Liver-related events (LRE), including liver cirrhosis and its complications, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver-related deaths, are a major global public health concern. Annually, liver diseases account for approximately 2 million deaths worldwide, constituting 3.5 % of total mortality [1]. The burden of chronic liver diseases, including cirrhosis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), and viral hepatitis, continues to rise, emphasizing the urgent need for effective prevention and treatment strategies [2]. While medical advancements have been made, there is currently no definitive cure for many liver-related diseases, making LRE a pressing issue worldwide.

Research has identified various risk factors for LRE, including alcohol consumption, diet, lifestyle habits, and sleep patterns [3–6]. Recent time-based studies have shown the important part that sleep can play in the development and the progression of the liver diseases. Impaired sleep, which includes shorter or longer sleep patterns, daytime sleep, snoring, and insomnia is closely associated with the risk of liver mortality [7–10]. On the other hand, having healthy sleep habits could provide a protective factor to LRE and other chronic conditions [11,12]. For example, a study by Hsieh et al. showed that individuals who slept for more than 7 h each night had a reduced risk of developing fatty liver disease [13]. Similarly, Kim et al. suggested that short sleep durations and poor sleep quality increase the risk of MASLD [14]. The adverse effect of the poor sleep patterns, such as short sleep duration and insomnia on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is established. These disturbances cause an increased oxidative stress, systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction all of which increase the risk of liver-related events [15]. Moreover, the use of sleep treatment has shown some promise towards the alleviation of all-cause deaths related to liver cancer [16]. Most of the literature is prospective studies that investigate the general relationship between sleep pattern and LRE regardless of the cause of the disease given its limited prevalence in this search of knowledge and despite these findings there are few studies about the overall relationship between sleep pattern and LRE in light of the limited prevalence of the disease in the quest of knowledge.

One promising approach to studying sleep patterns is the concept of a ‘Healthy Sleep Pattern’ (HSP), a composite score developed by Fan et al. [17]. The score is a combination of different types of sleep-related scales, such as sleep duration, insomnia, daytime sleepiness, chronotype, and snoring. Prior findings indicated that a greater HSP score is related to better health effects, including a lowered risk of cardiovascular diseases and metabolism disorders and an enhanced cognitive ability [18–23]. Furthermore, research has indicated that maintaining a healthy sleep pattern may lower the risk of MASLD [17,25]. Individual sleep behaviors were investigated in isolation, but the composite approach also attempts to consider cumulative effects of various sleep factors and so may provide a more complete presentation of how sleep contributes to health. Nevertheless, it is important, at the same time, to take into account the strengths and weaknesses of such an aggregation. On the one hand, it will give a global picture of the health of sleep because it will combine multiple facets. Conversely, the validity of the scoring system has to be ascertained and a judgment on whether the various factors are attached usually by aggregating the responses to them serves to mask the specificity aspect of single sleep behaviors. Therefore, although the composite method is quite informative, one needs to thoroughly evaluate how effective it is in allowing the complexity of sleeping behaviors to remain without simplifying and considering individual effects.

This highlights a gap in the literature: the relationship between a comprehensive healthy sleep pattern and LRE, particularly liver cirrhosis and liver cancer, has yet to be fully explored. Given the interdependence of various sleep behaviors, where changes in one sleep aspect often influence others, it is crucial to study the combined effects of these behaviors on liver-related outcomes [26]. Moreover, the potential interaction between genetic susceptibility and sleep patterns in the context of LRE remains under-explored.

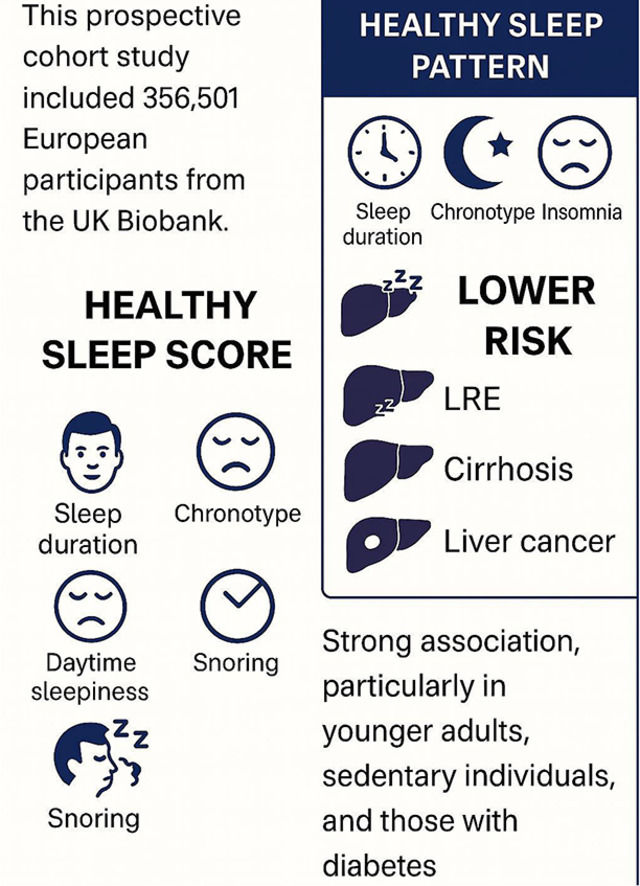

Therefore, this study aims to conduct a prospective investigation into the associations between healthy sleep patterns and liver-related events, utilizing data from the UK Biobank with a sample size of 356,501 participants. Additionally, we will examine the combined effects of sleep patterns and genetic susceptibility to LRE, exploring potential gene-environment interactions.

2Patients and methods2.1Study populationThe data for this study were sourced from the UK Biobank (approval number: 420,999), which enrolled over 500,000 participants between 2006 and 2010. Following informed consent, data on sleep patterns and other health-related variables were collected through questionnaires and physical measurements. The study was approved by the North West Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee.

2.2Assessment of sleep behaviorsSleep behaviors were assessed through questionnaires, covering sleep type, snoring, sleep duration, excessive daytime sleepiness, and insomnia. Participants’ sleep patterns were evaluated by asking whether they considered themselves to be: (1) an “absolute morning person”; (2) more of a “morning person” than an “evening person”; (3) more of an “evening person” than a “morning person”; or (4) an “absolute evening person.” Snoring was assessed by asking if a partner, close relative, or friend had ever complained about their snoring, with responses as: (1) Yes; (2) No. Sleep duration was gauged by asking about the total hours slept in a 24-hour period, including naps, with options: (1) < 7 h/day; (2) 7–8 h/day; (3) ≥ 9 h/day. Daytime sleepiness was assessed by asking how often participants felt the need to doze off during the day, with choices: (1) Rarely; (2) Occasionally; (3) Often; (4) Prefer not to answer. Insomnia was evaluated by asking whether participants had difficulty falling asleep or woke up in the middle of the night, with responses: (1) Rarely; (2) Occasionally; (3) Often; (4) Prefer not to answer.

2.3Assessment of healthy sleep score (HSS)The HSS was based on five key sleep factors: excessive daytime sleepiness, snoring, chronotype, insomnia, and sleep duration. Fan et al. [17]. code each sleep behavior of the subjects as to a low-risk group (1), and a high-risk group (0). The healthy sleep score is an aggregate of each of these five behaviors adding up to a potential range of 0 to 5. The greater the score, the more the subject is probable to be considered as a high-risk sleeper (HSP).

2.4Definition of liver-related events (LRE)Liver-related events (LRE) were defined using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes. Specifically, LRE encompassed the spectrum of chronic liver diseases coded as K71-K77, including non-alcoholic liver diseases, viral hepatitis, and other specified liver disorders. Cirrhosis was identified using ICD-10 codes K71.7, K72.1, K74.4, K74.5, K74.6, K76.6, I85.0, I85.9, I86.4, and I98.2, as well as OPCS4 codes J06.1, J06.2, T46.1, T46.2, G10.4, G10.8, G10.9, G14.4, G17.4, and G43.7. Liver cancer was diagnosed in accordance with ICD-10 code C22 including hepatocellular carcinoma (C22.0) however other liver malignancies were also included. Together, these conditions can be regarded as clinically important endpoints of the liver, such as the occurrence of cirrhosis and liver cancer, among other advanced liver complications.

2.5Assessment of covariatesCovariate data include sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, family history, and sleep behavior variables. Sociodemographic variables consist of age, gender, ethnicity, and the Townsend Deprivation Index (TDI). Lifestyle factors include smoking status (never/previously/current), alcohol consumption (never/previously/current), dietary habits (healthy/unhealthy), and sedentary behavior (more than 4 h/less than or equal to 4 h). Family history variables, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, low HDL cholesterol, and high triglycerides, were derived from self-reports of the participants regarding their family’s health history. Specifically, obesity status was collected by asking participants about the presence or absence of obesity in their immediate family. The sleep behavior variables include whether the participant sleeps 7 to 8 h daily (yes/no), follows an early sleeping pattern (yes/no), experiences frequent insomnia (yes/no), snores (yes/no), and frequently experiences daytime sleepiness (yes/no).

2.6Statistical analysisFor continuous variables, the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or the median (interquartile range, IQR) was used, and for categorical variables, the numbers (percentages) were utilized to summarize the baseline characteristics of the participants. To calculate the risk of liver cancer, cirrhosis and LRE associated with sleep among UK Biobank participants, we employed Cox proportional hazards models. The outcomes were expressed in the form of hazard ratios (HRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). Schoenfeld residuals were employed to assess the proportional hazards assumption, and no violations were found. Age, sex, and ethnicity adjustments were made to Model 1. Model 2 was further adjusted for sedentary hours, smoking status, education, Townsend deprivation index, drinking status and diet. In addition, Model 3 was adjusted for obesity, diabetes, hypertension, low HDL cholesterol and high triglycerides. In the final model, adjustments were also made for hepatic complications genetic risk score (HFC-GRS), cp1, cp2, cp3, cp4, and cp5.

Regarding the analysis of individual sleep factors, all five sleep parameters were simultaneously incorporated into the model. The connection between the continuous index score of a HSP and the risk of each event (such as liver cancer, cirrhosis, and LRE) was probed through restricted cubic spline analysis. Additionally, we further carried out analyses that were stratified according to age, sex, ethnicity, Townsend deprivation index (TDI), diet, smoking status, physical activity, drinking status, sedentary hours, and cardiometabolic risk factor. We also probed potential interactions by including a multiplicative interaction term between the HSS and the stratified variables in the model.

We also performed multiple sensitivity analyses to evaluate the reliability of our main findings. First, to avoid reverse causality, we excluded patients who developed, LREs (n = 1385), cirrhosis (n = 1379) and liver cancer (n = 1304) within the first two years of follow-up. Second, we created a weighted sleep score based on a composite score, calculated as follows: weighted sleep score = (β1 × sleep duration + β2 × chronotype preference + β3 × insomnia disorder + β4 × snoring + β5 × daytime sleepiness) × (5 / sum of the β coefficients), and examined the association of weighted HSS with the incidence of LRE, cirrhosis and liver cancer. β coefficients for each sleep factor were estimated using a Cox proportional hazards model that included all covariates from Model 4. Finally, considering that missing covariates might impact the results, we excluded patients with missing covariates (n = 57,533) and performed a complete-case analysis. All statistical analyses were carried out by means of R 4.3.3 software. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically difference.

2.7Ethical statementsWritten informed consent was obtained from each participant included in the study. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as reflected in a priori approval by the North-West Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (reference 11/NW/0382). Data for this study were sourced from the UK Biobank (approval number: 420,999), which has been approved by the aforementioned committee.

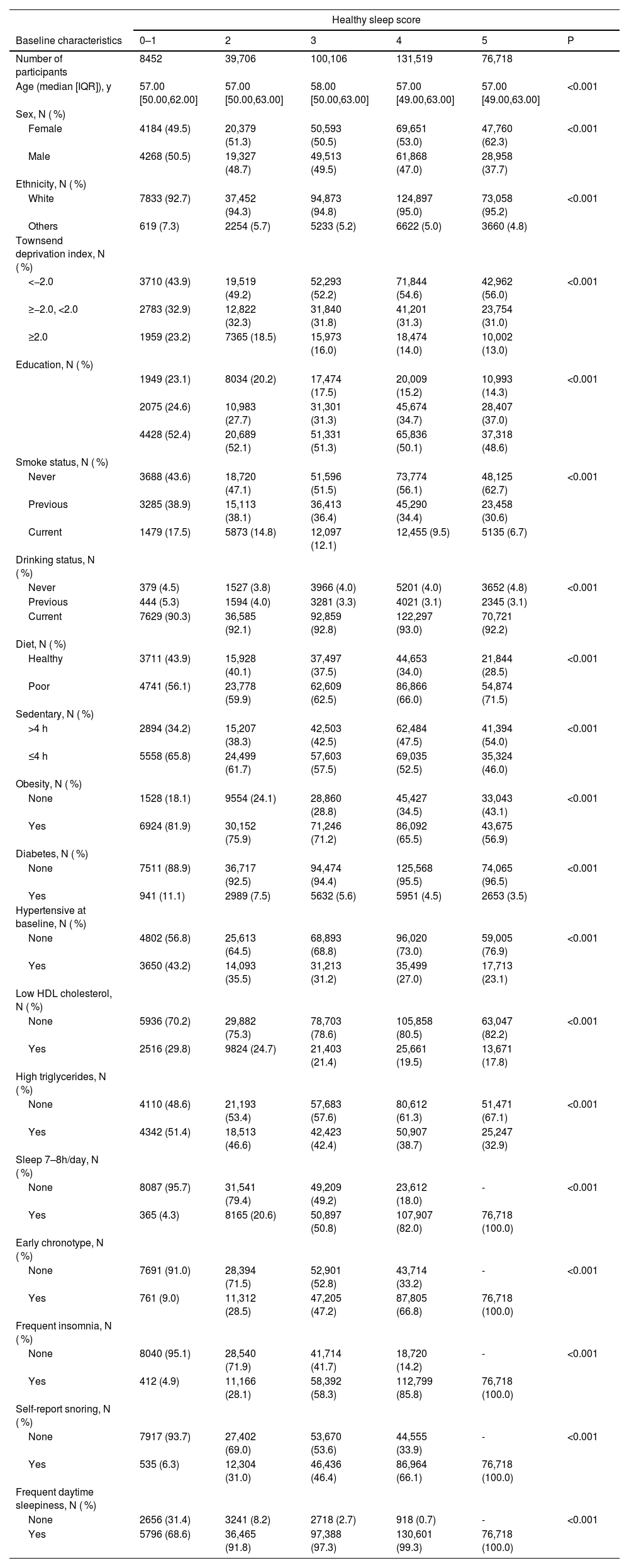

3ResultsA total of 356,501 subjects were enrolled in this research. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of subjects grouped by healthy sleep patterns. We found that 76,718 (20.13 %) participants were grouped to HSS of 5. Compared to HSS of 0–1, individuals adhering to HSS of 5 were more likely to be female, white ethnicity, lower TDI Score, non-smoker and those with long periods of sedentary time. The prevalence of metabolic comorbidities (obesity, diabetes, hypertension, low HDLC, and high triglycerides) was reduced in subjects with a HSS of 5.

Basic Characteristics of Participants Classified by Healthy Sleep Score.

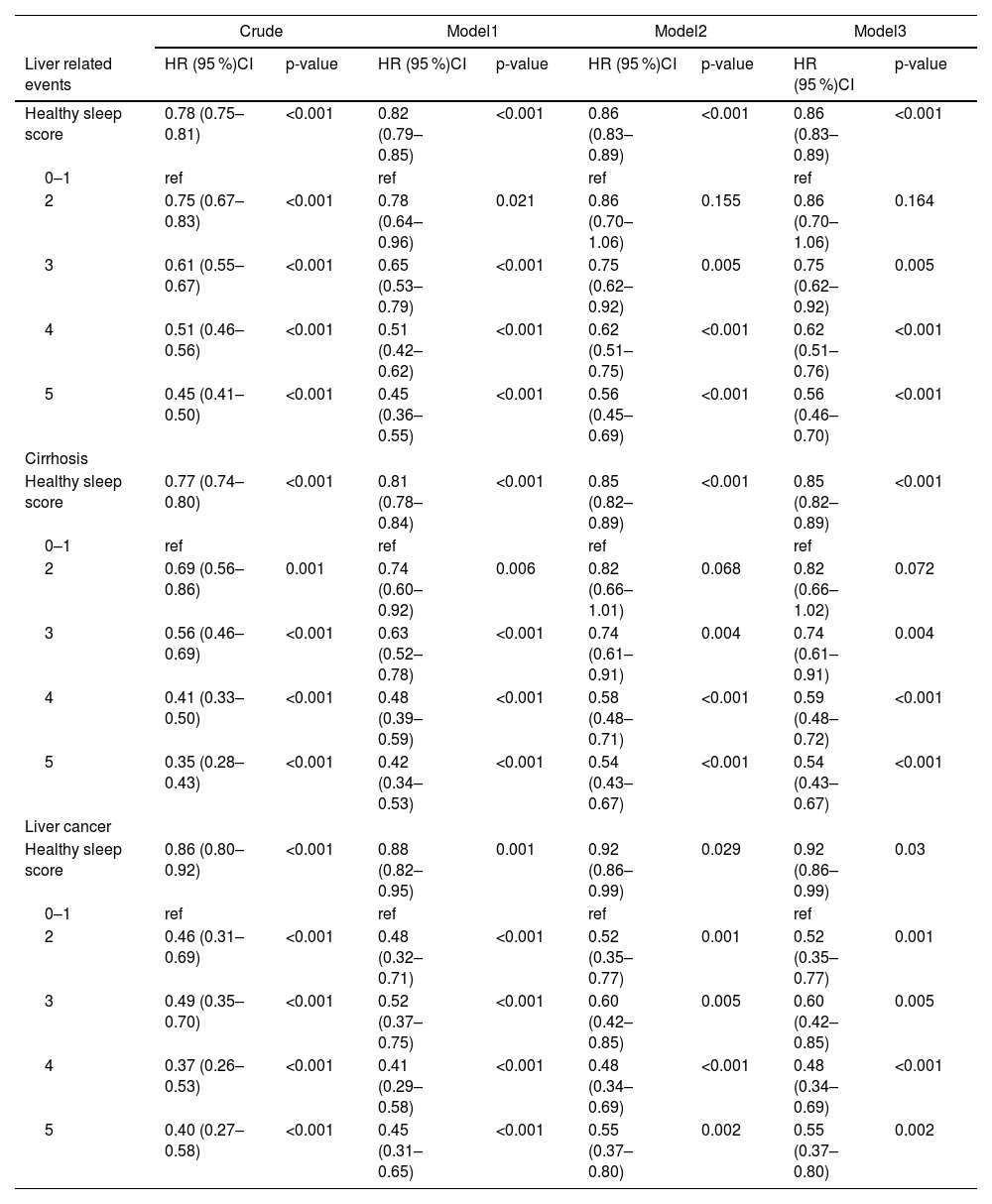

We documented 2441 incident LRE, 2197 incident cirrhosis, and 661 incident liver cancer over a median follow-up of 12.8 years. Table 2 summarized the association between HSP and incident LRE, cirrhosis and liver cancer. The HSS was generally inverse associated with risks of LRE, cirrhosis and liver cancer (p < 0.001). After adjusting for age, sex, ethnics, sedentary, smoking status, education, TDI, drinking status and diet, individuals with HSS of 5 had a 55 % reduced risk of LRE (HR=045; 95 % CI=0.36–0.55), a 58 % lower risk of cirrhosis (HR = 0.42; 95 % CI = 0.34–0.53), and a 55 % reduced risk of liver cancer (HR = 0.45; 95 % CI = 0.31–0.65) than individuals with HSS of 0–1 (Table 2, Model 1). The association between the HSS and incident LRE (HR = 0.56; 95 % CI = 0.45–0.69), cirrhosis (HR = 0.54; 95 % CI = 0.43–0.67), and liver cancer (HR = 0.55; 95 % CI = 0.37–0.80) remained in the multivariable model that further adjusted for metabolic comorbidities (obesity, diabetes, hypertension, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC), and high triglycerides) (Table 2, Model 2).

Association between healthy sleep score and incident Liver related events among 356,501 UK Biobank participants.

Model1: Age, Sex, Ethnics.

Model2: Model1+ Sedentary, Smoking status, Education, Townsend deprivation index, Drinking status, Diet.

Model3: Model2+ Obesity, Diabetes, Hypertension, Low HDLC, High triglycerides.

Model4: Model3+HFC-GRS, cp1, cp2, cp3, cp4, cp5.

HFC: hepatic complications; GRS: genetic risk score.

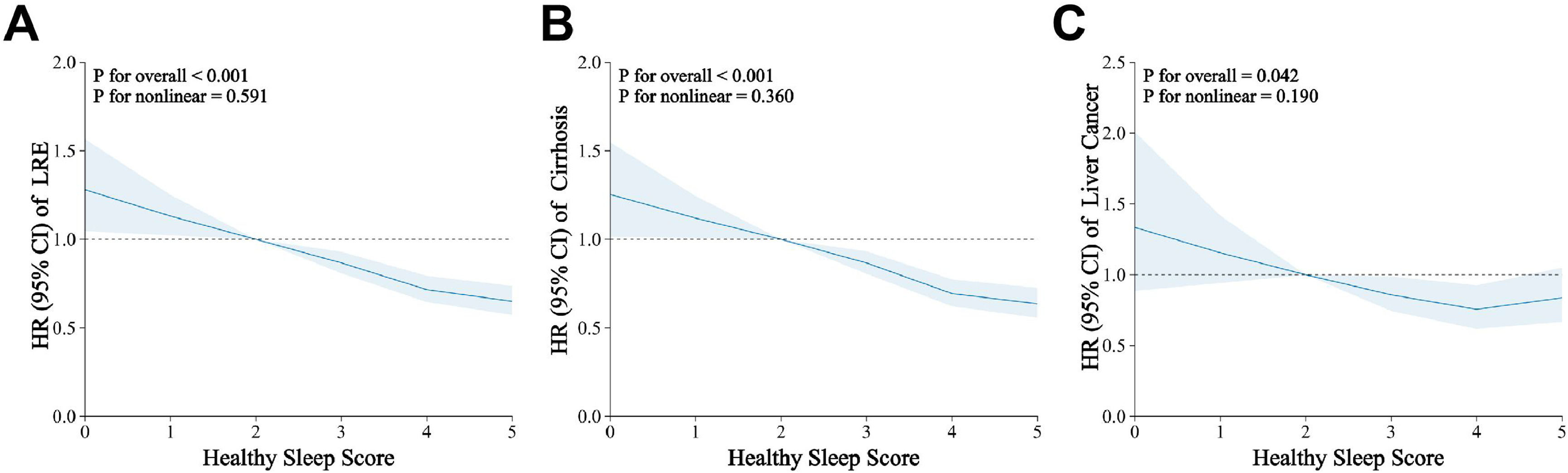

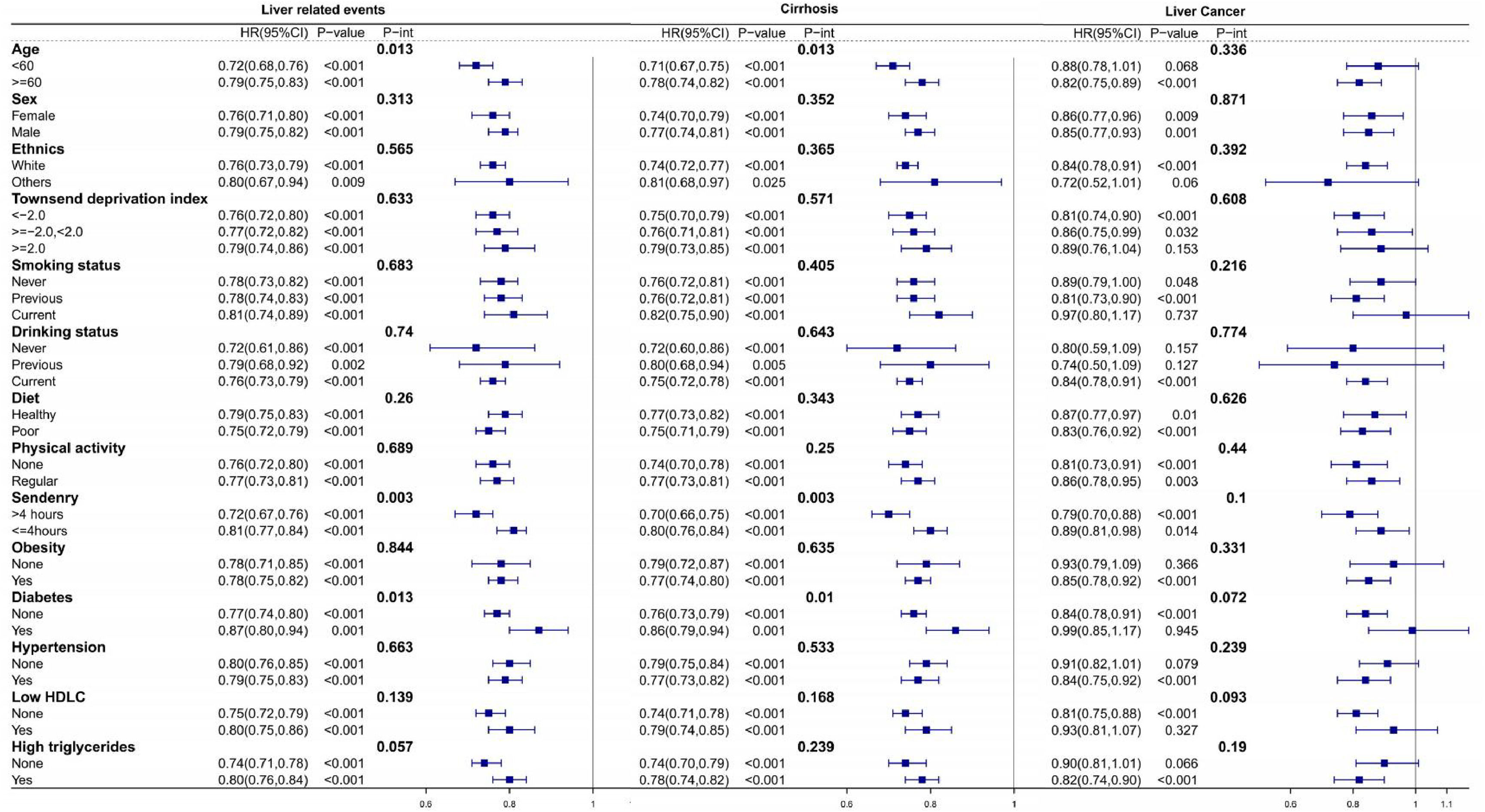

In the fully-adjusted model, the HSS of 5 was related to a 44 % decreased risk of LRE (HR = 0.56; 95 % CI = 0.46–0.70), a 46 % decreased risk of cirrhosis (HR = 0.54; 95 % CI = 0.43–0.67) and a 45 % decreased risk of liver cancer (HR = 0.55; 95 % CI = 0.37–0.80) compared to HSS of 0–1 (Table 2, Model 3). A linear relationship between the HSS and LRE (Fig. 1A, P for Nonlinear=0.591), cirrhosis (Fig. 1B, P for Nonlinear=0.360) and liver cancer (Fig. 1C, P for Nonlinear=0.190) is shown by restricted cubic spline regression in the dose-response studies. Specifically, each unit increase in the HSS was related to a 14 % contraction in the risk of developing LRE (HR = 0.86; 95 % CI = 0.83–0.89), a 15 % decrease in the risk of developing cirrhosis (HR = 0.85; 95 % CI = 0.82–0.89) and an 8 % reduction in the risk of liver cancer (HR = 0.92; 95 % CI = 0.86–0.99) (Table 2, Model 3). We found that the age (<60 or ≥60), sedentary (>4 h or ≤4 h), and diabetes (none or yes) significantly modified the associations of the HSP with the risk of LRE and cirrhosis (P-int< 0.05). The inverse relationship between the HSS and the likelihood of LRE and cirrhosis appeared to be stronger among subjects who were younger, having more sedentary time and having diabetes at baseline. All subgroups showed a generally similar association between the risk of the HSS and risk of liver cancer (P-int > 0.05) (Fig. 2). Sensitivity analyses that removed cases of incident that occurred within the first two years of follow-up produced results comparable to the main study (Supplementary Table 1). Similar results were obtained when examining the association between a weighted sleep score and cirrhosis, liver cancer, and LRE (Supplementary Table 2). The results did not change when populations with missing covariate data were excluded and the completed-case data was analyzed (Supplementary Table 3).

Dose-response relationship between healthy sleep score and Liver related events. Models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnics, sedentary, smoking status, education, Townsend deprivation index, drinking status, diet, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, low HDLC, high triglycerides, HFC-GRS, cp1, cp2, cp3, cp4, cp5.

Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios for Liver related events in subgroups. Stratified analysis was performed according to subgroups of each covariate. Models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnics, physical activity, sedentary, smoking status, education, Townsend deprivation index, drinking status, diet, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, low HDLC, high triglycerides, HFC-GRS, cp1, cp2, cp3, cp4, cp5.

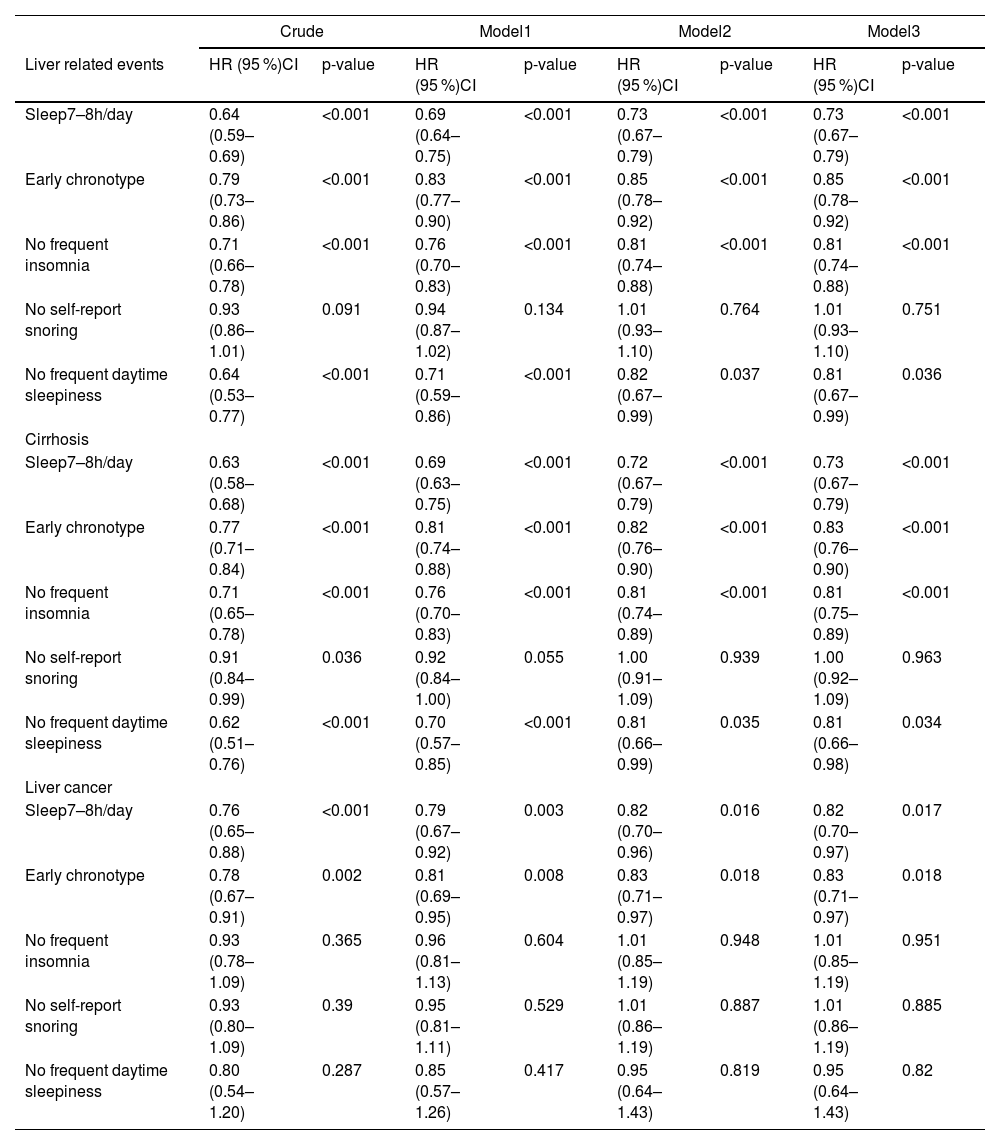

We also investigated the associations between the risk of liver cancer, cirrhosis, and LRE and other components of good sleep parameters. A 27 %, 15 %, 19 % and 19 % lower risk of LRE and a 27 %, 17 %, 19 % and 19 % lower risk of cirrhosis, respectively, were independently linked to sleep 7–8 h per day, early chronotype, no frequent insomnia, and no frequent daytime sleepiness in the multivariable adjusted model (P < 0.05). Sleep 7–8h/day and early chronotype was each independently associated with a 18 % and 17 % reduced risk of liver cancer, respectively (P < 0.05) (Table 3, Model 3).

Hazard ratios of Liver related events by individual healthy sleep factors among 356,501 UK Biobank participants.

Each individual component was modeled as binary variable: meeting or not meeting the healthy criterion.

Model1: Age, Sex, Ethnics.

Model2: Model1+ Sedentary, Smoking status, Education, Townsend deprivation index, Drinking status, Diet.

Model3: Model2+ Obesity, Diabetes, Hypertension, Low HDLC, High triglycerides.

Model4: Model3+HFC-GRS, cp1, cp2, cp3, cp4, cp5.

HFC: hepatic complications; GRS: genetic risk score.

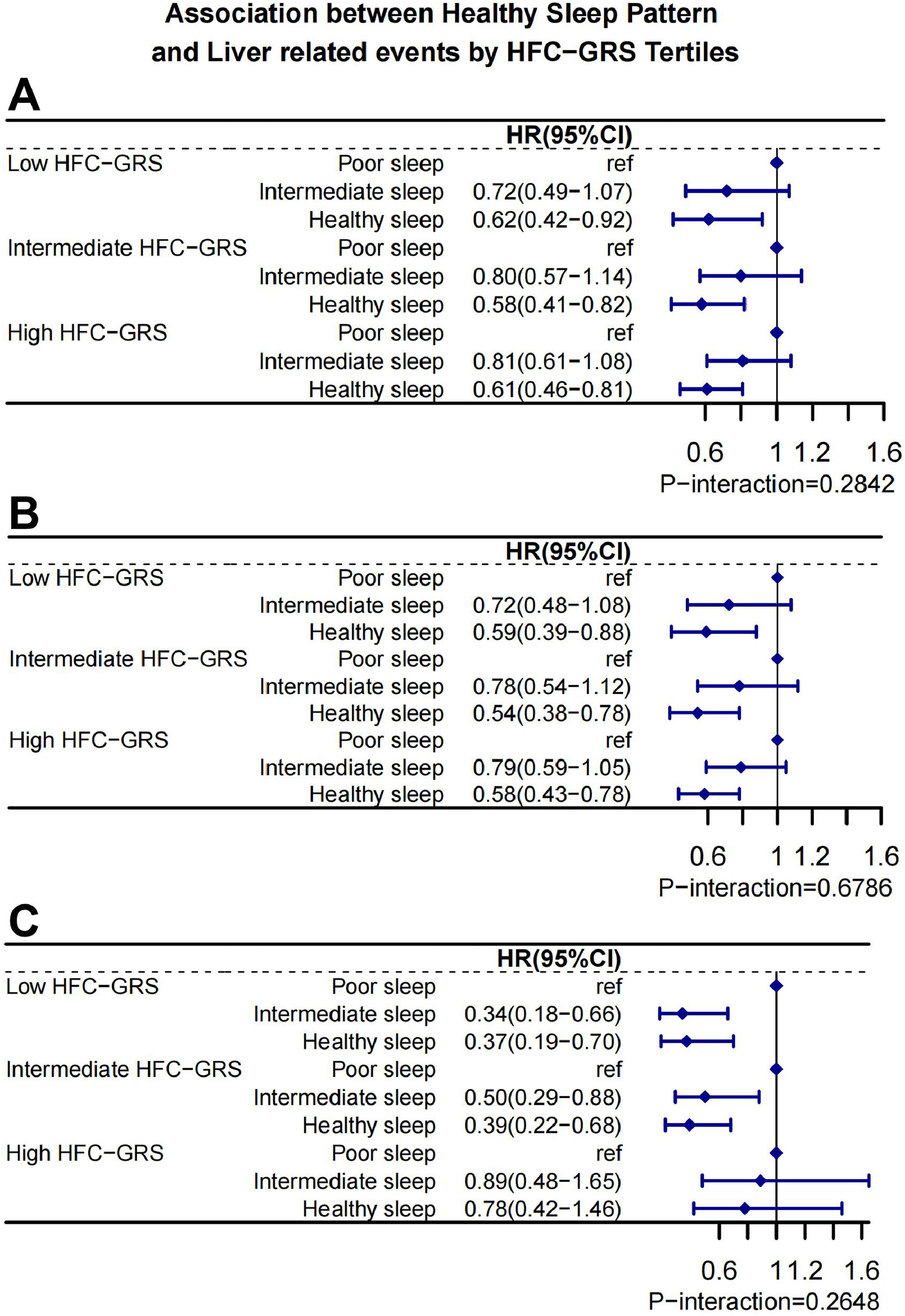

We further assessed whether the association between the HSP and LRE, cirrhosis as well as liver cancer was modulated by the HFC-GRS. Healthy sleep patterns and HFC-GRS did not interact statistically significantly, according to our findings (P-int>0.05). Subjects with sleep pattern of healthy had generally the lower risk of LRE, cirrhosis and liver cancer in different HFC-GRS (Fig. 3).

Healthy sleep pattern and risks of Liver related events. Stratified analysis according to the tertile categories of HFC-GRS. Models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnics, sedentary, smoking status, education, Townsend deprivation index, drinking status, diet, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, low HDLC, high triglycerides, HFC-GRS, cp1, cp2, cp3, cp4, cp.

In this prospective cohort study of 356,501 UK Biobank participants, we examined the relationship between a newly developed Healthy Sleep Score (HSS)—which integrates factors such as the absence of insomnia, being a morning type, no excessive daytime sleepiness, sleeping 7 to 8 h nightly, and no frequent snoring—and the incidence of liver-related events (LRE), cirrhosis, and liver cancer. Our findings suggest that a higher HSS is associated with a significantly reduced risk of incident LRE, cirrhosis, and liver cancer. Specifically, an HSS of 5 was linked to a 44 %, 46 %, and 45 % reduction in the risk of LRE, cirrhosis, and liver cancer, respectively, compared to an HSS of 0–1. These results highlight the protective effects of adhering to a healthy sleep pattern (HSP), particularly as the global prevalence and mortality associated with LRE continue to rise. Promoting modifiable lifestyle factors, such as maintaining a healthy sleep pattern, could serve as an important preventive strategy for these diseases.

4.1Comparison with other studiesOur findings are in line with previous studies that have explored the relationship between liver cancer, cirrhosis, MASLD, and various lifestyle factors, including sleep. These studies have consistently shown that sleep plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of liver diseases. For example, sleep duration has been negatively correlated with MASLD in males [31], and sleep duration has independently impacted metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in females [12]. Additionally, Fares et al. [32]. reported a strong association between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), excessive daytime sleepiness, and liver cirrhosis. A cohort study of 10,541 American adults found a link between insomnia and MASLD [33]. However, most existing research has focused on individual sleep behaviors and their relationship with liver diseases, with little attention given to the impact of a comprehensive sleep pattern on liver health. Our study is, to our knowledge, the first to evaluate the association between a holistic healthy sleep pattern—characterized by an early chronotype, adequate sleep duration, absence of insomnia, no snoring, and no excessive daytime sleepiness—and liver-related events, liver cancer, and cirrhosis. These findings underscore the significance of HSP in reducing the risk of liver disease, offering new insights for the management of liver-related conditions.

4.2Strength of evidence and consistency with previous researchThe observed relationship between HSS and liver disease risk is consistent with several recent studies that have demonstrated a significant association between poor sleep patterns and the development of liver disease. For instance, individuals with a low HSS (0–1) were found to have a significantly higher risk of liver cancer compared to those with a higher HSS (HR: 1.46 [1.15–1.85]) [34]. Our study corroborates these findings by demonstrating that for each unit increase in HSS, the risk of LRE decreased by 14 %, cirrhosis risk dropped by 15 %, and liver cancer risk was reduced by 8 %. Notably, we observed that prolonged sedentary behavior (more than 4 h) and diabetes further enhanced the association between HSP and a lower risk of LRE and cirrhosis. These results emphasize the importance of managing sleep habits, particularly in high-risk populations such as younger, sedentary individuals and those with diabetes.

Additionally, our study highlights the critical role of an early chronotype and sleeping 7 to 8 h daily as independent factors that contribute to a lower risk of liver-related events, cirrhosis, and liver cancer. These findings align with existing literature that has demonstrated both short and long sleep durations, insomnia, snoring, excessive daytime sleepiness, and late chronotype as contributors to increased liver disease risk [35–37]. Despite the interconnectedness of these individual sleep behaviors, no prior studies have explored their combined influence as part of an overall healthy sleep pattern. Given the complexity of sleep behaviors and their potential impact on liver health, our novel healthy sleep score offers a valuable tool for assessing the development of liver disease.

Converging evidence indicates that sleep disturbances are closely linked to greater histologic severity of liver disease. In MASLD specifically, poor sleep quality has been associated with advanced fibrosis—the principal prognostic determinant—independent of traditional metabolic comorbidities [38]. Our findings align with this gradient of risk: individuals adhering to the healthiest composite sleep pattern exhibited substantially lower risks of cirrhosis and other liver-related events, implying that adverse sleep phenotypes track with progression toward more advanced liver pathology. Biologically, circadian misalignment and sleep-disordered breathing can intensify insulin resistance, sympathetic activation, systemic inflammation, and intermittent hypoxia, collectively promoting hepatocellular injury and hepatic stellate cell activation—plausible pathways to fibrosis. These data support integrating routine sleep assessment (including screening for insomnia symptoms and obstructive sleep apnea) into MASLD risk stratification and prioritizing noninvasive fibrosis evaluation in patients with poor sleep. Rigorous intervention studies are now warranted to test whether improving sleep quality can attenuate fibrosis progression and, ultimately, reduce downstream liver-related events.

4.3Lack of interaction with hepatic genetic riskInterestingly, our study did not find a statistically significant interaction between healthy sleep patterns (HSP) and the hepatic function-related genetic risk score (HFC-GRS). Although genetic factors such as HFC-GRS have been linked to liver disease susceptibility [48], our results suggest that the impact of a healthy sleep pattern on liver-related events, cirrhosis, and liver cancer risk operates independently of genetic predisposition. This finding is important because it implies that, regardless of genetic risk, individuals who maintain a healthy sleep pattern may experience a reduced risk of developing liver diseases. These results align with the broader understanding that lifestyle modifications—especially improved sleep hygiene—can have significant protective effects, irrespective of genetic background.

The absence of the significant interaction between sleep behaviors and genetic risk could be attributed to the multiplicity of the biological pathways in which sleep impacts upon the liver health, and which are not simply impacted by the genetic risk as determined by the HFC-GRS. Future studies should endeavor to establish a biological basis underlying this association and how behaviors associated with sleep may play a role interacting with genes and metabolic phenomena to have bearing on the progression of liver diseases.

4.4Potential mechanismsWhile the precise mechanisms linking sleep behaviors with liver-related events (LRE) remain unclear, several potential pathways may explain the observed association. Disruptions in circadian rhythm, for instance, can lead to altered melatonin metabolism and abnormal liver enzyme activity, particularly affecting cytochrome P450, a key enzyme involved in liver function [39]. Disturbed circadian rhythms and high melatonin level have also been proposed to be a contributive factor to hepatoma development [40,41]. Furthermore, the links that have been drawn between sleep disorders and liver diseases are heightened sympathetic nervous system activity, stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and the induction of high levels of oxidative stress all of which may contribute to the development of metabolic liver diseases or liver damage [42,43]. Additionally, snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness can be signs of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which is a risk factor to the occurrence and development of liver-related diseases [44,45]. Future research should explore these mechanisms further to clarify the biological pathways through which sleep patterns may influence liver health.

4.5Public health implicationsOur findings underscore the public health importance of adhering to a healthy sleep pattern as a preventive strategy for liver-related events (LRE), cirrhosis, and liver cancer. The protective effect of healthy sleep habits is especially pronounced among younger individuals, those with more sedentary behaviors, and individuals with diabetes. Given the growing global burden of liver diseases, these results suggest that promoting healthy sleep practices—particularly among high-risk groups—could significantly reduce the incidence of liver diseases and associated healthcare costs. This approach offers a scalable and cost-effective public health intervention that could complement existing preventive measures for liver-related conditions, contributing to improved health outcomes worldwide.

4.6Limitations and future directionsWhile the large sample size and prospective design are strengths of our study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the Healthy Sleep Score was assessed only at baseline, and long-term follow-up sleep data were not available. Future studies should incorporate repeated measurements over time to examine the long-term impact of sleep behaviors on liver health. Additionally, the Healthy Sleep Score was based on self-reported data, which may introduce measurement biases. Third, as a prospective observational study, our findings do not establish causal relationships. Future research should focus on experimental designs, such as randomized controlled trials, to validate these associations. Finally, the study participants were predominantly from the UK, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations. Including diverse cohorts from different regions and ethnic groups would help enhance the external validity of our results.

5ConclusionsOverall, our study demonstrates that adherence to a healthy sleep pattern is significantly associated with a reduced risk of liver-related events (LRE), cirrhosis, and liver cancer. These findings emphasize the importance of maintaining a healthy sleep pattern as a preventive strategy for liver disease, particularly in younger, sedentary individuals and those with diabetes. By improving public health outcomes, this approach could play a pivotal role in reducing the global burden of liver diseases.

Author contributionsAll authors contributed to the conception and design; the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; drafted or critically revised the manuscript; approved the final version; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The corresponding authors, Ailan Chen and Hongliang Xue, served as guarantors of the work’s integrity and accept full responsibility for the study and the decision to submit.

FundingThis work was partly funded by Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease (SKLRD-OP-202510).

Uncited referencesNone.