Background and aims. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill patients (SSC-CIP) is a relatively new previously unrecognized entity which may lead to severe biliary disease with rapid progression to cirrhosis. We present for the first time a case series of patients with rapidly progressive SSC-CIP requiring aggressive intensive care treatment following major burn injury.

Results. SSC-CIP was diagnosed in 4 consecutive patients hospitalized due to major burn injuries at our Intensive Care Unit (ICU). SSC-CIP was diagnosed when ERCP (n = 1) or MRCP (n = 3) demonstrated irregular intrahepatic bile ducts with multiple strictures and dilatations and, when a liver biopsy (n = 3) demonstrated severe cholestasis and bile duct damage. All patients were males; none of whom had pre-existing liver disease. Ages: 18-56 y. All patients suffered from severe (grade 2-3) burn injuries with total burn surface area ranging from 35 to 95%. Mean length of ICU hospitalization was 129.2 ± 53.0 days. All patients required mechanical ventilation (with a mean PEEP of 8.4 ± 2.1 cm H2O) and the administration of catecholamines for hemodynamic stabilization. All patients demonstrated severe cholestasis. Blood cultures and cultures from drained liver abscesses grew hospital acquired multiple resistant bacteria. Liver cirrhosis developed within 12 months. One patient underwent orthotopic liver transplantation. Two patients (50%) died. In conclusion, SSC-CIP following major burn injury is a rapidly progressive disease with a poor outcome. Liver cirrhosis developed rapidly. Awareness of this grave complication is needed for prompt diagnosis and considerations of a liver transplantation.

Secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC) is a chronic cholestatic biliary disease, characterized by inflammation, obliterative fibrosis of the bile ducts, stricture formation and progressive destruction of the biliary tree that leads to biliary cirrhosis.1 The most frequently described causes of SSC are longstanding biliary obstruction, surgical trauma to the bile duct and ischemic injury to the biliary tree in liver allografts.1 SSC in critically ill patients (SSCCIP) requiring aggressive intensive care treatment is a largely unrecognized new form of SSC, associated with rapid progression to liver cirrhosis. The mechanisms leading to the cholangiopathy in critically ill patients are widely unknown; however, it is likely mediated through ischemic injury to the bile ducts.1 Unlike hepatic parenchyma, which depends on a dual blood supply from the hepatic artery and portal vein, the biliary system depends only on its arterial supply for viability.2 Arterial hypotension of the peribiliary vascular plexus causes ischemic injury of the bile duct epithelium.1 The available clinical data indicate that ischemic injury to the intrahepatic biliary tree followed by bacterial colonization leading to destructive biliary changes may be one of the earliest events in the development of this severe form of SSC-CIP.3 These patients usually have no prior history of biliary disease or liver disease and no evidence of a pathological process or injury that has obviously caused obstruction of the bile duct.4–10 The clinical and radiological manifestations reflect cholestasis.4–10 Cholangiographic findings resemble those of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Therapeutic options for most forms of SSC-CIP are limited, and patients who do not undergo transplantation have rapid disease progression and poor outcome.1,11 Current understanding and management of SSC-CIP is limited. Only 8 patients with SSC–CIP following major burn injury were described previously.5,8,10,11 We present for the first time a case series of rapidly progressive SSC–CIP requiring aggressive intensive care treatment following major burn injury. The radiologic, endoscopic, medical and surgical treatments as well as the clinical course and outcome of this pathology are discussed.

Material and MethodsPatientsBetween January 2008 and August 2013, 4 critically ill patients were diagnosed by either endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and liver biopsy as having SSC-CIP at the ICU of the Sheba Medical Center, Israel. All patients underwent treatment in ICU following major burn injury with the necessity of aggressive intensive care treatment including mechanical ventilation and vasopressor therapy. None of the patients had recorded evidence of pre-existing hepatobiliary diseases including biliary obstruction, intraductal stones, or surgical biliary trauma or biochemical abnormalities based on the normal cholestatic laboratory parameters prior to ICU admission. As assessed by color-assisted duplex sonography or abdominal CT scan, thrombosis or obstruction of the hepatic veins and portal vein were ruled out and the hepatic artery showed patency in all patients. All pertinent data were extracted from patient charts. The study was approved by our local ethics committee.

Criteria for diagnosis of SSC-CIP and clinical dataPatients with SSC-CIP were identified retrospectively by reviewing the MRCP, ERCP and liver biopsy database and patient charts. SSC–CIP was diagnosed when ERCP or MRCP demonstrated an irregular bile duct system with typical appearance of irregular intrahepatic bile ducts with multiple strictures and dilatations and liver biopsy demonstrating severe cholestasis, dilated septal bile ducts and degenerative changes in epithelial bile ducts. Hepatic abscess and segmental liver necrosis/infarction were diagnosed by abdominal ultrasound and tri-phasic CT.

All patient charts were studied to record clinical data including % of body surface area and degree of the burn injury, the indications for ICU admission, laboratory data including serum liver enzyme level, duration of ICU stay, and ICU-based interventions such as mechanical ventilation and duration, which might have effects on liver hemodynamics [positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)], vasopressor therapy, renal replacement therapy, septic episodes, blood cultures, antibiotic treatment and outcome.

Histological evaluation of liver biopsiasRoutine hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stain and Masson trichrome stain for fibrous tissue were used for histological evaluation. Liver needle biopsies were available from 3 patients and in addition 1 liver biopsy was available from liver explant in a patient who underwent orthotopic liver transplantation (Table 1, No. 1).

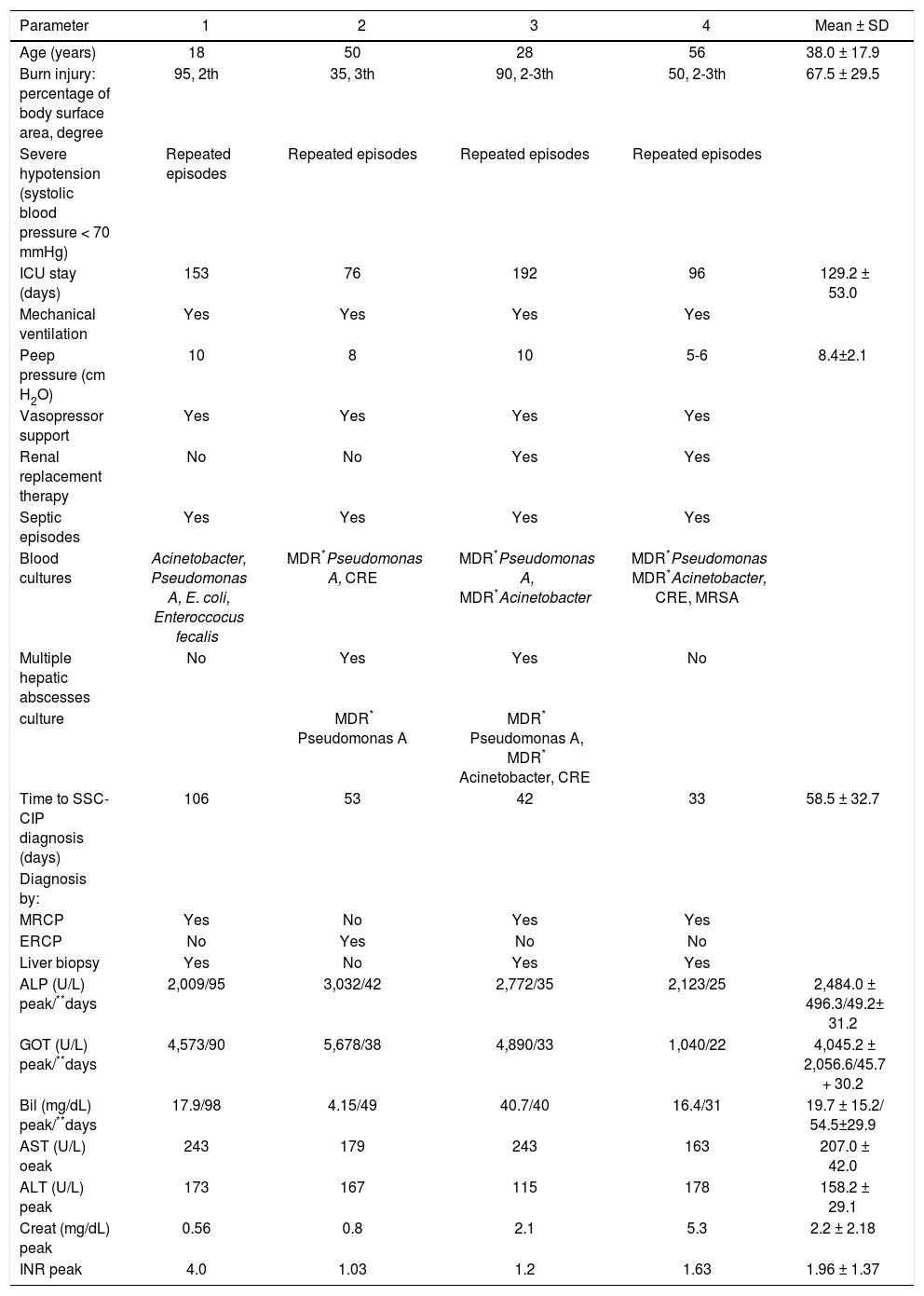

Baseline characteristics at diagnosis of SSC-CIP following burn injury.

| Parameter | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18 | 50 | 28 | 56 | 38.0 ± 17.9 |

| Burn injury: percentage of body surface area, degree | 95, 2th | 35, 3th | 90, 2-3th | 50, 2-3th | 67.5 ± 29.5 |

| Severe hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 70 mmHg) | Repeated episodes | Repeated episodes | Repeated episodes | Repeated episodes | |

| ICU stay (days) | 153 | 76 | 192 | 96 | 129.2 ± 53.0 |

| Mechanical ventilation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Peep pressure (cm H2O) | 10 | 8 | 10 | 5-6 | 8.4±2.1 |

| Vasopressor support | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Renal replacement therapy | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Septic episodes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Blood cultures | Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas A, E. coli, Enteroccocus fecalis | MDR*Pseudomonas A, CRE | MDR*Pseudomonas A, MDR*Acinetobacter | MDR*Pseudomonas MDR*Acinetobacter, CRE, MRSA | |

| Multiple hepatic abscesses | No | Yes | Yes | No | |

| culture | MDR* Pseudomonas A | MDR* Pseudomonas A, MDR* Acinetobacter, CRE | |||

| Time to SSC-CIP diagnosis (days) | 106 | 53 | 42 | 33 | 58.5 ± 32.7 |

| Diagnosis by: | |||||

| MRCP | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| ERCP | No | Yes | No | No | |

| Liver biopsy | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| ALP (U/L) peak/**days | 2,009/95 | 3,032/42 | 2,772/35 | 2,123/25 | 2,484.0 ± 496.3/49.2± 31.2 |

| GOT (U/L) peak/**days | 4,573/90 | 5,678/38 | 4,890/33 | 1,040/22 | 4,045.2 ± 2,056.6/45.7 + 30.2 |

| Bil (mg/dL) peak/**days | 17.9/98 | 4.15/49 | 40.7/40 | 16.4/31 | 19.7 ± 15.2/ 54.5±29.9 |

| AST (U/L) oeak | 243 | 179 | 243 | 163 | 207.0 ± 42.0 |

| ALT (U/L) peak | 173 | 167 | 115 | 178 | 158.2 ± 29.1 |

| Creat (mg/dL) peak | 0.56 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 5.3 | 2.2 ± 2.18 |

| INR peak | 4.0 | 1.03 | 1.2 | 1.63 | 1.96 ± 1.37 |

After diagnosis of SC-CIP, all patients received ursodesoxycholic acid (UDCA) at a dose of at least 15 mg/kg per day to improve bile flow. According to the results of the microbiological sensitivity tests of the blood and drained hepatic abscesses cultures, antibiotic treatment was adapted including Rifampin/Imipenem based combination for MDR pathogens. Vasopressor support (epinephrine or norepinephrine > 0.1 µg/kg/min) was administered when hemodynamic instability occurred.

ERCP and sphincterotomy with extraction of biliary casts or stent insertion was performed when necessary.

ResultsPatient characteristics at diagnosis of SSC-CIP (Table 1)The mean age of the patients was 38.0 ± 17.9 yr (range, 18-56 yr); all male. Mean burn percentage of body surface area injury was 67.5 ± 29.5 (range, 35-95%). Mean ICU stay was 129.2 ± 53.0 days (range, 76-192 days). All patients required mechanical ventilation with a mean PEEP value of 8.4 ± 2.1 cm H2O. All of them experienced hypotensive episodes (systolic blood pressure < 70 mmHg) and required vasopressor support. Time to diagnosis of SSC-CIP was 58.5 ± 32.7 days. Renal replacement therapy was required in 2 patients.

A patients experienced septic episodes. Blood cultures in four patients and cultures from drained liver abscesses in 2 additional patients, grew hospital acquired multiple resistant bacteria (Table 1), mainly Pseudomonas A and Acinetobacter.

The mean peak serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level was 2,484.0 ± 496.3 U/l (range, 2,009-3,032 U/l). Peak was reached in a mean of 49.2 ± 31.2 days. The mean peak serum gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) level was 4,045.2 ± 2,056.6 U/L (range, 1,040-5,678 U/l). Peak was reached in a mean of 45.7 ± 30.2 days. Mean bilirubin level 19.7 ± 15.2 mg/dL (range, 4.15-40.7 mg/dL). Peak was reached in a mean of 54.5 ± 29.9 days.

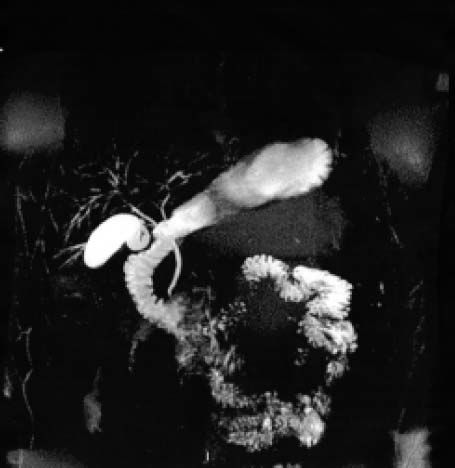

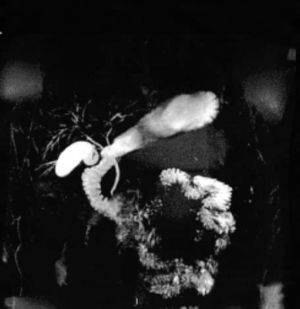

Imaging features of secondary sclerosing cholangitisMRCP was performed in 3 patients. MRCP disclosed irregular intrahepatic bile ducts with multiple strictures and dilatations (comparable to lesions detected in primary sclerosing cholangitis) (Figures 1 and 2). ERCP performed in 1 patient demonstrated multifocal strictures and dilatations of the intrahepatic bile ducts (comparable to lesions in primary sclerosing cholangitis). After cannulation of the common bile duct endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed and a stent was inserted. The common bile duct and the cystic duct were normal in all patients.

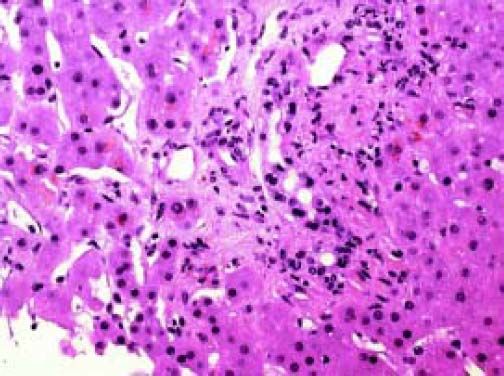

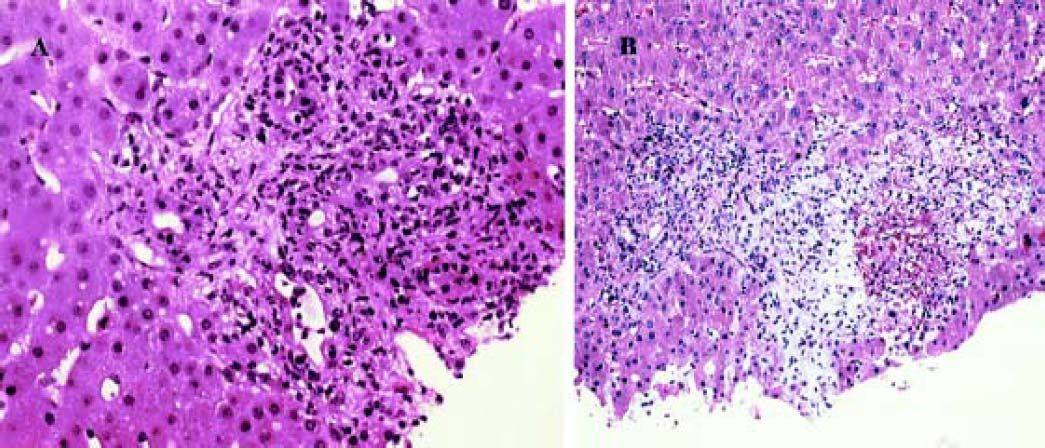

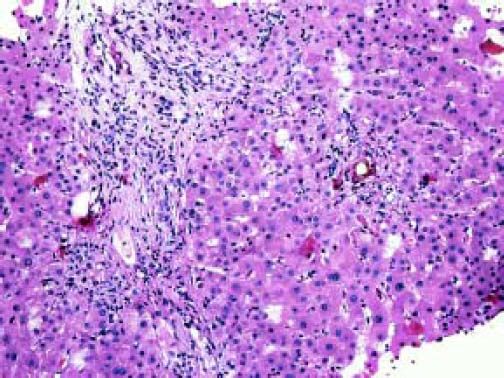

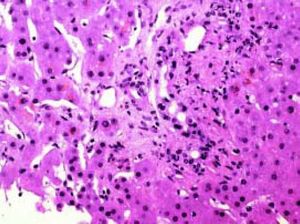

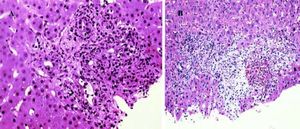

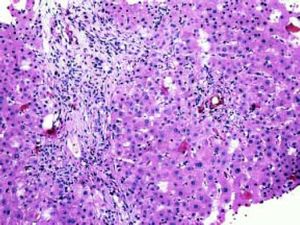

Histological analysis was available from 4 biopsied performed in 3 patients (in patient No.1, sequential biopsies were performed). (Table 1, Figures 3-5). In the first stage (biopsy performed within 3 months of diagnosis, patient No. 1) (Figure 3) portal edema with neutrophils infiltrate and bile ducts damage was noted with uneven spacing and hyperchromasia of nuclei. In the second stage (biopsy performed within 8 months) portal edema and early fibrosis was demonstrated associated with bile ducts damage, cholestasis, cholangiolar proliferation accompanied by neutrophils infiltrates (Figure 4A, patient No. 3) and bile infarct (Figure 4B). In the third stage (biopsy performed within 12 months, patient No. 1, explanted liver) incomplete cirrhosis with diffused septal formation (Figure 5) has developed, cholestasis, cholangiolar proliferation and bile plugs, ulcerated and degenerative changes in epithelial bile duct and sludge were noted.

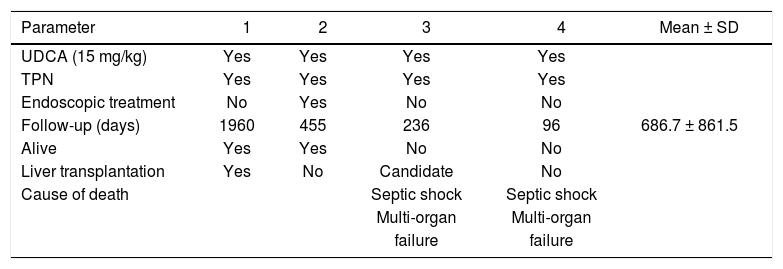

Outcome (Table 2)

Treatment and outcome.

| Parameter | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UDCA (15 mg/kg) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| TPN | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Endoscopic treatment | No | Yes | No | No | |

| Follow-up (days) | 1960 | 455 | 236 | 96 | 686.7 ± 861.5 |

| Alive | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| Liver transplantation | Yes | No | Candidate | No | |

| Cause of death | Septic shock | Septic shock | |||

| Multi-organ | Multi-organ | ||||

| failure | failure |

TPN: total parenteral nutrition.

Two patients died due to multi-organ failure and septic shock, one of them was placed on the waiting list for liver transplantation however a transplant was not performed due to the advanced stage and the debilitating state of the patient. One patient underwent liver transplantation (within 12 months of diagnosis) due to recurrent episodes of ascending cholangitis, severe cholestasis and progression of the liver disease (cirrhosis). One patient with less extended sclerosing of the bile ducts and without significant stenosis is not progressing.

DiscussionWe have presented for the first time, a case series of rapidly progressive SSC-CIP requiring aggressive intensive care treatment following major burn injury. The serum levels of total bilirubin, ALP, and GGT were at least 10 times higher than the normal levels. The diagnosis of SSC-CIP was based on MRCP, and/or ERCP and liver histology. Prognosis was poor as 50% died, additional patient underwent liver transplantation and in one patient there was no progression. Only 8 similar cases that were related to major burns were previously reported.5,8,10,11 The mechanisms leading to SSC-CIP are widely unknown; however, it is likely mediated through ischemic injury to the bile ducts.1 The ischemic injury to the intrahepatic biliary tree is followed by bacterial colonization leading to destructive biliary changes which is the leading event in the development of this severe form of SSC-CIP.3 We have detected septic episodes in all patients despite the use of multiple antibiotics. Hospital acquired MDR bacteria were detected as the major pathogen in most of our patients.

Biliary ischemia is considered as a direct cause of secondary sclerosing cholangitis. The risk factors for ischemic biliary insult in patients with SSC-CIP are:

- •

Splanchnic perfusion may be significantly altered when cardiocirculatory function deteriorates during mechanical ventilation. PEEP > 10 cm H2O has been shown to decrease splanchnic perfusion by reducing cardiac output and venous return, thereby increasing the risk of visceral ischemia.7,12 The appropriate level of PEEP should be further investigated.

- •

Hemodynamic instability. All our patients experienced hemodynamic instability, and systemic arterial hypotension (< 70 mmHg), requiring vasopressor support. However, the role of hemodynamic instability and of vasopressor in the pathogenesis of SSC-CIP is controversial.7,13,14

In most cases of SSC-CIP, diagnosis using ERCP has demonstrated a PSC like pattern of beading primarily of the intrahepatic bile ducts.5,6,11 Early ERCP findings included the presence of filling defects of intrahepatic bile ducts secondary to the formation of extensive biliary casts.1 Later on (within weeks) ERCP revealed multiple intrahepatic bile ducts strictures. The progression of SSC-CIP was more aggressive than other forms of SSC leading to liver cirrhosis within several months.1 In a recently published study11 in which 29 patients with SSCCIP were included, all of them underwent ERCP and 20 endoscopic treatments were performed including sphincterotomy. These endoscopic therapies resulted in biochemical improvements however, the progressive destruction of the biliary tree could not be prevented by endoscopic therapy and the outcome of patients with and of those without endoscopic therapy was not significantly different.5,6,11 We have diagnosed SSC-CIP in 3 of our patients using MRCP. Since the destruction of the biliary tree could not be prevented by ERCP, we suggest using MRCP, a non-invasive procedure as the primary imaging modality for the diagnosis of SSC-CIP instead of ERCP that usually should be avoided in critically ill patients.

Liver histology data in patients with SSC-CIP is very limited.3,10 As Ruemmele, et al.1 stressed in their review, the only detailed liver biopsies descriptions of SSC-CIP have been provided by Gelbmann, et al.3 and Esposito, et al.10 In the early stage (first 1-3 months) findings are variable ranging from nonspecific changes to the presence of features that are suggestive of biliary duct obstruction.1 Within 4-12 months, progressive loss of intrahepatic bile ducts, marked bile ducts proliferation, portal, periportal and periductular fibrosis, and hepatocanalicular cholestasis occurred. Within 14-17 months incomplete or complete liver cirrhosis developed.1 We have performed in our study 4 liver biopsies in 3 of our patients. We were able to analyze sequential liver biopsies in the patient who underwent a liver transplantation (No.1). Biopsy performed within 3 months of diagnosis, demonstrated portal edema with neutrophils infiltrate and bile ducts damage while the explanted liver from the same patient (12 months later) has progressed to incomplete cirrhosis. A shorter time frame for the development of cirrhosis when comparing the limited data previously published.1 Biopsies performed in the additional 2 patients (not sequential) has also demonstrated the different stages that developed within a short period of time (months) and a progression from portal edema to early fibrosis, bile infarct to and incomplete cirrhosis.

UDCA is used to treat various chronic cholestatic diseases. However, no randomized controlled trial has evaluated the therapeutic value of UDCA in patients with SSC-CIP.

Poor prognostic factors are the degree of hepatic fibrosis detected in the liver biopsy and involvement of other organs as the kidney. Multi-organ failure and sepsis were the cause of death unless liver transplantation was performed. In a recently published study by Lin, et a/.7 the prognosis of SSC-CIP was investigated in 88 patients. Poor outcomes were observed in 54 (62.1%) patients, including death in 34 patients and liver transplantation in others.

In conclusion, SSC-CIP following major burn injury is a rapidly progressive disease with a poor outcome. It is associated with sepsis and hospital acquired multiple resistant bacteria. Histological analysis of liver biopsy samples taken at different time points revealed that liver cirrhosis developed within 12 months. In many cases SSC-CIP is probably overlooked and the true prevalence of this disease is underestimated. The pathogenic mechanisms leading to this condition warrant further elucidation. Awareness of this grave complication is needed for prompt diagnosis and considerations of a liver transplantation.

Abbreviations- •

ALP: alkaline phosphatase.

- •

ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

- •

GGT: gamma glutamyl transpeptidase.

- •

H&E: hematoxylin-eosin.

- •

ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

- •

MRCP: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.

- •

PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure.

- •

SSC: secondary sclerosing cholangitis.

- •

SSC-CIP: secondary sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill patients.

- •

TPN: total parenteral nutrition.

- •

UDCA: ursodesoxycholic acid.

The study was not supported by grants.