AZ31 magnesium alloy is one of the lightweight metallic engineering materials that are widely used in many industrial areas such as aviation, space, automobile and electronics industries, biomedical applications, where structural weight reduction is at the forefront of design principles. This study focuses on the growth of MgO and MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped oxide coatings on the surface of AZ31 magnesium alloy by micro arc oxidation (MAO) method in order to improve its usage areas and lifetime in industrial applications, and to investigate the structural, morphological, adhesion and corrosion properties of the grown coatings. In the study, MgO coatings were grown by MAO method and MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite oxide coatings were grown by adding sodium pentaborate (B5H10NaO13) nanoparticles into the electrolytic solution in MAO method. The phase structure of the grown coatings was determined by X-ray Diffraction (XRD), microstructure by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and chemical composition by Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS). The hardness of MgO and MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite oxide coatings were determined by microhardness tester, the adhesion resistance with the base material was determined by Scratch Tester and the corrosion resistance was determined by potentiodynamic polarization tester. As a result, it was observed that dense and homogeneous coatings were grown on the surfaces of particle-added (MgO:B5H10NaO13) coatings, that porosity and pore sizes on the surfaces of the coatings were reduced, that microcracks were reduced, and that coatings with high bond strength with the base material were grown. It was also determined that the corrosion resistance of the coatings with particle addition (MgO:B5H10NaO13) was higher than the corrosion resistance of the coatings without particle addition (MgO).

La aleación de magnesio AZ31 es uno de los materiales metálicos ligeros de ingeniería que se han utilizado ampliamente en diversas áreas industriales, tales como la aviación, el espacio, la industria automotriz y electrónica, así como en aplicaciones biomédicas, donde la reducción del peso estructural es un principio fundamental en el diseño. Este estudio se centra en el crecimiento de recubrimientos de óxido de magnesio (MgO) y recubrimientos de óxido compuestos dopados con MgO:B5H10NaO13 sobre la superficie de la aleación de magnesio AZ31 mediante el método de Microoxidación por Arco (MAO), con el fin de mejorar sus áreas de uso y la vida útil en aplicaciones industriales, así como para investigar las propiedades estructurales, morfológicas, de adhesión y de corrosión de los recubrimientos obtenidos. En el estudio, se crecieron recubrimientos de MgO mediante el método MAO y recubrimientos compuestos de óxido dopados con MgO:B5H10NaO13 mediante la adición de nanopartículas de pentaborato de sodio (B5H10NaO13) en la solución electrolítica durante el proceso MAO. La estructura de fases de los recubrimientos obtenidos se determinó mediante Difracción de Rayos X (DRX), la microestructura mediante Microscopía Electrónica de Barrido (MEB) y la composición química mediante Espectroscopía de Energía Dispersiva de Rayos X (EDS). La dureza de los recubrimientos de MgO y de los recubrimientos compuestos dopados con MgO:B5H10NaO13 se determinó con un microdurómetro, la resistencia a la adhesión con el material base se evaluó mediante un probador de rayado (Scratch Tester) y la resistencia a la corrosión se midió mediante polarización potenciodinámica. Como resultado, se observó que sobre las superficies de los recubrimientos con adición de partículas (MgO:B5H10NaO13) se formaron recubrimientos densos y homogéneos; además, se redujeron la porosidad y el tamaño de los poros en las superficies de los recubrimientos, se disminuyeron las microgrietas y se obtuvieron recubrimientos con alta resistencia de unión al material base. También se determinó que la resistencia a la corrosión de los recubrimientos con adición de partículas (MgO:B5H10NaO13) fue superior a la resistencia a la corrosión de los recubrimientos sin adición de partículas (MgO).

Magnesium (Mg) is a metallic engineering material with low density (1.74g/cm3), high specific strength, high damping ability, specific stiffness, strong electromagnetic shielding ability, good thermal fatigue resistance, high processing performance, biocompatibility, biodegradability and non-toxicity [1–6]. Due to their light weight and these superior properties, Mg and its alloys are widely used in many industrial fields such as aviation, space, electronics and automobile industry, defence industry and biomedical applications where structural weight reduction is at the forefront of design innovations [7–9].

In order to increase the application areas of magnesium in modern industry, to provide the desired mechanical and tribological properties, to provide better corrosion resistance, it is widely produced by alloying method. For this reason, magnesium has multiple alloy systems. Among these alloy systems, Mg–Al–Zn alloys (AZxx) are frequently preferred in industrial applications due to their high wear and corrosion resistance [10,11]. Within the Mg–Al–Zn alloy system, AZ31 alloys, which have light weight, high strength-to-weight ratio, high thermal and electrical conductivity, good corrosion resistance and excellent biocompatibility, have recently been preferred in many industrial applications such as aerospace and automotive industries, especially in bioimplant applications [12–14].

In addition to these superior advantages of Mg and its alloys, the most important disadvantages of Mg and its alloys are low surface hardness, high friction coefficient and poor wear resistance depending on the conditions of use, and low corrosion resistance due to being one of the most electrochemically active materials (−2.372V vs. SHE) [15–18]. Especially in orthopedic bioimplant applications in the human body, which is considered one of the most active corrosive environments, it is not possible for Mg implants to remain stable until the wound and/or fracture in bone and tissue parts heals due to their low corrosion resistance [14,18]. Surface improvement methods are needed to overcome these disadvantages of Mg and its alloys and to improve their usage areas and lifetime in industrial applications [4,17,19–21]. Many surface treatment techniques such as chemical vapour deposition, physical vapour deposition, anodising, plasma oxidation, sol–gel and priming are applied to improve the surface properties of light metallic materials such as Mg [14,20–23].

Among these surface treatment techniques, micro arc oxidation (MAO) method (also known as Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation (PEO) method) is an environmentally friendly, simple and economical electrochemical coating method applied to improve the surface properties of Mg and its alloys, increase their wear and corrosion resistance, improve their properties such as biodegradability and biocompatibility [14,21,24]. With the MAO method, homogeneous, hard, dense ceramic coatings with good adhesion strength with the base material can be grown on the surface of Mg and its alloys. The grown ceramic coatings provide good wear and adhesion resistance, high corrosion resistance, thermal stability and dielectric properties to the base material [21,23,25–29]. The MAO method involves the application of high anodic voltage and current density to the electrode using AC or DC welding, resulting in the formation of intense micro-arcs that trigger the oxidation reaction on the metal surface. The surface oxide layer formed after the MAO process is typically porous, homogeneous, hard and thick. This is mainly due to the application of high voltage, which induces the electrical breakdown effect of the surface oxides. The electrical breakdown effect leads to melting and re-oxidation of the metal electrode surface. This leads to the growth of a porous and thick oxide layer perpendicular to the electrode surface [30–34]. In particular, MAO coatings grown by AC welding have less porosity, less microcracks and better adhesion strength than coatings grown by DC welding [35,36].

Although the coatings grown by MAO method have high wear and corrosion resistance, dissolution and degradation of the coating structure may occur in long-term use in aggressive environments. It is stated that this is due to the porous surface structure of the grown coatings due to the nature of the MAO method [37,38]. For this reason, there is a need to reduce the number and size of pores of the coatings grown on the surface of the base material, improve their mechanical properties, provide high wear and corrosion resistance, and provide the desired antibacterial properties. For this purpose, doped composite oxide coatings are grown by adding nanoparticles (ZnO, GO, Ag, Al2O3, TiO2, ZrO2, SiO2, Fe2O3, CeO2, MgO, Cu, Zn, Co, SiN, SiC, graphite, graphene, h-BN, B4C, B5H10NaO13 etc.) into the electrolytic solution in MAO method [4,14,37–40]. When the recent studies in the literature are examined, boron and boron doped materials, which have superior physical and mechanical properties such as low density, high impact and abrasion resistance, high thermal conductivity and damping capacity among the nanoparticles added into the electrolytic solution, have started to attract attention [41–44]. Among boron compounds, sodium pentaborate (B5H10NaO13), which has the ability to dissolve in water, is shown as a candidate new generation boron compound to be used as additional nanoparticles in the MAO method.

In this study, we focused on the growth of MgO and MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped oxide coatings on the surface of AZ31 alloy by MAO method and investigation of the structural, morphological, adhesion and corrosion properties of the grown coatings in lactated ringer solution (Table 1). In the first step of the study, MgO coatings were grown in electrolytic solution-1 by MAO method. In the second step, MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite oxide coatings were grown in electrolytic solution-2, which was formed by adding sodium pentaborate (B5H10NaO13) nanoparticles into electrolytic solution number 1 (Fig. 1). The phase structure of the grown coatings was determined by X-ray Diffraction (XRD), microstructure by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and chemical composition by Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS). The hardness of MgO and MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite oxide coatings was determined by microhardness tester, adhesion resistance with the base material was determined by Scratch Test and corrosion resistance was determined by potentiodynamic polarization tester.

AZ31 (wt%: Al 2.5–3.5; Zn 0.6–1.3; Mn 0.2–1; Ca 0.04; Si 0.1; Cu 0.5; and balanced Mg) magnesium alloy was selected as the base material. In order to connect the AZ31 base materials to the MAO system, their edges were drilled with a diameter of 3mm and their surfaces were cleaned with SiC abrasives with grain sizes of 600, 800, 1000 and 1200 respectively and reduced to a roughness value of Ra≈0.15–0.35μm. Surface roughness measurements of the base materials were performed with a Mahr surface profilometer. The samples with the desired surface roughness values were rinsed with deionized water, cleaned with isopropyl alcohol and air dried at room temperature.

Growth of composite oxide coatings; In the MAO system schematically shown in Fig. 1, electrolytic solution-1 (Experiment 1) containing KOH (1.5g/L), Na2HPO4 (2g/L), Na2SiO3 (3g/L) and NaAlO2 (3g/L), The other one was carried out in electrolytic solution-2 (Experiment-2) obtained by adding sodium pentaborate (B5H10NaO13) (6g/L) nanoparticles into solution-1 (stirred with a magnetic stirrer for about 60min to obtain a homogeneous mixture) using a bipolar mode alternating current (AC) power supply operating at 600Hz constant frequency, 20/−10% duty and 600/−100V for 15min. In all experiments, stainless steel bath walls were used as cathode and AZ31 alloy samples were used as anode. During the plating process, cooling water was passed through the stainless steel bath walls to ensure that the electrolytic solution temperature did not exceed 30°C. After the MAO process, the coated samples were washed with distilled water and dried.

Surface topography, thickness, cross-sectional images and elemental analysis of MgO (Experiment-1) and MgO:B5H10NaO13 (Experiment-2) doped composite oxide coatings grown on the surface of AZ31 base material after MAO treatment were determined by Quanta FEG 250 scanning electron microscope (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDXS) integrated in this device. The phase analyses of the coatings were carried out at room temperature, between 20° and 90°, at 0.1° step and 2°/min scanning speed in a Rigaku brand XRD device with Cu Kα radiation (λ=1.54060Å), and 10mA and 30kV energy was applied to the filament during the process. Verification of the XRD graphs was performed with the Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS) peak lists.

The microhardness measurements of the untreated AZ31 samples and the samples coated by the MAO method were carried out by determining the deformation marks formed on the sample surface by applying a load of 10mN to the 136° Vickers indenter in 10s with the Buehler micromet 2001 hardness tester.

The adhesion force between the base material and the MgO and MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite oxide coatings grown on the surface of AZ31 samples after MAO treatment was determined by CSM Revetest Scratch Instrument using a 200μm Rockwell-C diamond tip at a sliding speed of 10mm/min and a loading rate of 100N/min.

Corrosion tests of MgO and MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite oxide coatings grown on the surface of AZ31 base material after MAO treatment were carried out with a potentiodynamic polarization tester in lactated ringer solution (Table 1) produced by Polifarma Company. Polarization measurements were carried out according to the three electrode technique and silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode was used as reference electrode (Re), platinum wire was used as counter electrode (CE) and the test sample was used as working electrode (WE). Potentiodynamic polarization measurements were performed with a scan rate of 1mV per second in the potential range of −1000mV to 950mV after the samples were kept for 30min until they reached the open circuit potential.

Results and discussionsStructural and mechanical propertiesThe surface of the coatings grown with the MAO method consists of volcano-like structures formed by discharge channels in the center. The elements included in the electrolytic solution of the coating melt during the coating process and start to overflow outward through the discharge channels and cool down when they come into contact with the cold electrolyte. As a result, distinct boundaries separating the volcano-like structure are formed [31]. Nanoparticles added to the coating electrolyte solution are involved in the coating formation by entering both the discharge channels and the microcracks formed on the surface during the coating formation. The nanoparticles included in the coating structure reduce the number and/or size of pores formed on the surface and also prevent the formation of microcracks on the surface. In this way, the roughness of the coating changes significantly [4,45,46]. In addition, the addition of nanoparticles in the coating solution causes the voltage/current value to decrease during the MAO process. This allows a thicker and more homogeneous coating to be grown in the same period of time [4,47].

The surface roughness values of AZ31 base material before coating and MgO and MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped oxide coatings grown under Experiment-1 and Experiment-2 conditions are given in Table 2.

Table 2 shows that the surface roughness value of the coatings grown in Experiment-1 condition is the highest. Due to the nature of the MAO method, the formation of a porous ceramic surface with a rough and volcanic appearance as a result of micro discharges on the surface causes the surface roughness of the coatings obtained in the Experiment-1 condition to be at the highest value [31,32,48]. It is seen that the roughness value of the coatings grown in Experiment-2 condition is less than the coatings grown in Experiment-1 condition. This is due to the fact that B5H10NaO13 nanoparticles added to the electrolytic solution in the Experiment-2 condition enter into the pores exposed during coating formation and cause the diameter and number of pores to decrease [4,40].

Fig. 2 shows the scanning electron microscope (SEM) images and EDS analyses of the surface morphology of the coatings grown by MAO method. In the SEM images, it is seen that the coatings grown on the surface due to the nature of the MAO method have a structure containing pores with a rough and volcanic appearance. These pores formed on the surface are called micro discharge channels and provide the surface to have a rough structure. Micro melting within these micro discharge channels on the surface causes the formation of many volcano-like circular pores of different sizes [31,32,49]. The pores formed on the coating surface have a circular geometry due to the circular progression of the solidification trace exposed after the localized melting that occurs in the discharge channels during the coating process [50,51,34]. In addition, uniform and non-uniform pores are clearly visible on the coating surface.

Fig. 2a shows the surface images and EDS analysis of the (MgO) coating grown in Experiment-1 condition and Fig. 2b shows the surface images and EDS analysis of the (MgO:B5H10NaO13) coatings grown in Experiment-2 condition. When Fig. 2 is examined, it is observed that the surface of the coatings grown in the Experiment-2 condition (Fig. 2b) has a less rough structure, and the number of volcano-like formations of different sizes and circular pores are much less. This is due to the fact that the added B5H10NaO13 nanoparticles enter into the pores exposed during coating formation, causing the diameter and number of pores to decrease [4,45,52].

In the MAO method, nanoparticles added to the coating solution enter into the micro-discharge channels and are incorporated into the coating structure. As a result, the number and size of pores formed on the surface decreases, and accordingly, the coating surface becomes more smooth and homogeneous (Table 2 and Fig. 2b). This leads to an increase in wear and corrosion resistance [4,45,52]. When Fig. 2b is examined, according to the EDS analysis taken from the surface of MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped oxide coatings grown in Experiment-2 condition, Al, P, K, O, and Na elements,[52] originating from Na2SiO3, Na2HPO4, KOH and NaAlO2compounds added in the electrolytic solution of the coating and Boron (B) element originating from B5H10NaO13 compound were found. The presence of element B indicates that B5H10NaO13 nanoparticles added into the electrolytic solution in the MAO method are included in the coating structure by entering into the discharge channels. This indicates that MgO coatings grown on the surface of AZ31 base material were doped with B5H10NaO13 and MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite oxide coatings were grown.

Fig. 3 shows the cross-sectional images of the coatings grown by MAO method under Experiment-1 and Experiment-2 conditions. In the cross-sectional SEM images, it is seen that there is a difference between the thickness of the coating grown under Experiment-2 conditions and the thickness of the coating grown under Experiment-1 conditions. The thickness of the MgO coating shown in Fig. 3a is ≈29μm and the thickness of the MgO:B5H10NaO13 coating shown in Fig. 3b is ≈45μm. This is due to the fact that the B5H10NaO13 nanoparticles added into the electrolytic solution reduce the coating start voltage value and allow a thicker and homogeneous coating to be grown in the same time [4,45]. In the cross-sectional images shown in Fig. 3a and b, it is seen that the coatings grown under Experiment-1 and Experiment-2 conditions grow adhesively on the surface and almost no separation of the coatings is observed. This clearly shows the compatibility of the coating and the base material surface.

When the literature is examined, it is known that the basic phase formed in the coatings grown on the surface of magnesium alloys by MAO method is MgO [53–55]. According to the XRD results shown in Fig. 4, it is seen that MgO phases are formed on the surface of the coatings grown under both Experiment-1 and Experiment-2 conditions. In the coatings with B5H10NaO13 nanoparticle addition (Experiment-2), MgB2 phases were also observed in addition to the MgO phase. This situation is in parallel with the literature [56]. B5H10NaO13 added to the electrolytic solution in the MAO process dissociates into Na+(BxOy)- ions in the solution [57,58]. During the formation of the coating, the discharge temperature rising up to 800–3000K at the arc points provides the formation of micro melts on the surface and ensures the inclusion of B2O3 in the coating structure in the stable structure with a melting temperature of 450°C [31,59,60]. B2O3 included in the coating structure decreases the formation temperature of MgO, MgB2, and Mg2SiO4 crystals and accordingly, the coating thickness increases with the effect of rapid solidification.

The EDS analysis in Fig. 2a and XRD results in Fig. 3 clearly show that B5H10NaO13 nanoparticles dispersed in the electrolyte were successfully incorporated into the structure of MAO coatings.

Fig. 5 shows the hardness values of the coatings grown under Experiment-1 and Experiment-2 conditions and the uncoated AZ31 base material measured by the microhardness measuring device. Here, the hardness value of the uncoated base material is approximately 57±2 HV0.05, and the hardness values of the coatings obtained in Experiment-1 and Experiment-2 conditions are 338±14 HV0.05 and 598±9 HV0.05, respectively. With the addition of B5H10NaO13 nanoparticles, the highest hardness value (598±9 HV0.05) was reached in the coatings obtained in the Experiment-2 conditions due to the boron particles entering the coating structure by entering the micro discharge channels during coating formation. The addition of B5H10NaO13 nanoparticles reduces the number and/or size of the pores formed on the coating surface, affects the growth of a more homogeneous and thick structure on the surface, causes the crystal structure of the coating to shrink and accordingly increases the microhardness value [4,45,61]. In addition, the addition of B5H10NaO13 nanoparticles affects the coating to be in a harder structure by limiting the dislocation movements with plastic deformation hardening caused by heat loss during solidification occurring in the discharge channels at relatively lower temperatures (∼450°C) [61]. Boron particles included in the structure of the coating affect the increase in the thickness of the coating (Fig. 3b) as well as the increase in hardness. This situation is in parallel with the literature [61–63].

In addition, when the studies in the literature are examined, it is stated that the most important factors affecting the hardness of MAO coatings are the phase composition of the coating and the homogeneous structure of the coating with less pores, and it is emphasized that the hardness of the coating and the homogeneity of the coating are directly proportional [32,64,65]. MgO phases were detected in all coatings grown on AZ31 alloy and MgB2 and B2O3 phases were detected in coatings grown in Experiment-2 condition (Fig. 4). The fact that these phases are the main phases of MAO coatings shows that compactness is more dominant on hardness.

Corrosion behavior of substrates and coatingsThe corrosion resistance of AZ31 base material and coatings grown by MAO method was carried out by potentiodynamic polarization tester in lactated ringer solution (Table 1) and the potentiodynamic polarization curves of these samples are given in Fig. 6. These potentiodynamic polarization curves reveal the corrosion behavior of the materials and the effectiveness of the MAO coatings. It is seen in Fig. 6 that the corrosion potential of the coatings grown in Experiment-1 and Experiment-2 conditions shows a positive trend and the corrosion current density decreases compared to the AZ31 base material. This indicates that the corrosion resistance of the uncoated AZ31 base material is effectively increased by the MAO process. Nanoparticles, which enter the discharge channels during coating formation and are included in the coating structure, provide thicker and less porous coatings. Accordingly, a more homogeneous oxide layer is formed on the surface and higher resistance to corrosion is obtained [21,66–68]. As shown in Fig. 6, the addition of B5H10NaO13 nanoparticles into the coating electrolyte solution in the coatings grown in the Experiment-2 condition, increased the positive current density and decreased the corrosion current density during coating formation and shifted the corrosion potential in the positive direction. This means that the corrosion resistance of the coatings grown in the Experiment-2 condition increased significantly [69].

It is shown in Fig. 2 that the MAO coatings grown under Experiment-1 conditions are less homogeneous and have more number and size of pores. This situation clearly reveals that the surface of the coatings grown without particle addition is more irregular and has larger pores. This morphology of the coating surface reduces the protective properties of the coating and decreases the corrosion resistance. The number and size of the pores on the coating surface and the structure of the coating cause the corrosion agents in the working environment (such as Cl ions in lactated ringer's solution) to penetrate easily into the coating and accordingly, the corrosion mechanism progresses rapidly in these regions [69–72].

However, it is shown in Figs. 2 and 3 that the coating surface of the MAO coatings grown in the Experiment-2 condition has a more homogeneous structure, has a smaller number and size of pores, and a denser and thicker coating is grown. Nanoparticles added to the electrolytic solution in the experiment-2 condition affect the increase in the density and thickness of the coatings and the decrease in the number and size of the pores. Accordingly, it provides an increase in corrosion resistance and the mechanical strength and chemical stability of the coatings are also significantly improved [71,72].

When the MAO coatings are compared, it can be concluded that the addition of particles in the coatings grown in the Experiment-2 condition causes the coating current density to increase and improves the surface properties and structure of the coating. Coatings grown with nanoparticle addition have fewer number and size of porosity and higher density than coatings grown without nanoparticle addition (Fig. 3). This enables nanoparticle-added coatings to exhibit a more resistant state in corrosive environments. Such coatings make it difficult for corrosion agents (such as Cl ions in lactated ringer's solution) in the working environment to pass through the coating layer due to the fact that nanoparticles added to the electrolytic solution enter the micro discharge channels during coating formation and provide a homogeneous distribution by being included in the coating structure and reduce pores and microcracks. In addition, nanoparticles are included in the microstructure of the coating, increasing the hardness and wear resistance of the coating. Thus, the coating is effective in creating a more effective barrier against corrosion.

In general, the higher the corrosion current density and the lower the corrosion potential of the base material, the lower the corrosion resistance of the material [69,73,74]. It is seen that the corrosion resistance of AZ31 base material is lower than MAO coatings (Fig. 6). The cathodic regions of the polarization curves of the MAO coatings and AZ31 base material are similar due to the fact that the electrochemical reactions in these regions are controlled by oxygen in the electrolytic solution [74]. In general, B, Ni and Si are known to be elements that can easily react with oxygen to form an oxide film [74,75]. In B5H10NaO13 doped composite oxide coatings, the film layer that may form on the surface due to B elements prevents the corrosive ions (such as Cl) in the corrosive environment from covering the surface of the composite oxide coatings and prevents direct contact of the metal surface with the corrosive environment by acting as a barrier on the base material surface. This increases the corrosion resistance of the coatings. In addition, thanks to the B particles included in the coating structure with B5H10NaO13 additive, coatings with high hardness (Fig. 5) are obtained, which contributes to the long life and durability of the coating.

Corrosion potentials (Ecorr) and corrosion current density (Icorr) values for AZ31 base material and MAO coated samples (Fig. 6) are shown in Table 3.

Electrochemical parameters of the polarization curves of samples.

| Samples | Corrosion potential (Ecorr) (mV) | Current density (Icorr) (μA/cm2) | Anodic slope (βa) (mV) | Cathodic slope (βc) (mV) | Polarization resistance (Rp) (Ωcm2) | Corrosion rate (CR) (Acm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZ31 substrate | −1.632 | 664.883 | 345.345 | 345.345 | 0.112914603 | 15,192.576 |

| Experiment-1 | −1.514 | 19.712 | 159.849 | 220.12 | 2.042503152 | 450.419 |

| Experiment-2 | −1.277 | 2.074 | 363.837 | 363.837 | 38.1364513 | 47.391 |

Rp (polarization resistance) and CR (corrosion rate) were calculated by the Stern–Geary equation [76]. Here βa is the anodic Tafel slope and βc is the cathodic slope.

According to the results in Table 3, the lowest corrosion resistance and the highest corrosion rate were determined in AZ31 base material. The coatings grown in the Experiment-2 condition were found to offer higher corrosion resistance and lower corrosion rate compared to the coatings grown in the Experiment-1 condition. In Experiment-2 condition, Rp increased and CR decreased with the addition of B5H10NaO13 particles into the electrolytic solution. Therefore, the best corrosion resistance was obtained in the coatings grown in Experiment-2 condition.

It is seen in Table 3 that the corrosion potential of the coatings grown by MAO method in Experiment-1 and Experiment-2 conditions is higher than the uncoated AZ31 base material. This shows that the corrosion resistance of the AZ31 base material is significantly improved by the coatings grown by the MAO method. When the MAO coatings were compared among themselves, it was determined that the coatings grown in the Experiment-2 condition provided the best corrosion resistance due to the denser and less defective structure of the coating surface (Fig. 6 and Table 3).

As a result, the corrosive solution penetrating AZ31 magnesium alloy is inhibited by the MAO coating [66]. It was determined that the corrosion resistance of the coating grown in Experiment-2 condition was better than the coatings grown in Experiment-1 condition. This is due to the fact that the composite oxide coating grown in the Experiment-2 condition has a thicker and homogeneous structure, and the microcracks and pores on the surface are less (Figs. 2 and 3), which affects the high corrosion resistance of the coating. This situation is in parallel with the literature [31].

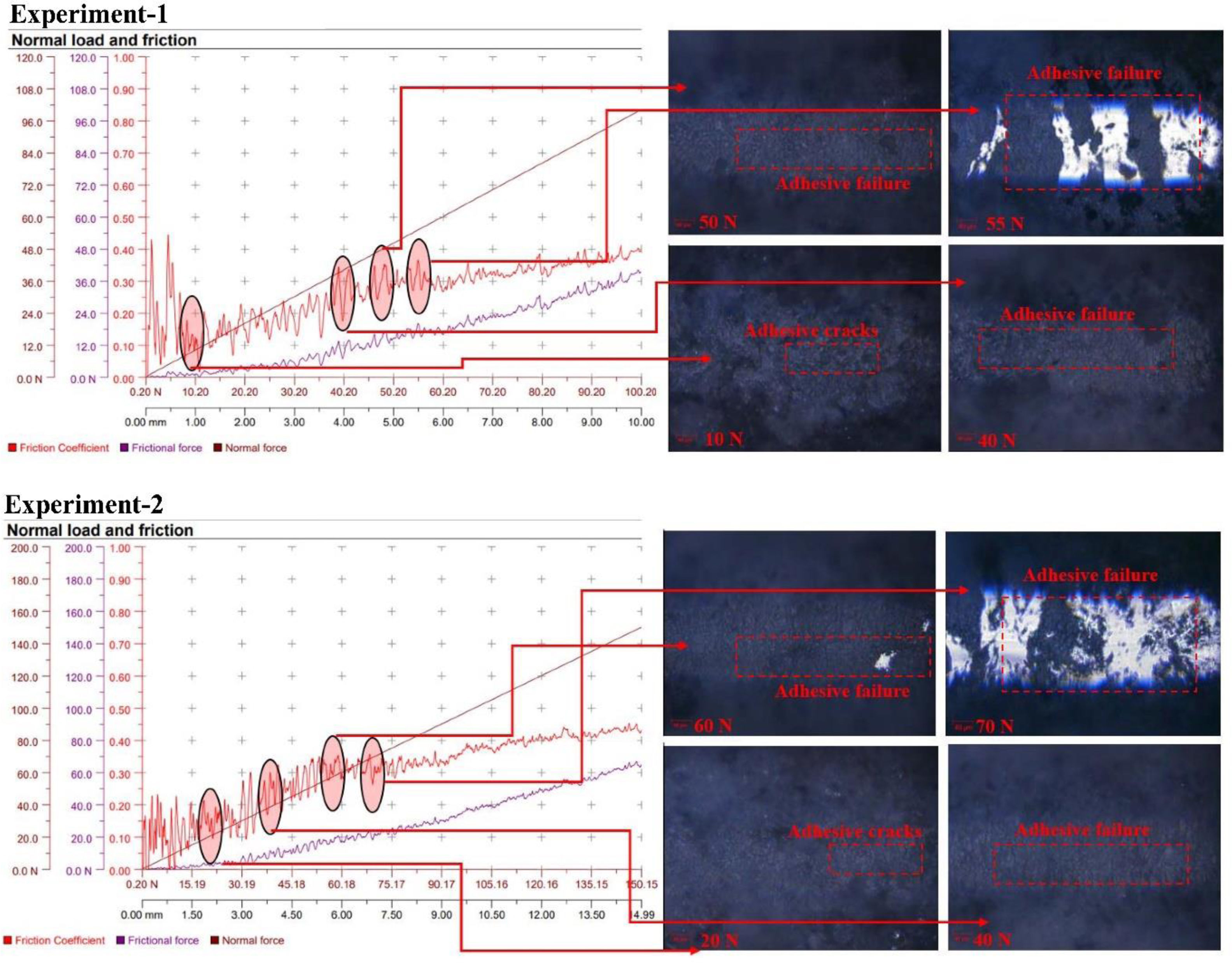

Adhesion behavior of MAO coatingsUnder the conditions specified in Table 2, the adhesion properties of the samples coated with the MAO coating method to the base material were examined in detail. The scratch test was used for this investigation and the results are presented graphically in Fig. 7. In the scratch test, a gradually increasing load (in the range of 0–100N) is applied on the coating and the reactions of the coating such as deformation, cracking and separation from the base are observed [77,78]. This method is a fundamental tool to understand the extent to which the coating adheres to the surface, its adhesion strength and mechanical strength [66,77,78].

The term “Lc” used in scratch testing refers to the “critical load” at which the coating begins to detach from the surface or shows mechanical damage below a certain load level and is considered an indicator of the adhesion strength of the coating. The critical load level is divided into three main categories. Lc1: This is defined as the load value at which the first microcracks or localized delaminations occur on the coating. Lc1 is the point at which the coating exceeds its elastic limit relative to the substrate and this load value tests the initial bond strength of the coating to the substrate. Lc2: This is the load level at which the bond between the coating and the base material is severely weakened and large cracks and structural fractures appear on the surface. At this stage, the coating shows a tendency for extensive and pronounced cracking at the surface and the risk of rupture increases significantly. Lc3: The critical load level at which the coating is completely detached from the surface or disconnected from the entire substrate. Lc3 refers to the level of complete detachment or peeling of the coating from the surface and is considered the load value at which the maximum mechanical limit of the coating is exceeded.

In this study, only Lc1 and Lc2 values were reached in the tested coatings and Lc3 value was not reached; i.e. the coatings showed partial cracking on the surface but did not completely detach from the surface. This indicates that the coatings have a high bond strength with the base material and can remain attached to the surface even after passing their initial elastic limit. These results also indicate that the improvement efforts to increase the durability and stability of the coatings were successful [77,78].

When the Lc1 values of the coatings were compared through the microscope images and the graphs obtained, it was found that the highest value was found in the composite coatings grown in the electrolyte medium containing B5H10NaO13 particles. This high Lc1 value reveals that B5H10NaO13 doped coatings provide a very strong adhesion to the base material. The presence of this additive increased the structural strength of the coating, resulting in a stronger bond with the substrate.

In both coating types, adhesive cracks were observed to form when a load level of approximately 30N was reached. As shown in Fig. 7, these cracks showed a more localized connection with the surface rather than spreading over the surface, indicating that the cracks formed in a controlled and homogeneous structure. Although the crack intensity and depth increased as the load increased, the coating did not completely detach from the surface, indicating that the coating provides an advantage in terms of resilience and strength.

This analysis allows a better understanding of the behavior of coatings under various load levels and contributes to optimizing coating compositions in surface modification studies. In particular, the effect of different particle contents on the adhesion strength of the coatings was clearly demonstrated and it was determined that coatings doped with B5H10NaO13 particles were effective in improving the surface adhesion performance.

When the microscope images of the coatings were examined in detail (Fig. 7), light and dark colored regions on the surface were clearly observed. In these images, the light colored regions represent the base material on the surface where the coating is applied, while the dark colored regions represent the applied MAO coating layer. This distinction offers the possibility to visually analyze how well the coating is bonded to the surface and the effectiveness of the applied coating process. Furthermore, the microscope images provide direct information on the quality of the adhesion between the coating and the base material, providing a critical resource for assessing the structural integrity and homogeneity of the surface.

In Experiment 1, an oxide layer grown in an electrolyte medium without B5H10NaO13 particles was used. During the scratch test on this coating, when the applied load reached 45N, a sudden change occurred on the surface. This abrupt change indicates that the structural integrity of the oxide layer on the surface is broken at this load level and that the coating can no longer adhere to the surface at loads above 45N. This critical load value represents the point at which the oxide layer deforms on the surface and the adhesion capacity to the base material is limited. The 45N load level represents a critical threshold where mechanical weaknesses such as deformation, crack formation and lateral shifts occur on the coating and is considered the maximum critical load. At this level, the coating starts to lose its ability to adhere to the surface, which is a factor that limits the long-term durability of the coating [66,79–81].

Coatings grown in electrolyte media containing B5H10NaO13 particles (Experiment-2) showed a different performance in the scratch test. In the tests performed on the samples of Experiment-2, the maximum critical load was determined as 100N, which is quite high compared to the coatings without particles. The critical load value of 100N indicates that the B5H10NaO13 particles act as a reinforcing phase in the coating layer and provide a stronger adhesion of the coating to the surface. The B5H10NaO13 particles increase the mechanical durability of the coating by forming a more durable structure on the surface and help the coating to remain bonded to the surface even at high loads. This shows that the particles have an increasing effect on the bonding force in the coating, which positively affects the scratch resistance and the strength of the coating under load [66,81].

When the surface scratch resistance of Experiment-1 and Experiment-2 coatings were compared, significant differences were observed in terms of the depth and width of the scratch mark. It was determined that the scratch mark was deeper and wider in the Experiment-1 coating than in the Experiment-2 coating. This deeper and wider scratch mark indicates that the mechanical strength of the particle-free coating is lower and provides a more limited adhesion to the base material. In contrast, the scratch mark is narrower and more superficial in the Experiment-2 coating, and no delamination (complete detachment of the coating from the surface) was observed on the coating up to the 90N load level. The Test-2 coating exhibited a more robust adhesion on the surface, maintaining adhesion quality even at high load levels.

These scratch test results clearly show that the Test-2 coating bonded much better to the surface and maintained its integrity with the surface even at high loads. In addition, the higher scratch resistance of the B5H10NaO13 doped coatings reveals that the presence of particles on the surface increases the mechanical durability of the coating and contributes to its wear resistance.

The results reveal that the scratch resistance of coatings is mainly determined by the phase composition, hardness degree and surface structure of the coating. B5H10NaO13 particles, which have a hard and durable structure, provide a stronger adhesion by increasing the hardness ratio of the coating, thus increasing the scratch and abrasion resistance of the coating. This reinforcing effect of the particles in the coating helps the coating to maintain its long-term durability and mechanical integrity on the surface [66,82].

It reveals the direct effect of the electrolyte medium and particle additives used in the coating processes on the adhesion strength and scratch resistance strength of the coating. In particular, the reinforcement effect of B5H10NaO13 particles in the coating stands out as an effective factor in improving the mechanical performance and longevity of coatings. The B5H10NaO13 doped coatings in Experiment-2 provided a strong adhesion to the base material and formed a surface structure with high mechanical durability. These results suggest that optimizing the additives used in coating applications can play an important role in improving surface performance and long-term durability.

ConclusionsThis research focused on determining the effect of sodium pentaborate (B5H10NaO13) nanoparticle addition to MgO coatings grown on AZ31 magnesium alloy using MAO method on the structural, morphological, corrosion and adhesion properties of the coating. The results obtained in the research are summarized below;

When MgO (Experiment-1) and MgO:B5H10NaO13 (Experiment-2) doped composite oxide coatings grown on the surface of AZ31 magnesium alloy by MAO method were compared, it was determined that the addition of B5H10NaO13 nanoparticles reduced the initial voltage value of the coating and enabled the growth of coatings with a thicker and homogeneous structure. The presence of element B was detected in the EDS analysis taken from the surface of MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite coatings and MgB2 phases were determined in XRD analysis. This indicates that the B5H10NaO13 particles added into the electrolytic solution penetrated into the coating and MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite coatings were successfully grown by adding B5H10NaO13 to the MgO coatings grown on the surface.

The highest hardness value of 598 HV was achieved in MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite coatings grown by MAO method. The reason for this is that the addition of B5H10NaO13 nanoparticles is included in the coating structure by entering in micro discharge channels during coating formation and accordingly, it is determined that the number and/or size of the pores formed on the coating surface decreases and a more homogeneous structure is formed on the surface. It was determined that the B particles included in the coating structure increased the hardness of the coating

When the corrosion tests were evaluated; it was observed that the corrosion potential of all coated samples was higher than the uncoated AZ31 base material. This shows that the oxide layer grown on the surface of the base material by MAO method effectively increases the corrosion resistance. MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite coatings were found to have the best corrosion resistance among the MAO coatings due to their more dense and homogeneous structure and fewer number and size of pores on the coating surface. This shows that the addition of nanoparticles into the electrolytic solution effectively increases the corrosion resistance of the coating.

When the scratch tests were evaluated; the highest Lc value was obtained in MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite coatings with 100N. This clearly shows that the MgO:B5H10NaO13 doped composite coating grown with nanoparticle addition is much better bonded to the base material and maintains its integrity with the surface even at high loads. It was determined that the particles added to the electrolytic solution act as a reinforcing phase in the coating layer, affecting the stronger bonding of the coating to the surface.

The author gratefully acknowledges Mr. Faruk Durukan and Kale Natural Corp. for their generous provision of sodium pentaborate used in this research.