Surgical site infection (SSI) is the main cause of nosocomial infection in Spain. The aim of this study was to analyze the incidence of SSI and to evaluate its risk factors in patients undergoing rectal surgery.

MethodsProspective cohort study, conducted from January 2013 to December 2016. Patient, surgical intervention and infection variables were collected. Infection rate was calculated after a maximum period of 30 days of incubation. The effect of different risk factors on infection was assessed using the odds ratio adjusted by a logistic regression model.

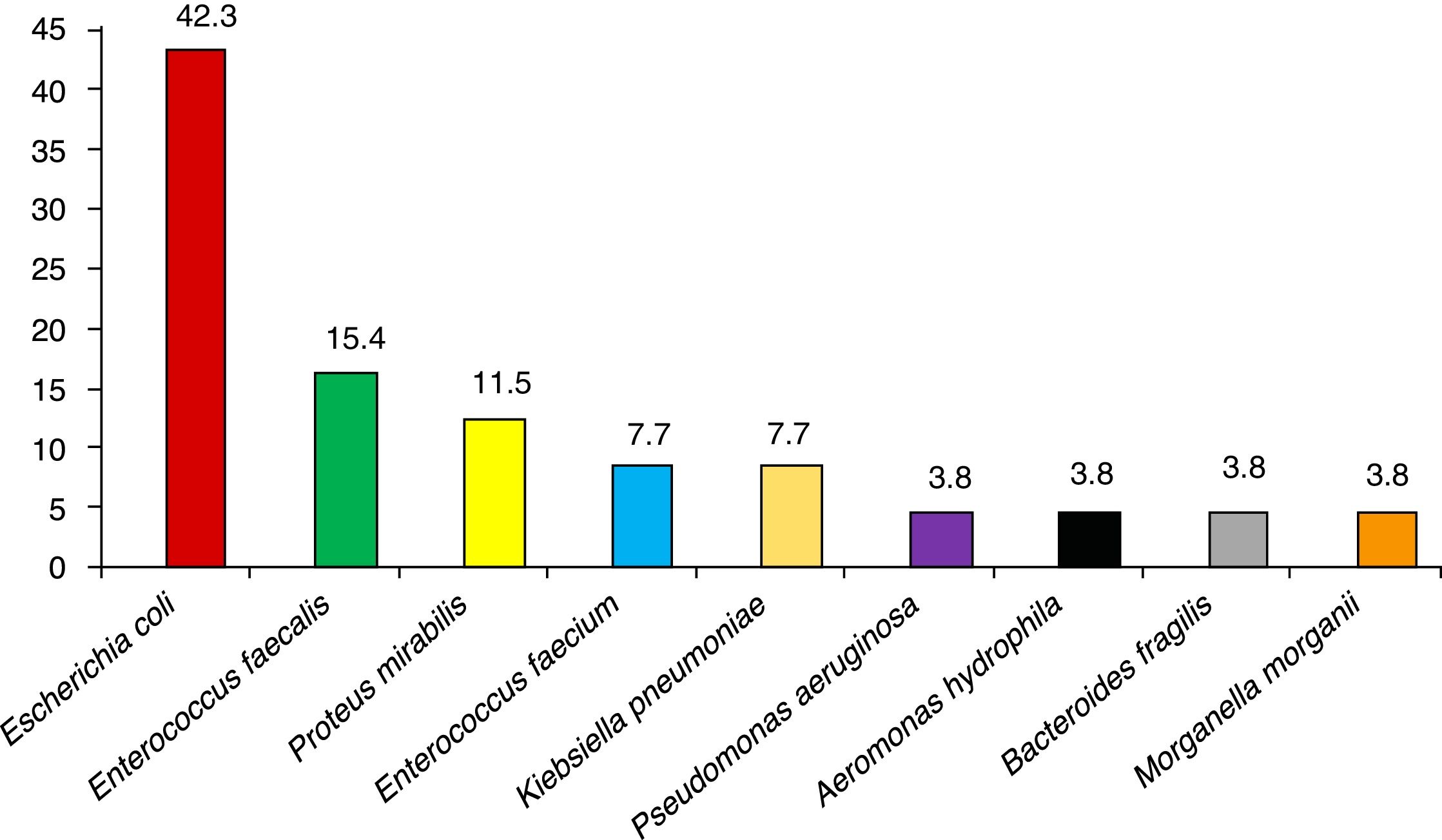

ResultsThe study included 154 patients, with a mean age of 69.5±12 years. The most common comorbidities were diabetes mellitus (24.5%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (17%) and obesity (12.6%). The overall incidence of SSI during the follow-up period was 11.9% (95% CI: 7.8–17.9) and the most frequent microorganism was Escherichia coli (57.9%). Risk factors associated with surgical wound infection in the univariate analysis were blood transfusion, drain tubes and vasoactive drug administration (P<.05).

ConclusionsThe incidence of SSI in rectal surgery was low. It is crucial to assess SSI incidence rates and to identify possible risk factors for infection. We recommend implementing surveillance and hospital control programs.

La infección de sitio quirúrgico (ISQ) es la principal causa de infección nosocomial. El objetivo de este trabajo fue estudiar la incidencia de ISQ y evaluar los factores de riesgo que la determinan en pacientes intervenidos de cirugía de recto.

MétodosEstudio de cohortes prospectivo, realizado de enero del 2013 a diciembre del 2016. Se recogieron variables relacionadas con el paciente, la intervención quirúrgica y la infección. Se calculó la incidencia de infección tras un periodo máximo de 30 días de incubación. Se evaluó el efecto de los diferentes factores de riesgo en la infección con la odds ratio ajustada con un modelo de regresión logística.

ResultadosEl estudio incluyó a 154 pacientes, con una edad media de 69,5±12 años. Las comorbilidades más habituales fueron diabetes mellitus (24,5%), enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (17%) y obesidad (12,6%). La incidencia global de ISQ durante el periodo de seguimiento fue de 11,9% (IC95%: 7,8-17,9) y el microorganismo más frecuente fue Escherichia coli (57,9%). Los factores de riesgo asociados a la infección quirúrgica en el análisis univariante fueron la transfusión sanguínea, el uso de drenajes y la administración de fármacos vasoactivas (p < 0,05).

ConclusionesLa incidencia de ISQ en cirugía de recto fue baja. Es muy importante evaluar la incidencia de infección y tratar de identificar los posibles factores de riesgo de infección. Recomendamos la implantación de programas prospectivos de vigilancia y control de la infección hospitalaria.

Healthcare-associated infections (HAI) are infections that are acquired during patient hospitalization that were not present clinically at the time of hospital admission or during the incubation period. It is estimated that 5% of patients admitted to hospital acquire an HAI,1 which is the most frequent complication during their stay. At least one-third of these infections could be prevented by different effective and cost-effective monitoring and control strategies.2 In our country, the prevalence of nosocomial infection is around 8%; Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are the most frequent causative agents.3

Surgical site infections (SSI) are infections related to an operation or surgical procedure, originating in the surgical incision or surrounding tissues. Patients who develop SSI are 60% more likely to be hospitalized in an intensive care unit, 5 times more likely to be re-admitted to the hospital, and twice as likely to die than patients without infection.4 The Nosocomial Infection Prevalence Study in Spain (Estudio de Prevalencia de las Infecciones Nosocomiales en España, or EPINE) has stated that SSI are already the number one cause of these outcomes (21.6%), ahead of respiratory and urinary infections.5 Some 60% of SSI are preventable by using evidence-based guidelines.6 Colorectal surgery presents the highest incidence of these infections, although reports in the literature vary greatly.7 A surgical site infection is the most frequent complication among patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery.8 Infection prevention should begin in the preoperative phase and during surgery, which involves determining all the risk factors that could worsen the patient's prognosis.9 The aim of our study was to study the incidence of surgical site infection and to evaluate the risk factors leading to its development in patients undergoing rectal surgery.

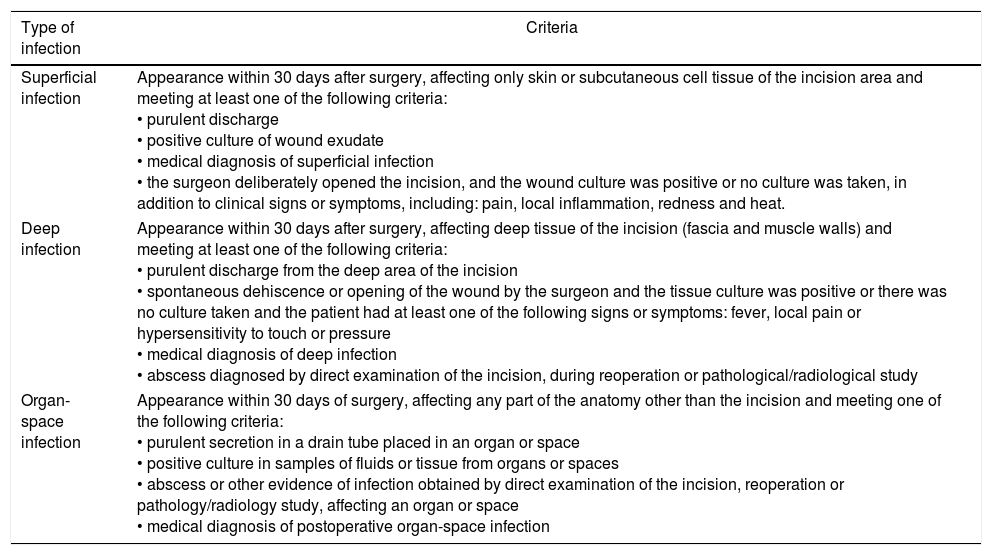

MethodsA prospective cohort study was conducted. The evaluation was carried out at the Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón (HUFA) in Madrid, Spain. The study included patients who had undergone rectal surgery in the General and Digestive Surgery Unit between January 2013 and December 2016 and had given their informed consent before the surgery. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the HUFA (CEIC HUFA). Excluded from the study were patients with suspected infection at the time of surgery and patients receiving antibiotic treatment. The sample size needed was calculated for a confidence interval of 95%, accuracy of 4.5%, estimated infection rate of 8.2%10 and an predicted loss of 5%. Based on these percentages, a study sample of 146 patients was considered necessary. The patients were selected from the surgical program and included consecutively from the beginning until the end of the study period. Surgical infections were diagnosed in accordance with the SSI criteria of the CDC. The depth of infection was defined as superficial, deep and organ-space11 (Table 1). Microbiological samples were taken from the wound or drains whenever there was clinical suspicion of infection. Data were collected for patient demographic variables and perioperative clinical situation (comorbidities, need for transfusion or drainage during the intervention, normothermia and hyperglycemia, radiotherapy or neoadjuvant chemotherapy); hospitalization variables (date of admission, diagnosis and date of discharge); preoperative preparation variables (shaving, topical antiseptic, preoperative preparation and antibiotic prophylaxis); surgery variables (date of operation, type, duration, compliance with the surgical safety checklist, ASA anesthetic risk, need for supplemental O2, vasoactive drugs and ileostomy); and SSI variables (diagnosis of infection, depth of SSI, microbiological cultures and microorganisms present). The use of preoperative antiseptic and washing was considered adequate preparation. The dependent variable in our study was the diagnosis of SSI.

SSI Classification According to CDC Criteria.

| Type of infection | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Superficial infection | Appearance within 30 days after surgery, affecting only skin or subcutaneous cell tissue of the incision area and meeting at least one of the following criteria: • purulent discharge • positive culture of wound exudate • medical diagnosis of superficial infection • the surgeon deliberately opened the incision, and the wound culture was positive or no culture was taken, in addition to clinical signs or symptoms, including: pain, local inflammation, redness and heat. |

| Deep infection | Appearance within 30 days after surgery, affecting deep tissue of the incision (fascia and muscle walls) and meeting at least one of the following criteria: • purulent discharge from the deep area of the incision • spontaneous dehiscence or opening of the wound by the surgeon and the tissue culture was positive or there was no culture taken and the patient had at least one of the following signs or symptoms: fever, local pain or hypersensitivity to touch or pressure • medical diagnosis of deep infection • abscess diagnosed by direct examination of the incision, during reoperation or pathological/radiological study |

| Organ-space infection | Appearance within 30 days of surgery, affecting any part of the anatomy other than the incision and meeting one of the following criteria: • purulent secretion in a drain tube placed in an organ or space • positive culture in samples of fluids or tissue from organs or spaces • abscess or other evidence of infection obtained by direct examination of the incision, reoperation or pathology/radiology study, affecting an organ or space • medical diagnosis of postoperative organ-space infection |

The study information was collected in a file that had been designed ad hoc and registered in a standardized and relational database. The patient was followed clinically until discharge with daily visits to evaluate the status of the surgical wound, the patient's clinical situation and the microbiology cultures requested by the General and Digestive Surgery Unit. Patients were monitored for 30 days after surgery, and the attendance of all the patients to outpatient consultations or to the emergency department was verified by reviewing the electronic patient records (Selene®, CERNER Corp., USA) or the primary care doctor records with the Horus® application (Ministry of Health, Community of Madrid). Both sets of records were reviewed 15 and 30 days after the intervention in a protocolized manner. The follow-up was carried out by the Preventive Medicine Unit, reaching the final diagnosis of infection after the joint evaluation of a preventive medicine doctor and a surgeon.

Statistical AnalysisThe quantitative variables were described with the mean±standard deviation and were compared with the Student's t-test or, if their distribution was not normal, using the Mann-Whitney U test. In the latter case, they were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). The criterion of normality was evaluated by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The qualitative variables were reported with their distribution of frequencies and compared with Pearson's χ2 test, or with Fisher's exact test when conditions were not met (expected values <5). The risk factors were studied both individually and by groups. The effect of the different risk factors for infection was evaluated by calculating the odds ratio (OR) for infection, adjusting explanatory logistic regression models with the backstep method, taking into account confusion and interaction between the various factors. In the internal calibration of the model, the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used. The analysis was performed with the SPSS v.20 statistical program, and statistical significance was considered if P<.05.

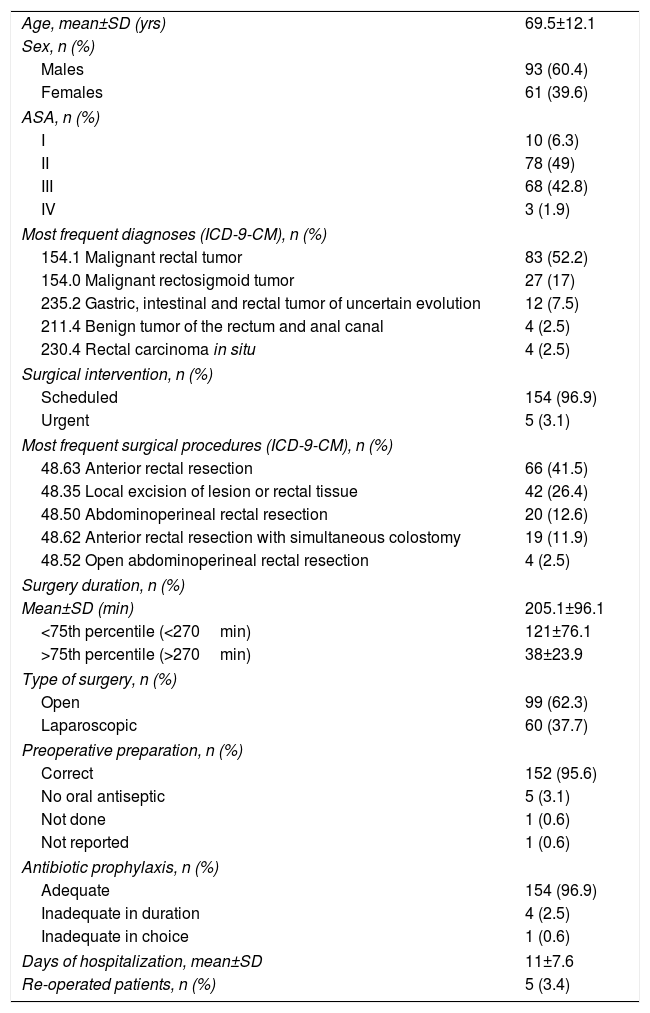

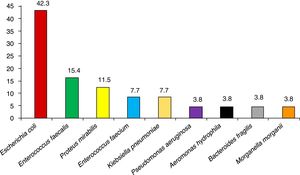

ResultsA total of 159 surgical interventions and 154 patients were included in the study. The majority of patients were men (61%); mean age was 72.3±10 years for men and 65.1±14 years for women (P<.001). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 2. Five of the patients (3.4%) underwent reoperation, and the majority presented ASA II anesthesia risk (49%) for comorbidity. The most frequent diagnosis was a malignant rectal tumor (52.2%). Most of the surgeries (96.9%) were scheduled, and anterior resection of the rectum was the most common surgical procedure in the study (41.5%). The average surgical time was 205.1±96min, and 60 surgeries were laparoscopic (37.7%). Preoperative patient preparation was performed correctly in 152 of the interventions (95.6%) and antibiotic prophylaxis was adequate in 154 (96.9%). The most frequent comorbidities in our study were diabetes mellitus (24.5%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (17%) and obesity (12.6%). The mean age of the patients with infection was 73.4±9 years, and the mean age of patients who did not develop infection was 69±12 years (P=.137). The median hospital stay for patients without infection was 8 days (IQR=6–12) and 17 days (IQR=14–24) for patients with surgical infection (P<.001). There were a total of 19 infections during the follow-up period, which meant a global SSI incidence of 11.9% (95% CI: 7.8–17.9). The infections were classified as: 12 superficial incisional (63.1%), 3 deep (15.8%) and 4 organ-space (21.1%). A descending incidence of surgical infection was observed during the 4 years of the study (16.0%, 13.0%, 8.9% and 6.7%, respectively). More specifically, 13 of the infections in total were due to a single microorganism (68.4%), while the infections in 5 patients were polymicrobial. No culture was taken in one SSI. The most frequently involved pathogens in the surgical infections were E. coli (42.3% of patients with infection), Enterococcus faecalis (15.4%) and Proteus mirabilis (11.5%). The microorganisms causing the infections can be seen in Fig. 1.

Patient Characteristics (n=154).

| Age, mean±SD (yrs) | 69.5±12.1 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Males | 93 (60.4) |

| Females | 61 (39.6) |

| ASA, n (%) | |

| I | 10 (6.3) |

| II | 78 (49) |

| III | 68 (42.8) |

| IV | 3 (1.9) |

| Most frequent diagnoses (ICD-9-CM), n (%) | |

| 154.1 Malignant rectal tumor | 83 (52.2) |

| 154.0 Malignant rectosigmoid tumor | 27 (17) |

| 235.2 Gastric, intestinal and rectal tumor of uncertain evolution | 12 (7.5) |

| 211.4 Benign tumor of the rectum and anal canal | 4 (2.5) |

| 230.4 Rectal carcinoma in situ | 4 (2.5) |

| Surgical intervention, n (%) | |

| Scheduled | 154 (96.9) |

| Urgent | 5 (3.1) |

| Most frequent surgical procedures (ICD-9-CM), n (%) | |

| 48.63 Anterior rectal resection | 66 (41.5) |

| 48.35 Local excision of lesion or rectal tissue | 42 (26.4) |

| 48.50 Abdominoperineal rectal resection | 20 (12.6) |

| 48.62 Anterior rectal resection with simultaneous colostomy | 19 (11.9) |

| 48.52 Open abdominoperineal rectal resection | 4 (2.5) |

| Surgery duration, n (%) | |

| Mean±SD (min) | 205.1±96.1 |

| <75th percentile (<270min) | 121±76.1 |

| >75th percentile (>270min) | 38±23.9 |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | |

| Open | 99 (62.3) |

| Laparoscopic | 60 (37.7) |

| Preoperative preparation, n (%) | |

| Correct | 152 (95.6) |

| No oral antiseptic | 5 (3.1) |

| Not done | 1 (0.6) |

| Not reported | 1 (0.6) |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis, n (%) | |

| Adequate | 154 (96.9) |

| Inadequate in duration | 4 (2.5) |

| Inadequate in choice | 1 (0.6) |

| Days of hospitalization, mean±SD | 11±7.6 |

| Re-operated patients, n (%) | 5 (3.4) |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists anesthetic risk classification; ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; SD: standard deviation.

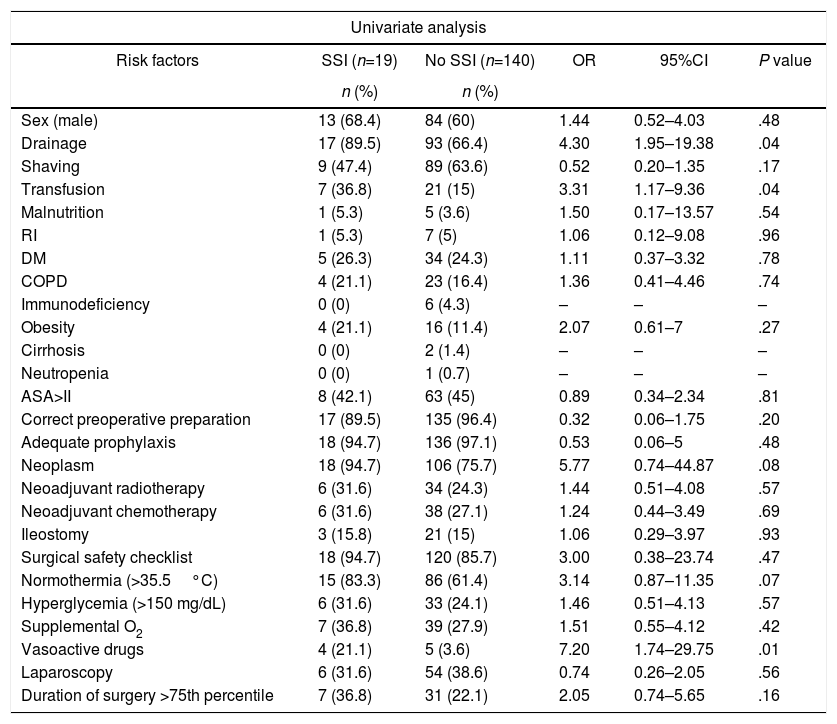

The univariate analysis showed that the risk factors associated with SSI were blood transfusion, the use of drain tubes and the administration of perioperative vasoactive drugs (P<.05). Table 3 demonstrates the univariate analysis of the various risk factors for surgical infection. In the multivariate analysis, independent risk factors for SSI were studied after being shown to be statistically significant in the univariate analysis; those with a P value ≤.2 were considered of interest due to their clinical and prognostic significance (neoplasia, normothermia, shaving, pre-surgical preparation and duration of the surgery higher than the 75th percentile). None of them was statistically significant after the multivariate analysis.

Univariate Analysis for SSI Risk Factors (n=159).

| Univariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | SSI (n=19) | No SSI (n=140) | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Sex (male) | 13 (68.4) | 84 (60) | 1.44 | 0.52–4.03 | .48 |

| Drainage | 17 (89.5) | 93 (66.4) | 4.30 | 1.95–19.38 | .04 |

| Shaving | 9 (47.4) | 89 (63.6) | 0.52 | 0.20–1.35 | .17 |

| Transfusion | 7 (36.8) | 21 (15) | 3.31 | 1.17–9.36 | .04 |

| Malnutrition | 1 (5.3) | 5 (3.6) | 1.50 | 0.17–13.57 | .54 |

| RI | 1 (5.3) | 7 (5) | 1.06 | 0.12–9.08 | .96 |

| DM | 5 (26.3) | 34 (24.3) | 1.11 | 0.37–3.32 | .78 |

| COPD | 4 (21.1) | 23 (16.4) | 1.36 | 0.41–4.46 | .74 |

| Immunodeficiency | 0 (0) | 6 (4.3) | – | – | – |

| Obesity | 4 (21.1) | 16 (11.4) | 2.07 | 0.61–7 | .27 |

| Cirrhosis | 0 (0) | 2 (1.4) | – | – | – |

| Neutropenia | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | – | – | – |

| ASA>II | 8 (42.1) | 63 (45) | 0.89 | 0.34–2.34 | .81 |

| Correct preoperative preparation | 17 (89.5) | 135 (96.4) | 0.32 | 0.06–1.75 | .20 |

| Adequate prophylaxis | 18 (94.7) | 136 (97.1) | 0.53 | 0.06–5 | .48 |

| Neoplasm | 18 (94.7) | 106 (75.7) | 5.77 | 0.74–44.87 | .08 |

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy | 6 (31.6) | 34 (24.3) | 1.44 | 0.51–4.08 | .57 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 6 (31.6) | 38 (27.1) | 1.24 | 0.44–3.49 | .69 |

| Ileostomy | 3 (15.8) | 21 (15) | 1.06 | 0.29–3.97 | .93 |

| Surgical safety checklist | 18 (94.7) | 120 (85.7) | 3.00 | 0.38–23.74 | .47 |

| Normothermia (>35.5°C) | 15 (83.3) | 86 (61.4) | 3.14 | 0.87–11.35 | .07 |

| Hyperglycemia (>150 mg/dL) | 6 (31.6) | 33 (24.1) | 1.46 | 0.51–4.13 | .57 |

| Supplemental O2 | 7 (36.8) | 39 (27.9) | 1.51 | 0.55–4.12 | .42 |

| Vasoactive drugs | 4 (21.1) | 5 (3.6) | 7.20 | 1.74–29.75 | .01 |

| Laparoscopy | 6 (31.6) | 54 (38.6) | 0.74 | 0.26–2.05 | .56 |

| Duration of surgery >75th percentile | 7 (36.8) | 31 (22.1) | 2.05 | 0.74–5.65 | .16 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Drainage | 3.47 | 0.75–16.04 | .11 |

| Shaving | 1.38 | 0.48–3.96 | .55 |

| Transfusion | 1.58 | 0.48–5.18 | .45 |

| Correct preoperative preparation | 1.78 | 0.18–17.89 | .63 |

| Neoplasm | 2.02 | 0.18–22.25 | .57 |

| Normothermia | 0.37 | 0.10–1.38 | .14 |

| Vasoactive drugs | 4.06 | 0.87–19.05 | .08 |

| Duration of surgery >75th percentile | 0.80 | 0.26–2.48 | .70 |

DM: diabetes mellitus; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CI: confidence interval; SSI: surgical site infection; RI: renal insufficiency; OR: odds ratio.

Our study shows an overall SSI incidence of 11.9% in rectal surgery (95% CI 7.8–17.9). This is less than in the VINCat study, which reported an SSI rate of 20.8% in colorectal surgery,12 or the Díaz-Agero-Pérez et al. study in colorectal surgery (14.2, 95% CI: 9.1%–21.3%).13,14 Konishi et al. showed an incidence of SSI in rectal surgery of 18%.15 Our SSI were classified as 7.5% superficial, 1.9% deep and 2.5% organ-space, which is similar to other studies consulted in the literature.16,17 In our study, the most frequently isolated microorganism was E. coli, as in other intestinal surgery series.18–20 In 72.2% of the positive cultures, a single pathogen was isolated. Rectal surgery is complex surgery, involving multiple procedures and different surgical techniques. Some publications analyze the different risk factors according to the different diseases (malignant/benign neoplasms, inflammatory bowel disease, etc.), which could partially explain the variability of significant risk factors for SSI found in the literature. This study has evaluated most of the risk factors recognized in the literature for these infections. None had statistical significance after the multivariate analysis, although the use of drain tubes, the use of perioperative vasoactive drugs and blood transfusion reached significance in the univariate analysis. The relationship between drain tubes and surgical infection is a widely debated topic. If necessary, their use should be closed and as short as possible,21 since there is increased risk of infection of the anastomosis and the retrograde contamination of the drain tube with the surrounding flora. In our study, the difference between the incidence of infection in patients with and without drain tubes was statistically significant, as is also the case in the studies by Tang et al.22 and Hoffmann et al.,23 although this was not an independent risk factor.

Our results show that the use of perioperative vasoactive drugs increases the risk of SSI, which coincides with the findings of Rojo et al.,24 where 30% of the cases in their series presented SSI after the use of said drugs, compared to 16% of the control subjects. In a French multicenter study of a cohort with 1830 patients operated on for cardiac surgery, patients who received these drugs for more than 24h had an infection risk 2.2 times higher than the rest.25 Transfusion during surgery is another risk factor classically associated with surgical infection, which would be caused by an immunomodulation that would explain the increase in infectious morbidity. Tartter et al. demonstrate the relationship between perioperative blood transfusion and postoperative infectious complications in 343 patients with colorectal disease. 24.6% of the patients who were transfused developed infectious complications, compared to 4.4% of those not transfused.26 The results of Mallol et al. in Catalonia showed a similar trend (56% vs 28%).27 Poon et al. studied a cohort of 1011 patients operated on for colorectal surgery at a university hospital, finding transfusion to be an independent risk factor for SSI (OR=2.43).28 The rates of proper antibiotic prophylaxis and preoperative preparation were very high, showing no statistical significance in terms of risk of infection. This was due to the fact that there were very few patients in whom prophylaxis and preparation were not adequate, so accurate evaluation was therefore not possible. In addition, the fundamental cause of inadequate prophylaxis was the duration of the prescription with which the patients continued covered by the antibiotic; this could influence the generation of resistances, but not the increase of infections. As for the preparation, the cause of inadequacy was due to the non-administration of the oral rinse that prevents postoperative pneumonia, but it does not influence surgical site infection. There was a significant number of patients who had undergone laparoscopic surgery, and we found no differences in the incidence of infection between the open and laparoscopic techniques, although this relationship has been proven in the scientific literature.29,30

When trying to assess the incidence of SSI, the ideal method is to conduct prospective cohort studies (level of scientific evidence grade 2), since retrospective records have methodological limitations. When retrospectively evaluating patients, there is no guarantee that all are included in the study (selection bias), or that information for all variables or for all cultures is collected (in case of suspected infection, for their confirmation) (information bias). Regarding the limitations of our study, we have to consider several factors. Rectal surgery is less frequent than other surgical procedures of the digestive system and, in order to accurately estimate the incidence of infection and avoid random biases, the sample size was calculated according to the expected incidence of infection based on other studies. It should also be noted that, although the cohort was designed and collected prospectively, certain data were not recorded for all patients (perioperative normothermia and hyperglycemia) and could not be assessed accurately. We tried to control for losses by estimating a percentage of possible losses in the sample size so it would not lose statistical power. In the risk factor analysis, we have evaluated numerous variables related with the surgical intervention. However, an important factor for the development of SSI is the experience of the surgeon,27,31 a variable that is difficult to quantify at a university hospital, where there is greater turnover and several surgeons may be involved in each surgery, as well as doctors in training. Therefore, we did not evaluate surgeon experience in this study. In conclusion, the incidence of SSI in rectal surgery was low, and it is very important to evaluate the incidence of infection and try to identify possible risk factors for infection. To this end, we recommend the implementation of prospective programs for the surveillance and control of hospital infection, which would enable us to evaluate the incidence of infection on a continuous basis and to adopt preventive measures for factors that are potentially modifiable.

FundingThis study was financed with European Regional Development Funds (Fondos Europeos para el Desarrollo Regional, FEDER) and a Spanish Healthcare Research Fund (Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, FIS) as part of research projects PI11/01272 and PI14/01136.

AuthorshipDr. Enrique Colás-Ruiz participated in the study design, data collection, article composition, critical review and approval of the final manuscript.

Dr. Juan Antonio Del-Moral-Luque participated in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results, article composition, critical review and approval of the final manuscript.

Dr. Pablo Gil-Yonte participated in the study design, data collection, article composition, critical review and approval of the final manuscript.

Dr. José María Fernández-Cebrián participated in the study design, article composition, critical review and approval of the final manuscript.

Dr. Marcos Alonso-García participated in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results, article composition, critical review and approval of the final manuscript.

Dra. María Concepción Villar-del-Campo participated in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results, critical review and approval of the final manuscript.

Dr. Manuel Durán-Poveda participated in the study design, article composition, critical review and approval of the final manuscript.

Dr. Gil Rodríguez-Caravaca participated in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results, article composition, critical review and approval of the final manuscript.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Colás-Ruiz E, Del-Moral-Luque JA, Gil-Yonte P, Fernández-Cebrián JM, Alonso-García M, Villar-del-Campo MC, et al. Incidencia de infección de sitio quirúrgico y factores de riesgo en cirugía de recto. Estudio de cohortes prospectivo. Cir Esp. 2018;96:640–647.