups.

As to quality of life, and BRRM, one study17 showed significant increases from the base line in the domains: overall satisfaction with breasts and psychosocial well-being at both follow-ups. Altman et al. conducted a systematic review analyzing several RRS and concluded that After RRM, most patients report satisfaction with their decision and outcomes with no significant negative impact on HRQOL. However, Bai et al.15 exposed that there was a statistically significant decrease in ‘General health’ at the long-term assessment versus one-year post-RRM for women with and without cancer. These results could be explained by breast reconstruction process like was mentioned before14. But, there were no between-group differences in HRQOL at the long-term assessment, that may be due to the fact that the breast reconstruction may be finally completed at the long-term assessment. According to what was said before, Gopie et al.14 reported that were not statistical differences in physical and mental health at any of the measurement moments. With regard to CRRM, Unukovych et al.11 concluded that two years after CRRM, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups (reoperation vs. no reoperation). One possible explanation of RSS benefits in terms of quality of life may be due to the relief from the reduction of the cancer risk (anxiety).

In terms of quality of life and breast reconstruction the results were divergent. One study reported that women who underwent breast reconstruction (implants) had better scores on psychosocial functioning, pain, and physical functioning than women without reconstruction13. But Alamouti el al.12 concluded that autologous reconstruction (DIEP) affords the patient the highest degree of satisfaction with their body image. According to these results, Carbine et al.10 concluded that women generally reported satisfaction with their decision to have risk-reducing mastectomy (RRM), but were less consistently favorable regarding the cosmetic outcome.

One of the significant limitations of this review includes the fact BRCA1/2 patients have an increased risk to develop breast and ovarian cancer so many studies opted to perform risk-reducing surgeries to decrease both diseases. Due to this reason, there are few studies that only focus on decrease breast cancer in BRCA1/2 carriers. Also, the results of the breast reconstruction studies should be taken cautiously because in 20 years, new techniques such as autologous breast reconstruction have been developed and the long-term psychological repercussions of this surgery remain to be seen. Additionally, the number of studies that analyzed BRRM was higher than CRRM that may magnify the implications of BRRM. Another limitation was the variety of assessment instruments making complex the comparison between the investigations that study the same variable. This fact occurred especially with quality of life.

This review tried to show the psychological implications of risk-reducing surgeries for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Women who undergo risk-reducing mastectomies do it to prevent breast cancer and not to cure it. This fact should be remaining because these surgeries may be perceived for these women as unnecessary worsening of body image and quality of life. For this reason, as has been stated throughout the review, it is notably important to continue investigating in this field especially about breast reconstruction surgeries to clarify which interventions could help preserve body image and life quality, as well as minimize anxiety and depression symptomatology.

The results of this systematic review show that there were not statistical differences in anxiety/anxiety symptomatology regardless of the RRM performed, type of reconstruction or personal history of cancer. Regarding to depression/depressive symptomatology one study reported differences when comparing long-term- with one-year-scores for women without cancer. Several studies found that women who underwent BRRM + implant-based breast reconstruction tended to be satisfied with their body image or the cosmetic outcome. One study reported a significant increase from the base line to both follow-ups in quality of live after BBRM. But, in general, no differences were reported at long-term follow-ups, independently of the RRM performed.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestAll the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Luque Suárez S, Olivares Crespo ME, Brenes Sánchez JM, Herrera de la Muela M. Aspectos psicológicos en las mastectomías reductoras de riesgo en mujeres portadoras de mutación patogénica BRCA1/2. Cir Esp. 2022;100:7–17.