The veracity of the conclusions reached by systematic reviews (SRs) and meta-analyses is largely determined by the presence of bias in the empirical studies undertaken. For this reason, the risk of bias analysis has become an unavoidable stage in the process of conducting SRs and meta-analysis, the results of which must be taken into account in the interpretation of the findings.

In the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions, systematic bias or error is defined as the deviation of the results of a study from its true effect, either of an intervention (or of a factor of exposure, beyond the scope of the intervention). The degree of bias may be variable and the effect may be over- or underestimated.1 Factors related to the design and conduct of the study and the analysis of the data are what give rise to these threats to internal validity.

Since it is impossible to know for sure to what extent the results of a study have been affected by bias, we speak of “risk of bias”. It is important to differentiate this concept from others. such as methodological quality (reporting standards). The first concept refers to scales (usually quantitative) that assess the characteristics of a study design. Although these have been widely used to evaluate the studies included in a review, they are used less and less due to their controversial results.2 The second concept refers to the standards for publication of research reports and consists mostly of checklists of information that should be included in different types of studies: an example would be the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guideline for randomised clinical trials.3

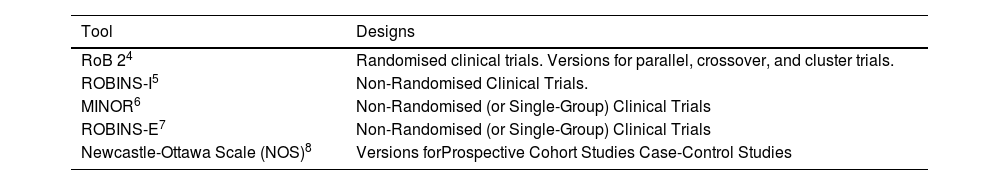

Assessment of risk of bias in a study should take into account the design of the study and the effect (or outcome) of interest in the review. Depending on the design of the study, the appropriate tool for assessing the risk of bias will be selected. Table 1 presents some commonly used tools for assessing the risk of bias in different designs.

Tools to assess the risk of bias in SRs and meta-analyses.

| Tool | Designs |

|---|---|

| RoB 24 | Randomised clinical trials. Versions for parallel, crossover, and cluster trials. |

| ROBINS-I5 | Non-Randomised Clinical Trials. |

| MINOR6 | Non-Randomised (or Single-Group) Clinical Trials |

| ROBINS-E7 | Non-Randomised (or Single-Group) Clinical Trials |

| Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)8 | Versions forProspective Cohort Studies Case-Control Studies |

MINOR: Methodological index for non-randomized studies; NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; ROBINS-E: Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Exposure; ROBINS-I: Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Interventions; RoB 2: Revised tool for Risk of Bias in randomized trials; SRs: Systematic Reviews.

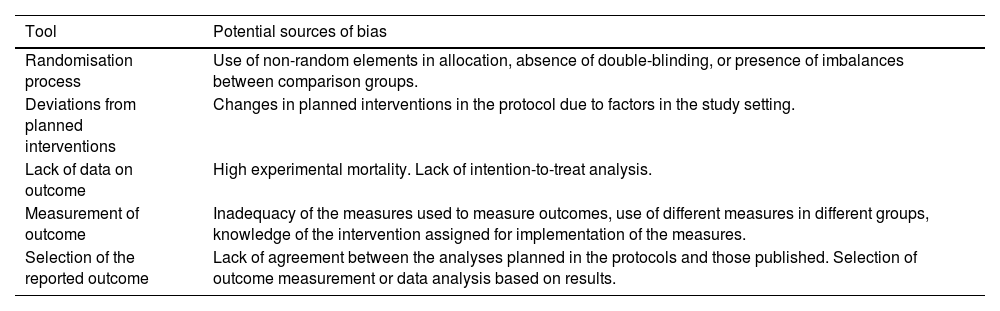

Interventional studies are one of the main sources of evidence in the field of surgery. Randomised clinical trials are intervention studies whose design offers the greatest assurance of internal validity, although this does not mean that they are free of bias. The Cochrane Collaboration has identified different sources of bias in randomised trials: bias related to the randomisation process, deviations from planned interventions, lack of data on results, measurement of results, and selection of the reported outcome9 (Table 2).

Tools for the assessment of the risk of bias in randomised clinical trials in the Cochrane Collaboration RoB 2 tool.

| Tool | Potential sources of bias |

|---|---|

| Randomisation process | Use of non-random elements in allocation, absence of double-blinding, or presence of imbalances between comparison groups. |

| Deviations from planned interventions | Changes in planned interventions in the protocol due to factors in the study setting. |

| Lack of data on outcome | High experimental mortality. Lack of intention-to-treat analysis. |

| Measurement of outcome | Inadequacy of the measures used to measure outcomes, use of different measures in different groups, knowledge of the intervention assigned for implementation of the measures. |

| Selection of the reported outcome | Lack of agreement between the analyses planned in the protocols and those published. Selection of outcome measurement or data analysis based on results. |

RoB 2: Revised tool for Risk of Bias in randomized trials.

Likewise, the difficulty in conducting randomised studies in the field of surgery has led to the development of other specific tools in this field for assessing the risk of bias in quasi-experimental intervention studies with or without groups for comparison.6

Both in medicine in general, and in the field of surgery in particular, environmental, social, and behavioural factors have important effects on health,7 which is why much of the evidence comes from research into non-experimental methodologies. The Newcastle-Ottawa scales are among the most widely used to date in cohort and case-control studies, in which the aspects considered most relevant for the assessment of risk of bias are the selection of interest groups, the comparability of groups and the determination of exposure.8

One of the main difficulties in assessing the risk of bias in a study is the lack of information. For example, although the authors of a clinical trial define it as randomised, the procedures for randomising and concealing the experimental condition from participants and researchers are not described in detail.10 A better understanding of potential sources of bias, as well as efforts to minimise their effects, will lead to results in empirical studies, and thus SRs and meta-analyses, which more accurately reflect the true effect sought after.

Please cite this article as: Iniesta-Sepúlveda M, Ríos A. La evaluación del riesgo de sesgo en los estudios incluidos en revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Cir Esp. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2024.04.013