The global increase in obesity and aging populations has led to a higher prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) among patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB), particularly in Asia (with prevalence increasing from 3.93% in 1990 to 10.26% in 2019, according to a study on the global burden of the CHB population in the Western Pacific Region) [1,2]. In addition to the hepatitis B virus (HBV), T2DM is also recognized as a significant risk factor for liver-related events (LREs) in patients with CHB [3–6]. A recent study found that a high glycemic burden was also linked to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) independently of antiviral therapy (AVT) use and serum HBV-DNA levels [7–11]. This finding underscores the importance of maintaining good glycemic control to reduce the risk of LREs.

Within the category of oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs), sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) have been shown to mitigate the risk of various comorbidities linked to T2DM, such as cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney diseases, according to evidence derived from recent randomized clinical trials [12,13]. Moreover, several studies have also highlighted the hepatic benefits of SGLT2i on LREs including steatotic liver disease, liver fibrosis, and HCC in patients with T2DM [14–18]. Lee et al. [19] recently observed that SGLT2i use was associated with a lower incidence of HCC than non-use was in CHB patients with T2DM. More recently, Chou et al. [20] reported the advantageous effect of SGLT2i compared with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP4i) on HCC risk among patients with CHB and T2DM. However, the limited follow-up period and potential confounding factors inherent to observational studies necessitate a more comprehensive design to enhance the robustness and reliability of the results.

Therefore, we aimed to investigate whether SGLT2i significantly reduced the risk of LREs compared with DPP4i, one of the most widely used secondary OADs, among the “at-risk population”, i.e. CHB patients with T2DM, using a nationwide cohort and a target trial emulation design. This novel method is designed to avoid fundamental errors that can lead to misleading causal conclusions.

2Materials and Methods2.1Target trial emulationThis cohort study employed a target trial emulation design to improve the accuracy of causal effect estimates by replicating the fundamental characteristics of a Randomized Clinical Trial using observational data (Table S1)., [21] Target trial emulation refers to the process of designing observational studies to mimic the structure of a randomized trial, enabling more robust causal inference by reducing biases such as immortal time bias, and improving the validity of comparisons between treatment strategies. This study adhered to the ethical principles of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Yonsei University Hospital (IRB number: 4-2022-0664). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study.

2.2Data source and study populationsThis cohort study utilized the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database, covering 97.2% of the population in the Republic of Korea [22]. The database offers demographic and socioeconomic information, details on outpatient visits or hospital admissions with diagnostic codes, medication prescriptions, and biannual comprehensive health check-up data for eligible adults [23]. These check-ups include lifestyle information and various clinical and biochemical assessments.

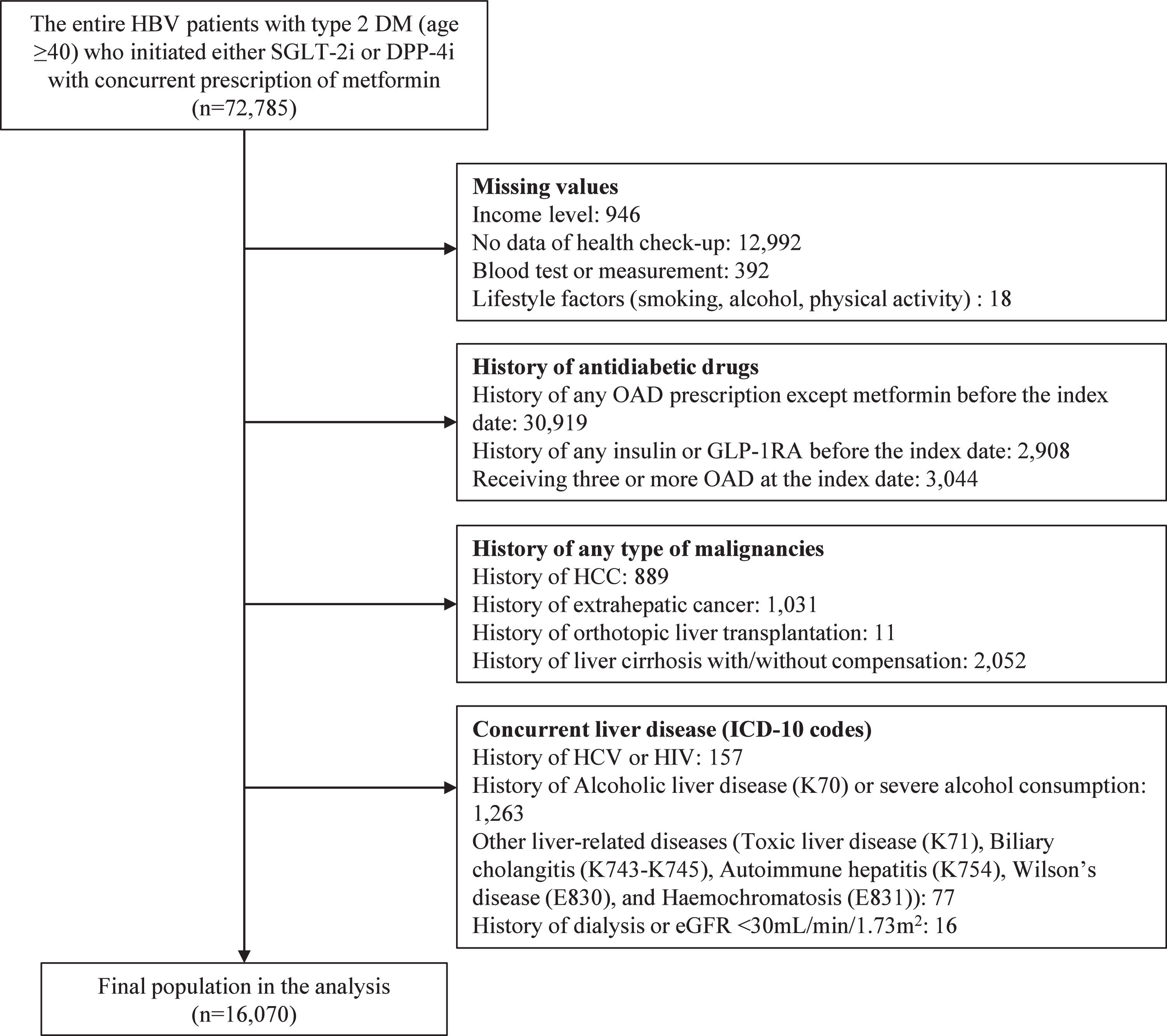

Patients for this study were identified based on the following criteria: (1) age ≥40 years; (2) diagnosis of T2DM (ICD-10: E11–E14); and (3) initiation of DPP4i or SGLT2i alongside metformin between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2020. The index date was defined as the initiation date of either DPP4i or SGLT2i. Patients were excluded if they had: (1) missing household income data; (2) no health check-up results; (3) missing data within the check-up data; (4) prior use of any OADs except metformin; (5) prior use of any injectable antidiabetic drugs, such as insulin or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; (6) three or more OADs prescribed at the index date; (7) history of LRE, including HCC, liver cirrhosis (LC) with or without decompensation, and orthotopic transplantation; (8) history of extrahepatic malignancies; (9) history of hepatitis C virus (HCV) or human immunodeficiency virus infection; (10) history of concurrent liver diseases, such as alcoholic liver disease (K70), severe alcohol consumption (weekly intake ≥420 g for men or ≥350 g for women), toxic liver disease (K71), biliary cholangitis (K74.3–K74.5), autoimmune hepatitis (K75.4), Wilson’s disease (E83.0), and hemochromatosis (E83.1); and (11) estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a history of dialysis. The inclusion and exclusion processes are summarized in Figure 1.

2.3Study outcomesThe primary endpoint of this study was LRE, encompassing HCC, LC with or without decompensation, orthotopic liver transplantation, and liver-related mortality. The primary outcome was the earliest occurrence of any LRE. The diagnosis date of HCC was identified based on the earliest hospital record with the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code C22.0, along with the V193 code. The V193 code pertains to a registration program initiated by the Republic of Korea in 2006 to reduce copayments for rare and intractable diseases., [24] LC, with or without decompensation, was defined based on hospital visits or procedural records of LC complications. Participants were monitored until the onset of any LRE, death, or December 31, 2022, whichever occurred first.

Secondary outcomes included HCC, LC with or without decompensation, and all-cause mortality. The precise definitions of these diseases are presented in Table S2. For the analysis of secondary outcomes, participants were followed up until the occurrence of each specific event, death, or December 2022, whichever came first.

2.4ExposureWe employed an as-treated (per-protocol) approach to define the exposure. Patients were monitored from the day following the initiation of their index medications (SGLT2i or DPP4i) until a study outcome occurred. We censored participants upon discontinuation (or switching) of the index drug, death, or the end of the study period (December 31, 2022), whichever came first. Treatment discontinuation was defined as a gap exceeding 60 days between consecutive prescriptions [25].

DPP4i was chosen as the comparator drug due to its similarity to SGLT2i in being a second- or third-line OAD for managing T2DM. Selecting DPP4i as the comparator aimed to minimize potential biases arising from confounding factors, such as indication bias or variations in disease severity among patients with T2DM.

2.5CovariatesAge, sex, household income quartile, Body Mass Index (BMI), hypertension, diabetic complications, uncontrolled fasting blood sugar ([FBS], ≥126 mg/dL), duration of diabetes, AVT, abnormal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level, smoking history, alcohol consumption, and physical activity were used as covariates. We utilized a 2-year retrospective review of hospital utilization records prior to the index date, including disease diagnoses and drug prescriptions. Additionally, the most recent health check-up data (BMI, blood pressure (BP), FBS, ALT level, and lifestyle factors) from the past 4 years prior to the index date were incorporated.

Household income levels were categorized into four groups (high, high-middle, low-middle, and low) based on the premium insurance paid. BMI was classified in accordance with the 2022 Update of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity as follows: normal or underweight (<23 kg/m²), overweight (23–24.9 kg/m²), class I obesity (25–29.9 kg/m²), and class II obesity or higher (≥30 kg/m²)., [26]

The presence of hypertension was defined as having a history of antihypertensive drug prescription with a related ICD-10 code (I10–13, I15), systolic BP ≥140 mmHg, or diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg. An abnormal ALT level was defined as ALT ≥34 U/L for men and ≥25 U/L for women, respectively, based on health check-up results [27]. Diabetic patients with complications were identified as those having a diagnosis of diabetes accompanied by conditions such as coma, acidosis, renal, ophthalmic, neurological, cardiovascular complications, or other multiple comorbidities. The duration of diabetes was treated as a binary variable, categorized as either 1 year or more, or less than 1 year.

Individuals were classified as nonsmokers, ex-smokers, or current smokers based on the responses to lifestyle questionnaires. Alcohol consumption was categorized into two groups and used as a covariate: <210 g/week and 210–419 g/week for men and <140 g/week and 140–349 g/week for women, respectively [28]. For physical activity, the weekly minutes of vigorous physical activity were doubled and then combined with the weekly minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity before classification into inactive group (<150 min/week) or active group (≥150 min/week) [29].

2.6Statistical analysisThe baseline characteristics of the individuals are reported as median (interquartile range) or count (%), as appropriate. The cumulative incidence of LRE between the SGLT2i and DPP4i groups was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for primary and secondary outcomes were estimated using multivariable Cox proportional hazards models.

To minimize confounding bias, propensity score (PS) matching was performed using all baseline covariates (age, sex, household income quartile, BMI, hypertension, diabetes complication, uncontrolled FBS, duration of diabetes, AVT, abnormal ALT level, smoking history, alcohol consumption, and physical activity). The nearest neighbor method with a 1:2 ratio and a greedy caliper width of 0.05 was applied. The balance between the two groups (SGLT2i vs. DPP4i) was evaluated using the standardized mean difference (SMD) to ensure appropriate matching. The risk of LRE was assessed in the matched cohort using the same method as in the main analysis.

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted to ensure the robustness of the results. First, Cox analysis with inverse probability treatment weighting (IPTW) was performed. Second, a competing risk analysis was performed using Fine and Gray regression, considering all-cause mortality, except liver-related mortality, as a competing risk. Third, the grace period for defining treatment discontinuation varied between 45 and 90 days to prevent the potential misclassification of exposure. Fourth, a stratified analysis was performed to evaluate the difference in the risk of LRE between the two groups.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R 4.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All results were considered significant at a two-sided p-value <0.05.

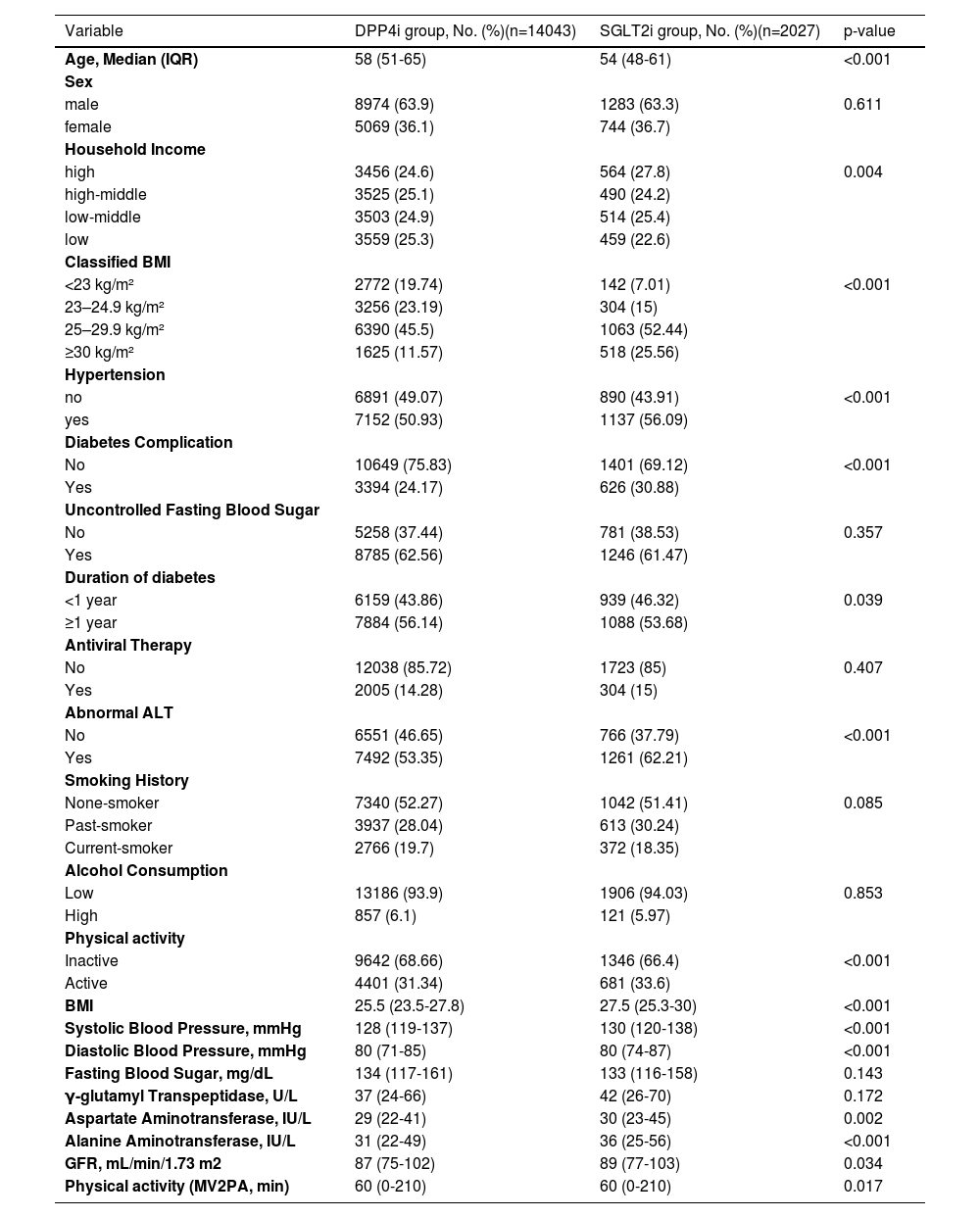

3Results3.1Baseline characteristicsAmong 72,785 patients with CHB and T2DM who initiated SGLT2i or DPP4i alongside metformin, 16,070 met the inclusion criteria for the final analysis cohort (Figure 1). The cohort had a median age of 57 years (interquartile range: 50–64 years), with 66.9% being male. Compared with the DPP4i group, patients in the SGLT2i group (12.6%, n=2,027) were younger and exhibited a higher prevalence of high-income status, hypertension, diabetes complications, longer diabetes duration, abnormal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, higher body mass index (BMI), greater physical activity, elevated liver enzyme levels, and higher estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). All differences between the groups were statistically significant (p < 0.05, Table 1).

Baseline Characteristics of DPP4i and SGLT2i users in the entire cohort (n=16,070).

Values are expressed as N (%) or median (interquartile range), as appropriate.

Abbreviation: DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; SGLT-2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; BMI, body mass index; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GFR, glomerular filtration rate

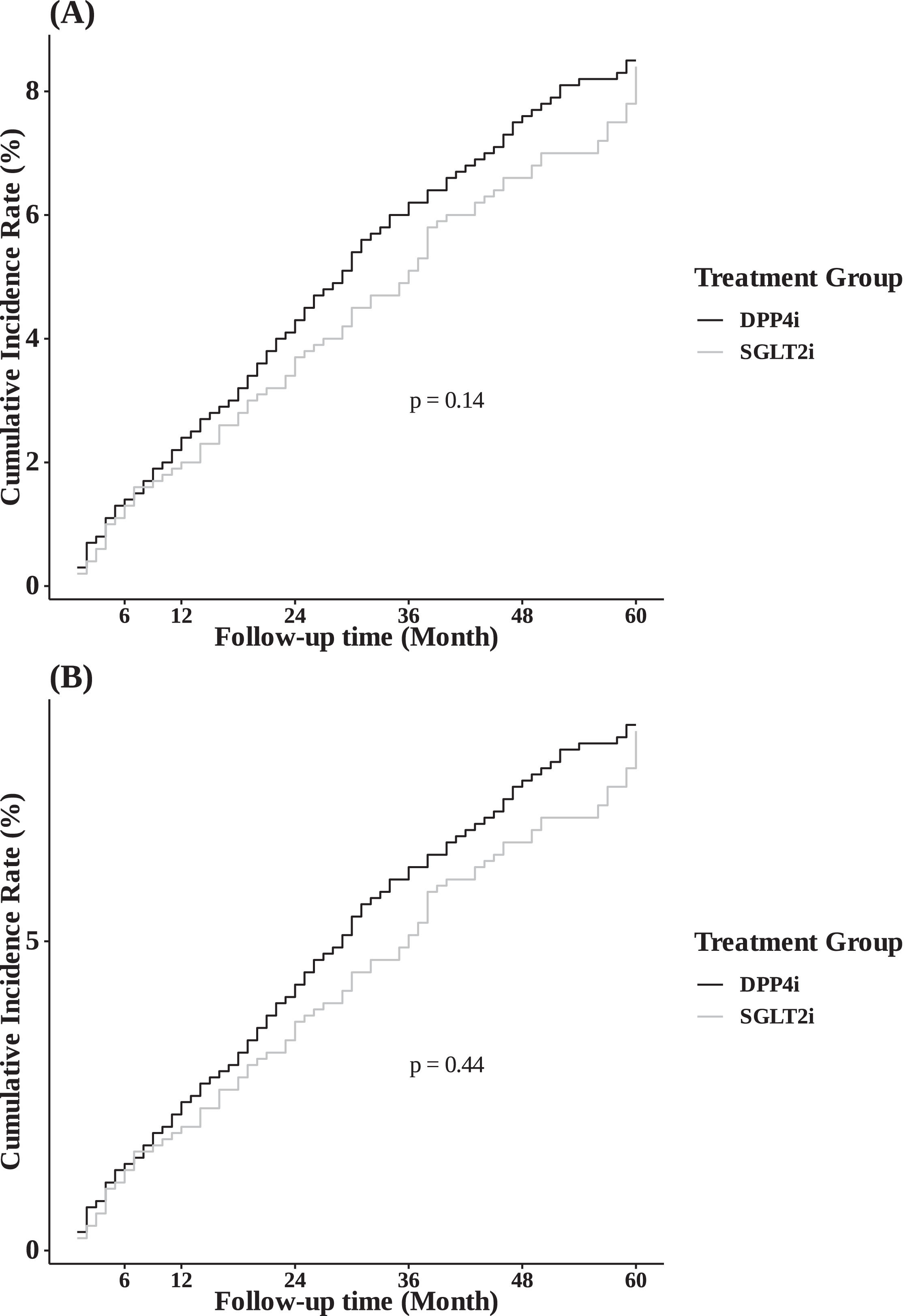

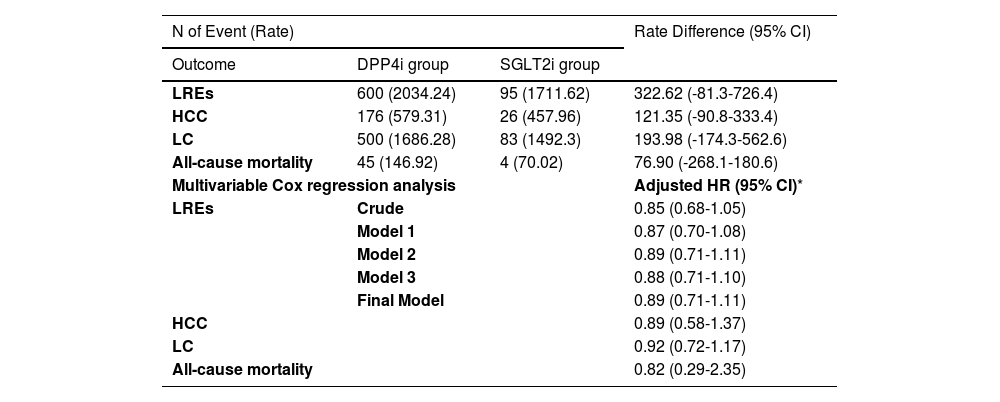

During a median follow-up period of 2.1 years, 695 participants (4.3%) developed LRE. The 5-year cumulative incidence of LRE showed no significant difference between the SGLT2i and DPP4i groups in the entire cohort (8.4% vs. 8.5%, respectively; Figure 2A; p = 0.14). Multivariate Cox regression analysis, adjusted for factors such as age, sex, income, and health conditions (BMI, hypertension, diabetes complications, uncontrolled FBS, AVT, abnormal ALT, smoking history, alcohol consumption, and physical activity), revealed a comparable risk of LRE between the SGLT2i and DPP4i groups (aHR 0.89, 95% CI 0.71–1.11) (Table 2).

The Risk of LREs and secondary outcomes between the SGLT2i vs. DPP4i groups based on target trial emulation in the entire cohort.

| N of Event (Rate) | Rate Difference (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | DPP4i group | SGLT2i group | |

| LREs | 600 (2034.24) | 95 (1711.62) | 322.62 (-81.3-726.4) |

| HCC | 176 (579.31) | 26 (457.96) | 121.35 (-90.8-333.4) |

| LC | 500 (1686.28) | 83 (1492.3) | 193.98 (-174.3-562.6) |

| All-cause mortality | 45 (146.92) | 4 (70.02) | 76.90 (-268.1-180.6) |

| Multivariable Cox regression analysis | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | ||

| LREs | Crude | 0.85 (0.68-1.05) | |

| Model 1 | 0.87 (0.70-1.08) | ||

| Model 2 | 0.89 (0.71-1.11) | ||

| Model 3 | 0.88 (0.71-1.10) | ||

| Final Model | 0.89 (0.71-1.11) | ||

| HCC | 0.89 (0.58-1.37) | ||

| LC | 0.92 (0.72-1.17) | ||

| All-cause mortality | 0.82 (0.29-2.35) | ||

Rate are expressed as per 100,000 person years

Reference: DDP4i group

Model 1: adjusted by age, sex, and household income

Model 2: adjusted by age, sex, household income, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes complication, duration of diabetes, and uncontrolled fasting blood sugar

Model 3: adjusted by age, sex, household income, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes complication, duration of diabetes, uncontrolled fasting blood sugar, antiviral therapy, and abnormal alanine aminotransferase

Final Model: adjusted by age, sex, household income, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes complication, duration of diabetes, uncontrolled fasting blood sugar, antiviral therapy, abnormal ALT, smoking history, alcohol intake, and physical activity

Abbreviation: LRE, liver-related event; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase4 inhibitors; TTE, target trial emulation; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

The risk of secondary outcomes was estimated using the adjusted variables of the final model.

The incidences of secondary outcomes were as follows: HCC, 202 cases (1.3%); LC with or without decompensation, 583 cases (3.6%); and all-cause mortality, 49 cases (0.3%). Similar to the findings for LRE, the risks of these secondary outcomes in the SGLT2i group were comparable to those in the DPP4i group, as indicated by the aHRs (Table 2): HCC, aHR 0.89 (95% CI 0.58–1.37); LC with or without decompensation, aHR 0.92 (95% CI 0.72–1.17); and all-cause mortality, aHR 0.82 (95% CI 0.29–2.35).

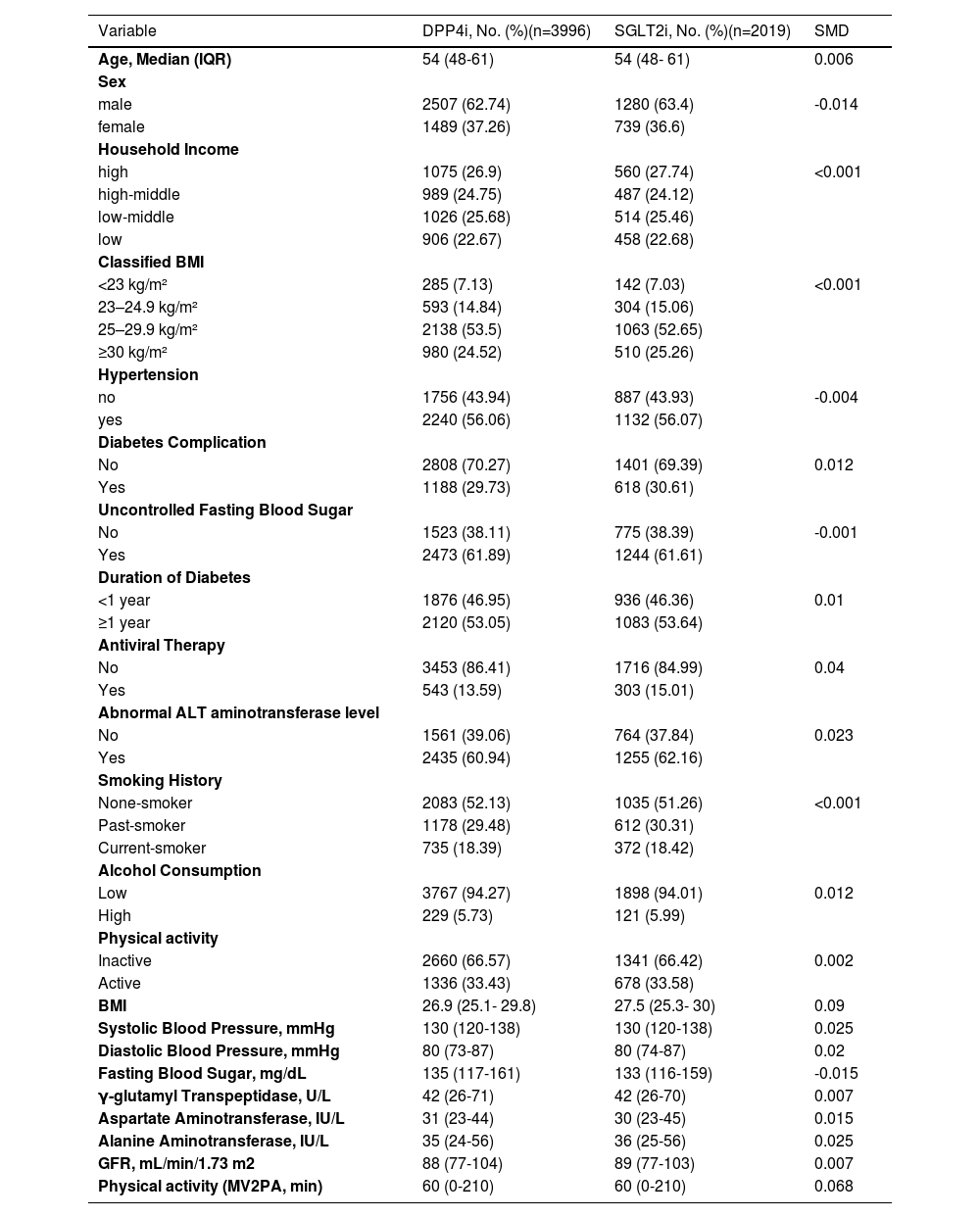

3.3Outcomes in the PS-matched cohortPropensity score (PS) matching was performed using a 1:2 ratio and a greedy caliper width. This process yielded approximately 2,000 matched pairs (2,019 for the SGLT2i group and 3,996 for the DPP4i group). As shown in Table 3, matching achieved a good balance between the two groups across all baseline covariates (SMD < 0.1).

Baseline Characteristics of DPP4i and SGLT2i users in the PS-matched cohort (n=6,007).

Values are expressed as N (%) or median (interquartile range), as appropriate.

Abbreviation: DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; SGLT-2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; SMD, standardized mean difference; BMI, body mass index; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GFR, glomerular filtration rate

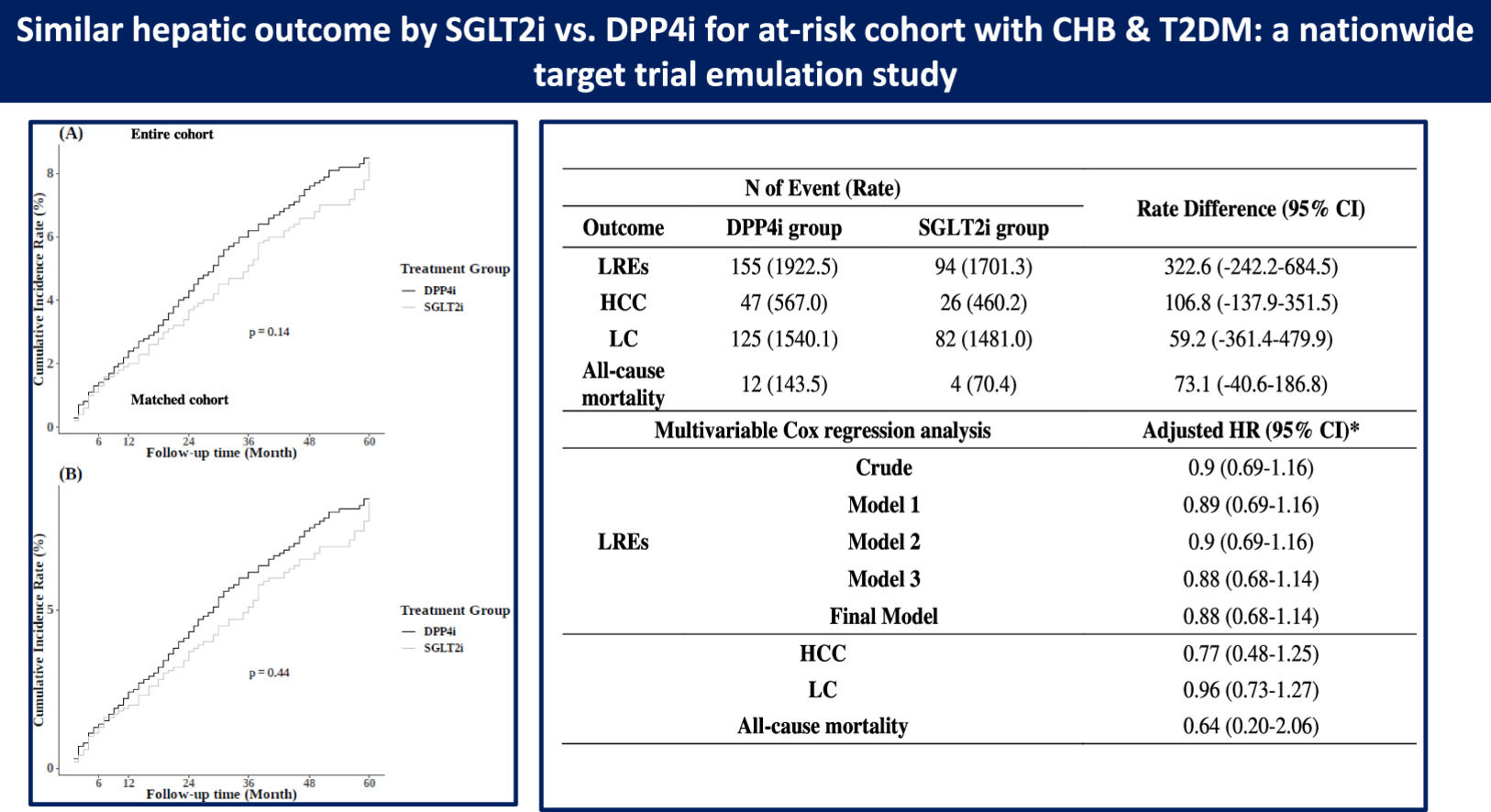

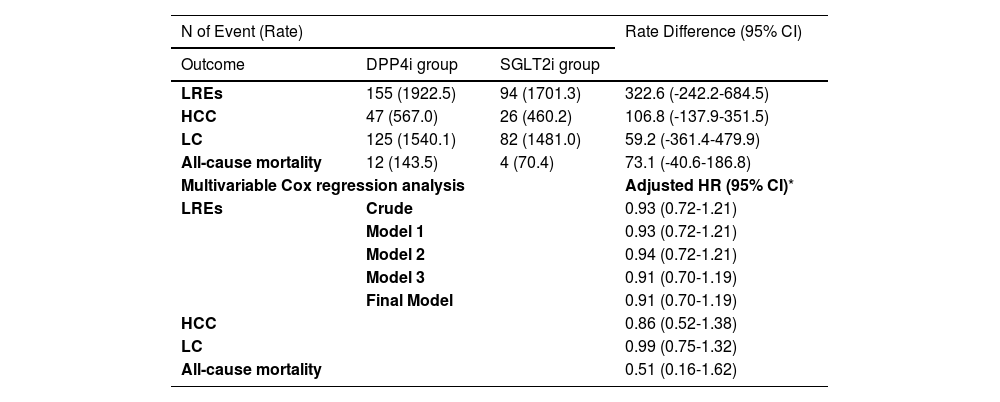

Participants in the PS-matched cohort were followed for a median of 2.3 years. During this period, 243 participants (4.0%) developed LRE. The 5-year cumulative incidence of LRE remained similar between the SGLT2i and DPP4i groups (8.3% vs. 8.0%, respectively; Figure 2B), with no significant difference (p = 0.44). Consistent with the main analysis, multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed a comparable risk of LRE in the PS-matched cohort (aHR 0.91, 95% CI 0.70–1.19) (Table 4).

The Risk of LREs and secondary outcomes between the SGLT2i vs. DPP4i groups based on target trial emulation in the PS-matched cohort.

| N of Event (Rate) | Rate Difference (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | DPP4i group | SGLT2i group | |

| LREs | 155 (1922.5) | 94 (1701.3) | 322.6 (-242.2-684.5) |

| HCC | 47 (567.0) | 26 (460.2) | 106.8 (-137.9-351.5) |

| LC | 125 (1540.1) | 82 (1481.0) | 59.2 (-361.4-479.9) |

| All-cause mortality | 12 (143.5) | 4 (70.4) | 73.1 (-40.6-186.8) |

| Multivariable Cox regression analysis | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | ||

| LREs | Crude | 0.93 (0.72-1.21) | |

| Model 1 | 0.93 (0.72-1.21) | ||

| Model 2 | 0.94 (0.72-1.21) | ||

| Model 3 | 0.91 (0.70-1.19) | ||

| Final Model | 0.91 (0.70-1.19) | ||

| HCC | 0.86 (0.52-1.38) | ||

| LC | 0.99 (0.75-1.32) | ||

| All-cause mortality | 0.51 (0.16-1.62) | ||

Rate are expressed as per 100,000 person years

Reference: DDP4i group

Model 1: adjusted by age, sex, and household income

Model 2: adjusted by age, sex, household income, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes complication, duration of diabetes, and uncontrolled fasting blood sugar

Model 3: adjusted by age, sex, household income, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes complication, duration of diabetes, uncontrolled fasting blood sugar, antiviral therapy, and abnormal alanine aminotransferase

Final Model: adjusted by age, sex, household income, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes complication, duration of diabetes, uncontrolled fasting blood sugar, antiviral therapy, abnormal ALT, smoking history, alcohol intake, and physical activity

Abbreviation: LRE, liver-related event; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase4 inhibitors; TTE, target trial emulation; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; PS, propensity score

The risk of secondary outcomes was estimated using the adjusted variables of the final model.

Similar trends were observed for the secondary outcomes, with incidences as follows: 73 cases (1.2%) for HCC, 16 (0.3%) for all-cause mortality, and 207 (3.4%) for LC with or without decompensation.The risks of HCC (aHR 0.86, 95% CI 0.52–1.38), LC with or without decompensation (aHR 0.99, 95% CI 0.75–1.32), and all-cause mortality (aHR 0.51, 95% CI 0.16–1.62) were comparable between the SGLT2i and DPP4i groups in the PS-matched cohort, as shown in Table 4.

3.4Sensitivity analysisAll sensitivity analyses yielded consistent results (Table S3). The risk of LRE among participants in the SGLT2i group was comparable to that in the DPP4i group under the IPTW approach (aHR 0.88, 95% CI 0.70–1.10). The sub-distribution hazard ratio (sHR) for LRE in the SGLT2i group was 0.89 (95% CI 0.71–1.11) compared with the DPP4i group. Sensitivity analyses using different grace periods to define treatment discontinuation also showed similar results: aHRs of 0.89 (95% CI 0.71–1.11), 0.88 (95% CI 0.71–1.10), and 0.82 (95% CI 0.71–1.11) for grace periods of 45, 90, and 180 days, respectively.

In addition, there were no significant differences between the two groups in stratified analyses according to age, sex, BMI, hypertension, AVT, or ALT level (all p > 0.05) (Table S4). Lastly, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) status was included as an additional covariate in the regression model. Hepatic steatosis was identified using a Fatty Liver Index threshold of ≥60. The prevalence of MASLD was significantly higher in the SGLT2i group (46.1%, 646 cases) than in the DPP4i group (31.4%, 3,457 cases; p < 0.001). As shown in Table S5, the results remained consistent with those of the main analysis.

4DiscussionTo our knowledge, this is the first nationwide study to directly compare the risk of LRE between SGLT2i and DPP4i in the so-called “at-risk population”, namely, patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). We found no significant difference in the risk of LRE between the two groups. Similarly, the risks of secondary outcomes—including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), liver cirrhosis (LC) with or without decompensation, and all-cause mortality—were also comparable between the SGLT2i and DPP4i groups. A similar nonsignificant trend was observed in the stratified analyses.

Several previous studies have investigated the risk of LRE in patients with T2DM receiving SGLT2i. Lee et al. reported a 46% lower risk of HCC associated with SGLT2i use compared with non-use., [19] However, their study design raises concerns about potential bias. Although they attempted to control for immortal time bias by setting the non-user index date to the mid-year of the index year, comparing SGLT2i users with non-users may have introduced induction bias., [30] Liang et al. also observed a significantly lower risk of LRE with SGLT2i use (subdistribution HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.19–0.90) using competing risk analysis., [31] However, their study design is subject to similar limitations. Selection bias may have arisen from enrolling prevalent users as non-users, and the use of a 90-day threshold to define drug users could have led to misclassification bias.

Our findings regarding HCC risk have several strengths compared with previous studies. First, unlike a recent study suggesting that SGLT2i use is associated with a lower risk of LRE compared with DPP4i [32], our study specifically focused on a representative “at-risk” East Asian population—patients with CHB and T2DM. In contrast, Chung et al. included only patients with steatotic liver disease (SLD) and T2DM, in whom the 5-year cumulative incidence of LRE was at most 3%. In our study, this incidence was over 8%, which may partly explain the observed discrepancy. We can therefore cautiously speculate that the potential beneficial effect of SGLT2i might be attenuated in the context of chronic HBV infection. In a similar vein, although T2DM is independently associated with an increased risk of HCC among CHB patients, its relative impact may be weaker than that of other etiologic factors., [33,34] Further studies are needed to identify subgroups more likely to benefit from SGLT2i.

Moreover, a discrepant finding regarding the beneficial effect of SGLT2i, even among patients with SLD and T2DM, was also reported by Jang et al. [35] In that study, although SGLT2i use was associated with a greater degree of NAFLD regression compared to DPP4i, it failed to achieve statistical significance in reducing the risk of LRE relative to DPP4i. Therefore, further well-designed randomized controlled trials are warranted to definitively clarify the relationship between SGLT2i use and HCC risk.

Second, we used a new-user cohort design with DPP4i—a commonly prescribed second-line oral antidiabetic drug—as the active comparator and found no significant difference in HCC risk between the two groups. In contrast, another study using DPP4i as a comparator in a subgroup of HBV-infected patients reported a significantly lower risk of HCC associated with SGLT2i use (aHR 0.32, 95% CI 0.17–0.59)., [20] This discrepancy may be explained by their use of a minimal 1-week cutoff to define drug users in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Lastly, our target trial emulation design provides a more robust framework, comparable to a randomized controlled trial. This approach minimizes bias and enhances causal inference. Additionally, by focusing on patients receiving specific combination therapy (metformin + DPP4i vs. metformin + SGLT2i) and excluding those on other medications, we achieved a clearer and more homogeneous comparison between treatment groups.

SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), known for their weight-reducing effects, have shown promise in ameliorating hepatic inflammation and fibrosis., [36–39] Preclinical studies suggest that SGLT2i may suppress HCC cell proliferation and tumorigenesis through mechanisms such as inhibiting glucose uptake and cellular growth or reducing tumor angiogenesis., [40–43] Although DPP4i may have a smaller impact on LRE—particularly those related to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—due to their minimal effect on body weight, [35,44] it may still influence HCC risk., [45,46] DPP4i can increase glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) levels, potentially reducing HCC risk by promoting lymphocyte chemotaxis and suppressing signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation. Several clinical studies have reported potential benefits of DPP4i in preventing HCC among diabetic patients with chronic HBV [47] or HCV infection., [48] Considering these findings alongside ours, the effects of SGLT2i on HCC risk may be comparable to those of DPP4i. Future studies are warranted to further investigate this relationship and strengthen the evidence base., [49]

Our study has several limitations. First, the NHIS database has inherent constraints regarding data comprehensiveness and its reliance on administrative diagnostic codes. Consequently, identifying CHB, T2DM, and LRE based on these codes introduces the potential for coding errors by healthcare providers. Nevertheless, in the Republic of Korea, diagnostic codes are essential for the reimbursement of prescribed medications, which likely minimizes this concern within our study cohort. Second, our analysis relied on prescription records to identify treatment discontinuation or switching. This approach may not fully capture actual medication adherence. To address this limitation, we performed sensitivity analyses using different grace periods for defining treatment discontinuation, and the results remained consistent. Third, our findings reflect prescribing patterns during the study period, when SGLT2i were primarily used as second- or third-line agents. As SGLT2i are now widely recommended as first-line therapy for T2DM patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, or chronic kidney disease, the direct extrapolation of our results to current treatment strategies may be limited. Additionally, due to the strict and selective National Health Insurance reimbursement criteria for diabetes medications in Korea, real-world practice patterns in our cohort may differ from international guidelines. Furthermore, we were unable to include GLP-1 receptor agonists or dual GLP-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonists as comparators, which warrants further research. Finally, because this study focused on the Korean population, the generalizability of our findings to other racial or ethnic groups remains to be validated in future investigations.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, this target trial–emulated study found no significant difference in the risk of LRE between patients receiving SGLT2i and those receiving DPP4i. Well-designed randomized controlled trials are needed to definitively clarify the relationship between SGLT2i use and LRE risk.

Author contributionsB.Yoon and J.Oh researched data, contributed to discussion, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. B.K.Kim and J–H.Yoon researched data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. H.Park and J.Lee contributed to the discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. B.K.Kim and J–H.Yoon are the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

None.

We would like to thank Editage (https://www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing. This study used the National Health Insurance Service database (NHIS-2023-4-002).

Funding: This study was supported by a faculty research grant of Yonsei University College of Medicine (6-2024-0615).