α-Alumina was synthesized from recycled aluminum, which has shown reflective properties similar to a commercial version. The powder's characteristics were elucidated through X-ray diffraction (XRD) and UV–Vis spectroscopy, revealing its capacity to reflect up to 92.84% of visible radiation within the 400–800nm spectral range. This reflection efficiency is 0.32% lower compared to the high-purity commercial version. These characteristics enabled its application in the synthesis of reflective coatings on enameled low-carbon steel to produce diffuse reflectors (DR). The coatings were synthesized using the Sol-Gel method and applied via spraying. Subsequently, they underwent visible spectroscopy, hardness testing, and adhesion testing to evaluate their performance. These tests revealed that the coatings exhibited diffuse reflection (ρd) up to 72.30% of visible radiation, significantly enhancing photothermal generation by 10.33% and photovoltaic generation by 7.3% as determined by the computational simulation software Comsol Multiphysics. The coatings also demonstrated a hardness of 5H and an adhesion strength of 5B.

Se sintetizó α-alúmina, a partir de aluminio reciclado, la cual exhibió propiedades reflectivas similares a una versión comercial. Las características del polvo se determinaron mediante difracción de rayos X (DRX) y espectroscopia UV-Vis, revelando su capacidad para reflejar hasta el 92,84% de la radiación visible en el rango espectral de 400 a 800nm. Esta eficiencia de reflexión es un 0,32% inferior a la de la versión comercial de alta pureza. Estas características permitieron su aplicación en la síntesis de recubrimientos reflectantes sobre acero esmaltado de bajo carbono para producir reflectores difusos (DR). Los recubrimientos se sintetizaron mediante el método Sol-Gel y se aplicaron por pulverización. Posteriormente, se sometieron a espectroscopia visible, ensayos de dureza y ensayos de adhesión para evaluar su rendimiento. Estas pruebas revelaron que los recubrimientos exhibieron una reflexión difusa (ρd) de hasta el 72,30% de la radiación visible, lo que mejoró significativamente la generación fototérmica en un 110,33% y la generación fotovoltaica en un 7,3%, según lo determinado por el software de simulación computacional Comsol Multiphysics. Adicionalmente, también demostraron una dureza de 5H y una fuerza de adhesión de 5B.

In the pursuit of fulfilling global energy demands, humanity has discovered a valuable ally in the sun. Throughout history, this resource has been utilized for diverse activities, spanning both subsistence and commercial sectors. The advent of the industrial revolution and the emergence of novel technologies that catalyzed the development of new production methods marked a significant surge in energy demand. Consequently, alternatives such as coal and petroleum derivatives garnered substantial attention due to their cost-effectiveness and high energy density, albeit at the expense of substantial environmental degradation. In response to the energy crises resulting from the escalating costs of oil production and refining, research and development of technologies that harness solar radiation, whether in its light or thermal form, experienced a resurgence since the 1970s [1,2]. The continuous innovation in this technology has propelled their efficiency to remarkable heights, reaching efficiencies of 34%, 80.26%, and 47.1% in flat solar collectors, parabolic collectors and photovoltaic cells (in multi-junction) respectively, demonstrating their transformative potential [3–5]. Despite advancements and new developments, the primary disadvantage of these technologies remains environmental conditions. Which implies that, the direct utilization of solar radiation is contingent upon geographical location, weather patterns, and seasonal variations. Therefore, regions far from the equator, as well as areas with cloud cover or during autumn and winter, experience a reduction in the generation of photovoltaic and photothermal energy [6].

In 1966, Tabor [7] proposed the utilization of boost reflectors to enhance the incident solar radiation reaching the surfaces of solar systems (irradiance). The primary objective of this proposal was to augment the irradiance, thereby increasing the conversion performance of solar systems in proportion to the reflector's contribution. Since the dissemination of this proposal, numerous research endeavors have been conducted, resulting in the development of diverse reflective surfaces that aim to replicate or enhance the original proposal ranging from using polished metal surfaces, through the use of ceramic coatings, the use of composite materials, polymeric bases or the combination of two or more of these, which has allowed the classification of reflectors into five groups based on their primary manufacturing materials: reflective glass reflectors (borosilicates, silica, quartz, and lead alkali), polymeric reflectors (acrylic, polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), polyvinyl fluoride (PVDF), and polycarbonate), aluminum reflectors (anodized, rolled aluminum, and pure aluminum), stainless steel reflectors (austenitic, ferritic, martensitic, and polished), and multi-union reflectors [8–12].

Building on the ongoing development of this latest type of reflectors, Ortega González et al. [13] synthesized a diffuse reflector (DR) capable of reflecting between 78.31 and 74.70% of solar radiation generated by the Sol-Gel method. The primary reflective material of this DR was α-alumina, which exhibited a reflectance of 93.71% in powder form. Unlike parabolic and specular concentration reflectors, which aim to redirect the maximum amount of radiation onto a small surface area, a DR's objective is to cover the largest possible area of the solar system. This attribute holds significant importance in photovoltaic systems, where variations in irradiance can result in uneven generation across the cells within a panel [14–17].

Although aluminum and its derivatives have demonstrated promising reflective performance in the production of DR, not all nations possess the requisite natural resources for their manufacture. In Mexico's specific instance, according to data from the Mexican Mining Chamber (CAMIMEX) and the Mexican Geological Service (SGM), aluminum ranks 15th among metals produced domestically, placing it outside the top 20 globally. This primary limitation stems from the scarcity of bauxite, the primary resource utilized in its production. For this reason, the aluminum required for significant industries such as the automotive sector (∼40% of national consumption), construction (∼25%), and the food industry (∼20%, primarily in the production of cans) is imported from countries like the United States, Brazil, and Jamaica [18–20]. Hence, the recycling of this versatile metal holds immense significance for various applications, encompassing economic objectives such as cost reduction and environmental considerations such as waste reuse and diminished environmental impact of products and services.

Although can production is not the primary activity utilizing this metal, it is the most accessible for obtaining, collecting, and processing, which explains why collecting it in small quantities and informally has become a popular activity among the general population. This research concentrated on synthesizing alumina with a purity comparable to that of commercial alumina and employing it to manufacture a DR to enhance the generation of solar energy, both photovoltaic and photothermal, by utilizing waste and thereby mitigating the environmental impact of this renewable energy source. After all, it is estimated that by 2050 there will be between 60 and 78 million tons of photovoltaic panel waste worldwide, which not only implies the need to develop processes to eliminate them, but also a growing demand for raw materials for the construction of the next generation of photovoltaic panels. This demonstrates the urgent need to promote recycling not only of materials from solar technologies, but also the application of devices made from recycled materials that increase energy production from both current and future generation systems. This could additionally result in a reduction in raw material extraction, lower production costs, and the creation of new industries and jobs dedicated to resource recovery [21,22].

Experimental methodologySyntehesis of α-alumina from recycled aluminum cansSynthesisThe synthesis was adapted from the Bayer process and the methodology of Ibarra-Cruz et al. [23], using aluminum cans as the raw material. The can bodies were cut, milled, and sieved to obtain particles smaller than 1.2mm. For the alkaline digestion, 5g of aluminum scrap were added to 500mL of 2.5M NaOH under stirring (200rpm) for 24h at room temperature, yielding a translucent solution with brown precipitates. After filtration, the precipitate was discarded and the clear solution was neutralized with concentrated HCl to pH ∼7, producing a white gelatinous aluminum hydroxide. The precipitate was washed with hot distilled water until neutral conductivity, dried at 90°C for 24h, and finally calcined in air, leading to the transformation of Al(OH)3 into α-Al2O3, as confirmed by XRD A comprehensive description of the process is presented in Fig. 1.

CharacterizationDRXCrystallographic analysis of the synthesized and commercial alumina powder was conducted using an INEL Equinox 2000 diffractometer equipped with a kα1 cobalt source (λ=1.789010Å) and a curved detector. The obtained data were indexed using Crystal Impact Match software. Subsequently, the indexed data were compared to ascertain whether the synthesized alumina exhibited the identical characteristic peaks.

Analysis of crystallite sizeThe crystallite size of both the synthesized and commercial alumina was determined using the Scherrer equation (Eq. (1)).

where D is the crystal size, β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) and θ the angle was obtained directly from the angle 2θ obtained from the diffractogram in section 2.1.2.1. The FWHM was obtained by means of a Gaussian-Lorentzian fit of the XRD using Origin Pro software; to convert degrees (°) to radians, the values were multiplied by π/180.Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDXS)The sample underwent analysis using a Jeol IT 300 variable pressure scanning electron microscope. Spot analyses were conducted on scanned areas of approximately 4.5mm2 at magnifications of 100 and 2000× to assess morphology and identify agglomerations. If present, the shapes of these agglomerations were observed. Furthermore, an elemental chemical analysis was performed to identify compounds and residual impurities from the synthesis process that are not detectable via XRD. This characterization technique holds paramount importance in ascertaining its potential application within the realm of DR manufacturing.

UV–Vis spectroscopyThe reflectance of both commercial alumina (α-Al2O3 Sigma–Aldrich® CAS Number: 1344-28-1 at 98%) and the synthesized alumina was measured using an Ocean Optics UV-VIS USB3000 model spectrometer in a wavelength range of 400–800nm. The measurements were calibrated with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). The data obtained were integrated using the trapezoidal method in Origin Pro software.

Reflective coatingSynthesisThe ceramic coating was prepared following the sol–gel methodology described by Ortega-González et al. [13], with the only modification of replacing commercial α-Al2O3 with the recycled alumina obtained in this work. The suspension consisted of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), an acrylic adhesive (B-18 sealer), ethanol, deionized water, nitric acid (5%), α-Al2O3 powder, and white paint, mixed under constant stirring (1500rpm) at low temperature for 10min to obtain a homogeneous colloidal system.

Application by sprayingThe suspension was deposited onto SAE 1008 low-carbon steel substrates using a gravity-feed spray gun (1.4mm nozzle, 30psi, fan size ∼22cm, 600mL capacity). Spraying was carried out at room temperature with constant air pressure to ensure uniform deposition. The coated substrates were first dried at ambient conditions for 24h and subsequently heat-treated at 100°C for 1h to consolidate the coating.

CharacterizationUV–Vis spectroscopyThe reflective coating was characterized using the identical spectrophotometer employed for the alumina powder, and within the identical radiation spectrum. The acquired data was subsequently processed using Origin Pro software.

HardnessBased on the ASTM D3363 standard, the graphite pencil method was employed, utilizing a set of pencils with graphite tips varying in hardness. The test procedure involves sliding these pencils, commencing with the softest tip and ceasing once a scratch is generated on the surface by one of the tips [24].

AdherenceThe coating's hardness was determined using the ASTM D3359 standard. This standard involves generating six vertical parallel scratches and six perpendicular scratches on the coating. Subsequently, an adhesive tape specifically designed for this test is applied to the coating and removed. The percentage of coating loss is then calculated to determine the adhesion strength using the software ImageJ [25].

Measurement of irradianceTo ascertain the precise impact of the diffuse reflector, the incident radiation on a surface was quantified using a KIPP & ZONEN SP lite 2 pyranometer under ambient conditions at Mineral de la Reforma, Hidalgo, Mexico, on October 8, 2024.

SimulationFor the simulation of the effects on the generation of photovoltaic solar energy, the application of photovoltaic cells in the Comsol Multiphysics software was utilized, and previous research on the effects of radiation on the generation of photovoltaic systems was referenced [1,25–28]. The S01MC-100 model from the Solartec brand was considered, capable of producing 28.5V at open circuit (Voc) and 5A at short circuit (Isc), and a power output of 100W [29]. Three simulations were conducted using this data. The initial simulation was conducted under ideal AM 1.5 operating conditions. The second simulation considered the panel's operating temperature using the Nasrin equation [26]. The final simulation incorporated the additional radiation provided by the DR.

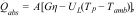

In the specific context of photothermal generation, considering the diverse configurations of flat-plate collectors and the varying number of piping, concentrations, capacities, and flow rates, an extensive and independent study is required. Thus, a specific simulation is not included. However, it was feasible to estimate the impact on these systems by considering two of the constitutive equations for the design of solar heaters (refer to Eq. (3) and 3). In these equations, the working temperature is directly proportional to the incident solar radiation (G), which increases proportionally to the capacity of the DR to redirect the irradiance [17,26,27,29–33].

where:Q⋅abs is the heat absorbed by the collector (W).

A is the collector area (m2).

η is the collector efficiency (≈0.7–0.9 for flat collectors and 0.6–0.8 in vacuum tubes).

UL is the thermal loss coefficient (≈4–6Wm−2K−1 for flat plate collectors and 0.5–2Wm−2K−1 for vacuum tubes).

Tp is an absorber temperature (K).

Tamb is an ambient temperature (K).

Techno-economic analysisTo assess the impact and economic feasibility of employing a diffuse reflector in solar systems, a technical analysis was conducted. This analysis enabled the prediction of the theoretical additional energy generation provided by this device over a one-year period. Additionally, it facilitated the calculation of the rate of return on investment required for its manufacturing per square meter.

For this purpose, the approximate cost of manufacture was considered, encompassing the proportional unit price of each reagent and the assumption that the average insolation in Mexico ranges between 5 and 6.36kWh/m2 per day. In view of this, Eq. (5) was utilized for this analysis.

where PB(Years) is the time needed to amortize the investment, CPDR is the approximate cost of manufacturing the DR and CAEP is the cost of solar energy generation, where the latter is the product of the average generation per day for 365 days a year and the percentage of reflectance, as shown in Eq. (6).where DI is the daily insolation received per square meter, AEP is the additional energy produced by the effect of the DR and η is the efficiency of the solar device.Results and analysisCharacterization of α-alumina powderFig. 2 shows the crystalline phases corresponding to α-alumina synthesized with identification sheet PDF-96-900-9784 [34] and PDF-96-100-0033 for the commercial case.

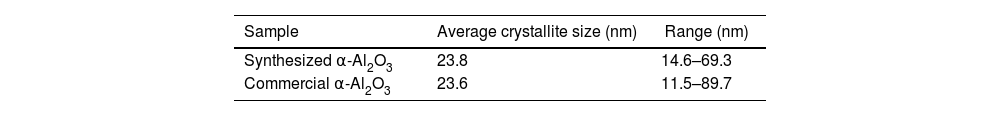

The crystallite size was estimated using the Scherrer equation as a first approximation. For the synthesized alumina, the average crystallite size calculated from the main diffraction peaks was ∼22nm, while the overall average from all indexed peaks was ∼24nm. In comparison, the commercial alumina showed average values of ∼19nm and ∼24nm, respectively (see Table 1). These small differences (2–3nm) are within the typical uncertainty of the method and should be considered indicative rather than precise.

A slight shift of approximately 0.5° in 2θ was observed in the synthesized sample. This can be associated with the formation of secondary silicon-containing phases during crystallization, as suggested in the literature [35]. This interpretation is consistent with the EDX analysis, where traces of Si (<1wt%) were detected (Fig. 5).

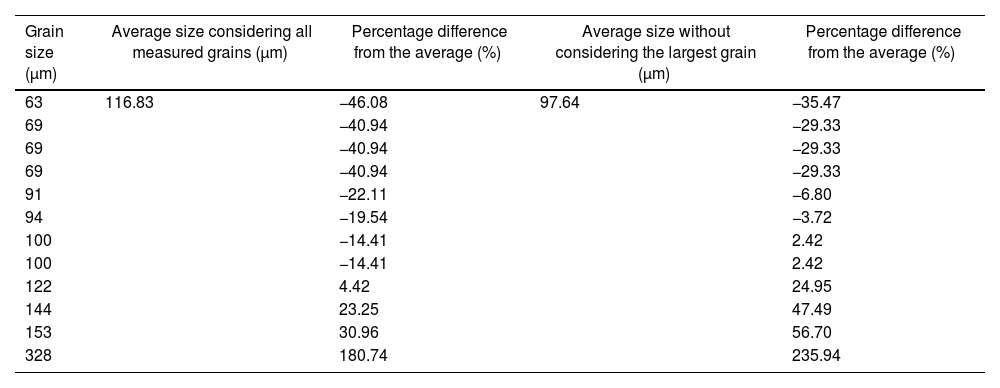

Fig. 3 shows the SEM micrograph at 100× magnification, where agglomerates with irregular morphology and sizes between ∼60 and 330μm are observed. The size of these agglomerates can be attributed to the almost metallic specular luster, as previously reported [36–39]. Although the largest agglomerates are visually prominent, most particles are smaller, with an average size of ∼100μm. This broad size distribution and irregular morphology can be advantageous for diffuse DR, since heterogeneity enhances light scattering in multiple directions, improving whiteness and diffuse reflectivity. Previous studies on hybrid microstructured coatings (e.g., TiO2 nanocomposites) have shown that disordered particle assemblies with wide size ranges suppress specular reflection and increase diffuse reflectance [40,41]. Such behavior favors more uniform radiation dispersion, minimizing local temperature gradients in photovoltaic systems.

A comprehensive analysis of the measured agglomerates sizes is presented in Table 2. The average size was calculated to be 116.83μm when considering the largest, which measures 328μm. However, recognizing the unique dimensions and scale of this, an alternative average can be derived by excluding it, resulting in a value of 97.64μm. Finally, the percentage variation of each with respect to each of the calculated averages is presented. When considering the largest agglomerate, the variation ranges from −40.94% to 180.74%. Conversely, when excluding the largest, the variation ranges from −29.33% to 56.70%.

Grain size at 100× of synthesized α-alumina.

| Grain size (μm) | Average size considering all measured grains (μm) | Percentage difference from the average (%) | Average size without considering the largest grain (μm) | Percentage difference from the average (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 63 | 116.83 | −46.08 | 97.64 | −35.47 |

| 69 | −40.94 | −29.33 | ||

| 69 | −40.94 | −29.33 | ||

| 69 | −40.94 | −29.33 | ||

| 91 | −22.11 | −6.80 | ||

| 94 | −19.54 | −3.72 | ||

| 100 | −14.41 | 2.42 | ||

| 100 | −14.41 | 2.42 | ||

| 122 | 4.42 | 24.95 | ||

| 144 | 23.25 | 47.49 | ||

| 153 | 30.96 | 56.70 | ||

| 328 | 180.74 | 235.94 |

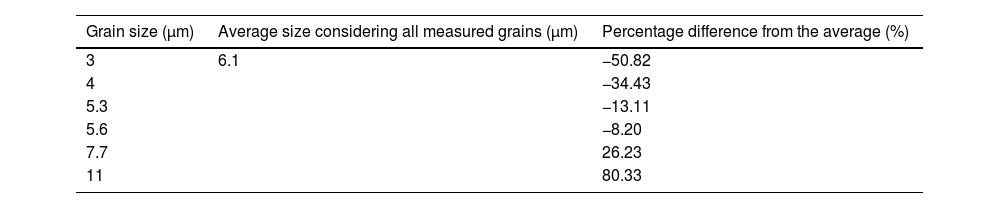

At higher magnification (2000×, Fig. 4), the microstructure reveals lamellar features of 3–11μm, consistent with the morphology of α-alumina obtained by conventional pressureless sintering [36]. Thus, the material exhibits a hierarchical structure composed of fine lamellae interspersed with larger agglomerates on the order of hundreds of micrometers, a morphology that enhances reflection in the visible and near-UV regions. These results highlight the importance of refining particle size control in future work to optimize optical performance. In the case of the 100x micrograph, the average size and the variation of measurements with respect to it were calculated, as presented in Table 3.

Fig. 5 presents the elemental composition of the sample. Besides Al and O, trace amounts of Si, Na, Ti, K, and Fe were detected, all with concentrations below 1wt.%. Due to the low sensitivity of EDS for light elements and the associated uncertainty, these values should be interpreted only as an indication of the presence of minor impurities rather than as precise quantification. Their presence is consistent with the original aluminum alloy [23] and with the fact that such species are not completely removed during washing or filtration steps. Although not detected by XRD, these trace elements may still play a structural and morphological role. For instance, Si incorporation could favor the local formation of mullite-like domains, potentially contributing to the slight 2θ shift observed in the diffractogram [42,43], while Fe substitution has been reported to distort the alumina lattice, generating microstrain effects [44–46]. Moreover, elements such as Si and Fe can segregate at grain boundaries, promoting secondary phase formation or inducing lattice distortions that hinder homogeneous grain growth. Similar effects have been reported in doped alumina systems with Mg, Y, and La, where grain boundary mobility is inhibited, leading to more irregular particle morphologies and a broader size distribution. This increased roughness and heterogeneity enhances light scattering at the surface, thereby favoring diffuse reflectance, as also evidenced in silica-doped alumina aerogels, where small amounts of dopants significantly increase scattering efficiency.

In Fig. 6, a comparative analysis of the reflectance of the synthesized compound and its commercial counterpart is presented. Based on the integration of the area under the curve, the commercial version exhibits a reflectance of 93.16%, while the one derived from recycled aluminum has a reflectance of 92.84%. This similarity in values, suggests that the material obtained is suitable for the production of diffuse reflectors. The decrease in reflectance can be attributed to amorphous impurities that were not completely removed during the filtration and washing processes, as well as unidentified amorphous phases and grains exceeding 5μm in size and the size of the largest crystallite.

Coating characterizationAs observed in Fig. 7, the reflectance ρd decreases when alumina is incorporated into the synthesis of the coating. In contrast, the commercial version can reach 75.88%, while the synthesized product obtained through recycling achieves 72.30%. This reduction of 3.58% suggests that the compound produced can compete with a commercial version in the manufacturing of DR. The decrease in reflectance primarily occurs at wavelengths exceeding 630nm. This phenomenon can be attributed to the formation of amorphous SiO2 compounds, which are generally transparent to near-infrared radiation (from approximately 700nm) and to this was attributed to the initial decrease in reflectance in the synthesized alumina. This observation is further supported by the fact that Si is an element present in the originally processed aluminum alloy and during the coating synthesis process and the addition of TEOS contributes to the formation of silicon polymers, in addition to the conditions of the alumina powder previously described, such as grain and crystallite size, as well as the presence of impurities [23].

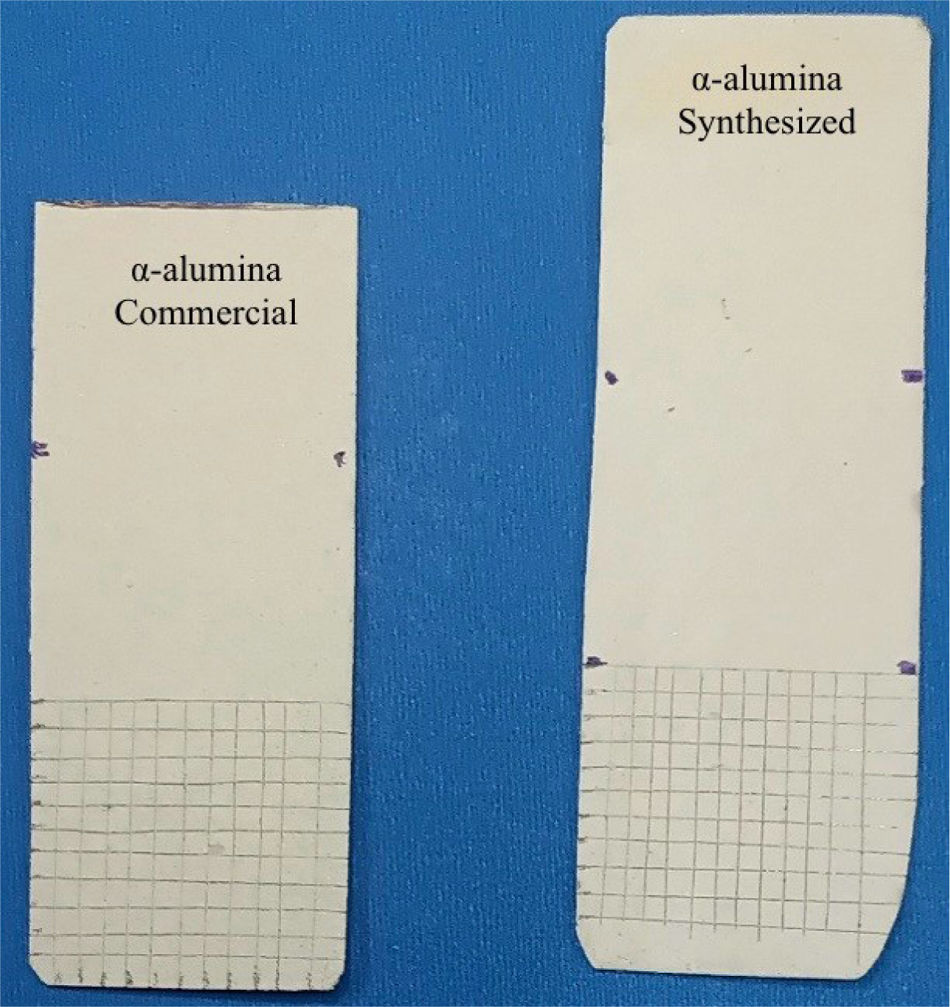

The hardness and adhesion values obtained after the tests were 5H and 5B for synthesized alumina (The highest achievable scores in this assessment. and 5H and 4B for commercial alumina. This indicates that both materials have the same hardness, and the coating manufactured from the synthesized alumina exhibits greater adhesion. This may be attributed to the larger grain size of the reflective material, which results in a greater contact surface between the substrate and the material. These findings demonstrate that the coating possesses the necessary characteristics for a coating designed to function under challenging conditions (Fig. 8).

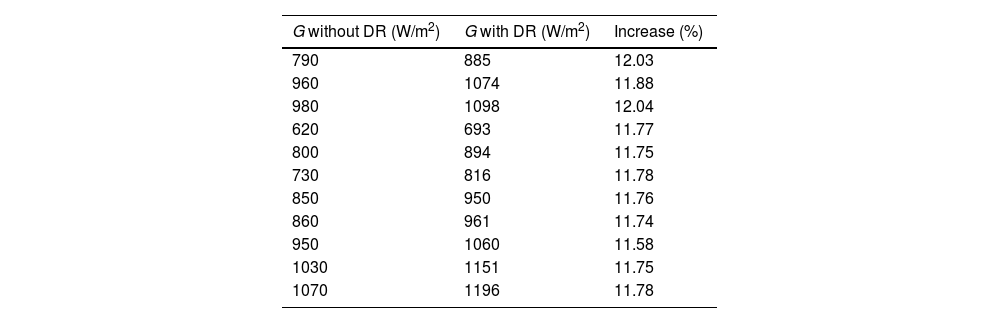

Meanwhile, Table 4 shows the values of the irradiance measurements carried out. The increase in incident radiation is between 11.58 and 12.04% with a mean of 11.81%. This variation in values may be due to different factors, such as cloudiness, the angle of inclination over the zenith, etc.

SimulationBy utilizing the data derived from the optical characterization of the reflector, it was feasible to replace the average value in the simulation of the photovoltaic panel. The outcomes are presented in Figs. 9 and 10, which juxtapose the panel's generation under ideal conditions (green), under actual operating conditions (yellow), and with the reflector developed in this research (blue). It is evident that electric current generation commensurately increased with the increase of incident solar radiation, resulting in a direct correlation between the intensity of the radiation and the photogeneration achieved by the photovoltaic panel. However, the voltage is decreased due to the concomitant rise in temperature induced by the increased incident radiation. However, the generated power of 97.3W is nearly comparable to the 100W that the panel could produce under ideal operating conditions, where the temperature is 25°C.

This advantage can be capitalized not only in high irradiance conditions, such as those prevalent in countries situated near the equator, but also to enhance the utilization of solar technologies in regions characterized by persistent cloud cover, limited sunlight hours, or low intensity.

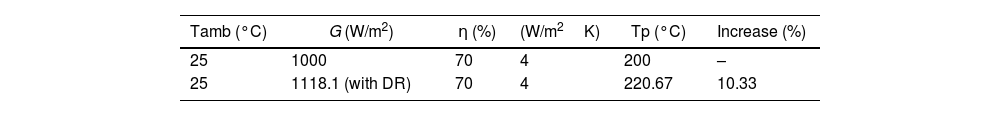

In reference to the performance of photothermal systems, Table 5 presents the enhancement in stagnation temperature for a 1m2 flat-plate collector. Initially, the stagnation temperature was 185°C, achievable at an irradiance of 1000W/m2. However, upon the introduction of the DR, the irradiance is increased to 1118.1W/m2, resulting in a subsequent stagnation temperature of 203.90°C. This temperature increase corresponds to a 10.33% rise.

Techno-economic analysisIt was estimated that the manufacturing cost considering all the necessary reagents without the steel substrate is approximately $ 109.38 MXN per m2, which is equivalent at the time of this work to $ 5.96 USD or € 5.05 EUR with commercial alumina and € 3.48 with synthesized alumina. While the theoretical additional generation produced under average sunlight conditions in Mexico by the reflector (using Eq. (6)) in a photovoltaic panel was estimated between 16.83 and 21.38kWh per year. For the specific case of the panel model used in the computational simulation of this work, the efficiency was not provided by the manufacturer, but was obtained through its dimensions, which are 1.445m×0.547m, so its area is 0.79m2 and given that the power generated under standard conditions is 100W; It was determined that a surface area of 1m2 would be possible to produce 126.56W, giving it an efficiency of 12.65%. However, it is well known that there are photovoltaic panels with higher efficiency than this value, reaching up to 26.7% in monocrystalline silicon cells [5], which means that the recovered power could be between 35.91 and 46.08kWh per year.

Considering this information and knowing that the base cost per kWh in Mexico in 2025 is $0.044 USD (∼€0.037) [47], the investment in the coating could be returned between 2.04 and 5.59 years. This will always depend on the conversion efficiency of the photovoltaic technology and the climatic conditions. It is well known that there are photovoltaic cells with higher efficiency than those addressed in this study. However, most of these are in the research and development stage, so they are not available on the market.

ConclusionsThe research findings indicate that the utilization of α-alumina synthesized from recycled aluminum is a viable approach for the production of direct reflective (DR) coatings, thereby enhancing the performance of photovoltaic and photothermal systems. A comparative analysis of the characteristics of various powder compounds and coatings generated with them is presented in Table 6. While synthesized alumina exhibits a lower diffuse reflective value both as a precursor and a coating, the disparity is sufficiently small to warrant its consideration as a replacement due to its greater hardness and comparable adhesion properties. This discovery paves the way for future research endeavors that explore the potential of waste as precursors to augment the performance of power generation systems. However, it is crucial to recognize that reflectance, the most pertinent characteristic for their optimal application in the fabrication of these optical devices, is influenced by the crystallite and grain size. Consequently, it is imperative to control both the size of these components during synthesis to establish and standardize the radiation they are capable of reflecting. This approach will prevent the heterogeneity of irradiance captured by the various solar systems.

Comparison of the properties of commercial and synthesized alumina.

| Sample of α-alumina | ρd (%) | Hardness | Adherence | Irradiance increase (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Powdered | Coatings | ||||

| Commercial [15] | 93.16 | 75.88 | 4H | 5B | – |

| Synthesized | 92.84 | 72.30 | 5H | 5B | 11.58–12.04 (mean 11.81) |

Referring to the equations and data derived from the simulations; the utilization of DR enables the augmentation of water temperature within a solar heater or the enhancement of electrical power output from a photovoltaic system to a level comparable to that achieved under ideal operational conditions. Accordingly, its production employing precursors sourced from waste recycling significantly mitigates the environmental footprint associated with this renewable energy source for both heating and electricity generation. Economically speaking, the cost of this coating will be quickly amortized in countries where the cost per kWh is significantly higher than in Mexico and, above all, in those where the annual incident solar radiation is low. Likewise, it is imperative to conduct applied research on the choice of substrate since metals are very expensive unless they are also recycled.

Conflict of interestThe authors hereby declare that they have no known financial interests, affiliations, or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the research and conclusions presented in this manuscript.

We extend our sincere gratitude to the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology and Innovation (SECIHTI) for the scholarship awarded to Demetrio Fuentes Hernández, whose CVU is 789052, to support his doctoral research and studies endeavors.