The objective of this study is to assess whether the results of loop ileostomy closure in terms of morbidity and hospital stay are influenced by the type of anastomosis and suture used.

MethodAll patients who underwent loop ileostomy closure were reviewed. A retrospective cohort study comparing morbidity and hospital stay according to the type of anastomosis (TT/LL) and the type of suture (hand sewn/mechanical) was performed.

ResultsFrom January 2003 to November 2011 a total of 167 loop ileostomy closures were analysed. The groups were: type of anastomosis (TT 95/LL 72) and type of suture (manual 105/stapled 62). In 76% of the observed population the underlying disease was cancer. Mortality occurred in one case. The stratified morbidity analysis by type of complications showed no significant differences between the groups in terms of local (7.4% TT, LL 8.3%, 6.7% hand sewn, stapled 9.7%), general (TT 9.5%, 16.7% LL, hand sewn 6.7%, 6.5% stapled) and surgical (TT 15.8%, 19.4% LL, hand sewn 17.1%, 17.7% stapled) complications, nor in the rate of reoperations (TT 6.3%, 6.9% LL, hand sewn 6.7%, 6.5% stapled) and hospital stay in days (TT 7.8, 8 LL, hand sewn 8.6, stapled 6.7).

ConclusionsClosure of loop ileostomy can be performed regardless of the type of suture or anastomosis used, with the same rate of morbidity and hospital stay.

El objetivo de este trabajo es valorar si los resultados del cierre de ileostomía en asa en términos de morbimortalidad y estancia hospitalaria se ven influidos por el tipo de anastomosis y de sutura empleada.

MétodoSe ha revisado el grupo de pacientes intervenidos por cierre de ileostomía en asa, y se ha realizado un análisis retrospectivo de cohortes comparando la morbimortalidad y estancia hospitalaria en función del tipo de anastomosis (TT o LL) y del tipo de sutura (manual/mecánica).

ResultadosDesde enero del 2003 a noviembre del 2011 se han analizado 167 procedimientos de reconstrucción del tránsito en ileostomía en asa. La distribución por grupos fue: tipo de anastomosis (TT 95; LL 72) y tipo de sutura (manual 105; mecánica 62). En el 76% de la población observada la enfermedad de base fue de origen oncológico. La mortalidad ha sido de un caso. El análisis de morbilidad estratificado por tipo de complicaciones no mostró diferencias significativas entre los grupos en cuanto a complicaciones locales (TT 7,4%; LL 8,3%; manual 6,7%; mecánica 9,7%), generales (TT 9,5%; LL 16,7%; manual 6,7%; mecánica 6,5%) y quirúrgicas (TT 15,8%; LL 19,4%; manual 17,1%; mecánica 17,7%), ni en el índice de reintervención (TT 6,3%; LL 6,9%; manual 6,7%; mecánica 6,5%) ni estancia hospitalaria expresada en días (TT 7,8; LL 8; manual 8,6; mecánica 6,7).

ConclusionesLa reconstrucción del tránsito intestinal en las ileostomías en asa puede realizarse independientemente del tipo de anastomosis y de sutura empleadas, con la misma tasa de morbimortalidad y estancia hospitalaria.

Loop ileostomy closure is one alternative for intestinal content transit derivation. Due to its many advantages, including its simple performance,1,2 lower morbidity rate3 compared with colostomies,4–6 and better quality of life,7,8 it is proposed as the surgical option of choice instead of lateral colostomy.

Ileostomy closure is a simple procedure with a relatively high rate of complications, including postoperative ileus, mechanical intestinal obstruction, anastomotic dehiscence and surgical site infection.4,8 A considerable percentage of patients, between 7% and 30%, depending on the series,9 also develop hernia.

Increased use of mechanical sutures for anastomosis is beneficial for the patient and surgeon, in terms of morbimortality, resulting in safe and easy very low anastomosis. This situation, together with the use of neoadjuvant radiotherapy in rectal cancer treatment, has led to an increase in the number of ileostomies performed in our hospitals. The use of mechanical suturing devices has also increased, and they are also are applied in loop ileostomy closure.

There has been a significant increase in the use of mechanical sutures in our unit for loop ileostomy closure, especially since 2009 with the arrival of younger surgeons to the unit. This increase, together with its subsequent increase in cost, led us to consider whether the type of anastomosis and suture actually offered benefits to the patients to justify their use in this surgical procedure.

The aim of our study was to assess whether the results of loop ileostomy closure in terms of morbimortality and hospital stay are influenced by the type of anastomosis and suture used.

MethodA retrospective, single centre comparative cohort study was performed. All patients who underwent loop ileostomy closure from January 2003 until December 2011 were included. Inclusion was irrespective of the primary surgery.

All patients underwent a pre-operative study following hospital protocol, as well as a barium and transanal endoscopy to rule out anastomotic leaks or stenosis which would contraindicate stoma closure.

Two main variables were analysed: type of anastomosis (TA) and type of suture used (TS). These constitute 2 separate study groups. The TA group includes 2 subgroups: end-to-end anastomosis (TT) and side-to-side (LL) anastomosis. The TS groups also contain 2 sub-groups: manual suture (TSMAN) and mechanical suture (TSMEC), the latter performed with 3 GIA staplers (75mm, 3.0mm×3.85mm, Ethicon Endo-Surgery™).

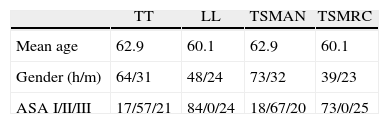

The homogeneity of the 2 groups was assessed prior to review, establishing and comparing several equality criteria such as age, gender and the American Association of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification.

The parameters analysed were operative mortality (during the first 30 days after surgery), morbimortality and hospital stay, which was estimated as the difference between hospital discharge and date of surgery.

Morbidity analysis was performed by combining complications into 3 groups: local complications (haematoma, seroma) general (cardiovascular, nephrourinary, respiratory, vascular and digestive) and surgical. The latter were defined as: anastomosis dehiscence (any clinical or radiological evidence of contrast or perianastomotic air leakage), anastomosis bleeding (appearance of rectorrhagia with or without haemodynamic instability, together with the need to perform a separate CT-angiography, regardless of result), paralytic ileus (intestinal paralysis beyond the 5th day after surgery) and lastly the reoperation rate (performed during the first 30 post-operative days).

All patients were analysed according to the principle of intention to treat. The qualitative variables were presented using absolute and relative frequencies and were calculated according to the chi square test with Yates correction for continuity. Quantitative variables were presented using mean and typical deviation and were calculated using the Student T-test and Mann–Whitney U test. P was considered significant under .5.

ResultsPatient CharacteristicsOf the 172 patients who underwent surgery, 5 were excluded. These patients presented an incisional hernia of the previous laparotomy, which was simultaneously repaired at the stoma closure procedure.

The final study group consisted of 167 patients, 105 (62.8%) of whom were male and 62 (37.1%), female. Mean age was 60.1. In 126 (76%) patients the underlying disease was cancer. In 28 (16%) it was inflammatory bowel disease and in 19 (8%), other benign conditions.

In the type of anastomosis (TA) analysis, 95 (56.8%) underwent a TT anastomosis and 72 (43.1%) an LL anastomosis; with regard to the type of suture used (TS), 105 patients (62.8%) had MAN and 62 (37.1%) MEC.

No significant differences were found regarding homogeneity criteria established between the groups created, and they were therefore considered comparable (Table 1).

The time period between creation of the stoma and its closure was 1–12 months with an average of 6 months.

Mortality occurred in one ASA III patient with cancer (1.6%) aged 81, who underwent mechanical LL anastomosis and who died immediately after surgery, due to anastomotic leak, peritonitis and increased kidney failure.

During surgery, an incisional hernia was found in 21.7% of patients.

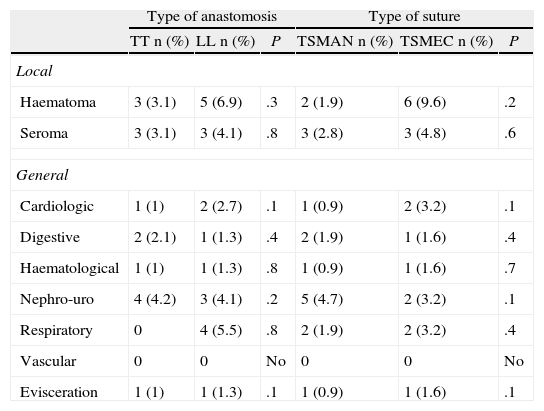

The most frequent local complication was seroma and haematoma. There was an increase in the percentage of haematomas in LL anastomosis and mechanical suture patients. The most frequent general complication was nephro-urological (urinary infection, severe urinary retention) in both groups. An increase of respiratory type complications in patients with LL anastomosis and mechanical suture was observed, with no significant differences being found between the 2 groups (Table 2).

Local and General Complications.

| Type of anastomosis | Type of suture | |||||

| TT n (%) | LL n (%) | P | TSMAN n (%) | TSMEC n (%) | P | |

| Local | ||||||

| Haematoma | 3 (3.1) | 5 (6.9) | .3 | 2 (1.9) | 6 (9.6) | .2 |

| Seroma | 3 (3.1) | 3 (4.1) | .8 | 3 (2.8) | 3 (4.8) | .6 |

| General | ||||||

| Cardiologic | 1 (1) | 2 (2.7) | .1 | 1 (0.9) | 2 (3.2) | .1 |

| Digestive | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.3) | .4 | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.6) | .4 |

| Haematological | 1 (1) | 1 (1.3) | .8 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.6) | .7 |

| Nephro-uro | 4 (4.2) | 3 (4.1) | .2 | 5 (4.7) | 2 (3.2) | .1 |

| Respiratory | 0 | 4 (5.5) | .8 | 2 (1.9) | 2 (3.2) | .4 |

| Vascular | 0 | 0 | No | 0 | 0 | No |

| Evisceration | 1 (1) | 1 (1.3) | .1 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.6) | .1 |

LL: type of side-to-side anastomosis; TT: type of end-to-end anastomosis; TSMAN: type of manual suture; TSMEC: type of mechanical suture.

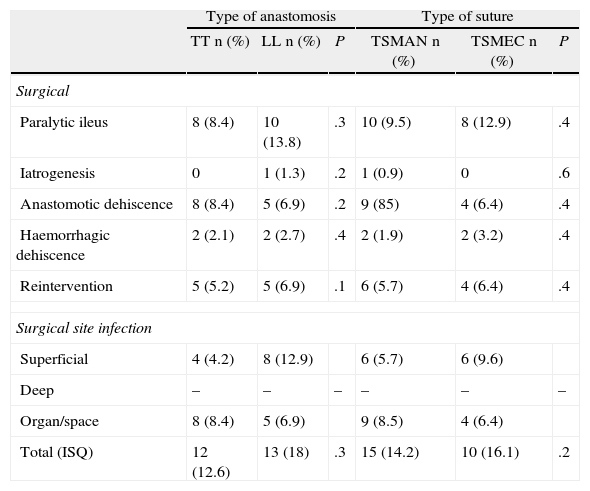

The most frequent surgical complication was paralytic ileus, followed by anastomotic dehiscence and haemorrhage of the anastomosis. Reoperation rate was between 5.2% and 6.9%, with no significant differences between the 2 groups. The most frequent cause of reoperation was anastomotic leak and the formation of abdominal abscesses not attributable to percutaneous drainage.

Surgical site infection analysis showed an increase in superficial infection in patients with LL anastomosis and mechanical suture, as well as an increase in organ-site infection in patients who underwent TT anastomosis and MAN. However, no significant differences were observed, with around 15% incidence in both groups (Table 3). No significant differences were found regarding mean hospital stay in the different groups. Mean stay was 5 days.

Surgical Complications.

| Type of anastomosis | Type of suture | |||||

| TT n (%) | LL n (%) | P | TSMAN n (%) | TSMEC n (%) | P | |

| Surgical | ||||||

| Paralytic ileus | 8 (8.4) | 10 (13.8) | .3 | 10 (9.5) | 8 (12.9) | .4 |

| Iatrogenesis | 0 | 1 (1.3) | .2 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | .6 |

| Anastomotic dehiscence | 8 (8.4) | 5 (6.9) | .2 | 9 (85) | 4 (6.4) | .4 |

| Haemorrhagic dehiscence | 2 (2.1) | 2 (2.7) | .4 | 2 (1.9) | 2 (3.2) | .4 |

| Reintervention | 5 (5.2) | 5 (6.9) | .1 | 6 (5.7) | 4 (6.4) | .4 |

| Surgical site infection | ||||||

| Superficial | 4 (4.2) | 8 (12.9) | 6 (5.7) | 6 (9.6) | ||

| Deep | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Organ/space | 8 (8.4) | 5 (6.9) | 9 (8.5) | 4 (6.4) | ||

| Total (ISQ) | 12 (12.6) | 13 (18) | .3 | 15 (14.2) | 10 (16.1) | .2 |

LL: type of side-to-side anastomosis; TT: type of end-to-end anastomosis; TSMAN: type of manual suture; TSMEC: type of mechanical suture.

Published studies associate ileostomy closure with morbidity rates within a range between 9.3 and 45.9%10–15 and a mortality between 1.7 and 6.4%.16,17 The series published study few patients with a follow-up of associated morbimortality under a period of 30 postoperative days.

In our review, with an appropriate number of cases, a similar morbidity rate is observed to that published by other authors, although our attention is drawn to the high percentage of peristomal hernias found (21%). These are within the published range (from 9 to 51%),18–21 but we are considering the need for review of the post-operative herniation incidence in the mid and long term after ileostomy closure, since in all cases simple closure of the abdominal wall was performed.

Mortality corresponds to the majority of the reviewed series, and is between 0 and 4%.16,22–24

No significant differences were observed in the morbidity variables observed, or in the type of suture, or anastomosis used.

One aspect which could promote use of mechanical sutures is the belief that LL anastomoses create a larger intestinal lumen, which could favour the reduction of postoperative ileus25,26 and lower incidence of suture dehiscence.27 However, in our series, coinciding with other authors,28,29 we found no differences regarding the technique used, anastomosis leak frequency, or appearance of postoperative ileus.

Mean hospital stay was 5 days. TA and suture technique did not appear to influence this aspect.

Although ileostomy closure is a technically simple intervention we believe it should not be performed as outpatient surgery, which has been proposed in several studies, due to the complications observed by different authors.30,31 One reason is the considerable incidence of suture dehiscence of between 8.5% and 6.4% in our series, and a high number of patients with nausea, vomiting, and postoperative ileus, which could lead to considerable hospital readmission.

Although ileostomy closure is recommended before 8.5 weeks,32 in our series it was performed later, probably due to the high number of cancer patients14 (76%). Most patients required chemotherapy after initial surgery which is why ileostomy closure was delayed. Other major causes for delay were complications from the higher rate of surgical site infection during primary tumour surgery,6,7,13 and both administrative and structural difficulties in assigning an operating room once all preoperative studies were completed. Further emphasis should probably be placed on early closure in some patients, as proposed by several authors.33–36

Regarding study limitations, we should note that this was a cohort study with a short term follow-up, which was why later complications such as stenosis of the anastomosis and post-closure hernia could not be assessed. Although obstruction could be related to TA, herniation would be more related to the type of abdominal wall closure type, even if it were similar in all groups. The lack of any economical analysis is another limitation, bearing in mind that a lateral ileostomy closure procedure with mechanical suture requires a device and at least 3 staples (2 75mm and one 45mm), which increase the price of the procedure by approximately 1000 Euros per operated patient.

To conclude, the results of our study showed no differences regarding morbimortality or hospital stay as a result of the TA or TS performed in lateral ileostomy closure. Based on these results, we propose the routine use of manual anastomosis, regardless of the TA, since mechanical suture material has not proved superior and would probably drive up the costs of the procedure.

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare there is no conflict of interest in this article.

Please cite this article as: Vallribera Valls F, Villanueva Figueredo B, Jiménez Gómez LM, Espín Bassany E, Sánchez Martinez JL, Martí Gallostra M, et al. Evolución del cierre de ileostomía en una unidad de cirugía colorrectal. Análisis comparativo según la técnica. Cir Esp. 2014;92:182–187.

This paper was presented at the XVI National Session of the Foundation of the Spanish Association of Coloproctology in Seville, 9–11 May 2012.