The case of a 64 year old female patient is presented who has treated herself for 9 months with various Indian Ayurvedic herbal products for her vitiligo and experienced a causally related severe hepatotoxicity (ALT, 601 U/L; AST, 663 U/L; Bilirubin, 5.0 mg/dL). After discontinuation, a rapid improvement was observed. Causality assessment with the updated CIOMS (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences) scale showed a probable causality (+8 points) for Bakuchi tablets containing extracts from Psoralea corylifolia leaves with psoralens as ingredients, as the primary candidate causing the hepatotoxic reaction. The degree of probability was lower with +6 points for other used herbs: Khadin tablets containing extracts from Acacia catechu leaves; Brahmi tablets containing Eclipta alba or Bacopa monnieri; and Usheer tea prepared from Vetivexia zizaniodis. The case is the first report of Indian Ayurvedic herbal products being potentially hepatotoxic in analogy to some other herbs.

Rare hepatotoxicity has been ascribed to drugs and dietary supplements (DDS), but a vigorous causality evaluation using a quantitative approach has not always been performed.1-6 Causality assessment is crucial in face of incomplete documentation of cases; the failure of exclusion of other causes for the observed liver disease; and the co-medication with other chemically defined drugs as well as dietary supplements.3-6

We present a well documented case of a female patient with toxic liver disease in temporal and causal relationship with the use of various Indian Ayurvedic herbal products as treatment for vitiligo.

Case ReportClinical courseThe 64 year old female patient is of Indian origin, who has lived in Germany for the past 4 years except when she visited India for 2 weeks in 11/2003. She is a business clerk in a publishing company and was always healthy but noticed depigmentation of her hands starting 2003. The diagnosis of vitiligo was established by a dermatologist. In 2004 she received a laser therapy for her vitiligo over a 9 months period, but improvement was not apparent. Ultraviolett-A (UVA) treatment was subsequently initiated without concomitant drug therapy, and there was again no improvement of her vitiligo.

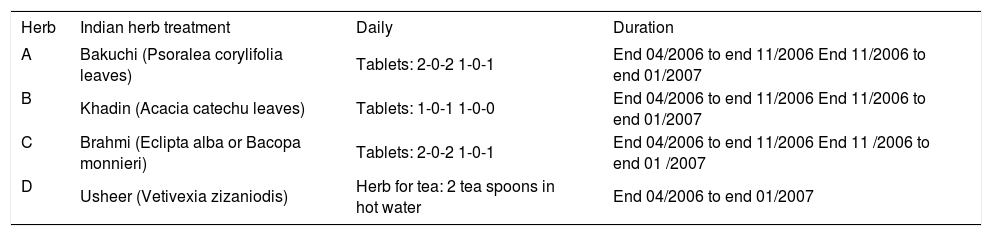

The patient then searched the internet for an alternative therapy of vitiligo in China as well as in India and contacted one of the Indian Ayurvedic clinics specialized for vitiligo. The physician in charge asked about her past medical history and sent her tablets and tea. They were to be taken for 2 years and were regularly supplied by the clinic. The herbs were named Bakuchi (here herb A), Khadin (herb B), Brahmi (herb C), and Usheer (herb D). Treatment was initiated at the end of 4/2006 with a total of 10 tablets daily (Table 1). Moreover, she was told to apply locally 1 grinzed tablet of Bakuchi once a week. She was also instructed to use the Usheer herb to prepare a tea by boiling 2 cups of water with 2 tea spoons of the herb as long as half of the water has evaporated, and the resulting 1 cup of tea she was advised to drink once daily. An additional UVA treatment was not recommended. In the further course of the treatment the tablets and the tea failed to positvely influence her vitiligo, but the tea improved her meteorism.

Treatment schedule with Indian Ayurvedic herbal products.

| Herb | Indian herb treatment | Daily | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Bakuchi (Psoralea corylifolia leaves) | Tablets: 2-0-2 1-0-1 | End 04/2006 to end 11/2006 End 11/2006 to end 01/2007 |

| B | Khadin (Acacia catechu leaves) | Tablets: 1-0-1 1-0-0 | End 04/2006 to end 11/2006 End 11/2006 to end 01/2007 |

| C | Brahmi (Eclipta alba or Bacopa monnieri) | Tablets: 2-0-2 1-0-1 | End 04/2006 to end 11/2006 End 11 /2006 to end 01 /2007 |

| D | Usheer (Vetivexia zizaniodis) | Herb for tea: 2 tea spoons in hot water | End 04/2006 to end 01/2007 |

She felt well until the beginning of 10/2006 when she first begun to notice pruritus. The subsequent clinical course included symptoms such as loss of appetite, fatigue, nausea and vomiting several times per week. Her urine became dark in 11/2006 and the stool light in 1/2007. Treatment with omeprazole was started, but her symptoms persisted. In 11/2006 she contacted the clinic in India again and inquired about possible side effects of the recommended treatment. They were denied. At the end of 11/2006 she reduced the daily intake of the tablets by half and experienced the disappearence of her pruritus, but the other symptoms persisted.

At the end of 1/2007 she consulted her family physician who examined her and noticed jaundice in the sclera of her eyes. Since a herb induced liver disease was assumed, she discontinued her medications on 29/1/2007 and was placed in the ward of our hospital for further evaluation. Our physical examination revealed no pathological findings except for jaundice in the sclerae of her eyes, the vitiligo of her hands, and some tenderness in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. RR 110/60 mmHg, pulse rate 75/min. Body weight 54 kg, height 167 cm.

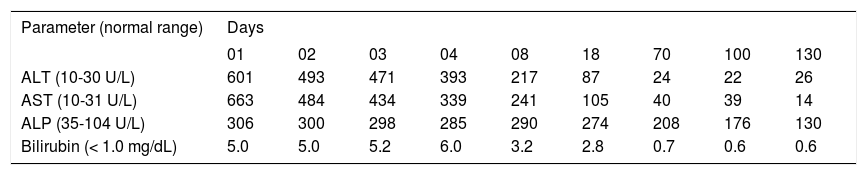

The symptoms were regredient in the further course without any specific treatment as were the initially high values of laboratory tests (Table 2). The patient was discharged after 8 days.

Temporal course of various parameters following discontinuation of the use of the Indian Ayurvedic herbal products.

| Parameter (normal range) | Days | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 08 | 18 | 70 | 100 | 130 | |

| ALT (10-30 U/L) | 601 | 493 | 471 | 393 | 217 | 87 | 24 | 22 | 26 |

| AST (10-31 U/L) | 663 | 484 | 434 | 339 | 241 | 105 | 40 | 39 | 14 |

| ALP (35-104 U/L) | 306 | 300 | 298 | 285 | 290 | 274 | 208 | 176 | 130 |

| Bilirubin (< 1.0 mg/dL) | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 6.0 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

ALT: denotes alanine aminotransaminase. ALP: alkaline phosphatase. AST: aspartate aminotransaminase.

Normalization was achieved for ALT and bilirubin after 70 days and for AST after 130 days (Table 2). Prolonged normalization of 1 year was observed for ALP. ANA titers remained stable at 1:320 up to day 70, declined to 1:100 on day 100, and were in the normal range (1: < 100) on day 130.

Laboratory dataThe initial values were as follows: alanine amino-transferase (ALT) 601 IU/L (normal 10-30), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 663 IU/L (normal 10-31), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 304 IU/L (normal 35-104), y-glutamyl transpeptidase (y-GT) 421 IU/L (normal < 39), glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) 26.1 IU/L (normal < 4.8), total bilirubin (TB) 5.0 mg% (normal < 1.0), choline esterase (CHE) 3,555 IU/L (normal 5,320 - 12,920), INR 1.43 (normal < 1.31), lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) 292 IU/L (normal < 214), α-amylase 146 IU/l (normal 28-100), lipase 84 IU/L (normal 13-60), C-reactive protein (CRP) 0.78 mg% (normal < 0.50), ferritin 238 ng/mL (normal 15150), total protein 2.86 g/dL (normal 4.3-5.1), α1-globulins 0.13 g/dL (normal 0.1 - 0.2), α2-globulins 0.41 g/dL (normal 0.5-0.8), β-globulins 0.60 g/dL (normal 0.60-0.90), γ-globulins 0.89 g/dL (normal 0.60-1.10). In the normal range were transferrin, TRF saturation, α1-antitrypsin, IgG, IgA, IgM, Fe, Cu, cerulo-plasmin, free T3, free T4, TSH, and complete blood count.

Additional results included anti-HAV-IgG + IgM > 60 mU/L (normal < 20) and negative titers for anti-HAV-IgM, HBs-antigen, anti-HBc IgG + IgM, anti-HCV-IgG + IgM, anti-HEV-IgG + IgM. ANA-immunofluorescence test 1:320 (normal < 1:100) and negative titers for SS-A, SS-B, Sm, RNP-sm, Scl 70, Jo-1, anti-dsDNS antibodies, ASMA, AMA, LKM-1-antibodies, SLA / LP antibodies, p-ANCA, c-ANCA. Anti-CMV-IgG 118 U/mL (normal < 15), anti-CMV-IgM negative, anti-EBV-VCA-IgG positive, anti-EBV-VCA-IgM negative, anti-EBV-EA-IgG positive, anti-EBV-EBNA1-IgG positive, anti-HSV1-IgG and-IgM negative, anti-HSV2-IgG and-IgM negative, anti-VZV-IgG positive, anti-VZV-IgM negative, anti-Endomysium-IgA and-IgG negative, anti-Gliadin-IgA and-IgG negative.

The urinary analysis was without pathological findings except for ketone 15 mg/dL (normal < 5), bilirubin 1.0 mg/dL, and urobilinogen 8.0 mg/dL (normal < 1.0). Urinary copper excretion of 24 hours was normal.

Technical dataThe ultrasonography showed only some inhomogeneity of the liver with normal findings of the gallbladder, intra-and extrahepatic bile ducts, pancreas, spleen and kidneys. Upon colour Doppler sonography there was no thrombosis or enlargement of the V. cava inferior and no thrombosis of the portal vein. The ecg was normal without arrhythmias, and the transthoracal ultrasound examination of the heart showed no pathological findings and no signs of cardiac insufficiency.

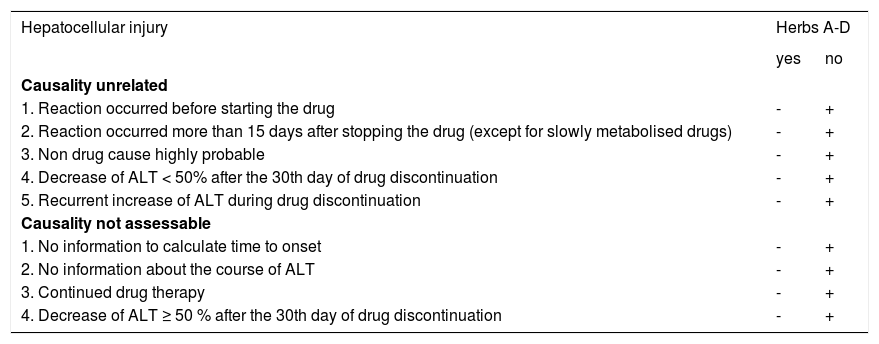

Classification of hepatotoxicityFor subsequent causality assessment the determination of the respective type of hepatotoxicity is essential. This requires lab tests rather than liver histology.3,7-9 Differentiation between hepatocellular and cholestatic (± hepatocellular) injury is achieved by measurements of serum activities of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (Table 3).3 In the present case ALT activity was initially 601 IU/L corresponding to the 19.4 multiple of the upper limit of the normal range of 31 IU/l, whereas ALP activity was initially 304 IU/l corresponding to the 2.9 multiple of the upper limit of the normal range of 104 IU/L. Since the ratio (R) of ALT : ALP is 7.7, our patient has a clear hepatocellular type of hepatotoxicity rather than a cholestatic or cholestatic - hepatocellular one where the R values are < 2 or 2 < R < 5, respectively.

Pre-test. Bakuchi (herb A), Khadin (herb B), Brahmi (herb C), Usheer (herb D). Drugs or dietary supplements (DDS) to be assessed.

| Hepatocellular injury | Herbs A-D | |

|---|---|---|

| yes | no | |

| Causality unrelated | ||

| 1. Reaction occurred before starting the drug | - | + |

| 2. Reaction occurred more than 15 days after stopping the drug (except for slowly metabolised drugs) | - | + |

| 3. Non drug cause highly probable | - | + |

| 4. Decrease of ALT < 50% after the 30th day of drug discontinuation | - | + |

| 5. Recurrent increase of ALT during drug discontinuation | - | + |

| Causality not assessable | ||

| 1. No information to calculate time to onset | - | + |

| 2. No information about the course of ALT | - | + |

| 3. Continued drug therapy | - | + |

| 4. Decrease of ALT ≥ 50 % after the 30th day of drug discontinuation | - | + |

The term drug refers basically to any synthetic drug, herbal drug, and dietary supplement including the herbal one. For differentiation of the hepatocellular, cholestatic or mixed form of hepatotoxicity caused by drugs and dietary supplements (DDS), serum activities of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) are measured on the day the diagnosis of DDS hepatotoxicity is suspected. Each activity is expressed as multiple of the upper limit of the normal range (N), and the ratio (R) of ALT : ALP is calculated. Liver injury is (1) hepatocellular, when ALT > 2N alone or R ≥ 5, (2) cholestatic when there is an increase of ALP > 2N alone or when R ≤ 2, and (3) of the mixed type when ALT > 2N, ALP is increased and 2 ≥ R ≥ 5. When at least one question is answered with yes, causality is unrelated or not assessable, respectively. The pre-test and the subsequent main-test evaluate the hepatocelluar injury separately from the cholestatic (± hepatocellular) one. In the present case a hepatocellular type of hepatotoxicity was found. Hence, the pre-test for hepatocellular injury was used.

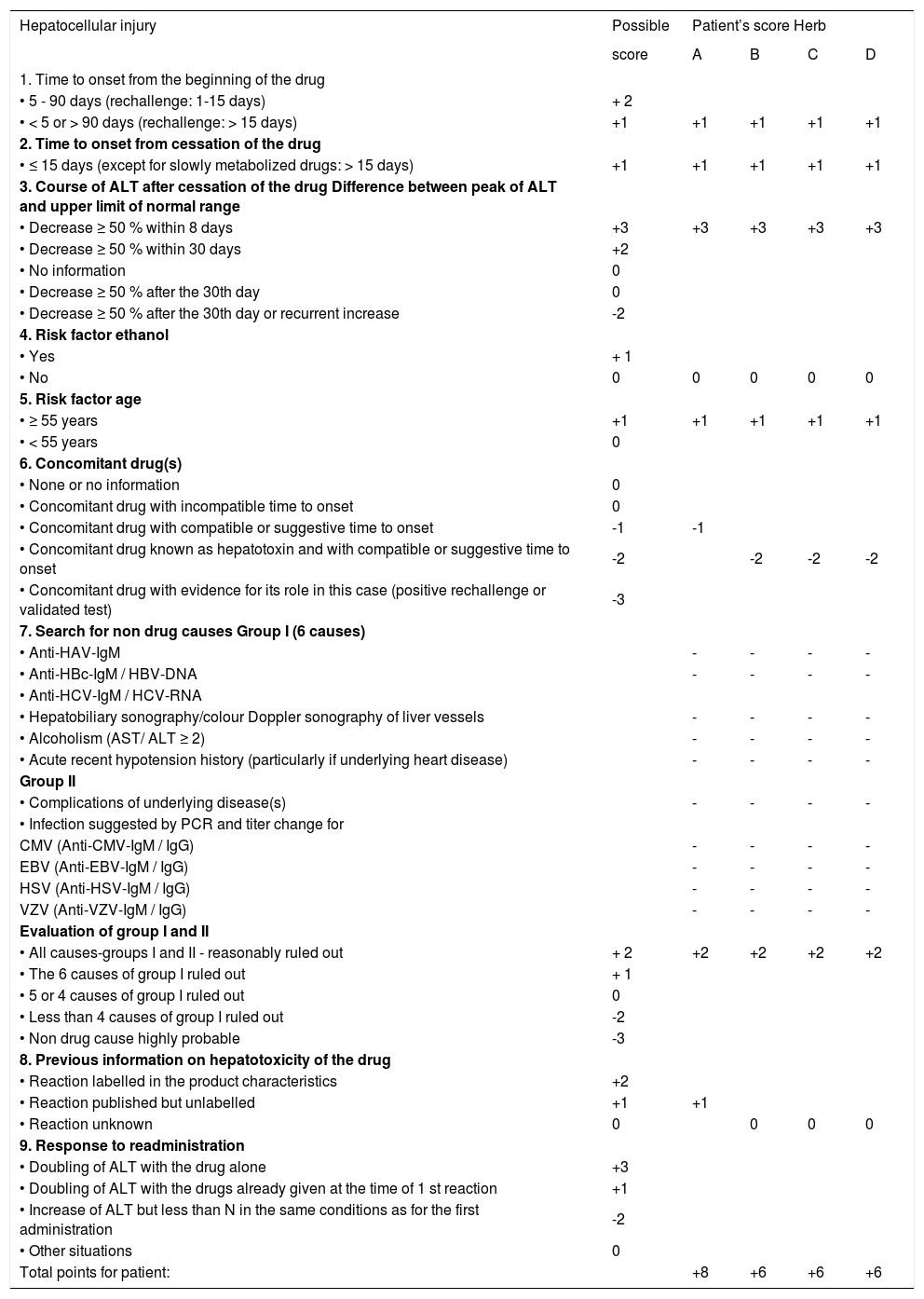

Basically, the algorithm of causality assessment proceeds via the pre-test and main-test specifically either for the hepatocellular injury or the cholestatic (± hepatocellular) type of hepatotoxicity, whereas the post-test is identical for all entities.3 The pre-test is qualitatively oriented (Table 3)3 and based on qualitative criteria described in the evaluation by the scale of CIOMS (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences).7-9 The subsequent main-test represents the quantitative causality assessment (Table 4) and is based on the CIOMS scale,8,9 updated regarding actual diagnostic procedures.3 The post-test is of qualitative nature (Table 5).3

Main-test. Bakuchi (herb A), Khadin (herb B), Brahmi (herb C), Usheer (herb D). Drugs or dietary supplements (DDS) to be assessed.

| Hepatocellular injury | Possible | Patient’s score Herb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| score | A | B | C | D | |

| 1. Time to onset from the beginning of the drug | |||||

| • 5 - 90 days (rechallenge: 1-15 days) | + 2 | ||||

| • < 5 or > 90 days (rechallenge: > 15 days) | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 |

| 2. Time to onset from cessation of the drug | |||||

| • ≤ 15 days (except for slowly metabolized drugs: > 15 days) | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 |

| 3. Course of ALT after cessation of the drug Difference between peak of ALT and upper limit of normal range | |||||

| • Decrease ≥ 50 % within 8 days | +3 | +3 | +3 | +3 | +3 |

| • Decrease ≥ 50 % within 30 days | +2 | ||||

| • No information | 0 | ||||

| • Decrease ≥ 50 % after the 30th day | 0 | ||||

| • Decrease ≥ 50 % after the 30th day or recurrent increase | -2 | ||||

| 4. Risk factor ethanol | |||||

| • Yes | + 1 | ||||

| • No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5. Risk factor age | |||||

| • ≥ 55 years | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 |

| • < 55 years | 0 | ||||

| 6. Concomitant drug(s) | |||||

| • None or no information | 0 | ||||

| • Concomitant drug with incompatible time to onset | 0 | ||||

| • Concomitant drug with compatible or suggestive time to onset | -1 | -1 | |||

| • Concomitant drug known as hepatotoxin and with compatible or suggestive time to onset | -2 | -2 | -2 | -2 | |

| • Concomitant drug with evidence for its role in this case (positive rechallenge or validated test) | -3 | ||||

| 7. Search for non drug causes Group I (6 causes) | |||||

| • Anti-HAV-IgM | - | - | - | - | |

| • Anti-HBc-IgM / HBV-DNA | - | - | - | - | |

| • Anti-HCV-IgM / HCV-RNA | |||||

| • Hepatobiliary sonography/colour Doppler sonography of liver vessels | - | - | - | - | |

| • Alcoholism (AST/ ALT ≥ 2) | - | - | - | - | |

| • Acute recent hypotension history (particularly if underlying heart disease) | - | - | - | - | |

| Group II | |||||

| • Complications of underlying disease(s) | - | - | - | - | |

| • Infection suggested by PCR and titer change for | |||||

| CMV (Anti-CMV-IgM / IgG) | - | - | - | - | |

| EBV (Anti-EBV-IgM / IgG) | - | - | - | - | |

| HSV (Anti-HSV-IgM / IgG) | - | - | - | - | |

| VZV (Anti-VZV-IgM / IgG) | - | - | - | - | |

| Evaluation of group I and II | |||||

| • All causes-groups I and II - reasonably ruled out | + 2 | +2 | +2 | +2 | +2 |

| • The 6 causes of group I ruled out | + 1 | ||||

| • 5 or 4 causes of group I ruled out | 0 | ||||

| • Less than 4 causes of group I ruled out | -2 | ||||

| • Non drug cause highly probable | -3 | ||||

| 8. Previous information on hepatotoxicity of the drug | |||||

| • Reaction labelled in the product characteristics | +2 | ||||

| • Reaction published but unlabelled | +1 | +1 | |||

| • Reaction unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9. Response to readministration | |||||

| • Doubling of ALT with the drug alone | +3 | ||||

| • Doubling of ALT with the drugs already given at the time of 1 st reaction | +1 | ||||

| • Increase of ALT but less than N in the same conditions as for the first administration | -2 | ||||

| • Other situations | 0 | ||||

| Total points for patient: | +8 | +6 | +6 | +6 | |

The term drug refers basically to any synthetic drug, herbal drug, and dietary supplement including the herbal one. In the section 7 (search for non drug causes) the symbol of - denotes that the parameter has been evaluated and the result was negative. Total points: ≤ 0 = causality excluded. 1-2 = causality unlikely. 3-5 = causality possible. 6-8 = causality probable. >8 = causality highly probable. ALT: denotes alanine aminotransferase. AST: aspartate aminotransferase. CMV: cytomegalovirus. EBV: Epstein Barr virus. HAV: hepatitis A virus. HBV: hepatitis B virus. HCV: hepatitis C virus. HSV: herpes simplex virus. N: normal range (upper limit). PCR: polymerase chain reaction. VZV: varicella zoster virus.

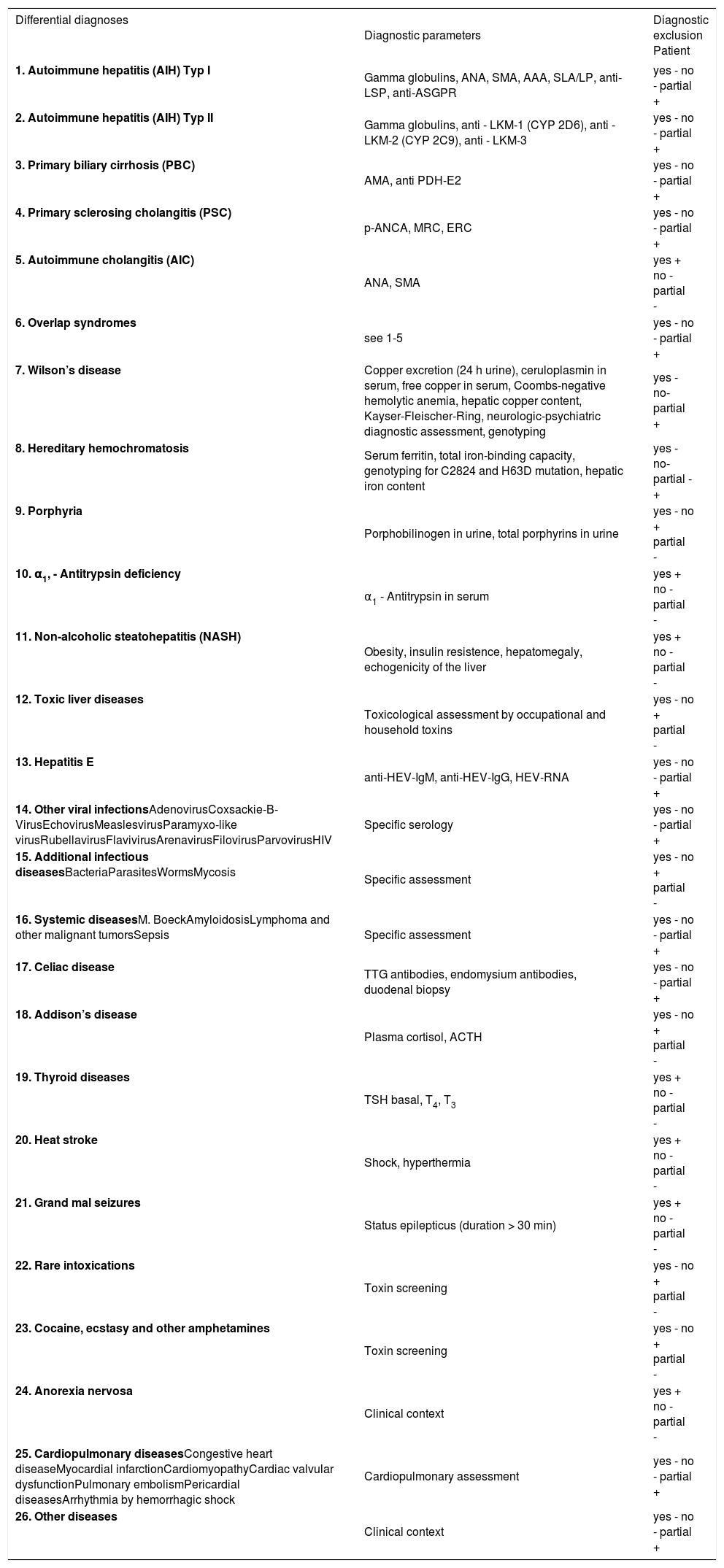

Post-test.

| Differential diagnoses | Diagnostic parameters | Diagnostic exclusion Patient |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) Typ I | Gamma globulins, ANA, SMA, AAA, SLA/LP, anti-LSP, anti-ASGPR | yes - no - partial + |

| 2. Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) Typ II | Gamma globulins, anti - LKM-1 (CYP 2D6), anti - LKM-2 (CYP 2C9), anti - LKM-3 | yes - no - partial + |

| 3. Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) | AMA, anti PDH-E2 | yes - no - partial + |

| 4. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) | p-ANCA, MRC, ERC | yes - no - partial + |

| 5. Autoimmune cholangitis (AIC) | ANA, SMA | yes + no - partial - |

| 6. Overlap syndromes | see 1-5 | yes - no - partial + |

| 7. Wilson’s disease | Copper excretion (24 h urine), ceruloplasmin in serum, free copper in serum, Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia, hepatic copper content, Kayser-Fleischer-Ring, neurologic-psychiatric diagnostic assessment, genotyping | yes - no-partial + |

| 8. Hereditary hemochromatosis | Serum ferritin, total iron-binding capacity, genotyping for C2824 and H63D mutation, hepatic iron content | yes - no-partial - + |

| 9. Porphyria | Porphobilinogen in urine, total porphyrins in urine | yes - no + partial - |

| 10. α1, - Antitrypsin deficiency | α1 - Antitrypsin in serum | yes + no - partial - |

| 11. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) | Obesity, insulin resistence, hepatomegaly, echogenicity of the liver | yes + no - partial - |

| 12. Toxic liver diseases | Toxicological assessment by occupational and household toxins | yes - no + partial - |

| 13. Hepatitis E | anti-HEV-IgM, anti-HEV-IgG, HEV-RNA | yes - no - partial + |

| 14. Other viral infectionsAdenovirusCoxsackie-B-VirusEchovirusMeaslesvirusParamyxo-like virusRubellavirusFlavivirusArenavirusFilovirusParvovirusHIV | Specific serology | yes - no - partial + |

| 15. Additional infectious diseasesBacteriaParasitesWormsMycosis | Specific assessment | yes - no + partial - |

| 16. Systemic diseasesM. BoeckAmyloidosisLymphoma and other malignant tumorsSepsis | Specific assessment | yes - no - partial + |

| 17. Celiac disease | TTG antibodies, endomysium antibodies, duodenal biopsy | yes - no - partial + |

| 18. Addison’s disease | Plasma cortisol, ACTH | yes - no + partial - |

| 19. Thyroid diseases | TSH basal, T4, T3 | yes + no - partial - |

| 20. Heat stroke | Shock, hyperthermia | yes + no - partial - |

| 21. Grand mal seizures | Status epilepticus (duration > 30 min) | yes + no - partial - |

| 22. Rare intoxications | Toxin screening | yes - no + partial - |

| 23. Cocaine, ecstasy and other amphetamines | Toxin screening | yes - no + partial - |

| 24. Anorexia nervosa | Clinical context | yes + no - partial - |

| 25. Cardiopulmonary diseasesCongestive heart diseaseMyocardial infarctionCardiomyopathyCardiac valvular dysfunctionPulmonary embolismPericardial diseasesArrhythmia by hemorrhagic shock | Cardiopulmonary assessment | yes - no - partial + |

| 26. Other diseases | Clinical context | yes - no - partial + |

AAA: anti-actin antibodies. AMA: antimitochondrial antibodies. ANA: denotes antinuclear antibodies. ASGPR: Asialo-glycoprotein-receptor. CYP: cytochrome P450. DPH: pyruvat dehydrogenase. ERC: endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. HEV: hepatitis E virus. HIV: human immunodeficiency virus. LKM: liver kidney microsomes. LP: liver-pancreas antigen. LSP: liver specific protein. MRC: magnetic resonance cholangiography. p-ANCA: perinuclear antineutrophile cytoplasmatic antibodies. SLA: soluble liver antigen. SMA: smooth musle antibodies. TSH: thyroid - stimulating hormone. TTG: tissue transglutaminase.

For the patient in this report the pre-test for hepatocellular injury had to be applied, and each of the used herbs was evaluated separately (herb A: Bakuchi; herb B: Khadin; herb C: Brahmi; and herb D: Usheer). For all 4 herbs there is not one single item with the answer “yes”, indicating that causality may basically be related and assessable (Table 3).

Main-testWith the main-test for hepatocellular injury each of the 4 herbs (A-D) has to be evaluated separately and quantitatively, and the respective answers are scored with points ranging from -3 to +3 (Table 4). Of particular interest is the item 3 regarding the course of ALT after cessation of the drug (Table 4). Our patient showed an ideal decline of ALT by > 50 % within 8 days, rendering as much as +3 points.

The total number of the score for each herb shows the grade of causality: total points < 0 causality excluded, 1-2 points not probable, 3-5 points, possible, 6-8 points probable, and > 8 points very probable. Herb A reached a total of +8 points, whereas the remaining herbs B-D got +6 points each. Therefore, the most probable causality has to the ascribed to herb A (Bakuchi), whereas the probablitiy is lower for herbal products B (Khadin), C (Brahmi), and D (Usheer).

Post-testThe qualitative post-test reassures that the most important differential diagnosis have been considered (Table 5). In the present case, only some other causes were excluded, since the diagnosis of reversible herbal hepatotoxicity was clear within a short time. At any rate, the post-test is obligatory in any case of beginning or ongoing acute liver failure to establish a final diagnosis, possibly overlooked or not considered in the course of evaluation by the main-test.

DiscussionThe analysis of the present case indicates that medication with several Indian Ayurvedic herbal products used for treatment of vitiligo carries the risk of severe hepatotoxicity (Table 1-2). The structured causality assessment showed that Bakuchi given as tablets containing extracts from Psoralea corylifolia leaves with psoralens as ingredients is the most probable candidate having caused the hepatotoxic reaction (Table 3). The degree of probability is lower for the other used herbs: Khadin taken as tablets containing extracts from Acacia catechu leaves, Brahmi tablets containing Eclipta alba or Bacopa monnieri, and the herbal Usheer tea prepared from Vetivexia zizaniodis. This report is in line with the oberservation that another Indian Ayurvedic herbal product, Liv 52, which comprises 6 herbs, was hepatotoxic in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis and has been immediately withdrawn from the US market.10 It is concluded that Indian Ayurvedic herbal products may exert similar hepatotoxic risks as other dietary supplements and chemically defined drugs.

Our patient took Psoralea corylifolia which is a constituent of Bakuchi and contains psoralens,11 known to be potentially hepatotoxic in rare instances.12 Psoralens are naturally occurring furocoumarins11,13 and potent inhibitors of cytochrome P450.14-16 This leads to impaired drug metabolism in humans,17 findings which may explain the hepatotoxicity not only of psoralens but also of other comedicated dietary supplements in our patient. Various constituents have been described for Acacia catechu,18 Eclipta alba,19,20 Bacopa monnieri21 or Vetivexia zizaniodis,22 but detailed information regarding hepatotoxic risks in humans is not available. Ayurvedic herbal products may also contain heavy metals23 as in asiatic herbal preparations.24 Other problems may include misidentification as with Chinese herbal products,25 since in the present case the herb provider declared to the patient Eclipta alba as ingredient in Brahmi (Table 1), whereas the internet information noticed Bacopa monnieri as its constituent.26

Of interest is the observation of increased ANA titers in our patient, with stable titers in the further course after cessation of the herbal treatment under conditions of subsequently normalized serum ALT activities. In the present case there was no clinical or biochemical evidence for an associated autoimmune hepatitis, a condition previously described for various drugs but not for psoralens.12 The increased ANA titers can be ascribed to the vitiligo-associated multiple autoimmune disease which may also include systemic lupus erythematodes.27 Nevertheless, an intercalation of psoralens with DNA is described13 which by itself may trigger ANA formation. In the present case, ANA titer normalized 130 days after cessation of the Ayurvedic product, suggesting that the previously increased ANA titers were more likely attributed to the herbal drug than to vitiligo itself.

Vitiligo is a common skin disease that is treated very successfully in the Western medicine with once or twice weekly applications of psoralens and UV-A (PUVA). According to Western standards, the single application of psoralens is limited to 2 hours before UVA treatment,28 yielding low weekly doses of psoralens. In the present case an Indian Ayurvedic therapy was used with several herbal products one of which contained psoralens. The herbal therapy was recommended day by day for a total of 2 years, but symptoms of toxic liver disease emerged already after 7 months of treatment. It is not excluded that psoralens may have become hepatotoxic due to accumulation. Co-medication of drugs substantially increases the risk of hepatotoxicity,29 a situation applicable to the present case treated with multiple herbal products (Table 1). Finally, concomitant UVA treatment was neither recommended to nor discussed with the patient, therefore it was not done.

The algorithm of structured causality assessment using the pre-test, main-test and post-test was applied in this case (Table 3-Table 4Table 5) and should be done in any other patient with suspected hepatotoxicity by drugs and dietary supplements (DDS).3 This step-by-step approach may add consistency to the diagnostic process, thereby establishing the degree of probability, and excluding virtually all causes of liver disease independent of DDS. The consecutive reporting to the health care agencies for pharmaco-vigilance purposes and to scientific journals to be published as case reports should provide item by item in all tests and separately for each of the used DDS to ensure transparency and facilitate reassessment by others.3,30

The main-test was used for causality assessment in the present case (Table 3) and in previous case studies.5,6 It represents the updated form of the structured quantitative CIOMS scale.3 An update was necessary for reasons of precision and actualization. In the main-test there are no more qualitative items (Table 3) as in the CIOMS scale.8 Confirmation of the exclusion of hepatitis B and C was more specified regarding antibody assessment and hepatitis B DNA and hepatitis C RNA determination.3 Similarly, the use of colour Doppler sonography for assessment of hepatic vessels has been added. For the exclusion of CMV, EBV, HSV, and VZV the required parameters are presented. A modification of the CIOMS scale has recently been considered to be appropriate, but specific suggestions were not presented.31

Despite some criticism of the CIOMS scale,31 it should be kept in mind that the scale has been well validated (sensitivity 86%, specificity 89%, positive predictive value 93%, and negative predictive value 78%), with no overlap between the cases and the controls.9 It is also widely used.1-3,5,6,31-33 The CIO-MS scale has been established by experts from France, Denmark, Germany, Italy, UK and the USA8,9 and was based on the results of re-challenge tests9 considered as gold standard for the diagnosis of DDS hepatotoxicity.3,9 The recent criticism of the CIOMS scale was based on problematic test-retests and interrater reliabilities.31 The shortcomings of this study were the retrospective evaluation of cases going back to 1994, and missing or incomplete data. Information on death, fulminant hepatic failure, and dechallenge was not always available, and other competing causes may not have been always excluded. There were also varying qualifying criteria for notable liver dysfunction in the different groups of drugs. Other open questions relate to possible problems of using a subset of case report forms, and of information exchange between the site of the principal investigator and the involved assessors who had no previous experience with the CIOMS scale.31 Overall, the suggestion that causality should only be assessed by physicians at arm’s length from the case31 is in line with our proposals.3,30 This has also been done in the present case report, assessing and presenting item by item.

In summary, Indian Ayurvedic herbal products used for vitiligo may be hepatotoxic and exert a high risk/benefit ratio. There is no recommendation for this particular treatment that has not been substantiated by Western standards.