The value of inflammatory proteins, interleukin-6 and alpha-1-acid glycoprotein as prognostic factors in elderly people undergoing surgery has not been determined yet.

ObjectiveTo know whether preoperatively determined inflammatory markers may predict the postoperative outcome of elderly patients undergoing surgery. A scoring system for predicting postoperative morbidity was assessed.

MethodsHospital-based observational prospective study, with geriatric surgical patients. Preoperative determination of following data: age, gender, scheduled or urgent operation, comorbid diseases, malignancy, physical, mental and nutritional profile. Biochemical markers of inflammation, C Reactive Protein, interleukin-6, and alpha-1-acid glycoprotein were also studied. Preoperative data and postoperative complications were recorded. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to obtain a morbidity risk prediction model.

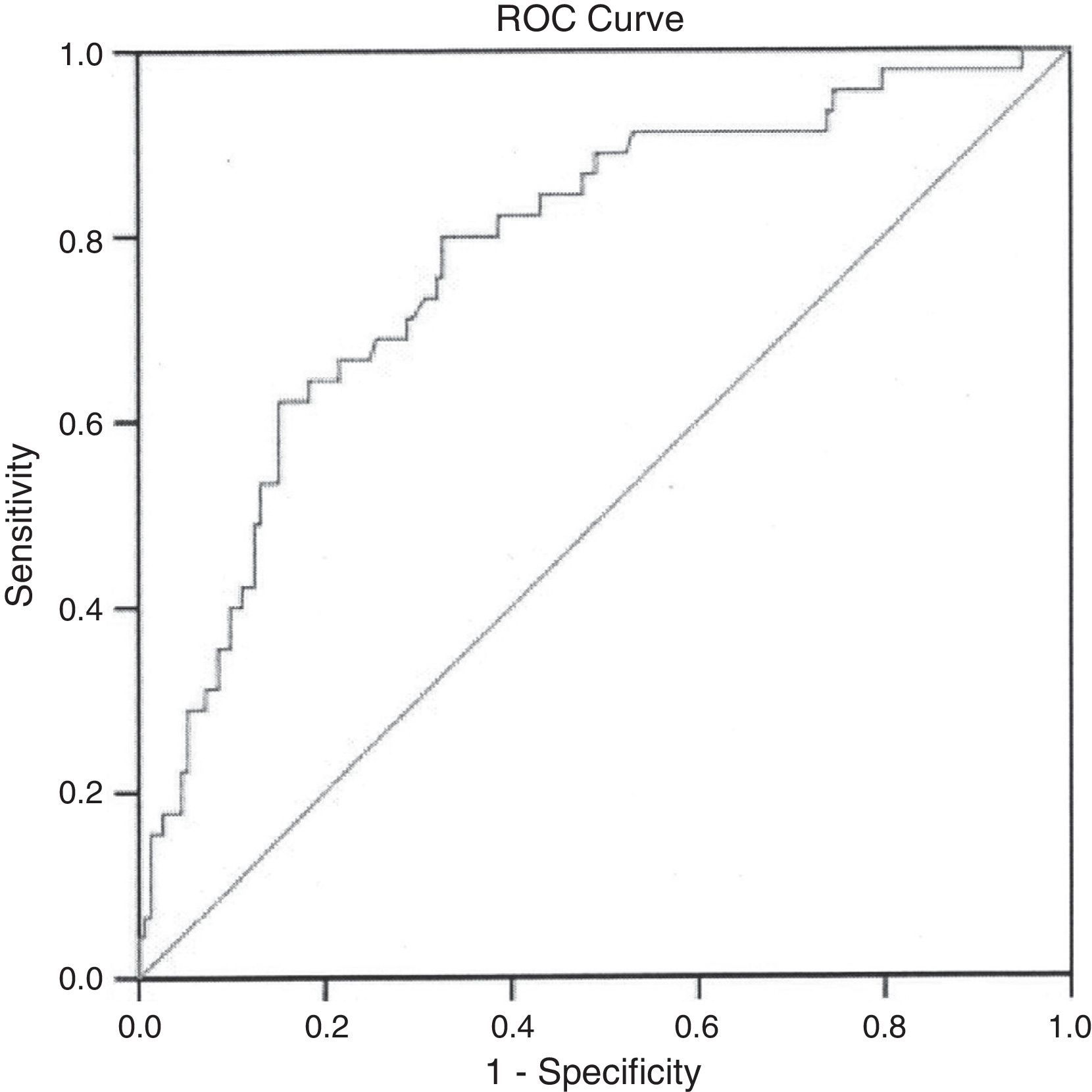

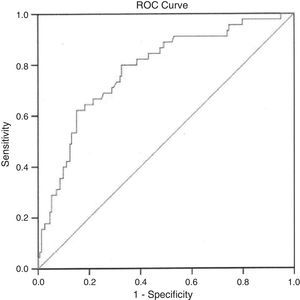

ResultsA total of 225 patients were included. Fifty-five patients (24.4%) had postoperative complications, with a mortality rate of 5.3%. Binary logistic regression analysis showed an independent relation between morbidity and the variables malignancy, alpha-1-acid glycoprotein and interleukin-6. The risk (R) of postoperative morbidity adjusted by age was calculated. The model showed a 22.2% sensitivity, 94.8% specificity, and a percentage of correct classification of 78.3%. The area under the ROC curve was 0.781 (95% CI: 0.703–0.858).

ConclusionsAn age-adjusted equation for predicting 30-day morbidity that included malignancy, serum IL-6 and alpha 1-acid glycoprotein levels may be useful for risk assessment in octogenarian surgical patients.

La utilidad de proteínas mediadoras de la inflamación (alfa-1 glucoproteína e interleucina-6) en la predicción de complicaciones en personas mayores intervenidas quirúrgicamente no está suficientemente establecida.

ObjetivoDeterminar si los niveles preoperatorios de estos marcadores de inflamación se correlacionan con complicaciones postoperatorias en pacientes ancianos, obteniendo las bases para la elaboración de un sistema de predicción de riesgo quirúrgico.

MétodosEstudio prospectivo observacional en pacientes mayores de 80 años, intervenidos quirúrgicamente de procedimientos de cirugía general.

Se determinaron preoperatoriamente: edad, sexo, tipo de cirugía, existencia de malignidad, comorbilidades asociadas, el estado físico, mental y nutricional de los pacientes.

También marcadores de inflamación: proteína C reactiva, interleucina-6, alfa-1-ácido glucoproteína. Se registraron las complicaciones postoperatorias. Se realizó un análisis multivariante para la obtención de un modelo de predicción de riesgo.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 225 pacientes. De ellos, 55 pacientes (24.4%) presentaron complicaciones, con una mortalidad del 5,3%. En el análisis multivariante, las variables interleucina-6, alfa-1-ácido glucoproteína y la presencia de malignidad se asociaron de forma independiente con la existencia de morbilidad. Se utilizaron estas variables para el cálculo de riesgo (R) de morbilidad postoperatoria ajustado por edad. El modelo mostró una sensibilidad del 22,2%, con 94,8% de especificidad, y un porcentaje de correctos clasificados del 78,3%. Área bajo la curva ROC: 0,781 (95% CI: 0,703–0,858).

ConclusionesLa valoración conjunta preoperatoria de la existencia de malignidad, niveles de alfa-1-ácido glucoproteína e interleucina-6 puede ser de utilidad en el cálculo del riesgo quirúrgico en ancianos.

Elderly people represent the fastest-growing population group in developed countries. Current estimates indicate that by 2050, 9% of Europeans will be over 80 years old1; therefore, it can be expected that the demand for medical-surgical care will continue to increase in the coming decades. Although the performance of surgical treatments in elderly patients is increasingly widespread,2–4 there is an obvious increase in the perioperative morbidity and mortality associated with age. This fact has been attributed to several already proven factors, such as poor nutritional status, the frequent practice of emergency surgery or the presence of concomitant diseases.5–10

On the other hand, many debilitating chronic diseases are associated with activation of a systemic inflammatory condition, which can be measured by increased levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), alpha-1-acid glycoprotein (AGP) or other proinflammatory molecules such as interleukin-6 (IL-6). These studies relate the levels of these acute-phase proteins with an increased risk of early death in healthy elderly people, as in the case of CPR and IL-6, or with the incidence of mortality in institutionalised elderly people in the case of AGP.11–13

Therefore, there is evidence that leads us to think that these inflammatory markers reflect underlying pathological processes, not always detected, which may contribute to increased risk of mortality in the elderly.14–16

Out of these age-related inflammatory markers, only IL-6 has been studied as a prognostic marker in patients undergoing surgery, although in a restricted manner in a colon surgery study.17

Focusing on the elderly patient who will require surgery, it should be remembered that there is a wide range of factors (nutritional status, mental status, comorbidities, etc.) whose knowledge can help predict preoperatively the possibility of postoperative complications. However, the potential usefulness of such factors as a whole to predict postoperative complications in the specific group composed of elderly patients has not been assessed yet. On the other hand, the role of these proinflammatory molecules that are associated with a poor vital prognosis in the elderly has not been evaluated in elderly patients treated with surgery either.

The primary purpose of this study is to know which preoperatively determined variables are associated with postoperative complications in elderly patients treated with surgery. As a result of the information obtained, its secondary purpose would be to provide information with a view to developing a surgical risk assessment system, which can help to preoperatively make the most suitable therapeutic decisions for each particular patient.

Patients and MethodsAn observational prospective study was conducted. We included patients aged 80 and over who underwent consecutive general surgery procedures (either elective or urgent) in the General Surgery Department of an acute care hospital with 200 beds between January 2008 and October 2010.

Patients classified by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) as belonging to risk group V or patients in the terminal stage of their disease were excluded from the study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and all the participants gave their informed consent in writing.

In all patients, the following preoperative variables were recorded:

Age, sex, scheduled or urgent surgery, comorbid diseases, existence of malignancy, vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure), laboratory data (complete blood count, standard chemistry panel, total protein, albumin, transferrin) and biochemical markers of inflammation, including the serum CRP, IL-6 and AGP levels.

The Charlson comorbidity index,18 the assessment of the mental status through the Portable Short Questionnaire (SPMSQ),19 the Barthel index,20 the ASA physical status,21 the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12)22 and the Mini Nutritional Assessment test (MNA test)23 were determined.

All the postoperative complications were collected, following the definitions proposed by Copeland et al.24 Mortality was observed 30 days after surgery, including both deaths in the hospital as well as those occurring after discharge. The Clavien–Dindo scale25 was used to classify complications depending on their severity degree. Grades III and IV of the Clavien–Dindo classification were considered serious complications.

Statistical AnalysisPostoperative morbidity was considered as the dependent variable, and the statistical analysis was repeated for all the patients studied, including two definitions of morbidity: (1) any type of postoperative complication including mild complications; (2) only serious postoperative complications (Clavien–Dindo grades III–IV). Under both assumptions, the cases of mortality in the series were included. Comparisons between groups (patients with and without postoperative complications) were performed using the Student's t-test and the chi-square test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The Mann–Whitney test and Fisher's exact test were used alternately as parametric options.

Out of the total number of patients, three different groups were established, on the basis of the diseases that presented similar risks of complications:

GA: bowel surgery group mostly made up of patients undergoing colon surgery with an expected morbidity of more than 30%.26

GB: biliary surgery group mostly made up of patients undergoing gallbladder surgery, either urgent or scheduled, with an expected morbidity of 15%.27

GC: which included various diseases, mostly cases of abdominal wall surgery and expected levels of complications of 3%–5%.28

This division into groups was useful to determine whether those variables which are associated with complications present more altered values in the group in which increased morbidity is expected (GA).

In another secondary analysis, those patients who underwent urgent surgery were excluded from the overall group. The individual analysis of the group that underwent scheduled surgery and the variables resulting from it were used to verify whether the inclusion of patients undergoing urgent surgery could bias the outcomes of the study.

Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

The variables that showed statistical significance in the univariate analysis were subjected to a multivariate analysis in order to obtain those that could be included in a postoperative risk calculation equation. Sensitivity, specificity and percentage of correct classification were established. The area under the curve (ROC) was identified to demonstrate the discriminatory power of the equation. The calibration of the model was tested by means of the Hosmer Lemeshow test. The statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics version 19.0.

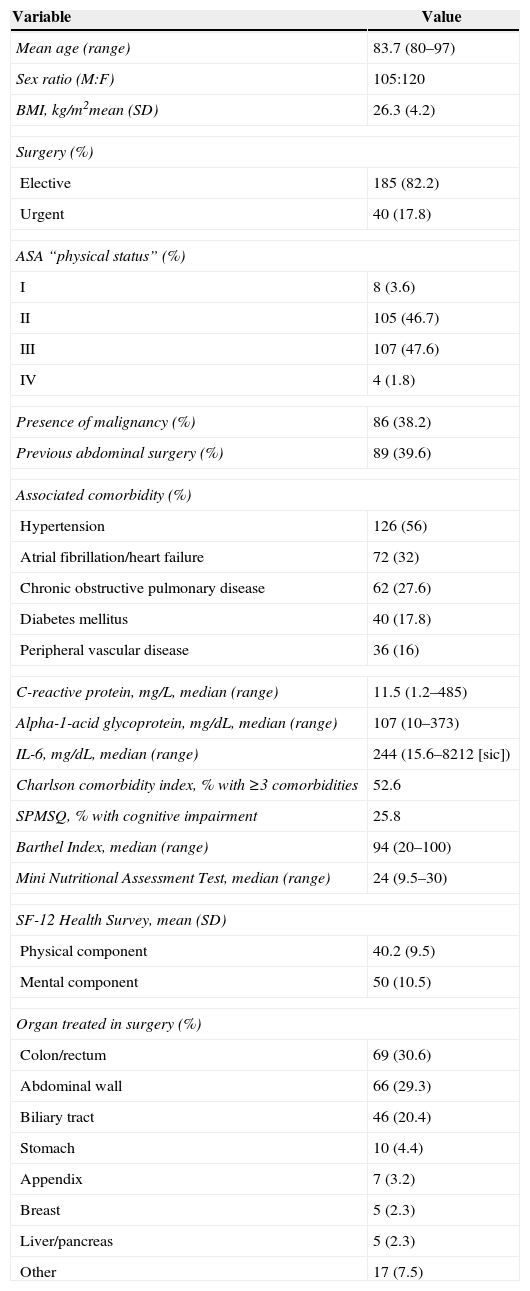

ResultsThe study population included 225 patients, 105 men and 120 women, with a mean age of 83.7 years (80–97). The characteristics of the sample, preoperative data and surgical site are shown in Table 1. Most patients were ASA II (46.7%) or III (47.6%). Urgent surgery was required by 17.8% of patients. A total of 86 patients (38.2%) had malignancies. High blood pressure (56%), heart diseases (32%) and pulmonary diseases (27%) were the most frequent concomitant diseases.

Characteristics of the Sample, Preoperative Data and Surgical Site.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean age (range) | 83.7 (80–97) |

| Sex ratio (M:F) | 105:120 |

| BMI, kg/m2mean (SD) | 26.3 (4.2) |

| Surgery (%) | |

| Elective | 185 (82.2) |

| Urgent | 40 (17.8) |

| ASA “physical status” (%) | |

| I | 8 (3.6) |

| II | 105 (46.7) |

| III | 107 (47.6) |

| IV | 4 (1.8) |

| Presence of malignancy (%) | 86 (38.2) |

| Previous abdominal surgery (%) | 89 (39.6) |

| Associated comorbidity (%) | |

| Hypertension | 126 (56) |

| Atrial fibrillation/heart failure | 72 (32) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 62 (27.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40 (17.8) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 36 (16) |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L, median (range) | 11.5 (1.2–485) |

| Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein, mg/dL, median (range) | 107 (10–373) |

| IL-6, mg/dL, median (range) | 244 (15.6–8212 [sic]) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, % with ≥3 comorbidities | 52.6 |

| SPMSQ, % with cognitive impairment | 25.8 |

| Barthel Index, median (range) | 94 (20–100) |

| Mini Nutritional Assessment Test, median (range) | 24 (9.5–30) |

| SF-12 Health Survey, mean (SD) | |

| Physical component | 40.2 (9.5) |

| Mental component | 50 (10.5) |

| Organ treated in surgery (%) | |

| Colon/rectum | 69 (30.6) |

| Abdominal wall | 66 (29.3) |

| Biliary tract | 46 (20.4) |

| Stomach | 10 (4.4) |

| Appendix | 7 (3.2) |

| Breast | 5 (2.3) |

| Liver/pancreas | 5 (2.3) |

| Other | 17 (7.5) |

Indications for surgery included colorectal disease in 30.6% of patients, repair of the abdominal wall in 29.3%, biliary disorders in 20.4% and gastric lesions in 4.4%. Acute appendicitis, breast tumours, and diseases of the liver and pancreas were less frequent.

In summary, colorectal disease, abdominal wall disease and biliary disease accounted for 80% of surgeries.

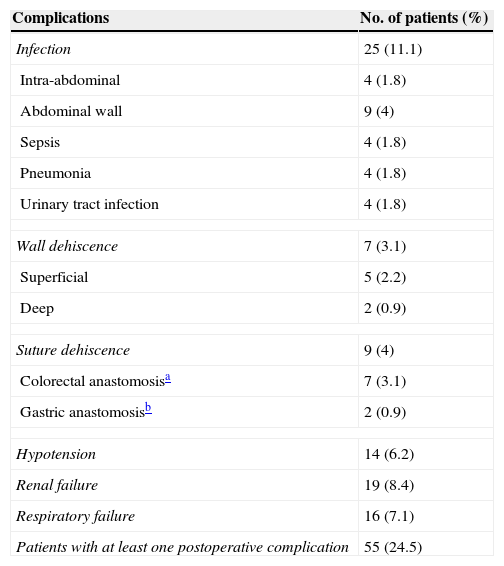

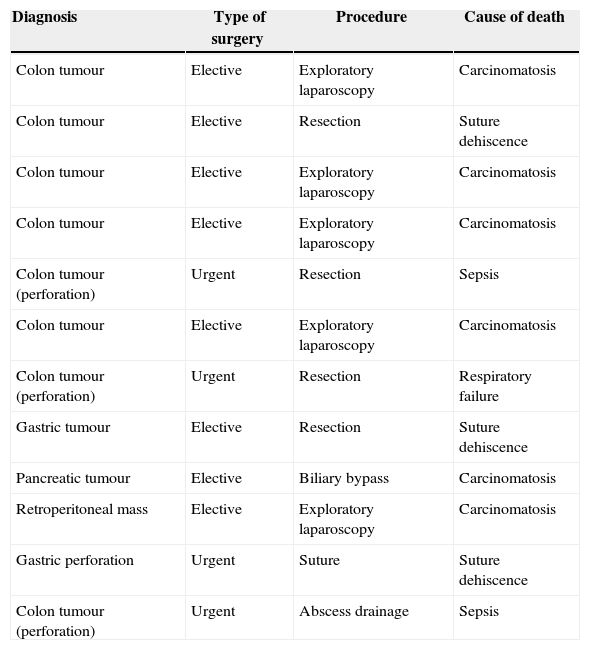

Postoperative complications occurred in 55 patients (24.4%); 25 of these patients met criteria for severe complications (11%). Wound infection was the most common complication (Table 2). Fifteen patients (6.6%) required reoperation. A total of 12 patients (5.3%) died (Table 3). Four of these patients had undergone urgent surgery, and the remaining eight, elective surgery. All the patients who died, except for one patient with peritonitis after gastric perforation, suffered from a malignant disease. Eight of the patients who underwent surgery due to colon cancer died (11.8%).

Postoperative Complications.

| Complications | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Infection | 25 (11.1) |

| Intra-abdominal | 4 (1.8) |

| Abdominal wall | 9 (4) |

| Sepsis | 4 (1.8) |

| Pneumonia | 4 (1.8) |

| Urinary tract infection | 4 (1.8) |

| Wall dehiscence | 7 (3.1) |

| Superficial | 5 (2.2) |

| Deep | 2 (0.9) |

| Suture dehiscence | 9 (4) |

| Colorectal anastomosisa | 7 (3.1) |

| Gastric anastomosisb | 2 (0.9) |

| Hypotension | 14 (6.2) |

| Renal failure | 19 (8.4) |

| Respiratory failure | 16 (7.1) |

| Patients with at least one postoperative complication | 55 (24.5) |

Causes of Death (12 Patients).

| Diagnosis | Type of surgery | Procedure | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colon tumour | Elective | Exploratory laparoscopy | Carcinomatosis |

| Colon tumour | Elective | Resection | Suture dehiscence |

| Colon tumour | Elective | Exploratory laparoscopy | Carcinomatosis |

| Colon tumour | Elective | Exploratory laparoscopy | Carcinomatosis |

| Colon tumour (perforation) | Urgent | Resection | Sepsis |

| Colon tumour | Elective | Exploratory laparoscopy | Carcinomatosis |

| Colon tumour (perforation) | Urgent | Resection | Respiratory failure |

| Gastric tumour | Elective | Resection | Suture dehiscence |

| Pancreatic tumour | Elective | Biliary bypass | Carcinomatosis |

| Retroperitoneal mass | Elective | Exploratory laparoscopy | Carcinomatosis |

| Gastric perforation | Urgent | Suture | Suture dehiscence |

| Colon tumour (perforation) | Urgent | Abscess drainage | Sepsis |

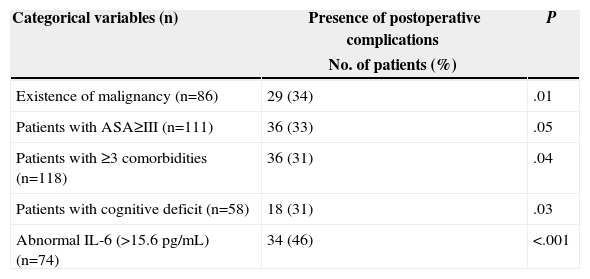

Table 4 shows the variables that presented statistically significant differences among patients with and without postoperative complications. Significantly higher complication values were observed in patients with malignancies, Charlson index with ≥3 comorbidities, ASA≥III or with cognitive impairment. In addition, serum levels of inflammatory biomarkers (AGP, CRP, IL-6) were significantly higher in the group with complications. Differences were also found with respect to leucocyte count, total protein, albumin, prealbumin, transferrin, bicarbonate, prothrombin time, creatinine, blood urea, and sodium.

Variables that Show Statistically Significant Differences (P<.05) With Respect to the Presence of Any Type of Postoperative Complication.

| Categorical variables (n) | Presence of postoperative complications | P |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients (%) | ||

| Existence of malignancy (n=86) | 29 (34) | .01 |

| Patients with ASA≥III (n=111) | 36 (33) | .05 |

| Patients with ≥3 comorbidities (n=118) | 36 (31) | .04 |

| Patients with cognitive deficit (n=58) | 18 (31) | .03 |

| Abnormal IL-6 (>15.6pg/mL) (n=74) | 34 (46) | <.001 |

| Continuous variables | Postoperative complications | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present (n=55) | Absent (n=170) | ||

| Heart rate, bpm, median (range) | 90 (50–130) | 80 (44–150) | <.001 |

| Leukocytes, cells/mm3 median (range) | 7880 (2900–27,950) | 6700 (2700–32,000) | .005 |

| Lymphocytes, cells/mm3 median (range) | 1310 (530–7900) | 1582 (480–5881) | .03 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, median (range) | 1.21 (0.34–5.7) | 1.06 (0.5–2.7) | .04 |

| BUN, mg/dL, median (range) | 0.59 (0.22–104) | 0.46 (0.13–99) | .03 |

| Sodium, mEq/L, median (range) | 139 (129–148) | 141 (122–147) | .001 |

| Prothrombin time, %, median (range) | 86 (22–100) | 94.5 (13–103) | .001 |

| Bicarbonate, mmol/L, mean (SD) | 24.6 (5.0) | 26.9 (3.5) | .003 |

| Total protein, g/L, mean (SD) | 63.5 (9.3) | 66.9 (7.2) | .006 |

| Albumin, g/L, mean (SD) | 34.1 (6.9) | 38.1 (5.8) | <.001 |

| Prealbumin, g/L, mean (SD) | 16.3 (6.7) | 20.1 (7.2) | .002 |

| Transferrin, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 202.4 (58.4) | 224.9 (51.3) | .01 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L, median (range) | 28.1 (3–485) | 6.2 (1.2–387) | <.001 |

| Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein, mg/dL, median (range) | 134 (60–373) | 99 (10–262) | <.001 |

When studying patients who had suffered serious complications (Clavien–Dindo grade III or IV), no differences were observed with respect to the overall group, and the same variables as in the overall group showed significance; these variables have already been detailed in Table 4.

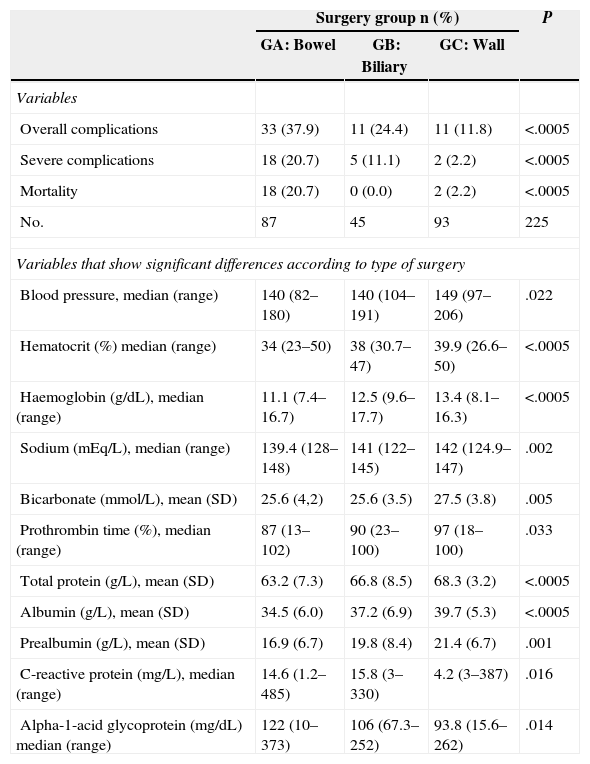

On the other hand, if the complexity of the surgery performed is taken into account (GA, GB and GC), significant differences among the three groups were observed regarding the percentage of complications suffered. The highest level of total complications, serious complications and mortality was observed in the bowel surgery group. Variables differed significantly and homogeneously among the three groups (Table 5).

Postoperative Complication Rate by Type of Surgery.

| Surgery group n (%) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA: Bowel | GB: Biliary | GC: Wall | ||

| Variables | ||||

| Overall complications | 33 (37.9) | 11 (24.4) | 11 (11.8) | <.0005 |

| Severe complications | 18 (20.7) | 5 (11.1) | 2 (2.2) | <.0005 |

| Mortality | 18 (20.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.2) | <.0005 |

| No. | 87 | 45 | 93 | 225 |

| Variables that show significant differences according to type of surgery | ||||

| Blood pressure, median (range) | 140 (82–180) | 140 (104–191) | 149 (97–206) | .022 |

| Hematocrit (%) median (range) | 34 (23–50) | 38 (30.7–47) | 39.9 (26.6–50) | <.0005 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL), median (range) | 11.1 (7.4–16.7) | 12.5 (9.6–17.7) | 13.4 (8.1–16.3) | <.0005 |

| Sodium (mEq/L), median (range) | 139.4 (128–148) | 141 (122–145) | 142 (124.9–147) | .002 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L), mean (SD) | 25.6 (4,2) | 25.6 (3.5) | 27.5 (3.8) | .005 |

| Prothrombin time (%), median (range) | 87 (13–102) | 90 (23–100) | 97 (18–100) | .033 |

| Total protein (g/L), mean (SD) | 63.2 (7.3) | 66.8 (8.5) | 68.3 (3.2) | <.0005 |

| Albumin (g/L), mean (SD) | 34.5 (6.0) | 37.2 (6.9) | 39.7 (5.3) | <.0005 |

| Prealbumin (g/L), mean (SD) | 16.9 (6.7) | 19.8 (8.4) | 21.4 (6.7) | .001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L), median (range) | 14.6 (1.2–485) | 15.8 (3–330) | 4.2 (3–387) | .016 |

| Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein (mg/dL) median (range) | 122 (10–373) | 106 (67.3–252) | 93.8 (15.6–262) | .014 |

The study was repeated after excluding the patients who underwent urgent surgery. Thus, 185 patients undergoing elective surgery were included in the analysis (82.2%), in whom the existence of severe complications was assessed. Again, the variables that showed statistically significant differences were the same as those observed in the overall sample (Table 4). Among the inflammatory markers, only IL-6 loses its significance (P=.079), although the percentage of patients with values above average was much higher in the group with complications.

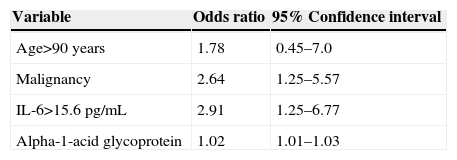

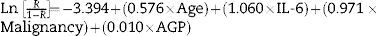

After the multivariate analysis, the development of the logistic regression model confirmed that only the levels of IL-6, AGP and the existence of malignancy were associated in an independent manner with the existence of morbidity (Table 6).

The equation used to calculate the risk (R) of postoperative morbidity adjusted by age is as follows:

where age is categorised as ≤90 years old=0, >90 years old=1; IL-6 is categorised as ≤15.6pg/mL (normal limit)=0, >15.6pg/mL (elevated value)=1; lack of malignancy=0, malignancy present=1 and AGP expressed in mg/dL.A non-significant result was obtained in the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (χ2=2.313; P=.97), which indicated correct calibration of the model, with a 22.2% sensitivity, 94.8% specificity, and a percentage of correct classification of 78.3%. The area under the curve (ROC) was 0.781 (95% CI: 0.703–0.858) (Fig. 1).

DiscussionFrailty in the elderly is associated with increased baseline inflammatory activity, which influences the physiological status of individuals by reducing their ability to withstand various forms of physical stress.14 Frail people are more vulnerable to the effects of surgery and therefore more prone to postoperative morbidity and mortality. How to quantify the level of frailty that may be relevant to the clinical practice is not well defined yet.10 Due to the fact that a growing number of older patients will be treated with surgery, an increase in overall perioperative morbidity and mortality rates should be expected. As a result of this, there is renewed interest in identifying factors associated with postoperative adverse outcomes in geriatric surgical patients.2–6

Regarding this point, it is well established that the presence of comorbidities associated with older age favours the occurrence of postoperative complications29 and there is consensus on the fact that nutritional status should be normalised before surgery in order to prevent serious postoperative complications.30

As already mentioned in the introduction, ageing is associated with increased serum levels of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and acute-phase proteins. A wide range of factors seem to contribute to this increase, leading to a persistently elevated inflammatory baseline status. It has also been shown that some inflammatory mediators are strong predictors of mortality, apart from other risk factors, in cohort studies conducted in elderly people.11–13

In our study we have performed a comprehensive review of the different variables that can influence the occurrence of postoperative morbidity in patients aged 80 and over treated with surgery. Close attention has been paid to the assessment of inflammatory markers (AGP, IL-6),31 which are not universally recognised as surgical risk markers by the medical community.

As shown in our series, the presence of malignancies and, in particular, colon cancer, often leads to surgery in elderly patients.2 In this study, 11 out of the 12 patients who died were operated due to an intra-abdominal malignancy, colon adenocarcinoma being the most common primary diagnosis.

When comparing patients with and without postoperative complications, beyond the differences observed in many other physiological and laboratory variables, it is worth noting the profile of inflammatory markers. According to our data, both patients with any type of complication and those who only had serious postoperative complications showed significantly higher preoperative serum levels of CRP, IL-6 and AGP than patients with no complications. When we compare together the three groups determined by the surgical complexity level (GA, GB and GC), we see that these biomarkers are also significantly higher in the group that will have more complications after surgery.

It is important to highlight that this same pattern is repeated when analysing only patients undergoing elective surgery, after eliminating the potential biases associated with inflammatory processes that are typical of urgent surgery.

We should stress the consistency with which the same variables are associated with the existence of complications, whether urgent surgery is included or not, and whether overall complications or just serious ones are considered.

The fact that after conducting the multivariate analysis, the only variables independently associated with morbidity are inflammatory markers (AGP, IL-6) and the existence of neoplasia should be underlined.

First of all, it is worth emphasising that the presence of neoplasia obviously implies a series of immunological and nutritional alterations that lead us to expect that it will be part of the equation.

However, the appearance of inflammatory markers as independent variables associated with postoperative morbidity supports the hypothesis that elderly patients with alterations in these markers undergo subclinical processes that weaken their health status and contribute to alter the postoperative course. Therefore, we think that these inflammatory markers could be used as objective markers of frailty.

In the same line of the data obtained in our study, Harris et al.11 showed an increased risk of death associated with elevated levels of IL-6 protein and CRP in a sample based on a population of healthy elderly people. Moreover, in a study of 1020 participants aged 65 and over living in the Chianti area of Italy,32 high levels of IL-6, CRP and IL-1RA were significantly associated with poor physical performance and decreased muscle strength.

On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that AGP is useful to assess mortality risk in elderly patients admitted to geriatric care centres.13

Focusing on the risk equation obtained, it should be remembered that it has low sensitivity (22.2%), but high specificity (94.8%). That is to say, some high-risk patients may not be detected, but there is a high probability of identifying low-risk patients correctly. On the other hand, the percentage of correct classification reaches 78%. The POSSUM risk assessment equation is recognised as one of the main surgical risk prediction systems used worldwide, so we will take it as a benchmark for our data. In the first article published in 1991, the POSSUM equation for the calculation of the morbidity risk showed a sensitivity of 52% with a specificity of 92% and a percentage of correct classification of 84%.24 It should be remembered that in order to gather data, the analysis focused on patients undergoing different types of surgical procedures and with very different degrees of expected morbidity, as we have done in our study. This is required in order to obtain a formula that can be applied globally.

Lack of model validation is the major limiting factor in our study.

However, as far as we know, the potential clinical significance of AGP and IL-6 has not been previously reported in this context. In fact, these findings reinforce the usefulness of AGP and IL-6 in the assessment of preoperative risks in geriatric surgical patients and, in our opinion, this is the clinically significant contribution of the study.

Additionally, we believe that these results reopen the debate about whether preoperative therapies with anti-inflammatory drugs could, in the future, improve the postoperative prognosis in elderly patients with altered levels of inflammatory markers before surgery.33

FundingThis study was partially funded by a grant from the Fundació Assaig for Health Research.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: González-Martínez S, Olona Tabueña N, Martín Baranera M, Martí-Saurí I, Moll JL, Morales García MÁ, et al. Proteínas mediadoras de la respuesta inflamatoria como predictores de resultados adversos postoperatorios en pacientes quirúrgicos octogenarios: estudio prospectivo observacional. Cir Esp. 2015;93:166–173.