Introducción: La prueba Evaluación del Desarrollo Infantil (EDI) es una herramienta de tamiz para la detección oportuna de problemas del desarrollo, diseñada y validada en México. Para que sus resultados sean confiables, se requiere que el personal que la aplique haya adquirido los conocimientos necesarios previamente, a través de un curso de capacitación en la unidad de salud que labore. El objetivo de este trabajo fue evaluar el impacto de un modelo de capacitación impartido al personal que trabaja en atención primaria en seis entidades federativas en México. Lo anterior mediante la comparación de los conocimientos adquiridos en la capacitación.

Método: Se realizó un estudio de evaluación de antes y después, considerando como intervención el haber acudido a un curso de capacitación sobre la prueba EDI de octubre a diciembre de 2013.

Resultados: Se incluyeron 394 participantes. Las profesiones fueron las siguientes: medicina general (73.4%), enfermería (7.7%), psicología (7.1%), nutrición (6.1%), otras profesiones (5.6%). En la evaluación inicial, el 64.9% obtuvo una calificación menor a 20. En la evaluación final, disminuyó al 1.8%. En la evaluación inicial aprobó el 1.8% comparado con el 75.1% en la evaluación final. Las preguntas con menor porcentaje de respuestas correctas fueron las relacionadas con la calificación de la prueba.

Conclusiones: El modelo de capacitación resultó adecuado para adquisición de conocimientos generales sobre la prueba. Para mejorar el resultado global se requiere reforzar los temas de calificación e interpretación de los resultados en futuras capacitaciones, y que los participantes realicen una lectura previa del material de apoyo.

Background: The Child Development Evaluation (CDE) test is a screening tool designed and validated in Mexico for the early detection of child developmental problems. For professionals who will be administering the test in primary care facilities, previous acquisition of knowledge about the test is required in order to generate reliable results. The aim of this work was to evaluate the impact of a training model for primary care workers from different professions through the comparison of knowledge acquired during the training course.

Methods: The study design was a before/after type considering the participation in a training course for the CDE test as the intervention. The course took place in six different Mexican states from October to December 2013. The same questions were used before and after.

Results: There were 394 participants included. Distribution according to professional profile was as follows: general medicine physicians 73.4%, nursing 7.7%, psychology 7.1%, nutrition 6.1% and other professions 5.6%. The questions with the lowest correct answer rates were associated with the scoring of the CDE test. In the initial evaluation, 64.9% obtained a grade lower than 20 compared with 1.8% in the final evaluation. In the initial evaluation only 1.8% passed compared with 75.15% in the final evaluation.

Conclusions: The proposed model allows the participants to acquire general knowledge about the CDE test. To improve the general results in future training courses, it is required to reinforce during training the scoring and interpretation of the test together with the previous reading of the material by the participants.

1. Introduction

Early child development (ECD) is a process of change in which the child learns to dominate always more complex levels of movements, thoughts, feelings and relationships with others1. It is during this period, which ranges from pregnancy up to 6 years of age, that most brain connections are established and the circuits that will be used during the lifetime are consolidated2.

Early detection of developmental problems are of great importance as it results in arriving at an early diagnosis and timely treatment3. This will favor that the children acquire increasingly complex skills and thus are able to perform age-appropriate activities, consolidating the relevant circuits during critical periods. It has been demonstrated that the judgment of clinical personnel is not sufficient for identifying problems in child development. From this comes the importance of using standardized tools to detect these patients4,5.

A screening test seeks to identify the individual presumed to present some type of disease within an apparently healthy population, establishing their risk of delay. To be useful in ECD, a test must meet the following characteristics5: easy and quick application, economically viable, reliable and previously validated with a suitable gold standard for sensitivity and specificity, which should be >70%.

Different screening tests have been validated and used in different countries in the Americas6. The following are available in Mexico: a) Valoración Neuroconductual del Desarrollo del Lactante (VANEDELA) (Neurobehavioral Assessment of Infant Development) with appropriate properties but that only covers the period from 1—24 months of age7; b) surveillance charts for identifying changes in child development, which cover a period from 1—24 months of age8; c) and the Denver-II test, which has a documented sensitivity (56%)9; d) Prueba de Tamiz para Evaluar el Neurodesarrollo Infantil (PTNI) (Screening Test for Evaluating Infant Neurodevelopment, given at specific ages (12, 18, 24, 36 and 48 months) and whose properties (sensitivity and specificity) were calculated taking as the gold standard weight/age, height/age and anemia10; and e) Evaluación del Desarrollo Infantil (Child Development Evaluation [CDE] for its English translation), which covers from 1–59 months of age, with a sensitivity of 81% and an overall specificity of 61%11 and could reach >80% when each developmental domain is analyzed separately12. The yellow/red results of the semaphore system allow appropriate identification of the differences in the magnitude of development and support differentiated interventions13. When analyzing the available evidence and information, a panel of experts concluded that the CDE test is the most appropriate screening instrument in the context of the Mexican population <5 years of age14. Different studies have been carried out to evaluate the results of the field test15, and this tool is currently recommended for the evaluation of infant development in the primary care setting in Mexico16.

In order for the results of the test to be reliable, it is essential that its administration, scoring and interpretation be standardized. To this end, an application manual was developed17 that contains the format of the test as well as a brief description of the methodology of evaluation for each item as they were evaluated during the validation process of the test along with a complementary manual18, with the goal of serving as consultation material and planned to be read prior to the course. During 2012, a training methodology was designed for application of the CDE test, which replicates the standardization process of the personnel who applied the test during the validation process. From it, a manual was developed for the training of facilitators19 where the course characteristics are described in addition to including initial and final evaluation forms.

With the goal of including the implementation of the CDE test as part of the surveillance and control of the healthy child population <5 years of age who present to the primary care units of the state health services and with emphasis on the population covered by PROSPERA due to being the most vulnerable population, reproduction of 25,000 copies of the application manual was done so that there would be at least one copy available in each health department in the country15. In order for the results of the CDE test to be reliable, personnel who administer the test should have acquired prior knowledge in the health departments with a training course19.

The goal of this study was to evaluate the impact of training for the CDE test on healthcare personnel representing various disciplines, naïve to child development evaluations, who work at primary care facilities. Knowledge of the personnel was compared before and after training.

2. Methods

A before and after evaluation study was done, considering as intervention having attended a training course related to the CDE test.

2.1. Selection of the venues and study population

Training courses were carried out between October and December 2013. For selection of the states, those which at the time of study initiation met the following requirements were considered: 1) population who were beneficiaries of PROSPERA program; 2) no prior training courses on the CDE test; 3) the state coordination of the PROSPERA program had the necessary psychologists for monitoring and supervision of the strategy (at least one per health jurisdiction); and 4) the health services of the entity had planned to begin the application of the CDE test as part of the first level of care after the training course. Six states were selected, in each of them the same training course. The eligible population was considered to be the total participants of the training courses of the CDE test and, as exclusion criteria, not having submitted two evaluations of the course (initial and final).

2.2. Training course

Training courses were done according to the specifications in the Manual for the Training of Facilitators in the Child Development Evaluation (CDE) test19. The objective was to educate participants on the importance of timely detection of child developmental problems and that participants acquire the knowledge necessary for implementation of the CDE test (administration and scoring). Each course was conducted during two consecutive days through sessions with durations of 9 and 6 h, respectively, with a facilitator for 20-25 participants per course.

Each participant had the required reading material for the course (application and supplementary materials) in electronic format, which was provided a week in advance. The courses were taught by trained personnel and with the established standards. In addition, for each course there was a person present who was directly involved in the training of the validation and development of the contents of the facilitator’s manual. The solicitation and the profession of the personnel who attended the training as well as the number of participants were the decision of each of the states based on the manner in which the implementation of the strategy would be carried out. All training sessions met with 100% of the planning, development of the topics and course conduction activities, specified in the evaluation format of the facilitators19.

2.3. Topic content and evaluation of the knowledge acquired in the course

During the course, issues were covered such as an overview of development, structure and organization of the test; an overview of the application; calculation of corrected age; description of the axis evaluation and rating of the test, and how to interpret results.

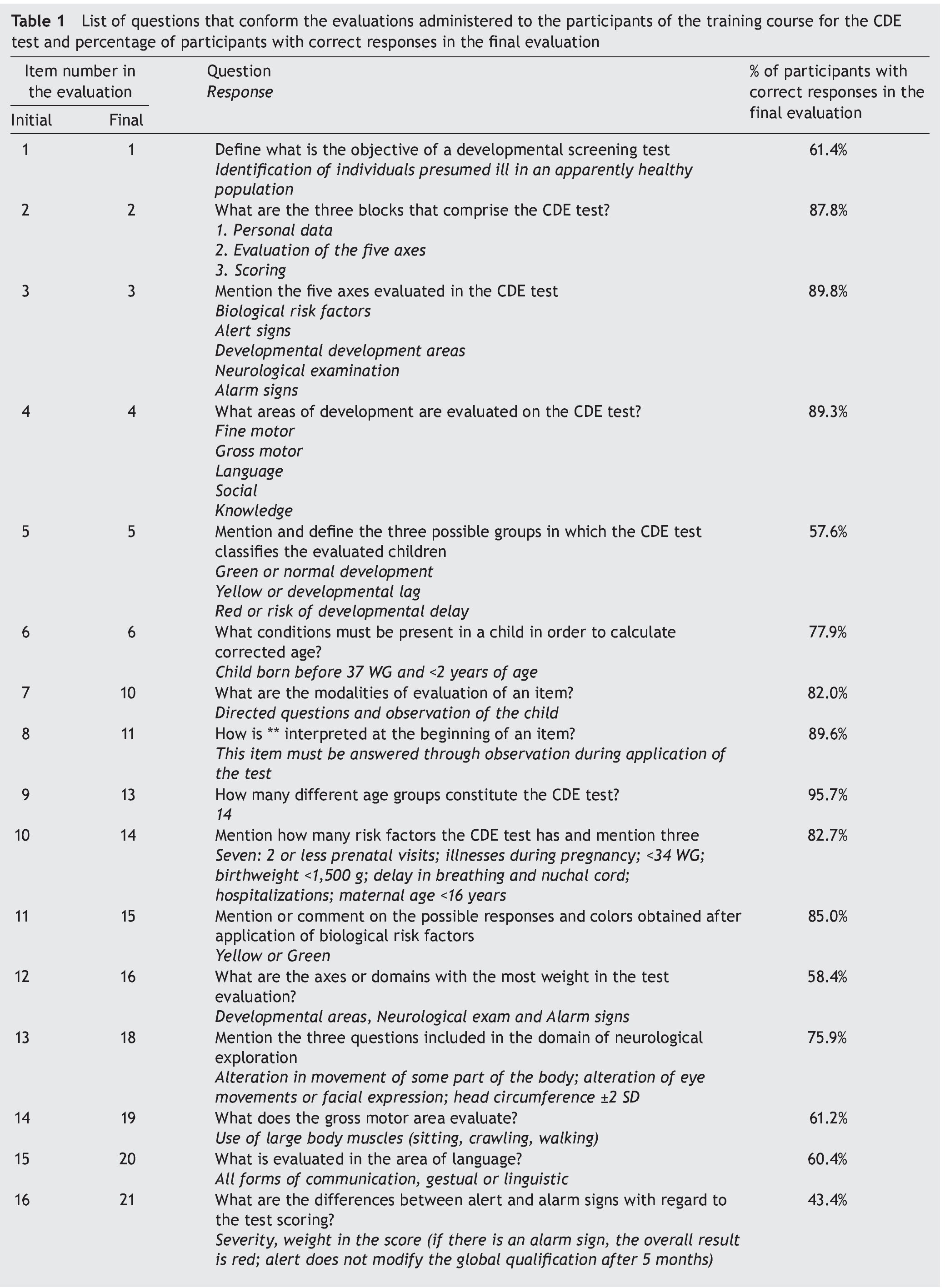

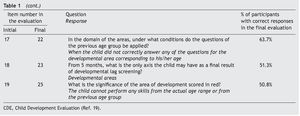

Content evaluation was conducted using the initial and final theoretical evaluation for the course of the CDE test included in addendum 2 of the facilitator manual19. Only 19 of the questions present in both evaluations were scored for this study. Table 1 shows the questions of the evaluation, the number assigned in the initial evaluation and its correspondence in the final evaluation. Because all questions were open response, the points that it should meet were standardized. To be considered as correct, it should cover the totality of the points specified. The score of all the questions was corroborated and captured in a database by three persons who knew and met with the standard of the scoring criteria.

2.4. Study variables

The following data were recorded for each participant: state where training was attended, sex, and profession (general medicine, nursing, psychology, nutrition or other professions classified as administrative activities or social sciences). All categorical variables were mutually exclusive and exhaustive.

Each of the 19 questions had only two possible responses: correct or incorrect. The main study variable was the result obtained in the assessments, both initial and final, defined as the percentage of correct answers obtained by each participant of the total reactions. A participant passed when >60% of answers were correct.

2.5. Ethical considerations

The test was approved by the Ethics, Biosafety and Research Committees of the hospital as part of the HIM/2013/063 project. As part of the course, each participant was notified that an initial and final evaluation would be done and they were informed that the results obtained would have no effect on the work environment. The information was coded with a unique number for each participant by department so as to not deal with personal information.

2.6. Statistical analysis

For description of dichotomous or categorical variables, absolute (n) and relative (%) frequency were used. Description of the study variables (initial and final evaluation) was done using median and interquartile range (IQR) given that a normal distribution was not obtained (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test p <0.05). To evaluate the median of the differences between the initial/final evaluations for dependent samples, Wilcox-on signed rank test for paired samples was used. To evaluate the differences in the distribution between dichotomous or categorical values, χ2 test was used; two-tailed p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical program SPSS v. 20.0 was used.

3. Results

One hundred forty eight persons participated in the six training courses for application of the CDE test (100%). Distribution of the total number of participants by state was as follows: Baja California South (BCS) 11.7% (n=49); Sinaloa 15.8% (n=66); Jalisco 12.9% (n=54); Queretaro 45.7% (n=191); Tlaxcala 7.9% (n=33); Chiapas 6.0% (n=25); 5.7% of the personnel were excluded (n=24) given that in three states some participants were not present in one of the two evaluations: the initial in 66.7% (n=16) and the final in 33.3% (n=8). Of the total participants in these three states, in BCS 14.3% (n=7) missed the initial evaluation and 8.2% missed the final (n=4) and 77.6% (n=38) were included in the study; in Jalisco 16.7% (n=9) missed the initial evaluation and 83.3% (n=45) were included; and in Queretaro 2.1% (n=4) missed the final evaluation and 97.9% (n=187) were included.

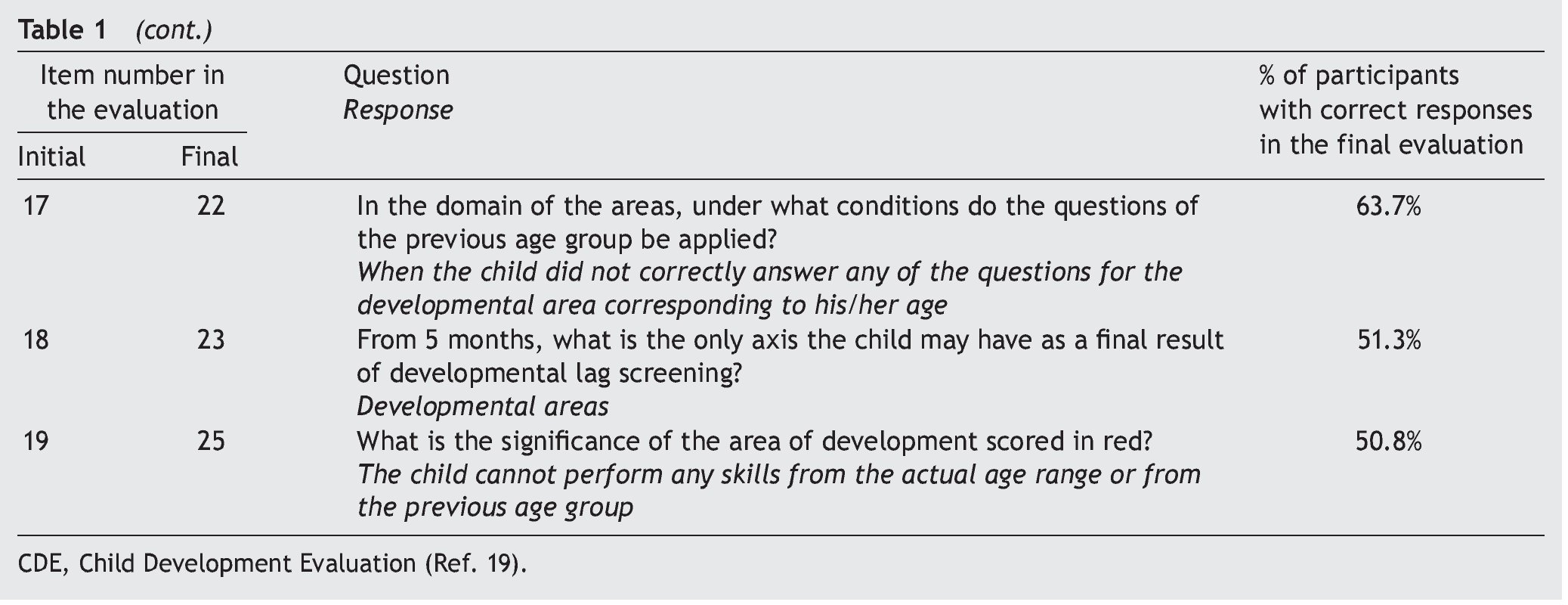

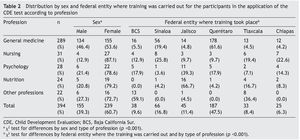

From the total participants included in the study (n=394), 39.3% (n=155) were males and 60.7% (n=239) females. Distribution according to type of profession was as follows: general medicine 73.4% (n=289); nursing 7.7% (n=31); psychology 7.1% (n=28); nutrition 6.1% (n=24) and other professions (social work, administrative) 5.6% (n=22). Significant differences were found in the distribution by gender and type of profession (p <0.001), demonstrated by a higher percentage of women in all professions (>70%) except general medicine where the percentage of women was 53.6%. Significant differences were also found (p <0.001) in the profession of the participants by state: in Sinaloa and Queretaro the majority of participants represented general medicine (84.8 and 95.2%, respectively); in Chiapas, the majority was general medicine (48%) or nursing (28%); and in Jalisco there was a higher proportion of nutritionists (35.6%) or psychologists (24.4%). Of all the states, BCS and Tlaxcala had a higher percentage of participants with other professions (34.2 and 24.2%, respectively). These differences are due to the different opinions of the entities which, according to the established planning, considered that the test should be given by personnel representing a specific profession. Table 2 describes the distribution of the participants by profession, according to sex and state. The profession was taken as baseline for the analysis and interpretation of the results of the evaluations.

3.1. Results of the initial and final evaluation

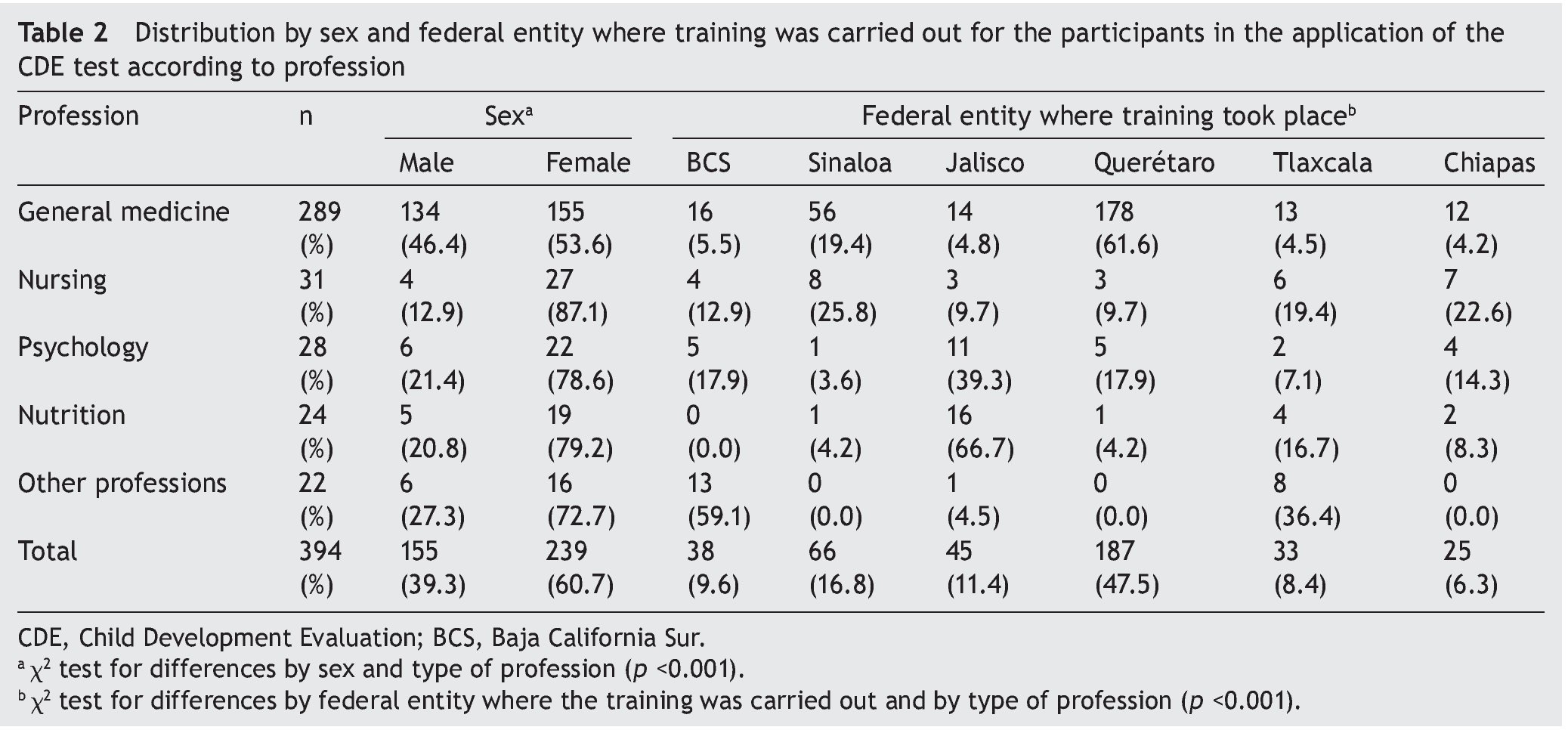

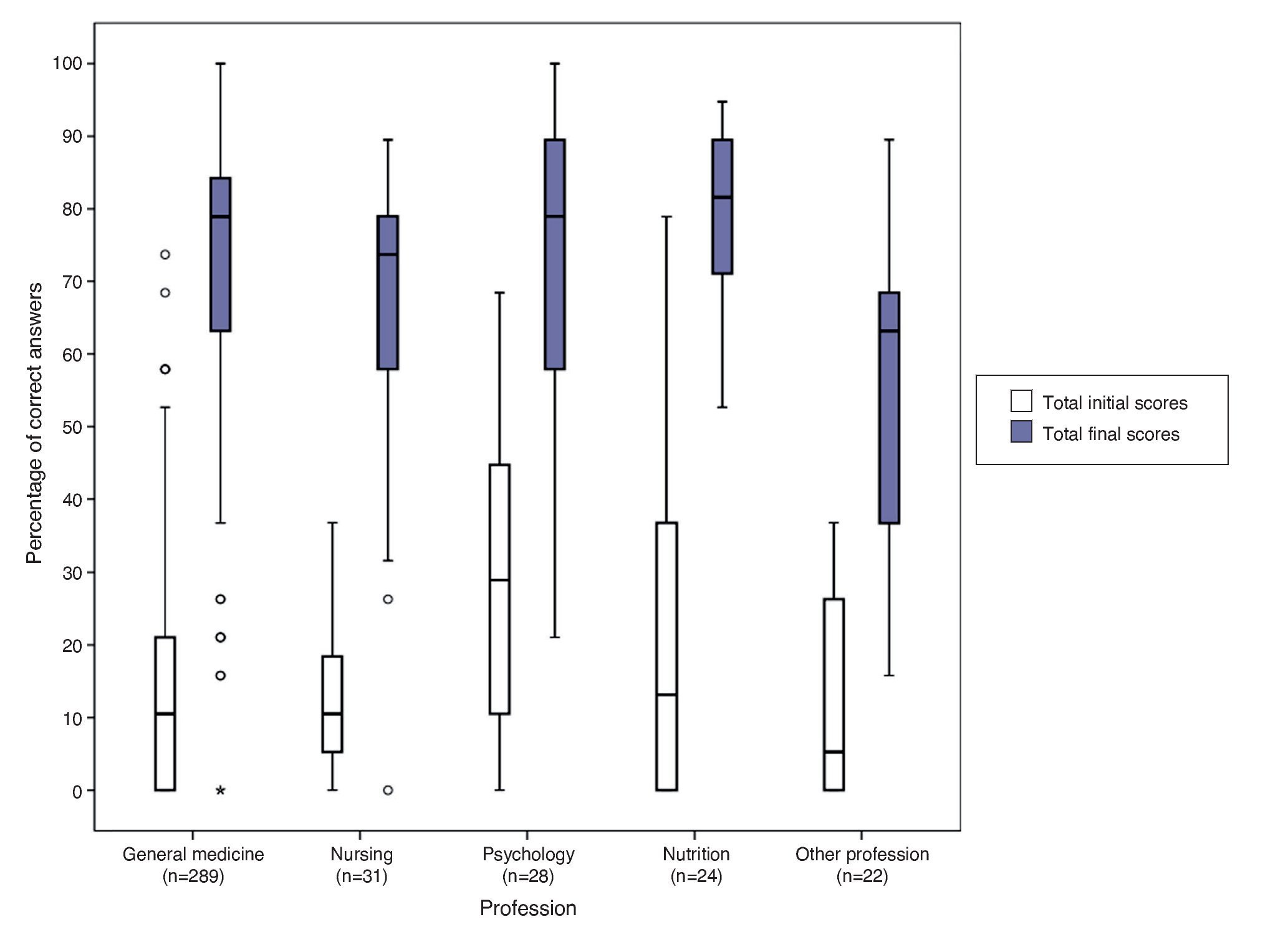

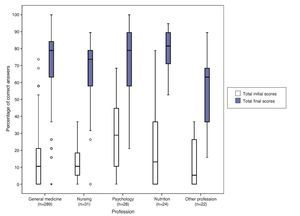

A highly significant difference was found for all participants (p <0.0001) between the median of the overall result in the initial evaluation (10.5; IQR 0.0-26.3) and the final evaluation (73.7; IQR 63.2-84.2). Figure 1 shows the distribution of the overall result (percentage of total correct answers) in the initial and final evaluation of the participants by type of profession. In the initial evaluation 64.9% (n=256) obtained a score <20.0, which decreased to 1.8% (n=7) in the final evaluation. In the initial evaluation 1.8% (n=7) passed (with >60% of correct responses compared with 75.1%, n=296) in the final evaluation. There were no significant differences found by gender in the percentage of participants approved (p=0.076), but there were differences by state associated with the difference in their professional profile.

Figure 1 Comparison of the result in the initial and final score of the complete application course of the Child Development Evaluation (CDE) test by type of profession.

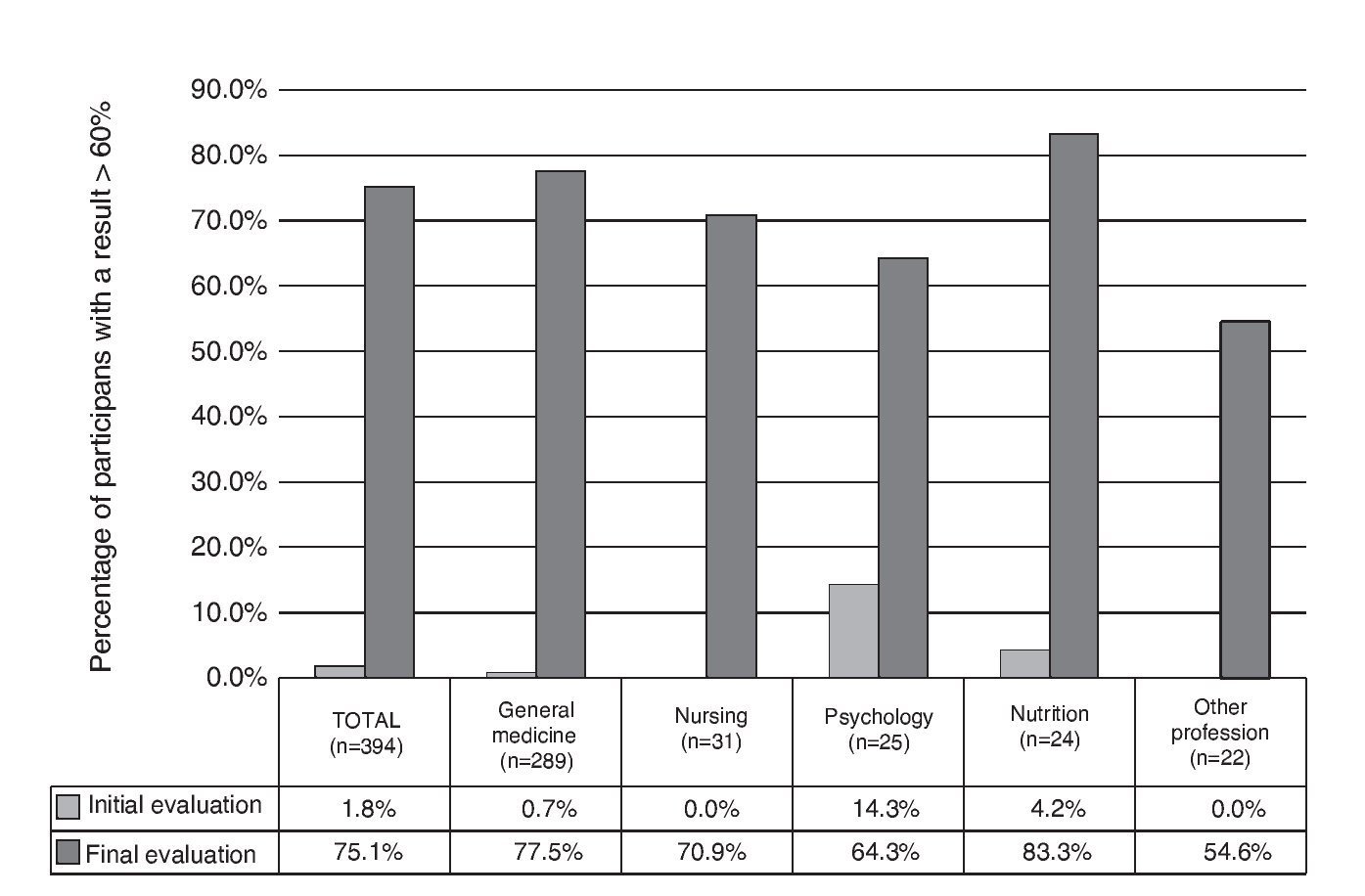

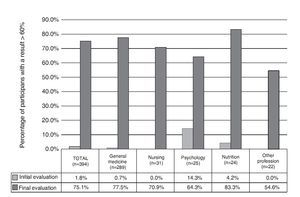

According to type of profession, in the initial evaluation 14.3% of psychology professionals followed by 4.2% of nutrition professionals and 0.7% of general medicine physicians passed. No participants from nursing or other professions passed this evaluation. In the final evaluation the highest percentages of test approval were for nutrition (83.3%) followed by general medicine (77.5%), nursing (70.9%) and psychology (64.3%). The lower proportion of approved participants (54.6%) was for other professions (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Comparison of the percentage of participants who passed the initial and final training course evaluations by type of profession.

3.2. Result of the final evaluation by question

A percentage of correct answers >75% was obtained in ten questions, which referred to the general structure of the test, axis and areas of evaluation and aspects of the application (Table 1). The questions with the lower percentage of correct responses (43.4–63.7%) were those related to the score of the test (questions 5, 16, 21, 22, 23 and 25) and the conceptual questions about development and what is a screening test (questions 1, 19 and 20).

4. Discussion

The results of the study showed that the proposed model of training had a positive and significant impact on the acquisition of knowledge on the CDE test on the personnel who work in primary care. The difference in the number of participants in each course was not associated with differences in the percentage of personnel who passed (86.1% in the course with the greater number of participants and 67.1% on average in the rest of the courses with <50 participants), which can be explained by maintaining a 25:1 ratio (25 participants per facilitator).

The results of the initial evaluation highlight the lack of knowledge of the participants, which can be explained by not reading the manuals before the class17,18 because the percentage of initial approval was 1.8%, and 64.9% had a score <20% in this evaluation.

Although the psychology and nutrition participants were those who obtained the highest percentages of approval in the initial evaluation, in the subsequent evaluation there were significant differences only with the staff of other professions. Differences found by state are explained by the professional profile of the participants. The profession with the biggest gain in knowledge was general medicine, which is in agreement with the recommendations that the ideal would be for the physician to administer the CDE test during healthy child consultations16. However, given the results of this study, this test can be applied by nursing, psychology, and nutrition personnel who have already passed the training course.

The methodology described allows assessment of the level of knowledge acquired through the course and generation of recommendations and counseling to enhance knowledge in persons with low scores. One limitation of this study is that the criteria of passing the course does not guarantee a correct field application. It is necessary to design a model of supervision of the application of the field test to verify its correct application.

The training model is suitable for acquisition of general knowledge about the test. To improve the overall results, future training is required that will reinforce the themes of general concepts about child development, qualification, and interpretation of results, and will instruct participants to read the supporting materials prior to the course. To ensure that meaningful learning has been achieved, translated as a correct evaluation of child development in primary care, it is necessary to supervise the correct application of the CDE test by already-trained staff.

Ethical disclosure

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Funding

This study was carried out with financing provided by the Convenio CPSS/ART.1°/023/2013, between Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez and the Comisión Nacional de Protección Social en Salud (CNPSS).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

To personnel of the Régimen Estatal de Protección Social en Salud, Coordinaciones Estatales de PROSPERA as well as to the psychologists and responsible persons from the Estrategia de Desarrollo Infantil (PROSPERA) and to personnel of the Programa de Atención a la Salud de la Infancia y Adolescencia of Baja California Sur, Chiapas, Jalisco, Querétaro, Sinaloa and Tlaxcala; to personnel of the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez (Marta Lia Pirola, Jessica Guadarrama Orozco, Mariel Pizarro Castellanos, Guillermo Vargas López, Guillermo Buenrostro Márquez, Elías Hernández Ramírez, Ana Alicia Jiménez Burgos, Rocío del Carmen Córdoba García, Socorro De la Torre); to personnel of CeNSIA (Ignacio Villaseñor Ruíz, Verónica Carrión Falcón, José de Jesús Méndez de Lira, Diana Araujo, María Magdalena Solares Llamas); to Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (Caridad Araujo, Ricardo Pérez Cuevas) and to the Coordinación Nacional de PROSPERA Programa de Inclusión Social (Paula Angélica Hernández Olmos, Hugo Erick Zertuche Guerrero).

Received 21 October 2015;

accepted 22 October 2015

* Corresponding author.

E-mail:antoniorizzoli@gmail.com (A. Rizzoli-Córdoba).