In June of 1866, the Empress Carlota founded the Maternity House in the Department of Secret Births at the Hospice of the Poor. Upon the reinstatement of a republican government, Dr. Ramon Pacheco was appointed as director of the Maternity House. Shortly after, in February of 1868, Dr. Luis Fernandez Gallardo established a pavilion for sick children in the Hospital of San Andres. After realizing this pavilion did not have the adequate conditions to operate properly, and in the need of a children's hospital in Mexico City, Dr. Pacheco merged both institutions on April 2, 1869—with the help of Ms. Luciana Arrazola—and founded the Maternity and Childhood Hospital, the first institution for the care of ill children in the independent Mexico. Ever since it was founded, Dr. Eduardo Liceaga was in charge of the children's health. Later, with the help of the presidents Juarez, Lerdo de Tejada, and Díaz, he was able to consolidate the hospital in academic and health services aspects. This noble institution closed its doors on February 5, 1905, upon its incorporation to the General Hospital of Mexico, after 36 years of working for the welfare of Mexican children.

En junio de 1866, la emperatriz Carlota fundó la Casa de Maternidad en el Departamento de Partos Ocultos del Hospicio de Pobres. Con el restablecimiento de la república, se nombró al Dr. Ramón Pacheco director de la Casa de Maternidad. Poco después, en febrero de 1868, el Dr. Luis Fernández Gallardo estableció una sala de niños enfermos en el Hospital de San Andrés. Considerando que esta sala no reunía las condiciones necesarias, y ante la necesidad de un hospital infantil en la Ciudad de México, el Dr. Pacheco —con el apoyo de la Sra. Luciana Arrazola—, fusionó ambas instituciones el 2 de abril de 1869, fundando el Hospital de Maternidad e Infancia, la primera institución de México independiente para la atención de los problemas de salud infantiles. Desde su creación, el Dr. Eduardo Liceaga estuvo a cargo de la atención de los niños; con el respaldo de los presidentes Juárez, Lerdo de Tejada y Díaz, logró la consolidación del hospital en los aspectos asistenciales y docentes. Esta noble institución cerró sus puertas el 5 de febrero de 1905, al ser incorporada al Hospital General de México, después de 36 años de trabajo en favor de los de los niños mexicanos.

In Mexico, specialized medical care for children appeared late, almost a century later than in Europe where, at the end of the eighteenth century, there was a room for sick children at Allgemeines Krankenhaus der Stadt Wien (Vienna General Hospital), and in 1802 it was founded the Hôpital des Enfants Malades (Hospital for Sick Children) in Paris. At that time, Mexico dealt with abandoned newborns. Childcare was less than in diapers. Diseases that decimated children were primarily infectious, for example, tetanus and neonatal sepsis, diarrhea, bronchopneumonia, and measles. Malnutrition was rampant, particularly among children in indigenous areas. The need to take better care of sick children prompted Mexican doctors and medical schools to create conditions for their specialized care.1 The following are the efforts of Mexican women and men to create the first institution aimed at taking care of sick children in our country.

2The Children's and Maternity Hospital of President JuarezThe first attempt to promote child health care in the nineteenth century was the initiative of President Juarez, who on March 25, 1861, through Marcelino Castañeda, general of Public Charities, commissioned the enlightened and patriotic teachers of medicine, Gabino F. Bustamante and Juan N. Navarro, to evaluate the establishment of a maternity house and a children's hospital. They should dictate whether they thought possible that these institutions were founded in the House of Expósitos or in other hospitals in the City.2

A week later, Bustamante and Navarro answered the following: “In order to comply with the order of the Hon. Minister of the Interior, in which he warned us to consult him about the establishment of a children's hospital and a maternity house, we visited the House of Expósitos and the Hospital de Terceros. The frist place is small for the number of children that inhabit it (about 300). Thus, it is not only impossible to establish a hospital there, but in our opinion, the Government should expand the land with the purchase of some of the adjacent houses. Even if the locality lends itself to its extension, it would not be advisable to gather sick children with the healthy ones at the same place, since it is well known that in the first years of life all eruptive fevers belong to contagious diseases, such as measles and scarlet fever. These reasons make it necessary, in our opinion, to abandon the idea of establishing a hospital in the House of Expósitos. On the other hand, the Hospital de Terceros is a building that, due to its situation and distribution, seems to us appropriate for the establishment of the Maternity House and Children's Hospital. There are several separate pieces can hold up to 16 to 20 beds for births and some classrooms, which can be exploited perfectly for the placement of sick children”.3

Finally, on November 9th, 1861, President Benito Juárez informed that the Congress had promulgated the following decree: “Article 1: establishes in this capital a hospital for maternity and childhood; Article 2°: the building called Hospital de Terceros de San Francisco is intended for its establishment; Article 3: The government will regulate this establishment”.4

In relation to the above, Dr. Nicolás León commented in his book “Obstetrics in Mexico” that, in compliance with this decree, the Hospital for Maternity and Childhood was established in the Hospital de Terceros, with the reduced number of beds allowed by the anguished circumstances of the treasury at that time of war and foreign invasion. According to Dr. Leon, the first director was Dr. Manuel Alfaro and the midwife in chief Ms. Dolores Román. However, he also said he did not know the details of what had happened at that hospital, and he could not figure out if life was precarious and for how long, or if it perished with the change of government.5

The lack of certainty about the founding of the hospital was reinforced by a new decree issued by President Juarez on January 17th, 1862, only two months after the first. This stated that for better compliance with the third article of the decree of November 9, 1861, the Ministry of Foreign and Interior Affairs would destinate another location for the establishment of the House for Mothers and Children.6 The reason that led President Juarez to pass on what the Congress ordered is unknown, although some reports indicate that the cause was the sale of the magnificent building of the Hospital de Terceros to the French citizen Justo L. Caresse; therefore, the decree of the Congress was not accomplished, and the Maternity Hospital and Children was never founded.6–8

3The Maternity House and the San Carlos Asylum of Empress CarlotaAlthough the Maternity House and the San Carlos Asylum were not dedicated to the care of sick children, it is necessary to point out their existence since they are the continuation of President Juarez's project. This project was completed during the restored republic with the establishment of the Maternity and Childhood Hospital as a result of the fusion of the Maternity House with the Sick Children's room of the Hospital of San Andrés.

With the arrival of Empress Carlota to our country, the creation of a Maternity House took a more lasting form. In July, 1863, the political prefect of Mexico City commissioned Dr. José María Andrade to visit the charitable establishments of the city. Dr. Andrade was accompanied by Mr. Joaquín García Icazbalceta who, at the end of the tour, wrote a report in which he mentions the following: “there exists in the Hospice for the Poor an entirely strange department that produces ills of consideration; I’m talking about the Department of Hidden Births. I will excuse myself from entering into explanations on this point, merely making sure that the decorum, morality, reputation of the people in the hospice, and the good name of the establishment require that, it disappears as soon as possible, as it has been asked the directors many times. Although separated from the hospice, it is communicated through a small door, having another one in the street of Revillagigedo; used by women who need to go and hide the consequences of a fragility. This Department is necessary in a capital, because even if it does not have much use, it is enough that it sometimes serves to make convenient to keep it, even if it helps to avoid only one infanticide at the end of the year. However, it would be more useful if it is given more space and it is divided into two sections, one small for hidden deliveries and a larger one for deliveries that do not require secrecy”.9

On the other hand, Dr. Manuel S. Soriano reported that in 1865 he was called by Minister Manuel Siliceo, Minister of Public Instruction and Culture, on behalf of the Archduchess Carlota, who knowing that during his stay in Paris he had studied maternity regulations, asked to associate with Dr. Lino Ramírez to prepare a draft decree for the creation of a maternity home and two regulations, one general and one particular for the same house.10 Dr. Soriano reported that he told Minister Siliceo that he would not participate in the ideas of the Intervention and the Empire, although he was insisted that it was a humanitarian matter corresponding to his profession, in which he could render a service to his country. Soriano consulted with several people the matter, among them to the honorable patriot Mariano Riva Palacio, and all advised him to accept that honorable and beneficial commission. Finally, after two meetings with his friend Dr. Lino Ramirez, both agreed that Dr. Ramirez would write the internal rules draft and Dr. Soriano would write the general regulations and the creation decree. Each of them worked individually, reviewed their work and presented it to the corresponding Superiority.10

During the meetings with Dr. Ramírez, Soriano stated the delay in Mexico regarding the practical study of obstetrics due to the lack of a clinic, so the Maternity House should become the official obstetrics hospital of The School of Medicine. For the above, he proposed to Archduchess Carlota to buy in Paris several objects indispensable for that study. When the equipment arrived, Dr. Soriano and his teacher, Dr. Ignacio Torres had the satisfaction of going to the Palace to review the material and admired the collection of Auzoux on egg development.10

On June 7, 1865, after hearing the opinion of the General Council of Charity, Maximilian issued the following decree in Puebla: “1°. Under the protection of my beloved wife, and in commemoration of her birthday, a Maternity House is established in this court; 2°. Our government minister is in charge of the execution of the decree, in consultation with us the location of the new establishment, the budgets of its erection, regulations to be followed and anything that would lead to the early realization of this kind thought”.5

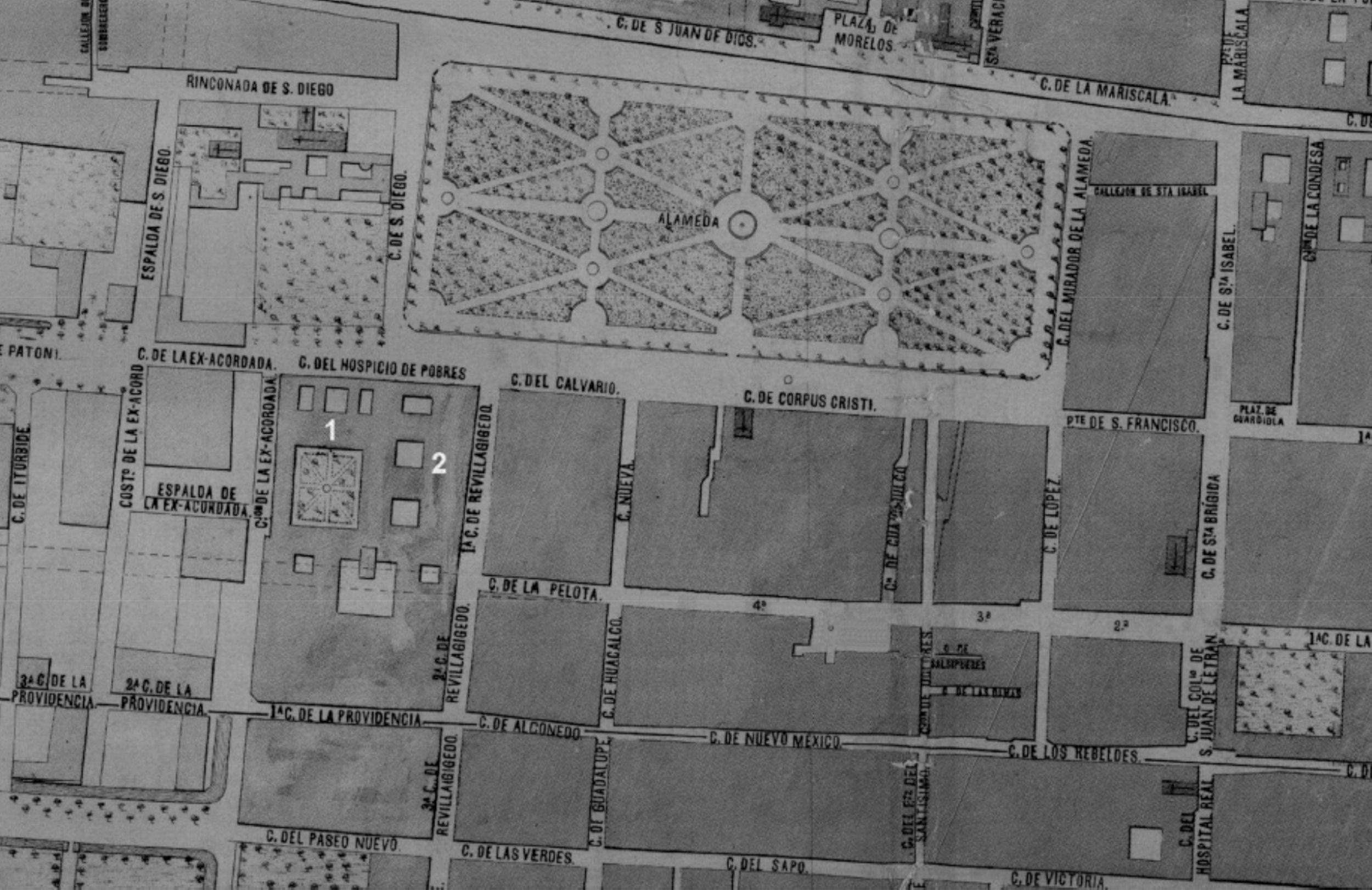

Works on the arrangement of the premises for the Maternity House began, it was chosen the same place that occupied the Department of Hidden Births of the old Hospice for the Poor, being entered by the 1st street of Revillagigedo (Figure 1). The Imperial government allocated funds for the work, but they were insufficient. It was necessary to ask for the philanthropy of Mr. Antonio Escandón, a member of the General Council of Beneficence, who provided the necessary sum to finance the works. One year after the decree was issued, on June 7, 1866, the Minister of Government, Ing. José Salazar Ilarregui, inaugurated the work, which was managed by Architect Juan M. de Bustillo. In addition, the House Asilo de San Carlos (named after its benefactor) was built in the same location in which people in poverty situation could leave their children and go to work since the children would receive food and education. Unfortunately, this useful idea was not realized due to the various political events that followed.5,11,12

In spite of the efforts of the administrators and the right offices of Mr. Francisco Villanueva, councilman of the Charity, the house did not prosper. However, the fundamental things never lacked, since the Empress was always watching over the contribution of resources. In such state was the Maternity Hospital on June 21, 1867, when the Republican army, under General Porfirio Díaz entered Mexico City sealing the triumph of the Republic.5

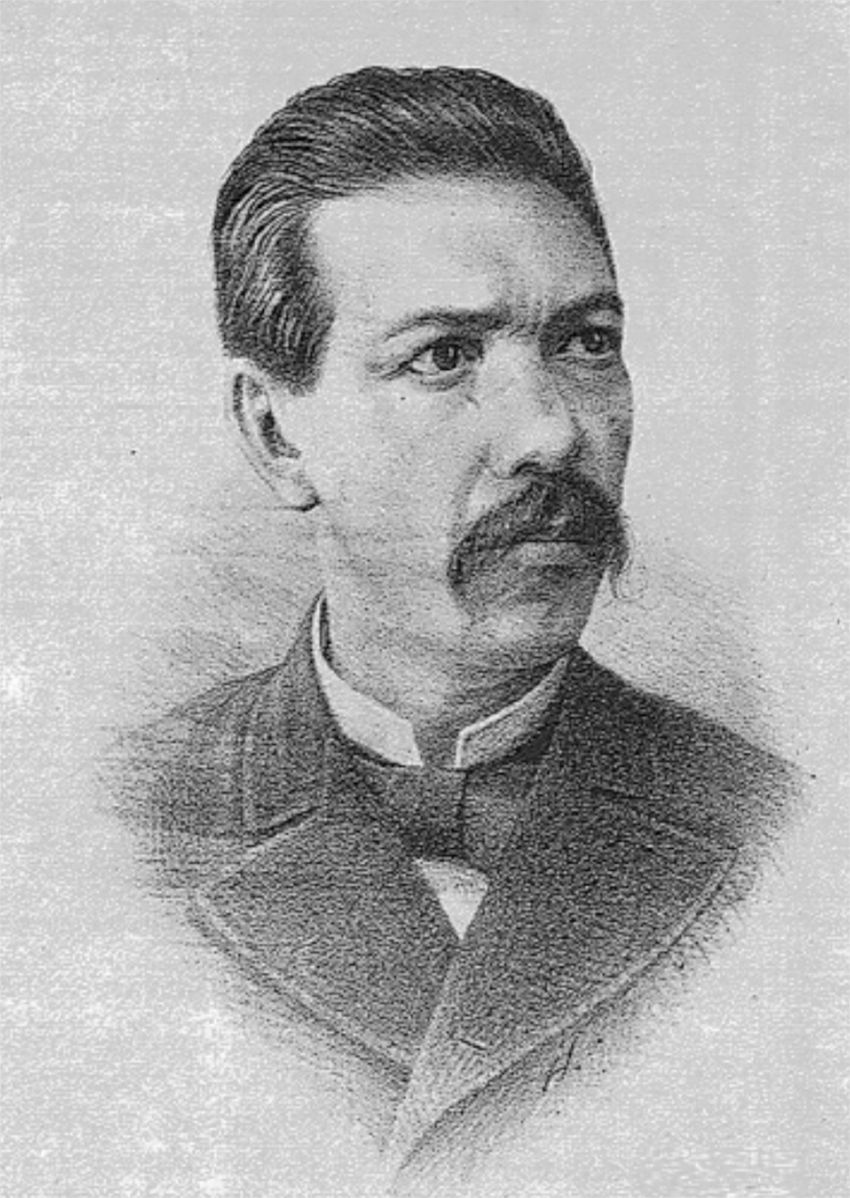

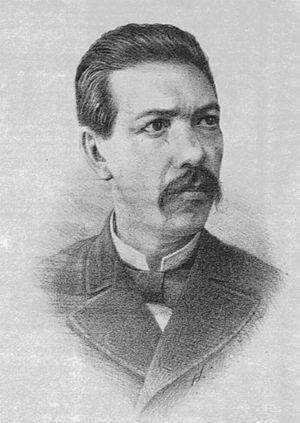

Afterwards, as an ex-councilman, Mr. Villanueva feared that in the new order of things the existence of the Maternity House would be endangered. To avoid this, he placed the institution under the protection of Mrs. Luciana Arrazola de Baz, wife of the celebrated Mr. Juan José Baz, newly appointed governor of the Federal District. Ms. Arrazola managed that General Diaz appointed her as head of the Maternity House, and she designated her nephew, Dr. Ramón F. Pacheco, an eminent and competent physician in the practice of Obstetrics (Figure 2), as director. The new head prepared a report stating the deficiencies of the premises and the modifications that should be made. For this reason, Mr. Baz addressed the Minister of the Interior, Mr. Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, requesting the assignment of the building of the Casa Asilo de San Carlos to carry out the necessary expansion works that the Maternity House required. This allowed the construction of three spacious and airy rooms for sick women at the time of delivery, leaving the old for the other patients.5

Dr. Ramón F. Pacheco Rodríguez. Creator of the Children's and Maternity Hospital.5

Dr. Luis Fernández Gallardo, the counselor of the Charity Commission of the City of the Federal District, promoted the creation of a 16-bed service for the care of sick children in the Hospital de San Andrés, which was founded on February 7th, 1868, by agreement of the town council. The arrangements were supported by city hall and by sister Juana Antía, superior of the sisters who served in the hospital. However, the opening of the room was only possible thanks to the charity of Don Nicolas de Teresa, Mr. Pio Bermejillo and other people who provided the cots, clothes, and tools needed for the new department. The Council also opened a competitive process to select the doctor in charge of the new hall, being appointed by the jury Dr. Eduardo Liceaga, and Dr. Abraham D. Gutiérrez as his attached practitioner.5,11,12

In 1868, Dr. Pacheco was commissioned by the Superior Council of Health to visit the hospitals, in order to know their defects and their needs. In his report, he mentioned that he observed the existence of hundreds of unhappy children who daily went to ask the municipal charity for the relief of their pains and the preservation of their lives. Also, he reported that the sick children's room at the Hospital de San Andrés was insufficient and did not meet all the requirements to provide proper care. Dr. Pacheco added that he felt his heart compressed in pain when he found patients suffering from the worst hygienic conditions since, in his visit, he found that in a room of nine columns there were 16 patients in beds and three in beds on the floor. Only two not very large windows gave light and air to this room, the rest of the ventilation was received from previous infirmaries that were crowded with patients who passed them an unbreathable air. In addition, the children were together, with the danger that if someone came in with an infectious condition, it would infect his or her neighbors, since the narrowness of the place would not allow their isolation, it was potentially leading to a severe childhood epidemic. It was so painful the impression that this picture produced in Dr. Pacheco that he promised to find a place to improve this situation. In order to benefit a greater number of children, preserve them in their families, and providing older citizens for the country without harming the municipal funds or increasing the expenses they demanded from charities.5

5The foundation of the Maternity and Childhood HospitalAfter part of the San Carlos Asylum building was used for the expansion of the Maternity House and seeing that there was still enough ground for another building, Dr. Pacheco had the idea of founding a children's hospital, complying in this way with the decree of President Juárez. He communicated his idea to Mrs. Arrazola, who enthusiastically welcomed it and offered her personal support and valuable influence.5

Due to the above, and based on his observations, Dr. Pacheco requested the City Hall to move the nursery that was at the Hospital de San Andrés to the annexed part of the Maternity House, hoping that the change of place would give the children an improvement in the hygienic conditions in which they found themselves, a remarkable economy in the expenses of the municipality, and little by little shaping the hospital for children urgently required by the city. This was crucial to Dr. Pacheco, because as he said, “these unfortunate beings have been deprived of the benefits of medicine and the care and attention that public charity owes them”.5

In response to this request, the Hospital Commission in charge of deciding on the reforms proposed by Dr. Pacheco, approved on February 2nd, 1869, the following: “The section for sick children that is at the Hospital of San Andrés will be relocated at The House of San Carlos attached to the Maternity, as a Department of the latter. The older and younger practitioners of this section will continue to perform the same assignment in the new premises, and the current director of the Maternity House will be in charge of the management of both establishments, which will henceforth be known as the Maternity and Childhood Hospital. Also, the budget that previously passed to the Hospital de San Andrés by the children's section would be appointed, since its moving, to the administration of the Maternity Hospital”.5

On March 31st, 1869, the children who were then in the Hospital of San Andrés were moved, and on April 2nd at 10 o’clock in the morning, the inauguration took place. The opening act was led by the governor of the Federal District and the municipal administrator José Ma. Del Castillo Velasco, who took the floor on the part of the City to express the satisfaction of which he saw the establishment of the Children's Hospital, unique in its kind in the country, and the success of the efforts made by Ms. Arrazola to put him in the conditions in which it was. He also appointed Dr. Ramón F. Pacheco as chief director of the Maternity and Childhood Hospital.5,11,12

6The work of Dr. Eduardo Liceaga at the Maternity and Childhood HospitalOne week later, in compliance with the decree, Dr. Eduardo Liceaga was appointed doctor of the children's section (Figure 3). The service for sick children was established in three rooms, one for the boys, another one for the girls and another long and narrow room where children with contagious diseases were treated. The floors of the rooms were paved with brick and lime painted walls.5,11

Dr. Liceaga tells in his memoirs that the director of the hospital had a particular commitment, and on one occasion he said to him: “since you are my subordinate, I impose upon you the obligation to sleep in the establishment to attend anything needed during the night”. Dr. Liceaga replied that his appointment required him to visit the sick every morning and return in the afternoon if there were any serious children or an accident. He also stated that the director of the establishment had an obligation to attend to all deliveries that were verified in the hospital, regardless of the hour, and that he only had the appointment of doctor for the children and not the for Maternity, for which he received only the modest remuneration of $ 15.00 per month, while the director received $ 100.00. Dr. Liceaga proposed to use his small salary to pay a young doctor who performed the work at night since he was not in the pediatric service because of the little remuneration he received but to study childhood diseases.13

In his report of 1869, Dr. Manuel Alfaro, councilman of the City Council, stated that the Children's Hospital with its various Departments, bedrooms, refectories, wardrobe, assortment of instruments, bathrooms, garden, pantry, etcetera, was a model of Charity establishment. In addition, the sick children were tenderly cared for by the workers of the house, in particular by the clever Dr. Liceaga. In early 1870, the Interior Ministry removed Dr. Ramón Pacheco from the direction and appointed Dr. Eduardo Liceaga as the new director of the establishment and Dr. Aniceto Ortega as director of Maternity.5

As soon as the new service of the Children's Hospital was organized, Dr. Liceaga realized that it was insufficient for a population as large as that of Mexico, so he expanded it, creating a free consultation service for poor children, whatever their illness was. The consultation was established on the lower floors of the building, in a large room and with an attached waiting room. Soon it became pretty demanded, and Dr. Liceaga had to request the free assistance of his companions and friends, and that of his practitioner, Mr. Jesús E. Monjarás. Thus, physicians such as Dr. Francisco Chacon, Nicolás San Juan, Ramón Icaza, Manuel Barreiro, head of the Maternity Clinic, as well as the practitioners who had previously served: Pedro Noriega, Francisco Hurtado, José Buiza, Lamberto Anaya, Miguel Márquez and Rafael Souza began to see patients. Due to its success, it was necessary to extend the consultation to patients suffering from surgical ailments of any age and sex, and doctors José and Román Ramírez, Vicente Morales, Nicolás Ramírez de Arellano, Agustín Reza, Manuel Garmendia from Veracruz, González Amezcua from San Luis Potosí, Agustín Villalobos from Guanajuato, Francisco Bernáldez, Alfonso Ruiz Erdozáin, Francisco Hurtado and Florencio Medina concurred as well.5,13

As the clientele increased steadily, it was necessary to perform numerous surgical operations. The room was insufficient for two or three simultaneous surgeries, and the room did not have a zenith light, so it was necessary to build an amphitheater for surgeries, to improve the Department for Children and to establish isolated rooms for those affected by infectious diseases. All this required money and an opportunity to acquire it became available. General Diaz, who was already known throughout the country for his victories against the French army and his allies, for his managerial skills and because his unflinching honesty, had expressed his desire to visit the Maternity and Childhood Hospital. Dr. Manuel Fernández, a friend and fellow student of Dr. Liceaga, welcomed him.13

After showing him the Maternity Department, the sick children and the narrowness of the operating room, General Diaz was told that there was a need to improve these three departments, and he was asked to support this with his influence and that of his politician friends a petition to the Congress for $ 10,000.00, assuming that it would be enough to carry out the mentioned improvements. General Diaz kindly accepted the claim and offered his help. The request was submitted to Congress and was supported by the deputation of Oaxaca and 35 other deputies. This allowed it to proceed immediately to its study by a commission, which did not delay in ruling favorably. Dr. Liceaga said that it was the first service of public interest owed to Gral. Diaz, and that at that time, 1874, began a friendship that linked both until his death.13

Even when the account was approved, the money did not reach the hospital, probably because of the shortage in the national treasury; while it arrived, Dr. Liceaga began to talk to his friends. Mr. Emilio Pardo offered to bring from England mosaic floors to pave the halls and corridors of the Children's Hospital, covering their price with the legacy of Mr. Clemente Sanz, intended for charitable works. When the bricks arrived in Veracruz, Mr. Pardo handed the bill to Dr. Liceaga for more than $ 700.00, forgetting that he had offered them. It was necessary to inform Mr. Lerdo, who was then President and responded that Mr. Pardo used to have such distractions, and ordered that the debt was paid from the $ 10,000.00 that the House had voted.13

When General Diaz came to power in 1876, he remembered the hospital's bill from the budget and authorized it to be spent. Work began slowly, according to the sums provided by the Treasury. It was necessary to appeal again to the friends of Dr. Liceaga: the bathroom was built at the expense of Lic. Joaquín Obregón González; the small room, at the expense of Don Gregorio Jiménez from Guanajuato; the room in which the medical service was given was paid by Mrs. Antonia del Moral de Jiménez; the cost of the girls’ room was covered with the donation of the young ladies Sevilla, from Veracruz. The oil painting in the nursery was financed by Mr. Juan Abadiano, the hospital administrator, and by Dr. Liceaga himself. The remodeling included replacing old beds with iron beds with white oil painted grilles, soft mattresses, new bedding, and white muslin pavilions. Other benefactors were Ms. Mier de Castillo, Müller and Pedraza, Messrs. Joaquín Othón Pérez, Rafael Lamadrid, and Tiburcio Montiel; the latter favored as in many ways as he could when he was governor of the Federal District.13

Instead of the room for surgeries, Dr. Liceaga designed a monumental amphitheater (at that time, before Lister, the rules that now rule the construction of the operating rooms were not known), for which General Vicente Riva Palacio provided the work materials he had intended to use in Chapultepec Castle, but that were never placed (quarry carved stones, large windows of iron frames with crystals and columns of one piece to support ceiling). With these elements, an amphitheater with a semi-circular form adorned with the columns was constructed. The roof was made of steel rails, and a skylight was installed to provide overhead light, given by Ms. Catalina Barrón de Escandón. Thus the amphitheater, an annexed room for the explorations of the eyes and the sick that could not be explored in the common room, was completed, and the operating beds were bought. When the work was finished, it was inaugurated by Mr. Carlos Diez Gutierrez, minister of government, who was kind enough to give the name “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga” to the consulting office, setting a commemorative plaque at the amphitheater.13

Children who arrived with measles and smallpox were isolated in a four-bed room, resulting in three beds being put out of service for each sick child; thus, it was necessary to build four small isolated wooden rooms, with the necessary furniture and tools for children with contagious diseases. This allowed their isolation, preventing the spread of illness. In addition, unvaccinated children received their vaccinations on their arrival at the hospital.13

The doctors who were associated with Dr. Liceaga to give the consultation and to perform surgeries, formed a society that never had nor regulation nor name, but did had a tacit rule: to assist the patients with charity and sweetness, to solve the necessity of procedures and proceed in accordance with the opinion of the majority. It should be noted that Dr. Liceaga allocated his fees—which had been raised to $ 40.00 per month—for the purchase of surgical instruments, which formed an arsenal that sufficed for all the needs of the service. In addition, Dr. Manuel Izaguirre, commissioned by the Public Beneficence, managed the statistics of the patients being attended, the diseases that took them to the surgery and the surgical operations that demanded their treatment. The statistics were published monthly and records which stated that between 10,000-11,000 patients per year were attended there.13 Also, Rivera Cambas pointed that the mortality in the Children's Hospital was between 20 to 25%, certainly significant, but much lower than that of some European nations at that the time.14

The education of children was one of the concerns of administrators. Since then, the possibility of having a school attached to the hospital had been considered, but key elements were lacking. Fortunately for the children, the establishment was administered by Mr. Juan Abadiano, distinguished man for his good education, his intellectual culture, his noble heart and his love for childhood. He made them eat at the table with tablecloths, taught them the use of cutlery, cleaning habits, frequent bathing and changing of clothes when necessary. The discipline to which he accustomed them was so great that it admired the visitors who came to the hospital at the time of the medicines, as they watched the children line up and receive spoons, powders or cures without resistance on their part or violence from the nurse that administered the medication. Some ladies of the society went spontaneously and assiduously to give them religious education, while Mr. Abadiano taught them geometry with solid wood bodies and physical geography, drawing in a sandblasted courtyard and with a wand the continents and the islands, the course of rivers and mountainous places. On the maps, he taught them the limits and names of different countries, capital cities, etcetera. That admirable man was a true intellectual father for the children.5,13

In his book “La beneficencia en México”, Juan de Dios Peza comments that in one occasion Minister Lerdo de Tejada arrived at the hospital and, at the suggestion of the director, asked the children several questions to ascertain their progress, being deeply moved when he heard one of the littlest ones relate the geographical division of the Mexican republic, pointing out the extent, products, and importance of each state. The Minister ordered to give $ 1000 pesos for the establishment, which were used to raise the upper part of the building.12

On February 14th, 1877, Dr. Miguel Alvarado, director of Public Charities, approved that a second Department of Childhood should be available for the sick children of the Poor Hospice. Thus, the hospital was divided into two sections, in which children between two and ten years of age of both sexes were treated. Patients were received along with their mothers, who remained in the establishment during the whole illness and performed the domestic service of the room. The first section had three infirmaries: one for girls, one for boys and one isolated for those with contagious diseases. The second only had two, one for girls and one for boys. Each room had an adequate number of patients; food was administered according to the physician's prescription and medicines were prepared in the pharmacy of the accredited professor Victoriano Montes de Oca and by the pharmacy of the Hospital Morelos.3,13

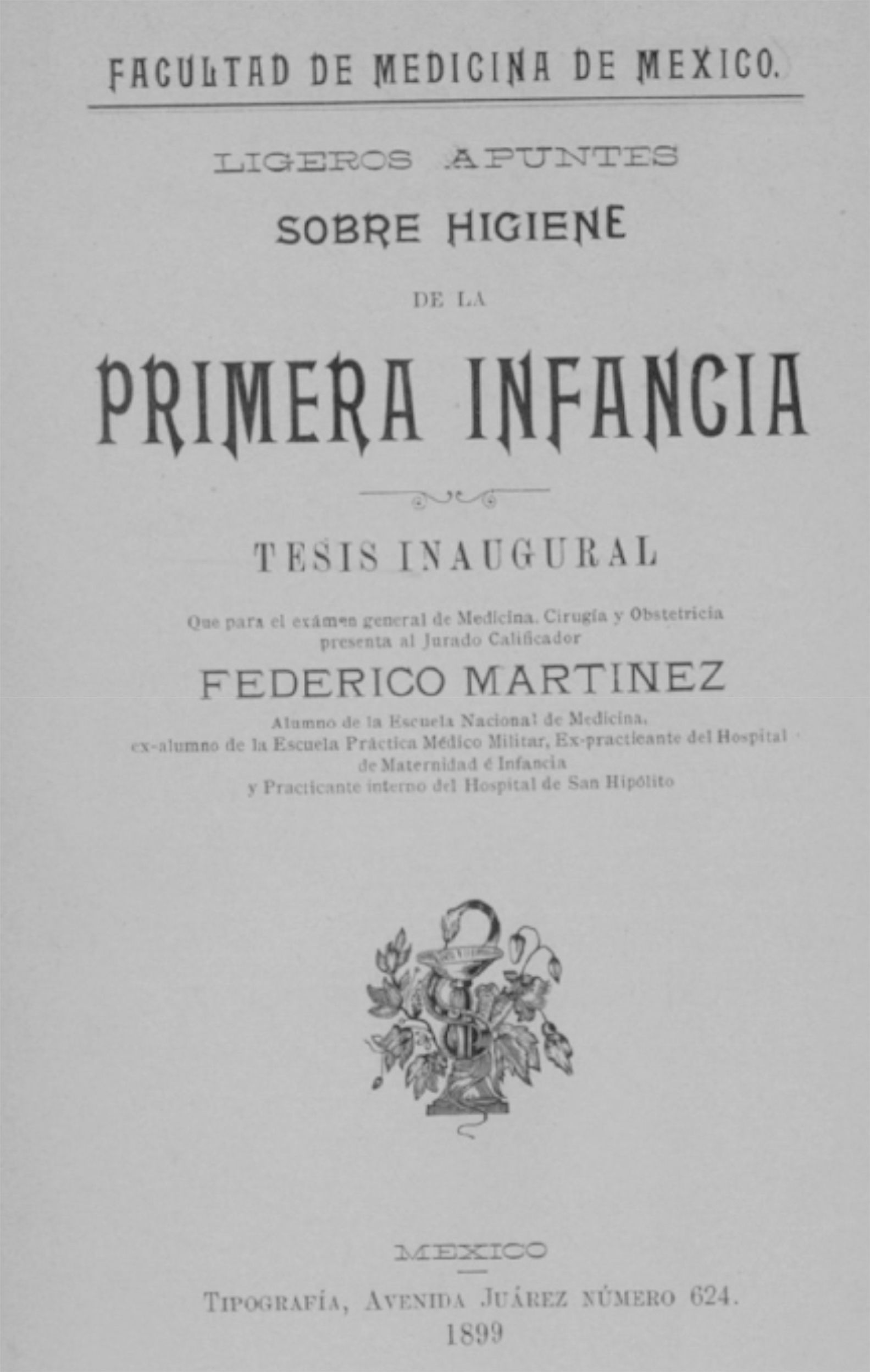

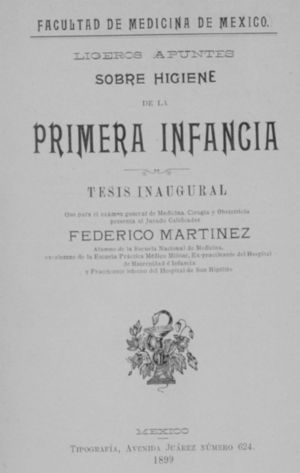

In the Maternity and Childhood Hospital, not only the attention of the sick children flourished but also the attention for newborns in their various modalities. This encouraged the students of the School of Medicine, particularly those who had been practitioners of this hospital (Figure 4), to do their inaugural theses with pediatric and neonatal subjects, which they dedicated to their teachers. Of them stands out, the one of Mariano Herrera titled “Some considerations on Pediatrics”. The one of Francisco García Luna: “Utility of the incubators and their complement, the gavage”. The one of Federico Martínez: “Light notes on hygiene in early childhood”; and that of Alberto Limón: “Advantages of late ligation of the umbilical cord”, among others.

The thesis of Mariano Herrera, presented in 1881, deserves a special mention, since it actually constitutes a textbook, because in its 200 pages—unusual extension at that time—addresses the core aspects of pediatrics: 1.- Anatomo–physiological considerations, 2.- Pathological considerations, 3.- Clinical examination of the child, 4.- Therapeutic considerations, both medical and surgical and 5.- Hygienic considerations. In the introduction, Mariano Herrera points out that the reasons that led him to take up this issue for inaugural work were its importance and the almost complete lack of knowledge that students had about the subject when leaving the vocational school. Regarding this work, Dr. Francisco Flores pointed out that, at the end of the 19th century in Mexico, there were almost no works on pediatrics, except for “a small manual of pediatrics and studies on child pathology” written by Mariano Herrera and dedicated to “the eminent specialist in children's diseases, Dr. Eduardo Liceaga” (Figure 5).5,15 In 1885, due to the death of Dr. Ildefonso Velasco, a very distinguished physician and president of the Superior Health Council, the members of the Council proposed Dr. Liceaga as his substitute, so he no longer could direct the Hospital for Maternity and Childhood, and Dr. Agustín Villalobos was appointed head of the office; after his death, that office was entrusted to Dr. Francisco P. Bernáldez, who continued to work with Drs. Hurtado, Ruiz Erdozáin, Chacon, Barreiro, Morales, Souza and Medina.13

Dedication of the inaugural thesis of Mariano Herrera and Jayme to Dr. Eduardo Liceaga, a distinguished specialist in childhood diseases, 1881.15

Another important aspect was the creation of the tenure of Clinical Management of Childhood Illness (1892), which was entrusted to Dr. Carlos Tejeda Guzman, who in 1890 was granted a scholarship by the government to study childhood diseases and start that a new clinic in Mexico. Dr. Tejeda spent 18 months in Paris attending the clinics Lancereau, Hutinel, Saint Germain, and Granchet and spent six months visiting children's hospitals in London, Berlin, and Italy. He returned to the country and received his appointment as Professor of Clinical Management of Childhood Illness on May 12th, 1892. Classes were held at the Hospital for Children three times a week: Tuesdays and Thursdays, the lessons were carried out at the bedside, for which students have to take a medical history under the supervision of the teacher, in order to establish the diagnosis and institute treatment; Saturday mornings, the teacher offered a conference on the most important clinical case of the week, since they did not have a textbook and only oral lessons were offered.16–18

7The closing of the Children's and Maternity HospitalOn February 5th, 1905, the President Porfirio Díaz, inaugurated the new General Hospital, a monumental work planned since its inception by Dr. Eduardo Liceaga. The new hospital had 55 beds for hospitalized pediatric patients, 31 in the “Hall 23” where children with non - infectious diseases, predominantly surgical, were attended by Dr. Eduardo Vargas; 24 children in the “Hall 29”, where care was offered to patients with infectious diseases by Dr. Manuel G. Izaguirre. Healthcare for newborns was provided by Dr. Manuel Perea in the “Hall 24”, the first maternity in the hospital. Its creation led to the closure of the hospitals “San Andrés,” “González Echeverría” and for Maternity and Childhood, which became the main consulting room.19

Thus, after 36 years of providing benefits to Mexican children, the Children's Hospital disappeared, having been the first children's hospital in Mexico, an institution that, on behalf the initiative of its director (Dr. Eduardo Liceaga), and the help of presidents Benito Juárez, Sebastian Lerdo de Tejada and Porfirio Díaz, was enlarged and embellished, becoming the center for the first Mexican pediatricians.20

Conflict of interestThe author declares he does not have conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Baeza BMA. Orígenes de la pediatría institucional: el Hospital de Maternidad e Infancia de la Ciudad de México en el siglo XIX. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2017;74:70–78.