Liver cancer (LC) has become the world’s sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths [1,2]. With the development of surgical, local ablative and intra-arterial techniques, immunotherapy, and targeted therapies [3], and liver-protecting drugs [4], great progress has been made for the treatment of LC in the past 5 years [3,5]. However, the burden of disease and death is still heavy and faces severe challenges. The burden of chronic liver diseases is significant, the increasing burden of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) [6]. Additionally, the number of ALD-related HCC cases in the United States is higher, which may offset the decline in virus-related LC [1]. LC incidence continues to increase in women by about 2 % per year, and its mortality continued to increase in women by 1 % per year from 2013 to 2021 [1,7]. The incidence of LC has shifted from patients with virus-related liver diseases to those with non-viral causes, including ALD and NAFLD, especially in high-income countries [1,6].

Among known etiologies, HBV or HCV infections have been the leading causes of death from LC [8], accounting for nearly 70 % of all LC deaths, along with alcohol consumption, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and other causes [9]. Since the discovery of the HBV in 1965, significant progress has been made in prevention efforts, including the widespread implementation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination programs and the development of nucleotide analogues (NAs), but there has been little success in achieving a cure [10]. In recent years, the application of direct-acting antiviral drugs (DAAs) has brought revolutionary changes to the treatment of hepatitis C [11]. In particular, Epclusa, through standardized short-term oral medication, over 95 % of hepatitis C patients can be completely cured [12]. However, hepatitis virus-related LC still accounts for a large proportion of LC deaths [8]. The number of HBV-related LC (LCB) is higher in China, South Korea, India, Japan, and Thailand, while the number of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related LC (LCC) is higher in China, Japan, and the United States. It is important to comprehensively estimate the global LC and hepatitis virus-associated LC mortality burden to evaluate the progress of international LC management and treatment goals and to provide targeted interventions. The core advantage of this study lies in quantifying the global distribution characteristics of liver cancer. This data is crucial for resource allocation, precisely identifying high-risk populations and regions, guiding the distribution of vaccines, updates to the WHO essential drug list, antiviral treatment plans, and precise resource allocation for food safety supervision, thereby eliminating health inequalities.

This annual update of the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study provides an opportunity to track disease control at the country, regional, and global levels, contributing to health decision making and the balanced allocation of health resources. Previous study has evaluated the global mortality of chronic liver diseases attributable to HBV and HCV from 1990 to 2019 [13]. Although previous studies, including the analysis of the GBD project, have extensively investigated the trends in the burden of hepatitis virus-associated LC, most studies have focused on historical patterns [14] or predictions of future overall mortality [13,15]. In addition to the basic estimates of mortality, there is an urgent need to reveal more specific and detailed insights, such as the rate of change in mortality of hepatitis virus-associated LC, how much space for improvement different countries have in reducing the burden of death, and the role of non-epidemiological factors such as age structure in exacerbating the impact of the disease. Revealing information at these levels is crucial for understanding regional health inequalities and identifying populations that may require priority attention. To date, the comprehensive assessment of hepatitis virus-associated LC mortality remains lacking. The mortality burden of LC varies in different parts of the world [16], an updated assessment is needed to support the management of LC and precise implementation of strategies to reduce the global mortality burden. Despite recent advancements, mortality remains high, with worsening inter-regional disparities. Based on the GBD 2021 data, this study provides an estimate of the total LC and hepatitis virus-associated LC temporally and spatially by sex, region, and country and forecasts it to 2050 by the Bayesian age-period-cohort (BAPC) method.

2Materials and Methods2.1Study population and designWe extracted data on deaths and age-standardized mortality rates (ASMRs) and their 95 % uncertainty intervals (UIs) for LC, LCB, and LCC from the GBD Study 2021, which includes six World Health Organization regions (Southeast Asia, Americas, Europe, Western Pacific, Africa, and Eastern Mediterranean), five sociodemographic index (SDI) quintiles, and 204 countries and territories. Additionally, demographic estimates for the global and 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2021, as well as demographic projections from 2021 to 2050, were obtained from the GBD database. Demographic projections for the six regions were sourced from the World Population Prospects 2024 Revision by the United Nations. These demographic data, along with mortality data during 1990–2021, were used to forecast deaths and ASMRs up to 2050.

The methodology used in this study followed the general analytical framework of the GBD 2021 study, which used 71 statistical modeling techniques, have been described elsewhere [17]. Furthermore, we used multiple analytical models, including the Bayesian age-period-cohort (BAPC) model, average annual percent change (AAPC), Bayesian spatiotemporal model, decomposition analysis, and frontier analysis, to evaluate and predict the spatial–temporal trends of LC, LCB, and LCC deaths and ASMR in different regions, SDI quintiles, age, and sex. All the detailed methods and computational formulas used in this study were described in the Supplementary Methods.

2.2Statistical analysesThe BAPC models incorporate age, period, and cohort effects as covariates to predict ASMRs and mortality for LC, LCB, and LCC from 2022 to 2050, based on historical age-stratified death data and population. It assumes that deaths in different age groups each year follows a Poisson distribution. Each effect adopts a second-order random walk prior, and a log-linear model is used to fit the relationship between deaths and effects. These predictions reveal future trends in death burden of LC, which serve as the basis for further analyses. The AAPC was calculated using Joinpoint software to measure the average temporal change of ASMR. The Bayesian spatiotemporal model fits the relationship between ASMR of 204 countries/territories and spatial effects, temporal effects, and spatio-temporal interaction effects. It reflects cross-country differences from a spatial perspective and enables the comparison of dynamic trends in ASMR across different periods. The spatial effect S[i] represents the ASMR of the ith country or territory in the specified time range relative to the global average α. Frontier analysis was conducted to evaluate the minimum achievable ASMR of LC, LCB, and LCC in each country or territory by 2050 and its potential space for ASMR improvement in 2050. The SDI was adopted as an indicator to determine the development level of a country or territory, which ranges from 0 (lowest development) to 1 (maximum development). SDI values by country or region are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The SDI is used as an indicator to measure the development level of a country, and the free disposal hull (FDH) model is used to establish the frontier. This method constructed the distribution of the empirical efficiency frontier by identifying the lowest observed ASMR in the SDI range, and calculated the difference between the predicted ASMR in 2050 and the frontier mean as the effective difference (ED). The greater the ED, the greater the space for improvement in reducing ASMR of LC. Finally, we used the decomposition methodology of Das Gupta to decompose the change in deaths over a period of time by population age structure, population growth, and epidemiological changes. The methods used by the GBD database to address missing data issues and eliminate component biases in the final estimation results have been fully described in the GBD research [18]. Further details and formulas of the above methods are presented in the Supplementary Methods.

2.3Ethical statementThis study used publicly available, aggregate, de-identified data (GBD 2021; UN WPP 2024); no human participants or identifiable data were involved, so IRB approval and informed consent were not required. Consent for publication: Not applicable.

3Results3.1Deaths from LC, LCB, and LCC in different regions, 1990–2021From 1990 to 2021, global deaths from LC doubled from 238,969 in 1990 to 483,875 in 2021 (Supplementary Table 2–4), including LCB and LCC, which increased by 70.11 % and 128.48 %, respectively. Hepatitis virus-related LC accounted for 70 % of LC-related mortality, with 40 % from HBV and 30 % from HCV. Asia accounts for the majority of LC-related deaths globally, including 70 % from LC, 80 % from LCB, and 60 % from LCC. The ASMRs of LC and LCC were highest in Africa during 1990–2021. For men, Asia had the highest ASMR from 1990 to 2021.

The highest death rates and ASMRs for LC and LCB were observed in the middle SDI quintile (Supplementary Table 5), but the highest ASMR of LC among women was seen in the low SDI quintile. In 2021, the highest ASMR of LCB among women was in the low SDI quintile. Asia had the highest ASMR for LCB, while Africa had the highest ASMRs for LCB and LCC among women. The low SDI quintile had the highest ASMR of LCC. Overall, the high SDI quintile had the highest deaths and ASMR of LCC for both men and women.

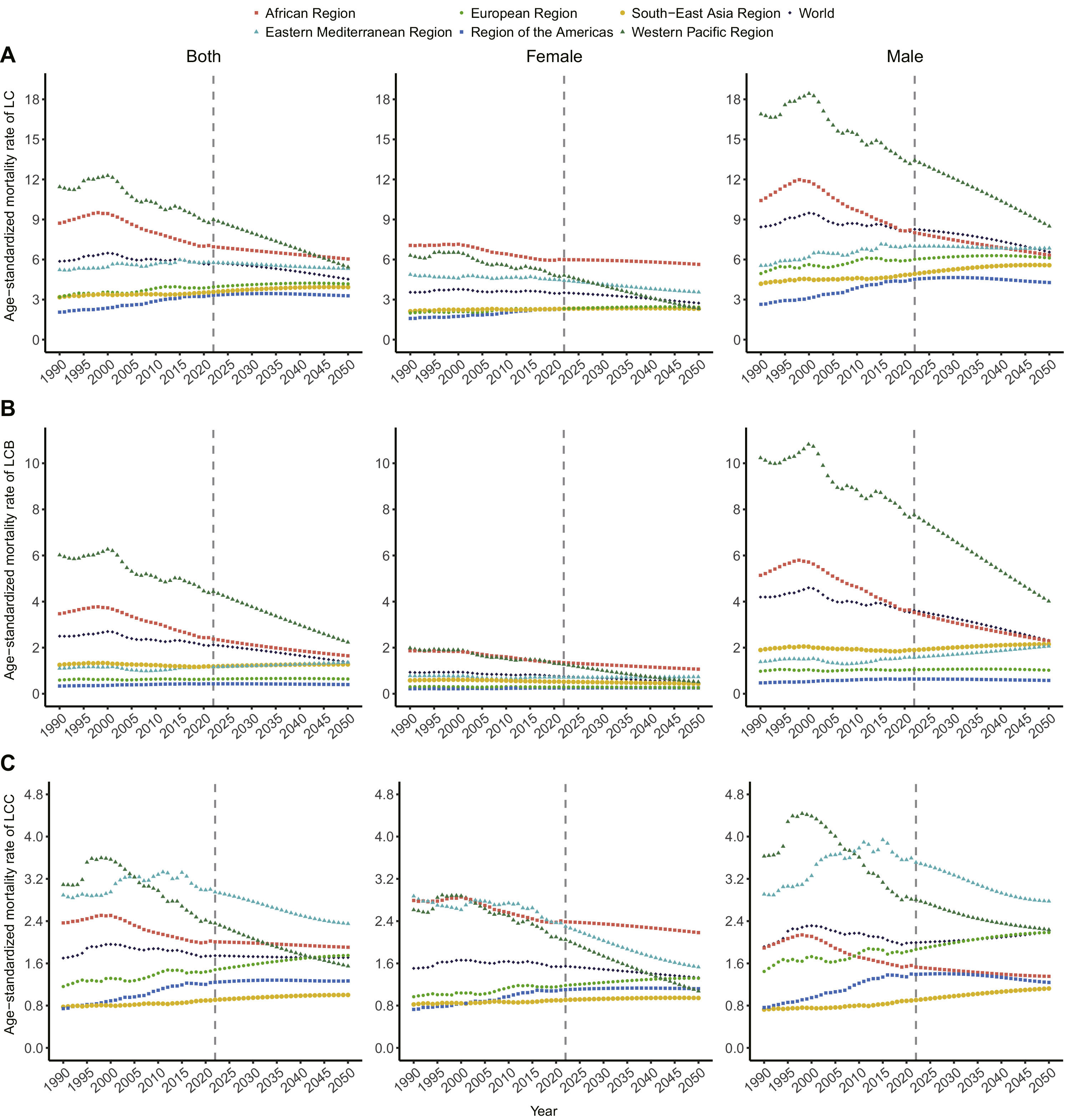

3.2ASMRs and AAPCs for LC, LCB, and LCC from 1990 to 2050, by sex and regionDuring 1990–2021, the global ASMR of LC was stable (AAPC=–0.11, 95 % CI:0.35 to 0.12; Fig 1a), with a predicted decline until 2050 (AAPC=–0.34, 95 % CI:0.46 to –0.23). The ASMR for men remained higher than for women, especially for LCB. The global ASMR of LCB decreased during 1990–2021 (AAPC=–0.54, 95 % CI:0.81 to 0.27; Fig 1b), with continued decline expected until 2050 (AAPC=–0.94, 95 % CI:1.12 to –0.77). The LCC ASMR was stable during 1990–2021 (AAPC=0.05, 95 % CI:0.26 to 0.36; Fig 1c). The WPR had the highest ASMR for LC, though it showed the fastest decrease in ASMR (AAPC1990–2021=–0.87, AAPC1990–2050=–1.01). The Americas had the lowest ASMR but the highest increase in ASMR (AAPC1990–2021=1.56, AAPC1990–2050=1.03). For LCB, the WPR consistently had the highest ASMR (ASMR1990=6.02, ASMR2021=4.38), while the Americas had the lowest ASMR, with the fastest increase, especially among men. For women, Africa had the highest ASMR for LC, while the Americas had the lowest ASMR. The highest ASMR of LCB among women shifted from the WPR in 1990 to Africa in 2021. For LCC, the largest increase in ASMR occurred in the Americas (AAPC=1.58, 95 % CI: 1.29–1.87), and the fastest decline was in the WPR (AAPC=–0.88, 95 % CI:1.33 to –0.43). The highest ASMR for LCC shifted from the WPR (ASMR=3.09) to the Eastern Mediterranean (ASMR=3) during 1990–2021.

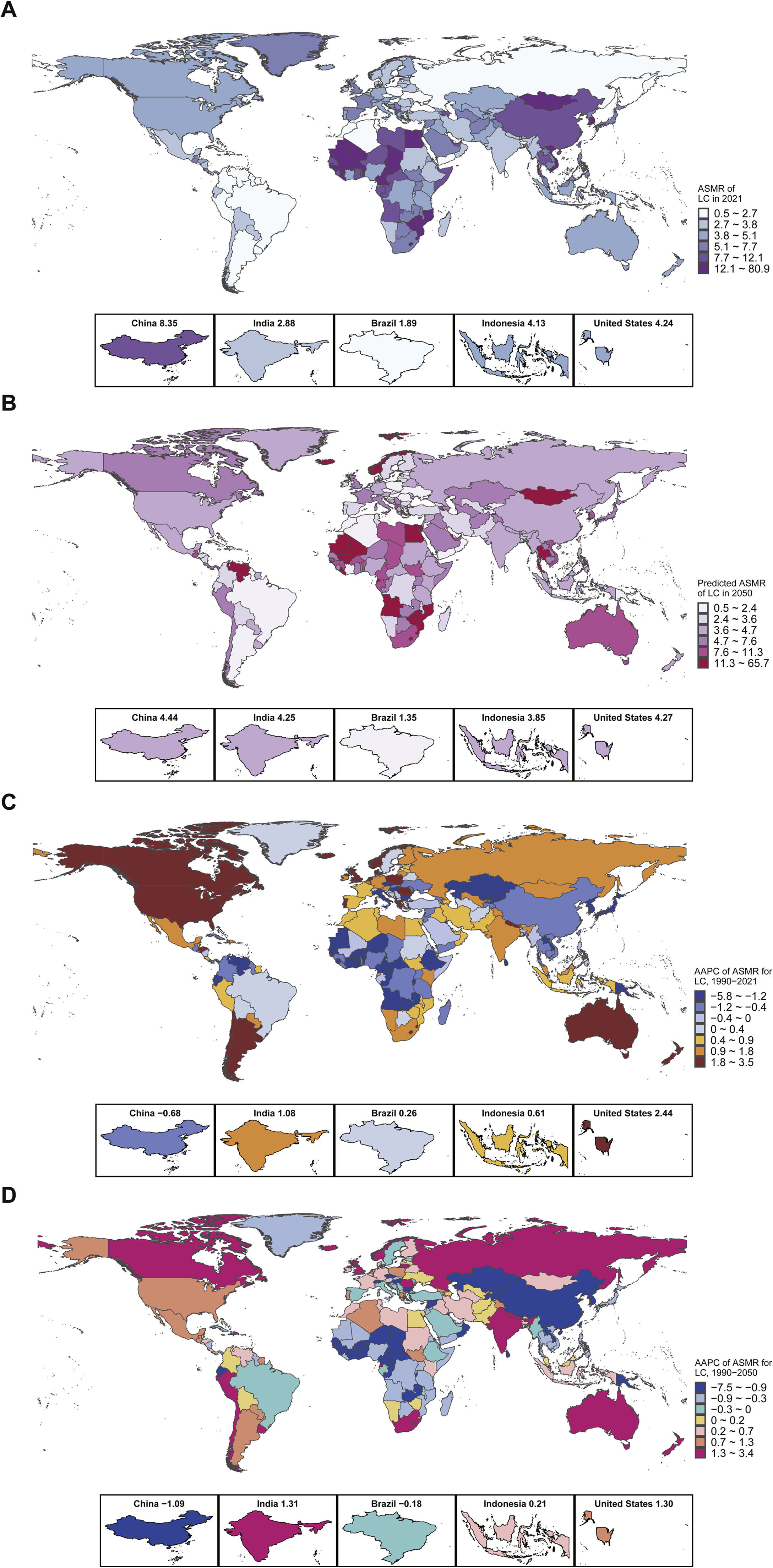

3.3ASMR, AAPC, and frontier analysis in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2050Geographical differences in LC ASMR were significant, with Mongolia consistently having the highest ASMR for all types of LC between 1990 and 2021 (Fig 2a–b). Mauritius showed the fastest decrease in ASMR during 1990–2021 (AAPC=–5.70, 95 % CI:9.51 to –1.74), while Australia saw the fastest increase (AAPC=3.41, 95 % CI: 2.82 to 4.00). By 2050, LC ASMR is expected to decrease the fastest in Mauritius (AAPC=–7.31, 95 % CI:8.86 to –5.74) and increase most rapidly in Norway (AAPC=3.31, 95 % CI: 2.66 to 3.96). Among the five most populated countries, the fastest increase in LC ASMR occurred in the United States (AAPC=2.44, 95 % CI: 2.09 to 2.78, Fig 2c–d), with the ASMR in China only decreasing (AAPC=–0.68, 95 % CI:1.25 to –0.10). By 2050, the ASMR of LC is expected to decrease the fastest in China (AAPC=–1.09, 95 % CI:1.34 to –0.85), while India will see the fastest increase (AAPC=1.31, 95 % CI: 1.13 to 1.50, Supplementary Table 6). LCB ASMR will decrease the fastest in Kuwait (AAPC=–3.19, 95 % CI:4.85 to –1.50, Supplementary Table 7), while Saint Kitts and Nevis will see the fastest increase (AAPC=2.44, 95 % CI: 2.00 to 2.88; Supplementary Fig 1). For LCC, the fastest decrease occurred in Bulgaria, and the fastest increase occurred in Lesotho (AAPC=3.26, 95 % CI: 2.99 to 3.53) during 1990–2021. By 2050, LCC is expected to decrease the fastest in Singapore (AAPC=–3.58, 95 % CI:4.01 to –3.15, Supplementary Table 8) and increase the fastest in Australia (AAPC=3.30, 95 % CI: 3.07 to 3.53; Supplementary Fig 2). By 2050, LC, LCB, and LCC ASMRs will be highest in Mongolia and Gambia. Irrespective of etiology, among the top 10 effective differences, most countries fall within middle- and high-SDI groups worldwide. The ASMRs of LC in Mongolia, Gambia, and Mauritania have great room for improvement (Fig 3). Among the five most populated countries in the world, Indonesia, India, China, and the United States have large differences in ASMR of LC, and Brazil has achieved the lowest ASMR for all causes of LC. Regardless of the etiology, the effective difference of ASMR in Somalia, Burundi, Haiti, Hungary, Niger, and other countries was 0, indicating that these countries have made full use of national resources to achieve the minimum ASMR level (Supplementary Table 9).

(A) LC, (B) LCB, (C) LCC. The black line represents the frontier line (optimal ASMR corresponding to each sociodemographic index), green dots represent countries and regions with the lowest ASMR, light blue dots represent the predicted ASMR for each country in 2050, red dots represent the top 10 countries with the greatest effective differences, and orange dots represent the top five countries by population: China, India, the United States, Indonesia, and Brazil. ASMR: Age-standardized mortality rate; LC: Liver cancer; LCB: Liver cancer due to hepatitis B; LCC: Liver cancer due to hepatitis C.

Global ASMR for LC will show little change between 1990 and 2050, but some countries will experience significant changes. About 72 % of countries will see a decrease in ASMR for LC from 2022 to 2050 (Fig 4). The top 10 countries with an increase in ASMR will all be developing nations, with Mongolia, Gambia, and Mali showing ASMR changes of >30 % (Supplementary Table 10). For LCB, 30 % of countries globally will see reduced ASMR from 2022 to 2050 (Supplementary Table 11, Supplementary Fig 3), while for LCC, 44 % of countries will show an increase in ASMR (Supplementary Table 12, Supplementary Fig 4). The global ASMR for LC will decrease at a rate of 0.02 per year from 1990 to 2050 (Fig 5a). The ASMR for LCB will decrease at a rate of 0.01 per year (Fig 5c), while the ASMR for LCC showed a sharp decline during 2001–2021 (Fig 5e). After 2022, the ASMR of LCC in the United States, China, and India is expected to continue to rise, with slower increases in Indonesia and Brazil (Fig 5f).

(A) Common time trends of LC, (B) Time effects of LC deviating from the common trend in China, the United States, Brazil, India, and Indonesia, (C) Common time trends of LCB, (D) Time effects of LCB deviating from the common trend in China, the United States, Brazil, India, and Indonesia, (E) Common time trends of LCC, (F) Time effects of LCC deviating from the common trend in China, the United States, Brazil, India, and Indonesia. LC: Liver cancer; LCB: Liver cancer due to hepatitis B; LCC: Liver cancer due to hepatitis C.

Decomposition analysis shows that population growth and age structure were the main contributors to the increase in LC deaths globally and in Southeast Asia during 1990–2021 (Supplementary Fig 5). From 2022–2050, age structure will be the primary driver for increased LC deaths globally, except in Africa. In the WPR, age structure will be the main factor for changes in LC death rates between 1990 and 2050. Epidemiological changes positively contributed to the reduction in global LC deaths from 1990 to 2021, with the reduction in LCB deaths primarily driven by epidemiology and age structure (Supplementary Fig 6). Population growth will continue to affect LC, LCB, and LCC deaths in Africa (Supplementary Fig 7, Supplementary Table 13).

4DiscussionIn this study, we evaluated the disease burden of LC deaths globally, across six WHO regions, and in 204 countries or territories from 1990–2021, with projections to 2050. Viral hepatitis remains the leading cause of LC-related deaths, accounting for 70 % of total LC deaths in the past 30 years. From 1990 to 2021, the global ASMR of LC remained stable, the ASMR of LCB showed a downward trend, and the ASMR of LCC remained stable. This trend aligns with recent studies suggesting a continued decline in both incidence and mortality of LCB and LCC through 2050 [19]. This decline likely reflects decreasing seropositivity for HBV/HCV and the effect of antiviral treatment on preventing the progression of the liver disease, as well as reduced exposure to factors such as aflatoxin [20]. If a patient is chronically infected with HBV, exposure to aflatoxin B1 will increase the risk of LC [21]. When the ratio of exposure to aflatoxin alone is 6.37, and the ratio of chronic HBV infection is 11.3, the combined impact ratio of chronic HBV infection and aflatoxin exposure rises to 73.0 [22]. These estimates indicate that the effects of aflatoxin exposure and chronic HBV infection on the risk of HCC are multiplicative [23]. A Chinese study estimated that by changing the staple food from corn to rice, the mortality rate of primary liver cancer could be reduced by 65 %; 83 % of the benefits were seen in the population infected with HBV [24]. In addition, studies have shown that HCV plays a significant role in causing chronic liver diseases and leading to LC [25]. We also found differences in LC mortality by sex, age, and region. LC mortality ranks second among men, with male predominance in HBV-related LC. The proportion of HCV-related LC deaths is higher in women than men, whereas HBV-related deaths are twice as high in men. Sex differences in ASMR of LC are evident, particularly for LCB, where males bear a significantly higher burden than female. Studies have shown that males are more likely to be exposed to HBV transmission routes due to occupational factors, unsafe injections, and blood exposure [26]. Moreover, biological mechanisms may contribute: androgens have been shown to enhance HBV replication and suppress immune responses, thereby increasing liver cancer risk, whereas estrogens may reduce risk by inhibiting inflammatory pathways and oxidative stress [27,28]. These factors contribute to the higher incidence of LCB in males than that in females. However, the sex difference in LCC is smaller, and in some regions, such as Africa and Southeast Asia, ASMR in females slightly exceeds that of males. One possible explanation is that in certain regions, historical HCV transmission has been linked to medical procedures, including childbirth and transfusions, leading to greater exposure among females. Additionally, female’s longer life expectancy may contribute to higher cumulative LCC mortality [26].

Although non-viral factors increasingly contribute to the LC burden, viral hepatitis elimination remains a critical strategy for primary prevention [29,30]. The global burden of hepatitis virus-related LC will remain high, with significant regional and gender differences. Targeted public health policies should focus on high-burden regions to reduce this global burden. Since the launch of the global hepatitis elimination targets in 2016 [31,32], many countries have made progress in eliminating HBV and HCV. The WHO target aims to reduce the incidence of HBV and HCV infection by 90 % and their associated mortality by 65 % by 2030 [33]. However, the global goal of HBV and HCV elimination by 2030 is unlikely to be met, and hepatitis virus-related LC will continue to be a major issue. Currently, only 43 % of the global population receives the hepatitis B vaccine at birth, with Africa’s coverage at just 6 % [34]. Preventing infection, controlling hepatitis viruses, and improving LC diagnosis and treatment are crucial to reduce LC deaths. At the same time, not only it is necessary to improve the access to vaccines and antiviral drugs, but liver cancer screening programs also need to be adjusted according to the specific circumstances of each country [23]. Raising the third dose of HBV vaccine coverage, providing hepatitis B immunoglobulin to newborns, offering perinatal antiviral prophylaxis to HBeAg-positive pregnant women, and providing antiviral treatment to adult patients with chronic hepatitis B who meet the treatment criteria will help achieve the WHO's goal of eliminating hepatitis B by 2030. By improving access to HCC screening, the goal of eliminating viral hepatitis by 2030 can be accelerated [23]. Notably, we observed significant SDI-related inequalities, with lower SDI countries bearing a disproportionately high burden of LC deaths. The national inequalities related to LC, LCB, and LCC burden in different SDI regions have decreased over time. The high ASMRs of LC and LCB were all in the middle SDI region. Among women, the ASMRs of LCB and LCC were highest in low-income countries and low SDI regions, which shows a lack of viral hepatitis prevention and control and chronic disease management among women in regions with low economic development. Among the regions with different income levels, efforts need to be made to improve the high ASMR of LC in low-income areas and high LC deaths in upper-middle income areas. A high ASMR of LCC was observed in high-income countries and high SDI areas. In high-income countries, those most at risk are often vulnerable populations including illegal immigrants, drug users, incarcerated people, and the homeless and poor, all of whom have low access to health care resources. The burden of viral testing and treatment is currently a major barrier [35]; therefore, local governments and public health organizations need to expand screening and treatment interventions for viral hepatitis [36,37]. The transmission routes vary in epidemic areas and non-epidemic areas. In epidemic areas, vertical transmission from mother to child and horizontal transmission among children are the most common routes of HBV infection. In non-epidemic areas, intravenous drug use and sexual transmission between adults are the main infection causes. And intravenous drug users are the patient group least likely to seek regular medical care and adhere to the antiviral treatment course. Special treatment plans for hepatitis virus must be improved for specific groups to reduce the treatment burden and improve the accessibility of medical services [38].

In regions like Asia, where LC-related deaths are highest, the highest ASMRs of LC and LCB persist. Africa has the highest ASMRs for LCC. Between 1990–2021, the highest ASMR for LCC shifted from the WPR to the EMR, which was associated with a historically higher HCV-related disease burden. In the EMR, especially in Egypt, the prevalence of HCV is high due to iatrogenic transmission (cross infection during injection therapy) during the schistosomiasis treatment campaigns of the 1960s and 1970s [39,40]. Despite increased blood-product monitoring since then, the cumulative long-term consequences of historical infections, particularly in patients with advanced cirrhosis, continue to contribute to the burden of LCC mortality in this region. From 2021 to 2050, high ASMRs of LCB are expected in East Asia, Southeast Asia, West Africa, and Central Africa. It is reported that over the past 40 years, the proportion of HBV in China has generally been on the rise, while the proportions of HCV and co-infection have been on the decline [26]. However, all the ASMR of LC, LCB, and LCC decreased in China during 1990–2021. Hepatitis B mortality is projected to decrease in North and South America [2,19]. In the Americas, LCC mortality is rising fastest, while the WPR shows the greatest decline. Despite declining HBV and HCV-related LC rates globally, regions like Mongolia, with the highest incidence and mortality of HBV/HCV-related LC, still face challenges [41]. The burden of HBV and HCV related LC in Mongolia is extremely heavy [42]. Moreover, the population in Mongolia that receives intravenous injections is >10 times the world average. Therefore, the control and health management of intravenous injections in Mongolia should be strengthened. In East Asia, Southeast Asia, West Africa, and Central Africa, efforts should continue to vaccinate newborns and adults. Measures should be taken to block transmission through blood, mother-to-child [43], and sexual routes. In March 2024, the WHO released revised guidelines on the prevention and management of chronic hepatitis B. Simplifying the care process and expanding the treatment standards were the core contents of this revision [44]. To cure HCV, and particular attention should be paid to Africa, the Americas, and the EMR. Most HCV infections occur through unsafe injection behaviors, unsafe medical care, unscreened blood transfusions, injection drug use (IDU), and sexual behaviors that lead to blood exposure. Study from Vietnam has shown that community-based organizations and strategies ranging from large-scale HCV screening to prevention of reinfection provides highly promising solutions for eliminating HCV among IDU in low-income and middle-income countries [45]. In addition, our previous study has shown that implementing five universal screening strategies for people aged 18 to 70 within the next 10 years is the most optimal HBV screening strategy applicable to China [37].

The deaths of patients with LC vary by geographic region and race, in large part due to differences in viral infections. Hepatitis C is a major risk factor for LC in the United States, Europe, and Japan [46]. HBV vaccination has been a major public health success and has significantly reduced HBV infection rates and LC incidence in high-risk East Asian countries since it was first introduced in the early 1980s [47]. Occult HBV infection is also associated with increased risk because of DNA damage induced by viral integration. Most HCV infections occur through unsafe injection practices, unsafe health care, unscreened blood transfusions, injection drug use, and sexual practices that lead to blood exposure [48,49]. Thus, enhanced blood transfusion screening, prevention of mother-to-child transmission, and provision of clean needles are key to HCV control [35]. Despite no vaccine, DAAs can cure HCV infection in most cases [50]. And antiviral therapy reduces HCC risk and improves survival among patients with HBV/HCV-related liver diseases [51,52]. However, patients with cirrhosis remain at high risk of developing LC even achieved SVR after DAA treatment [53]. Therefore, it is important to increase screening for HBV and HCV, initiate antiviral therapy for all patients who meet the recommended treatment criteria [36,37], and offer antiviral therapy to patients with HCV- or HBV-related HCC, even for advanced HCC patients with a limited life expectancy [54–56]. The CDC of the United States has released recommendations for the identification and public health management of chronic HBV infection, which could provide experience for other regions with poor control [57].

The treatment outlook for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma has improved. Surgical therapy still offers the best long-term survival outcome for early-stage LC patients. Systemic therapy has greatly changed the treatment landscape for advanced unresectable LC. Patients with advanced unresectable tumors mainly rely on transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), TARE, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), etc. The WHO has set a global health goal of eliminating the viral hepatitis threat by 2030 through vaccination, screening and treatment programs [58]. However, the elimination plan for viral hepatitis has been hindered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on the published studies, all stages of the viral hepatitis treatment process in different centers have been affected by the pandemic [59]. The number of patients receiving HBV or HCV treatment in 2020 decreased by 20 % and 52 % respectively compared to 2019. The results of a survey by the Global Hepatitis Elimination Alliance show that 39 % and 21 % of the respondents reported that the treatment volume for hepatitis C and hepatitis B has decreased by >50 % [60]. Despite the telemedicine improved the compliance of patients with DAA treatment [61], our previous study showed the COVID-19 pandemic have an obvious impact on the mortality rate of chronic liver diseases, patients with liver cirrhosis experienced an astonishing increase, both directly and indirectly mortality [62–65].

Unlike previous studies focusing on historical data, we used the latest GBD 2021 dataset and advanced quantitative methods to examine LC mortality trends. The Bayesian spatiotemporal model provided a comprehensive analysis of global LC mortality patterns, and the frontier analysis identified the optimal ASMR for each country by 2050. This study contributes novel insights for public health planning and policy development, offering predictive data for future mortality trends. Our research reveals the trends of disease evolution and the gaps in prevention and control, supporting policy formulation and health economics assessment, dynamically adjusting national screening strategies, and promoting the implementation of tiered medical care. Our study had several limitations. Firstly, GBD 2021 does not include data from all regions, particularly in areas with poor sanitation and limited epidemiological data. Secondly, there were biases in the mortality burden and prediction models, although we minimized these through advanced modeling techniques. Thirdly, the impact of COVID-19 on LC mortality was not included in this analysis, as GBD 2021 assessed additional health issues due to COVID-19. The COVID-19 pandemic is a potential interfering factor for the estimated number of liver cancer deaths in 2050. In the predictive analysis, we did not take into account the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on liver cancer deaths. Fourthly, the latent hepatitis virus infection might have been underestimated, and this could indeed have an impact on the estimation of LCC/LCB mortality in our study. Fifthly, the resolution of obstacles related to vaccination coverage and access to treatment drugs is the biggest source of uncertainty in the prediction. In countries with low SDI, due to limitations in medical conditions, there is inevitably a lack of diagnosis for hepatitis virus infections and hepatitis virus-related liver cancers. Therefore, LCB/LCC mortality may be underestimated. The BAPC model does not account for future external shocks such as expanded healthcare access, changes in vaccination coverage, or medical breakthroughs. As such, the projections should be interpreted as baseline trend estimates under current trajectories. Finally, while we focused on viral hepatitis-related LC, GBD 2021 also accounts for other LC causes such as alcohol use and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

5ConclusionsOur study showed Asia bears the highest global burden of LC deaths The WPR had the highest ASMR for LC and LCB. ASMR for LC showed the fastest decrease in WPR. The Americas had the lowest ASMR but the highest increase in ASMR for LC. For women, Africa had the highest ASMR for LC and LCB. For LCC, the largest increase of ASMR occurred in the Americas, and the fastest decline was seen in the WPR. The highest ASMR for LCC shifted from the WPR in 1990 to the EMR in 2021. High ASMRs are prevalent in middle SDI areas for LC and LCB, while high-income countries face the highest ASMRs for LCC. Aging and population growth are the main factors driving LC mortality increases. This study provides valuable data for understanding the temporal, spatial, and future trends of LC mortality, which may guide more effective health policies and reduce global health inequities.

Author contributionsYuan Wang, Yujiao Deng, Yang and Fanpu Ji had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Yujiao Deng and Jingyue Tan contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Study concept and design: Yujiao Deng, Jian Zu, Yuan Wang, Fanpu Ji. Acquisition of data: Yujiao Deng, Jingyue Tan, Zixuan Xing, Enrui Xie. Analysis and interpretation of data: Yujiao Deng, Jingyue Tan, Zixuan Xing, Enrui Xie. Drafting of the manuscript: Yujiao Deng, Jingyue Tan, Zixuan Xing, Zhanpeng Yang. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Yujiao Deng, Yajing Bo, Xu Gao, Meijuan Han, Fanpu Ji. Statistical analysis: Yujiao Deng, Jingyue Tan, Zixuan Xing, Yue Zhang, Zhanpeng Yang. Design and production of figures and tables: Yujiao Deng, Jingyue Tan, Zhanpeng Yang. Obtained funding: Yujiao Deng, Fanpu Ji. Administrative, technical, or material support: Yujiao Deng, Jian Zu. Supervision: Yujiao Deng, Fanpu Ji.

FundingThis study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82,170,626, No. 82,473,291, No. 82,403,188) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. xtr062023003), Health and Wellness Scientific Research and Innovation Project of Shaanxi Province (No. 2025TD-09). The funding body did not play role in the design, conduct, or reporting of the study.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank all members of our study team for their cooperation and the Global Burden of Disease Study collaborators for their work.

None.

![(A) 1990–2021, (B) 1990–2050, (C) 2022–2050. S[i] represents the disparity in ASMR of the i th country or territory compared to the global average level α throughout the entire study period. ASMR: Age-standardized mortality rate; LC: Liver cancer. (A) 1990–2021, (B) 1990–2050, (C) 2022–2050. S[i] represents the disparity in ASMR of the i th country or territory compared to the global average level α throughout the entire study period. ASMR: Age-standardized mortality rate; LC: Liver cancer.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/16652681/0000003100000001/v17_202512250514/S1665268125003692/v17_202512250514/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr4.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)