Actinomyces infection is a chronic inflammatory process that can sometimes, clinically and radiographically, closely mimic a malignant tumour, which may lead to giving a delayed or inappropriate treatment.

Clinical caseMale 41 years old, with no previous history, with abdominal pain of one month onset, as well as weight loss, intermittent fever and diarrhoea. He developed acute abdomen and underwent surgery, finding a tumour in the distal ileum with necrosis and punctiform perforations. A resection was performed on the affected part of the ileum and colon, as well as an ileostomy using Hartmann's procedure.

ConclusionsActinomycosis is a disease that must be considered by the surgeon when faced with a clinical picture of subacute onset with intermittent fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, and even anaemia in patients with abdominal and retroperitoneal abscesses or previous history of surgery.

La infección por Actinomyces es un proceso inflamatorio crónico, que en ocasiones puede simular estrechamente un tumour maligno, tanto clínica como radiográficamente, lo que implica otorgar un tratamiento tardío o inapropiado.

Caso clínicoVarón de 41 años de edad, sin antecedentes previos. Presenta dolor abdominal de un mes de evolución, así como pérdida de peso, fiebre intermitente y diarrea. Desarrolla abdomen agudo y es intervenido quirúrgicamente, encontrando como hallazgos tumoración en el íleon distal, con áreas de aspecto necrótico, y 2 perforaciones puntiformes; se realizó resección de la parte del íleon y del colon afectadas e ileostomía, con procedimiento de Hartmann.

ConclusionesLa actinomicosis es una enfermedad que debe ser considerada por el cirujano ante un cuadro subagudo de evolución con fiebre intermitente, pérdida de peso, dolor abdominal e incluso anaemia, en pacientes con abscesos retroperitoneales y abdominales o antecedentes previos de cirugía.

Actinomyces infection is a chronic inflammatory process that can sometimes clinically and radiographically closely mimic a malignant tumour, which may lead to giving a delayed or inappropriate treatment. These lesions are called inflammatory pseudotumours and in most cases initial stimulus for their development remains unidentified. In some cases they may be mesenchymal processes with genuinely malignant cells. In the minority of case the causative agent is effectively identified.1

The Actinomyces species is a family of microorganisms which since their discovery have proved a challenge to physicians and researchers. This is a group of gram positive bacilli which are facultative anaerobic or strict anaerobic and which, in turn, divide into different species: Actinomyces israelii is the most common in humans. In the case of disease, over 50% of cases are orofacial or cervicofacial, with presentation in the abdomen being very rare (20% of all cases).2

This microorganism destroys the nearby vascularised tissues and replaces it with poorly irrigated granulation tissue, which leads to its anaerobic reproduction.

There are no radiographic data, laboratory tests or specific endoscopic imagining of the disease and the isolation of the organism is also fairly difficult, meaning that final diagnosis is often based on identification of the typical sulphur like granules in abscess material.3

Clinical caseMale patient 41 years of age with no history of diabetes or hypertension, who had smoked 1 cigarette a day since the age of 20 and drunk alcohol since the age of 18 and had been in a drunken state 3 times per week, with no prior history of surgery.

He presented at the emergency services one month prior to hospital admittance with diffuse abdominal pain, weight loss of 15kg, with no changes in eating habits. He also presented with loose stools, with no mucus or blood, fever only on 3 occasions during that month, and had been treated by a private doctor with trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole for 14 days. However, the patient decided to take the drugs for another 14 days. A general rash presented, and due to this he stopped taking the antibiotic and presented at the emergency department, owing to the persistence of symptoms.

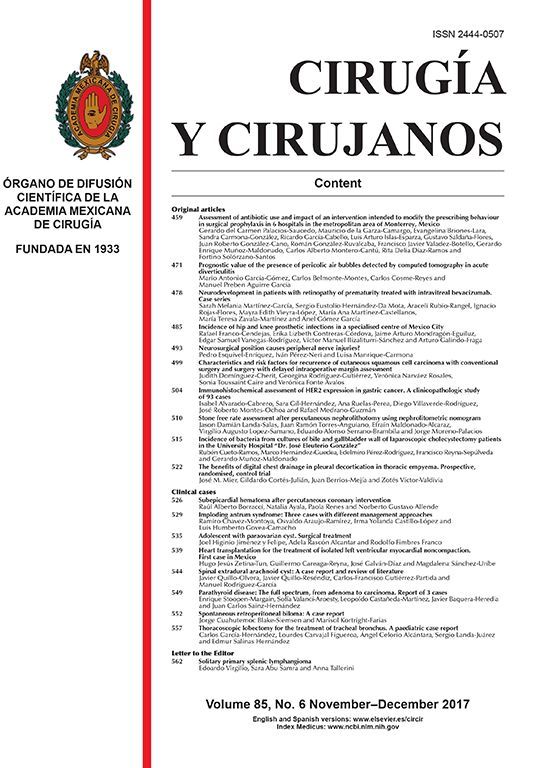

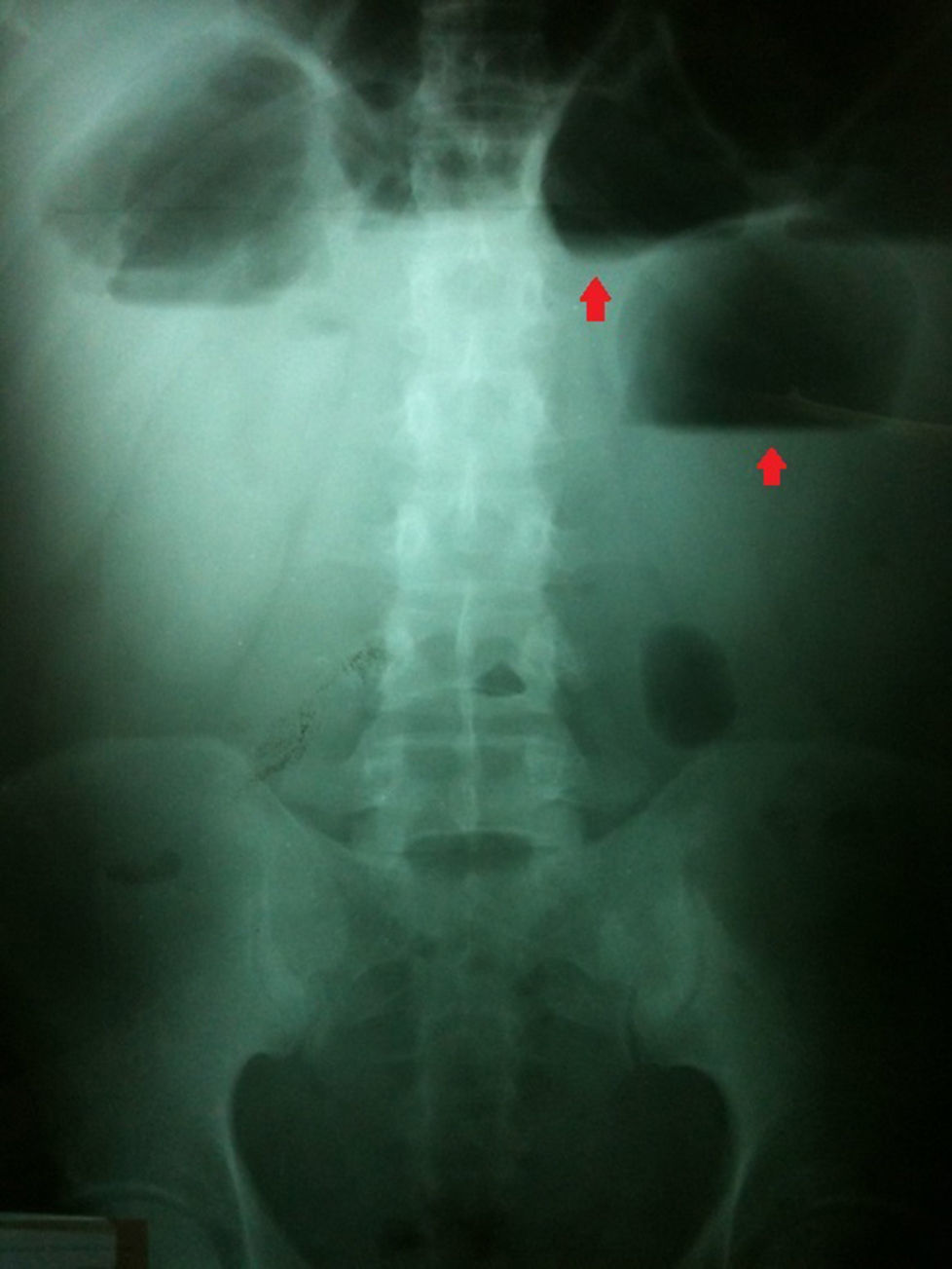

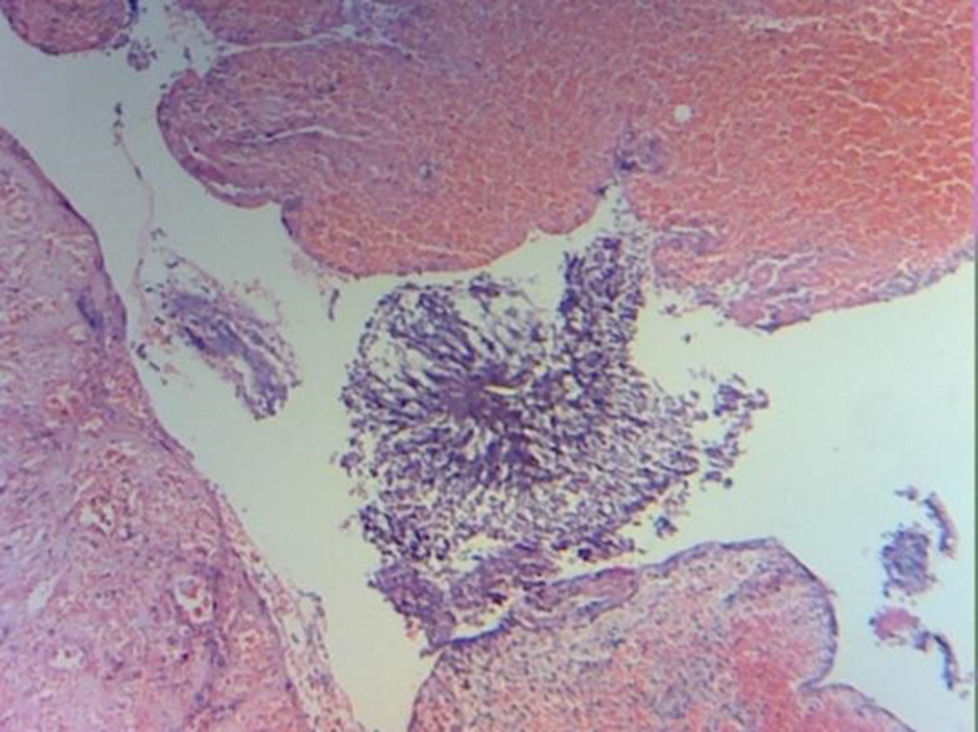

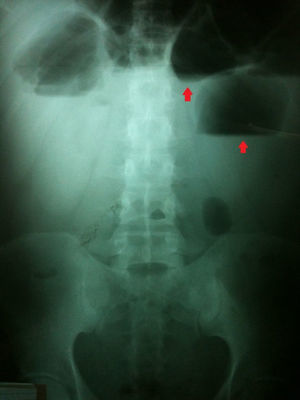

On hospital admittance he presented with stable vital signs, general paleness, abdomen with serious swelling, slight pain in the mesogastrium and right iliac fosse, with no peritoneal irritation. He was admitted to continue study protocol and after 48h presented with general malaise, fever of 38°C, rapid heartbeat, the inability to channel gases, and diffuse abdominal pain which gradually increased in intensity. Clinical symptoms were severe abdominal pain, 38°C temperature, leukocytosis of 19,500, with 16% band count. An X-ray of the abdomen showed hydro-aerial levels and ground-glass imaging (Fig. 1). Plain tomography of the abdomen was requested as well, which showed the inflammatory process involved the ascending colon, the distal ileum and the abdominal wall (Fig. 2).

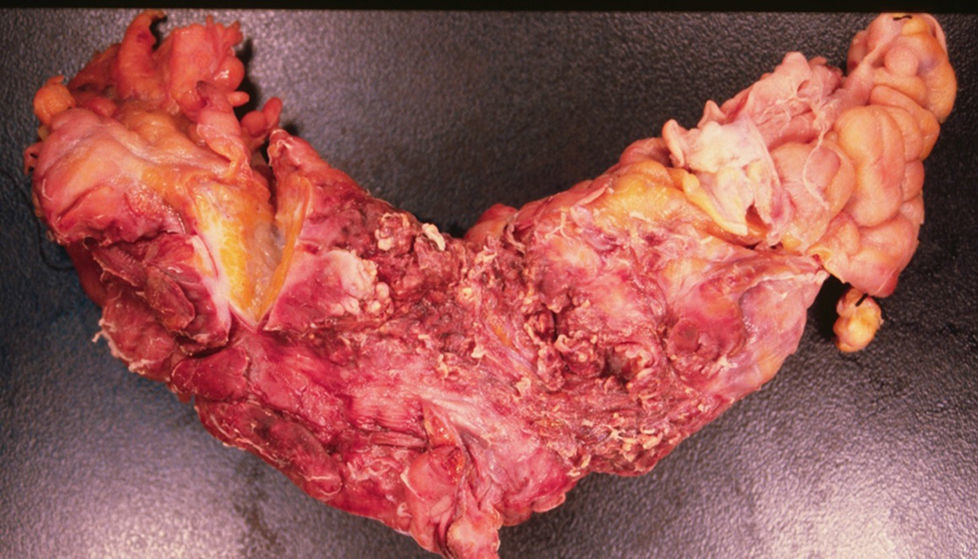

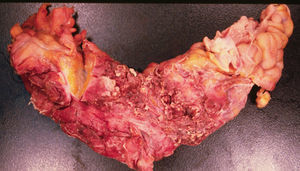

We decided to perform an emergency laparotomy, with transoperative findings of seropurulent testing liquid, multiple firm attachments which compromised the distal ileum and the ascending colon, the segment of distal ileum with whitish tumoral appearance, with areas which were necrotic in appearance, of firm consistency (Fig. 3) attached to the anterior wall of the abdomen and 2 pinpoint perforations. The Hartmann procedure was used to resect the affected part of the ileum and colon.

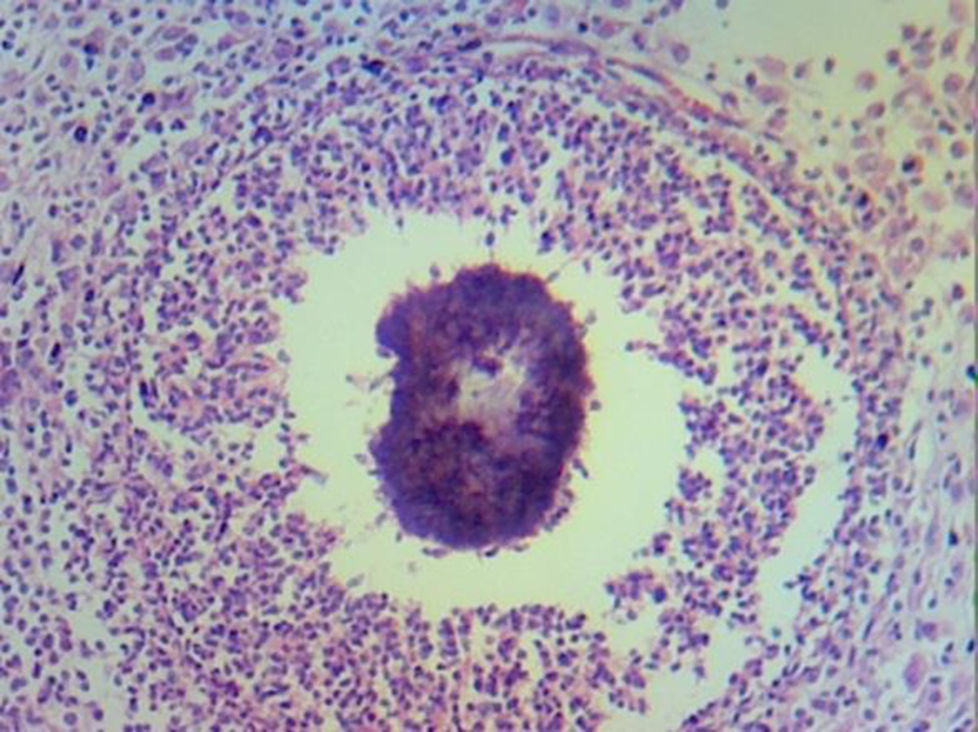

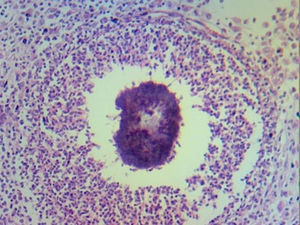

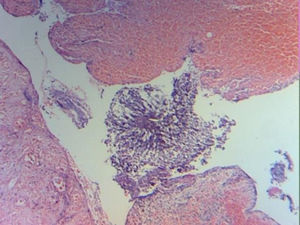

Laboratory tests reported chronic and acute peritonitis, with giant cell reaction, sulphur granulomas and the presence of actinomyces (Figs. 4 and 5). Antibiotic therapy was initiated based on intravenous clindamycin, which was subsequently continued when the patient was discharged from hospital. Evolution was satisfactory and the patient was discharged 5 days after surgery.

Patient followed up continued for one year, during which period the intestinal tract was reinstated and during which the patient continued to take clindamycin at a dose of 300mg orally every 8h. Once this period had terminated the patient was asymptomatic, with no complications and continued to be attended for check-ups by the general surgical outpatient service.

DiscussionActinomycosis is a disease which is rarely seen in a modern hospital environment. In one medical literature review by Cintron et al.4 the incidence of actinomycosis was estimated to be one in every 119,000 and one in every 400,000 cases per year.

Most incidences are reported in middle aged people. It is less frequently seen in people under 10 or over 60. Abdominal infection caused by Actinomyces in children is rare. In one review of English references only 12 cases of children with abdominal actinomycosis were identified.5

Actinomycosis generally mimics subacute infections or malignant tumours and radiologic diagnosis of this entity may be difficult. The involvement of the abdomen only occurs in 20% of cases of actinomycosis, and is for the most part confused with malignant processes, tuberculosis and inflammatory intestinal disease.6 Crohn's disease may also be included in the differential diagnosis due to the presence of severe weight loss, increase in erythrocyte sedimentation rate, severe anaemia, abdominal tumour and fever.7

This disease is commonly associated with the use of the IUD in women. The majority of reports describe that genital actinomycosis is associated with rectal stenosis, secondary to the presence of an IUD in a chronic state.8

It is as of yet unclear why Actinomyces change from commensal to pathogenic, just as the predisposing factors for the infection are not completely known. It has been suggested that this may be the result of damage to the mucous membrane or the interruption of tissues after surgery or trauma. Another etiological possibility could be immunosuppresion, but there is little evidence to support this as the main cause of actinomycosis. Reports in medical references exist on patients with diabetes and those taking steroids as the main factors of risk in developing the disease and it has been highlighted that actinomycosis usually presents in immunocompetent patients.9

All forms of actinomycosis may occur in HIV positive patients and in the presence of severe immunosuppression more invasive and malignant forms develop. Actinomycosis has also been reported in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, and the hereditary disease of the NADPH oxidase phagocyte system has also been described as a possible risk factor for actinomycosis, which suggests a possible role of phagocytes in the development of the disease.10

Correct diagnosis in the case of actinomycosis depends on 2 staining methods (haematoxylin-eosin), and due to the fact it is difficult to distinguish granulations immunofluorescence is also used.11 Some of the actinomycetes form conglomerations of 1–2mm in vivo called “sulphur granules”. These granules are almost patognomonic but their absence does not exclude the diagnosis of actinomycosis.12

Surgical treatment without antibiotics is not always sufficient to cure actinomycosis. When antibiotic therapy is combined with surgery curation is above 90%, treatment of choice is based on penicillin, tetracycline, erithomycin or clindamycin in patients who are allergic to penicillin.13

Although actinomycosis of the colon has been reported on previous occasions, very few cases have been reported where it is presented as the cause of intestinal obstruction and perforation.9

Radiological studies have not been particularly useful in preoperative diagnosis. However, although findings were nonspecific, tomography seems to be the most useful method of diagnosis, showing an infiltrating, non homogeneous mass, which may be used to guide a percutaneous biopsy and abscess drainage.14

Important characteristics suggestive of the disease in patient tomographies with intra-abdominal actinomycosis have also been reported and these characteristics include the presence of an adjacent tumour to the compromised intestine which may be concentric (83%) or eccentric. The tumour may be of cystic or solid material and in this case there was abundant granulated tissue and fibrosis which caused an increase in the contrast imaging.15

Menahem et al.16 reported their experience with the case of a 36 year old patient who had an IUD and who developed actinomycosis with gastric and colonic involvement. However, in our case the patient is one of the few cases reported in males and with no disease which could condition immunosuppresion, with the result that our hypothesis is that the disease was caused by a rupture of the mucous membrane unobserved in histological sectioning.

For their part, Choi et al.17 carried out a study describing clinical characteristics in 22 patients with abdominal actinomycosis, of whom only 2 were males, and similarly to our case they presented with symptoms mimicking cancer of the colon in patients without risk factors and without immunosuppression. This would support our theory of mucous membrane rupture in our patient caused by a previous inflammatory process.

Since actinomycosis may be effectively treated with penicillin and another group of antibiotics, conservative treatment seems viable. Surgical treatment may thus be avoided if diagnosis is carried out at the right time and appropriately, which appears to be possible with the aid of a colonoscopy, where the presence of abnormal nodules were reported, confirming the diagnosis by biopsy and medical treatment being possible.18

A sub-acute clinical presentation is frequent with progressive weakness, weight loss and chronic low grade fever often preceding focal symptoms such as abdominal pain, or a palpable tumour. In the long term therapy with antibiotics in combination with surgery is necessary to guarantee the complete eradication of the disease.19

ConclusionsAlthough actinomycosis is an infrequent entity, it should be included in the differential diagnosis of abdominal disease with inflammatory characteristic tumours, and should be particularly suspected when tomography shows the appearance of images of solid tumours with non homogeneous focal areas, and that tend to invade tissues and neighbouring structures. In this case in particular the rupture of the mucous membrane and the chronic alcoholism of the patient as the only conditioning factors of immunosuppression, could have triggered the infectious process. It is also interesting that the patient was a male, and in the cases reported in medical references on abdominal actinomycosis the majority are women, due to chronic use of the IUD. Actinomycosis is a disease which should be considered by the surgeon with sub-acute symptoms of evolution with intermittent fever, weight loss, abdominal pain or even anaemia in patients with retroperitoneal and abdominal abscesses, or a previous surgical history.

Please cite this article as: García-Zúñiga B, Jiménez-Pastrana MT. Abdomen agudo por actinomicosis con afección colónica: reporte de un caso. Cirugía y Cirujanos. 2016;84:240–244.