Introducción: En los últimos años se han desarrollado varias pruebas de tamiz para el desarrollo infantil temprano (DIT) en menores de 5 años en México. El objetivo de esta revisión fue comparar la calidad del reporte de validación publicado y riesgo de sesgo entre diferentes pruebas desarrolladas y validadas en México.

Métodos: Se realizó una búsqueda en bases de datos, literatura gris y referencia cruzada documental. Se efectuó un análisis comparativo de la calidad del reporte (STARD) y el riesgo de sesgo (QUADAS y QUADAS-2).

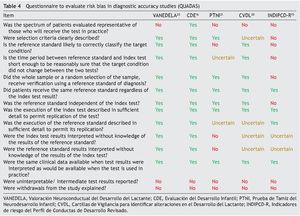

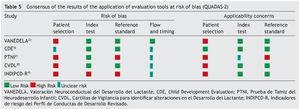

Resultados: Se incluyeron las siguientes cinco pruebas: Valoración Neuroconductual del Desarrollo del Lactante (VANEDELA), Evaluación del Desarrollo Infantil (EDI), Prueba de Tamiz del Neurodesarrollo Infantil (PTNI), Cartillas de Vigilancia para identificar alteraciones en el Desarrollo del Lactante (CVDL) e Indicadores de riesgo del Perfil de Conductas de Desarrollo (INDIPCD-R). Ninguna cumplió el 100% de los ítems de acuerdo con STARD. Las más completasen su descripción fueron VANEDELA y EDI. El área de procedimientos de muestreo fue en la que hubo menor cumplimiento (VANEDELA, PTNI, CVDL, INDIPCD-R). En QUADAS, todas las pruebas presentaron algún riesgo de sesgo. Las más importantes fueron la selección de la muestra y la elección del estándar de oro, que en dos estudios se identificó que no era el más adecuado (PTNI, INDIPCD-R).

Conclusiones: Las pruebas de tamiz mexicanas para el DIT varían en la calidad de reporte publicado y riesgo de sesgo. La de mejor calidad de reporte de validación es VANEDELA y la de menor riesgo de sesgo en los datos publicados es la prueba EDI.

Background: In recent years a number of child development screening tools have been developed in Mexico; however, their properties have not been compared. The objective of this review was to compare the report quality and risk bias of the screening tools developed and validated in Mexico in their published versions.

Methods: A search was conducted in databases, gray literature and cross references. The resultant tests were compared and analyzed using STARD, QUADAS and QUADAS-2 criteria.

Results: “VAloración NEuroconductual del DEsarrollo del LActante” (VANEDELA), “Evaluación del Desarrollo Infantil or EDI” (CDE in English), “Prueba de Tamiz del Neurodesarrollo Infantil” (PTNI), “Cartillas de Vigilancia para identificar alteraciones en el Desarrollo del Lactante” (CVDL) and “Indicadores de riesgo del Perfil de Conductas de Desarrollo” (INDIPCD-R) were included for comparison. No test fulfilled all STARD items. The most complete in their methodological description were VANEDELA and CDE. The areas lacking more data on the reports were recruiting and patient selection (VANEDELA, PTNI, CVDL, INDIPCD-R). In QUADAS evaluation, all had some risk bias, but some serious concerns of risk bias were raised by patient sampling and by the choice of the gold standard in two tests (PTNI, INDIPCD-R).

Conclusions: Child development screening tests created and validated in Mexico have variable report quality and risk bias. The test with the best validation report quality is VANEDELA and the one with the lowest risk bias is CDE.

1. Introduction

Early identification of alterations in child development is essential to the well-being of children and their families because it allows providing an accurate diagnosis and implementing an early intervention for those having some type of alterations.1 For the children who receive them, such interventions are associated with better adulthood functionality at multiple spheres2 in addition to having a very high cost-benefit ratio.3

The comparison of clinical characteristics of each test is important to assist in the selection of the most appropriate tool for development evaluation. Moreover, it is essential to compare their quality of report and risk of bias because biased reports of diagnostic or screening tests results may end in the widespread adoption of tools that produce an inaccurate risk classification, thereby leading medical personnel to make an incorrect referral, diagnosis or treatment decision.4

A systematic review and comparative analysis of the literature done in 2012 by Romo-Pardo et al. found 13 screening tests that were created and validated in America for the timely identification of problems related to child development, but none of them with data published for the Mexican population in scientific journals (except Denver-II).4 In recent years a significant number of screening tests have been created, some of which are already being applied to children <5 years of age in Mexico. This information on the validation and properties is not found in indexed journals, and a comparison has not been made between them.

Based on the above, the aim of this paper was to compare the quality of the validation reports published and their risk of bias among the screening tests developed and validated in Mexico.

2. Methods

2.1. Search and analysis

Because part of the information about the tests created in Mexico is not available in search engines of scientific journals, during October 2015 an exhaustive search was carried out for child development screening tools in children <5 years of age, designed and validated in Mexico from 1980 to date. A simple strategy was carried out using the Spanish terms “neurodesarrollo” or “desarrollo infantil” and “tamizaje” as well as the English terms “child development” and “screening”, in PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web Of Science, EMBASE, EBSCO, Google Scholar, LiLACS and SciELO, limiting the results to tests elaborated in Mexico.

Through different search strategies, cross references and asking experts in the field, seven screening tests created in Mexico for neurodevelopment evaluation were identified. Using the name of the tests, a new exhaustive search was performed looking for reports of their validation. The gray literature was screened in addition to the previously consulted sources. For the analysis only those where a published validation report was found were included, excluding the remaining reports.

2.2. Tools used for evaluation

2.2.1. STARD

The Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD)5,6 were designed with the objective of improving the quality of the reports of diagnostic accuracy studies. They consist of a checklist of 25 items and flow diagrams that report the patient selection methods, the order in which the tests are conducted and the number of patients that should be evaluated with the index test and reference standard. They evaluate if the publications provide sufficient information that would allow detecting potential study bias and evaluate the potential generalization and applicability of the results.

2.2.2. QUADAS

The “Quality Assessment of Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy in Systematized Reviews” tool (QUADAS)7 was developed to assist in the evaluation of risk of bias in publications of diagnostic accuracy. It was elaborated based on three reviews of existing literature by using a Delphi methodology procedure, with the participation of a group of nine experts. It is composed of checklist of 14 qualitative items, which includes: patient spectrum characteristics of the sample, bias in disease progression, bias of verification, bias of review, bias of clinical review, bias of incorporation, how the test was done and how indeterminate results are managed. These items should be scored with the response “yes” if it is believed that the study being analyzed meets the characteristics described in each item; “no” if it does not meet the characteristics, or “unclear” if the test does not contain sufficient information to make a judgment.

2.2.3. QUADAS-2

The QUADAS-28 tool was designed with the objective of evaluating the risk of bias in the studies of diagnostic accuracy. It is a structured questionnaire with open questions grouped in four domains, which include patient selection, index test, reference standard, and time elapsed between the index test and reference standard. The tool should be completed in four stages: the first intends to establish a review question; the second, to develop a specific guide for review; subsequently, evaluate the flow diagram published or, in case it has not been published, create one with the data provided and, finally, establish a judgment about bias and applicability. Each domain is evaluated in terms of risk of bias, and the first three are also evaluated in terms of applicability concerns. To aid in establishing a decision on the risk of bias, some signal questions were included. This tool allows the evaluators to create a tabular presentation for each study evaluated, classifying each item as low risk, high risk or unclear risk.

2.3. Evaluation procedure

The analysis was performed in stages. In the first stage, each of the authors evaluated, separately and independently, the quality of the validation report using the STARD6 tool, and the risk of study bias with the QUADAS7 and QUADAS-28 tools. The results of this evaluation, including flow diagrams and checklists, were collected using the formats developed for each tool. In the second stage, the evaluation formats from each of the authors were compared. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. A final evaluation was produced, which was then transferred to the aforementioned formats and transformed for its graphic presentation.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of the screening tests

Seven screening tests of neurodevelopmental alterations created in Mexico were identified; Scale for Integral Child Development (Escala de Desarrollo Integral del Niño)9, Evaluation of the Neurodevelopment of the Newborn (Evaluación del Neurodesarrollo del Neonato, EVANENE),10 Neurobehavioral Evaluation of the Newborn (Valoración Neuroconductual del Desarrollo del Lactante, VANEDELA),11 Child Development Evaluation (CDE) (Evaluación del Desarrollo Infantil, EDI),12 Screening Test for Child Neurodevelopment (Prueba de Tamiz del Neurodesarrollo Infantil, PTNI),13 Surveillance Manuals to identify changes in Child Development (Cartillas de Vigilancia para identificar alteraciones en el Desarrollo del Lactante, CVDL)14 and Indicators of the Risk Profile of Behaviors in Development (Indicadores de Riesgo del Perfil de Conductas de Desarrollo, INDIPCD-R).15 All publications found using the scientific search engines were related with the CDE test16-18 with the exception of one related with NPED (Neuropediatric Development),19 which was excluded because it evaluated a developmental tool created in Cuba and had no concurrent design validation. The remainder of the tests were located in non-indexed scientific publications (INDIPCD-R15, CVDL20), accessed through web pages (PTNI21), or as books, manuals, institutional research protocols or as masters/doctoral thesis (EVANENE22, VANEDELA23, CDE16-18, PTNI21). Three had published validation articles in scientific journals, one had the validation data published online and another as a thesis report. Finally, five tests were included for evaluation. Excluded from this study were the Scale for Integral Child Development because no validation data were found, and EVANENE for the same reason because only a thesis of its validation was found, but doing so as an instrument for screening for brain damage.

3.2. General characteristics of the tests evaluated

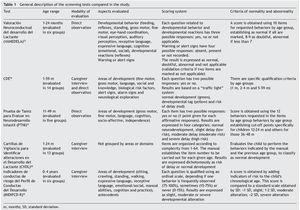

The general characteristics of the tests evaluated are described in Table 1. A large variation in the age ranges evaluated was found. CDE is the test that evaluates the broadest age range (1-59 months). Most of the tests use direct observation as the only modality for evaluation except for the CDE, which has a mixed evaluation modality: direct observation/caregiver structured interview. None of the tests uses paper-based home interview as an exclusive modality, e.g., filling out a questionnaire by the parents. The areas evaluated show a large variability although they generally adjust to the areas recommended in the literature: motor, language, adaptive or cognitive, personal or social.24,25

Only INDIPAD-ETS and VANEDELA present the evaluation of neurological signs. The rating systems used differ widely but are adequately described. The same can be said of the criteria for abnormality except for the INDIPCD-R, whose published definition is confusing as it is unclear how the score obtained is compared with the gold standard. The properties of the screening tests reported in validation studies reviewed are summarized in Table 2.

The sample sizes used for the validations varied. The largest one was reported for the PTNI. The sample selection also varied as two tests were validated in populations selected from health institutions (VANEDELA and INDIPCDR), two obtained their samples in specific populations (PTNI in rural and CVDL in urban) and only one presented a sample selection procedure intentionally balanced in terms of demographic characteristics and biological risk factors (CDE).

The gold standard used in the validation was also different for the different tests; three used a neurodiagnostic test such as the Gesell Developmental Schedules (GDS)26 or Battelle-2 Developmental Inventory (BDI-2)27 (VANEDELA, CDE, CVDL). One test used the diagnostic test from which (PCD-R) itself derives.28,29 Another test used as a proxy indicator a series of measures of the nutritional status, anemia and growth, alone and as composite scores (PTNI).

All tests reported sensitivity and specificity values as well as positive predictive values (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) that were adequate with what is recommended in the literature,24 although there were tests that had a wide variation depending on the age group evaluated (VANEDELA) or the gold standard used (PTNI). In some age ranges they were too low to be used. Three tests did not describe the confidence intervals of their reported data. (VANEDELA, PTNI, CVDL).

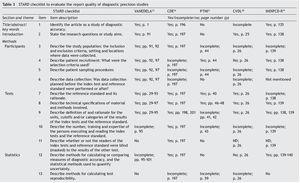

3.3. Results of the evaluation of the quality of the report

Table 3 shows the checklist of the STARD tool. None of the tests evaluated complied with the entirety of the items to be reported. The most complete in their description were VANEDELA and CDE. The areas in which most tests were found with missing or incomplete information were those that refer to the description of the sampling procedure and selection of patients (VANEDELA, PTNI, CVDL, INDIPCD-R), the methods by which the missing data and the cases lost to follow-up were handled (All), description of the participants and the study flow diagram (PTNI, CVDL, INDIPCD-R, CDE) and the methods established for measuring the reproducibility of the test (INDIPCD-R).

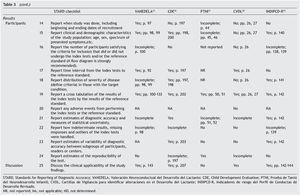

3.4. Results of the evaluation of the risk of bias

Table 4 shows the results of the application of the tool for evaluation of the risk of bias QUADAS. None of the tests met 100% of the criteria evaluated. Only one test evaluated a spectrum of patients representative of the population (CDE). None reported management of the uninterpreted results, abandonment of the study or other case losses. Results of the QUADAS-2 evaluation are shown in Table 5 and are a final qualitative evaluation representing a consensus of the authors’ opinion on how much risk of bias each tests presents. Because of its validation using a proxy gold standard, the PTNI presents a high risk of bias with respect to the standard of reference (weight for age, height for age, anemia and early stimulation not independent to the test).

The INDIPCD-R presents a high risk of bias of its index test and gold standard because it is validated against itself. Because they are samples by convenience without any type of adjustment, all tests have a high risk of bias with respect to patient selection. The one with the least risk was the CDE because it intentionally balanced all the groups evaluated.

4. Discussion

In previous reviews4 and reports,14,15 the comment about the few or no mentions of Mexican tests in the literature is repetitive as well as how difficult it is to find the validation of Latin American tests. The small number of results obtained when performing simple searches, limiting the results to Mexico, could be explained by two factors: the first would be the low level of visibility of Latin American journals because many are not indexed and therefore do not appear in search engines.30 The second, due to a mix between a probable “fear” of international publications and a “malinchismo” effect towards national publications,31 which makes harder to take the decision to begin the laborious process of transforming the text of the thesis into scientific articles.32

Because there is no ideal screening test for child development, it can be said that the general characteristics of all tests evaluated make them adequate for their use in Mexico. Before considering aspects on the quality of their validation, the decision to use one over the other should take into account its flexibility to be used.24 In this regard, age ranges evaluated, variety in evaluation modalities and simplicity of the visual “traffic light” rating system favor the CDE test.

No study is found to be free of defects in the quality of its report. The most complete was the VANEDELA report, which is very broad and complete because it is published as a 180 page thesis. Although almost all data required by STARD for evaluating the reliability of the data are found, there are aspects of the methodology that limit its external validity such as the small sample size of each of the age groups evaluated and the process of sample recruitment, which was done by convenience in an urban population from clinical/ hospital environments. Other validation reports such as the INDIPCD-R omit important data that may help to assess its validity, which makes its objective evaluation difficult. One possible solution for this phenomenon could be to extend the use of the evaluation tools mentioned in this article and use them as a guideline checklist to guarantee that the scientific papers are complete prior to publication.33

There is no bias-free scientific publication; however, there are procedures to reduce bias. The results of the two final evaluations (QUADAS and QUADAS-2) demonstrate that although the data of sensitivity and specificity are grossly similar among the tests compared, the validity of these data is compromised to varying degrees. Some of the publications evaluated omit basic data such as the measures of dispersion or precision of the measurement, and others compromise the concurrent validation procedure by comparing the index test against itself or to a proxy measurement. Other tests such as VANEDELA also have a high risk of bias due to the small subsample size.

Similar to the conclusions in comparative reviews of developmental screening tests performed in other parts of the world,34 it was found that among the tests for neurodevelopmental screening created in Mexico, none is perfect. The most flexible in its application and with less risk of bias in its validation results was the CDE test.

The tests for child development, created and validated in Mexico are, in general, adequate for their use in the local context although they have variable qualities of published reports and bias risks, and none is perfect. The test with the best validation report quality is VANEDELA followed by CDE, and the one with the lowest risk of bias in the data published is the CDE test. A comparative study of the screening tests vs. the gold standard will be required in order to establish which has the best properties.

Funding

No external funding was used for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the collaboration of Lic. Josué Laguna Hernández, Sección de Archivo Histórico, Biblioteca Dr. Ramón Villarreal Pérez, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Xochimilco, in the localization of one of the tests evaluated in this study.

Received 2 November 2015;

accepted 3 November 2015

* Corresponding author.

E-mail:rodrigo_aquilino.orcajo_castelan@kcl.ac.uk (R. Orcajo-Castelán).