Alcohol-associated hepatitis is a clinical syndrome characterized by recent onset jaundice and/or the other signs of liver decompensation in people with heavy alcohol use [1]. Severe alcohol-associated hepatitis (SAH), which is defined as Maddrey's discriminant function (mDF)≥32, is a dismal condition with a 28-day mortality of 34 % in untreated patients [2]. In SAH patients, corticosteroids and pentoxifylline treatment were used. A meta-analyses showed that corticosteroid treatment in SAH improved 1-month mortality [3,4]. However, in the Steroid or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis (STOPAH) study, corticosteroid was associated with 28-day mortality reduction but not with 3-month and 6-month mortality in patients with SAH [5]. In addition, the survival benefit of pentoxifylline is uncertain [3,5], Therefore, new treatment strategies for SAH are needed.

In SAH patients, gut dysbiosis plays an important role. Alcohol consumption changes the gut microbiome and disrupts the intestinal epithelial barrier [6]. Gut dysbiosis in SAH leads to increased gut permeability and translocation of viable bacteria or their products, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or peptidoglycan [7,8]. These microbial products of portal or systemic circulation increase alcohol-induced liver injury and inflammation [6,8]. Therefore, gut microbiome modulation is considered a new target for SAH treatment.

LPS is a component of gram-negative bacteria that triggers an inflammatory response via toll-like receptor (TLR)-4. LPS-binding protein (LBP) binds to lipid A of bacterial LPS, enhancing host immune response to LPS. LPS and LBP can be used as bacterial translocation markers, and an increase of LPS and LBP is associated with poor prognosis of liver disease [9]. In practice, SAH patients with high serum LPS levels showed poor survival with frequent multiorgan failure and a lower corticosteroid response rate [10].

Rifaximin is a poorly absorbable broad-spectrum antibiotic against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and has a low risk of bacterial resistance [11]. Rifaximin is used to treat hepatic encephalopathy or to treat recurrent or refractory Clostridium infections. In patients with hepatic encephalopathy, it is thought that rifaximin modulates the intestinal microbiome and reduces gut-derived neurotoxins, such as ammonia [12]. In patients with alcohol-associated liver cirrhosis, rifaximin improved systemic hemodynamics and renal function by reducing serum endotoxin levels [13]. In addition, rifaximin administration reduced the risk of developing complications related to portal hypertension and improved survival [14–16].

Therefore, we aimed to assess the effectiveness of adding rifaximin to corticosteroids or pentoxifylline in SAH patients in this prospective study.

2Materials and methods2.1Study patientsThis multicenter, randomized, open-label pilot trial was performed on patients hospitalized between September 2015 and January 2019 in 6 Korean hospitals. The eligibility criteria were an age of 18–75 years and chronic heavy drinking (>40 g/day for men and >30 g/day for women) [17] with severe alcohol-associated hepatitis. Chronic heavy drinking was defined as active drinking for at least 3 months and until at least 3 months before presentation, and severe alcohol-associated hepatitis was defined as follows: 1) mDF ≥ 32, 2) recent onset jaundice within 3 months (bilirubin ≥ 3 mg/dL), 3) aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio ≥ 1.5, and 4) one or more of the following clinical findings: hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, hepatomegaly, and leukocytosis with predominantly neutrophilic differentiation. The exclusion criteria included 1) the existence of other etiologies of chronic liver disease, such as chronic hepatitis B, hepatitis C or autoimmune hepatitis, 2) acute viral hepatitis (hepatitis A or E), 3) drug-induced hepatotoxicity, 4) antibiotic or probiotic use within 8 weeks, 5) hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) of stage 2 or more, 6) malignancy other than HCC, 7) pregnancy, 8) type 1 hepatorenal syndrome, 9) hepatic encephalopathy of West Haven grade 3 or 4, 10) severe infection, and 11) gastrointestinal bleeding with transfusion of more than 3 units of blood, 12) patients lost to follow-up within 28 days.

2.2Study designThe patients with SAH were scheduled to be treated with 40 mg of prednisolone per day or 400 mg of pentoxifylline taken three times daily in the steroid-ineligible patients for 4 weeks, irrespective of the treatment response assessed using the Lille model. The steroid-ineligibility criteria were uncontrolled bacterial infection, concomitant pancreatitis, acute kidney injury, and uncontrolled upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The patients meeting the criteria were randomized into two groups at a 1:1 ratio, with one group receiving a dosage of 400 mg of rifaximin three times daily and the control group receiving no additive treatment (without placebo). To ensure balanced allocation between rifaximin group and control group, block randomization with a block size of four was employed. Each block contained 2 participants assigned to the rifaximin group and 2 to the control group. A computer-generated algorithm created random permutations within each block, using all possible permutations to achieve balance and maintain equal group sizes. Randomization was stratified based on SAH treatment (corticosteroid and pentoxifylline) and participating hospital. Each participating hospital's principal investigator was responsible for assigning patients according to the randomization table.

2.3Data collectionWe collected data on patient demographics, alcohol consumption, laboratory measurement, and comorbid liver-related complications. Clinical data within 24 hours prior to 1st day and 28 days after prednisolone or pentoxifylline treatment were collected. Comorbid liver-related complications included ascites, bacterial infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatorenal syndrome, and hepatic encephalopathy. Gastrointestinal bleeding was divided into variceal bleeding and gastrointestinal bleeding other than variceal bleeding. The use of antibiotics was permitted for patients in whom a bacterial infection was diagnosed or suspected, and the use of antibiotics was investigated. The selection of antibiotics, as well as the dosage and duration of their administration was determined at the discretion of the clinician. Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score [18] was calculated at the 1st and 28th day of prednisolone or pentoxifylline treatment. The formula of MELD score was as follows; MELD score = (0.957 × ln(Serum Cr) + 0.378 × ln(Serum Bilirubin) + 1.120 × ln(INR) + 0.643 ) × 10 (if hemodialysis, value for Creatinine is automatically set to 4.0). For patients without events within 7 days post-enrollment, the Lille model was calculated irrespective of corticosteroid or pentoxifylline treatment.

2.4OutcomeThe primary outcome was survival without liver transplantation at 6 months. Patients who received transplantation were regarded as dead. The secondary outcome was transplantation-free survival at 90 days.

2.5Determination of serum LPS and LBP levelsSerum samples were obtained from the peripheral blood on the first day and 28th day of prednisolone or pentoxifylline treatment. Serum levels of LPS and LBP were determined using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits following the manufacturer's instructions (Cusabio Biotech Co., Wuhan, China).

2.6Sample sizeThe 6-month survival rate for SAH patients receiving corticosteroid therapy was 65 % [19]. Assuming 20 % reduction in the 6-month mortality rate with rifaximin compared to corticosteroid treatment alone, with a significance level (α error) of 5 % and power of 80 %, 77 patients were required in each group. Assuming for a 10 % dropout rate, we adjusted the sample size to 85 patients per group, total 170 patients. However, due to difficulties in patient recruitment, we were unable to achieve the target sample size and subsequently had to terminate the study prematurely. Therefore, we conducted a pilot analysis with the available data to assess preliminary outcomes.

2.7Statistical analysisContinuous variables were represented by means ± standard deviations (SDs) or medians (ranges), while categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. Comparisons between the two groups were made using Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. The period from the initial day of SAH treatment ± rifaximin until death or liver transplantation. For those patients who did not encounter the events of interest, their data were censored on the date of their last follow-up visit. Transplantation-free survival time was assessed with the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences in survival were evaluated using the Tarone-Ware test. Cox proportional hazards model, using the backward stepwise likelihood ratio method, was applied to determine the independent predictors of 3-month and 6-month transplant-free survival with a two-sided test and a significance threshold of 0.05. Multivariate analysis was performed with variables with P<0.1 in univariate analysis. When the MELD score was included in the multivariate analysis, the components of MELD score (bilirubin, creatinine, and INR) were excluded to avoid multicollinearity. Statistical significance was defined as a P value under 0.05. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS, Inc. IBM Company, Chicago, IL, USA).

2.8Ethical statementAll participants provided written informed consent. This study received approval from the institutional review board at each participating hospital and adhered to the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study has been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02485106). Each co-authors had access to the study data, and all reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

3Results3.1PatientsDuring the study period, 58 patients were screened, and after the application of the eligibility criteria, 55 patients were randomized to the two groups: 30 to the control group and 25 to the rifaximin treatment group. One patient in the control group (withdrawal of consent) and 4 patients in the rifaximin treatment group (3 patients withdrew consent, and one patient was followed for less than 28 days) were excluded, and 29 patients in the control group and 21 patients in the control treatment group were analyzed in this study (Fig. 1).

The baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients are reported in Table 1. The mean age was 48.4 ± 9.2 years, and 35 patients (70.0 %) were male. Thirty-six patients (72.0 %) were treated with corticosteroids, and concomitant antibiotics were used in 33 patients (66.0 %). There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the control and rifaximin groups. However, the rifaximin treatment group had significantly higher serum procalcitonin levels than the control group (1.07 vs. 0.46 ng/mL, P = 0.044).

Baseline characteristics.

Abbreviation: GI, Gastrointestinal; mDF, modified discriminant function; MELD, Model for End Stage Liver Disease; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; INR, international normalized ratio.

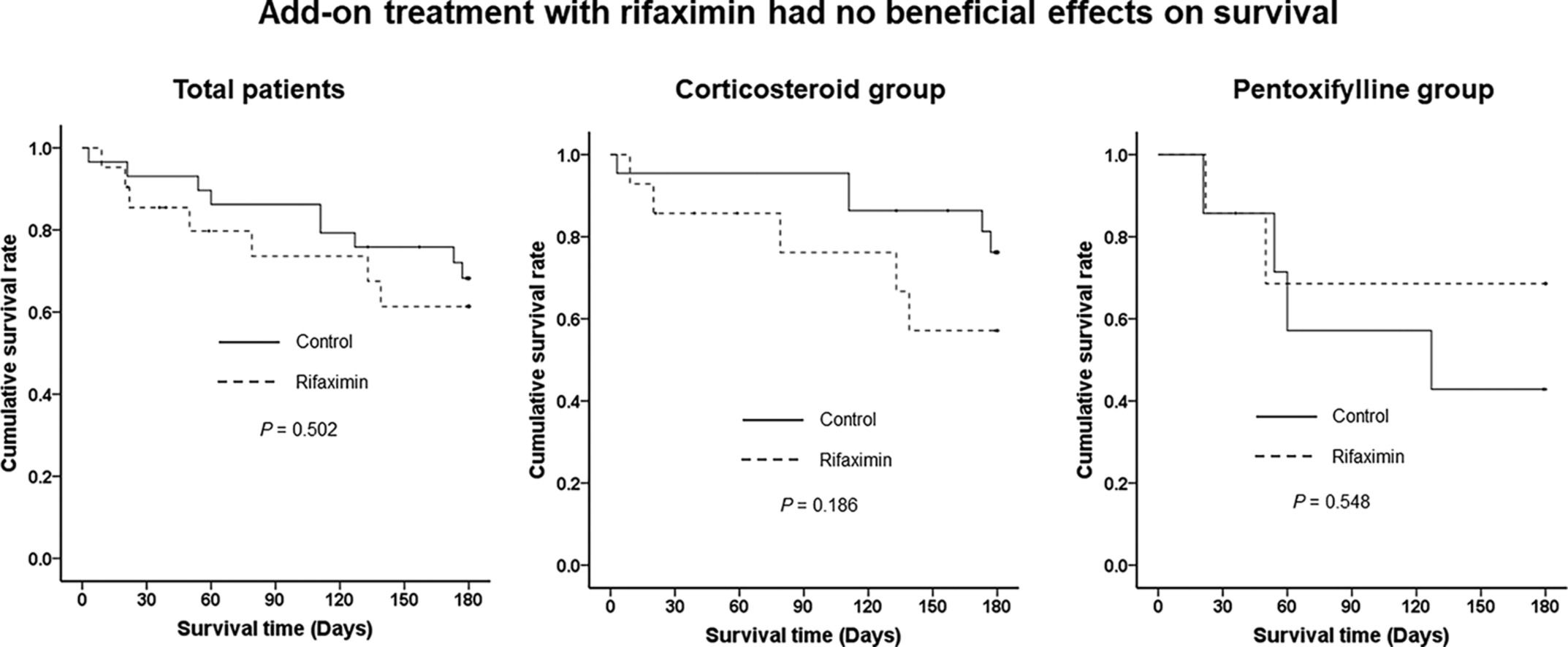

There were no significant differences in 90-day and 180-day LT-free survival between the control and rifaximin groups (86.2 % vs. 73.6 %, P = 0.289 at 90 days and 68.3 % vs. 61.3 %, P = 0.502 at 180 days, respectively) (Fig 2). At 4 weeks after enrollment, the MELD score was significantly decreased in both groups compared to baseline (−5.8 ± 4.1, P < 0.001 in the control group and −6.6 ± 4.9, P < 0.001 in the rifaximin group), but there was no significant difference in the improvement of MELD scores over 4 weeks between the two groups (Fig. 3A). The serum LPS levels were not decreased in either the control or rifaximin groups (−0.4 ± 136.9, P = 0.990 in the control group and −33.7 ± 81.8, P = 0.252 in the rifaximin group), and there was no significant difference between the two groups in the LPS decrease (P = 0.515) (Fig. 3B). The serum LBP levels were significantly decreased in the rifaximin group (−12.0 ± 14.3, P = 0.026). However, there was no significant change in the serum LBP levels in the control group (−1.4 ± 34.4, P = 0.872), and there was no significant difference in the decrease in serum LBP levels between the two groups (P = 0.366) (Fig. 3C).

When we stratified by SAH treatment, there were no significant differences in 90-day and 180-day LT-free survival between the control and rifaximin treatment groups in either the corticosteroid (95.5 % vs. 76.2 %, P = 0.122 at 90 days and 76.2 % vs. 57.1 %, P = 0.186 at 180 days) or pentoxifylline treatment groups (57.1 % vs. 68.6 %, P = 0.791 at 90 days and 42.9 % vs. 68.6 %, P = 0.548 at 180 days) (Fig. 4).

Kaplan-Meier curves of 3-month and 6-month LT-free survival stratified by treatment of severe alcohol-associated hepatitis. (A) 3-month LT-free survival in the corticosteroid group. (B) 3-month LT-free survival in the pentoxifylline group. (C) 6-month LT-free survival in the corticosteroid group. (D) 6-month LT-free survival in the pentoxifylline group. Abbreviation: LT, liver transplantation.

In this study, 33 patients (66.0%) used antibiotics concomitantly. We analyzed the effect of rifaximin by stratifying patients based on the use of concomitant antibiotics. There were no significant differences in 180-day LT-free survival between the rifaximin and control groups in both the concomitant antibiotics and no antibiotics arms (P = 0.366 in antibiotics group and P = 0.899 in no antibiotics group) (Supplementary Fig 1).

3.5Factors associated with 3-month and 6-month LT-free survivalWe used the Cox proportional hazards model to identify risk factors associated with 3-month and 6-month LT-free survival in all patients without applying stratification. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was employed to adjust for confounding factors potentially introduced by the open-label design and the small sample size, which did not reach the intended target. For 3-month LT-free survival, baseline MELD score, white blood cell count, serum bilirubin, creatinine, international normalized ratio (INR), and C-reactive protein level were significant factors, and SAH treatment was marginally significant factor (P values between 0.05 and 0.10). We performed multivariate analysis with these factors except for the components of the MELD scores because the MELD score includes serum bilirubin and creatinine levels and INR. In the multivariate analysis, the MELD score was the only significant factor associated with 3-month LT-free survival in the patients with SAH (hazard ratio (HR) 1.241, P < 0.001) (Table 2). For 6-month LT-free survival, baseline MELD score, serum creatinine and INR were significant factors, and white blood cell count was marginally significant factor in the univariate analysis. In multivariate analysis, MELD score was only significant factor for 6-month LT-free survival. Rifaximin treatment was not a significant factor for 3-month and 6-month LT-free survival (HR 2.025, P = 0.294 for 3-month and HR 1.367, P = 0.537 for 6-month).

Factors associated with 3-month and 6-month liver transplantation-free survival.

Abbreviation: SAH, severe alcohol-associated hepatitis; MELD, Model for End Stage Liver Disease; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; INR, international normalized ratio; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; LBP, lipopolysaccharide binding protein

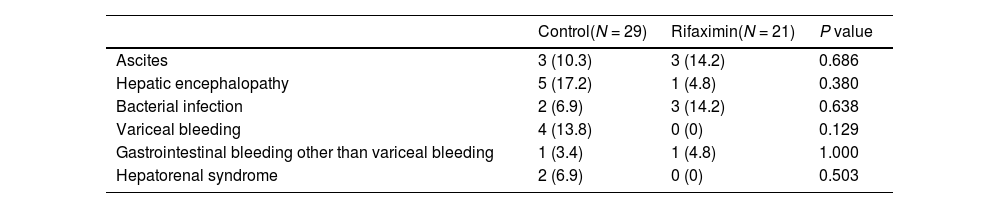

We investigated the development of new liver-related complication for 4 weeks. In the control group, hepatic encephalopathy was the most frequent complication (17.2 %), followed by variceal bleeding (13.8 %) and ascites (10.3 %) for 4 weeks. In the rifaximin group, bacterial infection and ascites were the most frequent complications (14.2 % and 14.2 %), followed by hepatic encephalopathy (4.8 %) and gastrointestinal bleeding other than variceal bleeding (4.8 %). There was no significant difference in the occurrence of liver-related complications between the two groups at 4 weeks (Table 3). One patient in the rifaximin group discontinued on day 11 due to paralytic ileus.

Liver-related complications.

The results of this pilot study indicate that rifaximin treatment does not improve the prognosis in patients with SAH. Rifaximin treatment was not effective in either the standard treatment group, corticosteroid group, or pentoxifylline group. In addition, rifaximin treatment did not affect the recovery of liver function or gut microbial translocation and did not reduce the occurrence of liver-related complications.

Rifaximin, a poorly absorbable antibiotic, is used for preventing recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, and its mechanism is presumed to reduce ammonia production by modulating the gut microbiome [20,21], In addition, some studies reported that rifaximin treatment improved portal hypertension and prognosis in patients with decompensated cirrhosis [14,22], However, previous studies on rifaximin treatment in SAH patients showed conflicting results. Jiménez et al. reported that the addition of rifaximin to standard treatment was associated with significantly lower bacterial infections and liver-related complications and a trend toward lower mortality without significant differences [23]. On the other hand, Kimer et al. showed that mortality and hepatic function were not affected by the addition of rifaximin and that there were no differences in inflammation and metabolism markers [24]. Our study also showed that add-on treatment with rifaximin in SAH patients had no beneficial effects on survival or the prevention of complications. However, studies on rifaximin in SAH, including our study, all had a small number of patients. Therefore, it is necessary to verify the effectiveness of rifaximin through a well-designed RCT that includes more patients in the future.

Enteric dysbiosis is thought to be a central component of alcohol-associated hepatitis [25,26]. Transplantation of fecal microbiota of SAH patients increased the susceptibility to alcohol-associated liver disease [27], and healthy donor fecal microbiota transplantation improved prognosis in SAH patients [28]. Therefore, modulation of the intestinal microbiome is emerging as a promising therapeutic option. Rifaximin is also known to modify the gut microbiome by changes in the bile acid composition or microbiome function rather than the gut microbiome composition in patients with chronic liver disease [20,29,30]. Bajaj et al. [30] and Yu et al. [31]. showed a significant change in bacterial metabolic function without a significant change in the gut microbiome after rifaximin treatment in cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Pose et al. [32] also showed that rifaximin and simvastatin treatment was associated with reduced change of plasma metabolite in decompensated cirrhosis patients. However, in the study that analyzed the fecal microbiome of SAH patients included in this study, there were no significant changes in not only in the composition of the gut microbiome but also in the metabolic pathway after rifaximin treatment [33]. Kimer et al. also reported that rifaximin treatment did not change inflammatory and metabolic markers in SAH patients [24]. Unlike cirrhosis, failure of rifaximin to change microbiome function would not have improved the prognosis in SAH patients. The difference in the outcome of rifaximin treatment in cirrhosis and SAH may have arisen from the gut microbial composition and function between the two diseases [34]. Therefore, research is needed to identify and modulate the SAH-specific gut microbiome and its functions that can improve the prognosis of alcohol-associated hepatitis.

Enhanced intestinal permeability also contributes to alcohol-associated hepatitis. Increased gut permeability leads to an increased load of gut-derived bacterial products such as LPS in the portal circulation and liver, and increased endotoxin leads to hepatic inflammation and fibrosis [26,35,36]. Increased serum LPS also plays a role in the systemic inflammatory response and the development of complications of cirrhosis [37,38]. Michelena et al. showed that serum LPS levels were correlated with the severity of AH and that increased serum LPS predicted the development of multiorgan failure and corticosteroid response [10]. Some studies reported that rifaximin treatment lowered serum endotoxin levels in alcohol-associated cirrhosis [13,30]. However, rifaximin treatment did not significantly lower serum LPS and LBP levels in patients with SAH compared with the nontreated group in this study. This result suggests that rifaximin treatment is insufficient to improve gut permeability and reduce bacterial translocation in patients with SAH. The failure to reduce gut permeability after rifaximin treatment may also be associated with the failure to modulate the gut microbiome.

This study has several limitations. First, this study included too small a number of patients. Further studies including a sufficiently larger number of patients are warranted to prove the effectiveness of adding rifaximin in patients with SAH. Second, although this study is designed as an RCT, the possibility that the bias of the researcher or patients is involved should be considered because this is an open-label study without a placebo group. In fact, the rifaximin group had a higher MELD score than the control group, suggesting that rifaximin group included sicker patients (Table 1). Therefore, a blinded RCT with a placebo would be needed to reduce bias in the future. Third, pentoxifylline was included as the standard treatment for SAH. After the STOPAH study showed that pentoxifylline was ineffective in SAH [5], only corticosteroids were used as standard treatment for SAH. However, at the beginning of this study, pentoxifylline was able to be used as a standard treatment, and pentoxifylline was not used in this study, since its use was not recommended by both the EASL and AASLD guidelines. Additionally, because this study used block randomization stratified by SAH treatment and adding rifaximin was ineffective in both pentoxifylline and corticosteroid groups, pentoxifylline treatment as standard treatment would not have affected the results of adding rifaximin in SAH. Fourth, a substantial number of patients used concomitant antibiotics. In this study, concomitant antibiotics did not affect the effectiveness of rifaximin. However, research is also needed on the differences in the type and severity of infections and the type of antibiotics used in the future.

Although the study did not achieve the target enrollment, which limits its statistical power, the strength of this study lies in being conducted as a RCT. This study is valuable as a pilot study to determine the appropriate study design for future research on the utility of rifaximin in patients with SAH. Furthermore, the absence of a therapeutic benefit from rifaximin in SAH, in contrast to its efficacy in patients with alcohol-associated cirrhosis, suggests distinct differences in the pathophysiology of SAH and alcohol-associated cirrhosis. This indicates that future studies on SAH should be designed differently from those on alcohol-associated cirrhosis.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, adding rifaximin to standard treatment in patients with SAH did not improve short-term LT-free survival and did not prevent the development of liver-related complications. The only significant factor for short-term LT-free survival was the MELD score at baseline. However, given that this is a pilot study, further studies that are well-designed and include a larger number of patients are warranted.

Author contributionConceptualization: Do Seon Song, Young Kul Jung; Data curation: Do Seon Song, Young Kul Jung, Hyung Joon Yim, Hee Yeon Kim, Chang Wook Kim, Soon Sun Kim, Jae Youn Cheong, Hae Lim Lee, Sung Won Lee, Jeong-Ju Yoo, Sang Gyune Kim, Young Seok Kim; Formal analysis: Do Seon Song, Young Kul Jung, Hee Yeon Kim, Soon Sun Kim, Sung Won Lee, Jeong-Ju Yoo; Writing-original draft: Do Seon Song; Project administration: Hyung Joon Yim, Chang Wook Kim, Jae Youn Cheong, Sang Gyune Kim, Young Seok Kim; Supervision: Jin Mo Yang, Young Seok Kim. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Dr. Young Kul Jung is an Editorial Board member of JGH and a co-author of this article. To minimize bias, they were excluded from all editorial decision-making related to the acceptance of this article for publication.