Bacterial infections are common and serious complications in patients with cirrhosis, affecting up to 50 % of those hospitalized and contributing to in-hospital mortality rates of up to 25 % [1,2]. While spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is the most common infection, urinary tract infections (UTIs) typically rank second, especially in the Americas and Europe, and together they account for up to 60 % of all infections [3,4].

UTIs can be challenging to diagnose in patients with cirrhosis, as typical symptoms may be absent or nonspecific. Diagnosis depends on urine cultures, which take 24 to 48 h and may not clearly distinguish actual infection from asymptomatic bacteriuria. This diagnostic uncertainty, along with their high frequency, often results in inappropriate antibiotic use [5].

Cirrhosis-related UTIs often involve multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) [1,2], complicating empiric treatment and potentially worsening sepsis outcomes [6]. The growing and regionally variable prevalence of MDRO makes it challenging to meet the recommended 80–90 % coverage targets [7].

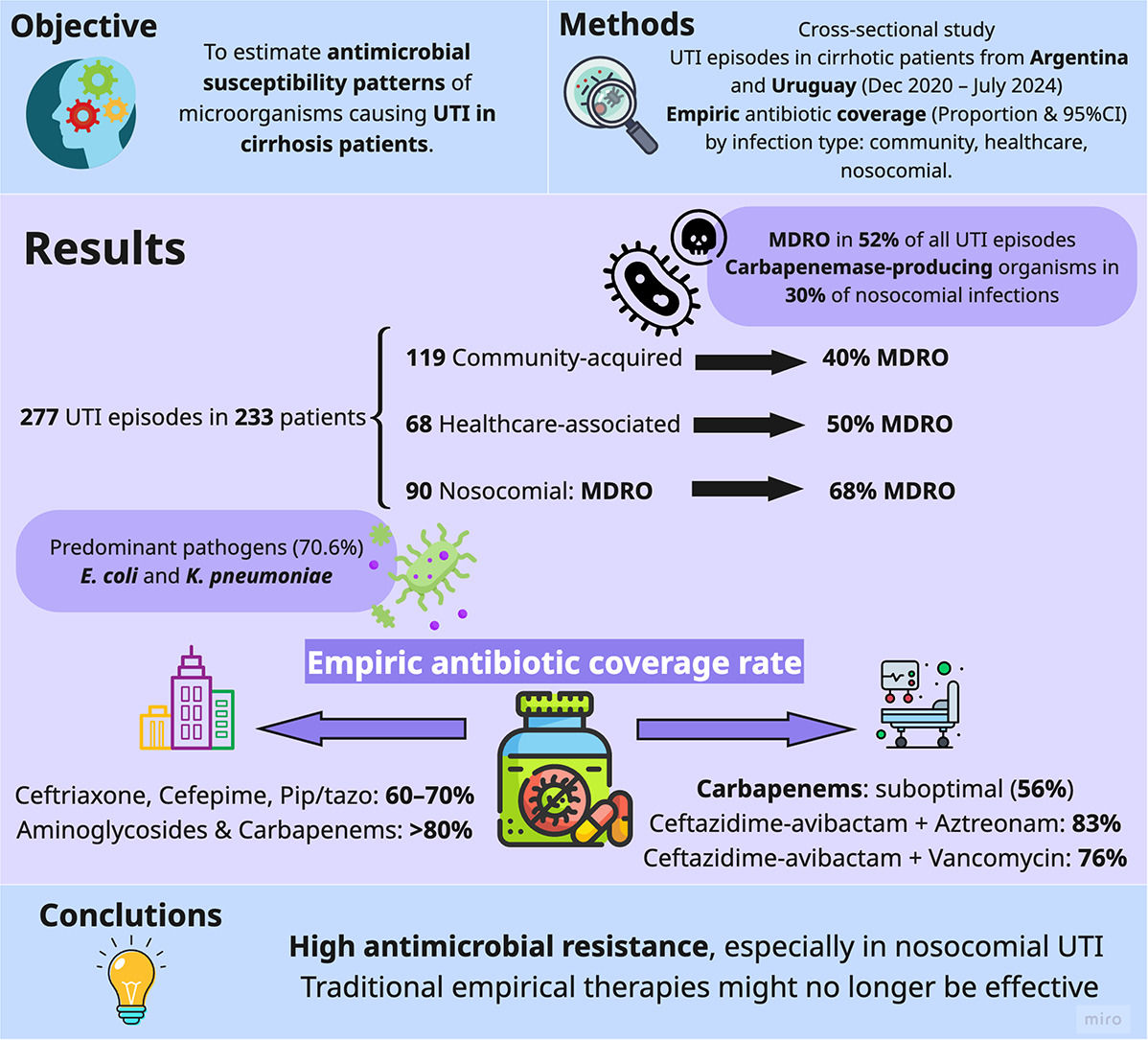

This study aimed to evaluate the antimicrobial susceptibility of pathogens causing UTIs in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis.

2Patients and MethodsThis cross-sectional study analyzed data from a prospective multicenter registry of bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT0634940), established in Argentina and Uruguay in December 2020 [8]. The registry includes consecutive episodes of culture-positive infections in hospitalized cirrhotic patients aged ≥17, excluding those with prior transplants or without informed consent. For the present analysis, a subset of episodes was selected and classified as UTIs, aiming to evaluate the antimicrobial susceptibility of the causative pathogens. UTIs were defined as the presence of symptoms (e.g., fever ≥38 °C, dysuria, urgency, frequency, or suprapubic tenderness) in addition to a positive urine culture (≥10 ³ CFU/mL of bacterial growth). As of July 2024, the registry included 689 infection episodes, of which 277 were UTIs. The unit of analysis was the UTI episode, permitting multiple entries per patient. The registry adhered to a standardized protocol based on the WHO’s Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System [9]. The supplementary material provides further methodological details, including information regarding data collection procedures, an extended description of the microbiological methods, and a detailed account of the statistical analysis performed.

2.1Ethical statementAll patients provided informed consent, directly or through a legal representative. The study received approval from the IRBs at all participating centers (#5821) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

3ResultsFrom December 2020 to July 2024, a total of 277 UTI episodes were recorded in 233 patients with cirrhosis across 19 centers in Argentina and Uruguay. These episodes yielded 286 bacterial isolates, as some infections involved more than one organism. Supplementary Table S1 provides details about the participating centers, and Table 1 summarizes the key clinical characteristics.

Patient characteristics registered at each episode of urinary tract infection (n = 277).

| Characteristics | n = 277 |

|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 153 (55.2 %) |

| Cirrhosis etiology, n (%) | |

| Alcohol-related | 94 (33.9 %) |

| Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease | 83 (30.0 %) |

| Viral | 27 (9.7 %) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 26 (9.4 %) |

| Primary biliary cholangitis | 21 (7.6 %) |

| Cryptogenic | 13 (4.7 %) |

| Other | 14 (5.1 %) |

| Prior medications, n (%) | |

| Norfloxacin prophylaxis | 41 (14.8 %) |

| Ciprofloxacin prophylaxis | 3 (1.1 %) |

| Rifaximin | 129 (46.6 %) |

| Other antibiotics* | 17 (6.1 %) |

| Beta-blockers | 129 (46.6 %) |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 169 (61.0 %) |

| Recent infections and/or recent antimicrobial treatments (last 3 months), n (%) | |

| Use of therapeutic antibiotics for ≥ 5 consecutive days # | 140 (50.5 %) |

| Hospital admission within the last year for bacterial infection | 199 (71.8 %) |

| Cirrhosis/Liver disease severity scores, median (IQR) | |

| Child Pugh score | 10 (8–12) |

| MELD Na score | 20 (14–25) |

| Listed for liver transplantation, n (%) | 92 (33.2 %) |

The unit of analysis for this table is the episode of urinary tract infection (N = 277), which involved 233 patients. Abbreviations: MELD Na: Model for End-stage Liver Disease Sodium, IQR: Interquartile Range.

More than two-thirds of UTI episodes (68.6 %, n = 190) occurred while patients were on some form of antibiotic prophylaxis, primarily rifaximin (46.6 %, n = 129), with norfloxacin being less common (14.8 %, n = 41). Nearly half of these episodes (50.5 %, n = 140) occurred after patients had received at least five consecutive days of therapeutic antibiotics for another bacterial infection within the past three months. Additionally, 71.8 % of UTI episodes occurred in patients with hospital admissions due to bacterial infections within the previous year. Regarding the location where the infection was acquired, 119 UTI episodes were community-acquired (43.0 %), 68 were health-associated (24.5 %), and 90 were nosocomial (32.5 %).

Most UTI episodes were monomicrobial (96.8 %, n = 268), with only a small proportion involving two organisms (3.2 %, n = 9), resulting in 286 bacterial isolates. Gram-negative organisms predominated (n = 235, 82.2 %), with Escherichia coli accounting for 41.9 % (n = 120) and Klebsiella pneumoniae for 26.9 % (n = 77) of the isolates overall. Enterococcus was the third most frequent bacterium, comprising 14.0 % (n = 40) of the isolates. When evaluating the distribution of microorganisms based on where the infection was acquired, E. coli was the most common isolate in both community-acquired (59.2 %) and health-associated infections (41.2 %), while Klebsiella pneumoniae was the most prevalent in nosocomial infections (38.7 %). Enterococcus primarily represented the gram-positive organisms, with a higher prevalence in health-associated infections (25.0 %) compared to community-acquired (9.2 %) and nosocomial infections (12.9 %). Supplementary Table S2 provides further details regarding bacterial isolates.

MDRO was observed in 143 of the 277 UTI episodes (51.6 %, 95 % CI: 45.7–57.5), with prevalence increasing from 40.3 % (95 % CI: 31.8–49.5) in community-acquired infections to 50.0 % (95 % CI: 38.0–62.0) in healthcare-associated infections, and 67.8 % (95 % CI: 57.2–76.8) in nosocomial cases. Extensive drug-resistant isolates were reported in 11.6 % (95 % CI: 8.3–15.9) of the episodes, and pan-drug-resistant phenotypes were present in 2.2 % (95 % CI: 1.0–4.7). In a temporal analysis, MDRO significantly increased from 2021 (42.6 %, 95 % CI: 30.0–56.2) to 2023 (61.1 %, 95 % CI: 51.5–69.9) (Fig. 1). During this period, the proportion of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing organisms remained stable, while carbapenemase-producing organisms increased (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2).

Multidrug-resistant organisms proportion over time.

Footnote: The graph illustrates the proportion of urinary tract infection episodes with at least one Multidrug-resistant organism from 2021 to 2023: 2021 (42.6 %, 95 %CI: 30.0–56.2), 2022 (48.7 %, 95 %CI: 37.6–59.9), 2023 (61.1 %, 95 %CI: 51.5–69.9). The number of UTI episodes enrolled each year is as follows: 2021 = 54, 2022 = 76, 2023 = 108. Since 2020 had few episodes (n = 7) and 2024 is still in progress, they have been intentionally excluded from this graphic.

When considering the total number of isolated bacteria (n = 286), 147 (51.4 %) MDRO were identified. Table 2 displays the key mechanisms of MDRO. The most frequent resistance mechanism was the production of extended-spectrum β-lactamase by Enterobacteriaceae (56.5 %), followed by carbapenemase-producing organisms (28.6 %) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (9.5 %). As shown in Table 2, the multidrug resistance patterns varied based on where the infection was acquired.

Key mechanisms of multidrug-resistance identified in multidrug-resistant organisms. Estimates are presented for the entire study population and by the place where the infection was acquired (n = 147).

KPC: Klebsiella pneumoniae producing carbapenemase; Oxa: Oxacillinase; MBL: Metallo-β-lactamase. The unit of analysis of this table is Multidrug resistant Organism. The calculation for the proportions of each resistance mechanism uses a total of 147 multidrug-resistant bacteria as the denominator (for the global estimates) or the respective denominators considering the absolute number of multidrug-resistant isolates of each type of infection (community-acquired, healthcare-associated, and nosocomial). No methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa with difficult-to-treat resistance or multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter were found.

The proportion of carbapenemase-producing organisms among Enterobacteriaceae varied based on the type of infection. In nosocomial infections, carbapenemase-producing bacteria represented 35.5 % (95 % CI: 25.5–47.0) of Enterobacteriaceae isolates, which was higher than in healthcare-associated infections at 7.7 % (95 % CI: 2.9–19.0) and community-acquired infections at 8.8 % (95 % CI: 4.6–16.2). The prevalence of carbapenemase-producing bacteria was even more pronounced when specifically focusing on Klebsiella species. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella accounted for 55.3 % (95 % CI: 39.0–70.4) of the isolates in nosocomial infections, while representing 23.5 % (95 % CI: 8.7–49.0) and 30.8 % (95 % CI: 15.8–51.3) in healthcare-associated and community-acquired infections, respectively.

Table 3 presents the antibiotic susceptibility of UTI episodes. For community-acquired UTI episodes (n = 119), commonly used antibiotics such as ceftriaxone, cefepime, and piperacillin-tazobactam achieved 60–70 % coverage rates. Aminoglycosides and ertapenem provided approximately 80 % coverage, while imipenem or meropenem reached 90 %. Combining these with vancomycin or linezolid offered additional coverage.

Proportions of UTI episodes susceptibility to frequently used antibiotics, stratified by the place where the infection was acquired (n = 278).

The unit of analysis for this table is the episode of urinary tract infection. When an UTI episode has two isolated bacteria, sensitivity is calculated for a single antibiotic or combination that covers both isolations. # Nitrofurantoin was tested in 91 community-acquired cases, 47 health-associated cases, and 65 nosocomial infections. Nitrofurantoin achieves good concentrations in urine but does not concentrate well in plasma.

In health-associated UTI episodes (n = 68), aminoglycosides alone (70.1 %, 95 % CI: 57.9–80.1), imipenem or meropenem alone (76.5 %, 95 % CI: 64.7–85.2), or in combination with vancomycin (82.4 %, 95 % CI: 71.1–89.8) were alternatives that covered approximately 80 % of episodes. If the clinical scenario requires higher coverage, options include the combination of imipenem or meropenem with linezolid (89.7 %, 95 % CI: 79.6–95.1) or ceftazidime-avibactam plus vancomycin (88.2 %, 95 % CI: 77.9–94.1).

In cases of nosocomial UTI episodes (n = 90), the options available for adequate coverage were limited. Commonly recommended antibiotics for nosocomial UTI, such as the combination of a carbapenem and a glycopeptide, achieved coverage rates of <70 %. In contrast, more effective options included ceftazidime-avibactam combined with aztreonam, which provided 83.0 % coverage (95 % CI: 73.4–89.6), and ceftazidime-avibactam combined with vancomycin, which offered 76.1 % coverage (95 % CI: 61.1–80.2). Overall, the explored antimicrobial regimens did not yield higher coverage rates for nosocomial UTI.

4DiscussionIn this study, we observed high rates of antimicrobial resistance among UTI isolates, particularly in nosocomial settings. Multidrug resistance rates approached 70 % in nosocomial UTIs, with one-third of the isolates demonstrating resistance to carbapenems. These findings challenge the adequacy of current empiric treatment strategies recommended by available clinical guidelines [10,11], raising concerns about their ongoing effectiveness. In addition, reconciling therapeutic recommendations is further complicated by the lack of consistency in how clinical scenarios are defined across these guidelines. Beyond the distinction between community-acquired and nosocomial infections, scenarios such as uncomplicated versus complicated UTIs, sepsis, and others are used variably, sometimes without standardized criteria.

Guidelines recommend fosfomycin or nitrofurantoin for patients with nosocomial uncomplicated UTIs, while carbapenem and a glycopeptide are suggested for critically ill individuals [10,11]. However, caution is warranted with nitrofurantoin. Although it provides excellent coverage for community-acquired and healthcare-associated UTIs, its effectiveness in nosocomial infections is more limited. Moreover, nitrofurantoin does not concentrate adequately in the kidneys or bloodstream, making it suitable only for cystitis [12]. A similar caution applies to fosfomycin, as it is ineffective in treating bacteremia [13]. Regarding the recommended use of carbapenem-glycopeptide combinations, such as carbapenem plus vancomycin [10,11], this strategy may still provide insufficient coverage. Alternatives targeting highly resistant Enterobacteriaceae, such as ceftazidime-avibactam (alone or combined with aztreonam), may improve coverage against these pathogens. However, the growing incidence of Enterococcus infections in healthcare-associated and nosocomial settings raises additional concerns. This suggests that broad-spectrum regimens directed primarily at resistant gram-negative bacilli may be inadequate as monotherapy, and that agents targeting gram-positive cocci—such as vancomycin or linezolid—may be required to ensure adequate coverage in these UTIs.

As a final note, the growing burden of multidrug resistance should be considered within the broader global context, particularly in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have impacted resistance patterns through changes in antimicrobial use and healthcare practices[14].

5ConclusionsAntimicrobial resistance has reached a critical point, especially in high-risk groups like hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Our findings reveal key challenges for empiric treatment and suggest that emerging evidence could support more targeted therapeutic strategies. Continued surveillance and coordinated efforts are essential to adapt to shifting resistance trends.

Author contributionsStudy concept: CV, SM, AG, GGP; Study design: CV, SM, AG, GGP; Enrolment of patients and data collection: CV, GGP, EGB, IPI, CMB, ADS, MDM, AP, LT, JP, JB, BOS, MM, MA, GG, AR, AZ, PC, ME, MLG, MC, SS, JT, NV, DA, MD, FC, AG, SM; Analysis and interpretation of data: CV, SM, GGP; Drafting of the manuscript: CV, SM, GGP; Critical revision for important intellectual content: CV, GGP, EGB, IPI, CMB, ADS, MDM, AP, LT, JP, JB, BOS, MM, MA, DG, GG, AR, AZ, PC, ME, MLG, MC, SS, JT, NV, DA, MD, FC, AG, SM.

FundingThe John C. Martin Foundation and Sociedad Argentina de Hepatologia.

None.

We thank all the researchers and collaborators of the prospective bacterial infections registry in Latin America: Rojas, German Francisco; Navarro, Lucia; Perez, Maria Daniela; Agozino, Marina; Gutierrez Acevedo, Maria Nelly; Valverde, Marcelo; Díaz Ferrer, Javier; Garavito-Rentería, Jorge Luis; Zambrano Huailla, Rommel Eiger; Díaz Ferrer, Javier; Tenorio Castillo, Laura; Montes Teves, Pedro Andrés; Yance Contreras, Stalin; Aquino Vargas, Karla Melissa; Veramendi Shult, Esther Genoveva Isabel; Cabrera Cabrejos, Maria Cecilia; Rodriguez, Kriss del Rocio; Marcelo, Santiago; Garcia Encinas, Carlos; Carrera Estupiñan, Enrique; Becerra, Vanessa Alejandra; Duran Muñoz, Geraldine Adriana; Mattos, Angelo; Roppa Maboni, Laura; Alves de Paiva, Adenylza Flavia; Poveda Salinas, Yohana; Velarde Ruiz Velasco, José Antonio; García Jiménez, Edgar Santino; Bessone, Fernando; Stieben, Teodoro. We are also thankful to Fundación Icalma for its support.